Adam Fenner's Blog, page 3

May 4, 2025

Declassified Edition – Rerelease

Declassified Edition: O.P. #7 is Now Available for Free

Time is finite, and I try to treat it with respect. For the past month, most of mine has gone toward reviving the series The Horrors of War. I’ve updated O.P. #7, giving the my characters the attention they deserved but also leaving plenty of room to grow.

O.P. #7 (Declassified Edition) is now live. It’s free to download and read—no strings, no mailing list, just the work. You can get it here:

Download O.P. #7 (Declassified Edition) – EPUB, MOBI, PDF

Download O.P. #7 (Declassified Edition) – EPUB, MOBI, PDF

It is also available for print on Amazon, and there are some sites that it is available for purchase electronically, but don’t feel obligated. This story was always meant to be shared.

A Quick Update on Objective 2

Objective 2—the second book in The Horrors of War series—is being formatted for final printing. It picks up where O.P. #7 leaves off, and the scale expands: more danger, deeper fractures, and the quiet dread of realizing it can always get worse. It’s darker, stranger, and (I hope) as entertertaining.

Looking Ahead

This series is not just about war—it’s about fear, trauma, and the bond between people when nothing else holds. It’s personal, even when the horrors get big. And now that the first piece is out, I’ll be turning my focus to bringing the rest forward.

Thanks for reading, and as always, thank you for your time.

Photo by JOHN TOWNER on Unsplash

April 5, 2025

Hues of Hope – Reviewed

Review

Balroop Singh’s Hues of Hope is a poetry collection that moves between nature, personal

reflection, and the quiet strength that hope provides. Each poem in the collection carries the

weight of experience and emotion, yet there is always a sense of looking forward, a refusal to be

consumed by darkness. This poetry does not ignore struggle but instead uses it as a path toward

understanding and resilience. The themes of nature, self-discovery, and perseverance are woven

throughout, making them both profoundly personal and universally relatable.

Many poems reflect on inner conflict, grief, and personal transformation. Pain – My Antidote

shows how pain, though persistent, can become a teacher rather than a burden. “You were my

constant companion, / Now I have befriended you,” the speaker declares, shifting the dynamic

from suffering to acceptance. The poem does not just sit with pain—it pushes through it,

emerging with the realization that it “cannot even touch my soul.” This is a common thread

throughout the collection: hardship is acknowledged, but it is never the end of the story.

Nature plays a decisive role in shaping the emotional landscape of these poems. Stuck at Sunset

takes a simple, everyday experience—being caught in traffic—and transforms it into something

almost celestial. “Golden glare / Evoking vibes of celestial love” turns an ordinary moment into

something awe-inspiring, reminding the reader that even stillness has meaning. Be Your Own

Light takes a different approach, using nature’s coldness and colorlessness as a metaphor for

emotional struggle, yet the message remains the same—there is always a way to push back

against the gloom. “Wear the colors of your heart,” the speaker advises, reinforcing that hope is

something we create for ourselves.

Personal reflection is another defining feature of Hues of Hope. My Intuition is a poem about

self-awareness and the ability to see through pretense. “Your illusionary world / Comes alive in

my intuitive mind,” the poet writes, emphasizing a deep sense of knowing. The poem does not

just talk about intuition—it embodies it, revealing an understanding of human nature that is both

sharp and unwavering. This self-assurance carries into My Muse, where the speaker’s creative

force refuses to be limited by expectations. “I can’t be shackled / I dwell in the wondrous

woods,” they say, asserting that inspiration and expression cannot be controlled or contained.

Hope is the undercurrent that runs through the entire collection. Even when grief and loss are at

the forefront, as in Despondency, there is an openness to healing. “I want to return to love and

laughter,” the speaker admits, even while questioning whether pain will allow it. There is no

immediate resolution, but the willingness to ask the question already hints at the answer. This

same resilience is seen in Awakening, where a moment of realization transforms despair into

renewal. “Life is more than dwelling in sorrow / Let it flow with finesse,” the poem concludes,

shifting from emotional chaos to a quiet understanding.

The most potent example of this balance between personal reflection and universal hope is found

in Ode to Poetry. Poetry is a source of light, a mentor, and a means of making sense of the world.

“You absorb all my woes,” the speaker says, showing how words can carry pain and transform it. The relationship with poetry is not passive—it is an active force that guides and inspires. This

echoes the core of Hues of Hope: finding something to hold onto, even in difficult times.

Balroop Singh’s poetry is not about offering easy solutions. It acknowledges grief, struggle, and

uncertainty but never lingers in despair. Instead, it finds strength in introspection, nature, and

hope’s quiet but steady presence. The collection feels deeply personal, yet it speaks to something

more significant. There is comfort in these poems, not because they deny hardship but because

they show a way through it.

You may find more about Balroop Singha her website here.

Hues of Hope is available for purchase on Amazon here.

I had a tremendously fun time reading through and reviewing this collection. If you have a collection, whether newly published or a bit older I’d happily share my thoughts. It is a very simple process, I review a PDF copy of your work, free of charge. It takes me a few weeks, then I post my review on my blog, Goodreads and Amazon. If you are interested, feel free to contact me.

April 1, 2025

Shifting Priorities – Announcement

Time is our most valuable resource, and as I’ve gotten older, I’ve learned to treat it that way. Wherever I work and whatever I work on, I try to use my time wisely. My focus has shifted over the years—whether that’s a strength or a flaw, I may never know. Singular focus for decades can produce incredible work, but I’ve always meandered from topic to topic. It keeps my interest alive and gives me breadth, though perhaps at the expense of depth.

For the past year, my focus has been on poetry. Since late October, I’ve been reading and analyzing it—not just to deepen my understanding but also to build relationships within the community. I feel I’ve accomplished that, at least in a modest way. Now, I have two announcements to share.

1. Launching the War Poetry CollectionThis passion project has been in the works for quite a while. I’ve noticed that war poetry often goes overlooked. It’s a niche subject, and that’s understandable—soldiers have always occupied a small corner of society, even more so now as war becomes increasingly distant for many. I also believe that literary critics often fail to grasp its nuance in a meaningful way.

The War Poetry Collection, launching today, is my effort to gather and share poetry that focuses on war. While WWI makes up the bulk of the collection, I’ll continue expanding it over time. This will be a living, evolving project—one I’ll tend to as I discover new works, as they are introduced to me, or simply when I need a distraction. It’s my way of giving back.

2. Shifting Focus to Narrative WorkThis is where the real work begins. My next major focus will be on my narrative writing. I have a three-book collection that I plan to edit and release. Beyond that, a low-fantasy series has been taking shape in my mind, but bringing it to life will require deep research.

To do it justice, I need to develop a solid understanding of 12th-century European life and politics. Researching this era will take time, but it’s necessary. One of the things I admire most about authors like George R.R. Martin and Andrzej Sapkowski is their ability to weave rich historical details into their worlds. That level of depth comes from rigorous research—and now it’s my turn to put in the work.

What This Means Moving ForwardWith these shifts, I’ll be posting less frequently and engaging less in daily interactions. My writing time is limited—an hour or two each day at best—so I need to use it wisely. However, I’ll still be here, sharing from the War Poetry Collection and reading others’ work, just not as regularly as before.

I truly appreciate everyone’s patience and support. Thank you for being part of this journey with me.

Photo by Matthijs van Schuppen on Unsplash

March 31, 2025

A wee dram – Reviewed

Ah whisky, shall I have a little dram?

Beautifully mellow – amber, tangerine, and maybe musk

Come with me – it’s a journey

Deep into the highlands

Every step you’ll take

Fading in the mist

Granite unmoved

Hiding in full view

…

You may find the rest of the poem here.

A wee dram

© by owner. provided at no charge for educational purposes

Analysis

This poem is about more than just whisky. It is about time, tradition, and the connection between a drink and the land it comes from. The speaker does not just describe the taste of whisky but invites the reader on a journey through the Scottish Highlands and the Isle of Skye. As the whisky is sipped, the evening fades into night, and then, almost without notice, night turns into morning. The passage of time is quiet and seamless, like the way whisky settles in the glass, lingers on the tongue, and fades slowly. The poem does not dwell on the transition—it just happens, much like life itself.

The opening question, “Ah whisky, shall I have a little dram?” is casual but ritualistic. It feels like something familiar, something done before and likely to be done again. The whisky is described not just by flavor but by color and sensation—“amber, tangerine, and maybe musk.” These details make it feel warm and rich, something that extends beyond taste into memory and atmosphere. Then the speaker invites the reader to join them—“Come with me – it’s a journey.” From here, the whisky is no longer just a drink; it becomes a passage into something bigger.

The poem moves into the Highlands, a place that feels both open and mysterious. The mist fades, but the granite remains unmoved. The landscape is steady, unchanged, while everything else shifts around it. The sense of time passing in the poem is subtle, just as the scenery itself is both distant and present. The Highlands are not just a backdrop; they are part of the experience, just as the whisky is part of the land it comes from. The poem does not separate these things—it blends them together, making whisky feel like a product of history and place rather than just something to drink.

The Isle of Skye brings a shift in tone. The speaker encourages openness—“Just be… spread your wings.” This part of the poem is lighter, more expansive. The kites wheeling in the mountains and the reminder to “just breathe” create a sense of calm, a moment of stillness in the midst of movement. It is as if the whisky has carried the speaker into a different mindset, one of reflection rather than action. There is no rush, no need for urgency—just appreciation of the moment.

The final lines bring everything back to whisky. “Six o’clock is here / Talisker awaits.” This could mean early evening, the start of another night, or it could mean morning, a return to tradition, a continuation rather than an end. Talisker, made on the Isle of Skye, is known for its smoky, maritime character, tying the whisky back to the landscape described earlier. This final mention reinforces the idea that whisky is more than a drink—it is a connection to a place, a moment, and a way of life.

The poem does not try to explain or analyze. It simply moves, the way time moves, the way whisky lingers and fades. It captures a quiet experience—one that is not just about drinking but about being present, appreciating the details, and letting things unfold naturally. It does not rush or force meaning. It just exists, like a dram of whisky, waiting to be savored.

Photo by Dylan de Jonge on Unsplash

March 30, 2025

Mending My Own Light – Reviewed

Brenda Marie

Mending my own light, a quiet task,

A gentle hand beneath the mask.

Where cracks once lay and shadows fell,

I gather pieces I know so well.

The fire flickers, soft and slow,

A spark of truth begins to glow.

Each shard of fear, each tangle of doubt,

I mend with care, I work them out.

…

You may find the rest of the poem here.

Poem: Mending My Own Light

© by owner. provided at no charge for educational purposes

Analysis

This poem is about healing and rebuilding, not by erasing pain but by turning it into something meaningful. The speaker describes the process of putting themselves back together, not as a way to return to who they were, but as a way to grow into something even stronger. The imagery of cracks, shadows, and shards of fear suggests past pain, but the speaker does not treat these as things to be erased. Instead, they are gathered, stitched together, and transformed. The idea that struggle is necessary for real change is central to the poem. The line “The storms I’ve weathered, the tears I’ve known, / Are the soil from which my light has grown” compares emotional hardship to the way plants grow from the earth. Storms, which seem destructive, actually nourish the ground, clear away the weak, and create space for stronger roots to take hold. The poem suggests that personal struggles do the same—they lay the foundation for resilience.

The structure of the poem reflects this gradual process of healing. It begins with quiet, careful movements—the speaker gathers the pieces, mends them, and tends to their fire with patience. The rhythm is steady, and the short lines create a sense of deliberate effort. As the poem moves forward, the language shifts. Words like “bold” and “fierce” appear, showing that the speaker is growing in confidence. By the final stanza, the tone is no longer cautious but strong. The repetition of “reborn” emphasizes transformation. The speaker has not just repaired themselves—they have become something new.

One of the most powerful images in the poem is the idea of stitching wounds with gold “I stitch the dark with threads of gold.” This could be compared to Kintsugi, the Japanese art of repairing broken pottery with gold lacquer, which highlights the cracks rather than hiding them. The idea behind Kintsugi is that breakage is part of an object’s history, and repairing it in a way that makes it more beautiful adds to its value. The poem takes this idea and applies it to personal healing. The speaker does not try to erase their past pain but instead weaves it into their strength. Their wounds become part of their light, just as the gold-filled cracks in Kintsugi become part of the beauty of the repaired piece.

Fire is another important symbol in the poem. It flickers softly at first, delicate and uncertain, but as the speaker works through their pain, it becomes something steady and unbreakable. Fire can be destructive, but it can also be a force of renewal. In nature, wildfires clear away dead growth, making room for new life. The speaker’s fire does something similar—it transforms rather than destroys. The line “a fire that’s mine, forever alight” suggests that this strength is not temporary. It is something lasting, something fully owned by the speaker.

The tone of the poem is hopeful, but it does not ignore struggle. It acknowledges pain without letting it take over. The speaker does not dwell on what broke them; instead, they focus on the process of mending. The way healing is portrayed is realistic. It is not about pretending the past never happened, and it is not about waiting for someone else to fix things. The speaker takes an active role in their own recovery. The process is slow, requiring patience and care, but in the end, it leads to something even stronger than what was there before.

The poem’s message is clear—healing is not about going back to the way things were. It is about taking what was broken and turning it into something new. The storm that once seemed destructive becomes the soil for new growth. The cracks that once seemed like flaws are stitched with gold. The fire that once flickered uncertainly now burns steady and strong. The speaker does not just recover; they transform. The poem captures the idea that struggle is not just something to endure—it is something that can shape a person into something even brighter.

Photo by Markus Spiske on Unsplash

March 29, 2025

The Rainbow Moon – Reviewed

Cindy Georgakas

The rainbow moon called me tonight,

shimmering its prisms beckoning me to pay a visit.

I circled round and round until

I got the perfect shot.

It hovered right over the very place we blessed you

as your spirit took its place in the heavens.

I swear it happened like this.

You know me, I see through rose colored glasses,

but I’m not one for lacing or psychedelics.

You may find the rest of the poem here.

THE RAINBOW MOON PUBLISHED ON SPILLWORDS PRESS

© by owner. provided at no charge for educational purposes

Analysis

This poem is about memory, loss, and the way signs can appear in unexpected moments. The speaker sees a “rainbow moon” and feels drawn to it, moving around to take the perfect picture. But the moment is more than just a beautiful sight. The moon appears over the exact place where they said goodbye to someone they lost. This makes the experience feel meaningful, like a sign. As the speaker tries to take a picture, butterflies appear, and they connect them to the person they lost. The butterflies become symbols of the spirit world, moving between life and death, carrying a message that their loved one is safe.

The poem follows the speaker’s thoughts as they take a picture, notice strange details, and feel a presence around them. The moon and the butterflies become symbols of the person who has passed, and the speaker interprets them as proof that their spirit is still near. The poem explores the idea that those who have left us may still find ways to communicate, even in small, fleeting moments. The speaker does not question whether this is real or imagined; they simply describe it as it happened.

The structure reflects how memories and emotions appear in waves. The lines are short, sometimes broken up in ways that feel like pauses in thought, as if the speaker is processing everything in real time. It is written in free verse, without a strict rhyme or rhythm, making it feel natural, like a memory unfolding. The first lines set up the scene—the rainbow moon appears, and the speaker moves around, trying to take the perfect picture.

The butterfly plays an important role in the poem. It is not just an insect in the night sky; it becomes a messenger between two worlds. The speaker calls it a “rainbow butterfly” and an “ethereal being of light,” suggesting that they see it as more than a coincidence. In many cultures, butterflies are symbols of the soul, believed to carry messages from those who have passed. The poem plays with this idea. The butterfly appears at the right time, right when the speaker is trying to capture a moment of remembrance. It is fleeting, impossible to hold onto, just like the person they lost. But even if it does not stay, its presence is enough to bring comfort.

The camera is another key part of the poem. The speaker is trying to take a picture, to hold onto the moment, but the camera does not capture what they see. They say, “While my camera deceived me, your colors fluttered bright.” This suggests that some things cannot be recorded or proven, but that does not mean they are not real. The speaker trusts their own experience over what the camera shows. The camera’s failure becomes part of the poem’s message—some things are only meant to be felt, not documented.

The tone of the poem is both sad and hopeful. The speaker is mourning, but they also feel reassured. They see signs that their loved one is still with them in some way, and instead of doubting, they accept it. The phrase “I swear it happened like this” shows both confidence and a need to affirm the experience. They know how it might sound to others, but they stand by what they saw. The final action—calling the mother—adds another layer of meaning. This moment is not just for the speaker; it is something that needs to be shared.

The poem also plays with the idea of perception. The speaker mentions seeing “through rose-colored glasses,” which suggests that they are aware they see things in an emotional or idealized way. But they also push back against doubt by saying they are “not one for lacing or psychedelics.” They know what they saw, and they believe it. The contrast between what the camera shows and what they feel reinforces this idea—just because something cannot be measured or recorded does not mean it is not real.

Overall, the poem is about a moment that cannot be fully explained or captured. The speaker experiences something powerful, but their camera does not reflect it. Instead of questioning themselves, they believe in what they saw. The poem explores the ways in which memory and emotion shape perception, and how people find comfort in signs from beyond. It does not try to argue whether these moments are real in an objective sense; it simply presents the experience as it was felt. The speaker’s loss is clear, but so is their connection to the person they are missing. The poem is about seeing beyond what a camera can capture and trusting what the heart knows to be true.

Photo by Joshua J. Cotten on Unsplash

March 28, 2025

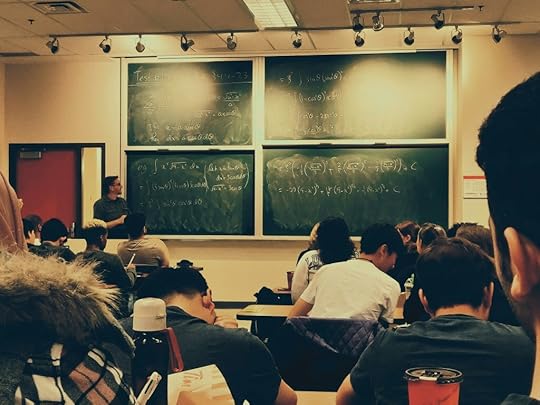

Calculus: The Great Betrayal – Reviewed

Oh, Calculus, you gave me pain,

Derivatives fried my poor brain.

Integrals made me want to cry,

Yet here I stand—please tell me why?

You swore you’d help me every day,

In useful, math-y, grown-up ways.

But in the end, amidst my strife,

I’ve never once derived my life!

…

You may find the rest of the poem here.

Calculus! …a poem

© by owner. provided at no charge for educational purposes

Analysis

This poem is about more than just frustration with calculus. It is about the gap between what is taught in school and what is actually useful in daily life. The speaker describes their struggle with derivatives and integrals, but the frustration is not just about difficulty. It is about effort that led to nothing. They expected calculus to be valuable, something that would come in handy as an adult. Instead, they find that all those complex ideas serve no purpose outside the classroom. The speaker is looking at the education system and questioning why students are required to learn things they will never need.

The humor makes the message stronger. The rhyme scheme gives it a light, almost sing-song quality, even though the frustration is real. The first part sets up the idea that calculus was painful to learn, but instead of just ending there, the poem shifts into something bigger. The speaker expected calculus to be useful, but instead, they have gone through life without ever needing it. Then the poem lists examples of common situations—shopping, cleaning, tipping—all things that require some math but not calculus. These examples exaggerate the point, but that is what makes it clear. If calculus is as important as students are told, why does it never come up in real life? The final stanza directly calls out Newton, joking that unless someone is building a spaceship, calculus does not seem to serve much purpose.

The poem raises a bigger question—what should people actually be learning? The speaker does not suggest that math should be ignored, just that it should be more practical. Instead of calculus, maybe students should spend more time learning how to manage money, budget for groceries, or understand taxes. The examples in the poem make this argument without stating it directly. When the speaker talks about grocery shopping and cleaning, they are pointing out that these are the kinds of skills people use all the time. The poem suggests that education should focus more on what will actually be helpful in everyday life.

The poem plays with the idea of expectation versus reality. The speaker expected calculus to be practical, something that would help them as an adult. Instead, they find that all the formulas and concepts they struggled with have no clear purpose in their daily routine. The disappointment comes from realizing that they spent time and effort on something that, in the end, does not seem to matter. The humor makes the frustration easier to digest, but it also makes the argument stronger. If calculus is only useful in rare, highly technical situations, then why is it taught as an essential skill?

The poem is funny, but it has a serious point. It questions why students are expected to spend time and effort on subjects that do not have clear, practical value. The rhyme scheme and casual language make it entertaining, but the message is something many people can relate to. The poem does not suggest a solution, but it does highlight a frustration that a lot of people feel—that education often focuses on things that are not useful while skipping over things that would actually help in daily life. The speaker might be exaggerating, but the argument is one that resonates, making the poem both humorous and thought-provoking.

Photo by Shubham Sharan on Unsplash

March 27, 2025

Waiting for It – Reviewed

threadfollower

I overheard a gentle comment

while I waited for the next part

of my life to begin:

“Sometimes it is in the waiting.”

My expectation increased as I hoped

for an explanation of “it.” There was none.

…

You may find the rest of the poem here.

Waiting for It

© by owner. provided at no charge for educational purposes

Analysis

This poem is about waiting, but not just the act of waiting—the uncertainty that comes with it. The speaker is in between moments, expecting the next part of life to begin, but they do not know what that means. They hear someone say, “Sometimes it is in the waiting,” a comment that suggests there is meaning in this in-between space. But the statement does not explain what “it” is, and that lack of clarity creates tension. The speaker wants to know what they are waiting for. They start guessing—maybe it is a better life, love, or some kind of deeper happiness. But instead of feeling reassured, they begin to worry. If they do not know what “it” is, how will they know if they have found it? And what if they are waiting for it the wrong way?

The poem does not try to answer these questions. It does not define “it” or say whether the speaker’s concerns are valid. That is what makes the poem unsettling. The speaker is left to decide for themselves, and that is the real challenge. The poem highlights a common experience—people wait for change, assume that something new is coming, but rarely know what to expect. They look for meaning outside themselves, hoping for direction, but often have to define it on their own. The poem captures the weight of that responsibility. It starts with quiet observation, shifts into hopeful anticipation, then moves into fear. The longer the speaker sits with their uncertainty, the more anxious they become. If they cannot name what they are waiting for, how can they be sure they are waiting correctly?

The structure of the poem follows the speaker’s thoughts. It begins with an overheard comment, something passive, then shifts into an active search for meaning. The speaker moves through possibilities, listing ideas, trying to pin down what they are waiting for. But instead of landing on an answer, the thinking spirals. The final question changes the focus from the unknown future to the speaker’s own actions—what if they are not waiting the right way? The poem does not offer reassurance. It just stops, leaving the speaker in doubt.

The tone follows this same shift. It starts out neutral, almost reflective, but as the poem progresses, the uncertainty builds. The phrase “My expectation increased” suggests excitement, as if something is about to be revealed. But that feeling is quickly replaced by doubt. The lack of explanation changes the mood. The more the speaker thinks about “it,” the less certain they feel. The final shift to fear happens quickly, but it is not dramatic. The poem does not use emotional language or exaggerated imagery. The simplicity makes the shift feel natural, like someone realizing mid-thought that they might have made a mistake. The waiting is no longer just a pause before something new. It becomes stressful.

The simplicity of the poem makes it feel personal. There are no complicated metaphors or decorative language. The thoughts unfold naturally, as if the speaker is thinking through them in real time. This makes the transition from hope to fear feel more immediate. The poem does not try to resolve the speaker’s doubt, and that lack of resolution is what makes it effective. It leaves the speaker, and the reader, stuck in that same uncertainty. It suggests that the act of waiting is not just about patience but about defining what is worth waiting for in the first place.

Photo by Meritt Thomas on Unsplash

March 26, 2025

No 不 – Reviewed

In a society with no

Boundaries, saying no

在一個不分界線的

社會,說不似乎

…

You may find the rest of the poem here.

No 不

© by owner. provided at no charge for educational purposes

Analysis

This poem is short, but it sets up a big idea. It talks about boundaries and how saying “no” is not just a choice but something necessary. In a world where limits do not exist, refusal becomes the only way to create them. The poem treats “no” as something practical, not emotional. It is not about personal feelings but about weighing benefits, making calculations. Decision-making becomes almost mechanical—if the total gain is greater than personal goals, then saying “yes” makes sense. If not, then “no” is the logical response.

The structure is simple. Each line moves directly into the next, forming a continuous thought. The lack of punctuation at the end of the lines makes it flow without pause, reinforcing the idea that this is not about personal reflection but about stating a principle. The way it is written makes it feel more like a rule than an observation. There is no questioning or hesitation—just a direct statement of how things work in this kind of society. This also makes the poem feel impersonal. The speaker does not position themselves within the idea. They do not argue for or against it. They simply describe it, which makes it feel more like a fact than an opinion.

The tone is neutral, almost detached. There is no frustration, no emotion, no argument. It does not say whether this way of thinking is good or bad. It just presents it. That detachment makes the poem unsettling. It presents society as something without real boundaries, where people have to constantly negotiate their own limits. Saying “no” is not about preference but necessity. There is no talk of personal freedom or morality—only calculations of benefits and goals. This approach makes the world of the poem feel rigid. It suggests that people are not making decisions based on what they want but based on what is required to function in a society that does not offer clear limits.

The last lines introduce an exception: “unless the total benefits of acceding outweighs personal goals.” This makes the whole poem conditional. It is not saying that refusal is always necessary—only when saying “yes” does not bring enough gain. This turns decisions into transactions. It is not about what a person wants but about what makes the most sense in a system where limits do not exist. The idea of benefits being weighed against goals makes it clear that choices are not about individual desires. They are about what is most efficient. This suggests that in a world without boundaries, people are forced to constantly measure their responses, making sure they do not lose themselves to external demands.

The poem does not take a strong stance, but it raises a question: if refusal is a requirement, then is agreement ever really a choice? It suggests that personal goals are always weighed against external expectations, that decisions are not about what someone wants but what makes the most sense based on outside factors. It makes saying “no” feel less like a boundary and more like an obligation, something forced rather than chosen. The simplicity of the language and structure reinforces that idea—there is no emotion, no argument, just a statement of how things work. The poem is short, but it leaves an uneasy feeling, as if personal choice is just an illusion.

Photo by Linus Nylund on Unsplash

March 25, 2025

UNIVERSAL TRUTH – Reviewed

Probable cause defeats purpose

the empty cache augments

strike the keyboard release some tension

fumble around perfunctory practice

type the unfortunate turn of events

scramble the code traverse the gradient

update the debatable save unstable changes

decrypt the classified sharpen the tool

…

You may find the rest of the poem here.

UNIVERSAL TRUTH

© by owner. provided at no charge for educational purposes

Analysis

This poem moves through different ways of communication, shifting between written words, spoken language, natural signs, and supernatural messages. There is no clear narrative, but there is movement—thoughts being typed, voices being lost, nature signaling change, ghosts leaving messages. Communication is not stable. It is distorted, interrupted, and erased. Meaning is unclear, but that seems intentional. Instead of giving direct answers, the poem shows the struggle of making sense of fragmented information.

It starts with contradictions. “Probable cause defeats purpose / the empty cache augments.” These lines suggest a breakdown in logical thinking. An “empty cache” brings up the idea of stored but erased information, like a computer remembering what has been deleted. This ties into written communication—words are typed, saved, changed, and lost. The poem treats writing like a process of trial and error, where words are not fixed but constantly shifting. This reflects how language works—people speak, revise, rephrase. Meaning is never final.

But writing is only one way of communication. “Babel’s voice scattered sound” references the biblical Tower of Babel, where language fractured, making understanding impossible. Scattered voices suggest speech that is lost, confused, or broken apart. “Crash heartbeat’s unreliable rhythm” ties spoken language to the body’s rhythm, but here, even that is unsteady. The poem suggests that spoken words, like written ones, do not always hold steady. They can be misunderstood, interrupted, distorted.

Then, there is nature. “Swollen rivers invite destiny / somnambulance ice and snow.” These lines move away from human-made language to natural signs. Rivers rise, ice forms, snow falls—these are all signals of change. Unlike writing or speech, natural communication happens on its own, without human control. A swollen river means a flood is coming. Snow signals stillness. The poem does not explain these images, but they act as another kind of language, one that exists without words.

The poem also brings in the supernatural. “Holy ghosts’ inevitable crime.” Ghosts exist between presence and absence, like forgotten words. Their “crime” might be that they cannot be ignored, or that they linger without speaking clearly. Supernatural communication is often indirect—signs, strange sensations, an unexplained feeling. The poem treats this as just another way meaning is created, alongside typing on a keyboard, voices breaking apart, and nature giving quiet warnings.

The last lines bring everything together. “Trample banal delete explanation.” The poem refuses to be simplified. “Deplete the poem the unsolvable problem.” If communication is unstable, poetry is even more so. “Nature’s metamorphosis universal truth.” Truth, like nature, is always changing. Like spoken words, it is lost and misheard. Like writing, it is revised. Like ghostly messages, it is uncertain.

The poem captures the instability of language. It mixes digital, spoken, natural, and supernatural communication, showing how all of them can fail or shift. The short lines, the lack of punctuation, and the clipped phrases create urgency and fragmentation, mirroring the way meaning is built and broken. Instead of offering answers, the poem shows the process of trying to understand, of wrestling with words that refuse to be pinned down. It embraces poetry’s complexity—the way meaning is layered, fractured, and always in motion.