Sandra Byrd's Blog, page 3

April 28, 2023

Ivy in the Walls

Photo used with purchase permission from Shutterstock.

Ever since reading the children’s book Madeline, I have been enchanted by the look of vines growing on a house. Vines make a house look sophisticated and beautiful, aristocratic somehow. When we moved into a new house with a broad face, I knew just how to accentuate that. Vines! I did some research and found the name of a vine I loved, one that was green in the summer and copper in autumn. Then I asked some friends, “Does anyone know anything about growing Virginia creeper?”

“Don’t do it!” most of them told me.“Yes, yes, beautiful—all right, we’ll give you that. But it is so invasive that you will never get it out once started. It not only grows along the face of your house, but in the cracks, under the siding (which loosens it up), and into the window casements (which makes them leak). You may pull, and you may spray, but once it’s there, it’s the owner, and you’re the tenant.”

So I changed my plans—no Virginia creeper. I’d known that it was strong—that a simple ivy could, over time, strangle a tree. I had not thought it was strong enough to rip my home apart. But it was.

Sin, it seems to me, works like that in our lives. It presents itself as something desirable and beautiful—or at the very least, harmless (Genesis 3:6). So I invite it in, welcoming whatever excitement it seems to bring my way—till it starts to wreak the havoc it always does ( James 1:15). If I catch it in time, I can rip it out before it does harm. But that’s not always possible. The best thing is not to plant it at all and avoid the pain it will most surely bring.

Purchase Dwell here: https://tinyurl.com/SandraByrdDwell

Taken from Dwell: 90 Days at Home with God by Sandra Byrd © 2023. Used by permission of Our Daily Bread Publishing®, Box 3566, Grand Rapids, MI 49501. All rights reserved. Further distribution is prohibited without written permission from Our Daily Bread Publishing (https://ourdailybreadpublishing.org/) ® at permissionsdept@odb.org.

A Time For Everything

Photo by Cole Keister on Unsplash

I was outside raking—which was hearty exercise, and actually felt good— in a warm hoodie and amongst cold breezes. The sky was bright blue; the leaves fluttering down were shades of wine and gold. It was kind of sad that they were at their most beautiful on their way to death. I picked one up. It had lost its pliable nature and was becoming stiff and crispy. And yet what a way to go out, in a blaze of glory, which most of us (though we are not leaves) might choose to do as well (Ecclesiastes 7:8).

The thought struck me: the tree must release that which is dead or dying to bring new life in a new season. I have held on to jobs for too long, past the time when I knew I could be serving better elsewhere. I’ve stayed in relationships out of nostalgia, even when they were no longer healthy. I’ve retained habits that weren’t working, and I have had to transition from mother of children to mother of adults, which is harder than it sounds. But without the ability and willingness to let go of that which has had its time (Philippians 3:13–14), I would not be able to make room for new people, new ministries, new phases—I’m a grandmother now!

Don’t be afraid to let go of something whose time has passed. It can go out in a blaze of beautiful glory, long remembered and treasured. Letting go makes way for new buds, shoots, flowers, and leaves. As something old passes and something new takes its place, the tree grows year by year. And so do we.

Purchase Dwell here: https://tinyurl.com/SandraByrdDwell

Taken from Dwell: 90 Days at Home with God by Sandra Byrd © 2023. Used by permission of Our Daily Bread Publishing®, Box 3566, Grand Rapids, MI 49501. All rights reserved. Further distribution is prohibited without written permission from Our Daily Bread Publishing (https://ourdailybreadpublishing.org) ® at permissionsdept@odb.org.

Night Lights

Photo used with purchase permission from Shutterstock.

I love night lights. I have one that looks like Marie Antoinette, the light streaming through her large bird’s-nest hairstyle. A sleek black-and- white Paris skyline night light graces my guest bathroom. I have tiny, pink track lights in my own bathroom, and under-the-counter lights shine softly in my kitchen. When my daughter moved into her own home, I bought her a night light with bright red poppies, which matched her style.

Night lights are sweet. They say, Here, don’t trip. Don’t be afraid. They give enough light to show you there is nothing to fear, but not so much as to startle you. Night lights are gentle and comforting, and they bring a bit of hope into dark places. When you wake up in the dark, they help orient and reassure. There’s a reason toy makers are now inserting night lights into stuffed animals; when little ones squeeze a bear or a baby doll, a bulb goes on, providing comfort and light at the same time.

We believers are night lights, too. We carry within us the greatest light the world has ever known, the one who created light and separated it from the darkness in a physical sense as well as in a spiritual, eternal sense. When we walk into a room, we dispel a little of the mist and fear by our presence and the presence of the one we carry with us (Matthew 5:14–16). We take the hands of those who don’t know the way and walk with them, so they don’t stumble, so they can see where they can safely walk. Our Light helps orient and reassure both us and those we come into contact with.

You may be a Marie Antoinette style, or you may be a poppy or a skyline or the world’s softest teddy bear that everyone wants to love on, and that’s okay. Your night light is just right no matter what it looks like.

Purchase Dwell here: https://tinyurl.com/SandraByrdDwell

Taken from Dwell: 90 Days at Home with God by Sandra Byrd © 2023. Used by permission of Our Daily Bread Publishing®, Box 3566, Grand Rapids, MI 49501. All rights reserved. Further distribution is prohibited without written permission from Our Daily Bread Publishing (https://ourdailybreadpublishing.org) ® at permissionsdept@odb.org.

March 13, 2023

Bread Basket

You know that old joke, “I know what to make for dinner: reservations”? Having someone else make the food, serve the food, and clean up after is an absolute dream.

Many of the restaurants we visit serve a little appetizer: maybe chips with salsa or a basket of bread with dipping oils. One favorite eatery serves hot rolls drenched in garlic butter. Or sometimes it’s biscuits with butter and jam or cornbread with honey. The best part? They’ll refill the bread basket as many times as you want. For free!

Therein lies the problem, and I’m not just talking carbs. The meal still lies ahead.

By the time the delicious dinner arrives, we’re full. We stick our forks in our entrees and take a few bites, but the food doesn’t taste as good as we remembered. The bread had seemed like a treat at the time, but because we ate so much of it, we have no room left for the nourishing parts of our meals.

This happens in our spiritual lives, too. We fill ourselves up on TV, movies, books, or social media, using up our time and even our daily dose of concentration. By the time we turn our attention to God’s Word—well, we’re stuffed! Instead of having a little of the bread and a lot of the meal, we eat a whole basket of garlic rolls, and there’s no room left for dinner.

Go ahead. Choose one biscuit: one TV show, something interesting on the Internet, or a few chapters of a great book. But be sure to save room for the main course every day (Psalm 119:103). I’m trying to consume less of the pre-meal entertainment so that I’ll still be hungry for the Word of God (Matthew 4:4).

February 14, 2023

The Six Queens of Henry VIII: Then and Now

© Royalty Now Studios

© Royalty Now Studios

© Royalty Now Studios

© Royalty Now Studios

© Royalty Now Studios

© Royalty Now Studios

When I was a young woman, I stumbled upon a 19th-century photo and remarked that, incredibly, the people then looked just like we do now, dressed differently. While that might seem like a blinding flash of the obvious, to history lovers used to seeing their favorites of centuries past in elaborate hairdos and sumptuous gowns, it’s grounding. I am proud to be a historical novelist, bringing the past to life, and I was awestruck with the graphic talents of a woman doing the same.

Becca Saladin Segovia said she started Royalty Now Studios, because, “similar to many people, I’m so intrigued by history, yet always felt separated from the figures. I always thought of history more like a movie than a series of real events… A favorite figure of mine is Anne Boleyn. For my first ever creation, I decided to give Anne a modern “upgrade” - hair that could break free from her headdress, a bit of makeup, a modern dress, and all of a sudden she looked lifelike. She looked like someone who could stand right in front of me and tell me her story from her own lips, instead of someone who is at the mercy of historians and Hollywood producers.

I create these images so we can learn about the past with a little more empathy for the figures involved. It seems to strike people somewhere visceral to look into the more relatable eyes of the famous figures we know and love.”

Please visit Becca’s Royalty Now Studios online!

Website: www.royaltynowstudios.com

Youtube: www.youtube.com/c/royaltynowstudios

January 27, 2023

English Ladies in Waiting

Anne Boleyn

Having close friends is an important part of most women's lives, from girlhood through womanhood. These friends might be especially valuable when the woman's position is exalted, public, and potentially treacherous - such friendships take on an even more critical role. When Oprah Winfrey started her empire, she brought along Gayle King. When Kate Middleton was preparing to become Catherine, Duchess of Cambridge, her sister Pippa was her constant companion. And when Anne Boleyn went to court to stay, she took her friends, too. Among them was her longtime friend, who would ultimately become her Chief Lady and Mistress of Robes, Meg Wyatt.

Ladies in waiting were companions at church, cards, dance, and hunt. They tended to their mistress when she was ill or anxious and shared her joys and pleasures. They did not do menial tasks - there were servants for that - but they remained in charge of essential elements of the Queen's household, such as her jewelry and wardrobe. They were gatekeepers; during the reign of Elizabeth I, small bribes were offered for access to Her Majesty. The Queen was expected to assist her maids of honor in becoming polished and finding a good match; they, in turn, were loyal, obedient, and ornaments of the court. Married women had more freedom, better rooms, and usually more contact with the Queen.

In her excellent book Ladies in Waiting, Anne Somerset quotes a lady-in-waiting to Queen Caroline, saying, "Courts are mysterious places ... Intrigues, jealousies, heart-burnings, lies, dissimulations thrive in (court) as mushrooms in a hot-bed." This is precisely the kind of place where one wants to know whom one can trust. Somerset tells us, "At a time when virtually every profession was an exclusively masculine preserve, the position of lady-in-waiting to the Queen was almost the only occupation that an upper-class Englishwoman could with propriety pursue." Although direct control was out of their hands, the power of influence, knowledge, gossip, and relationship networks was within the firm grasp of these ladies.

An appointment was not only by the personal choice of the King or Queen but was a political decision as well. Queen Victoria's first stand took place when her new Prime Minister, Robert Peel, meant to replace some of the ladies in her household to reflect the bipartisan English government and keep an equal political balance. According to Maureen Waller in Sovereign Ladies, Victoria was adamant. "'I cannot give up any of my ladies,' she told him at their second meeting. 'What ma'am!' Peel queried, 'Does Your Majesty mean to retain them all?' 'All,' she replied."

Queen Elizabeth I

Keeping a political balance was a concern during the Tudor years, too. Ladies from all the important households were appointed to be among the Queen's ladies, though she held her personal friends in the closest confidence. Queen Katherine of Aragon understandably preferred the ladies who had served her for most of her life until her death. Queen Anne Boleyn numbered both Wyatt sisters among her closest ladies, as well as Nan Zouche. Henry told his sixth wife, Queen Katherine Parr, that she may "choose whichever women she liked to pass the time with her in amusing manners or otherwise accompany her for her leisure."

Many Queens, like Elizabeth I, regularly surrounded themselves with family members, in her case, often those through her mother's side, hoping that they could trust in their loyalty and perhaps, like all of us, because they enjoyed the company of those they loved best.

Anne Boleyn portrait: English school, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Queen Elizabeth portrait: Walker Art Gallery, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Hever Castle, Childhood Home of Anne Boleyn

Sandra Byrd with Kate Eaton

Surrounded by a double moat, this historic castle began life as a lowly farmhouse on land awarded to Walter de Hevere by William the Conqueror in 1066. In 1270, Walter de Hevere’s grandson, William, built an impressive stone gatehouse and bailey on the site of the farmhouse. Tall, crenellated twin towers flanked the gatehouse, featuring cross-shaped arrow slits, a portcullis and a drawbridge to defend the castle. St. Peter’s Church at Hever is adjacent to the castle, and dates back more than eight hundred years.

The Boleyn connection to the castle began in 1459, when the property came into the hands of Geoffrey Bullen. Bullen was a wealthy mercer, or dealer in expensive fabrics, who became Lord Mayor of London the same year. His rise in prominence, first as an alderman and then as Lord Mayor, would have required Sir Geoffrey to maintain a home befitting his station. He was responsible for transforming the stone fortification into a comfortable and impressive Tudor dwelling for his family. Geoffrey Bullen’s son, William, inherited the castle from his father, and then in 1505 passed it down to his own son, Sir Thomas Boleyn.

Historians don’t agree on whether or not Anne Boleyn was born at Hever Castle, but it’s certain she lived at least part of her childhood there. It isn’t hard to imagine Anne and her siblings, Mary and George, running through the ancient bailey walls, strolling along the nearby River Eden and exploring the imposing twin towers. Most certainly, the sturdy walls of the castle’s Long Gallery were the site of many leave-takings as both Anne Boleyn and her sister, Mary, traveled back and forth from England to France. An interesting architectural note, common among the great homes of this era—the sisters’ bedrooms were actually quite small and cramped in comparison with Hever Castle’s public rooms.

There were no doubt dozens of servants in a house this size, not only to care for the Boleyns and their home, but also to attend to the large stables and expansive grounds at Hever Castle. The expectation that the Boleyn family would entertain traveling nobility expanded the household regularly. Henry VIII, himself, did eventually come to this castle in the English countryside. Under the bows of an ancient oak, King Henry made known his affection for the fascinating Anne Boleyn. He would visit Hever Castle several times during his pursuit of Anne. This lovely castle with a fascinating history remained in the Boleyn family until the death of Thomas Boleyn in 1539, at which time it reverted to the Crown. Hever was among the properties Henry awarded to his wife Anne of Cleves when he divorced her.

Resources:

http://www.timetravel-britain.com/articles/castles/hever.shtml

Photo credit: ID 2734347

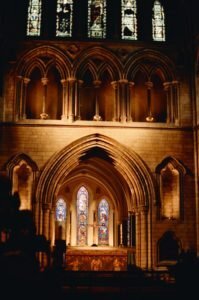

The Royal Road to the Church of England and Legitimacy of Elizabeth I

"It's notoriously difficult to pour a gallon of water into a pint pot," writes JRH Moorman in the preface to his excellent book, A History of the Church of England. For me, the task was to take what Moorman's poured into the pint pot and then spill that into a teaspoon. It's a challenge worth picking up, though one must overlook the summation of hundreds of years and many complex issues. To understand Tudor England, one must comprehend the religious and ruler-ship issues which shaped and informed Henry VIII's decision and authority to break with the Catholic Church and establish the Church of England and his nation's autonomy.

Origen writes of Britain as a place where Christians can be found as early as 240AD, and St. Patrick was famous for missionizing England from Ireland, but pick up the story in 1066 as the Normans invaded England. There was only one Christian church during this era, seated in Rome and headed by the Pope.

Moorman tells us that once he became king, William the Conqueror "...would not allow the pope to interfere with what he regarded as the king's lawful business...He (William) consequently made it clear from the start that he regarded himself as the head of the Church in England. He nominated the bishops and abbots and invested them with ring and staff. He summoned Church Councils. He expected his churchmen, just as much as his laymen, to respect his wishes, and he refused to allow any foreign interference with his sovereignty." This is a critical trail to follow one hundred years or so later to King Henry II.

The country had just undergone a punishing civil war whereby Henry's mother, Matilda, had tried to claim the throne of her father, Henry I, but Stephen of Blois, her cousin and also a grandchild of William I, had claimed it instead. Many noblemen, having come from France, where the Agnetic Succession laws forbid a woman from inheriting a throne, believed that a woman should not reign and blamed the unrest partially on a female claimant. Grateful for relative peace and calm, the nation hungered for stability after Stephen's death. Moorman reminds us that Henry II was "a wise and strong ruler determined to restore law and order." However, there remained a glitch.

Henry believed there must be one standard of law for all, rich or poor, lowborn or high, churchman or not, and he strove to set aside what was known as the "Benefit of Clergy." This benefit allowed any clergy member to be punished by church courts, where he might receive no punishment at all for crimes, including murder and rape. Sometimes the only test of the clergy was to have one's hair shaved into a tonsure, which Moorman says many non-clergy members did to escape civil justice.

Henry wanted justice to be fully invested in the civil law of the land, not of the church: all Englishmen, regardless of station or position, should be ruled by English law. The church, including Henry's very good friend Archbishop Thomas Becket, disagreed and stood in the way of this reform. Some years later, Henry II moaned something along the (apocryphal) lines of, "Can no one rid me of this meddlesome priest?" Four men took him seriously and murdered Becket in the Cathedral at Canterbury. The world was shocked, and Henry II never regained his moral authority. There was some merit to his concerns, though. Is the King truly the ruler over all England and Englishmen? Moorman tells us, " For over three hundred years, the shrine of St. Thomas at Canterbury stood as a witness to the triumph of Church over State. It was no wonder, therefore, that in 1538 Henry VIII took steps to have it destroyed and the martyr's bones scattered."

Although there was some movement toward church reform via Wycliffe and his followers, the Lollards, for the most part, the ruling classes of England stayed faithful to the Catholic Church right up till Henry VIII in the sixteenth century. Henry, a handsome, jovial, and learned king, was used to getting his own way. He was also used to having lots of money—his father, a notorious pinch-penny, left Henry a flush kingdom. He was a staunch supporter of Catholicism in the face of calls for church reform from people such as Martin Luther. In fact, the Pope awarded Henry the title "Defender of the Faith," a title which the crowned head of England still claims through Anglicanism. But regardless of everything obtained, he did not have the one thing he most wanted: a legitimate son.

The question has long been posed: Would Henry have set aside Katherine of Aragon and broken with the church if he’d had a lawful son? The simple fact is he didn't have one. He felt he needed one—remember the civil war that had rent England during the turmoil between Matilda and Steven? The Wars of the Roses had just been "solved," and Henry meant to keep the peace ... and the Tudor line ... going. When the Pope refused to allow him to dissolve his marriage to Queen Katherine, Henry's advisers gave him several assists. They reminded him of the passage in Leviticus, which claimed a man should not lie with his brother's wife (Henry had married his brother's widow). They also helped him reconsider who was the final authority in England: Pope or King?

Parliament eventually passed several acts separating England from Rome, including the Act in Restraint of Appeals, which asserts that "this realm of England is an empire and the king is the supreme head of both Church and State." Doing so provided Henry the legal and religious right to govern his own people without their ability to seek recourse from a foreign entity (the Church in Rome), dissolve his marriage to Katherine and marry Anne Boleyn, and have sovereignty over the properties in England, including the Dissolution of the Monasteries. He got the money (from the church properties he'd claimed), the girl, and was the Supreme Governor of the Church of England. One thing he didn't get—a son. Instead, an "s" was hastily added to the announcement of the arrival of a Princess, not a Prince.

However, those parliamentary acts allowed Queen Elizabeth I, the longest reigning and most important of Henry's children, to have unshakable civil legitimacy, if not in the eyes of the Catholic Church. All of Henry's wives from Anne Boleyn on were what we would now refer to as Protestant. But it would be Elizabeth who would firmly establish the Church of England: an excellent queen, to be sure, and perhaps the world's first female head of a Church. A Tudor.

{Main photo credit: By Peter of Langtoft - http://www.traditioninaction.org/SOD/SODimages3/108_BecketHenryII.jpg; original held in British Library, Royal 20 A II folio., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=5495869

{Photo of stained glass window: Photo by Christian Bowen on Unsplash }

{Photo of Elizabeth I: Workshop of Nicholas Hilliard [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons, Scanned from Jane Ashelford, The Art of Dress, London, National Trust, 1996, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4658944}

See No Evil, Hear No Evil, Speak No Evil

Eavesdroppers at Hampton Court Palace

Henry VIII had a famously acquisitive nature – and it wasn't limited to women. The man also had a passion for real estate. As king, he inherited many castles and palaces owned by the crown, but throughout his reign, he added others by purchase, trade, or payment of a debt; through reclamation to the crown due to attainder; "recovering" property through the dissolution of assets formerly owned by the Roman Catholic church; and by "gift." A primary advisor in the early years of Henry's sovereignty was Cardinal Thomas Wolsey, a man with tastes as extravagant as the King's and who also had the means to indulge them. When the King saw Hampton Court Palace, Cardinal Wolsey’s sumptuous, Thames-side property, he envied him it. Knowing that he was on uncertain terms with the king, Wolsey offered Hampton Court Palace to him. Henry accepted the generous gift but did not reinstate Wolsey in his favor.

Once he owned the palace, Henry set about remodeling. One of the most beautiful reconstructions was the Great Hall. The Great Hall was a large chamber where the king dined in public and where entertainments were often held. Like everything else in Henry's court, the hall was to be well-appointed to represent his power and glory. Historian Neville Williams claimed that masons worked round the clock for five years to complete the rebuilding of the hall to Henry's showy satisfaction. The room would have been overpowering to the senses, the tastes and smells of rich foods and spices, the feel of lush wood paneling and tightly woven tapestries, the music of players, the courtly flirtations. But high above the heads of the guests, tucked into the dark corners of the roof beams, lurked one of the Great Hall's most interesting features of all.

Delicate embellishments had been carved into the ceiling beams, among them an HA crest for Henry and Anne Boleyn, which remains to this day, but especially intriguing are the Eavesdroppers. The word eavesdropper has been in circulation since at least the 900s, coming from the old English, yfesdrype. It meant then just what it means now - someone listening to conversations in secret, watching and hearing without the permission or knowledge of the speakers. The cherubic courtier faces would have smiled down upon guests, reminding all that Henry was aware of everything at his court through courtiers and servants. Even while at play, there was never a time for loose tongues among long ears, as those who spoke freely often did to perilous consequences. At the Tudor Court, it was better to see nothing, hear nothing, and say nothing till you were in private chambers where eavesdroppers, one hoped, did not lurk.

Eavesdropper photo copyright Helen Newall, http://tinyurl.com/hcpeavesdroppers

Entwined HA on HCP ceiling photo copyright Felicity Boardman

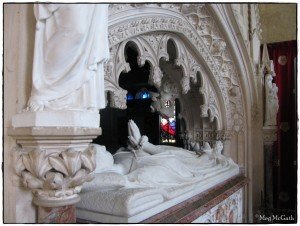

Mother Mourning: Childbed Fever in Tudor Times

Black death. The Great Pestilence. Plague. Sweating Sickness. The very words themselves cause us to shudder, and they certainly caused those in centuries past to quake because they and their loved ones were often afflicted by those diseases. But when we survey the physical ailments that afflicted sixteenth century women there is one death that caused the deepest fear among women: Childbed Fever, also known as Puerperal Fever and later called The Doctors' Plague.

Medieval and Tudor medicine centered around both astrology and the common belief that all health and illness was contained in balance or imbalance of the four "humours" of bodily fluids: blood, black bile, yellow bile and phlegm. Therefore, the letting of blood or sniffing of urine were common manners to address or diagnose illness. Although it seems ludicrous to us today, this understanding of medicine had reigned supreme for nearly 2000 years, coming down from Greek and Roman philosophical systems. It's been said that perhaps only 10-15% of those living in the Tudor era made it past their fortieth birthday. Common causes of illness leading to death? Lack of hygiene and sanitation.

Elizabeth of York

Decades before the germ theory was validated in the late nineteenth century, Hungarian physician Ignac Semmelweis noticed that women who gave birth at home had a lower incidence of childbed fever than those who gave birth in hospitals. Statistics showed, "Between 1831 and 1843, only 10 mothers per 10,000 died of puerperal fever when delivered at home ... while 600 per 10,000 died on the wards of the city's General Lying In Hospital."[1] Higher-born women, those with access to expensive doctors, suffered from childbed fever more frequently than those attended by midwives who saw fewer patients and not usually one after another.

In 1795 Dr. Alexander Gordon wrote, "It is a disagreeable declaration for me to mention that I myself was the means of carrying the infection to a great number of women."[2] Although they did not realize it at the time, it was, in fact, the sixteenth-century doctors themselves who were transmitting death and disease to delivering mothers because the doctors did not disinfect their hands or tools, in-between patients.

Queen Jane Seymour

Because illnesses are often transmitted via germs, doctors (and busy midwives) could infect young mothers one after another, most often with what is now known as staph or strep infection in the uterine lining. Semmelweis discovered that using an antiseptic wash before assisting in the delivery of the mother cut the incidence of Childbed Fever by at least 90% and perhaps as much as 99%, but his findings were soundly rejected. Infected women had no antibiotics to stop the onslaught of familiar symptoms once they began: fever, chills, flu-like symptoms, a terrible headache, foul discharge, distended abdomen, and occasionally, loss of sanity just before death.

Katherine Parr

This kind of death was no respecter of persons, as mentioned above, it perhaps struck the highborn more frequently than the lowborn. In fact, fear of childbed fever is often mentioned when discussing Elizabeth I's reluctance to marry and bear children. In the Tudor era Elizabeth of York, the mother of Henry VIII, died of Childbed Fever, as did two of Henry's wives: Queen Jane Seymour and Queen Katherine Parr, though her child was fathered by her fourth husband, Thomas Seymour. Parr's deathbed scene is perhaps one of the most chilling death accounts of the century, beheadings included.

Although Semmelweis was outcast from the community of physicians for his implication that they themselves were the transmitters of disease, ultimately, science and modern medicine prevailed. Today, in the developed world, few of the newly delivered die due to Puerperal Fever. Moms no longer need fear that the very act of bringing forth life will ultimately cause their own deaths and, therefore, can happily bond with their babies instead.

[1]

The Doctors' Plague: Germs, Childbed Fever, and the Strange Story of Ignac Semmelweis, Sherwin B Nuland, WW Norton, 2004

[2]

Oliver Wendell Homes: The Contagiousness of Puerperal Fever

{Main photo credit: Copyright Meg McGath, used with permission.}

{ Jane Seymour photo credit: Queen Jane Seymour, courtesy of Wikimedia. By Hans Holbein - egE1bExAbnBDgg at Google Cultural Institute maximum zoom level, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=22189674 }

{ Elizabeth of York photo credit: By Elizabeth_and_Henry.jpg: Malden, Sarah, Countess of Essex (c. 1761-1838)[1][2] derivative work: Jappalang (Elizabeth_and_Henry.jpg) [Public domain or Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=6859938 }

{Katherine Parr photo credit: After Master John, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Fi...}