R.J. Lynch's Blog, page 19

August 1, 2014

Am I nuts?

I’m editing Poor Law, the sequel to A Just and Upright Man and second in the five book James Blakiston series. At least, I thought I was. But a couple of days ago a series of strokes of the sort of genius known only to the greatest minds meant I had to accept that I was into a wholesale rewrite and not just an edit. I’ve spent a large part of today in 18th century Durham county, the POV I’ve been writing these scenes in is that of a young woman and I got into that trance-like state that comes—sometimes—when it’s going well, you’re undisturbed and you’ve left your own world behind and moved completely into someone else’s. If you like—though it’s a word I don’t like—I’ve been channelling a sixteen year old girl from the 1760s. A number of things happened and Kate told me each time how she felt, what was in her mind and what the reaction of other people was. Times like that you have to keep going, keep writing because you don’t know when you’re going to have that rock-solid connection to another world again. When I finally came out of it (because I needed to eat) I was reminded of that time I’d been writing a 20th Century criminal and, when I finally stood up, I was patting my pockets, desperate for a cigarette. It took twenty minutes before I remembered that I don’t smoke.

That took me on to Zappa’s Mam’s a Slapper, where protagonist Billy McErlane stood over me while I was working telling me, “Don’t forget the anger management. Tell them about the psych. Wendy wouldn’t have behaved like that, she’d have done this.” And from there it wasn’t a huge step to When the Darkness Comes and Haile Selassie elbowing his way forward when he caught the scent of Barabbas (who he didn’t care for one little bit) and saying, “If he’s in, I’m in.” The Lion of Judah had no place in my plans but he wasn’t going to be denied. He took control, too. So I suppose the question is fairly obvious. Am I completely round the bend? Is there any hope?

True to Life? Or Photoshopped?

True to Life? Or Photoshopped? March 4, 2013 By sfhopkins

Some of my favourite writers are those who appear to draw their characters from life – warts and all. But I did say “appear”. Because many of the stories that are most true to life are, to a great degree, invention. Jane Austen, for example – you don’t read her books so much as inhabit them. The people are real, the buildings are real, the motivations are entirely believable and I have no doubt that there was a basis of observed reality there but what made her such a consummate artist was what she did with that reality.I started mulling this over when a friend in England sent me this picture of Cartmel Priory. He and his wife had been to a restaurant there to celebrate his birthday and he shot this. His email told me how beautiful the Priory was – and all I could think was, “How could you leave it like that?” I left it, too – not my picture, not my problem – but I was irritated. Irritated enough to come back to

it and remove those horrible, ugly bins. I ended up with this.

Then I sent the pic back to my friend with a message saying, in effect, “I’ve fixed it for you.” And now he was the one to be irritated. He had sent me “an accurate portrayal of how it actually was” and in return he had received “a glossed up olde-worlde picture of how you’d like it to have been. A FAKE.” (Olde worlde? I can see two cars, for Heaven’s sake).

I’d like to say I was hurt but I can’t because I don’t get hurt easily. I did, though, ponder the question of expectations. Then I asked my friend what was the last novel he had read and he said he couldn’t be sure but he thought it was Lord Jim by Joseph Conrad which had been a set book at school several decades ago. He hadn’t enjoyed it and was in no hurry to repeat the novel-reading experience.

And that, I thought, was it. Those of us who like fiction want to see reality, yes; but we want a form of reality that has been processed by the artist. What we want is the reality behind the reality. Which is what I thought I was doing when I removed those dreadful bins.

via True to Life? Or Photoshopped?.

July 10, 2014

Between Women

I was in that place I knew so well that I’d always thought of as Between Women. And then I realised that I wasn’t.

I’d been between women several times in the past, and always with a combination of sadness and hope. Sadness that a love affair was over, because I was completely invested in a relationship while it lasted. Or I thought I was; the woman often disagreed, which was sometimes the reason it was coming to an end. And hope at the idea of being able to put myself out there once more in the hunt for someone new. Someone somehow indefinably better. Someone with whom, this time, the train of love would not slam into the buffers.

That was the nature of the experience of being between women.

And, this time, it didn’t apply.

About six years earlier I’d talked to the doctor about sleep difficulties I was having. I don’t mean going to sleep, I could still do that, but staying that way instead of waking at two in the morning. The doc suggested testosterone therapy and I said, ‘You have to be joking. Almost all the trouble I’ve had in my life, all the stupid things I’ve done, were caused by too much testosterone. And now, when it’s finally receding, you want to top it up. No thank you.’

And it was the right decision because, after a while, I started sleeping through the night again.

I’d been glad that the hormonal flood was reducing, the tide of aggressive maleness ebbing, the risk of behaving like a damn fool diminishing. What I didn’t do was to think through the likely consequences. I didn’t need to at the time, because I wasn’t going to see them for another six years, but now here they were.

I’m not talking about impotence; I could still do the lady justice if I wanted to, no Viagra needed, thanks very much. I just didn’t want to.

I didn’t suddenly wake up and find I’d gone off the whole idea. What happened was that I met a new woman, a very agreeable woman, just turned fifty, a nice age difference, and I took her to dinner. It was a good dinner. Nice restaurant, attentive service, food better than normal. The conversation was good, too. Easy. Agreeable. Unstressed. You don’t always get that on a first date. We had a lot in common. Including, as we found out towards the end, a mutual love of cheese. Cheese is usually more a man’s thing than a woman’s. A lot of women see it as fat they don’t need to ingest. But the restaurant had an excellent British cheese board, and she got into them as much as I did and we found we were talking about cheese: Cheddar; Perl Wen; Sage Derby; Shropshire Blue, and then I said, ‘What a friend we have in cheeses,’ and she laughed.

It was a lovely laugh, whole-hearted and not tinkly or forced, and I think she knew it wasn’t originally my gag, that it had been around a while, and maybe she was just encouraging my willingness to make an evening of it, showing hers too for that matter, and maybe she was someone who laughs easily. I like people like that, men or women, especially when I’ve just met them because then you get a chance to rework all your old material. Good salespeople have their material, you know, just as professional comics do.

So I ran off a couple of the classics. Like the one about being expelled from school because of that unfortunate incident in drama club when I misinterpreted the stage direction, Enter Ophelia From Behind.

Her laughter was completely in the moment. Unforced. And all the time I was thinking, ‘Oh, God, I hope she doesn’t want to go to bed.’

I don’t think I’d ever thought that before. Not since I was eighteen and I’d gone for a curry with my first girlfriend, can’t even remember her name now, curries being the new thing for most English people when I was eighteen, and not with all the girls and then women since; not once have I ever hoped the one I was with wouldn’t want to go to bed with me. Mostly they didn’t, of course, especially in the early days because girls played by different rules in the Sixties, whatever you may read. And that first one certainly hadn’t. But that was not what I wanted.

And now it was.

Don’t ask me to explain it. I’ve never been good at the great existential questions. I’m a salesman, a good one, and when I’m working and I meet someone for the first time I think, ‘Is there a sale here?’ and if the answer’s ‘No,’ I’m out of there as soon as politeness allows but if it’s ‘Yes,’ or even ‘Quite possibly’ I know I’m not leaving till I’ve got it. But to explain other things, like why I’d suddenly stopped wanting something I’d always wanted in the past, well, I can’t do that.

I think she did, actually. Want to go to bed, that is. Or I think she was willing to, at the very least. I say that because she didn’t look happy when I did my thing with the iPhone. I’d paid the bill, left a tip, walked her home and the look on her face said she was about to suggest coffee, which as we all know may be an offer of a cup of coffee and may mean something else entirely, and I took the iPhone out of my pocket. I said, ‘I hate it when these things vibrate like that. It’s why I never carry it in my shirt pocket. I’m afraid it’ll have my nipple off.’ She smiled, but I wondered if she realised that every word I’d just spoken was untrue and I’d said it to let her think my iPhone had vibrated, which it hadn’t, and that someone had contacted me, which was not so. Then I pretended to read a text message which didn’t actually exist, and then I said what a great evening I’d had and how I hoped we’d do it again but right now I had to run because someone needed my help. I couldn’t read her facial expression but she wasn’t happy. But she agreed we’d had a good time and I should call her and maybe we could do it again. Then she turned away, put her key in the lock and went inside without a backward glance.

* * *

Of course I wasn’t going to call her, whatever we may have said, and I suppose I thought I’d never see her again. But she rang me. She was throwing a party, just a little thing for old friends, nothing elaborate but it would be fun and she hoped I’d want to go.

You don’t have much time to think of a response to something like that; any hesitation sends its own message; we’d had a good evening and I’d enjoyed her company so I said yes, I’d like to go to her party. She gave me date and time, we exchanged pleasantries and hung up. It wasn’t all pleasantries because she said, ‘Leave your iPhone at home.’ So she had known I was lying, but she was prepared to give me a second chance.

* * *

One of the difficulties with parties is: flowers or wine? I decided to play safe and do both. I had the flowers delivered the morning of the party so she’d have a chance to put them in a vase and straighten them out, fluff them up or whatever it is that women do with flowers. I took the wine with me. My wine rack has the really good bottles on the lowest level and the stuff I’d give to people I didn’t really like on the top. It isn’t bad because what would be the point of buying bad wine? It just isn’t memorable. Or pricey. For the party, I took out a bottle from one of the middle shelves. Then I put it back and went lower down. All the way down. Don’t ask why because I don’t know.

When I put it in her hands she looked at the label and said, ‘I’m going to hide this. It’d be a shame to waste it on people who won’t know what they’re drinking.’ So she knew wine as well as cheese. My kind of woman. Would have been once, anyway.

It was a good party. If these were the kind of people she liked, I liked them, too. There was none of that competitiveness you often get at social gatherings—the “I’ve been to this place/read that book/met some power broker you haven’t” stuff that has so often made me leave a party early and I didn’t want to leave this one—I was having too good a time. In fact, I was still there at the end and when the last guests were preparing to leave I stood with them to thank Catherine—that was her name; Catherine—and go, too. As she was kissing the others goodbye she put a hand on my chest and said, ‘Stay a moment, will you? I have something you might be interested in.’ Then the door was closed and we were alone.

She turned to me. She was smiling and I thought there was an inquiry in her raised eyebrows but whatever the question was she didn’t ask it. Not right then, at any rate. She said, ‘I have to go to the bathroom. I won’t be long.’

When she came back, she’d got rid of the party dress and wrapped herself in a towelling dressing gown. There was a pleasing smell of soap. She said, ‘I’ve just washed my bits. Bidets are wonderful, aren’t they?’ She put her hands on my chest and kissed me on the cheek. ‘If you’d rather go, you can. I won’t be cross. We’d probably better not see each other again, though.’

That doctor must have been crazy. I didn’t need testosterone replacement; I had the stuff in plenty. I said, ‘I’d like to stay.’

‘Right answer. Would you mind washing your bits too, then?’

* * *

While you’re doing what we did that night, you don’t think about why you’re doing it. That came later and I found it intriging. The doctor had been right in a way; I did need something to boost my hormones. The something wasn’t chemical, though. What I’d lacked was desire, and I hadn’t had that because there had been no-one in my life I liked enough to want to take my clothes off. And now there was. When a young man says, ‘I love you,’ what he really means is, “I want to be inside you.” And he does. He wants to be inside her every day. He thinks that desire will be with him for ever, and when it dies—because it does die—he may make the best of what he has or he may look elsewhere in the hope of finding the same level of lust with someone else. But I’m an old man, or at least my father’s generation would have called me old, and what I need now is different. If I could talk to the young man I once was, when he looked at a new girl I’d say, “Hang on a minute. What are you going to talk about, when the sex is done?”

It would be pointless, though. He wouldn’t have listened, the randy sod. What he needed was what that bottle of wine I’d taken Catherine had. Time in the bottle. Age. Maturity.

I’ve got those things now. Catherine and I are happy together. I’ve looked all my life for contentment. You have to wait for that. I wish I’d known earlier.

Author’s Note

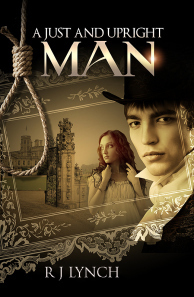

I’ve put this here as an example of how I write. If you don’t like my writing, that’s okay, we won’t fight about it. If you do, you might like A Just and Upright Man. And quite soon there’ll be Zappa’s Mam’s a Slapper. That isn’t out yet, though. If you’d like to know when it is, email me and I’ll let you know.

July 7, 2014

Enclosure. A necessary evil, but at such cost

The visible crises in A Just and Upright Man are the murder of Reuben Cooper and James Blakiston’s search for the killer, and Blakiston’s equally urgent wish to deny—to himself as much as to anyone else—that he is in love with Kate Greener. Those are the matters the book is concerned with. No-one, though, can get away from the troubles in the wider world that surrounds them and the threat of enclosure weighs on Blakiston and everyone else in Ryton.

We look back now on the enclosures in England in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries as things from which we benefited. At the most, necessary evils. In Poor Law, the second book in the series, Blakiston himself ponders on this: Times were hard for those without land, and getting harder. He was confident in what he was doing; future generations would be grateful for the larger farms, the transfer of strips of land in common ownership to more effective units, the modern farming methods that meant fewer people could produce bigger crops. Better agriculture would make the country richer, and so would the mining and manufacturing industries that were growing as men and women no longer needed on the land expanded the workforce in the towns and pit villages. Still, many of the people who had worked the land were paying a terrible price now for the benefits others would have in the future. The Rector would say that all was ordered for the best in God’s world, and the poor would have their reward in the life to come. Walter Maughan on the other hand would say that the poor were being punished by God for sins known to Him though invisible to us. But these comforts were not available to Blakiston.

Blakiston was a Sussex man before family ruin forced him to the northeast of England, and enclosure came to Sussex decades before it reached Durham. When his employer, Lord Ravenshead, asks what he knows of enclosure, Blakiston says,

‘My Lord, in Sussex all the land is enclosed. There are no common lands left.’

‘And have the enclosures been successful?’

‘For the landowners and the larger farmers, My Lord, yes. For the ordinary people, enclosure has been disastrous. They have been ruined. Cast out to make their living where and how they might.’

Tom Laws, a labourer whose marriage to Lizzie Greener brought him tenancy of a farm, knows nothing of this. We can feel his shock in this passage as he learns what the gentry can do to a hard working labourer:

‘We are poor men, master. The wife and me have three bairns still at home. You know how it is with us, for you were one of us not so long ago. Meal is dear and meat near impossible. Without the chickens and the pig and potatoes from the garden, and milk from the cow, we would starve. Now I must kill the cow because their lordships will take the common I feed it on. That land belonged to all of us and soon it will be theirs alone.’

‘It is hard, I grant. You will still have the chickens and the pig and the garden.’

‘Aye,’ said Zeke. ‘But for how long?’

‘I don’t understand.’ ‘What do you know of enclosures?’ asked John.

‘Nothing. I was never part of one. And neither were you.’

‘No. But my cousin in Barton, James Savile, he was in one. After the Act was passed the commissioners came to divvy up the land. James was to get a little piece to make up for everything they took away from him. So he didn’t have his grazing or his turbary but he would have some land. What they call his allotment. Not the best land, mind, the squire would get that, but land.’

‘Yes. That’s fair.’

‘Of course it is. But they had to pay for the fencing, see, man.’

‘Well, if you’ve got some land of your own, of course you have to fence it. You’ll be feeding someone else’s pig instead of your own, else.’

‘No, man. James didn’t just have to pay for his own little bit fence. He had to pay for the squire’s and the rector’s an’ all.’

‘No, John. No, that can’t be right.’

‘Right? We’re not talking about right, man. We’re talking about what’s in the Act, and who wrote the Act, and that wasn’t the cottagers and the squatters. It’s the squire and the rector and their pals in Parliament who wrote the Act. And that’s what it said. The squire and the rector and all them that were getting big bits of land out of it, they didn’t have to pay one penny for fencing. But all the poor little buggers that were getting enough land to raise a pig and grow cabbages, they’re the ones who had to pay for all the fencing. Their own and everybody else’s.’

‘I don’t believe it.’

‘You can believe it or not, man. It’s true. And that’s what’ll happen here an’ all. Mebbes Lord Ravenshead might be ready to pay for his own fences but yon greedy bugger in Durham Cathedral, he’ll not, the miserable Welshman that he is. And as for the Blacketts, who believe we are nothing…we’ll get no mercy there.’

‘So what happened to your cousin James?’

‘Exactly what they meant to happen when they wrote their bliddy Act. “Oh, James, man, can you not pay your bit fence money? Well, divven’t ye worry, man. We’ll help you out. We’ll buy your bit land off you for five pound and you can have yourself a nice drink and we’ll have all the land for ever. And you can forget about your bliddy pig.” And that’s what’ll happen to me and me pig and me cabbages and me chickens.’

‘I knew nothing of this,’ stammered Tom.

‘You know it now,’ said John Robinson. ‘We were wrong to talk behind your back. You are not our enemy.’

‘Mebbe not,’ said Zeke. ‘But I warn you, Tom Laws. Watch out for Isaac Henderson.’

‘Zeke’s right,’ said John. ‘Isaac hates you. If he can bring you down, he will.’ He stepped closer to Tom. ‘You are a fool to let him take your rabbits. It brings him onto your farm. He has big eyes, that one. He sees things he should not.’

Did I make that up? I did not. What John Robinson describes is exactly what some rapacious landlords did to swindle their labouring men out of the small pieces of land—the “allotments”—that the law said they should have. When I learned that while researching A Just and Upright Man I was determined to get it into the book and expose this awful piece of history to a wider view.

In Poor Law there is another insight into the effects of enclosure when Tom Laws, newly elected against his will as one of the Overseers of the Poor, tells Blakiston this:

It is not farmers who say that an old widow-woman must be removed to her place of settlement, a place she may not have seen since she came here as a young bride. It was not farmers who built the Woodside Poor House two year ago and said the poor must enter it or starve. But it is farmers who are made Overseers of the Poor and have to carry these things out on behalf of their betters, and farmers who get the blame. When a labourer has no work and must go to the mines or see his children sent as apprentices to some place from which they will likely never return, it is a farmer who has to tell him. Our people go off to the towns and the pit villages and they do not like it and they blame us.’

‘I am sorry.’

‘And when enclosure comes…’

‘…and it will come, as it has come everywhere…’

‘…people will see some farmers with big farms and many small men driven from the land. It will be the Bishop of Durham’s doing, and the Blacketts’ doing, and it is they who make money from enclosures but it is us the people see and us they blame. People have long memories. They remember not only their own grievances but those of their fathers and their grandfathers.’

Economic historians will tell you that enclosure paved the way for the Industrial Revolution, for two hundred years of world domination by the Royal Navy and for the birth of the United States of America as a bastion of freedom and I don’t doubt that all of that is true—but the price paid by the poor was a dreadful one.

June 8, 2014

Skinny Belly Dancers

Belly dancers in the Middle East were usually Egyptian or Lebanese and they were big. Not fat, necessarily–though some were–but there was plenty of them. For several years now, the ones you see in hotels and restaurants in the UAE have been from Brazil and they’re skinny. I’m sorry but I just don’t see the point of a belly dancer without a belly. When they get going you want to feel that if they let go just a little more, spin just a little faster, they’ll have a chandelier off the wall. Something has gone out of the world and I, for one, don’t like it.

May 13, 2014

Where did that come from?

When I’d finished A Just and Upright Man, I wanted to start on something different—a story set in the 21st Century instead of the 1760s. I sat at my keyboard and waited to see what would come. It was this: All I’d said was, I wouldn’t mind seeing her in her knickers. I sat and stared at the screen. Where on earth had that come from? I really didn’t have a clue. People ask, “Where do you get your ideas from?” and in this case I’d have had to say, “I haven’t the faintest idea.” And I didn’t.

But somebody did because the story, which became Zappa’s Mam’s a Slapper, developed—and, while it did, someone was talking to me. It took me a while to identify the someone as Billy McErlane, narrator and hero of Zappa’s Mam’s a Slapper. He was so heavily invested in the story that he kept prompting me: “Tell them about the anger management”; “Don’t forget the psychologist”; “Don’t say that, because that isn’t really how it was.” By the end of the book I knew as much about Billy’s life as Billy did. I knew how he’d felt when Wendy dumped him; I felt his fear as he watched The Creep being beaten to death and his impotent fury at the lies told about him in court. But I still didn’t know where all this was coming from. Who could possibly be telling me all this?

And then I remembered that time while I was writing When the Darkness Comes—a book so complex in design that it still after four years isn’t ready to meet the public—when Barabbas walked into the Canaries hotel where a TV chat show was being filmed and Haile Selassie arrived out of nowhere in a very bad temper to tell me what I could and couldn’t do with a man he regarded as a usurper.

That was a sobering experience. One result is that, when people do say, “Where do you get your ideas from?” I don’t attempt to tell them because I know they’d think I was nuts.

Now where would they get that idea from?

(If you’d like to know when Zappa’s Mam’s a Slapper is published, and/or if you’d like to subscribe to the Mandrill Press Newsletter (which will tell you that and all sorts of other interesting things), email me on rjl@mandrillpress.com and let me know).

March 13, 2014

Can you write when you can’t write? Tools of the trade.

In a long career as a salesman, I established that I needed the following things to succeed:

• Resilience, since the best salesperson in the world (and who better than me to tell you this?) hears “No” more often than “Yes”

• The ability to hear the things people don’t say

• Good product knowledge

• To listen more than I talked

• A cast iron stomach

• Excellent command of the language (English in my case)—written and spoken

I’m not suggesting that all salespeople have all of those things—I’ve met a great many who lack one or two of them and a few who called themselves salespeople who didn’t have any—but the good ones have most of them (the cast iron stomach is only necessary if, like me, your chosen field is international sales; I’ve lived and worked on every continent except Antarctica and some of the things I’ve been given to eat—especially in Asia—have been a challenge). That, resilience and the ability to hear the things people don’t say are gifts; you have them or you don’t. The others—product knowledge, listening more than you speak and written and spoken language skills are tools of the trade and no-one who wants to hit target should leave home without them.

Writing works the same way—or so it seems to me. You may or may not have the understanding of human motivation that allows you to create believable characters, or the ear that means you can write good dialogue, but there are things that you must have and I believe that a perfect grasp of grammar, punctuation and meanings of words are among them.

Patrick Hodgson was a salesman of the first rank as well as a good friend but, like most Lancastrians, he believed in blunt speaking. As in, “S/he’ll never be able to sell as long as s/he has a hole in her/his arse.” Not polite, but I always knew what he meant and I usually agreed with him; and, sometimes, I’m tempted to apply the same judgement to some of the writers I meet on line. I don’t, though, because I can never forget two writers who, when they began, were appalling and all their friends told them so. George Orwell was one and I’m the other. So, I would never say “never” when it comes to a person’s ability to write. S/he maybe can’t write now, but that doesn’t mean it will never happen for them if they work at it hard enough.

Sometimes in the groups we belong to we read a post so full of errors that we’re tempted to pass the Patrick Hodgson judgement. Well—I am, and I suspect I’m far from alone. I notice that these posts are usually either ignored or met with courteous responses and that is as it should be; I’ve no time for people who write replies that insult or demean the recipient. “If you’ve nothing good to say, say nothing” is good advice.

A while ago, I looked at a piece of work by someone whose first language was not English and who wanted an editor who could help her rewrite her novel to look as though it had been written by an Anglophone. I gave her the best advice I could: You’re not ready to spend money on that kind of editing. Join a local writing group. Learn about Point of View, Structure, Characterisation, Show Don’t Tell. I didn’t hear from her again and I have no idea whether she took it, but it was the right advice for her at the time.

Yesterday, though, I read a blog post that I was convinced was a spoof. I wrote the author this message: Look, I have to ask a question and I mean it to be taken seriously. I’m not a troll and I’m not attacking you—I’m just so astonished by what I have read that I have to ask for clarification. You say “forum’s” when you mean “forums”. You say “I may even of mentioned” when you mean “I may even have mentioned”. You say “Amazons feet” when you mean “Amazon’s feet.” And so on. These are marks of the semi-literate—the person who’s submission would not hold an agent’s or publisher’s attention beyond the first para. But you present your blog as a writer’s blog and yourself as a writer so I need to know: You are having a laugh. Aren’t you?

I wrote that because I was convinced that he was an accomplished writer who was taking the mickey out of all the half-literate posts we all come across. I didn’t see how it could be possible to get every single thing so reliably wrong (every apostrophe that should be there omitted; every apostrophe that should not be there included) unless you were doing it deliberately.

I received this reply: Hi John. I openly admit that I have not attended writing skills courses, or that my schooling was of any great standard, but I follow this by mentioning the importance of a proof reader. I have no doubt that your corrections are valid, and I thank you for taking the time to point them out. I may not be as ‘literate’ as many when writing my thoughts, but by the time those thoughts become a book the professionals have done their job well. It’s a team effort.

So what I’m asking is: Is this possible? If you lack the basic building blocks—the tools of the trade as I have called them—can proof readers and editors turn it into something saleable? Can it be done?

Comments would be welcome. Indeed, comments are sought. And I had better add that I did not (and would not have) publish this post until I had shown it to the blogger I mentioned and received his approval.

March 4, 2014

The reviews come slowly—but they come

Bit by bit, A Just and Upright Man gathers reviews. It seems that quite a lot of people have to buy the book for each one that reviews it. Somehow, that makes the reviews even sweeter when they come. This one turned up last week on Amazon’s UK site:

4.0 out of 5 stars Very enjoyable 23 Feb 2014

Format:Paperback

Superbly written historical fiction with plenty of suspense and tension to keep you turning the page. I am not familiar with the period in history but had the distinct impression that it was an accurate portrayal of the times. Will be looking for more books from the author RJ Lynch.

“Superbly written”. I like that—who wouldn’t? Another four star review had appeared on the UK Amazon site a few days earlier:

4.0 out of 5 stars Intriguing and Educational 20 Feb 2014

By Kirstie

Format:Paperback

‘A Just and Upright Man’ educated me enchantingly about the culture and practices of the late 18th century, in words I could understand. I wasn’t sure that I grew to know all the characters fully, but it was certainly clear that many of them, including the protagonist had light and dark sides, which left me curious to read more.

I was fascinated by the difference between now and then in how people communicated. If Blakiston needed to ask someone a question, there were no telephones, Facebook or Twitter, and it was not always practical or possible to visit someone or somewhere to simply ask questions. Communications were face to face, by third party word of mouth or in writing, so that geography and transportation mattered, and a single communication became an event or the day’s activity. This, and the story being set against a backdrop of political tensions over change to come and the early challenges to class and gender inequalities, characterized the period very clearly for me.

I experienced the odd unexpected shift from a safe to shocking scene, but suspect that these leaps were carefully designed to depict the harshness of certain aspects of the culture. Dark fears also lurked towards the end of the story, with an 18th century curse threatening to reach its clingy fingers out into Blakiston’s future. This worries me still, but I shall have to wait…

That’s a total now of four reviews in the UK, all of them good, and there are three on Amazon’s US site. I’m glad to have them, even though given the total sales of the book seven reviews since October doesn’t seem a heck of a lot. People like it, though, and they say they’re looking forward to the next in the series. That is so satisfying.

February 7, 2014

“Historical crime fiction at its very best”

This is some review from Book Viral for A Just and Upright Man

It is 1763. James Blakiston, overseer of Lord Ravenshead’s estate and a newcomer to the Durham parish of Ryton, is determined to solve the mystery of old Reuben Cooper’s murder – but he has no idea how to go about it.

Compelling historical drama unfolds in A Just And Upright Man by author RJ Lynch, as he commendably peels back the veneer of Georgian society to deliver an uncompromising tale of murder and mystery. Admirably eschewing the more popularly toted incarnations of the period, in favour of an altogether darker and more damning exploration of time and place, Lynch brings distinct flair to his enthralling tale with a meticulous eye for detail that is ever present. It is evident in the intricacy of his plot, but never more so than the verve with which he imbues his characters. Capturing humour and dark intent with turn of phrase that colours his telling in vivid detail; elevating this tale of detection and the dictates of a blinkered society to a class of its own.

Uncommonly authentic, highly engaging, A Just And Upright Man is historical crime fiction at its very best and rightly raises high expectations for future novels in the series. A credit to R J Lynch and recommended without reservation.

January 26, 2014

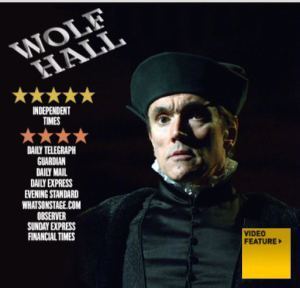

Wolf Hall at the RSC

It’s out of this world. Sublime. Possibly the best thing I’ve seen at Stratford in nearly 50 years of going there. The Swan Theatre is smaller than the new RSC main theatre and more intimate; we had seats in the very front row at the corner of the apron stage and while I’m not sure I’d want to sit there every time it gave us an excellent feel for the production. Cromwell and Henry VIII are brilliantly played but there wasn’t a single dud performance and the adaptation is wonderful. Don’t know how it will play out on a cinema screen but it’s beautifully tailored for that theatre. Good meal in the RoofTop Restaurant before curtain up, too.

http://www.rsc.org.uk/whats-on/wolf-hall/