Cheryl R. Cowtan's Blog, page 3

October 13, 2018

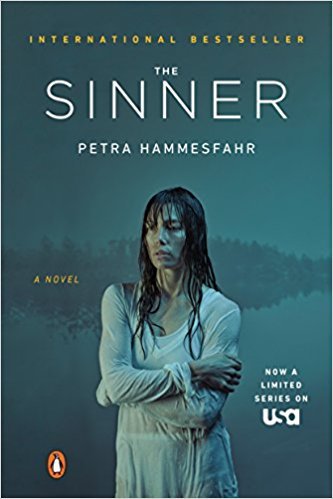

The S I N N E R

I recently watched the crime drama, mystery television series, “The Sinner”, a story in which a detective with his own past tries to uncover why a seemingly “normal” woman would commit a brutal and senseless crime. This series teaches two things every author should know:

The more a character has suffered, the more the reader will be rooting for them to win.

A plot device can include taking the abnormal and unraveling it to the normal (as opposed to the other way around).

The second point I had never really thought of for my own work. My skills shine in the other way: I take the normal and twist it into the abnormal. A reverse was an astounding idea for me, especially as I continue writing my third novel in The Fergus She series. My character’s story is so complex at this point, I don’t think I could ever weave the plot lines into normalcy, and I surely don’t want to. But for future novels, I might just construct that type of plot.

The basis for the Emmy-nominated “instantly gripping” (Washington Post) limited series starring Jessica Biel, The Sinner, is an internationally bestselling psychological thriller surrounding an unexplained murder.

July 16, 2018

Russell Crowe for the sexy, but uncaring Groundsman in Master of Madhouse

As an author, I sometimes wonder who would best play the roles in my novels.

I recently watched an enjoyable comedy called The Nice Guys. In the movie was this actor I like, but I've never taken the time to find out his name. I was thinking he'd make a fabulous groundsman in Master of Madhouse, because he can pull off sexy, older man who can handle a gun and get things done, but who appears to have no empathy for others, yet you just know, underneath all that Molson muscle, a warm heart beats.

So, I look up the unknown actor and surprise! It's Russell Crowe.

Before you judge me as a complete celebrity granite, I want to assure you I know who Russell Crowe is! Apparently, I just can't recognize the man when he's acting. I hesitate to assume my inability to recognize Crowe is due to the fact that he's a great character actor, because he generally portrays a kind of quiet, brooding man who can get things done. So, why? Why can't I recognize him.

To find out , I watched a few of his movies in a row, and here's how he's been hiding out on me:

~~Cinderella Man (New Jersey accent, he actually smiles)

~~Robin Hood (English accent, I don't think he smiles)

~~The Nice Guys (American accent, a half-smile, maybe)

So, there you have it. He changes his accent, and so I never think he's the same guy. LOL I fool easy.

Seriously, the only conclusion I came to in my research was that if Russell Crowe is in the film, it's probably a good movie.

Disclaimers:

*Yes, I'm aware New Joisey's in America

*Yes, I'm aware Russell Crowe doesn't need to smile

*Yes, I now know his name is spelt with two LLs.

*Yes, I'm aware Crowe turned down the roles of Logan/Wolverine and Aragorn in Lord Of the Rings.

What? What a loss. But I wouldn't have known it was him anyways because in Wolverine he'd be talking like a Canadian, and in LoT, he'd be speaking Elvish.

*Yes, I'm aware I'm a Canadian

When you read Master of Madhouse and make sure you give the groundsman Crowe's voice.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

I knew her type. She was from a kick-hill house. Whoever was on the bottom got kicked by everybody, and whoever was on the top could kick the rest. It’s why she took my beating. I was stronger, so I had the right to hit her. The logic was terrifyingly simple.

“I asked you a question,” I said with more threat.

As I expected, she caved. “He’s the groundsman.”

She started up the next step, and I grabbed the back of her shift to buy myself more breathing time. “What does the groundsman do?” I asked between puffs.

“He keeps the poachers away and manages the master’s game,” she snarled and slapped my hand away.

“Game… like some sort of chess game?”

She laughed in scorn and I took it. I could give her this.

“Game meat, what you hunt and eat,” she said slowly, as if she were talking to a simpleton.

And really, she was. I came from the land of grocery stores where “game” was killed, cleaned and packaged long before I had to see it.

Game meat. The words sunk in.

“Am I game?” I whispered looking back down the wooden stairs behind me.

She snickered, letting me know she and I were equals in the kick-hill. I wasn’t on top. Gräfen was, and we were all below him.

“Wouldn’t want to be you,” she said in a warning voice, and continued up the never-ending staircase.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Read 4 FREE chapters from Master of Madhouse

August 30, 2017

The Bloodstone Reckoning, Michael Wigington

Looking for a quality book reviewer? I’m loving reading through RedHeadedBookLoverBlog’s reviews.

Source: The Bloodstone Reckoning, Michael Wigington

August 23, 2017

The Self-Reflecting Art Gallery: Lowry’s Consul and Goethe’s Faust

Have you ever seen yourself, peeking out between the strokes of colour on a canvas? Artists often portray the human condition as seen through their individual perceptions, so it is not unlikely that you, or I, or Faust may be trapped on a wall somewhere. Not literally of course, but some aspect of personality, desire, or behaviour has been captured in art and could be, when viewed, the key to self-understanding. Writer Malcolm Lowry was aware of this self-reflecting art gallery when he wrote Under the Volcano, as was Goethe when he created Faust. Lowry’s Consul has distorted his self-perception with alcohol and Goethe‘s Faust has distorted his self-perception with negativity, yet both are able to clarify their sense-of-self through viewing art and begin on a new path.

Like adolescents, who are caught in a “transitional period” of self discovery, Faust and the Consul are struggling under “the major task [of finding] a sense of self identity” (Richardson). Faust is unsatisfied with himself and his accomplishments, and the Consul is slowly losing his self to alcoholism. An aware self has “a sense of being in control of its actions, of continuity in time” claims Ramachandran, a neuroscientist at the University of California. The Consul’s control over his free will to act and his sense of time is compromised by his addiction to alcohol. The Consul is aware that his abuse of alcohol was a factor in his wife’s infidelity and her decision to divorce him, yet he cannot stop drinking once she returns to reconcile. When his ex-wife returns after a year of absence, his “first thoughts” are for a drink (Lowry 74). The Consul has enough self-awareness left to realize that this is inappropriate, and he tries to exercise his will to control his need for alcohol. “I have resisted temptation for two and a half minutes at least . . .” (74). His resistance will only last for a few more minutes as his will breaks down in steps; he uncorks and sniffs the whiskey, reaches and draws back from the other bottles and finally sneaks off to find a drink outside of the house while his wife bathes. (79-81). Though the Consul knows he should not have a drink, his addiction overcomes his free will and he is unable to stop himself. Who the Consul is, what he does and what he thinks is controlled by his addiction–his self-autonomy is compromised and his strength of will is weakened with tequila, mescal and beer.

The Consul also has a poor “sense of continuity of time”. While the Consul is debating with himself on whether he should have a before-breakfast drink, his wife is tells him “three times” to have a “decent drink” (75). The Consul does not hear her because his alcohol-diseased mind cannot keep track of time or reality. It is busy listening to his split conscience, which the Consul refers to as his first and second “familiars” (75). While the Consul is trying to sort out his thoughts about his wife, the familiars are harassing him about drinking. The confused, split state leaves the Consul barely able to carry on a conversation, much less make life decisions and act on them. The Consul moves in and out of reality and his thoughts and spoken words blur until he is not sure what he has said aloud.

Inner dialogues are not the Consul’s only distractions from time. He is unable to perform simple actions in the order required. “The Consul struck a match . . . for the cigarette he had somehow failed to place between his lips. . .” (80). This inability to manage actions and time is reflected in the run-down condition of the gardens and pool. “. . . the garden sloped off beyond into an indescribable confusion of briars from which the Consul averted his eyes” (72). The Consul’s main preoccupation is to find the next drink, and this single-minded purpose has left him living in a state of chaos and decay. The house and surrounding garden seem to reflect the condition of the Consul, who is rapidly deteriorating. “… the drooping plants, dusty and gone to seed . . . The stained hammock, … the bad melodrama of the broken chair … (73). and is caused by sleep depravation on top of alcoholism. The Consul warns his wife of his condition by stating that he is “in a frightfully jolly mess . . .” (76). He can recognize his situation so he is self-aware, but he has little self-control. This once competent Consulate of England, has become a struggling, diseased person, unable to care for his own health, or organize his thoughts. The deterioration of his abilities and personality leave the Consul with a confused sense-of-self.

The Consul’s confusion also stems from disturbed patterns of rest. Each morning, the Consul does not know what may have transpired the night before, because he is drunk on a daily basis. He speaks of the approaching memories of the “ursa horribilis of the night” and wonders where he has slept and what he has done (75). Walking to a cantina while his wife bathes, he completely passes out on the road (82). Later, within the same hour, he falls asleep “with a crash” and it is not even 10:00 a.m. yet (97). The Consul’s sense of time is not continuous nor reliable, as he moves in and out of reality and consciousness. His life’s clock tics and tocs between sobriety and drunkenness and each hour he loses, he loses a part of his self to his addiction. This deterioration confuses his sense of self in two ways; first by making him unable to concentrate long enough to think or understand, and second, by continuing the assault on his body. Therefore, the Consult cannot grasp who he is, has little self-worth or dignity left and perceives no life-goal other than getting the next drink.

Whereas the Consul is losing his sense of identity to alcoholism, Faust purposefully creates a negative sense of self with his destructive thinking. Ramachandran’s other aspects of self include “a sense of . . . worth, dignity and morality (or immorality)”, which are the aspects that Faust is struggling with. Faust, an aging man, will not allow himself to feel a sense of worth or dignity. Faust’s negativity leads him to despair over his state in “Night”. He bemoans his lack of “worthwhile knowledge” (Goethe 371) and disclaims his right to be a college teacher. He is regretful that he has neither money or land, and claims that he has no fame. Yet, when Faust walks among the peasants in “Outside the City Gate”, “Fathers lift boys up” and “all the caps go flying” as the people “genuflect and bend down low” (1015, 19-20). This is certainly a sign of fame, but Faust cannot apply this other’s view to himself because it conflicts with his own self-destructive thinking. This frustration is a result of his negative attitude and persists even in the presence of others’ praise.

While attending the Easter celebrations, Faust meets an old peasant who praises Faust and his father for showing care for the villagers during the plague. “You also did, a young man then, Attend each sick bed without fail” (1001-2). Even Faust’s acquaintance, Wagner, recognizes the peasant’s praise and says, “What sentiments, great man, must swell your breast” (1011). Yet, Faust refutes that he is worthy. He “indicates to Wagner (1026-55) that his ministrations had been futile, that the medicines created by his father had been the product of alchemical experiments that produced poisons rather than cures . . .” (interpretive 356). He lays no claim to heroic deeds or courage, but rather views the attempt at medical care as a decimating failure. His is highly critical of himself and his negative views eradicate any opportunity to be proud of his selfless ministrations during the plague.

Faust’s self-critical attitude extends to his learning of other disciplines as well. He claims that his many years of scholarly study were fruitless attempts to improve his intellect:

I have pursued, alas, philosophy,

Jurisprudence, and medicine,

And help me God, theology,

With fervent zeal through thick and thin.

And here, poor fool, I stand once more,

No wiser than I was before. (354-59).

After all these years, and all this educational effort, Faust feels that he has completed a full circle and has not gained wisdom. His sense of self-worth is so low, it is damaging, as we see in the “Night” scene when he contemplates drinking the poison (735). This unconstructive perception of himself stands in stark contrast to the esteem that a visiting student has for him. The young man comes to seek Faust’s advice about learning and addresses him with reverence:

I have been here but a short span,

And come with reverent emotion

To wait upon and know a man

Whom all regard with deep devotion.

(1868-71).

Not only does the student revere Faust as a learned scholar, but most others do too.

Faust does not have a realistic understanding of who he is, nor what he should be and feels no dignity for who and what he has been in the past.

It is at this stage of confused and distorted self-concept that the Consul and Faust are provided insight into their needs by art. The Consul recognizes his need for alcohol and decides that his relationship with his ex-wife is over through contemplating a prohibition poster called Los Borracones. The Consul carries within his shirt a postcard that “could be a talisman of immediate salvation” for his ruined marriage, yet he is not sure if can forgive his wife’s adulterous behaviour (Lowry 201). That is why he does not reveal the postcard when there is “God’s moment, the chance to agree, to produce the card, to change everything . . . (201). Due to his inability to think straight, he feels torn “like two halves of a counterpoised draw-bridge” (202) and cannot decide whether to return to his marriage or learn to live without his wife. To restore his marriage, he would have to forgive his wife’s adultery and quit drinking. Yet, just thinking about quitting drinking sends him off into his host’s bedroom searching for a bottle.

In the bedroom, the Consul discovers an ancient prohibition poster called Los Borrachones, which provides insight into his own life through the images. Upon examination, he considers the poster “terrifying” (202):

Down, headlong into hades, selfish and florid-faced, into a tumult of fire-spangled fiends, Medusae, and belching monstrosities, with swallow dives or awkwardly, with dread backward leaps, shrieking among fallen bottles and emblems of broken hopes, plunged the drunkards; up, up, flying palely, selflessly into the light toward heaven, soaring sublimely in pairs, male sheltering female, shielded themselves by angels with abnegating wings, shot the sober (202).

The Consul tries to laugh off the image, but then realizes that he has much in common with the falling drinkers. “With shocking surety,” the Consul feels that he is “in hell himself” (203). This realization does not bring him anguish, but calms him as he accepts his situation and gives himself up as lost to the alcoholism. Accepting his drunkenness will allow him to drink without anxiety and is a move into self-awareness.

Having accepted his drunkenness, the Consul can now decide about his wife. His mind wanders to Parián and the cantina Farolito. The idea of sneaking to the Farolito for a drink fills him “with an almost healing love” (203). He longs for the Farolito, where the proprietor is “reputed to have murdered his wife” just as the Consul is murdering the idea of reuniting with his wife. He is consciously making up his mind to release his wife, and allow her to float up to the heavens like the free wives of the drinkers in the image. “A few lone females on the upgrade were sheltered by angels only. It seemed to him these females were casting half-jealous glances downward after their plummeting husbands, some of whose faces betrayed the most unmistakable relief” (203). The Consul is one of the plummeting husbands, relieved to be escaping his wife and the pressure to quit drinking.

The Consul chooses to marry the bottle and take the fall, not to Medusa in the painting, but to the cantina. The Consul admits the cantina is a place of “sorrow and evil” but for him, it is also a place of “peace” (204). The Consul does not believe he is losing his soul, but rather that his “soul is locked “with the essence of the cantina” (204). He may be in hell, but to him, the evil cantina Farolito is surrounded by “the cool pure air of heaven” (204). This decision ends the struggle against his disease and releases a longing that the Consul compares with the feelings of a long absent husband who will soon “embrace his wife” (204). With the help of Los Borrachones, the Consul makes the decision to embrace his alcoholism at the cantina and give up on the salvation of his marriage. He slips the postcard that could have saved his marriage under the pillow on his host’s bed, and begins striving to reach the cantina.

Art is also the trigger that improves Faust’s self worth and sets him striving toward a new life goal. Faust has given himself up to the devil, Mephastopheles, in order to find satisfaction out of life, but Faust does not know what he wants, or what will cure his need to experience more. In the witch’s kitchen, Faust looks into a mirror and sees a rendering of art–an image of a woman so beautiful that he is transfixed. Since his deal with the devil, this is the first time Faust is emotionally struck by any of the “magic”. In the tavern scene Faust found the “magic-mongery abhorrent” (2337). He was likewise unimpressed in the witch’s kitchen, calling it a “hotchpotch of lunacy” (2339). Yet, when Faust sees the image of the beautiful woman, “presumably in the manner of paintings depicting the nude Venus”, he is inspired (370 Interpretive):

The loveliest woman in existence!

Can earthy beauty so amaze?

What lies there in recumbent grace and glistens

Must be quintessence of all heaven’s rays! (2436-9).

This image is a reflection of his own needs, which cannot be sated while he is an old man with a white beard. Through the image’s beauty, Faust is transformed from a despairing old scholar, unsatisfied with his life’s accomplishments into a lusting, rejuvenated man by his mirror vision. “A blaze is kindled in my bosom!” (2461). Strangely, the man who did not feel worthy of praise for his medical or scholarly achievements, now finds himself worthy of Venus. This shows the randomness of Faust’s self-worth as is swings from desperate, suicidal lows to encouraging, narcissistic highs. The vision of Venus has given Faust a goal to strive toward–that of ideal beauty. The image establishes . . . the erotic as a legitimate aspect of Faust’s essential striving . . . (Interpretive 372). With a new direction in which to pour his energies, Faust is motivated to drink the vile witch’s brew and complete the transformation so that his body matches his newfound spirit. Now Faust knows what he wants out of his deal with Mephistopheles, and Mephistopheles knows what might fulfill the deal. This search for ideal beauty and Faust’s new-found dignity will lead him to Gretchen, Helen of Troy and eventually embolden him to “beautify” the earth by damming up the sea. Both seem to be lacking an awareness of themselves, seem to be lost in that adolescent quest of finding the way, their worth and their place in the world.

Works Cited

By V.S. Ramachandran THE NEUROLOGY OF SELF-AWARENESS [1.8.07] Edge http://www.edge.org/3rd_culture/ramachandran07/ramachandran07_index.html July 24, 2008

Gwendolyn Richardson In Search of Self: Adolescent Themes in the Twentieth Century Short Story Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute

http://www.yale.edu/ynhti/curriculum/units/1983/3/83.03.02.x.html

Roed, ENGL401 Study Guide

Lawrence, Greene and Lowry: The Fictional Landscape of Mexico

By Douglas W. Veitch, Published 1978, Wilfrid Laurier, University Press

The Old Man: A worthy foil to Mephistopheles in Dr. Faustus

Does access to unlimited knowledge and pleasure make you strong in character and faith? Christopher Marlow answers this question in his morality play Dr. Faustus. Faustus is a scholar who is consumed by the desire to experience life to the fullest and know more than his 16th century society can teach him. He turns to Lucifer to fulfill his needs, trading his soul for the ability to work magic and for access to worldly knowledge. The play features many characters who attempt to influence Faustus, for better or worse. The characters are divided into camps of good and evil–a good angel and a bad angel are two voices in Faustus’s ears. Another contrast of characters is Mephistopheles and the Old Man. Mephistopheles is the ambassador of evil, working directly under Satan himself. His character is second in significance only to the role of Faustus, while the Old Man makes few appearances. It is the Christian spirit of the Old Man that makes him a worthy foil to Mephistopheles, not the number of lines written into the play. The Old Man functions to remind the audience that faith in God is more valuable than worldly knowledge by withstanding the torments that Faustus succumbs to.

Without fear for himself, the Old Man enters a room where Lucifer’s right hand demon, Mephistopheles is and encourages Faustus to break his contract with Lucifer. After twenty-four years of exercising his evil powers for personal gain, Faustus is hosting a farewell feast for his friends. The end is near and Faustus will soon have to fulfill his bargain by giving up his soul. Faustus has refused to repent many times in the play, but the Old Man offers to guide Faustus along the “sweet path” of “celestial rest” (5.1.36-37). Mephistopheles hands a dagger to Faustus to encourage him to use it on himself, but the Old Man prevents this by giving Faustus hope:

Ah stay, good Faustus, stay thy desperate steps:

I see an angel hovers o’er thy head,

And with a vial full of precious grace,

Offers to pour the same into thy soul. (5.1.52-55)

The Old Man is in a battle with Mephistopheles in attempting to convince Faustus to repent. Even though he recognizes that Faustus has committed “flagitious crimes of heinous sins” and that the devils can punish him for trying, he still offers Faustus the mercy of the “Saviour” (5.1.43.45). Faustus, for all his twenty-four years of access to the pleasures of the world, is weak in his faith and his character and still cannot choose between good and evil. Yet, the Old Man shows incredible fortitude of character in standing off against Mephistopheles in a battle of persuasion and does not abandon Faustus.

The Old Man’s faith in God is backed by knowledge of the scriptures, which he uses to strengthen his persuasive power over Faustus. The Old Man’s words mirror Joel’s speech to the people of Judah in the Old Testament. Joel explains that the people can still avoid calamity through repentance. “Even now,” declares the LORD, “return to me with all your heart, with fasting and weeping and mourning. Rend your heart …” (Joel 2:12-13). The Old Man claims that Faustus can still avoid eternal torture through repentance. He also mentions weeping and heartbreak when he encourages Faustus to “break heart, drop blood, and mingle it with tears, tears falling from repentant heaviness” (Marlow 5.1.38-39). Faustus, with the knowledge of the world at his beck and call for twenty-four years is not able to think his way out of the situation he has created. But the Old Man’s use of scriptural terms in his speech adds weight to his claim that Faustus can still save himself, and with words he is able to encourage the Doctor to consider repenting.

Faustus’s tragic lack of spiritual strength is emphasized by the strength of faith that the Old Man displays. Even at the point of facing the terrifying conclusion of his bargain with Lucifer, Faustus is unable to turn to God for forgiveness. Faustus begins to repent, but begs Lucifer’s pardon when Mephistopheles threatens to tear his flesh into pieces. “Thou traitor, Faustus, I arrest thy soul, for disobedience to my sovereign lord. Revolt, or I‘ll in piece-meal tear thy flesh!”(5.1.66-68). Faustus immediately recants and offers to “confirm” the “former vow” with his blood (5.1.72-73). He is too spiritually weak to grasp at his last chance for salvation, yet the Old Man’s faith is strong as he faces the same physical threat that defeats Faustus. Faustus sets the devils upon the Old Man when he orders Mephistopheles to torment “that base and crooked age, that durst dissuade” him from Lucifer (5.1.76-77). Unlike Faustus, who sees the threat of the devils as a reason to turn from God, the Old Man sees the approach of the devils as a test of his faith by God and this gives him strength to endure.

My faith, vile hell, shall triumph over thee!

Ambitious fiends, see how the heavens smiles

At your repulse, and laughs your state to scorn:

Hence hell, for hence I fly unto my God.

(5.1.116-119)

The Old Man’s strength in the face of the same threat of physical violence that was made to Faustus, shows the audience how weak Faustus is. He is a figure to be pitied.

Faustus is revealed as a tragic figure when the audience realizes that the Old Man, without the worldly knowledge that Faustus has traded his soul for, is stronger in character and in spirit than the Doctor. Marlow’s play reminds the audience that moral strength and spiritual faith, as displayed in the Old Man, are more valuable than worldly knowledge and experience. The Old Man is able to use his knowledge of the scriptures and his strength of character to attempt to rescue Faustus. He uses his faith to withstand the torture of the devils, believing his reward will be eternal bliss. Faustus reveals the depth of his weakness when he cannot repent, even with the Old Man’s help. The decision should be easy–Faustus has nothing left to gain by his pact and everything to lose. Tragically, Faustus’s weak faith leaves him a pawn for the devils who will have his body and his soul to torture. With the rending of Faustus’s limbs, the play delivers the moral lesson. The audience is left respecting the Old Man and his faith, and pitying Faustus and his desires.

.

Works Cited

New International Version Scripture taken from the HOLY BIBLE, NEW INTERNATIONAL VERSION®. Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984 International Bible Society. Used by permission of Zondervan. All rights reserved. http://www.biblegateway.com/passage/

Marlowe, Christopher. “The Tragical History of Dr. Faustus.” The Longman Anthology of British Literature. Volume One. Ed. David Damrosch. New York: Addison-Wesley, 2003. (1143-1191).

The Hypertext Fiction Ride: Using structural metaphor to enhance fiction

We learn categorization of information and objects as early as preschool, so it is reasonable that we would compile information into categories on the Internet. Traditional Web site structure is hierarchical. The Web address takes the visitor to the top or opening page through which the other site pages can be accessed through navigational categories. Business information is often grouped under common category headings, such as “about us”, “services”, “contacts” and “rates”. Personal information is often categorized under personal, family and career topic headings. These headings are available to the Web site visitor in the form of navigational links, which when clicked, take the visitor to the page or lexia of information. This sorting of information into categories makes the data accessible as the site visitor intuitively understands the structure. It also allows the visitor to make quick decisions about which information is important and to act by moving directly to the lexia hosting that information. Interface and browser design has evolved with this accessibility or “user friendly” goal in mind (Sanford). JavaScript, Cascading Style Sheets and HyperText Markup Language offer all manner of layout, communication and navigational options. Browser windows feature forward and backward directional navigation buttons and the windows are square, fitting neatly into square monitor screens. But with all boxes, there are those who would move outside and challenge the visitor to understand information through a new form of organization. Authors of hypertext fiction are utilizing code and browser options to enhance their narratives with movement. The options for visitor interaction provide the reader with unique, interactive experiences that compliment the story, but these interactions are not always navigationally intuitive. By using navigational options of interface design to control the movement of their readers, hypertext authors enhance the reading experience, emphasize their themes and create structural metaphors of their texts.

Though navigational options offer all manner of movement, some authors of hypertext fiction present their writing in a linear structure by forcing the reader into a controlled trajectory. Just as we intuitively navigate categorized information, we understand that Western, print-based narrative fictions are meant to be read in a linear fashion, from the first page to the last. The introduction of setting, characters and the design of plot are all part of this linear organization. “Hyperlinked fiction, unlike the larger network of the web, draws its narrative inspiration from the print-based novel …” (Guertin 8). The traditional linear structure of the print-based novel is evident in “this is Not A Book” hypertext by Jennifer Lay and Thomas Swiss’s “City of Bits”. Both hypertexts pop-up in a size restricted window and offer only one form of navigation—forward. Lay uses hyperlinks or navigational words imbedded in the text, and Swiss uses a graphic link of a man walking. When reading a print-based book or a poem, a reader can turn back through the pages or reread the stanzas, but not so in Lay and Swiss’s hypertexts. The pop-up windows are modified so that there are no back button options, though the web address is visible. The reader can see each page’s URL change from book3 to book4 or, as in Swiss’s case, page1 to page2, which is a clear indication of the linear structure of the texts. This linear structure is recognizable to the reader, but discomforting to the web site navigator who may become frustrated with the lack of autonomy. Like tunnels, there is only one way in and one way out of these hypertexts. Choice of information access has been taken away through the removal of hierarchal navigation menus and browser buttons, and the reader moves along in a site-propelled straight line. It is only through the reading that the reader realizes the purpose of the straight-line navigation.

This straight-line navigation in “City of Bits’ is symbolic of the poem’s theme that we cannot turn back time, cannot go back and change the past. “In electronic narratives … the interface is designed anew for each text with the metaphor being specific to the content of that particular work” (Guertin 28). Swiss’s poem is a walk along memory lane–a reminiscing about a relationship that took an unexpected turn. The narrator has to move on in life, no matter how much he wants to return to his ex-girlfriend. “I admit it: I missed her. Ah to be drinking again at that downtown river-front hotel… “ (Swiss). Just as the narrator must move forward with time, with no control over the ending of the relationship, so too must the reader plod ever-forward, with no hope of controlling the journey through the hypertext. Swiss successfully uses this tunnel-like navigation to create a sense of helplessness in the reader, which supports empathy in the narrator’s situation.

Jennifer Lay uses the restricted tunnel movement to build drama in “this is Not A Book”. Each lexia in Lay’s text features one line, which argues the difference between traditional print novels and hypertext. The first point is that the reader “cannot turn” the pages in Lay’s “Not a Book”. In another lexia, the narrator tells the reader that the text is not “interested in becoming a book“. This reference to the text’s lack of interest could imply artificial intelligence, or perhaps it is just simple personification, but either way the image of the text changes in the reader’s mind from a programmed reading to a thinking entity. The personification effect is continued when the narrator explains that the hypertext “has no intention of superseding the book”. The hypertext is not interested in competing with the printed book. It is interested in the reader. The text refers to itself as a piece of artwork that will imbed itself within the reader’s subconscious—a design that may “glimmer” under the reader’s lids long after the reading. The tension rises as the text states that the hypertext may call the reader back, like a “phantom” limb tempting a revisit. It threatens to evolve as if it can work its own advancement within its technological environment. With these words the spark of fear, the underlying paranoia created by Hollywood films of technological takeover bubbles beneath the surface and mixes with curiosity. The writer continues climbing the rising action with the allusion that the reader is not reading a book, but is being observed by a text. “… it knows you are here, now”. This is the climax, the moment of change and the reader pivots on the peak before clicking the hyperlink that leads to an invitation to communicate with the “Not a Book”. Lay’s control over the reader’s progress through the text ensures the rising sense of drama and suspense. Without this linear trajectory, the emotional effects of the “revelations” would not be as powerful. Each disclosure invites the reader forward to see what the next shocking claim may be. The experience is not about believing the text, it is about the “ride”. The suspense-building narrative draws the reader ever-forward, just as a rollercoaster pulls the cars up a linear track to the top of a hill. At the crest of the hypertext, there is the option to communicate, which leaves the reader suspended in a world of possibilities—overlooking the “park” of tomorrow’s hyper-entertainment.

Just like any entertainment complex, which features rides of multiple movements, hypertexts can be created using multiple structures. Not all hypertexts force readers along a straight path, because not all hypertext fictions are restricted by linear plots. Like print-based autobiographies or domestic stories, hypertext can be presented in an episodic format. “’my body’: A Wunderkammer” by Shelley Jackson uses the episodic structure of the domestic story combined with data archived under body-part categories to present her autobiography. One element of autobiography that is not evident is a chronological structure. “This is a messy text. It shifts back and forth through time, following the associational trails of recollection” (Guertin 25). The reader is in charge, selecting which hyperlinks to explore and so the text is delivered based on the navigation of the reader and the writer‘s placement of hyperlinks. The main navigation page consists of a drawing of the author’s body, which is blocked into graphic links to pages file-named “armpits” and “tattoos”. Once into the pages, movement is achieved through clicking hypertext links imbedded within the text. The reader is tempted by the hyperlinks to leap out of each page before finishing and may often land on a previously visited page. The navigational movement begins to feel like a journey impeded by attention deficit. Unlike the well directed reader of Swiss’s “City of Bits”, the reader of Jackson’s hypertext is allowed the freedom of travel with few boundaries or guidance. This does not mean that the writer has not left crumbs to follow. Clicking a blue hyperlink that leads to the “toes” page, does change the colour of “toe” links to a “visited” purple on all of the other pages. The aware reader could take control of the access of information through this and through reading the task bar Web address when hovering the mouse over a link. Through the categorizing of the hypertext information, the reader, with the right knowledge of data archiving and interface design, could navigate intuitively in avoiding visited pages. Either way, without a main navigation listing of categories or pages, the reader explores the texts randomly, without knowing how many pages have been viewed or how many are left.

This lost exploratory may be the effect that Jackson is looking for. “I will hide secret buttons, levers and locks in my carved folds and crevices. You will have to feel your way in” (Jackson). The reader explores stories of Jackson’s body like moving through a funhouse. Thrilled and sometimes horrified by the text, and moving from reading to reading through random clicking of links—the reader never knows what will be beyond the next click and often gets turned around. “Once I have entered her network, by means of an orifice, I am contained and I am captured” (Wodtke). The author’s relationship with her physical self and the changes she goes through is enhanced by the reader’s exploratory movements, creating a sense of a shared experience. The lack of control in navigation is symbolic of the lack of control over pubescent changes, which is a topic in Jackson’s text. There is a certain horror to not being able to control growth as well as movement and the reader, through the random navigational journey, can relate to the author’s feelings of being out of control.

Hypertext is a medium by which authors can elicit connections in their reader’s through navigational movement. By utilizing interface and database code and browser features, authors can metaphorically represent their themes, providing readers with richer experiences and connections. Through linear movement, Lay builds suspense and Swiss makes it clear that there is no turning back in life. Through random movement, Jackson creates an exploratory space that symbolizes the discovery of body and curious changes of pubescence. As hypertext structures continue to be creatively paired with theme, plot, and literary structure, readers will learn to experience the movement based on the reading and not on an efficient categorizing of information. Through hypertext, the writer has become the ringleader who will create an entertaining interaction for the reader to experience and enjoy.

by Cheryl R Cowtan

English 475

Professor Joe Pivato

June 22, 2008

Works Cited

Guertin, Carolyn, Tschofen Monique and Totosy de Zepetnek, Steven. English 475: Literature and Hypertext Study Guide. Athabasca University, 2002.

Jackson, Shelley. “my body”’: A Wunderkammer.” Online hypertext. <http://www.altx.com/thebody/>

Ley, Jennifer. “This is Not a Book.” Online hypertext. 2000. <http://www.heelstone.com/notabook/>

Swiss, Thomas. “City of Bits.” Online hypertext. <http://www.differenceofone.com/cob/>

Wodtke, Francesca. “Erythrocytes: Flowing through the Body. A metaphor for Hypertext: The Body—Within.” Cyberspace, Hypertext and Critical Theory. Brown University. Online. <http://landow.stg.brown.edu/cspace/pg/wodtke.html>

Hypertext Fiction: It’s natural for a reader to follow an associative path

Long have fiction readers succumbed to the imagery of settings, empathized with characters and thrilled along the plot line of introduction, climax and resolution. Absorbing words and turning pages, fiction readers followed a linear path that was carefully constructed by authors to fit the format of the printed book. This has been the way of the story since printing conventions were established–the author writes, the reader reads. Then there was light, and binary code and the transportability of text was discovered. Writers mixed storytelling with technology that made “possible nonsequential, fully electronic reading” called hyperfiction (Snyder). With hyperfiction, readers were woken from a long period of active reading in which they made mental connections, to find they had to make active decisions to move through a story, following trails set by authors in underlined words. Readers experienced frustration, elation and cast off their linear expectations of plot as they were gently guided into interactive reading. The role of the reader turned on a link and a new form of story was born; one which demanded more of the reader through discovery, interaction and a casting off of linear plot expectations.

Hyperfiction calls to the adventurous soul, tempting the reader to discover the unmapped organization of its structure. By clicking hypertext links, readers can choose to explore within the story or move out into other texts that are related in content. Unlike printed fiction, the hyperfiction expands and stretches its storylines in many directions offering the reader bridges to cross and fjords to leap. “The space we seem to be manoeuvring is “imaginational.” Like bugs in flatland, we momentarily extend the traditionally linear (i.e., 2-D) reading act into a third dimension when we travel a link” (Tolva). The reader, like a true adventurer, must often leap blindly for the links seldom denote where she will arrive. These transporters are not navigational buttons that follow an ordered categorization of content. The hyperlinked paths have been created by the author to enhance the effect of the text, just as a gardener creates a path to lead the stroller past the brightest rose, the trickling waterfall.

In M.D. Coverley’s hypertext, Califia, the reader must traverse multiple histories by exploring letters, pictures, deeds and journals. The text is rich in clues, secrets, puzzles and quests, but it is also of value to the reader as she learns to enjoy the content without resolution-oriented consumption of words. “The reader must ramble and be sidetracked in Califia because all narrative lines are visual, fragmentary and nonsequential–and yet all are interlinked associationally across time and geography by the constant of the quest for treasure” (EnGL32). The quest and the discovery hold the reader to this complex text, which could take days to traverse. We are “satisfied when we manage to resolve narrative tensions and to minimize ambiguities, to explain puzzles, and to incorporate as many of the narrative elements as possible into a coherent pattern” (Yellowlees). Unlike plot driven stories, the discovery in hypertext is often the journey, and the journey is powered by the reader’s willing interaction with the text.

In Hyperfiction there can be a plot, or multi-plots, so the reading path is not as obvious as in a printed book, therefore, the reader must consider the route.

Any individual path through hypertext is linear, of course: the reader is still reading or viewing or hearing items in sequence, which is to say, one after the other, linearly. What makes hypertext hypertext is not non-linearity but choice, the interaction of the reader to determine which of several or many paths through the available information is the one taken at a certain moment in time. (Deemer)

Reading through one page, the reader must decide whether to move to another or continue reading. The reader can open text in multiple windows, move off text into researching forays, and sometimes movement decisions are retracted through back and forward button clicking. The hypertext environment “… is characterised by fluidity, and enables an interactive relationship between writer and reader” (Snyder 3). Hypertext is not still, the reader must scroll the text up or down, load and refresh and move between lexias, and the movements begin to reveal the structure created by the author. How the text is ordered and filed on a server becomes more clear and with it, sometimes the intent of the author. As the reader journeys, the structure becomes distince, the reader is experiencing two texts: the story as written in hypertext and the structure as written in code.

Hypertext requires the reader to cast off the literary conventions built over centuries of reading linearly organized and categorized information. To truly enjoy and benefit from hypertext, the reader must not restrict the experience by comparing it to printed works. The flexibility offered by Web and software design frees the author to create outside of the traditional print structures. “…hypertext authors are able to fabricate texts that more closely resemble the freely flowing associations of the human mind” (English Study Guide 55). But, readers have been trained to read paragraph to paragraph, and may be frustrated to encounter different structures in text. “Hypertext disturbs our linear notion of texts by disrupting conventional structures and expectations associated with the medium of print” (Snyder 17). Lexias that refresh before the reader is finished reading or multiple links that lead back to the same lexia can be irritating to readers who expect the plot to plod ever-forward over climax and onto resolution from page one to twenty-one.

Stuart Moulthrop’s “Hegirascope” is a hypertext to bring a reader’s frustrations to the fore as the document moves on without waiting for the physical cue from the reader. Just like a beach wind that ruffles the pages in a printed book, the lexia will refresh on the reader moving her to another page of content. Yet unlike a bound book, each page is populated with one to four links and the choices lead into multiple stories. The reader must open her mind to the multiple “threads” and realize that she is traversing a new structure and therefore, new experiences. “… hypertext fiction helps underscore the limitations of traditional forms of closure and elicits new forms of pleasure, pleasure not from the inevitability of an ending, but from the multiplicity of openings” (Closure). Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari refer to a “networked root” as a metaphor for the structure of hypertexts (ENGL 29). The root or rhizome structure offers the author the option of writing multiple storylines, which increases the opportunity for multiple points of view. Where a print novel may relate the story based on a first-person narrator, a hypertext fiction could allow the reader to jump back and forth between multiple narrators, experiencing the perspective of many characters. “Electronic fiction … privileges a multiplicity of voices and information over plot … The reader is doused in a babble of voices and must separate the threaded points of view to assign order and intent to events in the text” (Engl475 29). The multiple voices cry out that there is more than one truth and the reader must actively absorb all perspectives of the event, juggling them in his or her mind in order to make sense of the reading. This active consideration of multiple narration draws the reader ever-closer to the author and the creative process (Murray 40).

The reader is also drawn into the creative process by the multiform story, as the reader must consider multiple possibilities in plot. According to Janet Murray, the multiform story “presents a single situation or plotline in multiple versions” (30). Reading a multiform story reminds the reader of the author as reader is pulled out of the immersive state that a single plot line might incur. “When the writer expands the story to include multiple possibilities, the reader assumes a more active role…”( 38). The reader may wonder at the author’s choices, or lack of a choice in sticking to one plotline, and the reader must keep all plotline options organized in his or her mind while reading.

Readers of scrolls, manuscripts and books have always read in an active manner, absorbing the story, making predictions, and making connections. Hyperfiction extends this active reading to an interactive participation in the structure of narrative as the reader makes choices about the paths of the reading. As the reader manipulates the computer, windows and pages the experience of the hyperfiction moves past the need to find resolution in plot to an enjoyment in discovery. The exploration of structure reveals the hidden text–the author’s intent in the code and the creative process comes to mind of the reader to grow with the fictional experience. Hyperfiction, through the use of link travel, can send the reader into a new experience where she takes on the role of discoverer. The reader is reborn as she casts off the design to follow the linear thread and opens her mind to the associative thinking that is natural. Her role changes, turning on the click of a link.

Written 2008 by Cheryl R Cowtan for York U Hypertext Course

Works Cited

Coverley, M.D. Califia. Watertown, MA: Eastgate Systems, 2000. (CD-ROM for PC).

Deemer, Charles. “What is Hypertext?“ (1994). 6 Jul.2008. Online. <http://www.ibiblio.org/cdeemer/hypertxt.htm>

Douglas, J. Yellowlees. “‘How Do I Stop This Thing?’: Closure and Indeterminacy in Interactive Narratives.” Hyper/Text/Theory. George Landow, ed. Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore and London, 1994.

Guertin, Carolyn, Tschofen, Monique and Totosy de Zepetnek, Steven. English 475: Literature and Hypertext. Alberta: Athabasca University 2002.

Jackson, Shelley. “My Body – a Wunderkammer”. My Body – a Wunderkammer. N.p., 1997. Web. 27 July 2016. <http://www.altx.com/thebody/>

Keep, Christopher,Tim McLaughlin and Robin Parmar. “Closure.” The Electronic Labyrinth. Online. <http://jefferson.village.virginia.edu/elab/hfl0286.html>

Moulthrop, Stuart. “Hegirascope” Version 2. New River Vol 3 (October 1997). 5 Jul. 2008. Online. <http://iat.ubalt.edu/moulthrop/hypertexts/hgs/>

Murray, Janet H. Hamlet on the Holodeck: The Future of Narrative in Cyberspace. New York: The Free Press, 1997.

Snyder, Ilana. Hyperfiction: its possibilities in English. 5 Jul. 2008. Online. <http://www.schools.ash.org.au/litweb/ilana.html>

Tolva, John. Ut Pictura Hyperpoesis: Spatial Form, Visuality, and the Digital Word (1994). 3 Jul. 2008. Online. <http://www.dilip.info/HT96/P43/pictura.htm>

June 1, 2017

“Big Eyes” Witnessed it all – The Conning of Margaret Keane

As a young girl, I had two Keane paintings hanging in my bedroom–the harlequins with the multi-coloured dresses and the mandolins. I spent many hours staring at the harlequin’s big eyes, and basking my young brain in the colours of the paintings. Little did I know, the artist who had painted them had been mistreated and bamboozled by her husband for 10 years.

“If you want me out of your life, you’ll have to paint me 100 more waifs–100 more Keanes”.

How does it happen? How can someone take over your art, your heart’s-work, and pass it off as their own and you just let it happen? If you’ve ever wondered how people get themselves stuck in situations that don’t serve them, and often harm them, you need to watch the movie “Big Eyes” on Netflix.

The film is based on the true story of Margaret Keane, artist of the “big eyes” waif portraits. For 10 years, her husband claimed he was the artist who created her work, and though he couldn’t paint, he was a genius salesman and was able to make quite a bit of money and gain a lot of fame through his sales skills. Walter never painted a thing. His wife produced all the paintings for him to sell, often working herself to sleep in a small studio in their house. Even Margaret’s daughter was lied to.

The film succeeds, for me, in the way it shows the viewer step-by-step, how a person can be conned, abused, tricked, coerced, and finally become so immersed in a lie, they can’t find their way out. The movie shows us something else, how isolation, suppression and a patriarchal society can lead to the mistreatment of women. It was the vulnerability of Margaret being a single mom in the 1950 and 60’s that lead to her being taken advantage of, and when she tried to seek religious counsel, she was advised to recognize her husband as the decision maker and man of the house.

Beyond these serious social issues, the film is very entertaining. The conn skills of Walter are incredible, right down to the end, where he still maintains he was the artist. So, as a character study, it’s brilliant. As a true story, it’s eye-opening.

Protect your work. Protect yourself. Truth will never steer you wrong.

January 3, 2017

“Targeted” is a tightly paced thriller

“Targeted” is a tightly paced thriller that takes place at a Honduras resort where Canadian tourists, Jordan and Ellie arrive, hoping for peace and relaxation.

The story’s tension starts the minute the girls exit the plane to stand, unknowingly, in the view of a character peeping at them through binoculars. His glance lingers “on the swell of fabric above [Ellie’s] bare midriff”. We know the peeper is up to no good when “the scarlet blossoms shudder” as the binoculars are withdrawn back into the bushes.

On the way to the resort, the girls meet Darcy Piermont, a character I hope we’ll see in a future novel. Darcy is a handsome mishmash of uncouth manner, with a devil-may-care-attitude, who surprises readers with occasional glimpses of gallant capability. He is the first to warn, “Honduras has the highest murder rate per capita in the world. So don’t wander away…”

What happens next, would be a spoiler, but let me say, as you read on, you will consider all those risky choices you made while on vacation. I certainly reflected on the time I wandered alone in the Dominican and found myself lost in a very poor neighborhood where some not so friendly looks were cast my way. Though I was directed back to the areas for “tourist’s eyes” by three tattoo bearing, young men who stood like sentinels on the street, I had the feeling I had brushed against the outer edges of danger.

In the novel, Jordan and Ellie do not take Darcy’s advice and will do more than just brush those fearful realities where human rights are not what we Canadians are privileged to.

This book succeeds in a number of ways. The authors, Warner and Ferris, are obviously well traveled and use description to immerse us in a much-needed island getaway with limbo dancing and boat deck parties in international waters. These fun-loving scenes function as clever juxtaposition to make the threat against the women even more chilling.

Secondly, the two female characters could not be more different, with cool-thinking Jordan wishing she was wearing her service revolver with her bathing suit, and fun-loving, barely-keeping-her-clothes-on, Ellie who is getting her money’s worth from the all-inclusive drinks. The girls have an interesting and amusing dynamic as they work as a team, whether in navigating social pick-ups or attempting to survive criminal highjacks.

“Targeted” is an entertaining book that could easily be read on the journey to your next island vacation, but be warned, you’ll be looking over your shoulder after you’re done.

December 16, 2016

Characters with Inner Conflict are just too Juicy!

“I was tempted to deny I was capable of gutting and skinning him, but I had killed before.”

Who would say such a thing? Well, the tortured main character of my first-in-series novel, “Girl Desecrated”, of course. And if I wrote Rachel’s struggle correctly, the reader should be wondering if she’s going to gut Donald, the American, or not.

[image error]Rachel is consumed by a constant battle of wills against her alternate personality, who unfortunately, likes to hunt people. With the help of medication, her incredible strong will-power, and a strict rule regime, Rachel mostly keeps the other personality subdued. But sometimes, the She erupts, and then all hell breaks loose. Rachel’s battle is what literary geeks call internal conflict because she is fighting herself. (Pssst, I’m a literary geek).

A battle within oneself is internal conflict, and mental health is just one example of how a character can be internally divided. Another example of internal conflict is opposing morals. Take for instance William Cain, lover to Rachel’s “other” in “Girl Desecrated”. He’s a good man, isn’t he? And yet, the thoughts that run through his head are not the thoughts a good man should have…

[image error]

In contrast to the dark grain of the coffin, her skin shone alabaster white, unflawed and as smooth as marble. And her mouth… My fingers twitched to trace those lips that were still full and dark like wine. Closing my eyes, the memory of the feel of those lips on mine caused a heady rush. My loins warmed beneath my funeral pants, jolting me to an awareness of my surroundings with a horrific sense of shame.

Gritting my teeth, I contemplated the magnolia’s grey trunk to defuse my passion. Dark with rivulets of rain, the trunk was as much a betrayer as her lips. For it too took me back to the recent past. It had been a silent witness to my hands gripping its bark above Scarlett’s hair as I had turned her mouth into a little circle of surprise with my heated thrusts.

Fantasizing about a dead woman at a funeral? That’s just nasty. And definitely something a God-fearing man should be ashamed of.

Notice how the character swings between his desires and his horror at the inappropriateness of those desires. This back and forth creates tension as we read, because we’re watching a struggle, and we don’t know whether he’s going to get his perverse thoughts under control before the people attending the funereal discover his dark preoccupation.

Another example of internal conflict is when the main character knows they should do one thing, but they want to do another. This is where the author can bring in low self-esteem, guilt, compulsion, etc.

Generally the root of the conflict leads to choices the character has to make, choices between good and evil, or appropriate and inappropriate, or healthy choices vs unhealthy choices. The trick is, the choice has to be something the character would not normally do or admit to. That’s where the deep soul torture comes in. This kind of torturous decision making, “should I?” or “shouldn’t I?” creates delicious tension in the reader, as they wait to see if the character can overcome the part of them that is causing problems.

It only took me ‘til six to burn through the last of my birthday budget. I cast a look around the pub. It was the first time I noticed the people sharing my space since I’d arrived. A few men were perched on time-scarred, wooden stools along the bar, regulars by the look of their defeated posture. Experience had taught me men are cheap and easy, so it wouldn’t take much to get a free beer. Normally.

Problem was, I had made a birthday resolution to not have sex or engage in any physical interactions or altercations with members of the male gender for one week. Sounds a little uptight, but those are the exact words Patrick used before pressuring me to agree.

Patrick tricked me into agreeing, really. He knows how much I want to get better and go to college. He felt it would be a helpful part of my therapy to swear off men for a week. He seemed to think drying out the well so to speak, would almost cure me. That seemed a little farfetched, considering my psychiatrist thought I was certifiably crazy, but hope is a valiant chum. And I needed all the help I could get, even if it was from my mother’s male nurse at the Homeward Sanitarium.

This example keeps the readers’ attention because they want to know if the character will stick to her promise to Patrick or offer herself up to a bar-goer in exchange for free drinks.

Internal conflict doesn’t work well alone. In “Girl Desecrated”, the “other” Rachel battles for control is named Scarlett – Scarlett does bad things when she gets out, and this is where the action comes in. When Scarlett is “out”, the conflict becomes external, because Scarlett has much different morals than Rachel. Scarlett treats people badly. Rachel has been treated badly. Sometimes they blend into each other, but Scarlett doesn’t get nicer… Rachel only gets meaner.

Except Man-boy. He was standing at the end of the table gazing wistfully at me, waiting for a reward for his gallant, if failed, attempts to intervene on my behalf. An impulse to crush his self-esteem, to make him pay for being the same gender as Donald, tempted me.

But that was my bad side, and I wanted to stop listening to my bad impulses. My psychiatrist, Dr. Casbus said I shouldn’t be cruel to others, no matter how much I’ve been hurt.

“Thanks for having my back,” I offered, generously, then instantly regretted it as he reached for a chair.

When Scarlett is in control of their shared body, she has effectively become the antagonist, and Rachel must battle her to stop bad things from happening, and to get control back.

But wait… if Scarlett is an alternate personality, isn’t that inner conflict? Or can a novel have two types of conflict for the protagonist?

Internal conflict generally presents less action than external conflict, unless of course, the inner conflict can be matched up with external conflict. Consider “Lord of the Rings” and Frodo. The ring is external. The weakness of “man” and Gollum in so quickly falling for the seduction of the one ring is character flaw. But the battle Frodo goes through in resisting the temptations of the ring is internal, partly because we go through it with him, and because it is a drawn out torturous journey.

A second example is Katniss Everdeen in “The Hunger Games”. She’s living as an oppressed person in a world where there is a power imbalance. Normally, she would follow the rules, but the rules are not fair, and in order to feed her family, she hunts where she is not allowed to. However, she’s not a total rule-breaker and limits her rebellion to overcoming the “external conflicts” she and her family cannot survive, like starvation. Once in the games, she has to decide whether to kill. That’s an internal conflict, even though the external pokers are that she will be killed if she doesn’t fight.

Internal conflict can be created in a character through any number of stressful inner battles, from moral and religious standards, to poor relationship skills, to guilt, low-self worth, poor communication skills, mental health issues and personality traits.

The internal conflict works for a novel when the reader is encouraged to follow the conflict through to see how the character will resolve it, or be beaten by it. As an author, play it tight to the character and make it seem as if the characters themselves don’t know what’s going to happen either.

As a reader, just enjoy the juicy ride of internal conflict!

__

The above excerpts are from “Girl Desecrated” the first novel in “The Fergus She” series, which is available here. Click through to read more free chapters and see how Rachel fares in her battle against herself–the Scarlett.