H. Lee Cheek Jr.'s Blog, page 5

December 5, 2013

Christmas With A Point

We need not assume the mantle of an anti-materialist to appreciate that a certain degree of social equilibrium is dismissed or ignored during the holidays, allowing for a lack of societal and personal restraint. Many otherwise normal considerations are subsumed into the pursuit of a "happy" holiday. All too often this demands we forgo normal obligations and long-held practices in the pursuit of temporal exuberance. Of course, the holy seasons of Advent and Christmas are typically approached with a spirit of reverence and excitement, but when inherited customs are displaced, we provide an opportunity for other influences to prevail. A cherished, but potentially wearisome tradition that can become corrupted is the giving of gifts. The best gifts should encourage the family member or friend to live life to the fullest extent possible, while also pursuing the higher potentialities of their existence and their faith.

After decades of giving presents that were usually dispensed with, or discarded in a few days, or "regifted" to aid another's frenzied pursuits, I became determined to give gifts with a point, or at least gifts that would connect the recipient with the larger social and political tradition of which they are part. The gifts that are most likely to endure and fulfill the stated goal are books and fountain pens. Gissing’s Ryecroft preferred books to food, a great book as a gift can provide sustenance that no other gift can. A fountain pen reminds us of the power of writing, allows the writer to engage in his or her craft with a closeness unmatched by a keyboard or ballpoint, and is a novel and exceedingly pleasurable gift for anyone. Here are some gifts with a point you might want to consider:

1-André Gushurst-Moore’s The Common Mind (Angelico Press, 2013) provides an elegantly written and philosophically convincing survey of the worldview Burke inherited and that he helped transmit to posterity. The common mind, or Christian humanism, is understood from both the perspective of a philosophical inheritance and as a perpetual challenge to contemporary life as well; as a social and political tradition dependent on the ennobling of the good, the true, and beautiful; and, the exhibition of personal restraint, and an affirmation of the transcendent nature of existence. Gushurst-Moore begins his defense of this tradition by engaging in a process of retrogression, examining the central figures who affirmed the common mind, beginning with Thomas More and concluding with Russell Kirk.

2-The new edition of Russell Kirk’s Prospects for Conservatives, the first imprint of ImaginativeConservative Books, should be on every Christmas list! The tome contains a new introduction by Dr. Brad Birzer, and a new subtitle. As one who possessed the largest and last remaining collection of the earlier version of this book, A Program for Conservatives, and shared the books with his Duke Divinity School colleagues in the early 1980s (much to their dismay), this republication is an event of great and enduring importance. (For the record, I gave the remaining hundred copies of the book that I purchased from a centenarian in California to the Russell Kirk Center for Cultural Renewal.)

2-The new edition of Russell Kirk’s Prospects for Conservatives, the first imprint of ImaginativeConservative Books, should be on every Christmas list! The tome contains a new introduction by Dr. Brad Birzer, and a new subtitle. As one who possessed the largest and last remaining collection of the earlier version of this book, A Program for Conservatives, and shared the books with his Duke Divinity School colleagues in the early 1980s (much to their dismay), this republication is an event of great and enduring importance. (For the record, I gave the remaining hundred copies of the book that I purchased from a centenarian in California to the Russell Kirk Center for Cultural Renewal.) [image error]

3-Of interest to students of theology, regardless of one’s persuasion, is yet another monumental contribution by Thomas C. Oden. John Wesley’s Teaching: Volume 3, Pastoral Theology (Zondervan, 2013) affirms Wesley as a central figure in the Reformation, but more importantly, as a defender of classical, consensual Christianity.

3-Of interest to students of theology, regardless of one’s persuasion, is yet another monumental contribution by Thomas C. Oden. John Wesley’s Teaching: Volume 3, Pastoral Theology (Zondervan, 2013) affirms Wesley as a central figure in the Reformation, but more importantly, as a defender of classical, consensual Christianity.  4-If you seek to recover the lost world of prudential political rhetoric, and a time when statesmen outnumbered politicians, you might want to take at Patrick Henry-Onslow Debate: Liberty and Republicanism in American Political Thought(Lexington Books, 2013). The disputed election of 1824 was one of the most important presidential elections in American history. After an indecisive electoral college vote, the House of Representatives selected John Quincy Adams as president over the more popular war hero, Andrew Jackson. As a result, John C. Calhoun ended up serving as vice-president under Adams. Neither man was comfortable in this situation as they were political rivals who held philosophically divergent views of American constitutional governance. The emerging personal and philosophical dispute between President Adams and Vice-President Calhoun eventually prompted the two men to take up their pens, using the pseudonyms “Patrick Henry” and “Onslow,” in a public debate over the nature of power and liberty in a constitutional republic. The great debate thus arrayed Calhoun’s Jeffersonian republican vision of constitutionally restrained power and local autonomy against Adams’s neo-Federalist republican vision which called for the positive use of inherent power—a view that would become increasingly compelling to future generations of Americans. In the course of this exchange some of the most salient issues within American politics and liberty are debated, including the nature of political order, democracy, and the diffusion of political power. The level of erudition and insight is remarkable.

4-If you seek to recover the lost world of prudential political rhetoric, and a time when statesmen outnumbered politicians, you might want to take at Patrick Henry-Onslow Debate: Liberty and Republicanism in American Political Thought(Lexington Books, 2013). The disputed election of 1824 was one of the most important presidential elections in American history. After an indecisive electoral college vote, the House of Representatives selected John Quincy Adams as president over the more popular war hero, Andrew Jackson. As a result, John C. Calhoun ended up serving as vice-president under Adams. Neither man was comfortable in this situation as they were political rivals who held philosophically divergent views of American constitutional governance. The emerging personal and philosophical dispute between President Adams and Vice-President Calhoun eventually prompted the two men to take up their pens, using the pseudonyms “Patrick Henry” and “Onslow,” in a public debate over the nature of power and liberty in a constitutional republic. The great debate thus arrayed Calhoun’s Jeffersonian republican vision of constitutionally restrained power and local autonomy against Adams’s neo-Federalist republican vision which called for the positive use of inherent power—a view that would become increasingly compelling to future generations of Americans. In the course of this exchange some of the most salient issues within American politics and liberty are debated, including the nature of political order, democracy, and the diffusion of political power. The level of erudition and insight is remarkable. 5. The Noble Fountain Pen. My most pointed recommendation concerns the gift of a fountain pen during this holy season. I prefer vintage pens, especially the old American varieties, Sheaffer, Waterman, and Parker among many others. There are many traditional pen stores throughout the country that deserve commendation, and one of the best kept secrets in the Southeast is Joe Rodgers Office Supply in Cleveland, Tennessee, in the Chattanooga suburbs. The owner, Greg Serum, offers the best supply of fountain pens and supplies you will encounter. On-line sites worth visiting include:

www.fountainpenhospital.com

www.fahrneyspens.com

www.penhero.com

Penhero.com has an encyclopedic list of pen-related links as well that are of great assistance to anyone interesting in fine writing instruments: http://penhero.com/PenBookmarks.htm.

Published on December 05, 2013 10:06

October 25, 2013

Celebrating Russell Kirk's Conservative Mind!

The Conservative Mind’s Continuing Relevance at Sixty

by

Lee Cheek

by H. Lee Cheek

The Conservative Mind by Dr. Russell Kirk, which celebrates its 60th anniversary this year, still exerts considerable influence over the intellectual elements of American Conservatism. Dr. H. Lee Cheek delivers a lecture on this book as a for The McConnell Center at the University of Louisville's "Milestones of the 20th Century: Democracy in America" lecture series.This is part of a series The Imaginative Conservative is publishing in honor of the sixtieth anniversary of Russell Kirk’s The Conservative Mind. Essays in the series may be found here.Books mentioned in this lecture may be found in The Imaginative Conservative Bookstore. Read more of this post

The Conservative Mind’s Continuing Relevance at Sixty

by

Lee Cheek

by H. Lee Cheek

The Conservative Mind by Dr. Russell Kirk, which celebrates its 60th anniversary this year, still exerts considerable influence over the intellectual elements of American Conservatism. Dr. H. Lee Cheek delivers a lecture on this book as a for The McConnell Center at the University of Louisville's "Milestones of the 20th Century: Democracy in America" lecture series.This is part of a series The Imaginative Conservative is publishing in honor of the sixtieth anniversary of Russell Kirk’s The Conservative Mind. Essays in the series may be found here.Books mentioned in this lecture may be found in The Imaginative Conservative Bookstore. Read more of this postLee Cheek | October 23, 2013 at 4:01 pm | URL: http://wp.me/p3FGHd-7Kz

Published on October 25, 2013 11:51

October 1, 2013

Excellent New History of Political Thought

Nemo, Philippe, A History of Political Ideas from Antiquity to the Middle Ages (Duquesne University Press, 2013)

As the first part of a two volume survey of political thought, Nemo (ESCP Europe) approaches the field of study in a manner different from many American texts. Appealing to readers with “little prior knowledge” (viii) of political thought, the author provides a lucid, engaging introductory volume that will enlighten both the novice and the specialist. The use of “historical context” (ix), combined with exceedingly accurate interpretations of primary texts, and the absence of ideological frameworks, contributes to the high overall quality of the book. The work is divided into three long sections: Part One, Ancient Greece; Part Two, Rome; and Part Three, the Christian West. In the introduction to Part Three a survey to the “political ideas” of the Bible is provided, including an accessible overview of Hebrew political thought. Important, yet often neglected figures in Christian political thought, including Tertullian, Origen, and many other thinkers, are analyzed succinctly, yet thoughtfully. This valuable and readable book deserves a wide readership.

Published on October 01, 2013 05:27

September 26, 2013

Cheek on Kirk's "The Conservative Mind"

Published on September 26, 2013 11:22

September 23, 2013

AHI Fellow Lee Cheek Edits Book on the Great “Onslow” Debate

http://theahi.org/2013/09/04/ahi-fellow-lee-cheek-edits-book-on-the-great-%E2%9Conslow%E2%9D-debate/

On September 4, 2013, in News & Events, by AHI Staff The Alexander Hamilton Institute for the Study of Western Civilization (AHI) congratulates AHI Senior Fellow, H. Lee Cheek, on the publication of Patrick Henry-Onslow Debate: Liberty and Republicanism in American Political Thought (Lexington Books, 2013). Dr. Cheek co-edited the volume, which gathers documents on one of the most momentous political debates about the meaning of republican government in the decades before the Civil War.

The debate followed the disputed Election of 1824. After an indecisive electoral college vote, the House of Representatives selected John Quincy Adams as president over the more popular war hero, Andrew Jackson. As a result, John C. Calhoun ended up serving as vice-president under Adams. Neither man was comfortable in this situation as they were political rivals who held philosophically divergent views of American constitutional governance. The emerging personal and philosophical dispute between President Adams and Vice-President Calhoun eventually prompted the two men (and Adams’s political supporters) to take up their pens, using the pseudonyms “Patrick Henry” and “Onslow,” in a public debate over the nature of power and liberty in a constitutional republic.

“The great debate,” notes Kevin Gutzman of Western Connecticut State University, a recent guest of the AHI, “arrayed Calhoun’s Jeffersonian republican vision of constitutionally restrained power and local autonomy against Adams’s neo-Federalist republican vision which called for the positive use of inherent power—a view that would become increasingly compelling to future generations of Americans.” The debate between Vice President John C. Calhoun (‘Onslow’) and President John Quincy Adams or his ally (‘Patrick Henry’) captures the clash between Jeffersonian and Hamiltonian views at a pivotal moment in American history.

While the debate has not received the scholarly attention it deserves, the publication of this new book will reawaken interest in the vital dialogue. The volume also features a blurb from AHI Charter Fellow Robert Paquette: “The debate between ‘Patrick Henry’ and ‘Onslow,’ said Paquette, “fought out in the pages of Washington newspapers in 1826, speaks to the idea of competing visions, present at the founding of the United States, of republican government. The editors of this timely volume return us to a lost world in which a seemingly small incident in the Senate could spark within the highest levels of government a deep and candid public analysis of the dialectic of liberty and power and its relation to the problem of limited government. Cheek and company deserve applause for this illuminating act of recovery.”

Dr. Cheek is Chairman and Professor of the Department of Political Science, East Georgia State College, in Swainsboro, Georgia. His many publications include Calhoun and Popular Rule (2001).

Published on September 23, 2013 05:32

September 17, 2013

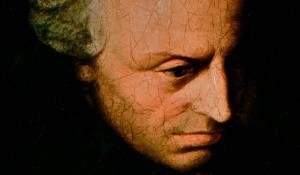

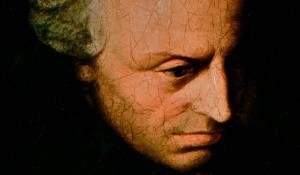

Kant's Folly

http://www.theimaginativeconservative.org/2013/09/kant-on-history-and-culture.html#more-27162

Kant on History and Culture as a Means to Ethical EvolutionSeptember 17, 2013 By Lee Cheek by H. Lee Cheek, Jr.

The “Conjectural Beginning of Human History”[1] is Kant’s attempt to recast the creation story of Genesis. The procreative act of Yahweh is cooperative in the sense heaven and earth are combined, as well as the essence of the Divine and humankind. According to Genesis 2:4, creation is the work of generations (toldoth); however, Kant’s creation is presented as a single, direct act; this account varies substantially from the complex series of events presented in the Book of Genesis which also contain a multiplicity of creative acts–and they are all the result of divine intervention. Kant prefers to change the circumstances of the origin of creation, making his essay a revolutionary enterprise. He inserts a “plan” whereby we can only improve out proverbial lot in life through individual efforts. On the other hand, the Biblical narrative allows us to possess most human facilities from the moment we enter the garden. As the result of the Fall, Kant decides to present humankind as moving from a beastlike state to a more civilized condition. The simple eidos of the account in Genesis takes the form of an ontological understanding of the universe; human existence becomes connected with the symbolization of creation. Kant’s creation narrative is a rejection of this aspect of the Biblical tradition, although as Stanley Rosen suggests, it provides Kant with a propitious opportunity to give his own version of the event.[2] The division Kant has chosen (Genesis 2-6) cannot be separated from a more substantial tradition. Kant has learned a tactic from the greatest manipulator of Genesis, Sir Robert Filmer, who used the initial chapter of Genesis to defend divine right monarchy. In due course, Locke, Sidney and others would refute this exploitation of the text, and deliver their own distortions of various sorts. Filmer and Kant commit the same error. The books Genesis to Joshua (Hexateuch), in their present form, constitute an immense, connected narrative. In either case, wherever one begins, the reader must keep in mind the narrative as a whole, and the contexts into which all the individual parts fit, and from which they are to be understood. Kant’s enterprise is based upon a denigration of the theophanic event, as it is traditionally understood. To dismiss the most important historical factors that are introduced as “intermediate causes,” Kant argues, is to “originate an historical account from conjectures alone.”[3] The result of such an approach is to present “a mere piece of fiction.”[4] God expresses Himself through His actions and these events are evidenced by the instances where we are told “God knew” of the situation in the garden, although in Kant’s account the garden is the result of a bountiful nature instead of a procreative action of the Divine. The Biblical account of Genesis presents God as always participating in human history and maintaining a desire to improve the lot of humanity, albeit God does not always take an active role in these activities. The revelatory acts Kant disparages in his “history” are the most prominent examples of the continuation of the Berith that can be found in Genesis and the Hebrew Bible. The precursor to a covenant is renewed and ratified at various intervals throughout the book; the mutual presence of God and humankind in the dialogue Kant has chosen to exegete is expanded into the mutual presence of God and his people. Kant and many contemporary biblical scholars argue that the structure and presentation of the creation idea are part of a cosmological world responding to the problems it was forced to encounter. Cosmological humans, from this perspective, did not possess the modern tools of explanation and were forced to depend on this vocabulary. The “story” presented in the first two chapters of Genesis is part of a larger canon of explanations of the universe. The Genesis story should be considered along with the Babylonian epic and other Memphite works as accounts that attempt to illuminate the creative act. Unfortunately, Kant and his epigones have failed to appreciate the reality of the event, and he is unsuccessful at reintroducing his version of a symbolic explication. Kant insinuates his solution to the “inevitable conflict between culture and the human species” when he satires Herder’s most ancient “document” of the human race by referring to it as the ancient “part” of human existence: contentment with Providence.”[5] What then follows comes into being through a process of nature, and the movement can generally be said to be from the natural to the moral. This more highly differentiated “justification of nature”[6] called providence diverges significantly from the Christian idea of providence as the foreknowledge of the Divine used in a way to protect His people on earth. The use of nature also takes on a more regimented meaning, implying it may be teleological in form. Providence must then be understood as the role of Kantian nature in history.[7]Although Kant is influenced by Rousseau, he rejects Rousseau’s philosophy of history. For Kant, human history is a transition directly related to an “analogy of nature.”[8] He argues that the original state of humankind cannot be denied, but he suggests it is not a state of crudeness because nature “has already taken mighty steps in the skillful use of its powers.”[9] Kant then proceeds to acknowledge the movement from natural instinct alone to a new state of power. Kant observed that the development of humankind as a moral lot could ameliorate the conflict between culture and species. Humankind for Kant can be considered to be developing towards a healthy end: humans alone are able to move beyond a brutish state of existence to a more humane life. But humanity is faced with at least three different types of dissatisfactions related to this new freedom. Natural maturity precedes civil maturity. While a young person may possess the physical ability to procreate and raise a family, he or she does not usually have the “civil” qualifications for another ten years, according to Kant. This is alleviated as humans develop into ethical beings, but there will be an intermittent period of misery. Kant introduces the limitation of age as prohibiting humankind from achieving our moral potential. This is followed by the problem of human inequality and the imposition of a “civil right” as the solution to the problem.[10] Albeit flawed, Kant can now provide the distinctions that are necessary to make his approach coherent. The situation becomes even more complicated when the foundation of moral education, culture, is unable to fulfill its role in society. Culture, in a Kantian context, should be understood not as an aesthetic pursuit of the good, the true, and the beautiful, but as overarching basis for the moral improvement of all humans. Culture can provide for human freedom if it can transcend nature. Culture is incapable of changing the original needs of humankind, as its success is limited to the manufactured desires resulting from humankind’s use of reason. At the end of the day, we have some form of civil society, premised upon autonomous decision-making (avoiding the “heteronomy of the will”) that resembles our inordinate faith in reason as the guide to the moral life.

The “Conjectural Beginning of Human History”[1] is Kant’s attempt to recast the creation story of Genesis. The procreative act of Yahweh is cooperative in the sense heaven and earth are combined, as well as the essence of the Divine and humankind. According to Genesis 2:4, creation is the work of generations (toldoth); however, Kant’s creation is presented as a single, direct act; this account varies substantially from the complex series of events presented in the Book of Genesis which also contain a multiplicity of creative acts–and they are all the result of divine intervention. Kant prefers to change the circumstances of the origin of creation, making his essay a revolutionary enterprise. He inserts a “plan” whereby we can only improve out proverbial lot in life through individual efforts. On the other hand, the Biblical narrative allows us to possess most human facilities from the moment we enter the garden. As the result of the Fall, Kant decides to present humankind as moving from a beastlike state to a more civilized condition. The simple eidos of the account in Genesis takes the form of an ontological understanding of the universe; human existence becomes connected with the symbolization of creation. Kant’s creation narrative is a rejection of this aspect of the Biblical tradition, although as Stanley Rosen suggests, it provides Kant with a propitious opportunity to give his own version of the event.[2] The division Kant has chosen (Genesis 2-6) cannot be separated from a more substantial tradition. Kant has learned a tactic from the greatest manipulator of Genesis, Sir Robert Filmer, who used the initial chapter of Genesis to defend divine right monarchy. In due course, Locke, Sidney and others would refute this exploitation of the text, and deliver their own distortions of various sorts. Filmer and Kant commit the same error. The books Genesis to Joshua (Hexateuch), in their present form, constitute an immense, connected narrative. In either case, wherever one begins, the reader must keep in mind the narrative as a whole, and the contexts into which all the individual parts fit, and from which they are to be understood. Kant’s enterprise is based upon a denigration of the theophanic event, as it is traditionally understood. To dismiss the most important historical factors that are introduced as “intermediate causes,” Kant argues, is to “originate an historical account from conjectures alone.”[3] The result of such an approach is to present “a mere piece of fiction.”[4] God expresses Himself through His actions and these events are evidenced by the instances where we are told “God knew” of the situation in the garden, although in Kant’s account the garden is the result of a bountiful nature instead of a procreative action of the Divine. The Biblical account of Genesis presents God as always participating in human history and maintaining a desire to improve the lot of humanity, albeit God does not always take an active role in these activities. The revelatory acts Kant disparages in his “history” are the most prominent examples of the continuation of the Berith that can be found in Genesis and the Hebrew Bible. The precursor to a covenant is renewed and ratified at various intervals throughout the book; the mutual presence of God and humankind in the dialogue Kant has chosen to exegete is expanded into the mutual presence of God and his people. Kant and many contemporary biblical scholars argue that the structure and presentation of the creation idea are part of a cosmological world responding to the problems it was forced to encounter. Cosmological humans, from this perspective, did not possess the modern tools of explanation and were forced to depend on this vocabulary. The “story” presented in the first two chapters of Genesis is part of a larger canon of explanations of the universe. The Genesis story should be considered along with the Babylonian epic and other Memphite works as accounts that attempt to illuminate the creative act. Unfortunately, Kant and his epigones have failed to appreciate the reality of the event, and he is unsuccessful at reintroducing his version of a symbolic explication. Kant insinuates his solution to the “inevitable conflict between culture and the human species” when he satires Herder’s most ancient “document” of the human race by referring to it as the ancient “part” of human existence: contentment with Providence.”[5] What then follows comes into being through a process of nature, and the movement can generally be said to be from the natural to the moral. This more highly differentiated “justification of nature”[6] called providence diverges significantly from the Christian idea of providence as the foreknowledge of the Divine used in a way to protect His people on earth. The use of nature also takes on a more regimented meaning, implying it may be teleological in form. Providence must then be understood as the role of Kantian nature in history.[7]Although Kant is influenced by Rousseau, he rejects Rousseau’s philosophy of history. For Kant, human history is a transition directly related to an “analogy of nature.”[8] He argues that the original state of humankind cannot be denied, but he suggests it is not a state of crudeness because nature “has already taken mighty steps in the skillful use of its powers.”[9] Kant then proceeds to acknowledge the movement from natural instinct alone to a new state of power. Kant observed that the development of humankind as a moral lot could ameliorate the conflict between culture and species. Humankind for Kant can be considered to be developing towards a healthy end: humans alone are able to move beyond a brutish state of existence to a more humane life. But humanity is faced with at least three different types of dissatisfactions related to this new freedom. Natural maturity precedes civil maturity. While a young person may possess the physical ability to procreate and raise a family, he or she does not usually have the “civil” qualifications for another ten years, according to Kant. This is alleviated as humans develop into ethical beings, but there will be an intermittent period of misery. Kant introduces the limitation of age as prohibiting humankind from achieving our moral potential. This is followed by the problem of human inequality and the imposition of a “civil right” as the solution to the problem.[10] Albeit flawed, Kant can now provide the distinctions that are necessary to make his approach coherent. The situation becomes even more complicated when the foundation of moral education, culture, is unable to fulfill its role in society. Culture, in a Kantian context, should be understood not as an aesthetic pursuit of the good, the true, and the beautiful, but as overarching basis for the moral improvement of all humans. Culture can provide for human freedom if it can transcend nature. Culture is incapable of changing the original needs of humankind, as its success is limited to the manufactured desires resulting from humankind’s use of reason. At the end of the day, we have some form of civil society, premised upon autonomous decision-making (avoiding the “heteronomy of the will”) that resembles our inordinate faith in reason as the guide to the moral life.

Kant on History and Culture as a Means to Ethical EvolutionSeptember 17, 2013 By Lee Cheek by H. Lee Cheek, Jr.

The “Conjectural Beginning of Human History”[1] is Kant’s attempt to recast the creation story of Genesis. The procreative act of Yahweh is cooperative in the sense heaven and earth are combined, as well as the essence of the Divine and humankind. According to Genesis 2:4, creation is the work of generations (toldoth); however, Kant’s creation is presented as a single, direct act; this account varies substantially from the complex series of events presented in the Book of Genesis which also contain a multiplicity of creative acts–and they are all the result of divine intervention. Kant prefers to change the circumstances of the origin of creation, making his essay a revolutionary enterprise. He inserts a “plan” whereby we can only improve out proverbial lot in life through individual efforts. On the other hand, the Biblical narrative allows us to possess most human facilities from the moment we enter the garden. As the result of the Fall, Kant decides to present humankind as moving from a beastlike state to a more civilized condition. The simple eidos of the account in Genesis takes the form of an ontological understanding of the universe; human existence becomes connected with the symbolization of creation. Kant’s creation narrative is a rejection of this aspect of the Biblical tradition, although as Stanley Rosen suggests, it provides Kant with a propitious opportunity to give his own version of the event.[2] The division Kant has chosen (Genesis 2-6) cannot be separated from a more substantial tradition. Kant has learned a tactic from the greatest manipulator of Genesis, Sir Robert Filmer, who used the initial chapter of Genesis to defend divine right monarchy. In due course, Locke, Sidney and others would refute this exploitation of the text, and deliver their own distortions of various sorts. Filmer and Kant commit the same error. The books Genesis to Joshua (Hexateuch), in their present form, constitute an immense, connected narrative. In either case, wherever one begins, the reader must keep in mind the narrative as a whole, and the contexts into which all the individual parts fit, and from which they are to be understood. Kant’s enterprise is based upon a denigration of the theophanic event, as it is traditionally understood. To dismiss the most important historical factors that are introduced as “intermediate causes,” Kant argues, is to “originate an historical account from conjectures alone.”[3] The result of such an approach is to present “a mere piece of fiction.”[4] God expresses Himself through His actions and these events are evidenced by the instances where we are told “God knew” of the situation in the garden, although in Kant’s account the garden is the result of a bountiful nature instead of a procreative action of the Divine. The Biblical account of Genesis presents God as always participating in human history and maintaining a desire to improve the lot of humanity, albeit God does not always take an active role in these activities. The revelatory acts Kant disparages in his “history” are the most prominent examples of the continuation of the Berith that can be found in Genesis and the Hebrew Bible. The precursor to a covenant is renewed and ratified at various intervals throughout the book; the mutual presence of God and humankind in the dialogue Kant has chosen to exegete is expanded into the mutual presence of God and his people. Kant and many contemporary biblical scholars argue that the structure and presentation of the creation idea are part of a cosmological world responding to the problems it was forced to encounter. Cosmological humans, from this perspective, did not possess the modern tools of explanation and were forced to depend on this vocabulary. The “story” presented in the first two chapters of Genesis is part of a larger canon of explanations of the universe. The Genesis story should be considered along with the Babylonian epic and other Memphite works as accounts that attempt to illuminate the creative act. Unfortunately, Kant and his epigones have failed to appreciate the reality of the event, and he is unsuccessful at reintroducing his version of a symbolic explication. Kant insinuates his solution to the “inevitable conflict between culture and the human species” when he satires Herder’s most ancient “document” of the human race by referring to it as the ancient “part” of human existence: contentment with Providence.”[5] What then follows comes into being through a process of nature, and the movement can generally be said to be from the natural to the moral. This more highly differentiated “justification of nature”[6] called providence diverges significantly from the Christian idea of providence as the foreknowledge of the Divine used in a way to protect His people on earth. The use of nature also takes on a more regimented meaning, implying it may be teleological in form. Providence must then be understood as the role of Kantian nature in history.[7]Although Kant is influenced by Rousseau, he rejects Rousseau’s philosophy of history. For Kant, human history is a transition directly related to an “analogy of nature.”[8] He argues that the original state of humankind cannot be denied, but he suggests it is not a state of crudeness because nature “has already taken mighty steps in the skillful use of its powers.”[9] Kant then proceeds to acknowledge the movement from natural instinct alone to a new state of power. Kant observed that the development of humankind as a moral lot could ameliorate the conflict between culture and species. Humankind for Kant can be considered to be developing towards a healthy end: humans alone are able to move beyond a brutish state of existence to a more humane life. But humanity is faced with at least three different types of dissatisfactions related to this new freedom. Natural maturity precedes civil maturity. While a young person may possess the physical ability to procreate and raise a family, he or she does not usually have the “civil” qualifications for another ten years, according to Kant. This is alleviated as humans develop into ethical beings, but there will be an intermittent period of misery. Kant introduces the limitation of age as prohibiting humankind from achieving our moral potential. This is followed by the problem of human inequality and the imposition of a “civil right” as the solution to the problem.[10] Albeit flawed, Kant can now provide the distinctions that are necessary to make his approach coherent. The situation becomes even more complicated when the foundation of moral education, culture, is unable to fulfill its role in society. Culture, in a Kantian context, should be understood not as an aesthetic pursuit of the good, the true, and the beautiful, but as overarching basis for the moral improvement of all humans. Culture can provide for human freedom if it can transcend nature. Culture is incapable of changing the original needs of humankind, as its success is limited to the manufactured desires resulting from humankind’s use of reason. At the end of the day, we have some form of civil society, premised upon autonomous decision-making (avoiding the “heteronomy of the will”) that resembles our inordinate faith in reason as the guide to the moral life.

The “Conjectural Beginning of Human History”[1] is Kant’s attempt to recast the creation story of Genesis. The procreative act of Yahweh is cooperative in the sense heaven and earth are combined, as well as the essence of the Divine and humankind. According to Genesis 2:4, creation is the work of generations (toldoth); however, Kant’s creation is presented as a single, direct act; this account varies substantially from the complex series of events presented in the Book of Genesis which also contain a multiplicity of creative acts–and they are all the result of divine intervention. Kant prefers to change the circumstances of the origin of creation, making his essay a revolutionary enterprise. He inserts a “plan” whereby we can only improve out proverbial lot in life through individual efforts. On the other hand, the Biblical narrative allows us to possess most human facilities from the moment we enter the garden. As the result of the Fall, Kant decides to present humankind as moving from a beastlike state to a more civilized condition. The simple eidos of the account in Genesis takes the form of an ontological understanding of the universe; human existence becomes connected with the symbolization of creation. Kant’s creation narrative is a rejection of this aspect of the Biblical tradition, although as Stanley Rosen suggests, it provides Kant with a propitious opportunity to give his own version of the event.[2] The division Kant has chosen (Genesis 2-6) cannot be separated from a more substantial tradition. Kant has learned a tactic from the greatest manipulator of Genesis, Sir Robert Filmer, who used the initial chapter of Genesis to defend divine right monarchy. In due course, Locke, Sidney and others would refute this exploitation of the text, and deliver their own distortions of various sorts. Filmer and Kant commit the same error. The books Genesis to Joshua (Hexateuch), in their present form, constitute an immense, connected narrative. In either case, wherever one begins, the reader must keep in mind the narrative as a whole, and the contexts into which all the individual parts fit, and from which they are to be understood. Kant’s enterprise is based upon a denigration of the theophanic event, as it is traditionally understood. To dismiss the most important historical factors that are introduced as “intermediate causes,” Kant argues, is to “originate an historical account from conjectures alone.”[3] The result of such an approach is to present “a mere piece of fiction.”[4] God expresses Himself through His actions and these events are evidenced by the instances where we are told “God knew” of the situation in the garden, although in Kant’s account the garden is the result of a bountiful nature instead of a procreative action of the Divine. The Biblical account of Genesis presents God as always participating in human history and maintaining a desire to improve the lot of humanity, albeit God does not always take an active role in these activities. The revelatory acts Kant disparages in his “history” are the most prominent examples of the continuation of the Berith that can be found in Genesis and the Hebrew Bible. The precursor to a covenant is renewed and ratified at various intervals throughout the book; the mutual presence of God and humankind in the dialogue Kant has chosen to exegete is expanded into the mutual presence of God and his people. Kant and many contemporary biblical scholars argue that the structure and presentation of the creation idea are part of a cosmological world responding to the problems it was forced to encounter. Cosmological humans, from this perspective, did not possess the modern tools of explanation and were forced to depend on this vocabulary. The “story” presented in the first two chapters of Genesis is part of a larger canon of explanations of the universe. The Genesis story should be considered along with the Babylonian epic and other Memphite works as accounts that attempt to illuminate the creative act. Unfortunately, Kant and his epigones have failed to appreciate the reality of the event, and he is unsuccessful at reintroducing his version of a symbolic explication. Kant insinuates his solution to the “inevitable conflict between culture and the human species” when he satires Herder’s most ancient “document” of the human race by referring to it as the ancient “part” of human existence: contentment with Providence.”[5] What then follows comes into being through a process of nature, and the movement can generally be said to be from the natural to the moral. This more highly differentiated “justification of nature”[6] called providence diverges significantly from the Christian idea of providence as the foreknowledge of the Divine used in a way to protect His people on earth. The use of nature also takes on a more regimented meaning, implying it may be teleological in form. Providence must then be understood as the role of Kantian nature in history.[7]Although Kant is influenced by Rousseau, he rejects Rousseau’s philosophy of history. For Kant, human history is a transition directly related to an “analogy of nature.”[8] He argues that the original state of humankind cannot be denied, but he suggests it is not a state of crudeness because nature “has already taken mighty steps in the skillful use of its powers.”[9] Kant then proceeds to acknowledge the movement from natural instinct alone to a new state of power. Kant observed that the development of humankind as a moral lot could ameliorate the conflict between culture and species. Humankind for Kant can be considered to be developing towards a healthy end: humans alone are able to move beyond a brutish state of existence to a more humane life. But humanity is faced with at least three different types of dissatisfactions related to this new freedom. Natural maturity precedes civil maturity. While a young person may possess the physical ability to procreate and raise a family, he or she does not usually have the “civil” qualifications for another ten years, according to Kant. This is alleviated as humans develop into ethical beings, but there will be an intermittent period of misery. Kant introduces the limitation of age as prohibiting humankind from achieving our moral potential. This is followed by the problem of human inequality and the imposition of a “civil right” as the solution to the problem.[10] Albeit flawed, Kant can now provide the distinctions that are necessary to make his approach coherent. The situation becomes even more complicated when the foundation of moral education, culture, is unable to fulfill its role in society. Culture, in a Kantian context, should be understood not as an aesthetic pursuit of the good, the true, and the beautiful, but as overarching basis for the moral improvement of all humans. Culture can provide for human freedom if it can transcend nature. Culture is incapable of changing the original needs of humankind, as its success is limited to the manufactured desires resulting from humankind’s use of reason. At the end of the day, we have some form of civil society, premised upon autonomous decision-making (avoiding the “heteronomy of the will”) that resembles our inordinate faith in reason as the guide to the moral life.

Published on September 17, 2013 05:20

September 12, 2013

"Are conservatives still conservative?"Consider this and ...

"Are conservatives still conservative?"

Consider this and more in the McConnell Center's first lecture of Fall 2013. East Georgia State College's Lee Cheek will consider "The Conservative Mind at 60: Russell Kirk's Continuing Relevance in American Politics" on Sept. 10, 6-7 p.m., in Chao Auditorium (Ekstrom Library, University of Louisville). Russell Kirk's 'The Conservative Mind' at 60Tuesday, September 10 at 6:00pmEkstrom Library, University of Louisville in Louisville, Kentucky

Russell Kirk's 'The Conservative Mind' at 60Tuesday, September 10 at 6:00pmEkstrom Library, University of Louisville in Louisville, Kentucky

Consider this and more in the McConnell Center's first lecture of Fall 2013. East Georgia State College's Lee Cheek will consider "The Conservative Mind at 60: Russell Kirk's Continuing Relevance in American Politics" on Sept. 10, 6-7 p.m., in Chao Auditorium (Ekstrom Library, University of Louisville).

Russell Kirk's 'The Conservative Mind' at 60Tuesday, September 10 at 6:00pmEkstrom Library, University of Louisville in Louisville, Kentucky

Russell Kirk's 'The Conservative Mind' at 60Tuesday, September 10 at 6:00pmEkstrom Library, University of Louisville in Louisville, Kentucky

Published on September 12, 2013 14:15

August 21, 2013

June 6, 2013

Excellent, Nuanced Critique of Tocqueville

A Review of Lucien Jaume's Tocqueville: The Aristocratic Sources of Liberty (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2013).

While this profound, and elegantly written and translated work, will not appeal to all scholars of political thought, Jaume (Centre Recherche Politiques de Sciences Po) nevertheless provides many insights into the life and work of the great French student of American social and political life. Emphasizing the contribution of Democracy in America, the author suggests that the best interpretative model for understanding Tocqueville incorporates an appreciation for his historical context, arguing that Tocqueville should not be considered as our “contemporary” (p. 8); an acknowledgement of his attachment to French ideas; and a realization of the opaque nature of his critique (a “palette of meanings,” p. 9). Jaume proceeds to analyze Tocqueville as a political scientist, sociologist, moralist, and literary figure. As a political scientist, Tocqueville is an advocate of popular rule with an organic view of politics, and a defender of the diffusion of political authority and localism. Society begets political arrangements, and for Tocqueville, “society creates paths to its own ends” (p. 95). As a moralist, Tocqueville attempts to unite the “telos of democracy and the dignity of man” (p. 186). Finally, as a writer, Tocqueville is an “aristocratic moralist” (p. 326).

Published on June 06, 2013 15:41

March 31, 2013

From The Imaginative Conservative Alexander Hamilton...

From The Imaginative Conservative

Alexander Hamilton Stephens Reconsidered March 30, 2013 By Lee Cheek Leave a Comment H. Lee Cheek

by H. Lee Cheek, Jr., and Sean R. Busick Considering the large role he played in our nation’s past, Georgia’s Alexander Stephens deserves more than a footnote in our history. Limited by a popular and academic culture at the beginning of the 21st century that denigrates the past and places too much confidence in the present, the thoughtful student of Georgia politics and history should not be surprised that Alexander Stephens (February 11, 1812-March 4, 1883), Confederate Vice-President and American statesman, has often been neglected. To rescue Stephens from the dustbin of history it is helpful to reconsider the statesman’s life and work.

H. Lee Cheek

by H. Lee Cheek, Jr., and Sean R. Busick Considering the large role he played in our nation’s past, Georgia’s Alexander Stephens deserves more than a footnote in our history. Limited by a popular and academic culture at the beginning of the 21st century that denigrates the past and places too much confidence in the present, the thoughtful student of Georgia politics and history should not be surprised that Alexander Stephens (February 11, 1812-March 4, 1883), Confederate Vice-President and American statesman, has often been neglected. To rescue Stephens from the dustbin of history it is helpful to reconsider the statesman’s life and work.

Sean Busick Stephens was named for his grandfather, Alexander Stephens, a native of Scotland and veteran of the revolutionary war who settled in Georgia in the early 1790s. As the only child of the elder Alexander to remain in Georgia, Andrew Stephens was a successful farmer and educator. He married Margaret Grier in 1806. Within months of Stephens’ birth in 1812, his mother died as the result of pneumonia. His father quickly remarried Matilda Lindsey, a daughter of a local war hero. Matilda would exert great influence upon her stepson’s life, but the greatest inspiration to the young “Aleck” was his father. While not exhibiting any initial fondness for academic study, by 1824 Alexander was consumed with an interest in biblical narrative and history, and he began to read widely. In 1826, his mentor and teacher, Andrew Stephens, died from pneumonia; the stepmother soon died from the same affliction. Alexander was overcome by his grief, and he became disconsolate and fell into a state of melancholy. The siblings were divided, with Alexander and his brother Aaron moving in with their uncle Aaron Grier. While living with his uncle, Alexander was befriended by two Presbyterian ministers, Reverend Williams and Reverend Alexander Hamilton Webster, and these men would greatly aid his personal and intellectual development. Out of Alexander’s respect and devotion to Rev. Webster, he would eventually change his middle name to Hamilton. As the result of the encouragement offered by the clerics and others, the young Alexander entered Franklin College, which would become the University of Georgia. At Franklin, Stephens was guided in his studies by the eminent educationist, Reverend Moses Waddel, the brother-in-law and teacher of John C. Calhoun, and many of the emerging leaders of South Carolina. Waddel also played an important role in the spiritual development of the young man. Graduating first in his class at Franklin in 1832, he had distinguished himself as a scholar and capable debater. Stephens accepted a position as a tutor and began an independent study of the law. After passing the bar examination, Stephens was elected to the state legislature; he would spend six years in the state house and senate. It was becoming apparent that Stephens possessed the qualities necessary for political success. Initially refusing the request to run for the U. S. House, his political coalition merged with the Whig Party, and he decided to run for Congress in 1843. As a candidate, he defended the Whig Party’s positions on the national bank and tariffs. In a wave of Whig political success in Georgia, Stephens was elected to Congress, although sorrow would soon replace his joy. Within a brief period after his election, he received news that his brother Aaron had died. Stephens was again stricken with a profound sense of loss. After arriving in Washington to assume his seat, he was so sick that he was unable to attend legislative sessions. On February 9, 1844, in his first speech as a member of Congress, he challenged his own election. Stephens would become a Whig stalwart, campaigning for various Whig candidates and related causes, including Henry Clay’s unsuccessful presidential bid in 1844. The major issue before Congress was the annexation of Texas. In opposition to many southern congressmen who viewed the annexation of Texas as essential to the preservation of a political equilibrium that protected slavery, Stephens opposed expansion. Eventually, Stephens was forced to see the benefits of annexation for the South and the Whig Party, but he opposed the measure if based solely on the extension of slavery. Troubled by President Polk’s “bad management,” including greater tensions with England regarding Oregon, and the situation with Mexico, Stephens became an outspoken critic of the administration. Polk ordered General Zachary Taylor to the Rio Grande and a conflict transpired, prompting Polk to state that a war had been initiated. While Congress provided a declaration of war, Stephens agreed with Calhoun that the war could escalate into a greater conflict. In conjunction with other Whigs, Stephens tried to limit his support of the war and to prevent Congress from acquiring territory as the spoils of the contest. He introduced legislation aimed at limiting the aggrandizing policies of the Polk administration. By 1847 Stephens had become a central figure in the Young Indians Club, a group of congressmen who were supporting the presidential candidacy of General Zachary Taylor, who he believed shared the worldview of southern Whigs. After Taylor’s election, Stephens was forced to reconsider his support of Old Zack. Stephens found the doctrine of popular sovereignty more palatable because it was a countervailing force against the northern Whigs who wanted to admit California and New Mexico as free states. Working with his fellow Georgian and friend, Robert Toombs, they challenged their Whig colleagues to adopt resolutions forbidding Congress from ending the slave trade in the territories, but the effort failed. Within a short period of time, Stephens had moved from being a valued supporter of the administration to a critic and congressional opponent. He was forced to leave the Whig Party, but he maintained his legislative base of support in Georgia. In joining forces against the Whigs during a period of electoral realignment, he would assist in the formation of the Constitutional Union Party in Georgia. In the midst of the turmoil, Stephens eventually joined the Democratic Party; he supported the Compromise of 1850 and was instrumental in the adoption of the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854. Stephens thought the acceptance of Kansas-Nebraska was the “mission” of his life, and that “his cup of ambition was full.” After unsuccessfully supporting various measures that attempted to secure the position of the South, Stephens announced that he was retiring from Congress. He was weary and tired of confronting “restless, captious, and fault-finding people.” He did not support extremist measures offered by his colleagues from the South, but remained an advocate of states’ rights nevertheless. Even as southern radicals encouraged secession after the election of Lincoln in 1860, Stephens urged restraint, pleading with his follow Georgians to evince “good judgment,” and arguing that the ascendancy of Lincoln did not merit secession. In a celebrated exchange with the new president, he reminded Lincoln that “Independent, sovereign states” had formed the union and that these states could reassert their sovereignty. When Georgia convened a convention in January 1861, Stephens voted against secession, but when secession was approved by a vote of 166-130, he was part of the committee that drafted the secession ordinance. As the Confederacy evolved, Stephens was selected as a delegate and to many he appeared to be a good candidate for the vice presidency. He assumed an important role in the drafting of the Confederate Constitution and in other affairs, eventually accepting the vice presidency. Early in his tenure as Vice President, on March 21, 1861, he gave his politically damaging “Cornerstone” address in Savannah, where he defended slavery from a natural law perspective. President Jefferson Davis was greatly disturbed, as Stephens had shifted the basis of the political debate from states’ rights to slavery. Stephens was convinced that slavery was a necessity. The estrangement between Davis and Stephens increased, and by early 1862 the vice president was not intimately involved in the affairs of state. Accordingly, he returned to his home in Crawfordville. Pursuing actions he thought might assist in the denouement of the conflict, Stephens attempted several assignments, including a diplomatic sojourn to Washington. Returning to Richmond in December 1865, he introduced proposals to strengthen the Confederacy while presiding over the Senate. Following the conclusion of the war, Stephens faced arrest and imprisonment at Fort Warren, Massachusetts. After his release, he devoted the remainder of his life to composing A Constitutional View of the Late War Between the States, a two-volume defense of southern constitutionalism which appeared in 1868 and 1870. According to Stephens, the foremost theoretical and practical distillation of authority and liberty was found within the American political tradition. The original system was predicated upon preserving the states’ sphere of authority. For Stephens, as for most of the Founders as well, this original diffusion, buttressed by a prudent mode of popular rule, was the primary achievement of American politics. Though he is little remembered today, Stephens had a substantial impact on history and left us with one of the most important records of southern constitutional thought. Books mentioned in this essay may be found in The Imaginative Conservative

Bookstore

. Essays by Dr. Cheek may be found

here

. Essays by Dr. Busick may be found here.

H. Lee Cheek, Jr.,

Ph.D., Is a

Senior Contributor

at The Imaginative Conservative and Professor of Political Science and Religion at the University of North Georgia, and Senior Fellow of Alexander Hamilton Institute. His books include

Political Philosophy and Cultural Renewal

,

Calhoun and Popular Rule

,

Order and Legitimacy

, among others. Sean R. Busick is a

Senior Contributor

to The Imaginative Conservative and Associate Professor of History at Athens State University, and he is the author of

A Sober Desire for History: William Gilmore Simms as Historian

and other books. BibliographyBrumgardt, John R. “The Confederate Career of Alexander Stephens.” Civil War History, Volume 27, March 1981. Cheek, Jr., H. Lee. “Alexander Hamilton Stephens.” Encyclopedia of the American Civil War. New York: W. W. Norton Company, 2002. Rabun, James Z. “Alexander Stephens and the Confederacy.” Emory University Quarterly, Volume VI, October 1950. Schott, Thomas E. Alexander H. Stephens of Georgia: A Biography. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1988. Stephens, Alexander H. A Constitutional View of the Late War Between the States. Two Volumes. Philadelphia, 1868 and 1870. Reprinted, Sprinkle Publications, 1994.

Sean Busick Stephens was named for his grandfather, Alexander Stephens, a native of Scotland and veteran of the revolutionary war who settled in Georgia in the early 1790s. As the only child of the elder Alexander to remain in Georgia, Andrew Stephens was a successful farmer and educator. He married Margaret Grier in 1806. Within months of Stephens’ birth in 1812, his mother died as the result of pneumonia. His father quickly remarried Matilda Lindsey, a daughter of a local war hero. Matilda would exert great influence upon her stepson’s life, but the greatest inspiration to the young “Aleck” was his father. While not exhibiting any initial fondness for academic study, by 1824 Alexander was consumed with an interest in biblical narrative and history, and he began to read widely. In 1826, his mentor and teacher, Andrew Stephens, died from pneumonia; the stepmother soon died from the same affliction. Alexander was overcome by his grief, and he became disconsolate and fell into a state of melancholy. The siblings were divided, with Alexander and his brother Aaron moving in with their uncle Aaron Grier. While living with his uncle, Alexander was befriended by two Presbyterian ministers, Reverend Williams and Reverend Alexander Hamilton Webster, and these men would greatly aid his personal and intellectual development. Out of Alexander’s respect and devotion to Rev. Webster, he would eventually change his middle name to Hamilton. As the result of the encouragement offered by the clerics and others, the young Alexander entered Franklin College, which would become the University of Georgia. At Franklin, Stephens was guided in his studies by the eminent educationist, Reverend Moses Waddel, the brother-in-law and teacher of John C. Calhoun, and many of the emerging leaders of South Carolina. Waddel also played an important role in the spiritual development of the young man. Graduating first in his class at Franklin in 1832, he had distinguished himself as a scholar and capable debater. Stephens accepted a position as a tutor and began an independent study of the law. After passing the bar examination, Stephens was elected to the state legislature; he would spend six years in the state house and senate. It was becoming apparent that Stephens possessed the qualities necessary for political success. Initially refusing the request to run for the U. S. House, his political coalition merged with the Whig Party, and he decided to run for Congress in 1843. As a candidate, he defended the Whig Party’s positions on the national bank and tariffs. In a wave of Whig political success in Georgia, Stephens was elected to Congress, although sorrow would soon replace his joy. Within a brief period after his election, he received news that his brother Aaron had died. Stephens was again stricken with a profound sense of loss. After arriving in Washington to assume his seat, he was so sick that he was unable to attend legislative sessions. On February 9, 1844, in his first speech as a member of Congress, he challenged his own election. Stephens would become a Whig stalwart, campaigning for various Whig candidates and related causes, including Henry Clay’s unsuccessful presidential bid in 1844. The major issue before Congress was the annexation of Texas. In opposition to many southern congressmen who viewed the annexation of Texas as essential to the preservation of a political equilibrium that protected slavery, Stephens opposed expansion. Eventually, Stephens was forced to see the benefits of annexation for the South and the Whig Party, but he opposed the measure if based solely on the extension of slavery. Troubled by President Polk’s “bad management,” including greater tensions with England regarding Oregon, and the situation with Mexico, Stephens became an outspoken critic of the administration. Polk ordered General Zachary Taylor to the Rio Grande and a conflict transpired, prompting Polk to state that a war had been initiated. While Congress provided a declaration of war, Stephens agreed with Calhoun that the war could escalate into a greater conflict. In conjunction with other Whigs, Stephens tried to limit his support of the war and to prevent Congress from acquiring territory as the spoils of the contest. He introduced legislation aimed at limiting the aggrandizing policies of the Polk administration. By 1847 Stephens had become a central figure in the Young Indians Club, a group of congressmen who were supporting the presidential candidacy of General Zachary Taylor, who he believed shared the worldview of southern Whigs. After Taylor’s election, Stephens was forced to reconsider his support of Old Zack. Stephens found the doctrine of popular sovereignty more palatable because it was a countervailing force against the northern Whigs who wanted to admit California and New Mexico as free states. Working with his fellow Georgian and friend, Robert Toombs, they challenged their Whig colleagues to adopt resolutions forbidding Congress from ending the slave trade in the territories, but the effort failed. Within a short period of time, Stephens had moved from being a valued supporter of the administration to a critic and congressional opponent. He was forced to leave the Whig Party, but he maintained his legislative base of support in Georgia. In joining forces against the Whigs during a period of electoral realignment, he would assist in the formation of the Constitutional Union Party in Georgia. In the midst of the turmoil, Stephens eventually joined the Democratic Party; he supported the Compromise of 1850 and was instrumental in the adoption of the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854. Stephens thought the acceptance of Kansas-Nebraska was the “mission” of his life, and that “his cup of ambition was full.” After unsuccessfully supporting various measures that attempted to secure the position of the South, Stephens announced that he was retiring from Congress. He was weary and tired of confronting “restless, captious, and fault-finding people.” He did not support extremist measures offered by his colleagues from the South, but remained an advocate of states’ rights nevertheless. Even as southern radicals encouraged secession after the election of Lincoln in 1860, Stephens urged restraint, pleading with his follow Georgians to evince “good judgment,” and arguing that the ascendancy of Lincoln did not merit secession. In a celebrated exchange with the new president, he reminded Lincoln that “Independent, sovereign states” had formed the union and that these states could reassert their sovereignty. When Georgia convened a convention in January 1861, Stephens voted against secession, but when secession was approved by a vote of 166-130, he was part of the committee that drafted the secession ordinance. As the Confederacy evolved, Stephens was selected as a delegate and to many he appeared to be a good candidate for the vice presidency. He assumed an important role in the drafting of the Confederate Constitution and in other affairs, eventually accepting the vice presidency. Early in his tenure as Vice President, on March 21, 1861, he gave his politically damaging “Cornerstone” address in Savannah, where he defended slavery from a natural law perspective. President Jefferson Davis was greatly disturbed, as Stephens had shifted the basis of the political debate from states’ rights to slavery. Stephens was convinced that slavery was a necessity. The estrangement between Davis and Stephens increased, and by early 1862 the vice president was not intimately involved in the affairs of state. Accordingly, he returned to his home in Crawfordville. Pursuing actions he thought might assist in the denouement of the conflict, Stephens attempted several assignments, including a diplomatic sojourn to Washington. Returning to Richmond in December 1865, he introduced proposals to strengthen the Confederacy while presiding over the Senate. Following the conclusion of the war, Stephens faced arrest and imprisonment at Fort Warren, Massachusetts. After his release, he devoted the remainder of his life to composing A Constitutional View of the Late War Between the States, a two-volume defense of southern constitutionalism which appeared in 1868 and 1870. According to Stephens, the foremost theoretical and practical distillation of authority and liberty was found within the American political tradition. The original system was predicated upon preserving the states’ sphere of authority. For Stephens, as for most of the Founders as well, this original diffusion, buttressed by a prudent mode of popular rule, was the primary achievement of American politics. Though he is little remembered today, Stephens had a substantial impact on history and left us with one of the most important records of southern constitutional thought. Books mentioned in this essay may be found in The Imaginative Conservative

Bookstore

. Essays by Dr. Cheek may be found

here

. Essays by Dr. Busick may be found here.

H. Lee Cheek, Jr.,

Ph.D., Is a

Senior Contributor

at The Imaginative Conservative and Professor of Political Science and Religion at the University of North Georgia, and Senior Fellow of Alexander Hamilton Institute. His books include

Political Philosophy and Cultural Renewal

,

Calhoun and Popular Rule

,

Order and Legitimacy

, among others. Sean R. Busick is a

Senior Contributor

to The Imaginative Conservative and Associate Professor of History at Athens State University, and he is the author of

A Sober Desire for History: William Gilmore Simms as Historian

and other books. BibliographyBrumgardt, John R. “The Confederate Career of Alexander Stephens.” Civil War History, Volume 27, March 1981. Cheek, Jr., H. Lee. “Alexander Hamilton Stephens.” Encyclopedia of the American Civil War. New York: W. W. Norton Company, 2002. Rabun, James Z. “Alexander Stephens and the Confederacy.” Emory University Quarterly, Volume VI, October 1950. Schott, Thomas E. Alexander H. Stephens of Georgia: A Biography. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1988. Stephens, Alexander H. A Constitutional View of the Late War Between the States. Two Volumes. Philadelphia, 1868 and 1870. Reprinted, Sprinkle Publications, 1994.

Alexander Hamilton Stephens Reconsidered March 30, 2013 By Lee Cheek Leave a Comment

H. Lee Cheek

by H. Lee Cheek, Jr., and Sean R. Busick Considering the large role he played in our nation’s past, Georgia’s Alexander Stephens deserves more than a footnote in our history. Limited by a popular and academic culture at the beginning of the 21st century that denigrates the past and places too much confidence in the present, the thoughtful student of Georgia politics and history should not be surprised that Alexander Stephens (February 11, 1812-March 4, 1883), Confederate Vice-President and American statesman, has often been neglected. To rescue Stephens from the dustbin of history it is helpful to reconsider the statesman’s life and work.

H. Lee Cheek

by H. Lee Cheek, Jr., and Sean R. Busick Considering the large role he played in our nation’s past, Georgia’s Alexander Stephens deserves more than a footnote in our history. Limited by a popular and academic culture at the beginning of the 21st century that denigrates the past and places too much confidence in the present, the thoughtful student of Georgia politics and history should not be surprised that Alexander Stephens (February 11, 1812-March 4, 1883), Confederate Vice-President and American statesman, has often been neglected. To rescue Stephens from the dustbin of history it is helpful to reconsider the statesman’s life and work.