Richard Conniff's Blog, page 3

April 12, 2023

How We Lived (and Died) Before Vaccines

By Richard Conniff/National Geographic

By Richard Conniff/National GeographicThis piece originally appeared in 2019. I’m republishing it now because it’s part of what motivated

my new book Ending Epidemics: A History of Escape from Contagion (MIT Press).

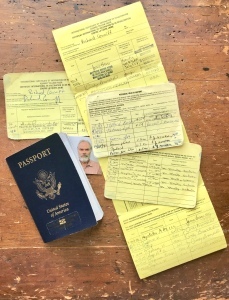

Like most American children of my generation, I lined up with my classmates in the mid-1950s to get the first vaccine for polio, then causing 15,000 cases of paralysis and 1,900 deaths a year in the United States, mostly in children. Likewise, we lined up for the vaccine against smallpox, then still causing millions of deaths worldwide each year. I’ve continued to update my immunizations ever since, including a few exotic ones for National Geographic assignments abroad, among them vaccines for anthrax, rabies, Japanese encephalitis, typhoid, and yellow fever.

Having grown up in the shadow of polio (my uncle was on crutches for life), and having made first-hand acquaintance with measles (I was part of the pre-vaccine peak year of 1958, along with 763,093 other young Americans), I’ve happily rolled up my sleeve for any vaccine recommended by my doctor and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, with extra input for foreign travel from the CDC Yellow Book. I am deeply grateful to vaccines for keeping me alive and well, and also for helping me return from field trips as healthy as when I set out.

Having grown up in the shadow of polio (my uncle was on crutches for life), and having made first-hand acquaintance with measles (I was part of the pre-vaccine peak year of 1958, along with 763,093 other young Americans), I’ve happily rolled up my sleeve for any vaccine recommended by my doctor and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, with extra input for foreign travel from the CDC Yellow Book. I am deeply grateful to vaccines for keeping me alive and well, and also for helping me return from field trips as healthy as when I set out.

One result of this willingness, however, is that I suffer, like most people, from a notorious Catch-22: Vaccines save us from diseases, then cause us to forget the diseases from which they save us. Once the threat appears to be gone from our lives, we become lax. Or worse, we make up other things to worry about. Thus, some well-meaning parents avoid vaccinating their children out of misplaced fear that the MMR vaccine (for measles, mumps, and rubella) causes autism. Never mind that independent scientific studies have repeatedly demonstrated that no such link exists, most recently in a study of 657,000 children in Denmark. This irrational fear is why the United States has experienced almost 1200 cases of measles so far this year, almost two decades after public health officials proudly declared it eliminated. About 124 of these measles victims, mostly children, have been hospitalized, 64 of them with complications including pneumonia and encephalitis, which can cause brain damage or death.

And yet autism can still seem like a bigger threat than measles, if only because it appears in countless television shows and movies such as “Rain Man” and “Gilbert Grape.” Meanwhile, you’re more likely to catch measles at a movie theater than see the disease featured onscreen.

And so, parents forget, or more likely never knew, that 33 of every 100,000 people who experienced actual measles ended up with mental retardation or central nervous system damage. (That’s in addition to those who died.)

They forget that an outbreak of rubella in the early 1960s resulted in 20,000 children being born with brain damage, including autism, and other congenital abnormalities.

They forget that, before it was eradicated by a vaccine in the 1970s, smallpox left many survivors blind, maimed, or brain damaged.

One remedy for this Catch-22 is to make a conscious effort to remind ourselves about the world before vaccines. Tdap, for instance, is a recurring but somewhat puzzling item on my immunization card. (Children get a slightly different formulation called DTaP.) The “T” is for tetanus and the “P” for pertussis, or whooping cough. But I was totally ignorant about the “D” for diphtheria.

Even doctors now tend to know the disease only from textbooks. But before the development of an effective vaccine in the early 1940s, diphtheria was among the great terrors of childhood. It killed more than 3,000 young Americans one year in the mid-1930s, when my parents were in high school. It is once again killing children today in Venezuela, Yemen, and other areas where social and political upheaval have disrupted the delivery of vaccine.

Among other symptoms, diphtheria produces a gray membrane of dead cells in the throat that can block a child’s windpipe, causing death by suffocation. Hence one of its nicknames: “the Strangling Angel.”

New England, where I live, suffered one of the deadliest epidemics in the 1730s and ‘40s—“the most horrible epidemic of a children’s disease in American history” according to one historian. It was made more horrible by the commonplace idea that it had been sent by God to punish sinful behavior. Or as a 1738 verse warned misbehaving boys and girls:

So soon as Death, hath stopt your Breath,

Your souls must then appear

Before the Judge of quick and dead,

The Sentence there to hear.

From thence away, without delay,

You must be Doom’d unto,

A dreadful Hell, where Devils dwell,

In Everlasting woe

Diphtheria was terrifying not only because it could kill with stunning speed, but also because it could hopscotch so easily from child to child by way of the coughing and sneezing it induced. Some families may also have unwittingly hastened the dying by having children line up to kiss a dying brother or sister goodbye. The results are still evident in our local burial grounds.

Grave of Ephraim, Hannah, and Jacob Mores (Photo: Heather Lennon)

In Lancaster, Massachusetts, for instance, mottled slate tombstones lean together, like family, over the graves of six children of Joseph and Rebeckah Mores. Ephraim, age seven, died first on June 15, 1740, followed by Hannah, three, on June 17, and Jacob, eleven, a day later. All three were buried in one grave. Then Cathorign, two, died on June 23, and Rebeckah, six, on June 26. The dying—five children gone in just 11 days—paused long enough to leave the poor parents some thin thread of hope. But two months later, on August 22, Lucy, 14, also died. A few years after that, diphtheria or some other epidemic disease came back to collect the three remaining Mores children.

Joseph and Rebeckah were by no means alone in their tragedy. Many other parents also lost all their children to diphtheria, in one case 12 or 13 in a single family. (In their stunned grief, the parents could not put an exact number on their loss.) On a single street less than a half-mile long in Newburyport, Massachusetts, 81 children died over three months in 1735. Haverhill, Massachusetts, lost half its children, with 23 families left childless.

Parents now rarely know such grief because our children are protected by vaccines, including Tdap/DTaP. It’s why we feel secure in having smaller families. It’s also a major reason life expectancy of newborns in the United States increased from 47.3 years at the start of the twentieth century to 76.8 at the end.

The level of this protection has continued to increase year by year in our own lifetimes, though the language of recommended immunizations tends to obscure these improvements. No parent has ever lost sleep, for instance, about something called “Hib,” short for “Haemophilus Influenzae Type B,” or about another pathogen called “rotavirus.”

But when he was starting out in the 1970s, “Hib dominated my residency,” says vaccinologist Paul Offit, M.D. It’s a major cause of childhood meningitis, pneumonia, and sepsis, a systemic blood infection. Children with this bacterial infection came into the emergency room so routinely that the hospital maintained a special darkened room with a fish tank to calm the child while an anesthesiologist rushed down and a surgical team prepared to operate. The danger, if the child became excited, was that the swollen, inflamed epiglottis would begin to spasm, blocking the windpipe.

“I had a lot of really painful conversations with parents when kids had meningitis or sepsis,” Offit recalls. “Often kids would have permanent hearing loss, intellectual deficits, motor deficits.”

Stanley Plotkin, M.D., also a vaccinologist, started out in the 1950s. Sixty years later he still recalls helplessly watching a child with a Hib disease “die under my hands.” A tracheostomy—a tube inserted through an incision in the windpipe below the blockage—would sometimes help. “But at the time I was an intern and didn’t know how to do a tracheostomy.”

Doctors (and parents) starting out today need not live with that particular memory. An effective vaccine introduced in the 1990s has reduced incidence of Hib disease in the United States by 99 percent, down from 20,000 to as low as 29 cases a year.

Rotavirus is an equally unfamiliar term for most parents. But it used to infect almost every child before the age of five and cause about 40 percent of severe infant diarrhea cases. In the absence of medical treatment, dehydration led to between 20 and 60 deaths a year in the United States and 500,000 deaths worldwide.

A vaccine for rotavirus became available in the 1990s, and in 2006 the CDC approved a safer version developed by Offit and Plotkin, together with the late H. Fred Clark, a microbiologist and social activist. Rotavirus-induced diarrhea has become rare as a result, preventing 40,000 to 50,000 hospitalizations of U.S. infants and toddlers every year. But in a California rotavirus outbreak in 2017, a child who had not been vaccinated still died of the disease, two months before its second birthday.

It is of course true that vaccinations entail risks, like everything else in the world. They range from the commonplace, like soreness at the site of injection, to the vanishingly rare, like a potentially life-threatening allergic reaction. Medical researchers are typically the first to identify and characterize these risks. A CDC study in 2016, for instance, looked at 25.2 million vaccinations over a three-year period and found 33 cases of severe vaccine-triggered allergic reaction—1.3 cases per million vaccine doses.

How should parents think about a risk like that? Being a good parent isn’t about protecting children from every medical risk. Instead, it’s about making a judgment, with advice from a doctor, about relative risk. Ask yourself: Which is worse for my child—the remote possibility of an allergic reaction, or the risk of Hib disease, rotavirus, pneumonia, or even chickenpox—which, despite its trivial reputation, killed 100 to 150 American children a year before the 1995 approval of an effective vaccine? Which is worse, a fictitious link between the MMR vaccine and autism—now dismissed as fraudulent even by the journal in which it was originally published—or exposing your child every day to the possibility of measles, with all its potentially deadly or debilitating consequences?

For my wife and I, the decision was always to get our children their recommended vaccinations. We still worried, as all parents do. But they stayed healthy, and we slept better, knowing we had put so many medical terrors of the past safely behind us.

END

Please check out Richard Conniff’s new book Ending Epidemics: A History of Escape from Contagion and spread the word to friends, to local bookshops, to libraries, and with reviews on Amazon or Goodreads. Thank you.

April 11, 2023

IT’S PUB DAY! AND I NEED YOUR HELP

Today’s pub day for my new book “Ending Epidemics: A History of Escape from Contagion” (MIT Press). Good stories need good readers, and I could definitely use your help to spread the word.

Below are some endorsements for the book–including the great defender of vaccine science Peter Hotez, MD, which turned up Sunday on Twitter.

Please feel free to repeat in whole or in pieces! And if you get the chance to read the book, please review it on Amazon, Goodreads, or by word of mouth. It all makes a huge difference to the book. Thank you.

“A taut interrogation of the centuries of labor that protected us from pathogens, a bitter lament for how quickly we abandoned our awareness of risk, and a stirring call for a new generation of disease fighters to take up the battle. Ending Epidemics drives home the post-COVID lesson of the peril of complacency.” —Maryn McKenna, author of Big Chicken, Superbug and Beating Back the Devil; Senior Fellow, Center for the Study of Human Health, Emory University

“Ending Epidemics is an important book, deeply and lovingly researched, written with precision and elegance, a sweeping story of centuries of human battle with infectious disease. Conniff is a brilliant historian with a jeweler’s eye for detail. I think the book is a masterpiece.” ––Richard Preston, author of The Hot Zone and The Demon in the Freezer

“A timely and highly readable account of humanity’s struggles and progress in the fight against infectious disease. Set across three centuries, from the birth of immunology to the antibiotic revolution, Conniff draws on the personal stories behind these great medical and scientific leaps. A fascinating read with powerful lessons for tackling today’s—and indeed future—epidemics.” ––Peter Piot, Former Director and Handa Professor of Global Health, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine; author of No Time to Lose and AIDS: Between Science and Politics

“A dramatic, page-turning account of the grim, never-ending war waged by infections on humankind. And how we fought back, sometimes successfully, sometimes not.” —Paul A. Offit, Professor of Pediatrics, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia; author of You Bet Your Life—From Blood Transfusions to Mass Vaccinations, the Long and Risky History of Medical Innovation

“I’ve been reading this new book by @RichardConniff sent to me by @bobprior @mitpress. I like it very much. Similar topics to those in Microbe Hunters but more balanced nuanced and attention to accuracy. It’s well written and hard to put down. @DrPaulOffit endorsed it and I agree!” — Prof. Peter Hotez, Vaccine Scientist-Author-Combat Antiscience, @bcmhouston, Professor Pediatrics Molecular Virology, @bcm_tropmed, Dean, @TexasChildrens Chair in Tropical Pediatrics

Last word: At the moment, the best price seems to be at this site, which also benefits local booksellers.

January 26, 2023

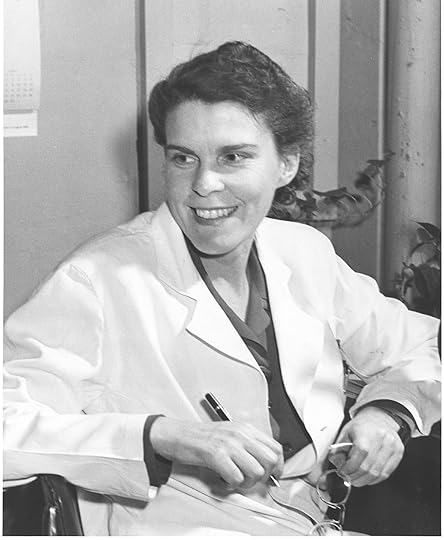

Salk and His Polio Vaccine? This Woman Figured It Out First.

Her name was Isabel Morgan (1911–1996). She was a virologist at Johns Hopkins University. And in 1947, she demonstrated the first effective polio immunization in rhesus monkeys. Morgan had devised a formalin-inactivated vaccine, at a time when most polio researchers believed such a vaccine could not possibly work.

“She converted us and that was quite a feat,” one of her many male colleagues conceded.

That vaccine was the forerunner of the one Jonas Salk introduced eight years later in humans.

So how come you’ve never heard of Isabel Morgan?

Read her story and those of other public health pioneers in Ending Epidemics–A History of Escape from Contagion (due out April 12, MIT Press). TODAY ONLY–January 26 2023–the code PREORDER25 will get you a 25% discount from Barnes & Nobel.

Advance praise for Ending Epidemics: “A timely and highly readable account of humanity’s struggles and progress in the fight against infectious disease. Set across three centuries, from the birth of immunology to the antibiotic revolution, Conniff draws on the personal stories behind these great medical and scientific leaps. A fascinating read with powerful lessons for tackling today’s—and indeed future—epidemics.” — Peter Piot, Former Director and Handa Professor of Global Health, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine

and author of No Time to Lose and AIDS: Between Science and Politics

“A dramatic, page-turning account of the grim, never-ending war waged by infections on humankind. And how we fought back, sometimes successfully, sometimes not.” —Paul A. Offit, Professor of Pediatrics, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia; author of You Bet Your Life—From Blood Transfusions to Mass Vaccinations, the Long and Risky History of Medical Innovation.

January 8, 2023

On the Origin of a Theory

by Richard Conniff

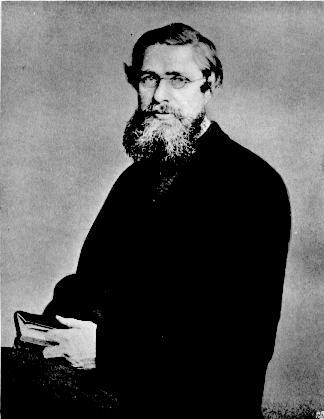

This is an excerpt from my book The Species Seekers, and I am publishing it here today to honor the 200th birthday of Alfred Russel Wallace, co-founder of evolutionary theory.

Alfred Russel Wallace

Alfred Russel WallaceLeafing through the mail at his home outside London one June day 150 years ago, Charles Darwin came across an envelope sent from an island in what is now part of Indonesia. The writer was a young acquaintance, Alfred Russel Wallace, who eked out a living as a biological collector, sending butterflies, bird skins and other specimens back to England. This time, Wallace had sent along a 20-page manuscript, requesting that Darwin show it to other members of the British scientific community.

As he read, Darwin saw with dawning horror that the author had arrived at the same evolutionary theory he had been working on, without publishing a word, for 20 years. “All my originality, whatever it may amount to, will be smashed,” he lamented in a note to his friend the geologist Charles Lyell. Darwin ventured that he would be “extremely glad now” to publish a brief account of his own lengthy manuscript, but that “I would far rather burn my whole book than that [Wallace] or any man should think that I had behaved in a paltry spirit.”

The threat to his life’s work could hardly have come at a worse moment. Darwin’s daughter Etty, 14, was frighteningly ill with diphtheria. His 18-month-old son, Charles, would soon lie dead of scarlet fever. Lyell and another Darwin friend, the botanist Joseph Hooker, cobbled together a compromise, rushing both Darwin’s and Wallace’s works before a meeting of the Linnean Society a few days later, on July 1, 1858. The reading took place in a narrow, stuffy ballroom at Burlington House, just off Piccadilly Circus, and neither author was present. (Darwin was at his son’s funeral; Wallace was in New Guinea.) Nor was there any discussion. The society’s president went home muttering about the lack of any “striking discoveries” that year. And so began the greatest revolution in the history of science.

We call it Darwinism, for short. But in truth, it didn’t start with Darwin, or with Wallace either, for that matter. Great ideas seldom arise in the romantic way we like to imagine—the bolt from the blue, the lone genius running through the streets crying, “Eureka!” Like evolution itself, science more often advances by small steps, with different lines converging on the same solution.

“The only novelty in my work is the attempt to explain how species become modified,” Darwin later wrote. He did not mean to belittle his achievement. The how, backed up by an abundance of evidence, was crucial: nature throws up endless biological variations, and they either flourish or fade away in the face of disease, hunger, predation and other factors. Darwin’s term for it was “natural selection”; Wallace called it the “struggle for existence.” But we often act today as if Darwin invented the idea of evolution itself, including the theory that human beings developed from an ape ancestor. And Wallace we forget altogether.

In fact, scientists had been talking about our primate origins at least since 1699, after the London physician Edward Tyson dissected a chimpanzee and documented a disturbing likeness to human anatomy. And the idea of evolution had been around for generations.

In the 1770s, Darwin’s grandfather Erasmus Darwin, a physician and philosopher, publicly declared that different species had evolved from a common ancestor. He even had the motto “E conchis omnia” (“Everything from shells”) painted on his carriage, prompting a local clergyman to lambaste him in verse:

Great wizard he! by magic spells

Can all things raise from cockle shells.

In the 1794 book of his two-volume Zoonomia, the elder Darwin ventured that over the course of “perhaps millions of ages…all warm-blooded animals have arisen from one living filament,” acquiring new traits and passing down improvements from generation to generation.

His contemporary Samuel Taylor Coleridge mocked this sort of evolutionary theory as “darwinizing.” But it was by no means a family monopoly. Evolutionary questions confronted almost all naturalists of that era as expeditions to distant lands discovered a bewildering variety of plants and animals. Fossils were also turning up in the backyard, threatening the biblical account of Creation with evidence that some species had gone extinct and been supplanted by new species. The only way to make sense of these discoveries was to put similar species side by side and sort out the subtle differences. These comparisons led “transmutationists” to wonder if species might gradually evolve over time, instead of having a fixed, God-given form.

In 1801, the French naturalist Jean-Baptiste Lamarck proposed that species could change in response to environmental conditions. Giraffes, for instance, had developed their fantastic necks to browse on the upper branches of trees. Lamarck mistakenly thought such traits could be acquired by one generation and passed on to the next. He is ridiculed, to this day, for suggesting that giraffes got their longer necks basically by wanting them (though the word he used, some scholars contend, is more accurately translated as “needing”). But his was the first real theory of evolution. If he had merely suggested that competition for treetop foliage could gradually put short-necked giraffes at a disadvantage, we might now be talking about Lamarckian, rather than Darwinian, evolution.

By the 1840s, evolutionary ideas had broken out of the scientific community and into heated public debate. The sensation of 1845 was the anonymous tract Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation, and it set both Darwin and Wallace on career paths that would converge in that fateful 1858 mail delivery. Vestiges deftly wove evolutionary ideas into a sweeping history of the cosmos, beginning in some primordial “fire-mist.” The author, later revealed to be the Edinburgh journalist and publisher Robert Chambers, argued that humans had arisen from monkeys and apes, but he also appealed to ordinary readers with the uplifting message that evolution was about progress and improvement.

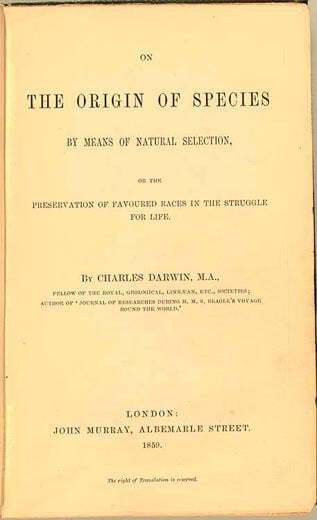

Title page for Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species Library of Congress

Title page for Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species Library of CongressVestiges quickly became a popular hit, a rose-tinted 2001: A Space Odyssey of its day. Prince Albert read it aloud to Queen Victoria at Buckingham Palace, and it was the talk of every gentlemen’s club and social soiree, according to James A. Secord, author of Victorian Sensation. Jocular types greeted each other on the street with phrases like, “Well, son of a cabbage, whither art thou progressing?” Others took evolution more seriously. On a museum visit, Florence Nightingale noticed that small flightless birds of the modern genus Apteryx had vestigial wings like those of the giant moa, an extinct bird that had recently been discovered. One species ran into another, she remarked, much “as Vestiges would have it.”

Clergymen railed from the pulpit against such thinking. But scientists, too, hated Vestiges for its loose speculation and careless use of facts. One indignant geologist set out to stamp “with an iron heel upon the head of the filthy abortion, and put an end to its crawlings.” In Cambridge, at a meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, an astronomer criticized the book’s failure to explain how evolution might have occurred; Vestiges, in his view, was about as miraculous as the biblical account of Creation. (During this attack, the author, still anonymous, sat in the front row, probably trying not to squirm.) Even Darwin disliked what he called “that strange unphilosophical, but capitally-written book.” He confided to a friend that the author’s “geology strikes me as bad, & his zoology far worse.”

Darwin had begun to develop his own theory of evolution seven years earlier, in 1838, while reading the demographer T. R. Malthus on factors limiting human population growth. It dawned on him that, among animals, hunger, predation and other “checks” on population could provide “a force like a hundred thousand wedges,” thrusting out weaker individuals and creating gaps where better-adapted individuals could thrive. By 1844, he had expanded this idea into a manuscript of more than 200 pages.

But Vestiges heightened Darwin’s characteristic caution. He hesitated to publish partly because radicals were taking up evolutionary theory as a way to undermine the idea of a divinely ordained social hierarchy. Darwin himself sat comfortably in the upper ranks of that hierarchy; he had inherited wealth, and his closest colleagues were other gentlemen naturalists, including the clergy. Admitting transmutationist beliefs in these circles, Darwin had written to his friend Hooker, would be like “confessing a murder.” But beyond that, he also hesitated because the abuse being heaped onto Vestiges drove home the need for detailed evidence. Darwin, at age 37, backed away from theorizing and settled down to describing the minute differences within one invertebrate group: the barnacles. He would spend the next eight years at it, at some peril to his sanity.

Wallace was more receptive to Vestiges. He was just 22 when the controversy raged. He also came from a downwardly mobile family and had a penchant for progressive political causes. But Vestiges led him to the same conclusion about what needed to be done next. “I do not consider it as a hasty generalization,” Wallace wrote to a friend, “but rather as an ingenious speculation” in need of more facts and further research. Later he added, “I begin to feel rather dissatisfied with a mere local collection…. I should like to take some one family to study thoroughly—principally with a view to the theory of the origin of species.” In April 1848, having saved £100 from his wages as a railroad surveyor, he and a fellow collector sailed for the Amazon. From then on, Wallace and Darwin were asking the same fundamental questions.

Ideas that seem obvious in retrospect are anything but in real life. As Wallace collected on both sides of the Amazon, he began to think about the distribution of species and whether geographic barriers, such as a river, could be a key to their formation. Traveling on HMS Beagle as a young naturalist, Darwin had also wondered about species distribution in the Galápagos Islands. But pinning down the details was tedious work. As he sorted through the barnacles of the world in 1850, Darwin muttered darkly about “this confounded variation.” Two years later, still tangled up in taxonomic minutiae, he exclaimed, “I hate a Barnacle as no man ever did before.”

Wallace was returning from the Amazon in 1852, after four years of hard collecting, when his ship caught fire and sank, taking down drawings, notes, journals and what he told a friend were “hundreds of new and beautiful species.” But Wallace was as optimistic as Darwin was cautious, and soon headed off on another collecting expedition, to the islands of Southeast Asia. In 1856, he published his first paper on evolution, focusing on the island distribution of closely related species—but leaving out the critical issue of how one species might have evolved from its neighbors. Alarmed, Darwin’s friends urged him to get on with his book.

By now, the two men were corresponding. Wallace sent specimens; Darwin replied with encouragement. He also gently warned Wallace off: “This summer will make the 20th year (!) since I opened my first-note-book” on the species question, he wrote, adding that it might take two more years to go to press. Events threatened to bypass them both. In England, a furious debate erupted about whether there were significant structural differences between the brains of humans and gorillas, a species discovered by science only ten years earlier. Other researchers had lately found the fossil remains of brutal-looking humans, the Neanderthals, in Europe itself.

Eight thousand miles away, on an island called Gilolo, Wallace spent much of February 1858 wrapped in blankets against the alternating hot and cold fits of malaria. He passed the time mulling over the species question, and one day, the same book that had inspired Darwin came to mind—Malthus’ Essay on the Principle of Population. “It occurred to me to ask the question, Why do some die and some live?” he later recalled. Thinking about how the healthiest individuals survive disease, and the strongest or swiftest escape from predators, “it suddenly flashed upon me…in every generation the inferior would inevitably be killed off and the superior would remain—that is, the fittest would survive.” Over the next three days, literally in a fever, he wrote out the idea and posted it to Darwin.

Less than two years later, on November 22, 1859, Darwin published his great work On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, and the unthinkable—that man was descended from beasts—became more than thinkable. Darwin didn’t just supply the how of evolution; his painstaking work on barnacles and other species made the idea plausible. Characteristically, Darwin gave credit to Wallace, and also to Malthus, Lamarck and even the anonymous “Mr. Vestiges.” Reading the book, which Darwin sent to him in New Guinea, Wallace was plainly thrilled: “Mr. Darwin has given the world a new science, and his name should, in my opinion, stand above that of every philosopher of ancient or modern times.”

Wallace seems to have felt no twinge of envy or possessiveness about the idea that would bring Darwin such renown. Alfred Russel Wallace had made the postman knock, and that was apparently enough.

Richard Conniff is a longtime contributor to Smithsonian and the author of The Species Seekers.

September 7, 2022

ENDING EPIDEMICS: Announcing My New Book

If you’re one of the good people who have enjoyed my previous books, you could be a great help with my new one, Ending Epidemics: A History of Escape from Contagion. Barnes and Noble is offering a 25% discount with the code PREORDER25, today and tomorrow only.

Paul Offit, M.D., author of You Bet Your Life and other books on public health, calls it “A dramatic, page-turning account of the grim, never-ending war waged by infections on humankind.”

Pre-ordering sends a big message of reader support to bookstores & marketing folks. Please also spread the word with your friends, social media contacts, and your local bookstore. It can make or break this book.

You can read more about the book from the publisher MIT Press: “Ending Epidemics tells the story behind “the mortality revolution,” the dramatic transformation not just in our longevity, but in the character of childhood, family life, and human society. Richard Conniff recounts the moments of inspiration and innovation, decades of dogged persistence, and, of course, periods of terrible suffering that stir individuals, institutions, and governments to act in the name of public health.”

You can also read a sample chapter here, about two forgotten women whose work saves tens of thousands of small children every year from death by whooping cough.

May 11, 2022

The Unsung Heroes Who Ended a Deadly Plague

Grand Rapids, Michigan, shortly before the Depression. (Photo: Unknown)

Grand Rapids, Michigan, shortly before the Depression. (Photo: Unknown)by Richard Conniff/Smithsonian Magazine

Late November 1932, the weather cold and windy, two women set out at the end of their normal working day into the streets of Grand Rapids, Michigan. The Great Depression was entering its fourth year. Banks had shut down, and the city’s dominant furniture industry had collapsed. Pearl Kendrick and Grace Eldering both biologists for a state laboratory, were working on their own time to visit sick children and determine if they were infected with a potentially deadly disease. Many of the families lived in “pitiful” conditions,” they later recalled. “We listened to sad stories told by desperate fathers who could find no work. We collected specimens by the light of kerosene lamps, from whooping, vomiting, strangling children. We saw what the disease could do.”

It could seem at first like nothing all, a runny nose and a mild cough. A missed diagnosis is common even now: Just a cold, nothing to worry about. After a week or two, though, the coughing can begin to come in violent spasms, too fast for breathing, until the sharp, strangled bark breaks through of the child desperately gasping to get air down her throat. That whooping sound makes the diagnosis unmistakable.

Whooping cough, also known as pertussis, means nothing to most parents in the developed world today. But the helpless feeling of watching a baby in the agonizing grip of a prolonged coughing spasm is unforgettable. “It’s awful, it’s awful. You wonder how they can survive the crisis,” says a modern researcher who has seen it. “I mean, they’re suffocating. They’re choking. They become completely blue. They cannot overcome the cough, and you have the impression that the child is dying in your hands.” It can go on like that for weeks, or months.

Until the mid-twentieth century, there was also nothing anyone could do to prevent the disease. It was so contagious that one child with whooping cough was likely to infect half his classmates, and all his siblings at home. In the 1930s, it killed 4000 Americans on average every year, most of them still infants. Survivors could suffer permanent physical and cognitive damage.

All that changed because of Kendrick and Eldering, now largely forgotten. They’d been hired to conduct routine daily testing of medical and environmental samples at a state laboratory. But whooping cough became their obsession. They worked on it late into the night, without funding at first, in what a reporter later described it as a “dumpy broken down stucco” building. They benefited from the work of their own hand-picked research team, which was remarkably diverse for that era in race, gender, and even sexual orientation. They also enlisted the trust and enthusiasm of their community.

Medical men with better credentials were deeply skeptical. But where other researchers had failed repeatedly over the previous 30 years, Kendrick, Eldering, and their team succeeded in developing the first reliably effective whooping cough vaccine. Childhood deaths from whooping cough soon plummeted in the United States, and then the world. (To continue reading, click here)

January 12, 2022

SOLAR BELONGS ON PARKING LOTS & ROOFTOPS, NOT FIELDS & FORESTS

A solar-covered parking lot at an engine plant in Chuzhou, China. (Photo: Imaginechina via AP Images)

A solar-covered parking lot at an engine plant in Chuzhou, China. (Photo: Imaginechina via AP Images)by Richard Conniff/Yale Environment 360

Fly into Orlando, Florida, and you may notice a 22-acre solar power array in the shape of Mickey Mouse’s head in a field just west of Disney World. Nearby, Disney also has a 270-acre solar farm of conventional design on former orchard and forest land. Park your car in any of Disney’s 32,000 parking spaces, on the other hand, and you won’t see a canopy overhead generating solar power (or providing shade) — not even if you snag one of the preferred spaces for which visitors pay up to $50 a day.

This is how it typically goes with solar arrays: We build them on open space rather than in developed areas. That is, they overwhelmingly occupy croplands, arid lands, and grasslands, not rooftops or parking lots, according to a global inventory published last month in Nature. In the United States, for instance, roughly 51 percent of utility-scale solar facilities are in deserts; 33 percent are on croplands; and 10 percent are in grasslands and forests. Just 2.5 percent of U.S. solar power comes from urban areas.

The argument for doing it this way can seem compelling: It is cheaper to build on undeveloped land than on rooftops or in parking lots. And building alternative power sources fast and cheap is critical in the race to replace fossil fuels and avert catastrophic climate change. It’s also easier to manage a few big solar farms in an open landscape than a thousand small ones scattered across urban areas.

But that doesn’t necessarily make it smarter. Undeveloped land is a rapidly dwindling resource, and what’s left is under pressure to deliver a host of other services we require from the natural world — growing food, sheltering wildlife, storing and purifying water, preventing erosion, and sequestering carbon, among others. And that pressure is rapidly intensifying. By 2050, in one plausible scenario from the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL), supplying solar power for all our electrical needs could require ground-based solar on 0.5 percent of the total land area of the United States. To put that number in perspective, NREL senior research Robert Margolis says it’s “less land than we already dedicate to growing corn ethanol for biofuels.” (Continue reading)

December 27, 2021

E.O. WILSON on Cooperation & the Tribal Mind

Photo: Gerald Forster

Photo: Gerald Forsterby Richard Conniff

Discover Magazine, June 2006

Edward O. Wilson has spent a lifetime squinting at ants and has come away with some of the biggest ideas in evolutionary biology since Darwin. “Sociobiology” and “biodiversity” are among the terms he popularized, as is “evolutionary biology” itself.

He has been in the thick of at least two nasty scientific brawls. In the 1950s, his field of systematics, the traditional science of identifying and classifying species based on their anatomies, was being shoved aside by molecular biology, which focused on genetics. His Harvard University colleague James Watson, codiscoverer of the structure of DNA, declined to acknowledge Wilson when they passed in the hall. Then in the 1970s, when Wilson published Sociobiology: The New Synthesis, other Harvard colleagues attacked the idea of analyzing human behavior from an evolutionary perspective as sexist, racist, or worse. He bore all the hostility in the polite, courtly style of his Southern upbringing, and largely prevailed. Sociobiology, though still controversial, has become mainstream as evolutionary psychology. The molecular biology wars may also be ending in a rapprochement, he says, as the “test tube jockeys” belatedly recognize that they need the “stamp collector” systematists after all.

Wilson, who turns 77 this month, has published three books during the past year that fit his own wry definition of a magnum opus: “a book which when dropped from a three-story building is big enough to kill a man.” Nature Revealed (Johns Hopkins) is a selection of his writings since 1949. From So Simple a Beginning (W. W. Norton) is an anthology of writings by Darwin, and Pheidole in the New World (Harvard) is a reorganization of an entire ant genus, including 341 new species Wilson discovered and more than 600 of his own drawings.

RC: You once wrote that you saw yourself parading provocative ideas “like a subaltern riding the regimental colors along the enemy line.”

Wilson: That’s right, “along the enemy line.” That’s an adolescent and very Southern way of putting it, but I wanted to say that I’m a risk taker at heart.

RC: And a provocateur?

Wilson: Yes, but not a controversialist. There’s a distinction. Once I feel I’m right, I have enjoyed provoking.

RC: Your adversaries from the 1970s would be appalled by how much your ideas about sociobiology have taken hold.

Wilson: The opposition has mostly fallen silent. Anyway, it was promoted by what turned out to be a very small number of biologists with a 1960s political agenda. Most of the opposition came from the social sciences, where it was visceral and almost universal.

RC: The social scientists were threatened by the invasion of their territory?

Wilson: That’s right.

RC: The same way that you were threatened by the molecular biologists invading the biological field in the 1950s?

Wilson: They didn’t invade it so much as they dismissed it. What’s been gratifying is to live long enough to see molecular biology and evolutionary biology growing toward each other and uniting in research efforts. It’s personally satisfying and symbolic that Jim Watson and I now get on so well. We even appeared onstage a couple of times together during the 50th anniversary year of the discovery of DNA.

RC: You once described Watson as “the most unpleasant human being” you’d ever met. (Continued)

April 8, 2021

U.S. Cities Are Losing Tree Cover Just When They Need It Most

by Richard Conniff/Scientific American

by Richard Conniff/Scientific AmericanScientific evidence that trees and green spaces are crucial to the well-being of people in urban areas has multiplied in recent decades. Conveniently, these findings have emerged just as Americans, already among the most urbanized people in the world, are increasingly choosing to live in cities. The problem—partly as a result of that choice—is that urban tree cover is now steadily declining across the U.S.

A study in the May 2018 issue of Urban Forestry & Urban Greening reports metropolitan areas are experiencing a net loss of about 36 million trees nationwide every year. That amounts to about 175,000 acres of tree cover, most of it in central city and suburban areas but also on the exurban fringes. This reduction, says lead author David Nowak of the U.S. Forest Service (USFS), translates into an annual loss of about $96 million in benefits—based, he says, on…

View original post 1,168 more words

April 7, 2021

It’s Time for a Carbon Tax on Beef

Let me admit up front that I would rather be eating a cheeseburger right now. Or maybe trying out a promising new recipe for Korean braised short ribs. But our collective love affair with beef, dating back more than 10,000 years, has gone wrong, in so many ways. And in my head, if not in my appetites, I know it’s time to break it off.

So it caught my eye recently when a team of French scientists published a paper on the practicality of putting a carbon tax on beef as a tool for meeting European Union climate change targets. The idea will no doubt sound absurd to Americans reared on Big Macs and cowboy mythology. While most of us recognize, according to a 2017 Gallup poll, that we are already experiencing the effects of climate change, we just…

View original post 900 more words