Lee Kelly's Blog, page 2

October 11, 2023

With Regrets Book Tour

With Regrets is going on tour! I’ve got several events this fall, in person and virtual, and hope you can join the fun!

Things kicked off on Thursday September 7th at my local wonderful bookshop The BookHouse in Millburn, where I had the chance to speak with Liz Alterman, author of The Perfect Neighborhood. I’m speaking with Alan Warren of the House of Mystery Radio on September 13th (the show will be available on podcast if you can’t catch it live!) in addition to visiting a few more fabulous in...

BookBub Loves The Antiquity Affair

Jenn and I were so thrilled to see The Antiquity Affair featured on BookBub's roundups for best new historical mysteries; mysteries featuring female sleuths; and new books about archaeology.

If you're NOT a member of BookBub, I highly recommend the site as a way to connect with other readers and discover new books. Check it out!

...Recap: The Antiquity Affair Book Tour!

What happens when you let loose two authors on a six state, six day book tour extravaganza?!

Click to see our shenanigans, and cheers to misadventure!!

Video compilation of The Antiquity Affair book tour with co-authors Lee Kelly and Jennifer Thorne

More about The Antiquity Affair

May 19, 2023

The Antiquity Affair – East Coast Book Tour!

THE ANTIQUITY AFFAIR is going on tour! Lee Kelly and co-writer Jennifer Thorne are hitting the road to celebrate their release! Six book launch events in six days – come join the fun!

Tuesday June 6 - Astoria Bookshop | 7PM

Queens, NYC

Wednesday June 7 - Booked at Island Creek Oyster Bar | 5:30PM

In conversation with Lori Goldstein

Duxberry, MA

Thursday June 8 - Private event with Jenni Walsh, with sales by The Book House, Millburn, NJ

Friday June 9 - Perry Library | 6PM

In co...

February 13, 2023

With Regrets – New Thriller Novel from Lee Kelly Just Announced!

From the author:

I’ve been waiting to share the exciting news: I’ve got another novel coming this fall, my “Real Housewives of the Apocalypse” thriller!! So grateful to my agent @katelyndetweiler and to be working with @toni_m_plummer and the wonderful Alcove team!!

View this post on InstagramPREORDER THE BOOK ABOUT WITH REGRETSA post shared by Lee Kelly (@leeykelly)

With Regrets, from author Lee Kelly, is equal parts Big Little Lies and Bird Box, a subur...

Graduated my Masters Program at VCFA!

This past weekend I graduated from my masters program at Vermont College of Fine Arts – with an MFA in Writing for Children and Young Adults. It’s been an incredible four years: I’ve made truly amazing, lifelong friends, gotten to try all sorts of different writing genres I never have before, and capped the experience off with giving a lecture on a subject near and dear to my heart, as well as walking in person after so many semesters online. Three cheers to all the Allusionists who recently gr...

December 6, 2022

World Building in “What-If” Short Stories: Tips and Tricks

After a few months of perusing short fiction, I’ve noticed some emerging reader preferences: many of my favorite stories have been those that propose a speculative twist on our world, present a character “native” to this world, and then spin this character’s personal struggle against its “what-if” landscape to glorious effect. These stories’ authors manage to present fully lived-in worlds while still delivering satisfying narratives and character complexity: how do they do it all in the span of several thousand words?

There’s lots of advice on world building in craft guides and articles, most of which stresses that a story’s world must always serve the story’s narrative, and that such service should feel organic. As Ursula Le Guin explains, speculative writers must strive to avoid “info dumping” world-building exposition and instead, impart details strategically and selectively, so that they read like “functional, forward-moving element[s] of the story” (Le Guin).

This advice makes sense in theory, but what does application of these principles look like in practice? If one were to examine a handful of stories from a certain ilk, would there be similar patterns or authorial choices?

To determine, I analyzed two short stories categorically similar to my own creative work – “Each to Each” by Seanan McGuire and “Anxiety is the Dizziness of Freedom” by Ted Chiang – to see if there were any similarities or takeaways. Like my own story for this packet, both of these stories are 1) set in a speculative “what-if” world; 2) have a “native” as its central protagonist; and 3) are longer than the traditional short story (5,000-plus words).

As a threshold matter, both McGuire’s and Chiang’s speculative pieces begin with a short in media res scene, a snippet of the protagonist in motion that only hints that the story’s world is different than our own. For example, McGuire’s “Each to Each” – a story about female naval officers genetically re-engineered as mermaids – begins with the protagonist walking through her submarine, responding to an “all-hands call” from her captain (McGuire 6). McGuire does not include any straight exposition in this opening scene – indeed, there’s no mention of “mermaids.” Instead, our protagonist complains about her “uncomfortable boots” (McGuire 6); reflects on her crew, who has “signed away” their voices “for a new means of dancing” (7); and studies her colleague who struggles with her “breathing apparatus that fits a little less well after every tour” (7). McGuire’s opening scene is fast, lean, and intriguing, with just enough teasing details to throw us off-kilter and whet our interest in learning more.

Ted Chiang’s “Anxiety is the Dizziness of Freedom” begins with a similar scene: his story opens with protagonist and shopkeeper Nat greeting a customer who is anxious to sell her a “prism” (Chiang 270). Chiang doesn’t tell us what prisms are in this opening; instead, he shows us Nat turning the prism on to see her “paraself” (Chiang 271); quoting the customer a price; and discussing how the prism might be more valuable if it was older or if its “other branch has something really interesting going on” (271). Chiang, like McGuire, keeps his initial scene free of exposition, instead allowing story momentum and in res action to intrigue us into reading more.

After these dynamic opening scenes, however, both stories “pause” to offer a more expositional interlude that details their story’s strange new world – a short “reader orientation” before moving forward. In “Each to Each,” for example, McGuire’s protagonist detours from narrating real-time action to explain her naval mission: via this interlude, readers learn that the Navy is comprised of all women, that these female soldiers have been bio-engineered into “mermaids,” and that submarine teams now comb the seas for potential real estate (given that climate catastrophes have ravaged the surface) (McGuire 7-8). Rather than feeling like an info dump, however, the short detour feels like an exhale after the dynamism of the previous scene, and grounds readers before the action again whisks us forward.

Chiang too employs a pause after his initial scene in “Anxiety is the Dizziness of Freedom,” an interlude which similarly serves as a little primer on his world. We learn how prisms are activated, how they create parallel “branches” of reality, and how people use them to communicate with their parallel selves (Chiang 273-75). Chiang’s detour, while lengthier than McGuire’s, is fascinating and immersive, and also provides important details about the story’s world to frame and inform its subsequent action.

After these “intermissions,” both McGuire and Chiang return to in res storytelling. In fact, in “Each to Each,” nearly all of the remaining scenes are real-time depictions – readers follow McGuire’s protagonist on her exploratory dive with her team; in her conversations with her captain about unidentified sightings in the water; in her return to the open seas where she is confronted by a “rogue” mermaid and offered the possibility of freedom. In each scene, though, McGuire embellishes her story’s action with a myriad of world-building flourishes, all of which enhance the story’s beats and add narrative dimension. For example, when McGuire introduces the naval crew members, she describes each of them in terms of their phase of mermaid transitioning (e.g., “One of the Seamen raises her hand. She’s new to the ship; her boots still fit, her throat still works” (McGuire 9)). Similarly, during the deep-sea dive, the protagonist compares her crew to other countries’ mermaid prototypes: “The American mods focus too much on form and not enough on functionality. Our lionfish, eels, even our jellies still look like women before they look like marine creatures” (McGuire 13). McGuire’s strategically-woven details create a lush, lived-in feeling – a world that complements versus compromises her story’s forward momentum.

Ted Chiang, by contrast, continues to intersplice his real-time action with narrative “pauses,” the entire story oscillating between engaging, in res scenes and world-building asides that explore Chiang’s story construct from different technical and philosophical angles. Do we need all these detours to enjoy Chiang’s actual story? Perhaps not, but they make the reading experience a lot more fun: Chiang’s genius lies in his unique ability to sell the “impossible” as scientifically probable, and at a certain point, his meticulous details somehow transform the story and make it read “real.” Chiang’s numerous intermissions also allow his in res scenes to remain fast-moving and lean, since readers learn his world’s necessary information via these interludes. In any case, like McGuire’s, Chiang’s world still serves his story – just with a different recipe and to a different effect.

My analysis of these stories’ worlds, and their authors’ storytelling choices, was quite illuminating. The study gave me concrete takeaways and ideas that informed my own short story, as well as other potential projects in the hopper.

Chiang, Ted. “Anxiety is the Dizziness of Freedom.” Exhalation : Stories. 1st ed., Vintage, 2019.

Le Guin, Ursula. “Navigating the Ocean of Story: Session 1, Continued.” Book View Café, 24

Aug. 2015, https://bookviewcafe.com/blog/2015/08/24/navigating-the-ocean-of-story-session-1-continued/.

McGuire, Seanan. “Each to Each.” Women Destroy Science Fiction! Special Issue, edited by Christie Yant, Lightspeed Magazine, 2014, pp. 6-22.

Making a Character Come Alive (in 10 pages or less!)

Bringing a character to life in any work of fiction is a difficult task, but the charge is even more challenging in short fiction, where the author has far fewer scenes and pages through which to make their characters feel alive. Fortunately, Janet Burroway offers concrete techniques for achieving this character three-dimensionality in her craft book, Writing Fiction: A Guide to Narrative Craft. In this post, I’d like to analyze a particular short story, Kelly Link’s “The New Boyfriend,” and Link’s characterization of this story’s protagonist, through the lens of Burroway’s devices for achieving effective characterization. I will examine Link’s employment of these characterization techniques – i.e., using scene settings, specific objects, interiority, and secondary characters’ reactions – in turn.

Link’s “The New Boyfriend” tells the story of Immy, a teenaged girl who lives in the perpetual shadow of her best friend, Ainslie. This story opens in media res at Ainslie’s birthday party, where Ainslie is opening her mother’s gift – an expensive, animatronic, interactive “Ghost Boyfriend” that Immy herself has long been coveting. Immy grows increasingly envious of Ainslie’s brooding new Boyfriend; when Ainslie and her mother leave town for spring break, Immy hatches a series of dangerous (and often illegal) schemes to program Ainslie’s Boyfriend into falling in love with Immy instead.

As Burroway tells readers in Writing Fiction, a story’s settings should work to illuminate character (105); in fact, “disharmony” between a story’s setting and a character’s state of mind immediately generates evocative narrative content (106). Link uses such charged, inciting settings for her scenes in “The New Boyfriend.” Consider the story’s opening scene:

Ainslie doesn’t rip open presents. She’s always been careful with her things, even the things that don’t matter. Immy is a ripper but this is not Immy’s present, not Immy’s birthday. Sometimes she thinks that this may not be Immy’s life. Better luck next time around, Immy, she tells herself.” (Link 215)

Link’s choice of setting – Ainslie’s home, on Ainslie’s birthday – immediately frames protagonist Immy as a satellite player, a supporting actress in her own story. In fact, the first fifteen pages of this story revolve around Ainslie: Ainslie’s birthday gift and party, Ainslie’s feelings and desires. Link also sets most of this story’s subsequent scenes in Ainslie’s home or on her property (e.g., Immy sleeping over in Ainslie’s room; Immy breaking into Ainslie’s home to steal the Ghost Boyfriend; Immy clandestinely meeting the Boyfriend in Ainslie’s mother’s storage unit). Even the story’s quieter, more contemplative scenes, such as Immy’s conversation with her father about friendship, take place during commutes to and from Ainslie’s house. Link’s “Ainslie-centric” setting choices brilliantly prod and perpetuate Immy’s frustrations with her shadow status, and further underscore her feelings of inadequacy and disassociation.

Burroway also suggests that writers can deepen their protagonist’s characterization via the use of specific details and objects that prompt emotional, highly-charged character reactions; in Burroway’s words, emotion is “a sensory response within the body to sensory input from the outside world” (Burroway 33). Link uses this technique to stunning extent in “The New Boyfriend;” specific objects serve as “objective correlatives” which showcase Immy’s internal landscape and its evolution throughout the course of the story. For example, consider the homemade absinthe that Immy and the girls drink at Ainslie’s party. At first, Immy regards this homemade brew as just one more emblem of her and her friends’ inauthenticity: they all drink straight from the bottle because “it’s harder for everyone else to tell if you’re only taking little sips or even only pretending” (Link 219). Later on, however, the absinthe becomes a convenient cover for Immy, an excuse to escape her friends and spend some time with Ainslie’s Boyfriend alone (224). When the party winds down, the absinthe bottle becomes symbolic of Immy’s bitterness and jealousy (as Link tells us, at the end of the night, “there’s only a sludgy oily residue left in the absinthe bottle” (227)). Link thus puts her story props to work: objects like the absinthe draw out Immy’s emotional status, and give us unique and pointed windows into Immy’s character.

Per Burroway, “the territory of a character’s mind,” or the direct access to a character’s thoughts and feelings, is also an integral piece of effective characterization (Burroway 70). At first blush, this advice struck me as somehow contrary to the oft-cited writing adage, “show don’t tell,” but sometimes economical “telling” communicates so much more than a myriad of little details ever could. The trick, perhaps, turns on crafting razor-sharp flashes of character insight, versus offering a barrage of diluted and out-of-focus thoughts. Let’s consider Link’s story as an exemplar once more. Near the story’s start, Link tells us that “Immy’s heart isn’t as big as Ainslie’s heart. Immy loves Ainslie best. She also hates her best. She’s had a lot of practice at both” (Link 216). Yes, this passage qualifies as direct telling, but this handful of sentences gives us an effective abridgment of the girls’ entire relationship. Link offers a similar summation of Immy’s relationship with another secondary character, Elin: “she knows what kind of friends she is with Elin. Sometimes a friendship is more like a war” (221). This loaded, insightful line does more with its telling than one hundred “shown” details or explicit moments ever could.

Finally, Burroway offers an indirect method of deepening characterization: the presentation of the protagonist “through the opinions of other characters” (Burroway 77). Such presentation can be accomplished through a secondary character’s actions or dialogue, and can provide readers with a more nuanced, holistic portrait of a story’s protagonist. Link also employs this technique in “The New Boyfriend;” while Immy may frame herself as a jealous, fake, “horrible friend” (Link 220), Link employs shorter, more introspective scenes to demonstrate Immy’s complexity. In a scene late in the story, Ainslie asks Immy to help dye her hair red, only for Ainslie’s overstepping mother to follow suit and do the same. Immy is the person who Ainslie turns to for solace, the one who “cut[s] all the red right out with a pair of scissors” (Link 247). Link also tempers Immy’s insatiable jealousy through other characters’ commentary; on page 226, for example, Elin empathizes with Immy, “I know how much you want [a Boyfriend]. And I know it sucks. How Ainslie gets everything she wants.” These interactions offer additional depth to Immy and soften the edges of her more toxic emotions, rounding her character and adding further nuance.

Link’s employment of these various characterization devices in “The New Boyfriend” bring her protagonist Immy to stunning life on the page. I will continue to refer back to Link’s story as inspiration, and to Burroway’s excellent craft book for guidance, as I attempt to deepen and enrich my own characters.

Burroway, Janet. Writing Fiction, Tenth Edition: A Guide to Narrative Craft. University of Chicago Press, 2019.

Link, Kelly. “The New Boyfriend.” Get in Trouble. Edinburgh : Canongate, 2016.

Reimagining Revision: Some New Ideas for Rebooting Your Stories

Revision is a crucial step of the storytelling process, although the type of creativity we employ during this stage feels different than the energy that fuels freewriting or drafting. In his craft guide, Wonderbook, Jeff VanderMeer even suggests that revision is governed by a separate area of the brain: a “technical imagination” that is capable of seeing a story as a whole, analyzing its structure, and making “the elements of narrative work together in synergistic ways” (VanderMeer 69). It follows, then, that revision should be treated differently than drafting – that revision isn’t simply a continuation of a first draft, but a process wholly apart, an analytic evaluation that dissects and considers the story from a top-down perspective.

This type of approach makes sense in theory, but it’s intimidating, and also a far cry from the revision methodology that I typically tend to employ. My usual process, especially for shorter pieces, involves printing out the story in question, reading through and make some illegible margin notes (e.g., “cut”; “tighter”; “doesn’t make sense”) and then turning back to the computer to begin addressing these vague margin notes in linear fashion.

Perhaps my “rush” to start chipping away at the story, line by line, is driven by an anxiousness to get started, or a desire to be “efficient.” Or perhaps, it’s lazy resistance to structuring a more well-thought-out plan. In any event, it felt time to reimagine my process for short story revisions. So for my speculative story, “Rare Creatures” (now featured in Orca Literary Magazine), I studied and employed several unique approaches, using Jeff VanderMeer’s Wonderbook and Lynda Barry’s What It Is as my guides. My main takeaways from my study are outlined below.

Both Jeff VanderMeer and Lynda Barry strongly believe in the power of handwriting as a tool for unlocking imagination and re-envisioning a work of fiction. Indeed, in Wonderbook, VanderMeer stresses that “[r]evision is work that should not be done on a computer” (VanderMeer 267). Barry, too, suggests that handwriting releases new creativity: that the act invokes a “state of mind which is not accessible by thinking” (Barry 106).

I’m always trying to “write efficiently” with my limited writing time, hence in part why I turn to the computer and often shy away from side-writing exercises. But as Barry asks, what would happen if I stopped thinking of every creative endeavor as “work?” What if I introduced more play into my revision process, understanding that some of my writing will never actually “live” inside the story?

In order to tee up this state of play, I committed to doing my revision work primarily by hand.

Step Two: Handwritten Story DiagnosticVanderMeer recommends printing out a story draft and outlining it in reverse, what he calls “stress testing your story’s structure” in order to see the story’s true narrative shape (VanderMeer 260). Per VanderMeer, this process allows writers to analyze each story scene – noting the scene’s action, information conveyed, causes and effects, and consequences – and flagging those that are stagnant or illogical, or places where the story is too bloated or lean.

I employed VanderMeer’s diagnostic methodology and found the results fascinating: after mapping my story onto “scene” flashcards, it was easy to spot which scenes were slow, and which of the more dynamic scenes needed extra page space. This “reverse outline” also gave me a firmer grasp of my story as it was written (versus how I thought of it in the abstract), and where I could condense or expand various parts of the narrative to add depth and interest.

Step Three: Character AnalysisVanderMeer also suggests that writers run a diagnostic of their characters via a circular diagram, mapping their characters’ relationships, and how these relations can be further strengthened, complicated or made more interesting. He also advises writers to reflect on their characters’ hidden pasts in order to add “depth, layering and connectivity” to the story (VanderMeer 261). This advice reminded me of your voice note in our recent packet correspondence, when you suggested that every secondary character have a secret in order to infuse the narrative with more nuance and mystery (McOmber voice note).

Barry, too, has interesting advice for how to reimagine a story’s characters. If a writer is struggling to find their story’s emotional engine, Barry suggests that they draw inspiration from the age-old notion of “monsters.” She says that every child has a “certain something that really scared us, and seemed to have it in for us. A ‘something’ we had to defend ourselves against in secret ways” (Barry 64). This “personalized monster,” Barry says, is usually informed by people or things in our lives that terrify us (e.g., for Barry, the Gorgon monster recalled her abusive mother). Barry’s reflections got me thinking: could my character’s deep wound ultimately stem from a “monster?” Could I tap into my own fears on the page and breathe new life and personal meaning into my character? At the very least, could I free-write about my protagonist Calla’s fears and dreams, to ensure that her desires are driving engines of the story?

For this revision, I tried both VanderMeer and Barry’s suggestions. VanderMeer’s “character wheel” was such a fresh way to jumpstart brainstorming the relationships and secrets of the characters, and helped me cook up additional ways to entangle the characters. I also used Barry’s “monster” prompts to brainstorm possible needs and wants for Calla, and Barry’s related side-writing exercises triggered some character insights.

Step Four: Allow Space for ReimaginingLynda Barry has always placed a premium on “getting lost” in her creative work: instead of worrying about whether something is “good” or marketable, Barry says, a true artist must be willing to play (Barry 49). While many of her related exercises are aimed at the creation and drafting stages, I found them helpful and applicable to the revision process as well.

Barry is a huge believer in the power of images, and frames an artist’s ability to “unearth” images as a skill that can be practiced, sharpened and perfected with time and dedication. She urges writers to brainstorm ten images from their past, or to lift ten images or nouns from their story; she then instructs her students to choose one of these images, consider prompting questions (e.g., who, what, when, where, why), set a timer for eight minutes and then write about the image without stopping (Barry 148-156). I lifted ten nouns unique to “Rare Creatures” (e.g., ice-bark forests, Wings, barn), and free-wrote about them using Barry’s prompts. I had a ton of fun and moreover, several of these free-writing sessions led to interesting breakthroughs.

Step Five: Written Action PlanI’m a big “list-maker” in my personal life (to-do lists, calendars, notebooks full of goals). But for some reason, I tend to resist “quantifying” or memorializing the scope of revision that I need to do for a story (most likely because I’ll find the list overwhelming). After re-reading VanderMeer’s Wonderbook, however, I realized that an action plan is more of a map than a to-do list – a guide that empowers, instead of overwhelms. So after completing the steps above, I reviewed them all looking for takeaways, action items, and how to group them into “revision passes” (e.g., a pass for building Calla’s internal desires and fears; a pass for adding some nuanced worldbuilding gleaned from Barry’s exercises; a pass for more firmly connecting the characters, etc.).

This “top-down” mapping felt like an insurance plan: proof that I had a handle on what my story needed. I liked this process so much, I’m hoping to bring what I learned and gleaned to all short story revisions going forward.

Barry, Lynda. What It Is : Dramatically Illustrated with More Than Color Pictures. Drawn & Quarterly, 2017.

VanderMeer, Jeff. Wonderbook : An Illustrated Guide to Creating Imaginative Fiction. Abrams Image, 2013.

My 5 Favorite “What-If” Worlds That Feature Sisters

Originally published on Shepherd.com

I’m an avid reader of speculative fiction: fantasy, science fiction, horror, “what-if” stories of our world with a twist... you name it, I’m in. But what really sells a spec-fic story for me is the characters that populate the world – the relationships that form the heart of the otherworldly story – and I’ve always found sisterhood, in particular, extremely compelling. I’ve actually written two speculative books featuring sisters myself, and have another sisters-driven adventure coming out next year! I’m also one of three sisters, and growing up, these relationships served as the basis of so many memories, as well as informed so much of who I am.

The books I picked & why Caraval

CaravalBy Stephanie Garber

Why this book?

I absolutely devoured this lush, evocative fantasy, which tells the story of two sisters who live in a world where a select few are invited to play an immersive, magical game on a remote island. As a writer, I found Garber’s prose to be exquisite; her fantasy world, too – and all of its secrets, spells, and wonders – was crafted meticulously and painted in sumptuous detail. But as a reader, the real driver of Caraval for me was the bond between the main character Scarlett and her sister Tella – such an unforgettable adventure with two unique heroines at its core.

We Have Always Lived in the Castle

We Have Always Lived in the CastleBy Shirley Jackson, Thomas Ott (illustrator)

Why this book?

One of my favorite classics, We Have Always Lived in the Castle defies tidy genre classification. Part mystery, part coming-of-age story (with a bit of Gothic horror too), this wonderful and twisted novel from Shirley Jackson tells the story of unusual Merricat Blackwood and her older sister, the agoraphobic Constance, who live with their uncle in isolation at Blackwood House. I remember frantically turning the pages the first time I read Jackson’s story, which is such a fantastic craft study in expert pacing and psychological suspense. But there’s a beating heart to this story, too, which is what really hooks and invests me—and the singular, fierce bond between Merricat and Constance emotionally anchors Jackson’s gripping tale.

Roses and Rot

Roses and RotBy Kat Howard

Why this book?

Kat Howard’s novel threads so many things that I love together – sisters, reflections on making art and on the artist’s “muse,” faeries, and magical night markets. This story, a loose reimagining of Tam Lin, is set at an artists’ colony, where every seven years, the Fae living at the border of our world select the most promising artist to live among them and, in exchange, grant the artist unparalleled success when they return. But what really gripped me is how differently the two sisters of Roses and Rot consider the Fae, as well as what they’re each willing to sacrifice for fame and fortune, and these disparate attitudes result in such a riveting conclusion. If you’re like me and have a particular fascination with the artistic process and the writer’s life, this novel is not to be missed.

Down Among the Sticks and Bones

Down Among the Sticks and BonesBy Seanan McGuire

Why this book?

This slim novel is actually the second in McGuire’s Wayward Children series, which I wholeheartedly recommend in its entirety. The premise: a school for teenagers who once found secret, magical doors to other worlds when they were younger—and who, for various reasons, are sent back from those worlds to ours again. I particularly loved Jack, the burgeoning mad scientist sister in Down Among the Sticks and Bones, as well as her complicated relationship with her sister, Jill. I’m also a big fan of unique worlds and high-concept premises, and McGuire’s series absolutely checks both of those boxes!

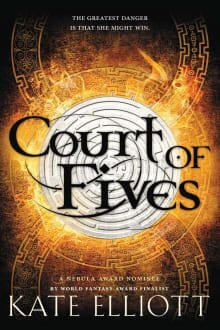

Court of Fives

Court of FivesBy Kate Elliott

Why this book?

Kate Elliott’s young adult series feels a bit like Game of Thrones meets Little Women (both of which I loved, so Elliott’s concept was a dream mash-up for me!). The protagonist, Jessamy, lives in a fantasy world divided by class, a domain where laudable competitors compete in a series of various trials and tribulations called the Fives. As a writer, I found Elliott’s world so well thought out and executed, but it was the Little Women elements of this series that most claimed my reader heart. I treasured the quieter moments between Jessamy and her sisters, who are all memorable, fully rendered, and compelling, and the relationships between them, complex and real.