Elizabeth Graver's Blog, page 3

April 5, 2023

Book Tour Schedule!

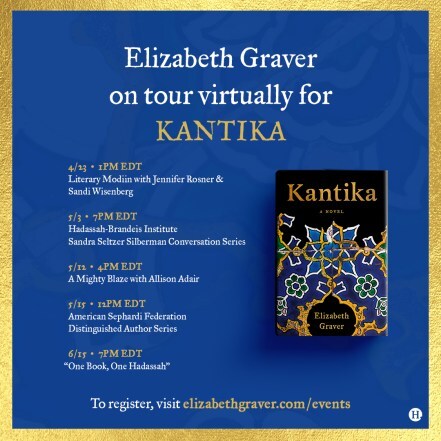

Kantika comes out on April 18th! I’ll have my launch reading at the wonderful Newtonville Books and do other events throughout New England, as well as online. I’m so looking forward to getting to be in conversation with other writers whose work I love, including Tova Mirvis, Aaron Hamburger (whose new novel, Hotel Cuba, is fabulous), Anna Solomon and Judy Bolton-Fasman. My Wesleyan RJ Julia event will be moderated by my wonderful 20-year-old daughter (& Wes sophomore), Sylvie. In Great Barrington, I’ll be in conversation with Sarah Aroeste, whose performances of Ladino songs and Ladino children’s books are an inspiration. In Williamstown, where I grew up, my childhood pal Peter is putting together a wine-tasting and reading at his gorgeous new store, Provisions Williamstown, and in Astoria, Queens, I’ll be reading just a few blocks from where part of the book is set, when Rebecca arrives newly in America. I’ll add more events to my website as they get scheduled. I’d love to see you at one of these events!

The post Book Tour Schedule! appeared first on Elizabeth Graver.

March 24, 2023

Why Include Family Photos in a Novel?

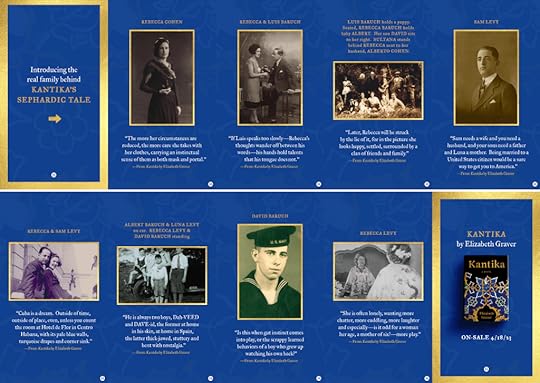

THE LOVELY PEOPLE at Henry Holt & Co. have designed a set of images that pair photos from Kantika with quotes from the book; they will post them on social media as the April 18th publication date draws near, but you can look below for a sneak peek.

Using family photographs in this novel was very important to me, even as it’s an unconventional choice and one that a few early readers balked at. I stuck with my impulse—it felt too important to ignore—and did everything I could to make it work. I wanted to blur the line between fact and fiction and invite my readers to think about the roots of the story, which in this case are with a real family (mine), even as I wanted to take liberties by imagining scenes and inner life. Writing historical fiction for me is always a dialogue—between the past and the present, between the facts I find and the things I imagine, between the work of historians, my own wanderings (I traveled to Turkey, Spain and Cuba for this book), and the clamoring voices in my head.

Because Kantika has its origins in recordings I did of my grandmother Rebecca telling stories decades ago, the dialogue in this case was literal. I think of this book, with its title that means “song” in Ladino, as a kind of duet between my grandmother and myself, though she died decades ago. I’ve used her real name, as well as the real names of several other relatives (with the permission of those who are still alive). The photos offer glimpses of the real people—their features, how they dressed, how they held their hands, looked at the photographer, looked away—even as they also show artifice or even lie. I’m interested in how they trouble the truth/fiction boundary, but also in how they work as physical objects inside the novel, where they serve as a way to hold onto family across wrenching absences created by migration but also as a kind of cold, tender—legal proof, ways to snag a husband, pass a citizenship test, get in.

It is astonishing to me that in the context of so many tumultuous journeys, my grandmother managed to preserve such a rich archive of family photographs. She must have held them close. In writing Kantika, I scrutinized them, their fronts but also their backs. One photo from 1907 Istanbul shows the insignia of a photography studio on Rue Pera, the photographer bearing an Armenian name. This turned into a scene in the novel and helped me think about the pluralistic, cosmopolitan nature of the city at the time and how that was soon, with the Armenian genocide on the near horizon, about to change. On the back of a 1934 photo of Albert and David, the young sons that Rebecca had to leave in Spain when she immigrated to New York, she wrote, “There in Spain my dollings,” her misspellings revealing her brand new English and the New York accent with which “darlings”—”dollings”—reached her ears.

The post Why Include Family Photos in a Novel? appeared first on Elizabeth Graver.

February 28, 2023

“Make an island away from all that where you can do your work.”

I fly out later today for an artists’ residency at the Dora Maar House in Ménerbes, France, where I’ll mess around with some new writing, read, hang out with my fellow resident artists—American-living-in-Berlin writer and disability rights activist Kenny Fries and Irish filmmaker Mary McGuckian—walk in the Provence countryside, and speak French. Running away to France for over a month with a new book, Kantika, due out on April 18th feels a little tricky, though with our wired world, I can stay abreast from afar. It also feels like the best thing I can do for myself in the edgy time before my newest creation—the product of nearly a decade of sometimes joyful, sometimes painful and frustrating work—comes blinking out into the light.

I was in my mid-twenties when, to my astonishment, I won the 1991 Drue Heinz Literature Prize for my first book, a story collection. The judge was the wonderful writer Richard Ford. We struck up a correspondence, and he was unfailingly generous to me as I navigated life as a young writer. In one letter to him, I kvetched about my anxieties about getting bad reviews or no reviews and having no idea how to write the next book and feeling exposed as my innermost feelings became available for public scrutiny. Richard’s response has stayed with me: “You just need to make an island away from all that where you can do your work.”

I’ve been lucky to attend several other artists’ residencies. After some early scurrying about where I nose about my new bedroom and studio like a feral cat, I always settle in. Time expands. My inner life grows bigger, the outer world smaller. I love meeting the other residents and learning about their work, and I’ve made lifelong friends and had fruitful collaborations, but more than anything, the residencies remind me how much I love to be alone. I’ve also had plenty of DIY retreat experiences, mostly with my historian friend Bridgette. We both have teaching jobs, kids, dogs, busy lives, but we figure it out, even if just for a day or two. We’ll rent an off-season AirBnB in Provincetown or a cheap hotel suite in Vermont, retreat into our own heads for hours, meet for a meal, retreat again, meet for a long walk, go write, cook together, eat, share pages and dark chocolate and strawberries after dinner. Return to our laptops, the little clicking sounds of Bridgette’s keyboard in a stuttery duet with the little clicks of mine.

I spent my junior year of college in Paris in 1984 and returned soon after to teach English in a French high school for a year, but I’ve not been back, even for a brief visit, for some fourteen years, and I’ve never been to Provence. I’ve been speaking French to myself as I walk the dog in the woods, the language at once far away and weirdly present, lodged somewhere in the back of my head. I love the cadences of it, its lilts and lifts, and the way I’m not entirely my normal self when I speak it, but rather tilted slightly differently, a little other. Lighter in speech, somehow, even as I stumble. More wry and comical, even clownish; I purse my lips; my eyebrows rise. Is it the language itself or the fact that it’s not mine? I may be more uncertain in French, but I’m also braver. Qu’est que ça veut dire? Je ne comprends pas.

La Maison Dora Maar is open for applications from mid-career artists and humanities professionals for the next residency cycle. As for me, I’m off to unzip my suitcase, peer inside, rezip.

The post “Make an island away from all that where you can do your work.” appeared first on Elizabeth Graver.

February 8, 2023

Ask the Author!

https://www.goodreads.com/author/show...

January 21, 2023

Behind Kantika: A Conversation with Elizabeth Graver

Tell me about this novel – what is Kantika about? Who are the characters?

Kantika is a story of migration, motherhood, blended families, disability and finding joy amidst tumult, as well as a homage to a vanishing culture. Inspired by my maternal grandmother, Kantika’s central protagonist shares her real name, Rebecca née Cohen Baruch Levy. My grandmother died in 1992, but a few years prior to that, when I was twenty-one, I recorded her telling stories from her life. She was born in Istanbul in 1903, into a wealthy Sephardic Jewish family. After the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, the Cohens lost their fortune and conditions worsened for Turkish Jews, and the family moved to Barcelona, a surprising destination given that centuries prior, during the Spanish Inquisition, Spain had expelled and killed the Jews or forced them to convert. There were hardly any Jews in 20th-century Spain, but the family’s home language of Ladino and many of their songs, food and customs had Spanish roots.

In the novel, as conditions worsen in Europe, especially for the Jews, Rebecca finds a way to move to New York by way of Cuba and builds a new life. I inhabit her perspective, as well as that of her father Alberto, her mother Sultana, and eventually, her son, David—a boy traumatized by having been torn from his grandparents in Spain. I also explore the point of view of Rebecca’s disabled stepdaughter, Luna, a bright, ambitious girl with whom Rebecca has a particularly intense relationship. I was fascinated by how this migration story plays out differently for different people and across generations and countries, with Rebecca always at the center. She can be difficult and exacting, but she is also lusty, creative, and determined to make a vibrant home in the world for herself and her family.

What drew you to this story?

Oh, so many things, even as it’s also a story I resisted telling for a long time, as it felt both too close to home and quite far away in terms of my lack of knowledge of many of its elements. I was raised in a culturally Jewish but secular household. I always knew that my two sets of grandparents (my paternal ones were Ashkenazi) were very different from each other in the food they ate, the languages they spoke, their religious practices, and more. I was particularly drawn to my maternal grandmother, Rebecca. She was full of song and stories and endlessly creative, always making things. She was also unconventional for her time, unusually forthright and at home in her body. As a child, I was confused about her origins. I knew she was Jewish but was she Turkish or Spanish? She talked about having been born rich, but I knew my mother had grown up in a family of modest means.

I interviewed my grandmother in my early twenties and treasured the two micro-cassettes that held her voice, especially after she died, but decades went by before I returned to her story. What made me turn to it? Several things, I think: I had gained confidence through writing my previous novel, The End of the Point, which has a big cast of characters and explores how individual lives intersect with major events in history; I was watching the worldwide refugee crisis unfold in our current moment; I was aware of the passage of time and of the generation above me growing old. My uncles David and Albert helped me with the novel—I spent some wonderful days interviewing them—but both of them sadly died before it came out. My mother, well into her eighties now, has been my steady companion at every stage. I view Kantika as a both public imagining and a private gift to my family.

Why did you decide to write this book as fiction . . .

I considered writing it as nonfiction, but there were too many holes, and I wasn’t interested in pointing them out or tracking my own position as a writer sleuthing to reconstruct the past. I’m at heart a novelist. I love to chart inner life. I didn’t expect, when I started, to imagine my way inside the heads and hearts of Alberto and Sultana—great-grandparents I never met in real life—but they called out to me: Alberto with his deep affection for Istanbul, his love of gardening, his bewilderment and bitterness at the turn his life has taken; Sultana, a caretaker, quiet in her sorrows, having to start anew at an advanced age. Soon I was deep inside truly fictional territory, while also still in conversation with the facts.

. . . and yet include family photographs?

Can’t I have it both ways? That choice, while unconventional, stems from the fact that Kantika has a relationship to a real family (mine!) and engages with an overlooked history of 20th-century immigrant Sephardic Jews whose actuality matters to me. Including photos is one way to signal this; using some real names is another. The photos offer a glimpse of reality, even as they are partial, set-up, full of artifice. Photographs also interest me in the context of migration, where they can be used as proof (a citizenship or passport photo), a memory bank (the images you carry with you when you leave loved ones behind), a form of capital and seduction (a photo sent to a potential mate for an arranged marriage), and more. In the first half of the 20th century, they were scarce and rare—so different from in our current times, when as long as you have a cellphone, you can snap and carry pictures. Photographs are also a way to think about the female body, which is a theme throughout the book. Rebecca is a dressmaker and beauty who cannily deploys her looks to fit the circumstance and pass. She loves to dress up, pose, be seen. Her stepdaughter, Luna, who has cerebral palsy and lives in an ableist, prejudiced world, has a quite different relationship to the body and being photographed.

Your research apparently involved quite extensive reading, travel and interviews. Were there any particularly exciting or interesting finds?

More than I can name, though I hope the research is folded inside the story and doesn’t show its seams! In Istanbul, I interviewed residents at the Sephardic Home for the Aged. Djentil Nahon’s character and the stories she tells, particularly a disturbing one about Spain, was inspired by a woman there. I found a 1929 film in the archives of the National Center for Jewish Film that contained unattributed footage of my family at the secret synagogue where they lived in Barcelona. That blew me away. I was aided by several scholars of Sephardic Studies, who helped me with Ladino, cultural references, and more. My family—my mother, uncles, Aunt Luna (who died before I started writing Kantika but left some writing behind)—were treasure troves of information. It was a true gift of this process to get to sit down with relatives and hear their stories. When I teach writing to college students, I’m always telling them to record their grandparents. They’ve gathered some powerful stories.

Your novel ends in 1950. How does it connect to the world we live in today?

We live in a world where migration remains a central, pressing fact, and where wars and regime changes (and now also climate change) continue to push people across the globe, often at the will of systems whose policies aren’t shaped by an underlying commitment to human rights. Xenophobia of many sorts is alive among us; antisemitism is on the rise. Families, including mothers and children, are still separated by migration, as happens in my novel. Another still-present theme is how the idea of a homeland, though powerful and necessary at times, can be deployed for colonial, nationalist or racist ends. Why does Spain occasionally (in 1925, and again in 2015; my daughter has tried, unsuccessfully, to obtain a Spanish passport) offer citizenship to Sephardic Jews but make the process so labyrinthian and costly that it’s often bound to fail?

On a more positive note, I’m interested in how the Jewish community in Turkey lived peaceably, if not without complications, in a predominantly Muslim culture for hundreds of years, after the Ottoman Empire welcomed the Jews during the Spanish Inquisition. As a child in Istanbul, my grandmother went to a French Catholic school, her classmates Muslim, Catholic and Jewish girls. She loved the nuns, had friends across creeds, and spoke of it as one of the best times of her life.

Why the title? What does it mean?

“Kantika” means “song” in Ladino, (also called Judeo-Spanish), the endangered language of the Sephardic Jews. The word invokes a rich Sephardic history of music and poetry and helps keep a beautiful, strange word in circulation. Rebecca sings throughout the novel so the title also has a literal meaning. I hope the book itself reads as a kind of song. More than a story of my own singular invention, I think of Kantika as a duet—between English and Ladino, fiction and history, the past and the present, my grandmother and myself.

The post Behind Kantika: A Conversation with Elizabeth Graver appeared first on Elizabeth Graver.

January 9, 2023

Kantika Goodreads Giveaway

https://www.goodreads.com/giveaway/sh...

Kantika

November 18, 2022

A Life Sewn from Scraps

I woke up today to find this beautiful response to Kantika from Justina Elias, a bookseller and young writer at Munro Books in Victoria, British Columbia, who posted it on her Instagram account:

Rebecca Cohen is a seamstress who will come to wear many names: one from her father, two from marriage, another from her work in 1920s Barcelona, where to flaunt Jewish ancestry is to court disaster. Hers is a life sewn from scraps, her privileged family in Istanbul torn apart by the collapse of the Ottoman Empire and the rise of anti-Semitism across Europe. Yet there is joy in piecing together a new story, one she shares with her granddaughter, Elizabeth, whose fictionalized account of her family’s journey to America is a tribute to the resilience of Sephardic women and the regenerative power of art. A lusty novel harmonizing pain and laughter, Kantika lives up to the Ladino word that gives it its name: ‘song.’

I looked up Munro Books, hoping it might actually be the bookstore that Alice Munro—who, perhaps more than any other writer, got me started writing in my twenties through her astounding stories—started with her husband Jim Munro, and it is. The current location of the store looks gorgeous—high ceilings, frescoes, light—and the thought of the Kantika finding its way there and into Justina’s hands is a gift on this chilly New England Friday in November. Writing this book has been a long journey, and publishing it is yet another one. Off we go!

The post A Life Sewn from Scraps appeared first on Elizabeth Graver.

October 1, 2022

Book Recommendation, One Hundred Saturdays, by Michael Frank

I just finished reading a quite extraordinary book, One Hundred Saturdays, by Michael Frank. The author spent seven years of Saturdays interviewing a woman named Stella Levi, who grew up in the Sephardic community of Rhodes before it was obliterated by the Nazis. Stella was among the ten percent of people who survived. She’s an extraordinary figure, complex, articulate and full of life well into her nineties.

For me, this book also felt deeply personal in how it intersects with my forthcoming novel, one inspired by my maternal grandmother, a Sephardic Jewish woman from Turkey. Both stories evoke the multilingual and cosmopolitan nature of Eastern Sephardic culture, the place of song, food, adages and healing rituals, as well as the strong pull of the modern world for a young woman. But my particular obsessions aside, this is just an incredible story. The relationship between the author and his subject is rendered in beautiful ways so that the book is, among other things, a meditation on slow listening and long friendship.

The post Book Recommendation, One Hundred Saturdays, by Michael Frank appeared first on Elizabeth Graver.

August 10, 2022

Filling the Well: Retreating to Write

I have some writer friends who get up each day at dawn to write, no matter what else is happening in their lives. While I admire their discipline, this has never been my way. Not that I’m not always percolating when I’m deep inside a book—I “write” as I drive, walk, swim across Walden Pond (inconveniently, as some good sentences spill out into the water)—but days, weeks, even months go by when I’m teaching, parenting, spending time with friends, getting out the vote, even just gardening, when I don’t sit down to write.

What I do instead, what I’ve done for decades, is make a practice of clearing out a swathe of time each year when writing can be the pulse and center of my days. Sometimes this means five days alone in February in a friend’s borrowed apartment in Provincetown, my only human interaction chatting briefly with the barista at the one open coffee shop down the street. Sometimes it means renting an Airbnb for a few days with my historian friend Bridgette. We hole away, come together for a walk or meal, retreat some more. At night we share ideas and pages. Time stretches out; I go deeper and deeper. I’m lucky to have an academic job that accommodates such ventures, as well as a partner who sends me off with his blessing. When our daughters were small, I’d leave them tiny wrapped presents, one for each day I was gone: a bar of soap, a blue marble, a little plastic cat.

Over the years, I’ve attended a few artists residencies, where the mix of uninterrupted time and the creative energy generated by being in community with other writers, composers, filmmakers and visual artists is a magic potion. I get my best work done during these residencies. Kantika took me many years to write, with lots of false starts, an enormous amount of research, and a radical revisioning of the book after I completed a polished (at least on the sentence level) draft. I finished the final draft in June of 2021 at a residency at the Marble House Project in Dorset, Vermont, where my studio sat next to a coop filled with clucking chickens and dinner table conversations were as wide-ranging and as nourishing as the meals I cooked with my fellow residents. Here is a seven minute video interview from that time, in which Danielle Epstein, the co-founder of Marble House Project, interviews me about experience there.

The post Filling the Well: Retreating to Write appeared first on Elizabeth Graver.

July 16, 2022

German Edition of Kantika

A German edition of Kantika is forthcoming from Mareverlag, the house that published The End of the Point (called Die Sommer der Porters in German). Kantika will be translated by Julianne Zaubitzer, who did such a great job with my last book. I’ve recently returned from a week in Berlin where I glimpsed the vibrant literary scene there, as well as the city’s efforts to memorialize and come to terms with the Holocaust as it played out on its streets. From the stolpersteine (stumbling stones) marking the last voluntary resident of people persecuted by the Nazis to the extraordinary tiny Museum Otto Weidt’s Workshop for the Blind, you feel the stories everywhere, often literally beneath your feet. It means a lot to me that Kantika, with its roots in a different expulsion and its Sephardic story, will become part of the conversation in Germany.

The post German Edition of Kantika appeared first on Elizabeth Graver.