Alan Watt's Blog, page 11

August 2, 2017

Shedding the Idea for Truth in Writing

It’s not just first-time novelists that struggle with getting their story from the imagination to the page. Every writer struggles with this.

Here’s the thing: Our idea of our story is never the whole story. When a writer holds onto his idea of the plot, he tends to get stuck.

By exploring the nature of what we’re attempting to express, we are led to a more dynamic version of our story.

Here’s the secret: Notice the dilemma that your protagonist is struggling with. That is the tension that carries the through-line of your novel.

The through-line does not lie in the plot, though almost every first-time writer thinks it does. It lies in the theme.

And the theme is explored through the protagonist’s attempt to resolve his dilemma.

When we understand that our protagonist’s goal is not difficult, but rather, it is impossible to achieve, we begin to shed our idea of the goal for the truth of the goal.

Just as the writer dies to his old idea of how the story should go, our protagonist experiences a loss of his old identity in order to be reborn.

Please share your thoughts.

July 31, 2017

Writing for Our Ideal Reader

Good storytelling is about having at least a somewhat conscious relationship to our ideal reader, and telling the story in the most compelling way possible. It is about understanding the most effective order of events. This is achieved through “holding the story loosely” and being willing to write and rewrite.

The process of telling a story is akin to a Polaroid coming into focus, or an alien spacecraft moving toward planet Earth — as it approaches, it sees the Earth in greater and greater detail. We began with an idea, then we imagined the world, wrote an outline, and finally bashed out a first draft. Now that we have “channeled” that initial story, we step back and become curious about the most effective way to tell it.

Let us imagine for a moment that we are the typical ruthless, yet openhearted reader. Our reader comes to the book with expectations. He wants to be taken on a journey, to be under the spell of the storyteller, in fact, our reader wishes to be seduced. The accomplished storyteller approaches his story as if it were a seduction. The accomplished storyteller never forces his will. The accomplished storyteller is sensitive to his reader, while at the same time never losing focus, always moving toward his objective.

How is this accomplished?

It is accomplished by having a grounding in basic technique, while staying open to our Source, to that primal impulse that spoke to us in the first place.

Basic technique, as far as I’m concerned, really just means maintaining an ongoing curiosity about structure, i.e., tracking the “want” through the plot points. As we grow as writers, we discover over and over again that our story is never entirely what we thought it was going to be. By being open to the structure questions, we can develop, over time, an abiding relationship to the infinite complexities of our human condition. By being open, we can become surprised at the unpredictability of human behavior. These discoveries can be frightening and thrilling all at once. Story structure is not a formula. Story structure can hold all of the complexities of the human condition. It is our job as writers to continue to be curious about our own humanity, to be willing to ask ourselves, in moments of crisis or doubt, “I wonder where this experience exists in the world of my characters?” rather than allowing ourselves to become swallowed up by our own guilt, fear, or neurosis. Let us always hold our stories loosely enough that we are willing to be surprised by our character’s choices. When we do this, we are often led to deep truths we didn’t even know we were seeking.

Please share your thoughts.

July 26, 2017

Writing When You Have Nothing to Lose

Have you ever experienced great loss? Whether it was a parent, spouse, or friend, the experience pulls you sharply into the present moment.

Nothing else matters, not the barking dog, the unpaid bills, not even your hopes and dreams.

We become utterly aware, in our bones, that despite all of our wishes, fantasies, and protestations, our loved one is never coming back — at least, not in the flesh. He or she will exist only in our memory and imagination.

It’s a shocking moment, because we live our lives with the sense that there is always more time.

In the moment of loss, we are reduced to our primal selves.

This is the same place that we create.

When we approach our work from this place, we are unafraid to express ourselves completely. We become unshakeable in our willingness to be truthful on the page, and suddenly, our simple, unadorned writing springs to life.

Please share your thoughts.

July 24, 2017

We Are The Authority Over Our Writing

It can be challenging at times to stay connected to our initial impulse. All sorts of demons can spring up in the rewrite: fear, doubt, and impatience. Sometimes we can get sidetracked by the desire to dazzle, or we can begin to question the “apparent” contradictions of our hero’s behavior and attempt to tame him, while effectively neutering the “aliveness” of our story. Our character’s motivations have nothing to do with “logic” but rather have everything to do with the human desire to get what we want. Let’s trust the wildness of our first draft as we continue to explore our through-line with greater specificity.

Remember, our hero’s want never changes, but what he wants looks very different from one point in the story to the next. We can kill the “aliveness” of our initial creation by trying to make sense of it all, rather than trusting the humanity. Our job is to support the action by exploring more deeply our hero’s motivation. When we find ourselves wondering why our hero has done something, we are on the right track. Stay curious.

What can often happen when we are finally ready to have people read our work is that these well-intentioned folk will give notes like “this part didn’t make sense,” and we will be tempted to get rid of it rather than clarifying it. Sometimes they will even say “you should get rid of it,” and because we are tired, and perhaps fearful, we will abdicate our authority over our material. This can happen so quickly, and once we have done this, we are on the road to losing connection to all of our hard won insight.

Our job as writers is to be the final authority over our work. We are the parent of our creation. No matter who the note-giver is, they can never fully know the story that dwells in our heart. If we ever make changes to our work without first asking ourselves what the underlying reason was for the moment or the scene, we are abdicating our authority. This is crucial to keep in mind, and here is how we know we are abdicating our power: We are feeling uneasy. We must listen to this. We can have a tendency to numb out and ignore it, because we want to be done. We must trust the story that lives within. We will be rewarded in publishing heaven, even if it is our publisher who is giving us the notes. I’m not suggesting we be belligerent or difficult, but we must be ready to defend (at least, for ourselves) what we are attempting to express. (This may not even involve a conversation with the other person. We can just nod our head and thank them for the notes). Oftentimes we may be unable to articulate what we are attempting to express, and that is just fine. We cannot afford losing something essential for the sake of expediency. Don’t throw the baby out with the bathwater. (This is also why we don’t want our work to be read by anyone else until we have done all we can do with it. It is the sign of an amateur to ask for notes when he is not done.

There can also be a desire to want to erase something because we don’t quite understand it, or we fear that we are not up to the task of making it clear. When we are faced with this, the more challenging choice is the only choice. We must stay with it, be patient, and trust that our unconscious will resolve it in time.

Sometimes what we write is so personal that we fear nobody will understand. Again, and again, as I work with writers, we discover that this is the sweet spot. When we start to feel just a little too exposed, we are hitting pay dirt. Tapping into the universal is terrifying, but also liberating. It can feel uncomfortable because it is unfamiliar, but as we stay with it, clarity will prevail. The truth is in there, and it is always worth the investigation.

Please share your thoughts.

July 19, 2017

“What do I do when I get stuck in my story?”

When writers come to a dead stop there can be a tendency to panic.

It’s important to remember that our idea of our story is never the whole story. When we try to figure it out, we tend to dig a deeper hole.

Story is alchemy. As our novel progresses it becomes something else entirely, and when we hold onto our initial idea, we reach a point where we can’t move forward.

Here’s the solution. Rather than looking at the “apparent problem” that your protagonist is struggling with, notice that underneath it lies a dilemma. By exploring the nature of this dilemma, you will be led to a deeper understanding of the character.

Character suggests plot.

By exploring the character’s dilemma, plot will emerge, and you will get to the end of your story.

Let me know your thoughts.

July 17, 2017

Writing Despite Fear of Criticism

Every open heart has an Antagonist

When Gustavo Dudamel became the youngest conductor of a major orchestra, an L.A. Time’s journalist urged us not to get too excited about our newest conductor, counseling us that he was still young and unproven, that we should not rush to anoint him genius quite yet.

Dudamel is not an ignorant man. He is aware of the dangers of leading with his heart. When a spirit rises up to express its true self, there is an aspect of our collective humanity that wants to test it. It takes courage to lay ourselves bare. There is nothing to hide behind, no cloak of cynicism to shroud our timidity. Dudamel is not impervious to criticism, yet he chooses to make himself vulnerable, to be moved in spite of the potential public blowback. What if Dudamel read the criticism and decided (unconsciously or not) to be more emotionally careful, that the cost of public scrutiny was not worth his bruised ego. In a creative life, the fear of embarrassment can threaten us at every turn. We may feel the pull to lower our vision, to withdraw, to be reasonable, practical, sensible, and all those other words that masquerade as maturity but are really just euphemisms for fear. As artists, it is important that we do not underestimate the antagonistic forces we face in the act of creation. Our fears are not unfounded, insofar as we have evidence to support them. And if we face them head on, the antagonistic forces will win. After all, they are armed with libraries of proof . . . they have history on their side. The desire to transform means risking everything we think we know for something beyond our imagining.

By taking the risk of allowing ourselves to be used as a channel we become targets for every blocked artist, every cynic and naysayer for miles around. Wisdom comes from knowing this, and protecting our creation by not discussing it while it is being borne, so that we can get down into our story and really let it rip. We cannot wait for everyone to support our endeavor. We cannot wait for everyone to approve of what we have to say. We cannot wait for our security to be guaranteed, or for victory to be certain. We alone know what the truth is, in spite of the voices in our heads telling us otherwise. There is no time to settle a score. There is nothing to win. All of the reason our antagonists can muster is no match for our open heart.

Let me know your thoughts.

July 12, 2017

Overcoming Writer’s Block: Exploring the Dilemma

It’s not just first-time novelists that get stuck. Every writer, except Stephen King, experiences writer’s block.

Writer’s block is often an absence of information. The information can be related to character or theme, though the writer usually believes that the stuckness is related to plot. It isn’t.

Plot arises from character, and characters are in service to our theme or central dilemma.

By exploring the dilemma that your characters are struggling with (and they are all struggling with an aspect of the same dilemma — because the purpose of story is to resolve a theme), conflicts will naturally arise and present you with situations that you might not have otherwise considered.

The challenge for the authors in overcoming writer’s block is in understanding that our idea of our story is not the whole story. By exploring the dilemma, we’ll begin to explore new ways of seeing the “apparent problem” and we’ll begin to see our story in a more dynamic way.

Let me know your thoughts.

July 10, 2017

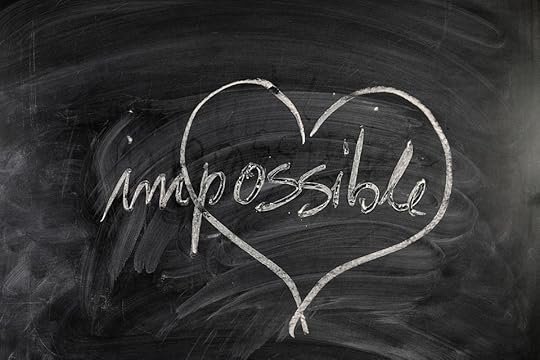

The Write Process: Making the Impossible Possible

“A problem cannot be solved with the same level of awareness that created it”

— Albert Einstein

We often have an idea of the direction our story is going, and sometimes we discover that, in fact, it does head in that direction, but not in the way we had anticipated. To some degree, we are our hero’s journey. This is part of what makes this process so thrilling and meaningful, and also makes it feel so fraught with the potential for ‘failure’. On some level, we are exploring our own life, and making ‘supposed’ meaning out of what we discover. The urgent need that initially roused us to write our story seems to come up for review, and we are invited to question all of our beliefs.

Fears arise, and our challenge is to remain curious, while not making meaning out of these fears, as we may have in the past. We understand, in some fundamental way, that what we had made meaning of was not the whole truth. It did not include the possibility for something greater, for something perhaps beyond our imagination. It did not include grace. This is the magic of story. Story structure is a wonder of the universe, and as evolving creatures, we are eternally drawn to its power, because a working relationship to story actually has the effect of stretching our imaginations, inviting us to explore areas that are actually beyond what we thought we knew.

It is one thing to talk about this process, though quite another to stand in its power. We can talk about the power of a tsunami, but being there is a different experience. The willingness to shepherd our hero through the crucible of surrender and awakening, with the clear brave eyes of a curious writer usually involves just a little more bravery than we currently possess. It does seem almost impossible at times, doesn’t it? In fact, I believe it is. I can’t do it. And the moment I realize this, everything shifts and I discover that I am merely a channel. If it was up to me, I would continue to circle the airport of my neurosis. It is my higher self that steers the ship. All that I need is within. My job is simply to inquire.

Let me know your thoughts.

July 5, 2017

Procrastination Masquerading as Research

I work with first-time novelists all the time who desperately want to convince me that they can’t begin their first draft until they do more research.

Research is important, and it’s also misunderstood.

Particularly in fiction, we are more interested in the characters in relationship to each other than we are in the minutiae.

It’s not that we don’t care about the details, it’s just that the research process AFTER you have written the first draft of your novel is far simpler than the one that precedes it.

After you’ve written your first draft, you tend to have clarity about the research necessary to provide the world with the stink of reality.

Much of the research that precedes the first draft of your novel is just procrastination.

Let me know your thoughts.

July 3, 2017

The Write Process: What is my title?

Those scant few words on the cover of our book or screenplay can be the most labor-intensive work of our entire manuscript. Coming up with a good title can be a bitch. We may have a working title, a place-holder, while we wait for that perfect title to jolt us awake at three in the morning. Sometimes a title is only great in retrospect. There is nothing particularly poetic or provocative about The Great Gatsby, until you learn that Fitzgerald’s original title was Trimalchio of West Egg.

A Moveable Feast is evocative. It captures our imagination; we want to know more. Same with Lonesome Dove, Catcher In the Rye, Angle of Repose. A good title can speak directly to our theme, like Ha Jin’s Waiting, or it can be blunt, grand, and in your face like Martin Amis’ Money, as if this were the final word on the topic. There are poetic titles like Carlos Ruiz Zafon’s The Shadow of the Wind, or Charles Baxter’s The Feast of Love. In the past twenty years, artists have loved putting America in the titles of their work. American Psycho, American Pastoral, American Buffalo, American Idiot, American Gods. The American Revolution has had many books written about it, yet strangely they rarely have the word America in the title: The Glorious Cause, Almost A Miracle, and others. E.R. Frank recently published a young adult novel entitled simply America (which, as coincidence would have it, is the protagonist’s first name).

Generation is another popular word. Everyone, it seems, is looking to coin the next movement. Generation X, Generation Y, the ME generation, and recently Evan Wright’s quite successful Generation Kill.

Obviously, the goal is to get the reader’s attention. Book titles are the literary equivalent of trying to look like you know what you’re doing in hopes of getting picked for the team. There are no rules for book titles. Tell the story as best you can, and if it’s great, even a mundane title like The Great Gatsby isn’t going to hurt it.

Let me know your thoughts.