Jacob Bacharach's Blog, page 23

May 17, 2014

A Sulz on Women

A few brief thoughts on the New York Times-Sulzberger-Abramson affair.

It’s awfully difficult to feel badly for income discrepancies where people are making hundreds upon hundreds of thousands of dollars. Beyond a certain income level, which I would set at significantly less than $100,000 per year, it’s all just surplus value; its only purpose—if that word applies—is luxury purchasing for purposes of status signaling. This is not to say that women executives should be paid less than their immediate male counterparts; rather, no one should be paid so much money to be a general manager.

In any case, the focus on corporate income inequality between men and women is a classic example of mistaking a symptom for a syndrome. Women are not paid less than men—whether in the executive office or at the greeters line in WalMart—because late capitalism is malfunctioning, but rather because that is a function of capitalism. Yes, women’s inequality long predates the modern economy, but the systems of capitalism incorporate preexisting forms of social and material inequality to their own end. A great deal of time and attention and political will is about to be frittered away “addressing the growing concern” over income inequality in the nation’s corporate media. Meanwhile, the question of what it means to have the nation’s singular newspaper a publicly traded corporate entity and the nation’s media in general an elite enterprise accessible as an occupation almost solely to those whose families have the previously acquired resources to support their effectively unpaid labor for as much as a decade will go largely unasked and entirely unanswered.

In other words, yes, it is a problem in a narrowly defined sense that a woman reporter for the Times is making eighty grand a year while her male colleague is making ninety-five, or what have you, but it is a problem in a much broader sense that she went to Bryn Mawr and he went to Brown and both of their New York rents were floated by their parents for 4-5 post-undergraduate years of internships and sub-$30K reporting gigs; that these two employees consider this a natural state of affairs; that their employer considers it so (obviously) as well. These are the people who report on “income inequality.” In a very circumscribed sense, they experienced and performed low-income labor—for them, a rite of passage, a way station.

Here is where the difference between the C-level and the checkout lane start to look a little more important. Let’s go back to that certain level of income. For all practical purposes, the difference between $400K and $500K—this is roughly the range we’re talking about for these Times editors—is meaningless. There is nothing of actual value that these people can’t buy; they can buy anything they reasonably want or need many times over. The idea that the arithmetical equality of dollars-per-annum for a bunch of rich people is a measure of anything beyond mere counting is the fundamental error here. What is at stake is a status claim.

Meanwhile, a representative sentence from The New York Times :

Republicans contended [that Seattle’s attempt to raise the minimum wage to $15/hour] would be a job-killer, while Democrats asserted it would help alleviate poverty. Economists said both might be right.

Wait, that isn’t fair! The Times has strongly editorialized in favor of raising the minimum wage!

Well, sure, but then again, a few months later.

Stop looking at the stories and start looking at the coverage. The narrative it builds is of a fraught and deeply technical political and economic question being argued passionately at the highest levels of government, in academia, and in the media—a debate mediated by and, in a perverse sense, for people who are making hundreds of thousands of dollars—the sort of people for whom there is something called “the economy.” “Both might be right”!

These are the sorts of ersatz and imponderable conversations that capitalism, personified by its functionaries, likes to have both with and about itself. Have you recently used the phrase “rising inequality.” Ding-ding-ding! You listen with some anguish to NPR pieces on the “growing gap between the rich and the poor.” You, like the Times, recognize that it’s impossible to live on the minimum wage alone, and that even $15/hour condemns a wage-earner to a life of struggle and fretting over the bills. But isn’t it true that mandated upward pressure on the low end of wages will force businesses to slow hiring? The unemployment rate is so high! We need more jobs! No, we need good jobs! Oh, woe, what is a “the economy” to do?

Pause. Here’s a question that you rarely hear anyone ask. What is money? I’ve always been very fond of the late author Iain M. Banks formulation in his first science fiction novel. Money is a “crude, over-complicated and inefficient form of rationing.”

Rationing! You mean, like communism?

Yes, Virginia.

Stay with me. In 2010, women comprised 47 percent of the total US Labor Force. Now, estimates differ, as the Times might say, but broadly speaking, women are assumed to make somewhere between 75-85% of what men make in, as the Times might say, broadly comparable positions.

Okay, I want you to imagine the Times, or any similar publication, publishing an editorial that says women should not make as much as men for the same work because of the fundamental damage that “some Republicans” or “some economists” say that “equal pay” would do to our old friend, the economy.

Because, after all, the cost of bringing the compensation of all women in the workforce into wage/salary parity with men would far exceed that of increasing the minimum wage—even dramatically—for the just several million people who earn it. So why, then, is the one a debate and the other a moral imperative?

I’m glad you asked! Capitalism is a system of surpluses, and it allocates them upward. It gives more rations to people who already have a pile. Should women make as much as men, blacks as much as whites? Yes. But these debates are moral proxies for debates that we are not having, at least, not in the pages of the Times. The answer to the question of whether a woman line worker should make as much as the guy next to her is yes. The answer to the question of whether Jill Abramson should have made as much as Bill Keller is smash the system of state capital and reallocate the surpluses in the form of lifetime guaranteed housing, clothing, food, and study for everyone. I am not being crass here. There is, quite literally, plenty to go around.

Yeah, well, how does this affect Hillary’s chances in 2016?

There is, of course, a corollary debate. This debate has to do with the question of why it is that women in leadership roles are pushy and opinionated while men are strong and decisive, or, well, you pick the opposing pairs of adjectives—why, in short, is the behavior of women judged on measures of temperament, and men’s on measures of will? It strikes me that the actual question being asked here is: why, upon achieving a position of dominance, aren’t women as free to act like monstrous dickheads as men? The management behaviors ascribed to both Abramson and her predecessors are the worst kind of B-school blowhard psychopathy: management based on fear; power maintained by its own inconsistent application. These sorts of hard-driven, hard-driving, chair-tossing, dressing-down applications of personal power within a rigid hierarchy of authority are, like that big ol’ salary, a kind of surplus; an excess; an overage. So the question can’t be: how do we permit a few more women to behave like the lunatic men who’ve been running the show all these years, but how do we prohibit or prevent anyone from acting this way? And here, too, the answer is a more fundamental sort of levelling, because the other option, which is the false promise of our society, is the belief that it is the duty of each person to scramble madly from the broad base toward the unattainable height, is a Sisyphean punishment where we all—well, most of us—under the weight of our own bodies are forever sent tumbling down the sides of the same brutal slope.

May 13, 2014

Theme: Amazing

Jim Jarmusch’s Only Lovers Left Alive opens with blood-red titles in a font I will call Third Reich Martin Luther Sans Serif against a very slowly rotating star field. The text is so remarkably crisp at the edge and the rotation so leisurely that the impression is of words floating out of a deep field into your eyeballs, the sort of three-dimensional effect that none of the bogus 3D efforts of the last several regrettable years in cinema history has managed to accomplish. The opening credits disappear. The stars revolve more quickly, resolving into a spinning short play record. The pace is—I use the word advisedly—majestic; it’s languorous. There’s a point to this. I’ll get there in a moment.

Spiderman The Amazing Man 5 opens with a scene from Television’s Revenge. The reboot has retooled/retconned Peter Parker’s father into a sort of whistleblowing scientist for the Oscorp corporate octopus whose various executives and research mishaps are the source of all woe in the Spideyverse. It isn’t an inherently bad idea, although it could have all been sketched with a few lines of dialogue rather than shot as a broadcast-quality teaser episode on a fake-looking Gulfstream set. It’s all loud, cheap, and makes very little sense. Cut to hectic scene of Spiderman doing his thing and Paul Giamatti getting, if not earning, a paycheck.

You might say it’s unfair to compare the films, because one is a zillion-dollar tentpole blockbuster and the other is a stately art flick. In fact, one of the things I like about Jarmush’s picture is that it really isn’t an art flick; if stylized, then it’s still a genre flick, full of plenty of fun tropes pulled from every other vampire movie ever, including some pretty hilarious digs at the old Interview with a Vampire rock star conceit. I mean that as a compliment. Even its goofy literary references are as clunky as you’d find in a costumed flashback on The Vampire Diaries. Ohhh, Byron. Ohhhh, Marlowe. I choose to believe this was intentional. The movie is slow and quiet, but never not trashy fun.

Look, really, I’m not going to go to the trouble of reviewing either film. I’m only interested in a particular and pretty technical comparison of how to render a particular aspect of sense and consciousness in a filmic medium, and what it is that this says about a good movie versus a bad. Both movies, you see, have to find solutions to the question of how to display, on a practical level, superhuman sensitivity and sensory perception. Marc Webb, of Spiderman, does this in the same rote and over-produced manner as every other action movie that’s contemplated the question in recent memory. He slows down the frame, then the not-actual digital eye of the non-camera moves through the rendered images to record all those things that Spidey would notice with his Spidey sense. Sometimes, zip-zoom-boom, the whole thing then re-transpires at normal speed. Yawn. Chewing sounds from the audience. The collection of red pixels that is the movie’s star bounces around some more.

In Only Lovers, by contrast, the whole affair is deliberate and slow—also, very quiet, other than the music. When the rare outside sound intrudes—a group of nosy fans outside Tom Hiddleston’s vampire dump, a soda can opening and cutting a man’s finger on a plane—it registers so deeply against the quiet, and so intensely on the faces of Hiddleston and Swinton, our vampire pair, that we in the audience experience it in the same three dimensions as we experience those red letters against that background of stars. If you think of those times when you’ve watched TV late at night—you can’t sleep, but as the hours tick till morning, you find that the volume becomes oppressively loud, so you turn it down, only to find a few minutes later that the feeling’s returned, so you turn it down again—you have some idea of the sensitivity this implies; the weird feeling of noting everything. The effect is subtle and clear, and it renders the characters as simultaneously supernatural and real.

Only Lovers is 120 slow minutes that seem to be over the moment they’ve begun; Spidercorps 2: Not Without My Aunt May is 140 fast minutes that seem interminable. These are both schlock films about mythological creatures, but one of them is good. Its director and its stars give us time to notice; noticing is engagement; engagement is participation; participation is enjoyment; enjoyment is joy, which is why we go to the goddman movies in the first place, no?

May 2, 2014

The Crimean Snore

“I’m not sure how many schools prepare students for this kind of love.”

Again this morning news out of Ukraine,

revanchist Russia shoots down helicopters

and NATO loads its fearsome teleprompters

—we’ve been here before—we’ll be here again.

The world is fucked, but in its rubble and pain

ordinary people find the time

for family, sex and music, petty crime

—for love and death and staying entertained.

There are great loves, and there are great books;

let’s not deny the world its poetry,

but let’s not pretend the world is aging past

some youth—passion moderated, looks

declining, romance gone, because some twee

old journalist got his divorce at last.

April 29, 2014

Is this Your Homework Larry?

Among a certain class of Americans, those of us who go to “good” colleges and take, sometime during our freshman and sophomore years, some sort of introduction to sociology course, there is the universal experience of that one student. He is inevitably, invariably male; he is either in or has recently completed a course in biology, although he is almost certainly not a biology major; he finds, in almost every class, an opportunity to loudly and circularly suppose that some or other human social phenomenon is a direct analogue of some behavior in ant colonies or beehives or schools of fish or herds of gazelles. Mine was a boy who, after a section on suicide clustering, suggested that it could be explained quite easily, really; certain ants, after all, when ill or infirm, remove themselves from the nest, lest they burden their kin. So all those kids in Jersey, they, like, you know, they like knew that they were going to, like, be, like, a burden, you know, to society, because they weren’t, you know, going to, like, be successful or whatever, so, you know, you know what I’m saying.

He’s not without his charms. If consciousness is a continuum, from bacterium to baccalaureate, rather than just some crowning and discrete achievement of a select and tiny sliver of the mammalian class, then surely animals have plenty to teach us about ourselves, and surely animal societies have plenty to teach us about our own. And likewise, while I like to believe that our lives and beings are something more than the dull, material expression of DNA, that biology is not, in fact, destiny, I know that this belief amounts to a kind of self-praise and willful self-regard. “Oh, honey, you are special.” I believe in free will and self-determination, but let’s just say I accept that they must be subject to some reasonable natural limits.

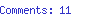

But now over at Vox.com, Ezra Klein’s intrepid effort to out-USA Today USA Today, Zach Beauchamp has discovered two political scientists who have discovered “circumstantial” evidence that human wars are the genetic remnant of animal territoriality. DNA is mentioned, but there are no double helices in sight; what’s meant is something more akin to the “animal spirits” that Tristram Shandy was so concerned with, or perhaps a kind of pre-genetic, crypto-Mendelian, semi-hemi-demi-Darwinian understanding of trait inheritance. In this case, the authors of a study, and the author of the article, notice that animals are territorial, that humans are territorial, that both come into intraspecies conflict over territory, and therefore, ergo, voilà. It has the remarkable distinction of being both self-evidently correct and skull-crushingly wrong. The deep roots of human territoriality are animal, but explaining organized human warfare in this manner has the motel smell of a husband telling his wife that he’s been fucking other women due to evolutionary mating imperatives. “Babe, calm down! Have you ever heard of bonobos, huh?”

Beauchamp treats territoriality among animals as an imponderable feature of “animal psychology”—he doesn’t mention, and you’ve got to assume he just doesn’t know, that the behaviors are largely about resource distribution, and, well, ya wonder if that’s got anything to do with warfare? Eh . . . He says that we “evolved from” animals, which is another one of those strictly true but effectively incorrect statements, a recapitulation of the old teleology that makes evolution a unidirectional progression from low to high, with humans not only its ultimate achievement but also its point. (He also—this is an aside—confuses accountancy and finance, claiming that a $100 real loss is identical to $100 in opportunity cost, all this by way of clumsily explaining loss aversion.) He uses the phrase “just a theory.” He gets to the end of the penultimate paragraph, then:

Toft and Johnson just don’t have any studies of human biology or evolution that directly show a biological impulse towards territoriality.

Phlogiston! God Bless You!

I’m not a religious man, but I empathize with the religious when they call this hooey scientism, the replacement of one set of hoary mythological clichés with their contemporary TED-talk equivalent—I mean, talk about inherited traits. If this kind of thing is science, then it is less Louis Pasteur than it is Aristotle, the general observation of a couple of different things with some shared trait or simultaneity, and then a vast leap of logic alone across the evidenceless abyss. The purpose of such speculation is not to clarify, illuminate, or discover, and Lord only knows, we wouldn’t want to waste our time devising some kind of double-blind. This, after all, is political science. Its purpose, rather, is moral flattery, an up-from-the-slime story in which our more regrettable and barbarous traits as people are written off as the bad debt of our evolutionary ancestors. And speaking of moral flattery, you might notice that “gang wars” are mentioned, and “ethnic” conflict, and Crimea in this great gallery of weeping over our remnant animalism, but nowhere is it explained how land tenure explains what America was doing, for example, in Iraq.

April 19, 2014

Mundus et Infans

“They were there for a discreet, invitation-only summit hosted by the Obama administration to find common ground between the public sector and the so-called next-generation philanthropists, many of whom stand to inherit billions in private wealth.”

If Piketty is to be believed

the rate of wealth accumulation, labeled

r, will in fact inevitably exceed

the rate of growth; thus are the rich enabled

to pass their filthy riches on to their

unencumbered offspring, whose vocation

is to be an unearned billionaire,

buying and spending unearned veneration.

Charity is fine. Philanthropy

is surplus value’s subtle marketing,

minor heat loss in the form of piety.

Yo, muse; shit’s fucked and bullshit; this I sing:

what is the point of having an election

when The New York Times has got a Styles section?

April 9, 2014

Sometimes You Eat the Bear and Sometimes the Bear Tortures, Rapes, and Murders Your Entire Family for No Particular Reason ¡Boobs!

Game of Thrones is supposed to belong to a post-Tolkienian form of fantasy that dispenses with the pewter trappings of the high-fantastic sword-and-sorcery formula, where, in Miéville’s game, funny description, “morality is absolute, and political complexities conveniently evaporate. Battles are glorious and death is noble. The good look the part, and the evil are ugly. Elves are natural aristos, hobbits are the salt of the earth, and – in a fairyland version of genetic determinism – orcs are shits by birth. This is a conservative hymn to order and reason – to the status quo.” The GoT series’ creator, George R.R. Martin, obviously and self-confessedly mined actual history as inspiration—he notably cites the War of the Roses as a source.

As literature, his writing is no better than Tolkien. If Tolkien is, per Miéville, “like opera without the music,” then Martin is Tom Clancy without the helicopters. Workmanlike would be too much praise by half. But, like Tolkien, Martin manages despite the sentence-by-sentence weakness of his work, to maintain an impressively consistent air. Tolkien’s was dread and doom; Martin’s is fear and gloom. To his credit, his most beautiful and noble (in the genealogical sense) characters are often the ugliest and most irredeemably evil and cruel. He is a misogynist, but his misogyny is at least in service of his deliberate atmosphere of unrelenting brutality, unlike Tolkien, whose Pre-Raphaelite maidens gaze virginally out of their frames while fey, faygeleh menfolk seem ever on the verge of the wrestling scene from Women in Love.

Martin’s fantasy world is distinguished by its impossibly long seasons, each lasting many years, and there’s at least some passing mention of storing up food for the long winter that approaches. HBO’s version effectively forgot about this peculiarity of its fictive setting once it killed off the majority of its Northerners—the nobly flawed Stark family’s motto (its “words”, in the in-universe terminology) were, in fact, “Winter Is Coming.” That’s fine. The show’s first season was pretty good TV, an improvement, if you ask me, over Martin’s turbid and overlong volumes, and it helped that it had a compelling central plot. Good art is frequently made not in spite of formal constraints, but because of them. Martin’s York-and-Lancaster framework keeps the story from wandering too far into the weeds. The bad guys, such as they are, win in the end, which subverts the genre but not the narrative; in fact, when the shock of it passes, it feels inevitable, which is a mark of good storytelling.

Subsequent seasons have dissipated into a series of parodically violent picaresques with occasional jump-cuts to various scenes of sub-Verdian scheming nobility. I’ll leave aside, for the moment, the white girl, her brown army, and her three dragons on the other side of the world. By its end, the third season resembled nothing so much as the Black Knight sequence from Monty Python and the Holy Grail, though carried off with such an air of dourly amoral self-seriousness that I half expected Kevin Spacey to stop into the capital’s whorehouse and mention his Congressional campaign. The level of violence is cartoonishly absurd; I mean, we are in, like, Itchy and Scratchy territory, here. At one point, a warrior woman fights a bear. It isn’t meant as a punch line, yuk-yuk, but it is.

Now, as we enter the fourth season, the overwhelming question is: how do these people eat? Fiction, of course, necessarily dispenses with plenty of fundamentals of actual existence in order to force life into its linear format, and no one, not even Houellebecq, wants to write a novel in which everyone spends all of their time opening doors, sleeping, pooping, and remembering that they need to buy mouthwash and paper towels on the way home. But the world of Game of Thrones is meant, despite its fantasy-genre affect, to feel lived-in and real. No one stops to wonder, amidst the depopulated and desolate marches of Middle Earth, how Rohan gets all that meat and mead, any more than they do in the middle of Beowulf, but it is impossible, as we wander into one more Westerosi tavern, rape all of the women, kill the cook, and burn down the village, just how on earth these people, from peasants to princes, manage to fill their bellies from time to time.

The portrait of feudal society as unremittingly violent and bleak, a never-ending, failed-state, crypto-Hobbesian war of all against all, is the really fantastical element of all this, far more so than a trio of squabbling adolescent dragons. This is not to say that Europe between Rome and the Enlightenment was a Hobbit-y idyll, verdant and free of war, plague, and exploitation. It was not. And yet, this fundamentally agrarian society lasted for a millennium, with the various forms of feudalism as social mechanisms for organizing productive land and the Church, for all its earthly corruptions and abuses, serving a complementary social organizing role. What is the manor, after all, if not a farm? Lords may have exploited their peasantry, overworked them, and taken too large a share of the crop, but they didn’t devote quite so much time and effort to randomly and wantonly terrorizing, raping, and murdering them, because, after all, who else is going to till the fields? Warfare in medieval Europe was limited due to primitive technology and low population, but also by the demands of the fields. It would not do to destroy all of the farms. The fundamental activity of this society was feeding itself, not, I don’t know, not mindlessly murdering everybody all the time in incoherent wars of dynastic succession. Game of Thrones makes the very worst excesses of the Crusades an hourly occurrence, an entire civilization an unrelenting, pre-mechanized Stalingrad.

The criticism of Game of Thrones—that it is a violent, sexist, rape-fantasy farrago whose fantastical-historical setting is little more than moral excuse-making for the fact that it wants naked women to beat each other with spiked clubs—is now wholly correct. The proof of this is in the fact that it has not the slightest interest in engaging with or depicting an actually realized world. How many times must it be said: realism is not the quality of set design. Nothing about this world makes any sense, unless the world is taken only as a convenient exercise in excuse-making for the dullest sort of murder-rape fantasy. Its setting is a moral excuse constructed solely to absolve viewers of their own interest in a pornography of sexualized bloodshed. Even a show as crassly, unnecessarily gory as The Walking Dead, for all its silliness and perversity, challenges its audience with some vague hint of complicity; there, but for the grace of the fact there is no such thing as a zombie apocalypse, go we. Game of Thrones just gives an otherworldly hall pass to our own unseemly tastes.

UPDATE: Commenter Patrick links a great post from cool Tumblr People of Color in European Art History that covers similar territory, and better.

April 4, 2014

The Daughters of Edward Darley Boit

Their peripatetic parents probably

assumed it was an ordinary life:

charming girlhood, and then someone’s wife,

pinafores for evening gowns, lives free

of want, although not literally free;

husbands living on the interest of

what their own fathers socked away, and love

a sickly symptom of maturity.

Adults, poor things, rarely can admit

even to themselves how clearly they remember

that kids don’t learn from parents; children carry

a whole soul as a completed secret,

its wholeness brief as daylight in November.

The daughters in the portrait do not marry.

March 14, 2014

Huginn and Muninn

My friend, whom I’ve never really met

asked if I’d write a poem on David Stove,

philosopher. I don’t know much about

him, although I’ve heard he didn’t like

blacks very much, or ladies, or ravens

or Kant or Platonists or much at all.

Now, philosophy isn’t all

bad; it has its uses. But have you met

a Platonist you’d watch a Steelers-Ravens

division game with? You’d want to stove

his head in before halftime, like

you know he’d be that guy who’s on about

the sublimated homo stuff. About

the third commercial break, third beer, we’d all

make our excuses. Look, no one likes

to think about their likes. I’ve met

enough philosophers to know that Stove

had a point about the paradox of ravens,

or at least about the guys who think that ravens

are of formal interest. Of course, the thing about

these birds is that they use tools, but Stove

thought sociobiology was all

—and a priori—crap, although it met

his preference for induction. He’s sort of like

that friend of yours who says he really likes

the outdoors but can’t tell hawks from ravens,

and brings back wet firewood, who met

the need to shit outside with a rant about

how man is not an animal. You all

wanted to roast him on the camp stove.

Now, this is not to shit on David Stove.

I’m a contrarian myself. I like

a scholar who thinks his discipline is all

or mostly bunk. But the truth about ravens

is not that they are black, but that about

when man un-animaled himself, he met

something like himself in the birds, he met

thought and mind; all fathers sat about

the winter stove, making myths of ravens.

March 12, 2014

Inferior Musicians Giving Great Pleasure to Themselves

HBO’s charming mid-aughts cosplay porno, Rome, habitually botched the broad canvas of history, but it did manage some excellent brush strokes, many of them dabbed around the series’ real star, Ian McNeice, who played the forum reader, a wonderfully amoral news anchor who stands in gorgeous fixity amid the whirl of war and upheaval, a pole whose flag is perfectly attuned to the breeze. McNeice gets the character precisely right: gaudy, congenial, sardonic, a little cruel. I remember one particular announcement, a throwaway, really, but an example of the show actually inhabiting its setting rather than dully commenting on it. In the second season, when Herod is scheduled to visit Rome and its squabbling rulers, McNeice casually announces to the forum: “On order of the Triumvirate, during Prince Herod’s residency here, all mockery of Jews and their one god shall be kept to an appropriate minimum.” It’s the way he says “one god,” the slight pause that precedes it, the implied chuckle in the pronunciation . . . It’s very funny, and it’s very good.

HBO’s charming mid-aughts cosplay porno, Rome, habitually botched the broad canvas of history, but it did manage some excellent brush strokes, many of them dabbed around the series’ real star, Ian McNeice, who played the forum reader, a wonderfully amoral news anchor who stands in gorgeous fixity amid the whirl of war and upheaval, a pole whose flag is perfectly attuned to the breeze. McNeice gets the character precisely right: gaudy, congenial, sardonic, a little cruel. I remember one particular announcement, a throwaway, really, but an example of the show actually inhabiting its setting rather than dully commenting on it. In the second season, when Herod is scheduled to visit Rome and its squabbling rulers, McNeice casually announces to the forum: “On order of the Triumvirate, during Prince Herod’s residency here, all mockery of Jews and their one god shall be kept to an appropriate minimum.” It’s the way he says “one god,” the slight pause that precedes it, the implied chuckle in the pronunciation . . . It’s very funny, and it’s very good.

Pre-Christian Rome was religiously pluralistic, although it did have a state religion of sorts, and this was of a piece with the ancient world in general. It was accepted as a matter of course that different peoples had different gods, and over the centuries of migrations and conquests, people traded deities like we moderns trade vocabulary, with efforts to keep out popular foreign deities about as effective as the Académie française trying to keep out email. Even the Jews “and their one god” LOL had, in their past, occasionally adopted an idol, and when Adonai finally bothered to write down the bylaws, he admitted the dense population of the numinous world in his commandment: You shall have no other gods before me. The world is awash in divinities, but I am yours. The cheese stands alone.

Anyway, this all brings us by commodious vicus of recirculation back to America, our nova Roma, and the present to-do over gay rights and religious liberty. The general question is whether people of faith—another one of those hilarious taxonomic neologisms that are, I sometimes think, America’s sole remaining political export to the world—should be able, in a private capacity, to deny service to gays based on the religious and moral objections to homosexuality or gay marriage or what have you, or if this constitutes a form of discrimination as odious and intolerable to society as racial discrimination. Does refusing to bake a cake for a queer couple equal refusing to bake a cake for an interracial couple; does refusing to allow a gay parent to adopt amount to turning away black prospective parents at the agency door?

Obviously the general trend is in the direction of yes: yes, it is intolerable discrimination, and it isn’t permissible to raise the banner of free exercise in order to violate equal protection. Hmm, I suppose I find this logic a little weird. Now don’t get too worked up. I find religious objections to same-sex partnership and adoption incoherent; I find the Christian sexual ethics that supposedly stand in opposition to gay sex and gay marriage impossibly inconsistent and weird. The idea that there exists a such thing as “traditional marriage” and that some kind of post-War, pre-Beatles nuclear, two-generation family represents a sacred norm in human history is so laughably, ahistorically bogus as to represent, quite possibly, the dumbest idea in the magisterial history of dumb ideas. And like I said a few days ago, the old adage about reaping what you sow has few better examples than the specter of these people of faith, long perfectly pleased to link their religious institution to the packed list of state-sponsored and state-conferred benefits, now whining that this very same state should keep its muddy nose out of their churchy business. I hate the idea that I might be turned away at the door of a business because of my relationship with a man, but I am very suspicious of this constant appeal to the powers of the state, knowing, as I do, how the worm turns. Not very long ago, the same state that compels the baking of my wedding cake called my intimate life illegal. Or, the state that compels the lunch counter to serve black men also imprisons more than a million of them. What I am saying is, the problem of equality guaranteed by the police is the police.

The uncomfortable truth is that the idea of liberty sits uncomfortably with the free practice of religion. Another bogus idea is that liberty is some kind of natural state, a condition of freedom against which states and their governments set limits—reasonable and limited limits, if the state is properly constituted, yeah? But liberty in practical reality consists of a set of privileges and permissions; it is granted, not innate; it is a charter, not a condition of being, and as such, it is changeable, tradeable, and purchasable. It is not the same as freedom. The trouble with religious liberty as it’s come to be defined is that it asks the state to grant it the privilege to deny to others the permissions that the state has already granted. This is the strange demand: we wish to refuse what you permit.

I am a great believer in allowing many little cultures to flourish, and I think bad things happen when they start balling themselves up into the sorts of vast engines of wealth and authority that build thousands of prisons and stockpile nuclear weapons and invent aerial drones. But if we are to permit cultural peculiarity, and if we’re to permit broader exercises of moral expression, however attractive, however odious they may appear to us, then we must learn to live in a world of alien gods and weird wedding practices. A telling response to my last post was:

@j_arthur_bloom @jakebackpack Open borders, universal healthcare, gay marriage, & anti-religious liberty: All bad. @DouthatNYT

— Nathan Duffy (@TheIllegit) March 7, 2014

First we will deny you permission; then we won’t permit you to leave. This is why people find it so hard to believe that people of faith desire only to be left alone, to be allowed to run their adoption agencies, parochial schools, and sacramental marriage ceremonies without outside interference; live and let live; à chacun son goût; il faut cultiver notre jardin; um, etc. The plea to be allowed to be particular pairs poorly with an evangelical universalism; the desire to be granted liberty frequently shades into a wish to become its grantor; you shall have no other gods beside me, or before me, becomes rather more ominously, there shall be no other gods.

March 6, 2014

Ab hoedis me sequestra

I like to describe my politics as anarchist by belief and conservative by temperament. I’m the product of a close, multigenerational family, and most of us still live within twenty miles of where my paternal grandparents were born. Individually, we occupy a wide spectrum of idiosyncratic political beliefs, but, as is the case with many groups bound by old familial ties and economic interdependence, we tend, at least among ourselves, to be broad-minded. The habit of linking clannishness to close-mindedness has its roots in a certain truth, but the countervailing truth is that close kinship permits a tolerance for eccentricity that larger society often does not. At least, that’s my experience. As a moody adolescent very convinced of his own uniquely poetical character, I was very much prepared for my coming out to be my operatic moment contre le monde entier, and I suspect, in retrospect, that I was a little disappointed when no one seemed to care very much. To my extreme mortification, my father bought me condoms.

I was raised Jewish; I’m a bar mitzvah—that was from my mother’s side, per tradition, although my father, despite having been raised Catholic (my grandmother is Italian), is also half Jewish. My paternal grandfather, Fritz, was of German Jewish descent. In fact, we learned through amateur geneaology that his people were not German Jews at all, but Spanish Sephardim who migrated out of the Catholic south to escape various waves of persecution. Well, my grandmother is fond of saying that theirs was a controversial marriage at the time, an Italian Catholic and a German Jew. “But,” she says, “your grandfather married the only Italian woman who can’t cook, and I married the only Jew with no money.”

In the strictest sense of the word, I am an atheist, which is not to say I’m wholly irreligious. I still go to High Holy Day services and still think of myself as a Jew, and I believe in some kind of superphenomenal, if not supernatural, world, despite being a strict non-believer in any sort of deities or controlling intelligences—even dei absconditi strike me as silly, willful anthropomorphizations of the jumbled taxonomies of the limits of human understanding. So, I suppose, I am an unorthodox atheist. I did spend a lot of time in my twenties heckling actual believers for their historical and ontological lacunae, but I find myself, more and more, in a sort of aesthetic sympathy with religious faith. Perhaps it’s only because, as a writer, I must believe in a magical world or else despair of my art.

Over at The Atlantic, Conor Friedersdorf took issue with a Slate article that conflated all opposition to gay marriage with hatred, which moved Henry Farrell at Crooked Timber to complain that Friedersdorf was engaged in a game of canny semantics, eliding hatred and bigotry in such a way as to confuse the more fundamental truth that “Principled bigotry is still . . . bigotry,” that “Bigotry derived from religious principles is still bigotry.” Friedersdorf’s reasoning is a little sloppy, but Farrell goes out of his way to ignore or minimize Friedersdorf’s caveats. All of this, in any event, springs from a Ross Douthat article that I’ve been chewing on since it appeared last Sunday. “The Terms of Our Surrender” is the title, although the tone of it is rather Jewel-Voiced: the war situation has not necessarily developed to their advantage. Douthat knows that the juridical apparatus of the United States, a monster of momentum if ever there was one, is presently steaming in the direction of national gay marriage, and nothing is going to turn it around now. He is more gracious than his critics and interlocutors give him credit for:

Christians had plenty of opportunities — thousands of years’ worth — to treat gay people with real charity, and far too often chose intolerance. (And still do, in many instances and places.) So being marginalized, being sued, losing tax-exempt status — this will be uncomfortable, but we should keep perspective and remember our sins, and nobody should call it persecution.

This may be no more than a rhetorical gesture; the other contents of the essay strongly suggest that’s the case. Still, it’s not nothing. “We should . . . remember our sins” is not an insignificant statement from a believing Christian, even if it’s in the service of an otherwise specious argument.

But as to that other argument, I’m really struck by a single line:

Meanwhile, pressure would be brought to bear wherever the religious subculture brushed up against state power.

This is the crux of Douthat’s complaint, not that the popular, cultural advancement of tolerance, acceptance, and understanding has eroded what he and others like to call “traditional” marriage and sexual morality, but that, having at last moved into the winners’ column after a few decades of pitched legal competition, the gay victors will now avail themselves of the coercive power of the state to mandate compliance—that adoption agencies will be forced to accept gay parents or close; that religious schools will find it that much harder to teach that it is wrong for two men to have sex with each other, two women to marry.

I’m not unsympathetic. The coercive power of any government is an extraordinary thing, and the American government is the richest and most powerfully coercive in the world. It compels us all to behaviors we find morally dubious. We are all dragooned into paying for wars and assassinations, for a vast archipelago of incarceration, for corporate welfare and bank bailouts, for dubious public works, for the excesses of legislators, ad inf. There are tens of thousands of laws on the books, and there is a fair case to be made that each of us is, in the strictest terms, a daily felon because of them. It’s bad enough when the municipal government keeps giving you extortionate tickets for alternate-side on-street parking when they don’t even bother to actually sweep the streets in the ostensible fulfilment of the rationale for the regulation; how then must it feel to have the full force and majesty of the state and Federal governments attack the core moral tenets of your faith? However incorrect or retrograde they may appear to outsiders, you still believe.

Yes, but it would all be that much more convincing were it not for all the decades in which precisely that power was used to prop up those tenets, often cruelly, often arbitrarily, and often brutally. And it would be more convincing if this sort of supposed moral traditionalism were not also tied to the rather incoherent economics and cultural nativism of American political conservativism. Let me suggest, as just a couple of minor examples, that actual universal health care and reasonably open borders would ameliorate some of the more dire injustices faced by gay partners denied access to legally recognized marriage. Legal marriage is larded with all sorts of benefits and privileges, and indeed, it was often the very proponents of marriage as a distinct social good who held the larding needle. Married people are a special class of citizen, and that is the crux of the matter. A society used inheritance incentives and insurance benefits to promote a sacrament; now you want complain that the sacred has been subsumed by the economic, the holy spirit swatted aside by the invisible hand. Quantus tremor est futurus, quando judex est venturus, cuncta stricte discussurus!

The easy rejoinder is that conservatives believe in “smaller government” and a less coercive state, but that belief has never been a practical commitment, only a rhetorical strategy. The state grows under conservatives, and it grows under liberals. The difference is only a matter of emphasis, and frequently not even that. The truth is that these marriage traditionalists were perfectly content with state intervention in and support of their sacred institution when it hewed, more or less, to their membership requirements. Only when a bit of money and a bit of politicking rendered it a bit less restrictive, only then did those same agencies of the state become dangerous and a touch tyrannical. Those who play with fire, you know, and those who live by the sword.