R.J. Heller's Blog: Life Downeast, page 2

April 16, 2023

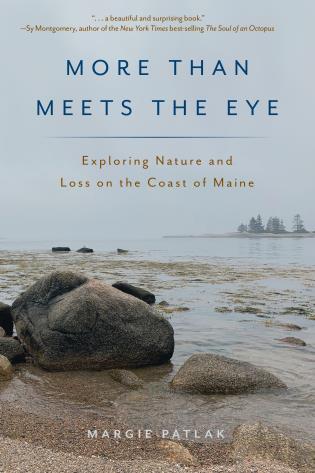

More Than Meets The Eye: Exploring Nature and Loss on the Coast of Maine

“The question is not what you look at, but what you see.” — Henry David Thoreau

*******

This new collection of essays touches personal loss in a unique way. Rather than deal with it by only embracing the past through personal memories, both tenses —past and present— are equals in the effort to make sense of it all. Add to it a natural world that perpetually surrounds life, loss becomes tolerable, understandable and perhaps even beautiful.

To do this author Margie Patlak in her new book, More Than Meets the Eye, says one must let their sense of wonder look into the soul of a place, allow its flora, fauna and of course the sea to open up, letting us truly see and, in return, heal.

To do this author Margie Patlak in her new book, More Than Meets the Eye, says one must let their sense of wonder look into the soul of a place, allow its flora, fauna and of course the sea to open up, letting us truly see and, in return, heal.

The award-winning writer takes us on her journey of seeing the natural world on the coast of Maine as she deals with personal loss. She does this through her meticulous layered and artful approach that is her writing and sprinkles it with golden nuggets of wonder both from a science-based perspective and a very real human perspective.

An accomplished science writer, Patlak has written hundreds of articles about the environment, neuroscience, biomedical research and technology for publications such as the Washington Post, Discover magazine, the Philadelphia Inquirer and many others. Patlak has degrees in botany and environmental studies and shares time living in Philadelphia and Corea, Maine

Patlak’s journey begins with “seals swimming out to meet my mother” as her remains are sprinkled into the Gulf of Maine. Two years later the ash remains of her brother would be left on a mountain in Vermont. It was then both Patlak and her husband Frank realized the brevity of life, so they purchased acreage in Maine and built a life there claiming it “as an emotional lifesaver.”

These essays explore nature and its offerings in good times and bad. From the metamorphosis of monarch butterflies, to the ethereal movement of fog, clouds and Maine’s unpredictable weather, to the monumental tectonic creep of mountains, to time itself kept in rhythm by the tides — all are captured in a science-based perspective that is done so effortlessly that I believe Patlak could be considered a naturalist poet.

Such as when she describes her shift from distasteful feelings about fog-laden days to “what treasures they offer.”

“When the mist hangs over the bay I mull over migrating butterflies, my need to name the birds or the vastness of the night sky; I remember my brother intently gazing at the woods from his wheelchair, my father giving me the gift of a beating heart and my mother moved by the rosy beauty of the sun sinking into the bay. What they signify becomes more palpable, substance gives rise to form and glistening pearls suddenly appear — out of the fog.”

In addition to the healing grace of nature, people, too, can meet the moment to make things better. In “People of the Peninsula” Patlak’s “wariness of friendly folk dropping by unannounced” eventually chips away at her Theoureavian expectations of life on a peninsula. It did for Thoreau, too. She notes that, during his time of solitude at Walden Pond, it’s rumored he often made trips to nearby Concord.

Here, too, on an unfamiliar peninsula it is the people who make the difference. Whether it’s a neighbor removing a downed tree from the driveway, others bringing food or just conversation, people will provide added comfort given any situation and as such should be celebrated just as much as the natural nirvana that is Maine.

“Dwelling in this rural community has made me see the better side of human nature, including my own, which, like the bent-over birch trees you see up here, has become more pliable, with branches that reach out and touch others. I also realize that all my lofty ideals fostered by nature memoirs I’ve read can carry me only so far when there are more pressing needs close to the ground that only the people near me can meet.”

In closing, Patlak brings us full circle with the playful movements of a new life. Though her brother and mother are not there to witness the buoyancy of a baby sitting in her highchair calling on the “adults in the room” to just take a moment to become this one, Patlak knows there is no end, just a continuance of what was yesterday and is today, like that of nature.

“The healing mascot for our family, Jo answers the ultimate question, Why is there decline and death followed by birth and life? That answer surfaces when I see her unblemished by experience, her eyes sparkling with excitement, her body pulsating with life’s heartbeat, her entire being ready to explore: To refresh the wonder.”

Life and loss amidst the surreal natural wonder that is coastal Maine are here in real-life moments that confirm the perpetuallity of life. It truly does not end if we open our self to the healing power of a place, its people and its natural wonders.

Nature indeed will speak to you about the nature of life.

Down East Books, 2021, softcover $19.95

© 2023 RJ Heller

First Published: The Quoddy Tides, March 24, 2023 : The Calais Advertiser, April 6, 2023: Bangor Daily News, April 9, 2023: Machias Valley News Observer, April 12, 2023

The post More Than Meets The Eye: Exploring Nature and Loss on the Coast of Maine appeared first on RJ Heller.

February 23, 2023

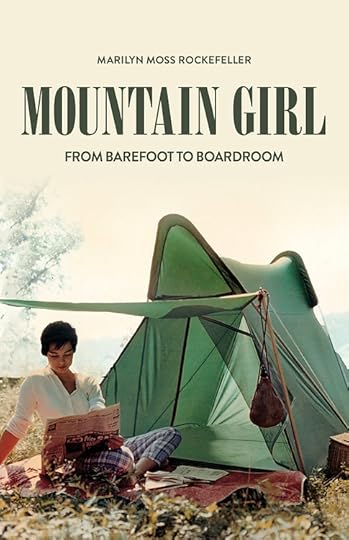

Mountain Girl: From Barefoot to Boardroom

What do we keep with us when everything around us is changing? In her story Mountain Girl, Marilyn Moss Rockefeller answers that nothing changes unless you allow it to, you are you and that is carried with you forever. This is the very thought I had as I closed this wonderful memoir.

Rockefeller is also the author of the award-winning book Bill Moss: Fabric Artist & Designer. Her essays have appeared in a number of publications. She cofounded Moss Tent Works with Bill Moss in 1975 and served as president and CEO of Moss, Inc. until 2001. She lives with her husband, James Rockefeller Jr., who published his own memoir in 2018, titled Wayfarer. They live in Camden.

Rockefeller is also the author of the award-winning book Bill Moss: Fabric Artist & Designer. Her essays have appeared in a number of publications. She cofounded Moss Tent Works with Bill Moss in 1975 and served as president and CEO of Moss, Inc. until 2001. She lives with her husband, James Rockefeller Jr., who published his own memoir in 2018, titled Wayfarer. They live in Camden.

In the book’s acknowledgement, after thanking those who helped with the book’s publication, Rockefeller leaves a “note” from writer to reader: “Further, I thank you, my reader, for giving this book a chance, with the hope that you will not only like it but find something that resonates for you here in these stories about facing our fears and daring to do that which most calls us.”

The sentiment is appropriate because within that note of thanks, the essence of this book — its purpose, the author’s intent — is held. We should all move through life with the strength of purpose and face our fears no matter the cost. Through vivid storytelling, this memoir about a woman who did just that is a testament that anything can be achieved.

This memoir was a surprise. Having known the Rockefeller name, I never knew about the artistry of Bill Moss, his designs, Moss Tent Works nor that the company was co-founded, built and eventually sold by a woman at a time when women in the corporate world were a rare sight. The grit and determination that seeps from every page carried me along on a sometimes “rough and tumble ride” softened often by quiet interludes of emotional storytelling.

Her story starts in the foothills of West Virginia. As a little girl, “MarilynRae” (her father adding the “Rae”) grows up on her grandparent’s farm in the Appalachia town of Elgood. Through her childhood years Rockefeller embraces an impoverished life by spending her days climbing trees, shooting squirrels for dinner and breaking the rules from time to time. It was a life also rich in the moments she shared with the people that came and went on the farm, including her mom and dad.

For her that farm was a world unto itself. As the years would pass Rockefeller would find herself returning, “to that small Appalachian farm in my mind and to the strength and sense of wholeness I had there.”

A life lesson she learned early on from her grandparents comes from a framed, hand-stitched aphorism that hung over the kitchen table: “Back then, at my young age, I’m not sure I knew what this saying really meant. But I now realize that my grandparents lived by these words. They were kind, giving people. Listeners instead of talkers. ‘Little behooves any of us, to find fault in the rest of us’ — a saying that I would also come to live by.”

Over time the tomboy grows up experiencing significant life events that Rockefeller adeptly tells in an almost short story-like fashion. Her words are like that of a paintbrush, often subtle, sometimes bold, like when her parents separate, and later when she is told her father had died.

After the death of her father, Rockefeller moves north and in a sense is transformed by her mother — an educator who gradually moved north over the years — from a “mountain girl” to a city girl. She attends high school in Connecticut, then moves to Michigan, attends college and meets designer Bill Moss. They marry and, with two children in tow, make their way to Maine, where the company Moss Tents is eventually born. Business struggles take their toll; a marriage ends; a business is saved then sold; and she meets and marries James “Pebble” Rockefeller.

It is an incredible journey of adventure, struggle, loss, love found, lost, then found again. Through it all Rockefeller maintains that sense of self she garnered back on her grandparent’s farm. It is a life saturated by experience and a must-read for anyone seeking a truly inspirational story.

As she closes out this memoir of a life “well-lived,” Rockefeller reflects back to when she began “writing it all down.” In doing so she realizes she had come full circle, moving away from finding herself through others to being herself. Over time she listened to her voice and did what her heart told her to do, without judging or finding fault in others, just like that stitched saying above the kitchen table.

“I saw myself then on the porch swing in Elgood — a little spirited, fearless MarilynRae. The mountain girl who always sought belonging had grown up. She now had her own courage and strength.” And as any good story will do, I, too, in the end found myself sharing that porch swing with MarilynRae as both a reader and now her friend.

Islandport Press, 2022, softcover, $18.95

© 2023 RJ Heller

First Published: The Quoddy Tides, January 27, 2023 : Machias Valley News Observer, February 15, 2023: Calais Advertiser, February 16, 2023: Bangor Daily News, February 20, 2023

The post Mountain Girl: From Barefoot to Boardroom appeared first on RJ Heller.

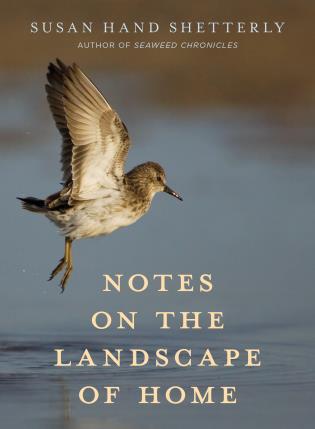

Notes on the Landscape of Home

Time. It is in everything. It holds onto everything and sometimes it folds in on itself allowing a much-needed pause in life. This was my first thought as I closed the book Notes on the Landscape of Home by Susan Hand Shetterly. It is an exceptional collection of essays from a writer undoubtedly grounded in both time and place.

Shetterly lives in Surry and is the author of Settled in the Wild and Seaweed Chronicles: A World at the Water’s Edge, as well as a number of children’s books including Shelterwood, named an Outstanding Trade Book for Children by the Children’s Book Council.

Shetterly lives in Surry and is the author of Settled in the Wild and Seaweed Chronicles: A World at the Water’s Edge, as well as a number of children’s books including Shelterwood, named an Outstanding Trade Book for Children by the Children’s Book Council.

For the reader, Shetterly offers clarity of place, both the place she calls home or any situation for that matter that affords her a quiet moment. When that happens — when both time and place come together — a pure reflective experience is captured, becoming a pure memory for her. Reading this book is like taking a journey to where everything touches the senses, making it both real and personal.

But it does not happen all the time. Time has a way of sometimes adding or distracting from a place. Yet Shetterly with her prose shares the essence of place no matter the circumstance. Whether good or bad, her experience is simply “to be” and to observe it all.

The 32 “notes” in this book cover a myriad of experiences. Shetterly is a keen observer. She sees all, or so it seems, and her writing guides us into her world. A world fraught by climate change, altered habitats, human cultures both worldly and here in Maine.

She shows us that if proper time is given, goodness will bubble to the surface, assuaging the uncertainties and often the dread that can easily overcome us at any time.

In “Time Alone,” Shetterly reflects on time as friend and foe — as a neighbor during the pandemic. She walks us through that time by reflecting on a Winslow Homer painting, ”The Artist’s Studio in an Afternoon Fog.” The oil painting, heavy in brown tones, dense black and silvery whites, lodged its place in her memory a long time ago. And when needed — like during a time of pandemic isolation — it creeps back in and meets the moment with its muted colors laid down by hands from “someone else’s” isolation.

“There is a difference between being told to stay home to stay safe and doing what Homer did in those years at the shore, which was to choose to turn away from the human world to see if he could make something that told the truth and would last. Living in a different sort of alone time now, it seems to me he did just that.”

In another essay the night sky is revealed as a shared constant in a forever-changing world. And like that hunter Orion who wanted to rid the world of the wild, Shetterly reminds in “Children of Orion,” that it is the wildness that must remain the one true constant — to be protected by all cost.

“We’re nourished by what’s left of wildness, by the knowledge that we belong among other species — both animal and plant — and to lose them would be to lose something we honor in ourselves. When the stars wake me upon especially clear cold winter nights — it’s their silence, I think, and their needle-sharp points of light that disturb my sleep — he’s there, the hunter who thought we’d be better off all by ourselves on this Earth.”

And in the whimsical essay, “A Sneeze,” Shetterly reflects on the importance of story —both the good and the bad — by way of E.B. White’s classic, Charlottes Web. For her, White’s book is “very close to a perfect book.” And even though death becomes real at the end of the story, it is significant in that it brings out the beauty of what real friendship can be and to be alive to share it.

“Death is steeped into its pages, as is life, immediate, brightly colorful and witty, playing itself out against the darker background. The counterpoint between the two gives White a chance to write some of his most moving prose about the beauty and joy of being alive.”

In the opening preface to her book, Shetterly shares a line from a T.S. Eliot poem that provides a clue as to how the magic happens if one pays close attention to all things on land, in water, community and the wildlife that wraps itself around it all.

“At the still point of the turning world …

there the dance is …”

The still point for Shetterly is this place called Maine —the small neighborhood in a small town where she lives — and the dance, she says, “is between the individual lives of the many species that live here, the community we make together, and time.”

This was a joyous read for me personally and professionally as a columnist living and working in Down East Maine. The personal observations amidst our mutual “friends” Shetterly invokes by way of Thoreau, White, Leopold, Homer and many others provided me a “still point” accompanied by a smile in this turning world.

Down East Books, 2022, hardbound, $22.95

© 2022 RJ Heller

First Published: The Quoddy Tides, November 25, 2022 : Machias Valley News Observer, December 14, 2022: Calais Advertiser, December 15, 2022: Bangor Daily News, December 16, 2022

The post Notes on the Landscape of Home appeared first on RJ Heller.

January 24, 2023

A Downeast life — Starboard

The 11 or so miles from town are a constant in a world that is forever changing. The drive in either direction is a mirror image of itself. It is a pure Downeast drive. Old houses dot the road’s periphery, piles of fishing gear camp out in yards, glimpses of water appear around almost every bend, wildlife of all types come and go marking their time in the tracks they leave behind. And still, the peace and tranquility that is this place remains a constant, too. That place is Starboard.

*******

Every Downeast town is special. And in every town there is that one person or persons who embody an essence that makes that place so special. They are a part of the community, yet the many others who live there believe that person or persons are the “soul” of that community. For anyone traveling from Machias down that 11-mile stretch of road known as Port Road you will eventually come to a slice of heaven known as Starboard.

It is a place that has captured time and stubbornly refuses to let it go. For many residents in or just outside Starboard, meaningful memories are plentiful: family picnics on the shoreline; generations connected in some way to its one-room schoolhouse; skipping stones in “the pond” when the tide was in; or as fishermen taking a break while taking in the serene calm that is the cove’s protected waters. Though change is all around us, a drive or a walk in Starboard still has that “old days” feeling amidst a natural beauty biding its time around every corner.

For those who have made that drive to Starboard, up until just a few short years ago they would have undoubtedly come across a husband and wife out for their daily walk. He, with his walking stick and a funny story loaded and ready; she with her hat on, arms up moving back and forth in sync with her steps.

For those who have made that drive to Starboard, up until just a few short years ago they would have undoubtedly come across a husband and wife out for their daily walk. He, with his walking stick and a funny story loaded and ready; she with her hat on, arms up moving back and forth in sync with her steps.

They were two peas in a pod. Their walks down the road were legendary. They did not walk far, yet it still took them a good while because of all the stops they would make on their travels. A stop to wave, extend a greeting to a passerby, a neighbor, a stranger even, it did not matter — their walks were a greeting to any and all in Starboard. And by the time the roadside visit with them was over, one almost felt like family.

Their home in the cove is simple. Perched on the shoreline the house points southeast, towards the islands Cross, Stone and Ingalls. The house has a clear view— no matter the sun’s seasonal juxtaposition — of that glorious Starboard sunrise. The beach out front harbors an old rowboat used to hand-haul traps from time to time and is where one, if quiet, will find his footsteps and hear her laughter from their days in a cove that welcomes everyone.

Photo by Vernon Sprague

Remnants of a small patch of ground where corn and other vegetables would be planted are still visible. That garden is now a thumbprint of their effort to take from the Earth only what they needed. In return they always remembered to give thanks for that bounty.

Just past their home at the end of the road —where macadam meets dirt— there is a one-room schoolhouse. Red in color, the schoolhouse is a relic from the Starboard past. It along with the old firehouse building next door is saturated in story. Floating like halos both inside and out are their laughter and their earnest desire to know how everybody is doing.

Just past their home at the end of the road —where macadam meets dirt— there is a one-room schoolhouse. Red in color, the schoolhouse is a relic from the Starboard past. It along with the old firehouse building next door is saturated in story. Floating like halos both inside and out are their laughter and their earnest desire to know how everybody is doing.

Vernon and Lois (Ingalls) Sprague were of this place. They lived on ancestral land that is part of that long-ago story. They were exceptional neighbors and dear friends. And even though they are gone, their spirit remains a steward of this place called Starboard, or as Lois would always say, “The Cove.”

They cared about this place, this community, and always looked for the good in people. Their laughter, the hugs, the stories Vern would not let you leave before hearing are still very much here. Their footsteps, like those of all living creatures in breath and substance, are still very much a part of this place and will always be because of who they were, who they still are.

Their essence and that of this place they called home is always present. It is held within the memories of family, friends and neighbors still living and working here; within that small single room that is still a schoolhouse; around a community club table pulling lobster meat from the shell; along the beaches and waters of this place that is held within our hearts eternal.

In today’s world it is easy to find fault with the past. Most of the country right now has a front row seat for finding fault with the past. Even here in Starboard it happens on occasion. The subtle and sometimes “not so” subtle complaints trickle up from the shoreline, the pond, along dirt roads spilling out into a community that mostly doesn’t listen because time is too precious. Here in Starboard most of us simply want to enjoy what we each have, share it with others, and love one another while doing so, just like Lois and Vernon did.

© 2023 RJ Heller

Published in The Quoddy Tides, January 13, 2023

The post A Downeast life — Starboard appeared first on RJ Heller.

January 23, 2023

That sense of wonder

“A child’s world is fresh and new and beautiful, full of wonder and excitement. It is our misfortune that for most of us that clear-eyed vision, that true instinct for what is beautiful and awe-inspiring, is dimmed and even lost before we reach adulthood.” — Rachel Carson

*******

I will always remember her eyes being wide-open whenever outside. No matter if walking a trail or along a coastline, she always brought along her child-like awe. Tide pools reflected her sense of wonder at the magic she saw. Her girlish laughter, her sheer enjoyment in seeing something for the first time made the experience truly memorable for us all.

A long time ago, on her first and only visit to Maine, my mother’s best friend Mary quite literally became a child again. Scampering across rocks, gazing into tide pools, her 50 something years retreated to a place we all experienced as children — that magical world of wonder.

A long time ago, on her first and only visit to Maine, my mother’s best friend Mary quite literally became a child again. Scampering across rocks, gazing into tide pools, her 50 something years retreated to a place we all experienced as children — that magical world of wonder.

When she saw something for the first time, Mary’s smile and joyous laughter came pouring out, ushering us all to gather around her, to see what she was seeing. During her visit, experiences like that — immense joy and serene quiet — took us to a better place if but for a moment.

By definition wonder is that feeling of surprise tinged with admiration brought on by something unexpected, unfamiliar. It is an inexplicable feeling we all had as children, a wonderful feeling unfiltered and without guardrails. Wonder is that desire to be, to be curious and to know something, But to know what? We only know that when we experience wonder.

In remembering Mary’s visit to Maine, she was the noun and verb form of wonder incarnate. By her presence — with her unabashed amazement at these Maine moments — our experience was made better. Mary helped show us the wonder of this place.

The marine biologist and conservationist Rachel Carson spent many summers in Maine writing and sharing time with family and friends. In The Sense of Wonder, which began as a well-received essay in the years prior to the publication of Silent Spring, Carson captured many of these Maine moments. She continued expanding it throughout the years. It was to be her last book, published posthumously in 1965.

In The Sense of Wonder, Carson’s focus is on the time she spent at her Maine home with her three-year-old grand nephew Roger. Together they would explore the woods and tide pools that surrounded her cottage, experiencing what only a Maine summer can offer. She also shares her belief that as we age our sense of wonder becomes muffled, an exiled prisoner with self-imposed blinders to a natural world that wants to have a conversation with us.

The child experiences wonder every day. Their open eyes, open ears, their words of joy, speak directly to time spent in the natural world. As Carson points out, to walk within nature and to do so with a child or one who still has that child-like exuberance of seeing something for the first time make that experience for all involved momentous — an experience that winds its way to the core of what makes us human. Carson’s prose speaks to what we experienced with Mary together as a family — making moments miraculous.

The child experiences wonder every day. Their open eyes, open ears, their words of joy, speak directly to time spent in the natural world. As Carson points out, to walk within nature and to do so with a child or one who still has that child-like exuberance of seeing something for the first time make that experience for all involved momentous — an experience that winds its way to the core of what makes us human. Carson’s prose speaks to what we experienced with Mary together as a family — making moments miraculous.

A few years later Mary succumbed to cancer. Her legacy remains in the memories carried on by her friends and family each in their own way. For me, whenever I experience something new while taking a walk along the shoreline, through woods and fields, on the ocean or high up on a granite bluff gazing out into nature, I think of Mary. I thank her for helping me know better this gift that is Maine. I can still hear her laughter to this day.

My Mom (left) and Mary

To spend time outside with a child is to experience wonder from long ago; the air is new and both flora and fauna light a path not to be missed. Young and old take each other’s hand, treading slowly, lightly, sharing and becoming that sense of wonder just like Carson was able to do with Roger. Her wish was that everyone could keep that child-like sense of wonder intact forever.

“If I had influence with the good fairy who is supposed to preside over the christening of children, I should ask that her gift to each child in the world be a sense of wonder so indestructible that it would last throughout life, as an unfailing antidote against boredom and disenchantment of later years, the sterile preoccupation with things that are artificial, the alienation from the sources of our strength.”

I believe that our sense of wonder is still within us and is always a part of who we are, no matter the circumstance. But we misplace it sometimes because of all the distractions, all of the “noise” that surrounds us.

This world is forever changing, and it is quite easy to get caught out in the storm. But so, too, like that carnival merry-go-round we all remember, it goes around so very fast, yet we can slow it down with our child-like eyes and imagination. We see it and we wonder at its immense beauty, stopping it in our thoughts for just a moment so we can reach out and grab that brass ring.

© 2022 RJ Heller

First Published: The Quoddy Tides, September 23, 2022: Machias Valley News Observer, October 5, 2022: Calais Advertiser, October 6, 2022: Bangor Daily News, November 1, 2022

The post That sense of wonder appeared first on RJ Heller.

January 13, 2023

A Valentine tribute to a couple’s devotion

A day is just not a day unless you see Lois and Vernon Sprague walking in Starboard. To see them walk the road together is like grabbing that first cup of coffee in the morning. The man is tall, broad-shouldered, always with his walking stick; the woman is petite, her arms in motion like a runner and always smiling.

Celebrating their 68th wedding anniversary and now living in Ellsworth to be closer to family, the two still make occasional visits back to the place they love. As time softens life’s edges, it’s nice to look upon a life of two who live life so well and so very full.

Celebrating their 68th wedding anniversary and now living in Ellsworth to be closer to family, the two still make occasional visits back to the place they love. As time softens life’s edges, it’s nice to look upon a life of two who live life so well and so very full.

The first time they meet they are teenagers in Starboard. Lois Ingalls is visiting her family on Ingalls Island when Vernon and a cousin arrive by rowboat. She quips, “What are you doing on my island?” He, ever-quick, responds, “Well, just show me where the two-fifths of the island my grandmother owns are and I’ll go stand over there.” This simple exchange reveals the essence of their relationship.

In high school he plays basketball for Machias, while she cheerleads for cross-town rival Washington Academy. A budding relationship begins, even though they are rivals and graduate two years apart. He drives truck delivering soda and ice cream, and she is a telephone operator in Machias. The two are now a couple, as a relationship blossoms and eventually blesses them both.

In 1952, the U.S. Air Force beckons, and he trains at bases in Texas and New Jersey working the flight lines, refueling fighter jets. A couple of years later, he deploys to Korea as a member of the 4th Fighter-Interceptor Wing. Upon receiving his orders he turns to her and says, “You are going to marry me, aren’t you?” They do marry and honeymoon at Bog Lake, where a covered chimney surprises them both with smoke, soon accompanied by a rescue party of friends.

Once he ships out he asks her to live with his family. Upon his return just a year later, they move to an apartment in Auburn N.Y. There he finishes his military service. Realizing the constraints of an apartment— evidently Lois likes to play music really loud— they purchase a trailer. Later, using his discharge pay they have it moved to his parents’ home in Machias where she can play “Side by Side” sung by Kay Starr as loud as she wants.

Vernon eventually takes a job with D.W. Small & Sons transporting heating oil and gasoline from Bangor to Machias. This is when a step in life becomes a great stride for a family of two. They purchase their first home close to work, and a daughter arrives in 1955, followed by three sons.

Vernon eventually takes a job with D.W. Small & Sons transporting heating oil and gasoline from Bangor to Machias. This is when a step in life becomes a great stride for a family of two. They purchase their first home close to work, and a daughter arrives in 1955, followed by three sons.

Teaching himself accounting he moves up in the company, and Lois is now an office assistant. On weekends they teach Sunday school classes, help in the nursery and operate a Christian bookstore out of their home. In 1986, Irving Oil purchases D.W. Small & Sons, and he finds himself working for a new company alongside his daughter.

In 1990, they return to Starboard, where they build a home on property once owned by his grandparents. It is here they make many friends and become active in a community club whose office is a one-room schoolhouse. It is here they begin their daily walks and contribute to the essence of this place affectionately called “The Cove.”

In these twilight years, he sits and reflects while working with puzzle pieces, harkening back to those long ago days of woodworking, buried treasure, fishing and accounting computations; she, engrossed in genealogical research, continues tracing their family lines back to the very beginning, while their ever-expanding family grows and moves forward with eight grandchildren and six great grandchildren.

Anyone meeting Lois and Vernon Sprague for the first time would have the same experience. You would knock on the door looking for someone to tell you about this place called Starboard. She would answer, smile and invite you in to talk. Later, you leave feeling like their neighbor and friend.

Anyone meeting Lois and Vernon Sprague for the first time would have the same experience. You would knock on the door looking for someone to tell you about this place called Starboard. She would answer, smile and invite you in to talk. Later, you leave feeling like their neighbor and friend.

And perhaps while there, he would say to you, “You know, I was the smartest boy in my 8th grade class.” He would then show you a large class photo and smile; he is the only boy in the picture. It is then, perhaps, you think Lois and Vernon Sprague are a testament to longevity and what love can be when given respect and devotion with healthy doses of friendly talk and humor sprinkled in daily, and, you would be right.

© 2020 RJ Heller

Originally published The Quoddy Tides: February 14, 2020

The post A Valentine tribute to a couple’s devotion appeared first on RJ Heller.

November 15, 2022

A paler shade of red?

A boat moored to holy ground waits, then waits some more. Traps on the hard remember old days and old ways. Fishing gear hangs in closets, basements and garages. The gulls are silent for they have no one to talk to. Painted buoys age dull in bright sunlight as a day begins silently on wharves Downeast.

*******

Since I was a young boy my favorite color has been blue. Today, red is the color that saturates my view and that of an entire Downeast community. In schools, restaurants and businesses everyone is donning red in support of the lobstermen and women who work these waters. It is yet another example of how this community comes together when one of their own needs help.

After a federal court loss, Sea Watch having red listed lobster and plans for additional federal regulations, Maine’s lobster industry is reeling. Add to that the exorbitant cost of fuel this past summer, bait shortages and low market prices for a catch worth $125 million just a year ago in Washington County alone, one would think this fishery is down for the count.

After a federal court loss, Sea Watch having red listed lobster and plans for additional federal regulations, Maine’s lobster industry is reeling. Add to that the exorbitant cost of fuel this past summer, bait shortages and low market prices for a catch worth $125 million just a year ago in Washington County alone, one would think this fishery is down for the count.

Yet the fishery continues to invest in its sustainability while continuing practices to curtail any chance of a life-threatening interaction with the North Atlantic right whale. And with its appeal in federal court being upheld, the Maine lobster fishery will continue to still be heard.

Confounding to me are the federal organizations trying to protect one life while not hearing the voice of another way of life. It is — if all are being honest — the premeditated demise of one life for another. And all of it based on circumspect data. The last documented entanglement of a right whale in Maine waters occurred in 2004.

Aggressive off shore fishing regulations — including seasonal closures, a significant decrease in the number of traps per fisherman, to ropeless traps — impact everyone who makes a living on the water. It truly is a domino effect. With these proposed regulations, smaller areas of water will become congested, causing working wharves to be inundated with fishermen needing to fish closer to shore, to make a living.

One would think before life-altering decisions are made that due diligence would include quality time spent in this Maine place — not from afar with charts and graphs. This should be the least owed to those who live and work these waters. Real decisions impact real lives.

Picture blue water in summer staying blue. No longer punctuated by a rainbow of bold colors, striped and tagged with a personal note attached — a love letter of tradition — from a fisherman to family, to a community. What are traditions if they are not met by a longing to preserve their intent, their purpose, to maintain a livelihood that sustains a family for generations?

We share this planet with many living creatures. No one wants to wipe out any species, let alone the whales that dot these waters They, too, bring revenue to the shore by way of tourism, bring smiles to faces drenched in sea spray as cameras point into the blue in hopes of catching a glimpse of fin, tail or a gentle roll by these gigantic gifts.

The Maine fishermen know how not to spite the very place they work. Efforts from all fishermen and women here in Maine have proven this place is indeed holy ground, like the home they leave every morning to the boat they step onto. The diesel smell pulsates through the air, through hardened veins and the deepest of hearts. They know they share the waters with other lives.

Miles of floating rope have been replaced by sinking rope; weak links were added to trap gear; more traps are fished per single buoy line and gear are marked for better traceability. All of these efforts illustrate the fact that the life of one species can improve while sustaining that of another.

I have a soft spot in my heart for those who ply the waters to put food on our table. They make a living doing what generations before them have done. Their boats that ply these waters are ornaments on a tapestry of hard work, perseverance and a deep respect to a sea that both gives and takes. And the sea does take.

Memorials to those lost doing what they love run up and down the coast. The gulls float above their memories on ribbons of air. Their legacy and the future for those who want to fish, all amidst a Downeast place that needs them to fish and harbors it all, must endure.

© RJ Heller 2022

The post A paler shade of red? appeared first on RJ Heller.

November 3, 2022

A Countryman’s Journal: Views of Life and Nature from a Maine Coastal Farm

“We didn’t come here to escape anything but to find something” – Roy Barrette

I am now better for having read Roy Barrette’s observations of life lived on his coastal farm in Maine. The 77 essays in Islandport Press’s reprint of Barrette’s 1981 book, A Countryman’s Journal, provide a full circumnavigation of a life first realized and then lived to its fullest on a piece of Maine land that was both accommodating and now humbled by his presence.

Leaving Philadelphia in 1958, Barrette and his wife Helen move to a rundown farm in Brooklin to make a life of quiet, simple pleasures. They succeeded in doing just that. Barrette’s attentive voice captures for us all his modest embrace of a place that continually gives back.

Leaving Philadelphia in 1958, Barrette and his wife Helen move to a rundown farm in Brooklin to make a life of quiet, simple pleasures. They succeeded in doing just that. Barrette’s attentive voice captures for us all his modest embrace of a place that continually gives back.

For 12 years Barrette shared that experience in his weekly award-winning column for The Ellsworth American and The Berkshire Eagle. These essays also made their way into DownEast and Yankee magazines. In addition to this book Barrette also wrote A Countryman’s Bed Book and A Countryman’s Farewell before his death in 1995 at the age of 98.

Like the writings of another famous Maine farmer, Barrette’s prose rings loud. In meetings over martinis to discuss current events, the finicky ways of farm animals or the seasonal machinations that are farm life, his neighbor E.B. White provided not only friendly advice but, also, another writer’s view of the world. What I would have given to be present with those two while they talked away the hours about the whims and ways of a world that stops for no one.

These essays are not a memoir of a person but that of a person’s relationship with a place — a coastal farm tucked between folds of wooded fields and the sea. The words take you there, sit you down on a rock or a stump amidst shadows of sunlight and fog trails and reveal the unfolding life of a farm, the farm Barrette named “Amen Farm.”

Covering topics of everyday joys, angst and uncertainties, his writings do not disappoint. Barrette is quick to the point, as is the case with most columnists knowing there is an editor out there somewhere, red pen in hand, counting words. For the reader, these essays flow without effort, telling not only a story but serving up a slice of Maine life as only a seasoned writer can do.

In the opening essay, “Life in the Country,” Barrette admits the life of a rural columnist is somewhat easy, in that the readers he hears from more or less want to thank him for his observations. Some do so by visiting the farm. They also will leave a bit of themselves in the process, which he knows will fuel the fire for more columns and in many ways reaffirms what country life is all about.

“People here are always giving each other something, without any particular end in view, because that is the way we live. We had a party not long ago at which we served mussels marinières. I was trying to figure out the tide so I could get some at low water, when a young friend showed up with a peck of them as a gift. I don’t know yet what I am going to do for him, but sooner or later some opportunity will develop.”

In “Property Lines” the land and where it begins and ends allow a philosophical outlook to rise for those who feel they must own all of the outdoors in order to keep others from owning land next to theirs. “Well, that’s one way of owning all outdoors, but I have a better way and it doesn’t cost anything. I just walk, and listen. What I take off the land is invisible. You can’t prove damages when all that has been stolen is the fragrance of the balsams, the autumn fire of the maples, the scream of the blue jay, and the whisper of the wind in the pines.”

And in “Pardon the Past — Give Grace for the Future,” Barrette speaks to our penchant to close out the old year by feeling we must make resolutions towards a new year. He even disagrees with Thoreau on this matter. “I am afraid I cannot agree. I have lived to be older than Henry was when he died and believe that had he lived longer he, too, might have thought differently. We countrymen, even when we grow old, still spring with the spring, and if we no longer make New Year’s resolutions it is not because we are unmindful of our shortcomings, but rather because time has taught us that it takes more than resolutions to gather figs from thistles.”

Having thoroughly enjoyed this book, I can now say that the shelf in my study devoted to books of and about Maine is complete. Barrette’s book is one of two bookends holding the stack up straight, like that of a rock wall that meanders unhurriedly through a Maine field. The other book is One Man’s Meat by E.B. White — two forever storytellers who both imbue a certain essence when it comes to a life lived in Maine.

Islandport Press, 2022, softcover $18.95

© 2022 RJ Heller

First Published: The Quoddy Tides, September 23, 2022 : Machias Valley News Observer, October 19, 2022: Calais Advertiser, October 20, 2022: Bangor Daily News, November 14, 2022

The post A Countryman’s Journal: Views of Life and Nature from a Maine Coastal Farm appeared first on RJ Heller.

August 1, 2022

Finding the most unusual things every day

“I am wanting to go and find Frog Rock,” my friend said with a sly smile. I waited to see if he was serious. He was.

Now having spent seven years living here, there are few things that surprise me. But going to see a rock shaped over time and eventually named “frog” seemed intriguing, to say the least.

Our journey began one sunny afternoon in September before the pandemic changed life for good. My friend has wanted to do this trip for years, but, like much in life, this one morsel of time just seemed to be skipped over in pursuit of other, more important, items on the list. He and his wife would spend a couple of weeks every summer at their cottage in Starboard. During their visits my friend always shared a couple of “did you know” type stories. By the end of their summer stay I would know a little bit more about the Down East area where we live. Their subsequent visits and our conversations would always be an education for me. Frog Rock was one of those stories.

He and his wife arrived to pick me up. We sat in the car at the bottom of the driveway. My friend could hardly contain his excitement. He began showing me a file – yes, a file – he compiled with various articles, notes and maps all about this geological stone oddity. We sat there as I perused his notes which oozed intent to find this large, frog- shaped rock, now in Technicolor, having been painted some time ago and located somewhere in Washington County.

This stone anomaly sits in an area within the fabled blueberry barrens running for miles through and around Cherryfield, Columbia and Deblois. Dissecting the barrens is the baseline road, which is a story unto itself. In short, the 5.4 mile-long Epping Baseline Road was the last of seven “baselines”— a perfectly straight surveyed line used by the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey for triangulation to establish positions for mapping the North Atlantic and East Coast in the 19th century.

Traveling into the barrens is like stepping onto another planet. There are moments when you can easily end up going in circles. During our journey, at times, it did seem as though we were lost and would never find what we were looking for, or, for that matter, our way out once we finished. But once finding it, walking right up, placing a hand on the colored stone and seeing the size and girth of the rock cause one to pause. The rock resembled that of a frog relaxing in a field of green, with bits of blue glistening in the light amidst hints of deep scarlet as the barrens begin to sleep with autumn’s arrival. The quiet invades, and life at that moment comes to a screeching halt. It’s a weird yet joyous feeling, to be with friends seeing something for the very first time and sharing that moment.

I look out and see more than what I came to see. While taking in the vast expanse occupied by the barrens, I cannot help but wonder how on earth did this rock come to rest right here on this very spot? With an imaginative mind, the creation of the world can be gleaned from a casual stroll through the barrens. Traces of glacial nudges, lost lakes and primordial dew abound.

Living life Down East is one long journey, if you think about it. The path can lead you most anywhere, physically and spiritually. There is boundless beauty everywhere. All you have to do is take the time to see it and realize what seems special and unusual to the visitor is home for us. We are given the opportunity every day to see and experience some very special things, such as: vibrant colors from trees and ground, beaches of multi-colored stones and granite; blooming fog, crazy tides, one-of-a-kind sunrises— the very first to be seen in the U.S.; fishing boats leave and return every day like clockwork; haunting sea smoke, lighthouses flashing smiles; and on this particular day, a rock, shaped like a frog, dressed in colors that complement, with a slight smirk running from cheek to cheek. Do frogs even have cheeks?

After we packed everything up and took one last glimpse of the barrens in all their glory and said our own personal goodbye to “the rock,” there was a silence shared between the three of us — each of us taking in the moment, processing it in our own unique way before turning away to head back to our own lives, having now crossed off another “to-do.” My friend settled in behind the steering wheel and with a click of his seatbelt turned to me and said, “Next year, let’s find Snake Rock.”

The post Finding the most unusual things every day appeared first on RJ Heller.

June 29, 2022

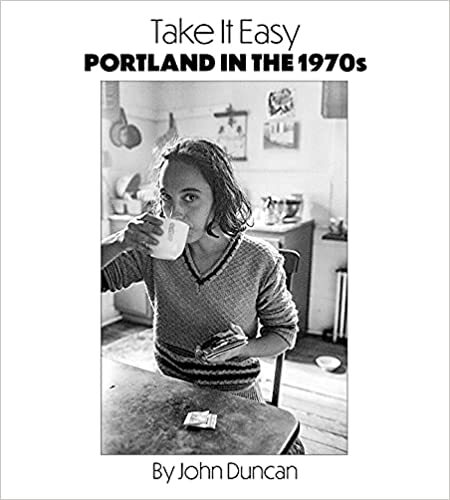

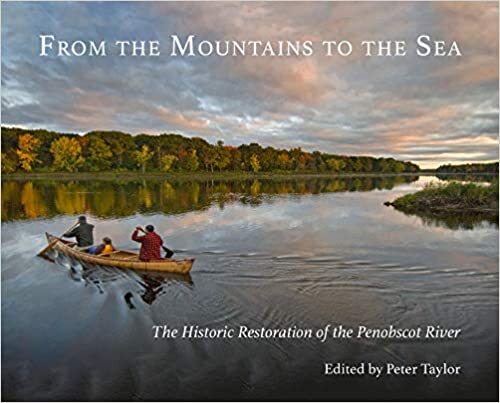

Take It Easy – Portland in the 70s & From the Mountains to the Sea

Two books found me. One took me back in time with black-and-white images of a city during a decade I often think about. The other informed me of “what might have been” by showing me in text and color images of what eventually became reality for a river. Both books, separately and together, are about Maine.

A photograph can be powerful. Without words, a visual image snapped at a specific moment in time captures that time. It also captures both the subject and the photographer taking the image or, better yet, “making” the photograph. In the wonderful book, Take It Easy – Portland in the 1970s, photographer John Duncan’s work reveals an artful focus on both place and person during a decade of pure change, not only of Portland but the entire country.

A photograph can be powerful. Without words, a visual image snapped at a specific moment in time captures that time. It also captures both the subject and the photographer taking the image or, better yet, “making” the photograph. In the wonderful book, Take It Easy – Portland in the 1970s, photographer John Duncan’s work reveals an artful focus on both place and person during a decade of pure change, not only of Portland but the entire country.

Duncan’s collection of back-and-white negatives captures Portland — specifically Congress Street — during a decade that saw change as a constant. The book of photographs is arranged in four sections: family, places, memories and work. The 130 images showcase a talent Duncan was perhaps unaware of, because the photos feel as though a simple, human interaction of sorts has taken place. The camera, the photographer and the subject are communicating to one another, as if a casual conversation is happening on a street corner. Then, with the click of a shutter the story is revealed.

Duncan, now retired, is surprised at the notoriety this collection has brought him yet remains humble in retrospect. Never professionally trained, Duncan was a cab driver simply snapping photos of what he saw. The photos accumulated, and then a conversation turned into a professional collaboration with Islandport Press.

These are powerful photos of common moments in time that captured the essence of a place, a city’s cultural presence in time. And as we know all things move forward; the future interceded; change continues for the city, while Duncan’s snapped frames of time will linger in the ethos of its past.

*******

Rivers abound in Maine. One of those rivers is the mighty Penobscot River. Its history is as varied as that of Maine itself and beyond. In Peter Taylor’s book, From the Mountains to the Sea, a journey of restoration is explored in words and photos, culminating in an unlikely collaboration between people and organizations.

One June day in 2016, an Atlantic salmon made its way upriver through the town of Howland, bound for spawning grounds that had been blocked for 200 years. This single historic event came on the heels of a lot of work involving the innovative removal of dams with no net loss of hydropower. It also involved many people and organizations from diverse backgrounds coming together to make a dream into a reality.

One June day in 2016, an Atlantic salmon made its way upriver through the town of Howland, bound for spawning grounds that had been blocked for 200 years. This single historic event came on the heels of a lot of work involving the innovative removal of dams with no net loss of hydropower. It also involved many people and organizations from diverse backgrounds coming together to make a dream into a reality.

Taylor is president of Waterview Consulting, an organization that helps clients advance environmental initiatives. Before that he worked as a travel magazine editor, university science writer, freelance writer and photographer. He has degrees in biology and ecology, and for more than 20 years he has specialized in telling stories of ecology and conservation.

The Penobscot River is a legendary river. Logging camps once lined its banks; Indigenous people then and now hold the river in reverence. It not only is a place for them to fish, but it is a spiritual place that holds their 10,000 year-old story as a people together. Thoreau paddled its west branch, and in doing so, learned as much about the river as he did about the Native Americans who lived along it.

“A long time ago, The People lived along this river, as we still do now. We take our name ‘Burnurwurbskek’ from a place on the river, and later the entire river took its name from us.” — Butch Phillips, Penobscot Tribal Elder

Over decades of development, the river declined. Fishing grounds went silent as hydroelectric dams were built. And then in 2001 an unlikely alliance of organizations and people came together. The Penobscot Nation working with the Atlantic Salmon Federation, Natural Resources Council of Maine and The Nature Conservancy acquired and removed human-made dams allowing the waters to run free. This is their story of how they did it.

Reading this book was as if I was in a birchbark canoe seeing the yesterday of a river from a new perspective all because of like-minded people devoted to a single purpose — rescuing a river. I float within its current, and as I move with it, I can see the river move backwards in time as fish and other wildlife return, as life returns. Restoring something back to its original essence is a beautiful thing, and this book captures the spirit of it all.

So whether you are looking to step back in time with images that showcase the essence of life in Portland during the ’70s or to experience a historic project that will have lasting impact on the future of flora, fauna and the people living along the Penobscot River, both of these books should be your constant companions on that journey.

Take It Easy – Portland in the 1970s By John Duncan. Islandport Press, 2021, softcover, $19.95

From the Mountains to the Sea – The Historic Restoration of the Penobscot River By Peter Taylor. Islandport Press, 2020, softcover, $24.95

© RJ Heller 2022

First published, The Quoddy Tides, Eastport: May 27, 2022 / Published Machias Valley News Observer: June 15, 2022 / Published The Calais Advertiser: June 23, 2022 / Published Bangor Daily News: June 27, 2022

The post Take It Easy – Portland in the 70s & From the Mountains to the Sea appeared first on RJ Heller.

Life Downeast

- R.J. Heller's profile

- 7 followers