L.E. Carmichael's Blog, page 9

April 28, 2023

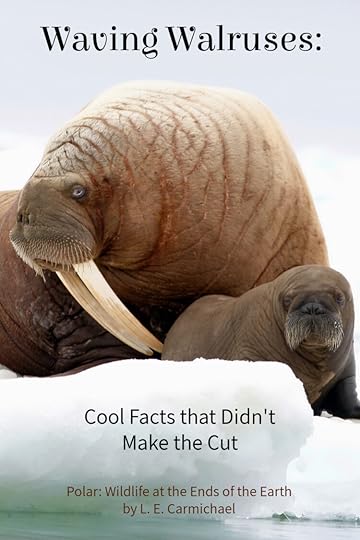

Waving Walruses: Cool Facts that Didn’t Make the Cut

Four more sleeps until Polar: Wildlife at the Ends of the Earth lands in a bookstore near you!

Four more sleeps until Polar: Wildlife at the Ends of the Earth lands in a bookstore near you!

During preliminary research for the book, when I was trying to figure out which adaptations I would cover and which animal from the Arctic would be paired with each animal from the Antarctic, I came across a weird fact about walruses that totally tickled me – until I realized there was no place for it in the book. Fortunately, there is always room for weird facts on this blog! So let’s take a look at feeding behaviours of Atlantic walruses. Specifically, those in Young Sound, off of North East Greenland.

What Do Walruses Eat?Walruses are benthic feeders, meaning they forage for food on the bottom of the ocean. They love bivalves – molluscs such as clams that have hinged shells – and there are three specific species that they will choose when given the chance.

Like all marine mammals, walruses breath air, and they can only stay underwater for about 10 minutes before they need to take another breath. So they usually forage in mollusc beds that are between 1-6 m below the surface. Short travel time means they can maximize feeding time before swimming back to the surface.

And it takes a lot of molluscs to feed a walrus. One study found the remains of 6400 molluscs in a single walrus stomach! A male walrus that weighs 1226 kg eats about 74 kg of mollusc tissue per day. They spend 13 to 14 hours out of every 24 searching for food.

How Do Walruses Hunt?Scuba diving scientists hung out in the water, filming walruses as they fed. The ocean bottom of Young Sound is sandy, and feeding stirred up a lot of sediment, so scientists couldn’t tell exactly how the walruses were getting molluscs out of their shells. But they did get great views of how walruses go about finding prey that can be buried up to 40 cm deep.

And they shared the videos! For copyright reasons I can’t embed them here, but the videos are available online for free. Hop on over to the webpage for the original research article. In the right-hand menu, click on Electronic Supplementary Material. You can download the files and play them on your computer as often as you want.

Speaking of right-hand… but I’m getting ahead of myself.

According to the study, walruses dive to the mollusc bed and settle with “their tusks resting like a sledge on the bottom.” Wear marks caused by dragging their tusks along the sand were clearly visible when the walruses were hauled out on shore!

Walruses face into the ocean current, so that the moving water pulls stirred-up sand away from their eyes. They appear to be looking for food with their eyes, as well as feeling for it with their whiskers. And they use three strategies for locating tasty niblets:

Using the whiskers on their snouts to feel for buried foodSquirting a water jet from their mouths to blast away sandWaving a flipper over the seabed to sweep away sandThe waving method is the most popular. And – apologies to any human lefties out there – walruses are right-handed! They wave with their right flippers 89% of the time. No single walrus preferred to use its left flipper. Granted, this was a small study of only a handful (ha!) of walruses, so it’s possible the lefties are out there. But either way, the very notion that walruses might have a “hand preference” just as humans do strikes me as just the most delightful thing.

How Is Climate Change Affecting Walruses?While a little less weird than the handedness fact, this is also really, really interesting. Because it actually depends.

For the North East Greenland walruses, warming climates might be a good thing. That’s because, in the winter, the shallow water where walruses feed is actually frozen right to the ocean floor. This “fast ice” forces the walruses to winter on offshore sea ice, where the ocean bottom can be as much as 200 m down. Longer travel times mean less time to feed at the bottom before running out of air.

Right now, the coastal feeding grounds are available to walruses between the end of July and October, when the water re-freezes. Climate change means that the open-water period is getting longer, and open water seems to be good for food production in the area. So it’s possible that the North East Greenland walruses, a small population that currently numbers about 1000, might actually increase – at least for a while.

It’s a different story for Pacific walruses, like those shown it the picture. Female walruses raise their young near the edge of the summer sea ice, which used to give them a place to rest with good access to shallow water feeding grounds. In recent years, however, there’s been more summer melting, meaning that the ice edge is retreating farther from shore. That puts the mamas over deeper water, making it harder for them to find food for themselves and for making milk for their young. For walruses in this type of habitat, loss of summer sea ice could become a major threat.

If you want to led the walruses a helping hand (I’m sorry, the puns, they write themselves), stay tuned. On May 2 – release day! – I’ll be posting a resource list that includes information on climate change and ways that we can help. In the meantime, keep doing all the things you are already doing to make our world a better place for humans and for polar wildlife.

Polar: Wildlife At the Ends of the Earth comes out in 4 more sleeps! EEK! Pre-order a copy from your local independent bookstore to reduce your carbon footprint AND support a cornerstone of your community.

Don’t forget to check my Public Appearances page for Polar virtual events and live events happening near you! Are you a teacher or librarian? I’m available for author visits in May and June – contact me to secure your spot.

April 27, 2023

Ermines: Serial Killers or Survival Experts?

Predator-prey relationships are a natural part of nature – unfortunate for the prey, but necessary at the scale of ecosystems. As a scientist who studied carnivores, I sometimes forget that I was also a kid who sobbed whenever a fictional fur-bearer died.

Predator-prey relationships are a natural part of nature – unfortunate for the prey, but necessary at the scale of ecosystems. As a scientist who studied carnivores, I sometimes forget that I was also a kid who sobbed whenever a fictional fur-bearer died.

This is why writers need editors – they remind us that not every eight-year-old is emotionally equipped for “nature red in tooth and claw.” And then they make us take that scene out of the book!

So consider this your content warning: today’s post is about murder weasels.

“Murder weasels” is not their real name, of course – in North America, we call them ermines, while in Europe they’re often called stoats. And all members of the weasel family are pretty murdery – wolverines will face down wolf packs to protect a kill, and fishers hunt porcupines by biting their faces until they bleed to death. But not every member of the weasel family does the murder while being. So. Darn. Cute.

I mean, just look at that adorable little serial killer. There is a reason humans keep pet ferrets, after all.

But back to the science…

Just how murdery does an ermine get? Here’s a deleted scene from the first draft of Polar: Wildlife at the Ends of the Earth:

The ermine undulates though the spaces beneath the snow, scenting for lemmings. Even here, beneath a drift 1.4 m deep, cool air sucks the heat from her long, thin body. She needs at least 1/4 of her weight in food each day, just to keep warm and keep going. And she is pregnant. Unless she finds food soon, the babies in her belly will starve before they’re even born.

Here’s another lemming nest, but like the others she’s found this winter, it’s abandoned. All is not lost, though, because the little ermine planned ahead. She bounds back through the tunnels towards last year’s den. In the summer, when the hunting was good, she stashed 153 lemmings in a cavity beneath the rocks. The entrance to her cache is narrow, so foxes couldn’t raid it, and the permafrost kept the meat cool and fresh. The ermine withdraws a morsel from her icebox, curls up in her fur-lined nest, and begins to eat.

153 lemmings killed and stored for later. 153!!!

Dr. Benoît Sittler studies wildlife in Greenland, where ermine are found as far north as 83 degrees latitude. He tells me that ermine caches are hard for scientists to find, but several at least as large as this one have been discovered. Though the scale of the slaughter seems excessive, caching is an essential adaptation. In Greenland – and throughout the Arctic – lemming populations boom to huge numbers before crashing into scarcity. Caching is a predator’s insurance policy – by storing excess prey during booms, they guarantee they’ll have something to eat when live lemmings are scarce on the ground. The adaptation is especially important for small animals – like ermines – that can’t store much body fat against the lean times.

There’s one aspect of the ermine’s behaviour that makes these murder weasels seem particularly ruthless. They run through tunnels under snowbanks, seeking out lemmings that have nested in shelter under the snow. They eat the lemmings, and then nest in the fur they’ve pulled off their victims. Which, on the one hand, yikes. On the other, this is also a highly practical survival strategy. While ermines’ white winter fur provides excellent camouflage against snow, it’s not much warmer than their brown summer coats. Lemming nests – and lemming fur – provide a little extra insulation during frigid polar winters.

What do you think? Are ermines serial killers or survival experts? I’d love to hear from you.

Five more sleeps until Polar: Wildlife at the Ends of the Earth hits bookstore shelves! Pre-order a copy from your local independent bookstore to reduce your carbon footprint AND support a cornerstone of your community. You can also order from your favourite online retailers.

Don’t forget to check my Public Appearances page for Polar virtual events and live events happening near you! Are you a teacher or librarian? I’m available for author visits in May and June – contact me to secure your spot.

April 26, 2023

Ice Worms and Appropriation of Inuit Culture

Six more sleeps until Polar!

Today’s post was going to be about the science of ice worms, a species I wanted to include in the book but ended up cutting because their range (at least in Alaska) is farther south than the Arctic tundra regions that Polar focuses on.

The reason I initially wanted to include them is because, when I was a little girl, my grandparents went to Alaska and brought me back a souvenir: a toy ice worm. It was a strip of white rabbit fur with googly eyes glued to one end, bearing no resemblance to the real species (Mesenchytraeus solifugus, if you want to look them up). But I loved it because I could make it “dance” by stroking a finger down its silky back.

I don’t have the toy any more, so I was googling for photos to illustrate this post and stumbled on references to Inuit folktales about ice worms. I was delighted, because I love folktales from all cultures, and the references were on the websites of universities and museums – places that are normally considered credible.

Not this time.

It turns out that, in Canada, ice worm toys are an example of cultural appropriation… and the “Inuit legend” about them was a marketing tactic written by white people.

The full story appears in a 2019 issue of Tusaayaksat Magazine, which centres on Inuvialuit culture, heritage, and language. The piece is called Sewing Culture, and was written by Charles Arnold. The section on ice worms is at the bottom, but I encourage you to read the entire article.

Polar is about animals, not people. But people have also lived in the Arctic for millennia, and their true stories deserve to be heard.

Polar: Wildlife At the Ends of the Earth comes out in 6 more sleeps! EEK! Pre-order a copy from your local independent bookstore to reduce your carbon footprint AND support a cornerstone of your community.

Don’t forget to check my Public Appearances page for Polar virtual events and live events happening near you. Are you a teacher or librarian? I’m available for author visits in May and June – contact me to secure your spot.

April 25, 2023

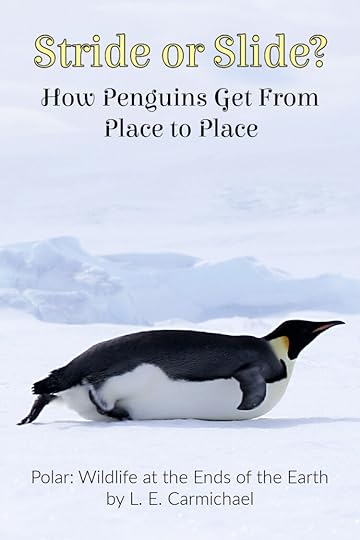

Stride or Slide? How Penguins Get From Place to Place

It’s World Penguin Day! According to Penguins International, there are 18 species of penguins worldwide, three of which appear in Polar: Wildlife at the Ends of the Earth:

It’s World Penguin Day! According to Penguins International, there are 18 species of penguins worldwide, three of which appear in Polar: Wildlife at the Ends of the Earth:

Polar is a book about the adaptations that help penguins (and other animals!) survive in Antarctic habitats. That meant I had to focus on showing the adaptation at work in the wild… which meant that I couldn’t talk about some of the mind-boggling ways that scientists have studied these adaptations.

Until now.

Two of the most eye-popping experiments I came across related to penguin movement patterns. Specifically:

how much energy does a penguin use to walk?how much energy does a penguin use when tobogganing on its belly?how do snow and ice conditions influence which style of movement a penguin chooses?Snow and ice conditions, it turns out, have a big effect on the amount of energy penguins burn just getting around. Adult Adélie penguins weigh about 5 kg. Each foot is about 255 cm square, but their bellies are about 1800 cm square. Dividing weight by area tells us that foot load is around 19.6 g / square cm, but “belly load” is only 2.8 g / square cm.

In other words, if the snow is soft, a walking penguin’s feet will sink in deep, and it will have to expend extra energy pulling its feet out before taking each step. A tobogganing penguin won’t sink as deep, and will use less energy pushing itself forward – especially on a downward slope where gravity lends a flipper!

The amount of friction between the penguin’s belly feathers and the sliding surface also affects the amount of energy it burns while sliding: a slick surface like smooth ice offers less resistance than uneven or coarse surfaces. How did scientists measure that friction? The experiment was more eyebrow-raising than eye-popping. They sedated a penguin, tied a string to its beak, and pulled it forwards. Once they confirmed that a “freshly killed” penguin gave the same results, they dragged a dead bird both forwards and backwards across the snow.

That was in the early 1990s, and – thank goodness! – the ethics governing animal experiments have evolved considerably since then. I can’t imagine scientists getting permission to perform such an experiment today. But those old-school biologists did manage to prove that friction going backwards is much higher than friction going forwards, which means that, when penguins toboggan uphill, their belly feathers act like tiny little crampons, digging into the surface and helping to prevent them from sliding back down to the sea. So that’s something, I guess?

The second experiment I discovered contains much less ickiness. In fact, it’s entirely delightful.

Like a lot of critters that spend most of their time in the water, penguins have a streamlined shape. Their legs are short and set far back under their bodies, which helps reduce drag in the water. When walking, however, those short, rear-positioned legs produce a whole lot of “lateral displacement,” meaning the penguin has to swing its body from side to side just to get its feet going forward. Compared to similar-sized birds with longer legs, this takes a whole lot of energy.

To figure out just how much energy penguins were burning, Dr. Berry Pinshow and his team measured their metabolic rate by measuring how much oxygen their bodies were consuming. To do that, they trained penguins to walk on treadmills while wearing gas masks that captured their breaths.

And we will now pause for a moment to appreciate the sheer awesomeness of that mental image:

PENGUINS. On TREADMILLS. Wearing GAS MASKS.

You’re welcome.

Pinshow’s team determined that top walking speed for an emperor penguin is about 2.8 km per hour, which required an average of 85 steps per minute. In comparison, rheas – birds with the same body mass but longer legs – only had to take 50 strides per minute at that speed. If the math is confusing, remember what it was like when you were a kid, trying to keep up with a parent in the supermarket – you (the penguin) had to take a lot more steps than your grown up (the rhea) to cover the same distance in the same amount of time.

Which means penguins burn more energy walking than birds that have evolved to spend more time on land. No wonder penguins often choose to toboggan – it takes a lot less energy! And if your breeding colony is 300 km from the place where you get your food, every calorie counts.

Teachers! Do you want your students to see pictures of penguins on treadmills? Because I’ve got them, and they are flat-out AMAZEBALLS. Contact me to schedule a school visit.

Seven more sleeps until Polar arrives. Pre-order your copy from your local indie or your favourite online retailer. And don’t forget to check my Public Appearances page for Polar virtual events and live events happening near you!

April 24, 2023

Eleven Reasons Arctic Foxes Are the Coolest

I learned about a LOT of amazing animals while researching Polar: Wildlife at the Ends of the Earth, but arctic foxes will always have a special place in my heart. One reason is that I spent 6 years studying them (and wolves) for my PhD. The other reason is that arctic foxes are COOL. Here’s why.

I learned about a LOT of amazing animals while researching Polar: Wildlife at the Ends of the Earth, but arctic foxes will always have a special place in my heart. One reason is that I spent 6 years studying them (and wolves) for my PhD. The other reason is that arctic foxes are COOL. Here’s why.

1) Look at that little face! This critter knows exactly how cute it is. Notice how its nose and ears are stubby compared to those of other foxes. Those are adaptations that help keep the heat in during a frigid Arctic winter.

2) Arctic foxes have fur on their toe pads (not just in between their toes), which protects them from snow and ice. They are the only member of the canine family with furry feet. They are also the only canine with a seasonal colour change.

3) Foxes sleep in “ball form,” curled up so that only their fuzzy bits are exposed to the elements. In the wild, the temperature difference between the inside of a balled-up fox and the outside air can be up to 52.5 C!

4) In one lab experiment, and arctic fox kept a -80 C for one hour shivered, but maintained its normal body temperature. Do NOT try that at home, kids!

5) Arctic foxes have been known to keep warm by hollowing out reindeer carcasses and crawling inside. Kind of like Luke Skywalker in a Tauntaun.

6) In most parts of the arctic, their primary food is lemmings. Every four years(ish) the lemming population crashes, and foxes have to find other food supplies. In the opening scene of Polar, a fox is following a polar bear’s trail, hoping to steal his leftovers. This is a popular strategy, though not without risk. Hungry bears do occasionally eat the fox…

7) Fox mothers adjust the size of their litters – in the womb – to match available food resources. In a good lemming year, they can have as many as 24 pups.

8) On Mednyi Island, where female pups inherit their mom’s territory and male pups disperse to find their own, fox mothers can adjust the sex ratio of their litters to match food resources. Moms in good territories have more girls, and moms in poor territories have more boys. AMAZING.

9) One of my own studies showed that, in some conditions, fox moms share dens so they have extra adults to care for their pups. One mom can also have a mixed litter of pups with different fathers. This helps increase genetic diversity in the young, a good strategy when environmental conditions are changeable. With luck, at least one of those pups will have the right mix of traits to surviving in its surroundings.

10) In 2019, scientists tracked a fox that traveled 3506 km in 76 days (the previous record was 2300 km in a single winter). That is really impressive when you consider how short their legs are! Polar connection: one of the scientists who made this discovery is Eva Fugeli. Eva and I collaborated on fox research when I was a graduate student, and she was kind enough to provide an expert review for the book.

11) Arctic foxes grow gardens! Like beavers and elephants, they are ecosystem engineers, changing their habitats in ways that affect a lot of other species. Prey carcasses and fox droppings collect around dens, leading to plant growth so lush, scientists can spot dens from the air. The gardens are also prime lemming habitat – in Polar, a litter of baby lemmings snoozes under such a garden.

Do you have a favourite fox? What’s your favourite Arctic animal, and why? Share in the comments!

Eight more sleeps until Polar: Wildlife at the Ends of the Earth hits bookstore shelves! Pre-order a copy from your local independent bookstore to reduce your carbon footprint AND support a cornerstone of your community. You can also order from your favourite online retailers.

Don’t forget to check my Public Appearances page for Polar virtual events and live events happening near you! Are you a teacher or librarian? I’m available for author visits in May and June – contact me to secure your spot.

April 23, 2023

The Work It Takes to Write a Book

Nine more sleeps until it’s pub day for Polar!

Kermit GIF from Kermit GIFsToday is World Book and Copyright Day, so I’ve been reflecting on how much time and work goes into writing just one children’s book.

TimeFour years, people.

In the Polar folder on my hard drive, the “Early Planning” documents are all dated April 2019. That’s when I started mapping out what this book might be. The final manuscript is dated March 2022. It took another year for Byron Eggenschwiler to do his fantastic illustrations and for the book to go through layout, copy editing, printing, and shipping to stores.

WorkFirst, let’s talk research. I set a new record with this one – 339 sources, comprising thousands of pages. Polar is only 48 pages long.

Most of my sources were journal articles describing original scientific research:

Organizing source material: I’m gonna need a bigger office.

(Aside: I used to print journal articles so I could prop them up and read them while simultaneously typing notes into my computer. Now I have two monitors, so I can open the PDF on one screen and open my notes on the other. It’s harder on my eyeballs, but much better for the environment.)

Most of Polar is written in a narrative, storytelling format, but rest assured, it is not fiction. Every single sentence is supported by research. I take my responsibility to my readers very seriously – in my books, kids get the very best information available.

Balancing storytelling with rigorous fact checking is a tricky process. I have no idea how many drafts I did before sending the “first draft” to my editor Katie Scott, but we went through seven drafts together.

CopyrightCopyright is what ensures that I (eventually) get paid for all that time and work. It identifies me as the creator and legal owner of my books. Thanks to a recent update to Canadian copyright law, I will earn about $1 from every copy of Polar sold for as long as the book remains in print – theoretically, up to 70 years after I’m gone.

Thanks to other changes in Canadian copyright law, however, it’s become much easier for people to copy and distribute books without paying for them. According to data collected by The Writers’ Union of Canada, the average writer in Canada now makes about $11,000 a year from their work. And that work includes more than just royalties from book sales – it includes freelance contracts, school visits, teaching jobs, and any number of other writing-related “side hustles.”

I do all of those things, but the main reason I’m privileged enough to work as a full time writer is because I have patrons – people who are willing to support my writing habit purely because they love me personally. Tech Support is chief patron. My Dad and my Not-So-Evil-Stepmother have also been an important source of financial support through the years.

Love Books? Support CopyrightThe pandemic has reminded us of the value of storytelling – be it fiction or nonfiction, book or movie or series, that “content” gave us information, and hope, and a desperately-needed escape from difficult realities. And every piece of content has a person behind it – a person who worked really hard for a very long time to bring something valuable into the world. So this World Book and Copyright Day, buy a book, if you can.

If you can’t, there still are plenty of ways to support your favourite creators:

Talk about their work – write a review, send a tweet, tell a friendAsk your local library to add your favourite authors to the collectionEncourage your kids’ schools to use Canadian books in the curriculaWrite your MP, asking that Canadian copyright law be updated to support Canadian creators

Need more information? Check out the links below. And no matter what else you do today, read a book!

The Writers’ Union of Canada – Copyright Advocacy

Shifting Paradigms: Report of the Standing Committee on Canadian Heritage

Canadian Children’s Book Centre – History Book Bank

Canadian Children’s Book Centre – Social Justice and Diversity Book Bank

Polar: Wildlife At the Ends of the Earth comes out in 9 more sleeps! EEK! Pre-order a copy from your local independent bookstore to reduce your carbon footprint AND support a cornerstone of your community.

Don’t forget to check my Public Appearances page for Polar virtual events and live events happening near you! Are you a teacher or librarian? I’m available for author visits in May and June – contact me to secure your spot.

April 22, 2023

The Earth’s Albedo: What It Is and Why It Matters

Despite the giant window in my office, the room was unbearably dark. Aging eyes feeling the strain, I replaced the light fixture with a brighter one. That helped, sort of. But on cloudy days, it was still a dim and gloomy place to work.

Despite the giant window in my office, the room was unbearably dark. Aging eyes feeling the strain, I replaced the light fixture with a brighter one. That helped, sort of. But on cloudy days, it was still a dim and gloomy place to work.

Last summer, Tech Support and I renovated. The first thing we did was repaint in a lighter colour. Why?

Because of albedo.

What Is Albedo?Albedo is a measure of how much incoming light reflects off a surface. Dark-coloured surfaces, like roads paved with asphalt, have low albedos, meaning they absorb most of the sunlight that hits them… and its heat. If it’s midsummer and you’ve made the mistake of stepping onto the road in your bare feet, you’ve experienced this personally! Likewise, you’ve felt the relative coolness when you hopped back onto the concrete sidewalk. Light-coloured concrete has a high albedo, reflecting most of the sunlight that hits it, and, as a result, staying much cooler.

The same holds true of natural surfaces: rock, soil, and deep dark water have low albedos, while snow and ice have high albedos. Have you ever stepped outside on a sunny day during a Canadian winter? Most likely, your eyelids slammed instantly shut to block out the light bouncing off the snow. That’s albedo at work.

Why Does Albedo Matter?The Earth’s albedo is directly linked to climate… and climate change. We all know that, as global climate has warmed, glaciers and the polar ice caps have begun to melt. What’s not often discussed is that the surfaces revealed by this melting are mountain rocks and deep ocean waters. In other words, surfaces with lower albedos than snow and ice.

As they emerge, these dark surfaces start to absorb energy from the sun, causing them to warm up. That warmth accelerates the melting of nearby snow and ice… revealing more rocks and water. Climate scientists call this self-perpetuating cycle the Ice-Albedo Feedback. It’s one reason that the Arctic and Antarctica are warming up five times faster than anywhere else on Earth.

Putting polar wildlife, and the entire planet, at risk.

Tech Support covers low-albedo lavender with high-albedo pearl pink. It’s SO much brighter in my office now!

What We Can DoClimate change coverage in politics and the news tends to focus on individuals, emphasizing ways we can reduce our personal carbon footprints. To be totally clear, I am 100% in favour of every person on the planet doing our personal bests to protect it. But I – and the scientists that I interviewed while writing Polar: Wildlife at the Ends of the Earth – worry that this emphasis on personal responsibility diverts attention from the much greater harm done by corporate and political policies.

So this Earth Day, as we recycle, plant trees, and walk instead of drive, let’s consider doing one more thing for the planet – speaking up:

attending a climate protestwriting letters to our elected officials, urging them to support environmental and climate initiativesdemanding that corporations adopt climate-friendly policies… and voting with our dollarsdonating to environmental advocacy organizationsHow are you taking action this Earth Day? Share your strategies in the comments.

Polar: Wildlife At the Ends of the Earth comes out in 10 more sleeps! EEK! Pre-order a copy from your local independent bookstore to reduce your carbon footprint AND support a cornerstone of your community.

Don’t forget to check my Public Appearances page for Polar virtual events and live events happening near you! Are you a teacher or librarian? I’m available for author visits in May and June – contact me to secure your spot.

March 31, 2023

Sheryl McFarlane: Celebrating Welcome Rain!

Welcome to Cantastic Authorpalooza, featuring posts by and about great Canadian children’s book creators! Today’s guest:

Sheryl McFarlane

. Take it away, Sheryl!

Welcome to Cantastic Authorpalooza, featuring posts by and about great Canadian children’s book creators! Today’s guest:

Sheryl McFarlane

. Take it away, Sheryl!

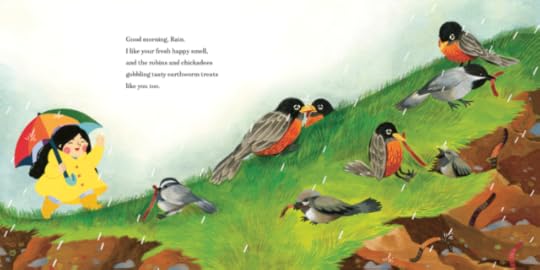

Hi, I’m Sheryl McFarlane and I’m pleased to announce the release of my newest picture book, Welcome Rain! It’s published by Greystone Books, and illustrated by the very talented Christine Wei.

Welcome Rain! is a a celebration of rain in the form of a conversation between a child, and Rain.

It’s about running out to greet rainy days,

but…sometimes wishing rain would take a vacation.

It’s about puddle-jumping, and the wonder of raindrops sparkling on spider webs. It’s about appreciating how rain helps our gardens grow.

It’s about knowing that rain quenches thirsty streams and forests, and the plants and animals who live in and near them. Welcome Rain! encourages outdoor play, even on rainy days.

As a former teacher, I loved using picture books to introduce a theme or concept. Here are some fun ways for primary and preschool teachers to extend learning after reading Welcome Rain! to their classes.

Puddle Jumping Math is sure to make a splash!After a heavy rain, take your class out to do a little puddle jumping. Bring along some extendable tape measures. Kids love to measure stuff! Have students take turns jumping in puddles to see who can splash the farthest. After measuring each participant’s splash, head back inside to create a large bar chart which can be taped up so students can see how far they jumped. (If some students don’t have rain gear, they can help with the measuring.)

Create a Rainstorm or Rain Choir (kids love this group activity) The leader starts by rubbing their hands together. A second person joins in, and then another and another until everyone is making the same sound together.The leader gently starts to clap their hands while the rest of the group continue to rub their hands together.The next person joins hand clapping, and so on until everyone is clapping.The leader slaps their thighs while the others continue to clap hands.The second person slaps their thighs and so on until everyone has joined in.The leader starts to stomp their feet.The next person joins in and so on until everyone is making the same sound.To end the storm, reverse the actions until the leader is the last one to rub their hands together and then stop.Rainstorming is a cool language arts activity

A second person joins in, and then another and another until everyone is making the same sound together.The leader gently starts to clap their hands while the rest of the group continue to rub their hands together.The next person joins hand clapping, and so on until everyone is clapping.The leader slaps their thighs while the others continue to clap hands.The second person slaps their thighs and so on until everyone has joined in.The leader starts to stomp their feet.The next person joins in and so on until everyone is making the same sound.To end the storm, reverse the actions until the leader is the last one to rub their hands together and then stop.Rainstorming is a cool language arts activityUse chart paper and felts to brainstorm different words and phrases we use to describe rain. Then have students make up a story using some of these words or phrases. Here’s a few hints…

downpourraining bucketsRain in a jar is an easy way to show kids how the water cycle worksYou’ll need:

a medium sized glass jar (canning jar)a platehot waterice ice cubesInstructions:

An adult pours about two inches of very hot water into the glass jar.Cover the jar with the plate and wait a few minutes before you start the next step.Put the ice cubes on the plate.Observe what happens…How this works:

The ice-cooled plate causes moisture in the warm air inside the jar to condense and form water droplets. This is the same thing that happens in our atmosphere. Warm, moist air rises and meets colder air high in the atmosphere. The water vapour condenses and forms water droplets (rain) to fall.

Get in Touch! I’d love to hear what activities Welcome Rain! inspires for you! Welcome Rain! Is available through your favourite Indie bookstore, via Amazon, Chapters/Indigo, Barnes and Noble, and Target.

I’d love to hear what activities Welcome Rain! inspires for you! Welcome Rain! Is available through your favourite Indie bookstore, via Amazon, Chapters/Indigo, Barnes and Noble, and Target.

Sheryl is the author of seventeen books for kids. She lives in Victoria, BC where she enjoys splashing in puddles with her grandchildren, and the rainy days she does not have to water her garden. Visit her at www.sherylmcfarlane.ca

March 20, 2023

Here Comes the Sun: Spring Equinox and Circadian Rhythm

Last weekend, many of us suffered through the tortuous ritual known as “springing ahead” – moving the clocks forward one hour to begin Daylight Savings Time.

Last weekend, many of us suffered through the tortuous ritual known as “springing ahead” – moving the clocks forward one hour to begin Daylight Savings Time.

We hates it, precious.

I live in the Northern Hemisphere, and I am very, very sensitive to ambient light levels. I hate getting up in winter darkness even more than I hate winter temperatures – and I’m medically allergic to cold. So when the days start to get longer and it’s actually – gasp! – sort of light out at 6:30 AM, my brain throws a party.

Then Daylight Savings Time begins, and my brain wants to throw rocks at whoever invented it.

And yes, I have a wake-up light next to my bed and a light therapy lamp on my desk. But glancing out the window undermines any effort I make to convince myself that being awake is a good idea.

I’m not alone in this. Humans and many other creatures have what are called circadian rhythms – internal clocks that tell us when to wake up and when to sleep. There are complex genetic cascades involved in control of these rhythms, but those controls are calibrated by signals from the environment – namely, light. The blue light receptors in our eyeballs communicate with our brains, triggering changes in the levels of melatonin in our blood. That’s why sleep experts recommend reducing artificial light levels before bed. And it’s why so many people take melatonin tablets to combat jet lag – air travel confuses our internal clocks.

But in some ways, we humans are lucky – we can manage our internal clocks (and cope with Daylight Savings Time) by artificially manipulating our light exposure. Animals don’t have that option.

Here Comes the SunPolar animals face an additional challenge – the most radical changes in day length anywhere on the planet! In fact, light regime is the thing that makes the Arctic and Antarctica truly unique. There are other habitats on Earth that get just as cold, or just as dry, or just as windy. But there are no other places where (depending on latitude), day – and night – last up to six whole months.

There hasn’t been much research on circadian rhythm of polar animals, mostly because the research is really hard to do. Lab experiments with Antarctic krill can’t fully replicate what’s going on in the wild, and trying measure changing hormone levels in large animals like caribou would be pretty stressful for both animals and humans. What scientists have discovered is that – no surprise! – polar animals have rhythms that are flexible and responsive to changing conditions. That allows them to adjust their behaviours – like feeding, resting, or migrating – to maximize survival in challenging habitats.

Today’s the March Equinox – in the Northern Hemisphere, it’s now officially spring. Between DST-induced darkness and the two feet of snow on the ground, it really doesn’t feel like spring where I live. And I confess that, despite extensive research while working on Polar, I still don’t fully grasp the concept of “equinox” from an astronomical standpoint. There’s a reason I write about Earth and not space!

But here’s what I do know – at the North Pole, the sun came up today, for the first time since September. And that feels like something to celebrate.

To Learn MoreCircadian rhythm is one adaptation featured in my upcoming book, Polar: Wildlife at the Ends of the Earth. It’s available to pre-order now.

Are you a teacher or librarian? Contact me to schedule a Polar presentation in May or June!

March 13, 2023

Award-winning Author Pens New Science Book for Kids on Polar Wildlife

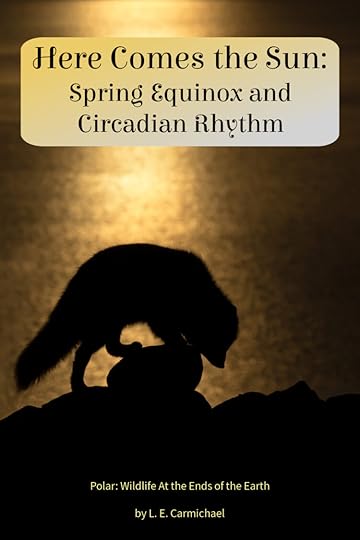

Despite changing climate and savage conditions, animals in the polar regions can still thrive. Author L. E. Carmichael’s 23rd children’s science book takes a fascinating look at how they manage it—and how young environmentalists can help.

Despite changing climate and savage conditions, animals in the polar regions can still thrive. Author L. E. Carmichael’s 23rd children’s science book takes a fascinating look at how they manage it—and how young environmentalists can help.

Polar: Wildlife at the Ends of the Earth is Carmichael’s 23rd children’s science book. Carmichael’s 2020 release, The Boreal Forest, appears on “Best of” lists in both Canada and the US; it won the Information Book Award and received an honour in the Forest of Reading, Canada’s largest children’s choice awards program.

Fuzzy Forensics, based on Carmichael’s first-hand experience fighting crimes against wildlife, won the 2014 Lane Anderson Award for best Canadian children’s science book.

Carmichael said she writes to fire children’s imaginations and spark their curiosity.

“So many people have the idea that science is a collection of facts they have to memorize,” Carmichael said. “My mission is to help kids discover what science is really about—asking questions, paying attention, and staying alert to the wonders of the natural world.”

Wonders certainly abound in Polar, which features both iconic animals—like polar bears and penguins—and weirder species, like woolly bear caterpillars and glow-in-the-dark lantern sharks.

“One of my favourite critters uses projectile vomit to protect itself from predators,” Carmichael said. “My inner kid thinks that’s hilarious, and I suspect actual kids will, too.”

Newly released from Kids Can Press, Polar draws on meticulous research and first-hand experience. Carmichael attended junior high while living in Yellowknife, and has vivid memories of polar night and the midnight sun.

“My teenage brain did not like either one, but the land and its creatures got into my blood,” she said.

That’s one reason the University of Alberta alumna chose to study northern wolves and arctic foxes for her PhD in wildlife genetics. Her dissertation won the Governor General’s Academic Medal.

Polar shows how Arctic and Antarctic species have adapted to the challenges posed by their habitats, including bitter cold, ferocious winds, and darkness lasting up to six months. But the adaptations which currently help them might harm them as their habitats continue to change.

“Climate change is a real and pressing danger for many of these species, but there is still so much we can do to protect them,” Carmichael said.

Her book includes ways that junior environmental activists can take action.

“I want my readers to feel amazed, but also empowered to make a difference,” she said.

With stunning art by award-winning illustrator Byron Eggenschwiler, Polar debuts on May 2, 2023. Carmichael, who lives in Trenton, has planned several in-person and virtual events to celebrate the launch.

Visit her website at www.lecarmichael.com for a full schedule, plus free educational resources for parents and teachers.