Susan B. Weiner's Blog, page 57

December 1, 2015

“High net worth” in your financial marketing

A copyediting project spurred me to think about how to use “high net worth” to describe investors. First, should you hyphenate “high net worth” when using it as an adjective? Second, is “high net worth” a useful term for communications with prospective clients?

“High net worth” and hyphens

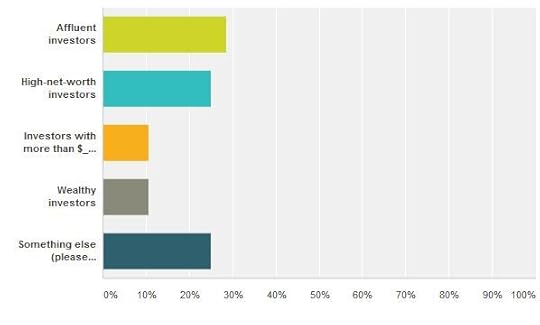

My gut told me to use hyphens in “high-net-worth” investor.” I checked my gut with a survey. The survey’s first question asked, “Which of the following is correct? They differ in hyphenation.”

The results? A tie between “high net worth investor” and “high-net-worth investor.”

Here’s what some fans of the unhyphenated “high net worth” said.

“Using two hyphens in a three-word modifier feels like overdoing it.”

“I just don’t like to hyphenate.”

“The phrase is clear without hyphens. Why clutter the page?”

The anti-clutter commenter mentioned The Associated Press Style Book, which says:

Use of the hyphen is far from standardized. It is optional in most cases, a matter of taste, judgment and style sense. But the fewer hyphens the better; use them only when not using them causes confusion.

Avoiding confusion is one reason that some readers favored hyphenation. They wanted to ensure that no one thinks the investors are high on drugs instead of net worth. “You need two hyphens to make things crystal clear,” said one respondent. I agree. I see high-net-worth as a compound modifier.

I don’t always hyphenate compound modifiers. When in doubt, I look at how respected sources, such as The Wall Street Journal handle the term. It hyphenates “high-net-worth investor,”as you can see in “Voices: Joshua Coleman, on Using a ‘Quarterback’ to Serve High-Net-Worth Clients.”

Whether you hyphenate or not, please pick one style and stick to it.

“High net worth” and your prospects

High net worth (HNW) is a useful term for discussions among financial professionals. But, when your prospects read “high net worth” do they think, “Yes, that’s me”?

The people whom you see as HNW may not agree. They may see themselves as middle class according to “Who You Calling Affluent?”, a study by CEB Global. (By the way, I typed the study title accurately. I checked multiple times to make sure that there was no “are” in it.)

The study says:

Only about 20% of the consumers we identified as affluent ($100K+ HHI and/or $100K+ in investible assets) considered themselves, or their income brackets, to be affluent. Even more surprising, more than half of consumers with household income above $500K per year or more than $5 million in investible assets don’t accept the “affluent” moniker, revealing a true discomfort with the term.

Before I found this CEB study, I polled my readers, asking “What’s the best way to refer to your target audience in marketing materials aimed at investors who have a high net worth?”

Only 25% chose “HNW.” “Affluent investors” was the most popular choice.

In favor of HNW, here’s what one person said, “Per my advisor friend: ‘Wealthy or affluent. It’s subjective but people with wealth are aware that they have it. HNW is an industry term that makes them feel like a trophy. Generally I find people start considering themselves wealthy when they have 1-2 million of investable assets, 5 million+ in real estate, or a 10 million+ operating company.’”

More commenters favoring HNW said

“Everything else is gauche, especially since we’re in such a polarized climate in terms of income inequality.”

“I don’t think people like to think of themselves as affluent or wealthy.”

Another person who favored “affluent” commented that the term “throws a big net.” That’s an interesting point. Among some audiences, “affluent” refers to investors one rung below HNW. According to one definition, “affluent” ranges from $100,000 to $1 million in investable assets. HNW starts at $1 million, according to this example.

A respondent who voted for “Investors with more than $__ to invest” said, “Nobody likes to be labeled. A dollar figure gets straight to the point and is completely objective.” Identifying specific dollar levels was much less popular than using a broad label. However, I was interested to see that a 2015 ad by Bessemer Trust stated “Minimum relationship $10 million.” It seems as if most firms targeting individuals or families are vague about how rich their new clients must be. Perhaps specificity gets easier as your minimum account size rises and it becomes more important to screen out prospects with insufficient assets.

Another respondent suggested using the term “individual investors as opposed to institutional.”

Personally, I’m not wild about using labels such as HNW outside our industry. I liked this respondent’s answer, “I don’t usually refer to their net worth. I focus on where they are in their financial life: nearing retirement.”

Thank you, respondents!

I’m grateful to everyone who answered my questions and shared their thoughtful comments. Thank you!

The post “High net worth” in your financial marketing appeared first on Susan Weiner's Blog on Investment Writing.

November 24, 2015

Writing tip: Kill the ST words!

Looking for an easy tweak to simplify your firm’s writing? If your audience is American, stop using three prepositions: “amidst,” “amongst,” and “whilst.” Substitute “amid,” “among,” and while.”

Why bother making such a small change?

It will speed your reader’s progress through your writing. These words ending in -st are viewed as archaic in American English, says Bryan Garner in Garner’s American English. Amongst, for example, “is pretentious at best,” writes Garner.

Don’t distract your readers with archaic or pretentious words. However, if you’re writing for a British audience, consult a British style guide. Don’t push American style on your British readers, unless that style is part of your appeal.

The post Writing tip: Kill the ST words! appeared first on Susan Weiner's Blog on Investment Writing.

November 17, 2015

Improve your speeches and deepen your family ties

Want to improve the expressiveness of your voice when you speak? Try the technique that my speaking coach taught me. It livened up my speeches. Plus, an unexpected benefit was that my twist on her technique also deepened my relationship with my husband.

Read children’s books to improve your speeches

Ozma of Oz sent me on the path to better speaking. That’s the first book I borrowed from the library after I got my coach’s advice.

Ozma of Oz sent me on the path to better speaking. That’s the first book I borrowed from the library after I got my coach’s advice.

Her advice? Read children’s books out loud with exaggerated expression. Somehow it’s easier to speak in an extreme way when imagining a little kid listening. Plus, it’s more fun to ham it up with “You’re in a pretty fix, Dorothy Gale, I can tell you!” than with a dry statement about asset allocation or financial planning.

“Practice makes perfect,” as they say. My expressiveness grew with this technique. Of course, there was still room for improvement. But I wasn’t going to make Oz books a staple of my reading. What to do?

Read newspapers to improve your speeches and your relationships

I had an inspiration. While on a longish car ride to a bicycle trail, I asked my husband, “Can I read articles from the newspaper’s travel section to you?” We both love to travel, but my husband often doesn’t get through the entire travel section.

It’s a win-win. I practice my vocal expression; my husband absorbs travel stories he might otherwise miss. Also, it keeps the two of us talking when I might otherwise read a book.

YOUR speaking tips?

If you have tips for improving one’s speaking skills, please share. I enjoy learning from you.

By the way, if you’re looking for a speaking coach, I highly recommend Cheryl Dolan.

Disclosure: If you click on the Amazon link in this post and then buy something, I will receive a small commission. I only link to books in which I find some value for my blog’s readers.

The post Improve your speeches and deepen your family ties appeared first on Susan Weiner's Blog on Investment Writing.

November 10, 2015

Investment commentary numbers: How to get them right

Investment commentary calls for lots of numbers: benchmark and portfolio returns, economic data, and more. When you get those numbers wrong, you undercut your credibility and embarrass yourself.

I have some ideas about how you can avoid mistakes by proofreading and checking your facts.

My expensive mistake

A bad experience impressed me with the importance of checking numbers. Reading the professionally printed copy of my employer’s third-quarter commentary, I noticed a goof. It referred to the second quarter, instead of the third quarter, in one spot. This happened even though four of us had read the piece before it went to the printer. However, the eye tends to read what it expects to see. We all glossed over my error. Oops!

That was an expensive mistake because we had to get the piece reprinted. However, at least we avoided the embarrassment of clients seeing our mistake. Also, it spurred me to develop techniques for catching numerical errors.

Tip 1. Add numbers to your checklist

Checklists, which I recommend in “5 proofreading tips for quarterly investment reports,” can help you catch numerical errors. For a typical quarterly investment publication, I’d add two kinds of numerical items to remind you to check for accuracy and timeliness.

Calendar information—record the current year, quarter, and ending date for the quarter. I don’t know about you but I sometimes can’t remember how many days there are in June so it’s handy to know that I should write about “the period ended June 30.”

Major index returns for the relevant periods—if you’re writing about multiple investment styles and periods, you’ll use multiple index returns. If possible, run a report that shows only the relevant returns and displays them in a logical order. If you lack the access to run or customize reports, create your own list and proofread it carefully.

After you’ve completed your writing, make one pass through your document to check that you’ve used the right calendar information and returns.

Tip 2. Standardize your sources for index returns

If you’re new to writing about investments, you might think, “The S&P 500 Index return for the fourth quarter is the S&P 500 Index return for the fourth quarter.” Uh uh. There’s not just one number. For example, the return number that comes directly from Standard & Poor’s may diverge from the number spit out by your firm’s performance measurement system. Which will you use?

Your firm needs to decide which are the official sources for index returns. And then, stick with using those sources. By the way, it’s also good to create a rule for how many places to the right of the decimal point you’ll go in reporting returns.

You should create similar rules for reporting portfolio returns, too.

Tip 3. Document sources for other numbers

What about sources for other numbers? Document those as you write.

Footnotes can track your sources. Insert a footnote with your data source. Insert a link to the data if one if available. It’ll make fact-checking easier later on.

Tip 4. Use a fact-checker

Just as it’s hard for you to proofread your own work, it’s hard for you to fact-check it. You’ll tend to see what you expect to see.

If you have an employee, colleague, or friend who can help, ask that person to compare every number to its approved source. Being unfamiliar with numbers, they’re more likely to pick up on mistakes.

Don’t have a helper? Fact-checking will still catch some errors. I know it works for me, especially if I concentrate solely on fact-checking in one pass through my document.

Tip 5. Catch contradictory numbers with informed readers

How can you catch two authors using contradictory numbers? Say, for example, one author says U.S. economic growth was 2.2% while another says it was 2.5%. Both provide a source for their numbers, as suggested in Tip 3, but they don’t match. If you’re lucky, your fact checker will catch the disparity. But you can’t count on it.

There’s a higher chance of catching the error if you have the two authors with overlapping topics read each other’s articles. Ask them to look for inconsistencies. Another approach is to get a third party to look for inconsistencies. You might even ask them to list all of the document’s numbers from non-standardized sources. That would make it easier to see that there are multiple sources for a single number. All of this takes a lot of time.

There’s no easy way to catch these contradictory numbers. If you have ideas about how to solve this problem, I’d like to hear from you.

Image courtesy of Stuart Miles at FreeDigitalPhotos.net

The post Investment commentary numbers: How to get them right appeared first on Susan Weiner's Blog on Investment Writing.

November 3, 2015

3 ways to make your emails mobile-friendly

Mobile-friendly emails are essential. Your clients, prospects, referral sources, and colleagues are increasingly reading emails on their mobile devices. If they don’t like what they see, they may delete or ignore your messages.

Here’s an interesting statistic from a webinar on “Demystifying Brand Journalism,” sponsored by the American Society of Business Press Editors:

80% of people delete an email if it doesn’t look good on their device.

I’m not a mobile guru, but I’ve noticed three things that encourage me to read emails on my phone.

Technique 1: Short subject lines that get to the point

No matter where your recipients read your emails, you’ll benefit from short subject lines that get to the point quickly. Your first two words are key, as I’ve said in “Improve your email subject-line vocabulary with The Hamster Revolution.”

“Short and sweet” is even more important on mobile devices, which may show as few as 15 characters of your subject line vs. 40+ characters on a traditional computer. Wearable devices could make things even tougher, as explained in “What effect could wearables have on email marketing?” by Wynn Zhou on memeburn.

Technique 2: Use mobile-friendly formatting

Traditional emails, especially multi-column e-newsletters, may be too wide to display well on mobile device. Below is an example of an image that’s too big to be mobile-friendly.

Example of an image that’s too big to be mobile-friendly

I believe that traditional text-only emails will fit well on your mobile device, although you should still do your best to make your email short and easily skimmed.

If you’ve been producing an e-newsletter for a long time, check to see if you can switch to a mobile-friendly or mobile-responsive format. I made the change earlier this year, using a template provided by Constant Contact.

Technique 3: Avoid attachments

Attachments and mobile devices don’t play well together. Attachments are a pain to download and even more of a pain to read on a tiny screen.

Want to share information beyond what’s in your email? Use a link to a mobile-friendly webpage.

YOUR suggestions?

What works to entice you to read emails on your phone? Much of what works on mobile devices also works on traditional computers.

Please share your insights. I enjoy learning from you.

The post 3 ways to make your emails mobile-friendly appeared first on Susan Weiner's Blog on Investment Writing.

October 27, 2015

Donald Trump, grade level, and your financial writing

Donald Trump’s appeal has surprised many observers of presidential elections. Love him or hate him, you can’t ignore his presence. Part of his appeal rests on his use of plain language, according to a recent article. That’s something financial professionals should note because of its implications for your writing.

Trump speaks at a fourth-grade level, according to “For presidential hopefuls, simpler language resonates,” which appeared in The Boston Globe. The newspaper calculated the grade level of presidential candidates’ announcement speeches. Lower grade levels use fewer characters and syllables per word, as well as shorter sentence lengths.

Simpler language wins

“Simpler language resonates with a broader swath of voters in an era of 140-character Twitter tweets and 10-second television sound bites, say specialists on political speech,” according to the article.

Trump’s language hit the lowest level of the 19 presidential announcement speeches analyzed for the article. After Trump, the next simplest were John Kasich at grade level 4.7 and Ben Carson at 5.9. On the Democratic side, Hillary Clinton and Martin O’Malley hit the lowest grade level for their party. They tied at 7.7.

Is it a coincidence that the presidential front runners have among the lowest grade levels for their parties? Perhaps not.

Less tolerance for higher grade levels

Political speeches of the past hit higher grade levels. Here are the levels of some presidential speeches, according to The Boston Globe:

17.9 for President George Washington’s “Farewell Address”

13.9 for President John F. Kennedy’s 1961 “State of the Union”

11 for President Abraham Lincoln’s “Gettysburg Address”

I believe that readers are generally less patient with wordiness than they were even five years ago. I know I am.

Message for financial professionals

What does this mean for you as a financial professional who writes? If you want to attract and retain readers, lower the grade level of your writing.

I’m not suggesting that you aim to write at a fourth-grade level, although that might work for a blog post on a basic topic. I do suggest that you become more aware of your output’s grade level and work to boost the ease with which readers can grasp your message.

Try this exercise: Calculate your grade level. You can find it using Microsoft Word’s readability statistics or the website I discuss in “Free help for wordy writers!” Then, try to lower your writing’s level by two grades.

If you can delete some unnecessary words or break a long sentence into two, you’ll have made progress.

Many financial communications exceed grade 12. That may be too high for audiences with short attention spans. However, you may find it hard to hit the direct marketers’ idea of eighth grade or lower.

When you write about complex topics, sometimes longer sentences are easier to understand than short sentences. Lower grade levels may also sacrifice nuances—or fail to satisfy your compliance officer. While I often hit an eighth-grade level on this blog, I am happy when I get my clients’ work down to a tenth-grade level. Even that isn’t always possible. Still, I do my best to make even technical topics relatively easy to understand.

You may think my advice doesn’t apply to you. You may figure that institutional clients or smart people will plow through whatever you write. I disagree. No one ever says, “Please rewrite this in a hard-to-understand style.”

Don’t know where to start in simplifying your writing? Hire me to coach you or to train your employees or professional society members.

Photo credit: Gage Skidmore CC BY-SA 3.0

The post Donald Trump, grade level, and your financial writing appeared first on Susan Weiner's Blog on Investment Writing.

October 20, 2015

Hey, loser, quit @ naming people to promote yourself

I enjoy exchanging tweets with people. I’ve made friends and learned things from these exchanges. But I get annoyed when people repeatedly tweet at me only to promote themselves and content that they’ve written.

Here’s an example of what I dislike:

Hey @susanweiner, read our great blog post at http://…

Their using my Twitter name—my @name, @susanweiner—forces their tweet to my attention. I hate this. Well, I’m exaggerating a bit, but I think you’ll know what I mean if you spend a lot of time on Twitter. When I look at these people’s Twitter timelines, they are filled with promotional tweets that differ only in the person whose Twitter name is mentioned.

I can forgive—and perhaps even enjoy—a one-time promotional tweet directed to @susanweiner. Perhaps there’s a link with some great content that’s perfect for me. But repeated tweets of the same self-promotional content that’s irrelevant to me? No, thanks.

This doesn’t mean that I’m against using Twitter to promote yourself. I do it all the time. However, I recommend that you tread lightly in @naming specific people if you’re not sure they’ll welcome your attention.

Thank you for @naming me in other cases

After I published this rant, I realized that I might scare those of you who use other people’s Twitter names in a good way.

Let me clarify. It is perfectly fine—and even desirable—for you to use a person’s Twitter name when you share something they’ve written or shared. It’s polite to give credit to people. I appreciate the many courteous people who do this for me.

Note: This post was updated and expanded on Oct. 30, 2015.

The post Hey, loser, quit @ naming people to promote yourself appeared first on Susan Weiner's Blog on Investment Writing.

Hey, loser, quit @naming people to promote yourself

I enjoy exchanging tweets with people. I’ve made friends and learned things from these exchanges. But I get annoyed when people repeatedly tweet at me only to promote themselves.

Here’s an example of what I dislike:

Hey @susanweiner, read our great blog post at http://…

Their using my Twitter name—my @name, @susanweiner—forces their tweet to my attention. I hate this. Well, I’m exaggerating a bit, but I think you’ll know what I mean if you spend a lot of time on Twitter. When I look at these people’s Twitter timelines, they are filled with promotional tweets that differ only in the person whose Twitter name is mentioned.

I can forgive—and perhaps even enjoy—a one-time promotional tweet directed to @susanweiner. Perhaps there’s a link with some great content that’s perfect for me. But repeated tweets of the same self-promotional content that’s irrelevant to me? No, thanks.

This doesn’t mean that I’m against using Twitter to promote yourself. I do it all the time. However, I recommend that you do tread lightly in @naming specific people if you’re not sure they’ll welcome your attention.

The post Hey, loser, quit @naming people to promote yourself appeared first on Susan Weiner's Blog on Investment Writing.

October 15, 2015

Top posts from the third quarter of 2015

Check out my top posts from the last quarter!

The top post targeted investment commentary writers. The other posts offered a mix of practical tips on writing (#3, 5, 10), blogging (#4, 7, 9), and email (#2, 6, 8).

Are financial predictions too risky for investment commentary writers?—this post sparked lots of discussion. Please join the conversation by leaving a comment or sharing on social media.

The email subject line you should never use

7 ways to manage writing by committee—read this if you’ve ever struggled with managing input from multiple people

Credit sources fairly in your financial blog posts—this is important if you want to be fair and avoid copyright infringement.

Financial writer’s clinic: fact vs. interpretation

What YOU say about highlighting text in emails

8 ways blogging is like bicycling

Email lesson from a PayPal co-founder

Use a wacky days list when you run out of blog ideas—I was surprised by this post’s popularity.

Don’t break up your text too much!

The post Top posts from the third quarter of 2015 appeared first on Susan Weiner's Blog on Investment Writing.

October 13, 2015

Portfolio performance commentary’s basic components

Commentary about portfolio performance is part of every investment manager’s communications. The depth and breadth of commentary varies widely. It can consist of a single line giving portfolio returns. Or, it can be a multi-page report full of charts, graphs, and details. The longest reports typically target institutional clients—not individuals.

In this article, I review portfolio performance reports’ common components.

1. Portfolio returns

Your portfolio’s results for at least one period are the sole essential element of portfolio performance reports. Portfolio returns are typically compared with the returns of one or more benchmarks to provide perspective on how the portfolio performed relative to its goals, investable universe, or peers. For mutual funds or ETFs, the main benchmark is specified in its prospectus. For separately managed accounts, the benchmark may be specified in the investment policy statement.

Showing multiple benchmarks can provide perspective on performance. Say, for example, you run a small-cap stock fund in the space between growth and blend. Showing returns for the Russell 3000 Growth and plain vanilla Russell 3000 indexes helps readers To understand the extent to which your portfolio’s less growth-oriented approach affected its performance.

Comparing your portfolios performance to its peers—say, Lipper Small-Cap Growth Funds if you run a mutual fund or its decile ranking in an applicable universe of institutional funds—also gives perspective. These comparisons may be more favorable than comparisons to indexes because these returns are measured net of expenses, unlike index returns, which have no expenses deducted. Peer groups may offer a more “real world” perspective on what managers can achieve.

Once you pick indexes for comparison, you must stick with them. You can’t decide, “we look good vs. Lipper this quarter, but bad vs. the S & P 500, so let’s only use Lipper this quarter.” The SEC doesn’t like that.

Similarly, you must be consistent in the periods of performance that you show. It’s a good idea to show more than one quarter of performance. You don’t want your clients to fixate on short-term performance. But once you start to show one-year, three-year, and since inception returns, you must continue to show them.

2. Attribution analysis

Can you attribute the portfolio’s performance to specific characteristics? That’s the question that attribution analysis seeks to answer.

Attribution analysis is typically measured by numbers. For example, “2.5% of the overall return came from stocks in the financials sector.”

Attribution may be considered relative to a benchmark or independently of benchmarks. When it’s measured relative to a benchmark, a key question is: Why did the portfolio outperform, underperform, or perform in line with the benchmark? You’ll look at factors such as the contributions of security selection, sector weightings, asset allocation, and maybe even cash positions and the flows of money into and out of the portfolio.

You can try to discuss portfolio performance independently of benchmarks. However, you may need to break with that policy if your performance dramatically diverges from the benchmark. This is especially true when you underperform. Your benchmark-savvy clients will want to know why you underperformed.

Numbers don’t tell the entire story of what drove performance. That’s why, at a minimum, someone directly involved in managing a portfolio should review its attribution commentary before publication.

3. Stock or sector stories

Stories about specific securities or sectors can shed light on how active managers think. Stories about winners—and losers—show what the fund managers emphasize in their decisions. Discussions of winners typically show off the managers’ strengths. They also display the managers’ understanding of the larger environment for investments. For example, they may speak to themes, such as beneficiaries of lower commodity prices, that the managers favor. They may also reflect the managers’ market outlooks.

Stories can also illuminate the performance of index funds, to the extent that they demonstrate how the market moves.

To keep the SEC happy, you can’t focus solely on winners, especially if your portfolio underperformed. You must balance your discussion—typically by discussing at least an equal number of losers, although you may have some leeway in a period when losers are hard to find.

Losers pose an extra challenge to writers. Should you defend your holding, in addition to explaining its performance? I like the consistency of keeping the format the same for both winners and losers. Plus, if you’re confined by tight word count limits, you can’t fully explain and defend. However, defensive comments help if you’re writing commentary for use by your firm’s client service team. They’ll thank you for making their job easier when clients question your holdings. Still, if you don’t explicitly defend your losers, you may provide some context in your market recap or market outlook sections.

4. Market recap

A market recap discusses recent market performance. It may focus narrowly on the portfolio’s asset class or it may range more broadly to provide context.

For example, a market recap for a U.S. high yield bond fund might discuss treasuries, investment-grade bonds, and riskier bonds to show how investors’ attitudes toward risk factored into the portfolio’s performance.

The goal of a market recap is to provide context for the portfolios’ performance. It may also provide insights into how the manager views markets.

5. Market outlook and portfolio positioning

Providing insights into the market’s future is the focus of the market outlook. Managers vary in their willingness to make predictions. Passive—AKA evidence-based—investment managers may shun predictions. However, for active managers, predictions help their investors to understand their portfolio positioning.

Comments on portfolio positioning complement market outlooks to the extent that the managers’ allocations to securities, sectors, and asset classes are driven by their market predictions. Of course, other factors affect positioning, such as the managers’ perception of long-term trends outside the markets—so-called secular themes—that will influence the performance of investments.

6. Top 10 holdings

Top 10 (or top five) holdings is a popular section on mutual fund fact sheets for the clues it offers into a fund’s composition, particularly when compared with its benchmark.

If you present to institutional clients, who tend to crave more detail than individual investors, you may write a brief description of your top holdings and why they’re in your portfolio.

7. Securities bought and sold

An asset manager’s buy-sell philosophy is important to investors as they evaluate placing their money with manager. Naturally, once they’re invested, they’d like to see how the manager implements that buy-sell philosophy.

Discussion of buys and sells isn’t part of every investment commentary. There simply isn’t room in some formats.

If you discuss your trades, don’t focus solely on your winners. As I said earlier, the SEC doesn’t like that. However, you can use objective criteria, such as every quarter discussing the three largest purchases and the three largest sales.

If you have enough room, give your readers a brief description of each company and why you bought or sold.

8. Graphs and charts

Some information is easier to absorb as a table, chart, or graph. Take advantage of these formats to help your readers. I particularly like graphs that show portfolio performance vs. a benchmark.

What did I miss?

Did I cover everything that you see as essential to investment commentary? Please share your opinions and insights.

The post Portfolio performance commentary’s basic components appeared first on Susan Weiner's Blog on Investment Writing.