Jose Vilson's Blog, page 41

August 13, 2014

When Can We Talk About Race? (Michael + Trayvon + Renisha + …)

This is often the way education conversations go:

Higher-Up: Hey, so what do people want to talk about?

Teacher 1: Can we talk about teacher evaluation?

Higher-Up: Sure, what’s on your mind?

Teacher 1: Well, here it goes. [long diatribe about how great / terrible Danielson is]

Higher-Up: Well, OK. Anyone else?

Teacher 2 (of color): Can we talk about race now?

Higher-Up: Sounds complicated. We need a more appropriate forum for th …

Teacher 2: But this is urgent. We’re having serious issues going on and so many of our kids are of …

Higher-Up: OK, OK, OK. We’ll get to it in a more appropriate forum. Anyone else?

Teacher 3: Let’s talk about Common Core.

Higher-Up: What about it?

Teacher 3: My thinking is [even longer diatribe about Gates' involvement and how great / terrible standards are for kids]

Higher-Up: I hear you. That’s relevant. Anyone else?

Teacher 2: Can we talk about race now? (with a little more emphasis)

Higher-Up: I still don’t think we’re ready. We’re really dealing with this issue and I’d rather we be better informed and nuanced about race before dealing with it.

Teacher 2: But half the people here don’t actually know what the CCSS is, the layers, and why they’re either for or against any of it and …

Higher-Up: SO everyone should have an opinion on the CCSS, so I allowed it.

Teacher 2: UGH!

(skip to the last teacher on the list …)

Higher-Up: Anyone else?

Teacher 100: I want to talk about the deleterious effects of poverty …

Teacher 2: OK, so are we going to talk about race here?

Higher-Up: Now, I said we needed the right forum …

Teacher 2, agitated: NOOOO! YOU WAIT FOR THE RIGHT FORUM! ALL Y’ALL HERE TALKIN’ BOUT ALL YOUR SINGLE LITTLE ISSUE BUT DON’T WANT TO FACE UP TO THE REALITY THAT OUR KIDS LOOK A LOT DIFFERENT THAN OUR STAFF, THEY DON’T WANT YOUR STINKING MIDDLE CLASS / UPPER CLASS VALUES, AND WANT TO KNOW WHY PEOPLE OF COLOR JUST LIKE THE ONES THEY SEE IN THE MIRROR ARE GETTING SHOT WITH NO CAUSE BY THE PEOPLE WHO ARE SUPPOSED TO PROTECT THEM!

Higher-Up: Now, now, let’s stay professi …

Teacher 2: YOU CAN STICK YOUR PROFESSIONALISM UP YOUR …

And scene …

So, not that this has happened before, but I wonder, too frequently, why people always want to wait, wait, wait on discussing issues of race, even ones as point-blank (pardon the pun) as this Michael Brown tragedy. Whether on or offline, people always want to find the “right forum” for this conversation. I get that, with some discussions, we need to have certain protocol so people feel comfortable opening up about their experiences and, in many cases, unpacking their privilege. But then it always feels like people put off certain conversations until people forget them.

All the while, I must openly question how folks can go so hard when it comes to Common Core State Standards and all the reforms that come with it, and not dedicate a few minutes of their time to learn about, if not ask those who know something about, some of the tragedies affecting our kids, both locally and nationally. I refuse to stand in solidarity with those who won’t do so with me.

Because the death of children of color at the hands of our executive branch takes more precedence than any set of standards.

I won’t wait.

Jose

The post When Can We Talk About Race? (Michael + Trayvon + Renisha + …) appeared first on The Jose Vilson.

August 7, 2014

Eduflack’s Review of This Is Not A Test, For Argument’s Sake

Today, Patrick Riccards of EduFlack wrote a review of my book This Is Not A Test, and it moved me in a major way. Read this excerpt:

But most importantly, I walked away thinking I want someone like Vilson to be teaching my kiddos. This is a teacher who cares and a teacher who is making a difference each and every day he steps into his classroom. We may disagree on the finer points of testing, with me hoping he would give more credit to the value of interim assessments in improving both teaching and learning. But there is no disagreeing that Vilson gets it. He knows what we are doing right and what we are doing wrong in the American classroom. He cuts through all of the flowery language and platitudes and excuses we hear far too often, and speaks truth on issues where honest truth is often absent. And he lays out issue after issue that I want to further engage him on, have a deeper discussion of, and, yes, try to change his mind about.

This.

I have a plethora of great reviews from friends, colleagues, and folks who agree with my edu-politic. But this one was special because, even though we’ve had good conversations on Twitter, I didn’t think we had much in common. When it comes to assessment, we’re as “opposite” as can be. I’m up for debate on most days when we . I don’t play the edu-jargon games, so that makes it harder to paint me in a corner. Also, I understand, though not always agree, other viewpoints other than my own, which is important as a classroom teacher and an education writer.

I’m a firm believer that listening to other arguments can, at times, makes one’s own argument stronger.

Yet, I’m glad it got through to Patrick because it lets me know that this idea of two sides of ed-deform is nonsense and that we can develop different approaches depending on the conversation. He also took it back to his own experiences as a father. That matters for me. He thinks he’s going to sway me on some things. He won’t, but it’s good to know that I served him food for thought. Please read what he said because it really was heartfelt and tell him what you think.

We’ll call it peace meal.

Jose

The post Eduflack’s Review of This Is Not A Test, For Argument’s Sake appeared first on The Jose Vilson.

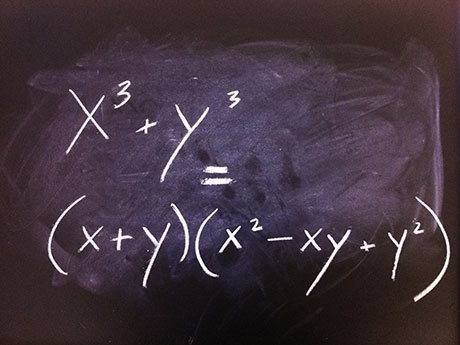

Another Reason I Don’t Like FOIL In Math

I recently wrote an article for Edutopia about factoring polynomials using areas and why FOIL is absolute crap:

For one, I’m not a fan of FOIL (first-outside-inside-last) for a plethora of reasons. While I think it’s handy to have an acronym that reminds students of a procedure, it only works in a very special case. In this case, FOIL works only for multiplying a binomial by another binomial. Does FOIL lead students toward understanding multiplication of all types of polynomials, or understanding why the distributive property works even with variables? I’m not so sure.

Please do let me know what you think about it! And please do encourage me to write more about math. I could use it in the coming school year!

The post Another Reason I Don’t Like FOIL In Math appeared first on The Jose Vilson.

August 5, 2014

Personalization Depends On The Person

Any so-called innovation deserves a second and third look when it’s brought to kids, even if it’s from Sir Ken Robinson. I saw this in my timeline, which says the following:

“Education doesn’t need to be reformed – it needs to be transformed. The key is not to standardize education, but to personalize it, to build achievement on discovering the individual talents of each child, to put students in an environment where they want to learn and where they can naturally discover their true passions.” – Sir Ken Robinson

Whenever anyone mentions personalization, it usually involves some sort of tech, akin to extreme differentiation. Some folk have bastardized the word to include folks like Khan Academy or Rocketship, where the tech is more important than the pedagogy. Children get a responsive program in front of them that moves along depending on correct answers, but that’s responsive, not personalized. Slight difference.

Let me preface my forthcoming critique by saying that I do believe in personalization generally. I think we need to better direct our school system so that students can discover their own paths without feeling like they’ve failed some ominous adult’s expectations. I generally think students have to go a certain route because that’s what society says, within reason. We don’t have enough student voice in education, and fostering students voices matters in any democracy.

Having said that, personalization also depends a lot on the person doing the personalizing. Some of my favorite youth activists (thinking Stephanie Rivera and Hannah Nguyen here) always remind me how adults love to impose their adult issues onto kids. “Personalization” means different things. Some kids really don’t know the things they’re capable of. Some adults, neither.

Personalization looks different across race, class, and gender lines. For example, when I tell you how many teachers just want to dump kids in vocational schools or alternative schools when it’s not necessary without asking them, that’s a problem. Some adults are still so caught up with which jobs some kids deserve and who looks good for which jobs that, if we take personalization the wrong way, we’re going back to making choices for kids at times when we can make choices with them.

We need appropriate baselines, too, and a timeline for when adults should make suggestions for their education. It’s a touchy thing, and we need our system to be much more responsive than it currently is. Personalization is more powerful when, as educators, we show students other doors and let them decide. We’re just giving them tools. However those tools look like, at least we’ve given them more pathways than were originally available to them without us.

But that’s none of my business. Ain’t nothin’ personal.

Jose

The post Personalization Depends On The Person appeared first on The Jose Vilson.

July 31, 2014

Here It Is, A Profession Transformed

I just got back from three packed-house events in Chicago, Chapel Hill, and Philadelphia in July. In each space, the energy in the room took me aback because I’m still not used to the idea that a bunch of folks with busy lives want to hear my mouth run for two hours. Yet, by thinking that I don’t belong on that stage or on that mic, I perpetuate the power structure which often leaves teachers like me from believing we can set the table in education.

For instance, the Woodrow Wilson Foundation invited me to speak to 500 new teachers from all across the states about teacher leadership. This decision came shortly after they projected that only 5% of the teaching workforce would be of color, woman or man (it’s at 18% now). For a moment, instead of saying, “Yes, of course I’m a natural choice!” I thought, “Wow, why me?”

I thought long and hard about what I might say to a group of burgeoning teachers and the sort of energy they needed to bring back to their schools. All of a sudden, something pulled me back to those first years, and the reason why I saw myself breaking away from the traditional routes of teaching. Our current school systems (and the people who inhabit them) force their visions upon us. They implore us to go into administration if we’re motivated individuals. They almost force us into dean roles or central roles if we have other talents outside of teaching (and even excellent teaching isn’t part of the equation for many leaders). Seeing these folk, quietly listening to them, and hearing that sense of optimism and disappointment in their districts took me to a place where I offered myself as the change I wanted to see.

I didn’t want to, nor still want to, be famous.

The issue with so many of us is that we’re so quick to douse the flames of our brightest without even knowing the source of their flames. Anyone in my intimate circle will attest to how grateful I am for these opportunities, but I also see how any sense of fame in education, especially for a teacher, can become notoriety, infamy, and unwarranted antagonism. Unlike other professions, like writers, doctors, and college professors, teachers are too often asked to put their head down in the service of others.

To some extent, this argument has validity. We do have a set of folks who only teach as a stepping stone and don’t actually get better at their teaching. Also, collaboration and team building are critical to any school environment whereas competition amongst staff members doesn’t improve collegiality. On the other hand, it suggests that we can’t simultaneously shine bright individually and collectively and still get better at our craft by sharing their passions. When I first mentioned the idea of celebrity teachers, I mentioned this as a tongue-in-cheek comment about society’s views of teachers. Now, I’m far more convinced of how even our most progressive institutions rarely handpick teachers to speak unless a) that teacher follows the “message” or b) that teacher rumbles.

I generally fall into b. Because of this, I use my platform to elevate as many folks as possible, and hoping to multiply that energy so others can pass it on. In places where teachers are given scripted lesson plans from publishing companies, where governors argue whether teachers should get paid a little less or a little more than minimum wage, where the ostensible representatives quip that they will shut down an entire school system because they feel like it, it’s critical to have folks who want to take that extra step and say “Something’s not right here.” Teachers rely too often on someone outside of K-12 education to empower them when we could easily do it ourselves.

Before her passing, Maya Angelou left us a jewel about the difference between humility and modesty.

“‘I don’t know what arrogance means,’ she said. ‘You see, I have no patience with modesty. Modesty is a learned adaptation. It’s stuck on like decals. As soon as life slams a modest person against the wall, that modesty will fall off faster than a G-string will fall off a stripper.’

[...]

“Whenever I’m around some who is modest, I think, ‘run like hell and all of fire,’’ she said. ‘You don’t want modesty, you want humility. Humility comes from inside out. It says someone was here before me and I’m here because I’ve been paid for. I have something to do and I will do that because I’m paying for someone else who has yet to come.’”

And so it goes, and I implore everyone who’s gotten these opportunities to see them as gifts, and the way we honor them is to push them to your limits. Lead from the front, back, or the side. Set an agenda separate from whatever the current education debate is or with the current agenda in mind. Be proud of your gifts and use them wisely.

Whether it’s 30 folk, 100 folk, or 500 folk, we are the teachers who will slightly transform this, make it a bit of a break from the norm …

Jose

The post Here It Is, A Profession Transformed appeared first on The Jose Vilson.

July 27, 2014

Reframing Expertise in Education (The Habitual Line-Stepper)

In my travels this summer, I’m often asked to ponder this idea of expertise, and specifically, how education researchers and those in higher education can help K-12 teachers.

Since I entered the teaching profession almost a decade ago, I’ve had this struggle with this idea. From articles where a writer with a PhD in education lays out a plan for how school systems should be run to speeches where a professor from a prestigious college tells us why the Common Core will and must work, I’ve grown weary of the disconnected dialogue between well-meaning K-12 teachers and the plethora of college professors who’ve come to rescue American education from the vice grip of mediocrity.

Instead, I proffer the following: who is the real expert?

For instance, there’s a study out there (that I won’t point to for a multitude of reasons) that shows the difference between what K-12 teachers are currently doing with Common Core State Standards and what the writers of the CCSS think teachers should do with the CCSS. First, the writer of the study assumes that the expertise of educators comes second to those studying education from the outside. Second, it presumes that students aren’t variables all their own. Third, and consequently, it assumes that the teaching conditions set forth in places like Japan, Singapore, and Finland are equivalent, or at least negligible, to those in the US, and currently they aren’t.

Then again, who are teachers but the practitioners of the CCSS the experts have proffers to our local and federal governments?

Despite some districts’ best efforts to counter this, teacher expertise is necessary if any progressive change moves. Whether a teacher agrees or disagrees with the CCSS as a best practice may be second to whether a teacher can actually teach. Teachers can’t grow as educators if the only way they’ve seen teaching is through the lens of their own teachers. Our country readily discounts pedagogy because standards and their assessments are a much more accessible, short-term way to move education than revamping the idea of school for everyone involved.

More importantly, we discredit the knowledge students, parents, and others bring in a way that doesn’t get buy-in from all involved. The idea of accountability sits too often on the laps of teachers, and not the plethora of experts brought in to supposedly train them.

It’s dangerous for us to suggest that we reframe this idea of expertise. It’s dangerous for us to ask that we create a new table rather than having a seat at it. It’s dangerous for us to push back when TV shows, magazines, and even our teacher-friendly institutions highlight a certain type of expert over another. It’s dangerous for us to even ask who created these lines and divides over expert and teacher.

This is why we must step on the line, and, for many of us, jump over it and walk on.

The post Reframing Expertise in Education (The Habitual Line-Stepper) appeared first on The Jose Vilson.

July 15, 2014

Teachers of Color Caught In The Windmill (On Real Equity)

Last week, I delved a little deeper into this issue of teachers of color, hoping to sow some of the prevailing narratives up and construct something more cogent.

Yet, when it comes down to it, the lack of teachers of color is a symptom and not a cause of the education gaps we currently see.

Time and again, we get reports from former teachers of color about why they leave, and often, it’s the same symptoms for why teachers in general leave: lack of empowerment and autonomy, working conditions, and low pay. With teacher of color, education systems only exacerbate this problem because many teachers of color come back so they could give back to similar communities that they grew up in. Yet, they see some of the same deficiencies from their childhoods manifest in teachers’ lounges and observations about their colleagues. Because many teachers of color who come from similar neighborhoods they’re serving don’t have a family-established wealth to fall back on, they tend to leave at faster rates than the average teacher, too.

But there’s more. This research by Ivory Toldson done on this topic suggests that lack of teachers of color isn’t for lack of want, and that systemic elements of our education system will continue to put people of color at odds with their education system, regardless of whether it’s public, private, or hybrid (charter).

I’d take it one step further and say, why bring in more teachers of color into a system that continually ostracized the already disenfranchised? If teachers of color want to “give back” to the places they grow up in, then we have to consider why the neediest schools consistently get shut down, “turned around,” or transformed into a charter school, replete with uncertified teachers. If teachers of color want to go to schools where the children have similar experiences to them, then we have to wonder why we don’t make all teachers, regardless of race, culture, or gender, take cultural competency classes so teachers of color don’t have to teach both their students and their peers.

Because even the prospect of having more teachers of color threatens the status quo in a way that those who currently staff our schools aren’t prepared for. Too many folks think TOCs might take “seats” (see this comment by Renee Moore here). We aren’t. We can create more seats.

Because “education progressives” are perfectly OK with diversity as long as it doesn’t affect their specific school. Then, it’s a question about “dynamics.” Uh yeah. You should hope so.

Because some folks get mad at the new-found attention teachers of color have garnered, so someone quips, “Teachers of color are equally capable of being assholes.” If so, then why bring it up unless you’re nervous someone will take your seat?

Because we can’t address any of the shortcuts to equity without actually addressing the pillars of race, gender, and class across our education system. Without those honest conversations, I don’t see policies as anything more than a “We’re doing something for the sake of doing something” scheme.Because the symptomatic failures of our education system often doubly affect teachers of color: as the students they once were and the teacher they wish they could become. We can do better. Jose

The post Teachers of Color Caught In The Windmill (On Real Equity) appeared first on The Jose Vilson.

July 9, 2014

Teacher Quality And The Decline In Teachers of Color

This morning, I came across this article on Huffington Post (I know, I know, hear me out, though) and thought I should ask questions about President Obama’s initiative to enforce former President George W. Bush’s mandates for “excellent teachers” to stay in the highest-need communities. Read this:

President Barack Obama’s new initiative, titled “Excellent Educators For All,” seeks to ensure that states comply with the George W. Bush-era No Child Left Behind mandate by asking state officials to submit “comprehensive educator equity plans” that detail how states plan to put quality educators in classrooms with disadvantaged students. The Department of Education also plans to pour millions of dollars into a “Education Equity Support Network” and publish profiles of states and districts that have succeeded in promoting teacher equity.

For one, I’m usually skeptical about any initiative that attempts excellence when we haven’t defined (or even characterized) what actual excellence is. For instance, people often describe an excellent teacher as “caring,” but isolating “caring” as a characteristic would be short-sighted in terms of identifying the best teachers. Even something like the Danielson Framework can’t quite pinpoint because numbers aren’t always facts.

Secondly, I often see people who talk up teacher quality not address the issue of working conditions. People too often make working conditions and teacher quality a chicken and an egg argument. There were presumably eggs before chickens, and so it goes that working conditions of a school generally support good teachers and keep them. Of course, there will be special cases that don’t fit the mold, but that tends to be the way it goes.

Here’s the thing: in my observations, teachers of color will stay in underserved communities where others won’t.

If you look at the graphs for the full picture, you’re basically seeing that richer, whiter schools get more experienced, more educated (at least in number of degrees) and more certified teachers, which seems to contradict a few narratives, mainly that the number of years and degrees don’t matter in terms of student performance. While this might have some external validity, I don’t see how anyone would choose a school that doesn’t have at least some experienced, educated, and certified staff. Unless they’re in a private or charter school, where restrictions on degrees or certifications are more lenient, at least in most urban areas.

Unless they’re in the high-need neighborhoods, which is code for schools with poor students of color.

Teachers of color aren’t only needed in these high-need neighborhoods, they are predominantly in these high-need schools. This, among other reasons I’m sure, is why, when schools get shut down in droves as they have in the last decade, teachers of color lose their jobs with those schools. From the plethora of educators of color I’ve spoken to, with various degrees, experiences, and backgrounds, they stay in certain schools because they came into teaching to serve children of color, and aren’t necessarily looking for career advancement.

Yet, because the working conditions didn’t work and the systems in place were neither conducive nor supportive of children of color and their teachers, they either stay and hope to wither the storm or, increasingly with much younger teachers of color, leave altogether to pursue other education-related professions where they can work on behalf of students without being tied to the classroom.

That’s why, by 2020, we may see a drop from 18% teachers of color to 5% teachers of color, and with male teachers of color already at 3%, this may certainly perpetuate the inequity we’re seeing in student achievement. More importantly, this threatens to make schools feel less inequitable.

But our country stays taking shortcuts to equity instead of making a real investment. More on this soon.

Jose

The post Teacher Quality And The Decline In Teachers of Color appeared first on The Jose Vilson.

July 4, 2014

Digital Tools As The Gateway Drug To Real Pedagogy?

On Sunday, I spent some time with the good folks at SMART Technologies (yeah, I can’t believe I’m saying that either, but more on that later) for the annual ISTE conference, a mega-large education conference hosted this year in Atlanta, GA. SMART Technologies asked me to give some words of wisdom to their partners around student collaboration, one of my personal passions. They neither asked me to restructure my remarks nor ignore social justice issues, which if folks invite me somewhere, they should know that’s also where my heart is.

At some point, I got the chance to go to exhibit hall, and I should have taken a motion sickness pill. The dizzying array of tech tools and labels made my eyes cross. As I walked quickly through the halls, dodging salespeople left and right, I stopped every so often when I heard a company give a presentation about their particular product.

It got me thinking, as I always do, whether educators have made any real progress when it comes to thinking about pedagogy in the 21st century. Is it really the tool that’s the driver or the teacher? If, for a second, districts think that a product ought to be the focus of the pedagogy, then we again concede that a teacher’s expertise is only second to the dazzle and pizzazz of an attractive thing when it comes to student learning.

If, on the other hand, we put these tools in the hands of expert educators with supportive school systems, then that might make the shift more real. Any tool that we put in a classroom ought to center around actual student learning, and not the tool. I often find that many so-called 21st century schools spend far more time on training students and teachers on how to use the technology than trying to integrate the tool into a well-planned school system.

Central to that system is whether the teacher can teach, and if the tool can fit with the ebb and flow of a teacher’s day. Are teachers willing to learn something if it engages more students? I’m sure. But if, after trying the tool, neither the students nor the teachers adapt well to the tech, then that’s something to consider too.

Yet, if the pedagogy is there, then teachers can keep making mistakes without … a glitch. Err, a hitch.

The post Digital Tools As The Gateway Drug To Real Pedagogy? appeared first on The Jose Vilson.

June 26, 2014

You Can’t Educate With Us (On Tone-Policing When Silent)

I called someone a racist this past weekend. And a sexist for good measure.

I don’t have much authoritative experience with the latter as I do the former, and I don’t go throwing around such a title lightly.

I won’t go into the incident, but it was a long string of events that triggered me using the word, and, soon thereafter, people started opening up about some of the latent racist comments said person made. It was revelatory in that I had this hunch for a long time, but, because he’s respected in some of our common circles, I decided to let everything play out, letting karma mete out justice accordingly.

That moment never came, so I handled it myself.

Time and again, I’m faced with having to bring up conversations that made people’s collars tight around their necks. It’s not the happy-go-ISTE convo, the hipster affectations, the “standardized testing” is the devil conversation, or the “new progressives don’t believe in unions” nonsense. It’s the conversation around why we we’re still in the mentality of “saving the children.”

Every time we simultaneously say that we “speak for our children of color” but neither give voice to those children or don’t respect the very adults of color who were in the same seats, we set the foundation for angst, anger, and rage. The thing about discussions about race, sex, and class is that, if you’re the only person of the group most marginalized by the -ism, you almost feel like it’s your job to speak up UNTIL someone else gets the gumption to do so.

Especially in a field like education, where people want to believe everything is either hunky dory or everyone is working against them, people rarely speak up in a way that matters. When someone says something racist, they wait for me or one of my friends to handle it. When someone sexist comes up, they always wait for an out-and-out feminist to address it (and then the rest of us loud ones).

With the plethora of resources available to us (see here and here for some of mine), it’s wild that many folks still rather sit on the sidelines while the same folks have to bring up these harsh topics. Some will be brave, and, even just a nod or a “thank you” goes a long way in making the marginalized supported.

Sitting there, hoping for the vocal person of color to handle it just won’t do any more. Don’t wait to speak up with the marginalized, the ism’ed. Because, if you do, then you can’t complain how, after tireless battles and wearisome incidents, the tone isn’t to your liking.

Our voices got raspy, our souls depleted from the beating back of zombie stereotypes and slurs. If your voice has no intention of alleviating the voice, tone isn’t your angle for entry. You never spoke. Please. Have this whole row of seats.

Jose

The post You Can’t Educate With Us (On Tone-Policing When Silent) appeared first on The Jose Vilson.