Victoria Sadler's Blog, page 24

December 9, 2013

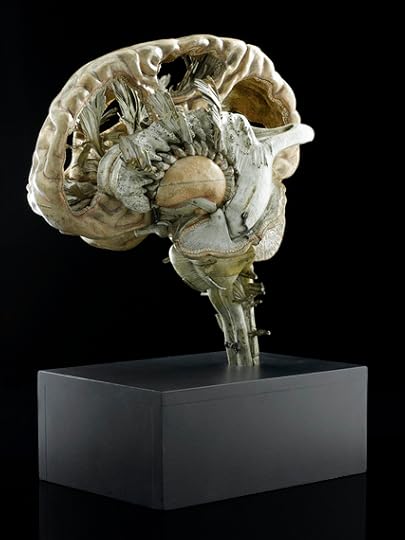

Science Museum Takes on History of Mental Illness Treatment in Compelling New Exhibition

Mental illness, how it is caused and what we can do to treat it is a pressing issue in contemporary society. Psychology has not always been perceived as a science in the outside world but in this fascinating - and free! - exhibition, the Science Museum has brought the scientific assessment and treatment of mental illness centre stage.

Mind Maps focuses on how mental health conditions and other psychological disorders have been treated over the past 250 years, from its crude beginnings in the 18th century through to the present day. The exhibition shows how far we have progressed in our understanding of the mind and how treatments for mental health conditions have evolved.

There is a wide range of exhibits on show. Some of these are fascinating, such as the sound of electrical signals in the brain and how these change drastically during a seizure. Others, inevitably, are quite traumatic. The controversial treatment of ECT (electro-convulsive therapy) is included, as are exhibits of an ECT machine and the gags necessary to put into a patients' mouth.

What is fascinating is how these eye-watering and wince-inducing approaches (and that's just looking at it. I'd hate to think what it was like for the patients) have developed our understanding of how nerves relate to thoughts, behaviour and mental health. Therefore is it possible that if we tackle nerves, we can impact mental wellbeing?

An early connection between nerves and electrical stimulation to impact the brain was the thinking behind Luigi Galvini's pioneering experiments in the 18th century. Galvini passed electric currents through animals, famously making a dead frog twitch even when it was electrically insulated from the generator.

If all of this sounds eerily familiar to the non-science specialist that's because Galvini's experiments, and in particular a more ambitious demonstration given by his nephew Giovanni Aldini in London in 1803 on a human corpse, was the inspirational spark for Mary Shelley's Frankenstein.

There's certainly a shadow of man playing God across a lot of this exhibition but it's also apparent that we have come so far in our understanding. Yes, our nerve impulses affect our sensory perceptions. And our nerve impulses can be affected by electricity. But there is so much variation from person to person, hence the expansion into pharmaceuticals and biochemistry, as well as therapeutic treatments.

So there is humility in this exhibition also. Science doesn't claim to have all the answers - not yet. As with so much in science, there is still so much more to know.

There's much set aside in this exhibition on alternative, non-invasive methods such as Freud, who was a nerve doctor but rejected this in favour of psychoanalysis. There are self-help books also and, fascinatingly, a glimpse into innovative new methods such as avatar therapy, where patients who hear voices are able to talk about their experience through the use of avatars.

Mind Maps really is a superbly curated exhibition on an extremely topical subject. The quality of the exhibits and the narrative alongside them, illuminating the visitor with so much more insight, follows on from other high quality exhibitions at the Science Museum such as the fascinating Collider exhibition (which is still on) and the wonderful Alan Turing exhibition.

The push from the Museum to challenge itself and deliver such accessible exhibitions on a range of topics is highly commendable and gives hope that more and more people and families will enjoy visiting the Museum.

Science Museum, London

To June 10, 2014

Picture credit: Model of a human brain, sectioned, French, first half 19th century, credit Science Museum.

Published on December 09, 2013 07:58

December 7, 2013

Theatre Review: Jude Law Shines as Henry V

Henry V, the last of Michael Grandage's season of plays, is a glorious production. His interpretation of Shakespeare's story of a King possessed by his call of duty to lead his country to victory over the French, no matter the cost in blood, is a stunning drama that deftly combines bloody violence and emotional depth with witty comedy.

And at the heart of it is a truly, genuinely brilliant performance by Jude Law.

Jude Law's performance as Henry V is unequivocally the best acting performance I've ever seen from him. His Henry is full of contradictions - his possessive belief that he is blessed by God masks him to the tyrant he is. Yet he is a king as much at ease with the phenomenal power he wields as he is with his army of men drawn from the most desperate of backgrounds.

It is an authoritative, modern interpretation from Law. Henry's big speeches to his outnumbered army - "once more unto the breach, dear friends, once more" - are delivered with heartfelt emotion, with a meaningful connection to the men he knows he is dragging off to their possible death, which is so much more profound than the imperious versions we are more used to.

There are a couple of quizzical elements to the production - the decision to merge the characters Chorus and Boy into one may confuse those not familiar with the text. And the after the gut-wrenching massacre at Agincourt, the play turns quickly to farce as Henry tries, clumsily, to woo Princess Katharine of France, which is a little jarring.

But neither detracts from what is overall yet another brilliant show from Michael Grandage in what has been a superb season at the Noel Coward Theatre.

Chances are also taken in the design of the show. Whereas Nicholas Hytner transported his version of Othello at the National Theatre earlier this year to contemporary Cyprus and Jamie Lloyd moved his Macbeth to a dystopian Scotland, Michael Grandage has kept his Henry V rooted firmly in traditional Shakespearian design. His king sits on a wooden throne whilst around him the Catholic priests wander in their floor-skimming robes and caps. Everyone is in capes, cloaks and armour.

Also, in quite a contrast to the rich forest scenes that he created for A Midsummer Night's Dream, Christopher Oram has gone for a sparse Globe Theatre look for Henry V. Unvarnished wooden floorboards underfoot and minimal set design. Set off with some very impressive use of lighting from Neil Austin to create texture through colour, I liked it. But I couldn't help feeling a trick had been missed.

Jude Law is incredibly impressive in the title role, yes, but one of the main advantages to star casting in is that it brings in people to the theatre who might not otherwise come. And that is great. I applaud star casting. Theatre needs it to survive. But do I think that those who flock to see Jude Law in this will think, 'ooh, I loved that. Let's go and see more theatre?' I'm not sure.

By keeping the production so traditional, it kind of reinforces a lot of people's fear and dislike of Shakespeare - that it's all in very plain settings, with lots of people in tights and leather boots spouting verse they don't really understand.

One of the great benefits of going to see a show not on press night is that you get to witness how non-theatre critics i.e. real people, respond to the play. At the interval, there were a few hushed whispers of "did you understand that?" and I couldn't ignore the handful of audience members who had fallen asleep.

I loved this production, I really did. It was full of pace, the dialogue was brilliantly interpreted and brought to life by the cast, and the production had moments of genuine heartfelt drama and laugh-out loud comedy. I just hope everyone else who goes to see this feels the same, I really do. Fingers crossed.

Michael Grandage Company, Noel Coward Theatre, London

To February 15, 2014

Published on December 07, 2013 05:07

December 6, 2013

Theatre Review: Let The Right One In, Royal Court

The much anticipated stage version of Let the Right One In is terrifying - but not emotional. There is a lot of excellence in this adaptation of the cult film but, crucially, it lacks heart and soul - somewhat ironically in a story about the undead.

Based on an extraordinary film, Let the Right One In is a dark, dark story about a teenage girl, Eli, who arrives in a small town with her 'father.' She strikes up a friendship with the boy in the apartment next door - Oskar. Oskar is an insecure lonely boy, bullied by schoolmates and propping up an alcoholic mother. Eli becomes his only friend, his confidante, and the two lost souls bond.

But the friendship is jeopardised by Eli's dark secret. She is a bloodthirsty vampire who must kill to survive.

For the play adaptation to succeed, it has to be dark, it has to be haunting, it has to be bloody and you have to care about the future of these young star-crossed lovers. And there was plenty of blood.

The manifestation of blood is superb. Yes, the violence of the throat cutting and the stabbing was vivid and wisely retained. But the generation of blood away from physical conflict, such as when Eli bleeds every time she enters a room uninvited, was incredible. I was so pleased the production did not hold back on its depiction of the horror in this story.

However this does mean I have some reservations on the Royal Court's promotion of this play to teenagers from 13 upwards. There is a very liberal use of the c-word in some places and the violence is vivid so some adults may be uncomfortable with younger teens seeing this. The film was 15-rated for a reason.

The set design was also superb. The stage is covered with snow and trunks of elm trees reach high up into the rafters. Under their branches, the stage doubled up as the dark of the forest and versatile interior settings such as school swimming baths, bedrooms and hospital wards.

The score is harsh, foreboding and a perfect accompaniment to a play where danger lurks around every corner and in the soul of every character. But though the play is a pulsating, violent achievement, it struggles with an emotional core.

The young actors behind Oskar (Martin Quinn) and Eli (Rebecca Benson) are superb in technical areas. Benson's jerky convulsions as she battles to control the killer within her are extraordinary. An actor twice her age and with twice her experience would be proud of such a performance.

Also Quinn really brings out Oskar's troubled soul, his growing pains, without him ever becoming wimpy and a caricature.

But the leads struggle to develop any chemistry between them. This story is of two lost kindred spirits coming together against almost impossible odds but there is little of that tenderness here.

Perhaps they are not helped by a script that is trying to do too much. Jack Thorne's writing retains much of the horror of the film but it is more a transfer of the movie rather than an adaptation for the stage. As a result, the production has a frenetic pace in an effort to squeeze it all in which prevents a foreboding emotional, steady build up to the terrifying climax.

Nevertheless Let the Right One In is a phenomenally ambitious piece of work and there are many achievements throughout it. It is good, very good. But because it didn't grab my heart I cannot claim I found it excellent.

Royal Court Theatre, London

To December 21, 2013

Published on December 06, 2013 02:02

December 5, 2013

Theatre Review: Emil and the Detectives, National Theatre

Emil and the Detectives is a bright, exciting adventure that has as much entertainment for adults as it does for kids.

Set in Weimar Germany, Emil is a young boy from a small rural town who has been sent to the city by his mother with one single responsibility - to safely hand over the 140 Marks she has saved all year to his grandmother.

But on the train to Berlin the money is stolen from Emil by a stranger - Mr Snow. But determined not to let his mother down, Emil sets out to conquer the hostile world of the capital city, track down the elusive Mr Snow and take back what is his.

This is a journey of discovery and of coming of age for the young Emil but it is also a story of new friendships. For even though Emil is alone in the City, he soon develops friendships with a wonderful cast of children, the kids of Berlin, who come to his aid.

1920s Berlin is wonderfully realised in a set designed by Bunny Christie. The hurly burly of the big city is crafted by both projections of vintage maps and grainy photos on the back of the Olivier, as well as an ever-changing world of street-lamps and sewers across the stage.

Of course it wouldn't be a faithful portrait of Weimar Germany without the cabaret. There's a glimpse of the singers and the dancers in the Berlin night. And the whole production is accompanied by a musical score from Paul Englishby which really adds to the flavour and energy of the show.

And the dialogue is snappy and funny; full of pace and wisecracks. It's a brilliant adaptation by Carl Miller that doesn't patronise but educates as well as entertains.

The main attraction though is the cast of children - the first time the National has worked with child actors. They are full of energy and spirit and there are a few stand-out performances, in particular Georgie Farmer as the cheeky Toots and Izzy Lee as the street-wise Pony.

The production is strong throughout but it really engages in the second half as the audience becomes more involved in the show - and as the show becomes more involved with the audience as the cast runs amok through the theatre in the climatic chase scene to catch Mr Snow.

The play is aimed at kids, much like War Horse and His Dark Materials before. But though Emil and the Detectives does not achieve the heights of these two shows, it was nevertheless great entertainment for all. There were a lot of kids in the audience and to see them so enthralled by the production was great.

National Theatre, London

To March 18, 2014

Published on December 05, 2013 03:39

December 4, 2013

Arts Review: The Snowman, Sadler's Wells

This production of The Snowman, a joint production by Sadler's Wells and the Birmingham Repertory Theatre, is a joyful festive treat that is entertaining for both children and adults alike.

Based upon Raymond Briggs' much-loved book, the story is one we all know. A young boy, James, wakes up one December morning to find the world outside covered with snow. Overjoyed, he rushes outside to play and build a snowman. But eventually playtime has to end and so James is dragged inside to go to bed.

But that night, unable to sleep, James peeks outside at the snowman he created only to find the snowman has come to life. And from here an exciting adventure and magical friendship begins.

The Birmingham Repertory Theatre production has worked hard to keep this production fresh even though it is returning for its 16th consecutive season at the Peacock Theatre. There is humour, wonderful sets, terrific costumes and a warm, festive spirit that cannot be denied.

The set design (Ruari Murchison) is bright and creative. And the variety of landscapes created as James and the Snowman travel the world is terrific. Whether it's kitchens, deep freezers, bedrooms, forests or even Lapland, each world is brought to life with great creativity and flair.

And with no dialogue at all, the story is told visually - through acting and dance - and through the timeless, emotive score from Howard Blake.

The cast are superb and show great versatility. There are ballet-dancing princesses, there's limbo dancing fruit, there are marching toy soldiers and of course there is flying. The audible drawing of breath and cheering as The Snowman took James in his arms and took flight was really quite something.

The Snowman is a wonderful alternative to the usual Christmas entertainment for children of either clichéd pantomimes or The Nutcracker ballet, which can go over the heads of many children. The Snowman even managed to put Christmas cheer into a cynical arts & culture critic such as me. It really is a wonderful show and at under 2 hours, the perfect length for children.

Magical.

Sadler's Wells, Peacock Theatre, London

To January 5, 2014

Published on December 04, 2013 06:00

November 29, 2013

Theatre Review: Gastronauts, Royal Court Theatre

Gastronauts is a fun, innovative and absorbing production that looks at our relationship with food.

Created by April De Angelis, Nessah Muthy and Wils Wilson, this immersive theatrical production seats its audience in a futuristic restaurant whilst around them little snippets and scenes are played out by the small cast.

The purpose of the play is to examine our relationship with food. How we connect to it emotionally, how we have perverted its production to satisfy mass consumption and how those at the end of the scale - the farmers and workers - are exploited for financial gain.

The decision to make this an immersive experience, with audience participation, is a smart one. Tasters and canapés are distributed around and the audience is encouraged to appreciate the food with all their senses, to reconnect with food not just as fuel but emotional fulfilment. It prevents the piece being sterile and a lecture rather than a show.

The futuristic fine-dining set by Lizzie Clachan has a great dystopian feel to it, which is a perfect partner for the writing as the play descends into its dark centre where we are forced to realise where our exploitation of our natural resources is leading us.

The piece is well directed by Wils Wilson. It's pacey and the audience really is at the centre of the action as the cast use all the space available to play out the drama.

The small cast (Andy Clark, Imogen Doel, Nathaniel Martello-White, Justine Mitchell and Alasdair Macrae) work hard and show great versatility. The production combines light-hearted musical numbers with emotional drama and all the cast handle the audience participation with humour.

As always with theatre that has an explicit message - in this instance, how our mass production of food is destroying our own health and our balance with the natural world - there is a fear that the desire to make the point overcomes the dramatization.

Sure, some of the playlets are better than others. In particular, the running plot throughout the evening of Imogen Doel's character battling her food demons is the piece with the most emotional heart and the most engaging. But overall, Gastronauts strikes a fine balance, ensuring there is always more 'show' than 'tell'.

To December 21, 2013

Jerwood Theatre Upstairs, Royal Court, London

Published on November 29, 2013 03:44

November 27, 2013

Theatre Review: Nut, National Theatre

nut is a mesmerising production that brings to life the difficult subject of mental illness in a unique fashion, combining sensitivity and compassion with humour in a very sharply written play.

Elayne (Nadine Marshall) is a complicated woman. She wants to be alone but she desperately needs friends. Only the friends she has Aimee (Sophie Stanton) and Devon (Gershwyn Eustache Jnr), are as cruel as they are kind. She doesn't leave her house and spends her time writing her eulogy and planning her funeral.

Her sister (Sharlene Whyte) isn't much help either - too busy both keeping a distance and absorbed with her own problems with her ex-husband (Anthony Welsh).

You'd think that from that intro that nut is a dry, overwrought piece but you'd be wrong. Yes this is a play about mental illness - hence the play's title - but nut is a witty, well-structured play that is completely absorbing.

Written by Debbie Tucker Green, the subject matter is handled quite brilliantly. It would be so easy for this play to be ridden with clichés or to tread over familiar ground but Green's approach is dynamic yet sympathetic. Nor has the writing fallen into the trap of being heavy and dry. The piece is fast, funny and powers though its 75 minute running time.

The characters Green has created are complicated and full of contradictions. In that way they are perfectly realised. At times harsh and snappy, at other times warm and supporting.

Yet there is also real sensitivity and depth. Elayne, a brittle and fragile woman, and her complex battles are brought to life in a challenging way. Marshall does a superb job in the lead role, bringing real depth and warmth to a woman who spends her life pushing people away.

The whole cast is excellent. Green's dialogue is challenging - stylised and often overlapping - but the actors seem to have taken to it with ease. Each character was multi-dimensional and existed with purpose.

The play is being shown in The Shed, the National Theatre's temporary space that won the 2013 Empty Space award. Green, who also directs, makes great use of the black box studio.

She is supported with a terrific set design from Lisa Marie Hall. Tubes and girders balanced precariously, suspended from the ceiling, are a perfect manifestation of the inner turmoil of the characters.

A brave, daring production that succeeds in captivating its audience.

To December 5, 2013

The Shed, National Theatre, London

Published on November 27, 2013 02:58

November 26, 2013

Arts Review: Art Under Attack, Tate Britain

From Kings to suffragettes, from the IRA to artists themselves, there is a long history of art being the focus of attack both from the state and from the public. This history of iconoclasm, or image breaking, is captured in this wide-ranging and fascinating exhibition at the Tate Britain.

The first part of the exhibition examines the state-led destruction of art, most notably under Henry VIII where Roman Catholic art and icons were systematically destroyed as part of the Reformation. The exhibition includes sculptures from Abbeys of decapitated Virgin Marys and anti-Papal propaganda such as Girolamo da Treviso's A Protestant Allegory of evangelists stoning the Pope.

Given that it is estimated that over 90 per cent of medieval sculpture was lost during this period, the remnants give an idea of the scale of destruction caused during these years.

The second part of the exhibition looks at how visible works of art have been the focus of attack as a political protest against the state. The suffragettes famously used attacks on art in museums and galleries as a means of drawing publicity to the fight for female suffrage. Though they were criticised for it at the time, their success in creating headlines was noted by other campaigns such as the IRA who adopted similar methods.

Where the art that was attacked is no longer available, the exhibition has used other means - photographs, newsreel and radio recordings - to convey the damage caused. Of particular interest were the news reports of the IRA destruction of Nelson's Pillar in Dublin in 1966. This statue, along with the Equestrian Statue of William III, were seen as very visible symbols of British rule and were the focus of many smaller scale attacks before both were eventually destroyed completely.

I also enjoyed very much the interview with Mary Richardson, the suffragette who slashed The Rokeby Venus in 1914 in protest at Emmeline Pankhurst's imprisonment. The painting has been so well restored as to make the slashes from Richardson's meat cleaver almost invisible. The Tate Britain has therefore included photos in the exhibition of the damage from the time.

The interview with Mary Richardson from 1961 portrays a woman unrepentant of her actions and gives a fascinating insight into what motivates people to attack certain pieces of art and what impact they hope to achieve.

If you are particularly interested in the suffragettes, it is worth noting that there is a separate free exhibition also at the Tate Britain of the work of Sylvia Pankhurst, Emmeline's daughter and artist behind many of the militant suffragettes' most striking images.

The final part of the exhibition looks at how contemporary artists themselves are transforming pre-existing images. An interesting example was from the work of Kate Davis who traced parts of her body over copies of Modigliani's work as a response to his idealism of the female form.

Only this year Constable's The Hay Wain was attacked by Fathers 4 Justice to draw attention to their cause proving that art continues to be the focus of political protest.

To January 5, 2014

Tate Britain, London

Picture caption details: Allen Jones, Chair 1969, Tate © Allen Jones

Published on November 26, 2013 09:33

November 25, 2013

Opera Review: Madam Butterfly, English National Opera

To witness Anthony Minghella's Madam Butterfly is to witness the best visual theatrical production opera currently has to offer. I therefore welcome this revival at the London Coliseum with open arms.

Madam Butterfly is a story that has become well engrained in popular culture over the 100 years since it was first performed. Cio-Cio San, Madam Butterfly, is a young geisha girl who marries an American Naval officer, Pinkerton, whilst he is stationed in Japan. But whilst the marriage is just a fling for him, it is deep life-changing love for Madam Butterfly. So when her husband soon flits off back to America, Butterfly waits patiently for his return.

Though it is patently obvious to all around her that her love for Pinkerton is unrequited, Butterfly refuses to believe it. Until of course Pinkerton returns - with his American wife - and Butterfly's heart is crushed beyond all hope.

Even though it is now eight years since Anthony Minghella debuted his interpretation of Madam Butterfly, still no opera has matched its extraordinary theatrical achievement. It remains the benchmark.

This revival is beautifully directed by Sarah Tipple who honours all the original elements of Minghella's version and builds on them. The production begins with an elegant and graceful geisha fan dance, performed in silence. Its beauty and its faithful representation a bold marker for what follows.

The set design from Michael Levine is wonderful, as are the costumes designed by Han Feng. Dancing geishas, the blood-coloured rising sun, Japanese lanterns, binraku (Japanese puppet theatre), cherry blossom and fire flies... The production matches the 'East meets West' approach of Puccini's score and brings an intriguing and intoxicating exotic quality.

The title role was played by Dina Kuznetsova, who was making her ENO debut. A great actress as well as a terrific soprano, she brought real childlike naivety and tenderness to what can be a very one-dimensional character. She is a performer with a great stage presence and star quality.

Timothy Richards who played Pinkerton too had a great emotional depth to his voice but it did not have a lot of power. Occasionally he was drowned out by the orchestra, which was conducted by Gianluca Marciano, who was also making his ENO debut. Marciano certainly wrung all the drama out of Puccini's score but perhaps needed to give the singers on stage more opportunity to be heard.

The production is sung in English, which has raised some eyebrows. I appreciate that many would like opera to stay faithful to the language in which it was written (in this case, Italian) but given that I, for one, am incredibly keen for opera to find a broader, more diverse audience, I'm all for changing the language providing the translation fits the musical line.

Surtitles are still provided but I thought the translation worked well. At times dramatic and poignant, but also with moments of humour to keep the tone varied. A couple of lines in the libretto were a bit out but barely noticeable. I thought it was a brave decision that largely paid off.

Opera needs to take risks if it is going to compete in a packed entertainment market and so I applaud both the intention and the result.

For me the only downside was that it wasn't a real tear-jerker. Maybe it's because I am so familiar with the story or maybe it's because Butterfly is such a victim it's hard to feel empathise with her. Nevertheless Minghella's version of Madam Butterfly really does take your breath away. It remains well worthy of all the praise that has been lavished on it.

To December 1, 2013

The Coliseum, London

Published on November 25, 2013 06:13

November 21, 2013

Theatre Review: Theatre Uncut, Young Vic Theatre

Theatre Uncut was established to encourage debate and galvanise action around political issues. To enable that, they have produced a series of short plays, presented in one show, which are all based on the current political landscape.

The six plays that make up the show at the Young Vic cover issues such as the Occupy movement, banking, tax havens, racism, feminism, coalition governments and immigration. All well worthy subjects for discussion.

However, the challenge with explicitly political theatre is to not let the desire to get the message across overwhelm the theatrical performance. That old maxim 'show, don't tell' has lasted for a reason and there is an awful lot of 'tell' in this production. At times I felt as if I were in a lecture hall rather than a theatre.

The six plays were a mixed bag. Most of them were guilty of not having enough conflict in them, or being one-note productions where the tone of the debate between the main characters never varied or turned. And there were too many clichés.

A political activist mocking scatter cushions and John Lewis is a cliché. A Sun-reading EDL supporter arguing with his University graduate daughter is a cliché. A right-wing white American politician who wants to get rid of all black people is a cliché. Characters should still have depth and contradictions even if they exist solely to make a political point.

However there were two outstanding pieces in this show which, for me, just about made the evening worthwhile.

Recipe (written by Rachel Chavkin) was an extremely sharp and innovative satire of coalition politics, with the politicians reduced to little more than posturing, squabbling children as they battled for supremacy. It was a well-observed piece with a lot of energy which made for a great contrast to some of the more dry, static pieces in the rest of the production.

And Church Forced to Close its Gates After Font Used as Wash Basin (written by Mark Thomas) was a brilliantly written and witty piece on a newspaper editor, one who bore an extremely close comparison to Richard Desmond. He's after a place in the New Year's Honours List but his plans come apart at the seams when he is taken hostage by people unhappy with the aggressive right-wing agenda of his newspaper.

Theatre Uncut is a worthy global initiative. It's important that theatre can be used as a means to spark debate on issues and events in the current political landscape. However you have to be careful about being too forgiving just because it's a good cause. After all, the audience is still being charged to see the show.

There is a lot of promise in Theatre Uncut but it does need to invest in more pieces of high quality if it's to engage its audience in the way it wants.

To November 23, 2013

Young Vic Theatre, London and worldwide

Published on November 21, 2013 03:20