Jordan B. Cooper's Blog, page 48

November 20, 2014

Christian Dogmatics Lesson 2: The Aim of Theology

In this second session of the Christian Dogmatics course, we discussed the aims of theology, and the relationship of theology to science, philosophy, and ethics.

Here is the video

The outline for this class can be found here: Christian Doctrine Class 2 Outline

November 19, 2014

Resources from Dr. Joel Biermann on the Two Kinds of Righteousness

This is a compilation of many of the available resources from Joel Biermann regarding his teaching on the two kinds of righteousness.

Just and Sinner Programs

Preaching the Two Kinds of Righteousness

Other interviews

A Case for Character (and Potlucks!)- Boars in the Vineyard

Videos from Lutheran Doctrine Course

Two Kinds of Righteousness Part 1 Part 2 Part 3

Uses of the Law Part 1 Part 2 Part 3

A Case for Character Videos

The book can also be purchased here.

Two Raspy Sermons on the End of the World

My last two sermons have focused on the parable of the Wise and Foolish Virgins and the parable of the Talents respectively (both in Matt 25). I’ve been congested a while, and preached both with the aid of Mucinex and water laced with an herbal remedy. My voice is considerably rougher in the second sermon. Think of it as an Apocalyptic special effect.

22nd Sunday after Pentecost (Amos 5:18–24, 1 Thessalonians 4:13–18, Matthew 25:1–13):

23rd Sunday after Pentecost (Zephaniah 1:7–16, 1 Thessalonians 5:1–11, Matthew 25:14–30)

Egad, that’s my longest sermon ever. The cold must have slowed my delivery or something.

November 18, 2014

Christ Dwells Within Us, And We Should Be Talking About It.

I often hear Lutherans say things like: “It’s not about Christ in us, but Christ for us.” The “Christ in us” language belongs to pop evangelicalism and the Eastern Orthodox. For Lutherans, Christ in us is a reality…but we shouldn’t really talk about it. To do so would be to adopt an evangelical or Eastern view of the Christian life. If we focus on the indwelling Christ, then we will be pointed inward for assurance, and for justification. When that happens, we are no longer Lutherans!

This kind of thinking has, I think, been very damaging to the Lutheran church as we have lost the traditional language of the unione mystica (mystical union). Yes, we probably confess the mystical union, but do we ever talk about it? Have you ever heard your pastor preach on it? Has your favorite blog, author, or podcast ever spoken on it? And I don’t mean just in passing, but actually dealt with it positively and extensively. Our forefathers were not afraid to speak of Christ in us. C.F.W. Walther preached on the topic often (see his sermon “On the Gracious Dwelling of God in the Hearts of Men,” in From our Master’s Table, 76), and Johann Gerhard meditates on it extensively in his Sacred Meditations.

There is a fear of speaking about the indwelling Christ because we don’t want to give believers the idea that assurance must be found within us, rather than in the objective means of grace. When assurance or justification is placed inward, then we really miss the mark, and we are really no longer Lutherans at that point (I have spoken against these views of assurance here). That problem shows itself in medieval mysticism, puritanism, and especially in some later strands of pietism.

So what should we do then? If we can’t point people inward for assurance, then how do we speak about the mystical union? Should we ignore it? Should we just tell people not to worry about it? That solution is, I think, a common one, but in doing so we are ignoring some really important passages of Scripture.

“I have been crucified with Christ; and it is no longer I who live, but Christ lives in me; and the life which I now live in the flesh I live by faith in the Son of God, who loved me and gave Himself up for me.” (Gal. 2:20)

“so that Christ may dwell in your hearts through faith; and that you, being rooted and grounded in love, may be able to comprehend with all the saints what is the breadth and length and height and depth, and to know the love of Christ which surpasses knowledge, that you may be filled up to all the fullness of God.” (Eph. 3:17-19)

“If Christ is in you, though the body is dead because of sin, yet the spirit is alive because of righteousness.” (Rom. 8:10)

“My children, with whom I am again in labor until Christ is formed in you.” (Gal. 4:19)

“to whom God willed to make known what is the riches of the glory of this mystery among the Gentiles, which is Christ in you, the hope of glory.” (Col. 1:27)

I think the best way to deal with both of these prominent Biblical themes, Christ for you and Christ in you, is within the context of the two kinds of righteousness. In one’s life coram Deo, the sole concern is Christ as he is for you. When dealing with the passive righteousness of faith, and one’s status before God, we must always look to the objective means of grace given to us for assurance. We look to Christ’s objective life, death, and resurrection from the dead. It is here alone that the Christian finds assurance of forgiveness, life, and righteousness. With regard to this question, we cannot look inward at any works, obedience, or renewal within us. Instead, we look solely to Christ’s alien righteousness.

However, one’s life coram mundo is not only about Christ for us. Instead, we live in this world in view of Christ in us. Our concern in our vocations is not merely the passive righteousness of faith, but the active righteousness of renewal that the Spirit is working within us. Here, in this realm, life is all about Christ as he dwells within us, helping us to love and serve one another. It is in this realm that the third use of the law functions in order to guide us in this life, that we might be obedient to God and serve our neighbor. And this is only possible because the Holy Trinity is dwelling within us, changing us, conforming us to the image of Christ, and thus giving us the ability to serve others.

As Lutherans, we must be bold to speak about all Biblical truths. We need not be afraid to talk about Christ dwelling within our hearts. Rather, we simply must be careful about the context in which we do this. If the question is assurance, its all about Christ for us. If the question is one’s life in the world, its all about Christ in us.

November 17, 2014

The Question That Should End All Debate About the Third Use of the Law

Luther: “What do we older folks live for if not for the care of the young, to teach and train them?” — Martin Luther (Martin Luther, the Estate of Marriage)

“…the Law of God is useful… to the end that… when [men] have been born anew by the Spirit of God…they live and walk in the law” — FC VI: 1

Here it is, a practical question Americanized Christians indoctrinated into toxic freedom might not immediately get, but most all little kids can probably make sense of:

Just because my children must sometimes be coerced to attend worship services, does that necessarily mean they are not Christians?

(perhaps check out the previous post I mentioned: “Come to me and I will give you rest.” Law or gospel?)

If you answer “no” to that question, you can come to grips with what the Lutheran Confessors were trying to say as regards the “third use of the law”, namely this:

It’s all about Christian’s Spirit-led and default inclination being to coerce and drag old Adam – some other Christian’s or our own – into the presence of God’s means of grace and beyond… i.e. into the straight paths that make life safe and good for straying sheep.

It’s that easy. Amazing how Satan can pull the wool over our eyes!

But what about the law’s accusation? Well, that is not what FC, article VI is about… but let’s address the issue head-on: we can definitely say that the law always kills old Adam. Further – we can say that the law does not have the power to produce God-pleasing works – with a qualification. The qualification is that “God-pleasing works” are defined as those that are motivated primarily by the Gospel in the Christian and are not done as a result of external coercion – like when I make my kids attend worship or sit for family devotions when they don’t want to. On the other hand, so long as the coerced believer has faith – no matter how small, the Gospel covers all their sin anyway for Christ’s sake, making these works “God-pleasing” in a sense as well – they are not externally bad works after all.

If you’d like, you can stop reading now. That’s the main point. If you would like more theological-egg-head stuff, read on….

In the Solid Declaration of the Formula of Concord (VI:9) it recommends for our reflection a Luther sermon regarding the third use of the law: “as Dr. Luther has fully explained this at greater length in the Summer Part of the Church Postil, on the Epistle for the Nineteenth Sunday after Trinity” (Pastor Mark Surburg helpfully explores the implications of this here). The Formula of Concord does not point us to Martin Luther’s Antinomian Disputations at this point, but this simply goes to but this simply goes to show that sometimes we might not understand something in front of us quite the way we should without looking at something else that goes into more detail about the matter.*

Family devotions with Dr. Luther: “The inexperienced and perverse youth need to be restrained and trained by the iron bars of ceremonies lest their unchecked ardor rush headlong into vice after vice… they are rather to be taught that they have been so imprisoned in ceremonies, not that they should be made righteous or gain great merit by them, but that they might thus be kept from doing evil and might more easily be instructed to the righteousness of faith.“

In a previous post of which this is a follow-up, I critiqued a quote by Jack Kilcrease, posted by Pastor Matt Richards, about the third use of the law (read his whole paper here). Let me go into more detail specifically about what I am saying there. Kilcrease’s words do not really do justice to the fully-orbed reality of the situation being addressed in FC VI – the text is saying things that he is not saying.

As Kilcrease notes, the first use of the law – its “political use” – is not meant to instruct or discipline Christians. The third use of the law, on the other hand, is. Again, my point here is that the third use of the law is not primarily concerned to be talking about the matter of the law’s accusation** (of the non-Christian or Christian), but it is talking about the law being used with Christians specifically*** – for instruction and discipline – with the result being obedience.

I hope the following goes a long way in making my previous post more clear. When the law is used with Christians with the result being obedience, there are a few things that may be happening:

Christians obey due to authorities who need to use coercion (parents, teachers, pastors, neighbors, etc) because they are letting their old man get a hold of their new man (hence we read later: “But *the believer* without any coercion and with a willing spirit, *in so far as he is reborn*, does what no threat of the law could ever have wrung from him”). What this means is that the believer, in so far as he is not reborn, does good only when it is wrung out of him – maybe even by using explicitly stated rewards and punishments. Again though, these coerced works are not “works of the law” per se, because they are still done by believers, and the blood of Christ covers these forced works, making them pleasing in the eyes of God.

Obviously, this is less than ideal. Here is something that is much better:

Christians obey willingly without coercion, due to their putting their old man in its place – by their new man (not Christ, but the new nature that wills – “not my will…” – to cooperate with Christ’s Spirit) who is eager to do so, and spontaneously does so more or less consciously (in other words, they cheerfully and joyfully make the decision, in cooperation with Christ’s Spirit, to do something in the midst of a necessary fight vs. their old man, utilizing even “teaching, admonition, force, threatening of the Law,….the club of punishments[,] and troubles” themselves against their old man – their old nature). Regarding the “new man” in SD II a concrete anthropological location is indicated in the Christian for the renewed delight in God’s holy law – this is his “concreated righteousness”.

Again, FC VI, the third use of the law, is not really about its accusation and corresponding repentance. It is about the end result of obedience. Now, better yet:

Christians obey willingly without coercion either more or less unconsciously (in other words, they simply do something without needing to fight much vs. their old man). Ideally, we do these good works more and more spontaneously, as Old Adam’s strength dissipates – while never fully disappearing in this life. Here, again, we think about Luther’s famous words introducing the book of Romans….

“When [Christ, the fulfiller of the law] is present, the law loses its power. It cannot administer wrath because Christ has freed us from it. Then he brings the Holy Spirit to those who believe in him that they might delight in the law of the Lord, according to the first psalm (Ps. 1:2). In this way their souls are recreated with [the Law] in view and this Spirit gives them the will that they might do it. In the future life, however, they will have the will to do the law not only in Spirit, but also in flesh, which, as long as it lives here, strives against this delight. To render the law delightful, undefiled is therefore the office of Christ, the fulfiller of the law, whose glory and handiwork announce the heavens and the firmament, the apostles and their successors (Ps. 19:1, cf. Rom. 10:18).” See also his exposition of Ps. 1:2 in AE 14:294f.

Here we must say this: when the Formula says that if we were free from sin we would obey “just as the sun of itself, without any [foreign] impulse, completes its ordinary course”, this illustration does not necessarily mean that there will not be some real, conscious, struggle of wills in the Christian to obey as regards one’s own person. This can in fact describe both the second and third kind of scenarios (and of course it also does not seek to make the Christian out to be some kind of automaton or inert tool of sorts [see this recent post from Pastor Matt Richards, which seems like this to me] for the very voluntary volitional obedience of the angels is also mentioned (VI:6)).To re-iterate: the article on the third use of the law is not really about the accusation of the law – that was covered earlier in the FC – but it is rather about the new obedience of the Christian as regards God’s law.

In other words, for some believers – for those whose new man is strong – this use of the law certainly is “more harmless than any other use of the law”. It *can*, contra Kilcrease, be “rightly be characterized as a pleasant or non-threatening form of the law” and even “friendly”.

Why? Because while the law always accuses, they, ever conscious of the Gospel and its high call, know that they are forgiven in Christ (see Ap. IV, 167) and are, correspondingly, eager to do good.****

So, as Luther says, the Holy Spirit renders the Law enjoyable and gentle to the justified and we can even say that, to the extent that a believer is “actively” righteous, the law’s accusatory office has ceased.

Dr. Kilcrease also said: “Therefore, when the Formula of Concord posits a third use of the law, it is not supplementing a weak connection between justification and sanctification by trying to inculcate obedience to the law”. In light of what has been written above, I now think that this statement is highly questionable as well.

In other words, as Pastor Holger Sonntag explained to me, “SD VI is taking a deep anthropological look at AC VI, which commends itself, given that that anthropology needed clarifying/reaffirming against the new Manichaeans in SD I.”

Again, Pastor Sonntag’s words:

“In other words, FC VI considers the law not as that which condemns the sinner to hell, but as “the definite rule” which, by means of its fierce threats (and sweet promises!), coerces the old man in the believer into what can only be an unwilling obedience and hence into an unwilling cooperation with the Holy Spirit and the reborn part of the believer, the new man in us, who willingly does what the one law of God teaches him as a “definite rule according to which he should pattern and regulate his entire life”.

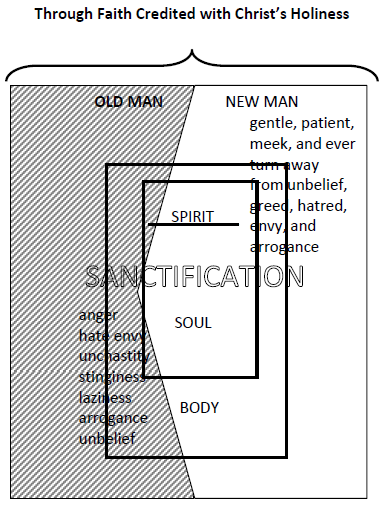

Finally, what all of this highlights is a simple Scriptural truth we should all recognize: it is the more highly sanctified men, not those who need it the most, who are eager to hear words of both direction and correction. Further as regards the Christian’s sanctification, this is important to add: while there is growth in piety and sanctification, it’s not really a linear progression, meaning: we may feel strong one day and weak the next. Nevertheless, over the whole of the Christian life, the following picture shows how it should look – even if we ourselves, ever aware of our sin, do not see this progress.

VI:5 – “nor must [the law] vex the regenerate with its coercion, because they have pleasure in God’s Law after the inner man.” Picture from paper here.

FIN

Notes:

*In like fashion, in the “worship wars” look at how people treat the section on adiaphora in the FC. They read the words, but totally miss the clear implications of the words – what they are really getting at. However, if they read more of Luther on these issues, they might be able to discern – should be able to discern – what the words in the Formula are really getting at. I plan on doing some posts on this in the future: “How an improper understanding of sanctification lies at the root of the worship wars”.

Here, SD, Rule and Norm 9 is noted: “The pure churches and schools have everywhere recognized these publicly and generally accepted documents [the "Lutheran" confessions adopted in the 1530s] as the sum and pattern of the doctrine which Dr. Luther of blessed memory clearly set forth in his writings on the basis of God’s Word and conclusively established against the papacy and other sects. We also wish to be regarded as appealing to further extensive statements in his doctrinal and polemical writings, but in the necessary and Christian terms and manner in which he himself refers to them in the Preface to the Latin edition of his collected works.”

**Note the text in the Epitome of article VI, it does not say: “(3) after they are reborn, and while the flesh still inheres in them, to lead them to a knowledge of their sin, so they don’t forget Jesus and become Pharisees.”

***Note from SD IV: “We should often, with all diligence and earnestness, repeat and impress upon Christians who have been justified by faith these true, immutable, and divine threats and earnest punishments and admonitions.” Also from Epitome IV:

3] 2. Afterwards a schism arose also between some theologians with respect to the two words necessary and free, since the one side contended that the word necessary should not be employed concerning the new obedience, which, they say, does not flow from necessity and coercion, but from a voluntary spirit. The other side insisted on the word necessary, because, they say, this obedience is not at our option, but regenerate men are obliged to render this obedience.

4] From this disputation concerning the terms a controversy afterwards occurred concerning the subject itself; for the one side contended that among Christians the Law should not be urged at all, but men should be exhorted to good works from the Holy Gospel alone; the other side contradicted this.”

****From Luther’s Antinomian Disputations, we learn that under the accusatory law insofar as they are sinners, Christians are also “without the law” because Christ’s fulfillment of the law is imputed to them and insofar as they battle sin in their lives in the power of the Holy Spirit (pp. 16-17, Sonntag, God’s Last Word)

November 14, 2014

The Tyranny of Fruit Checking: A Lecture from the PCR Conference

The lecture I gave titled “The Tyranny of Fruit Checking” at the Pirate Christian Radio Conference in August has been released. It is a critique of approaches to assurance based upon one’s good works as found in Paul Washer, Tim Conway, and some other contemporary Calvinist baptist preachers.

Theosis is Glorification

Oposition to the doctrine of theosis among Lutherans seems to be rooted in the fear that it’s an alternate explanation for how we are saved, that it’s somehow in competition with justification through faith alone. And the way it’s usually presented by the Eastern Orthodox, it is, but that’s deeply backwards. Divinization is not a present reality that wins us future glory. Divinization is the future glory. It’s the end product, it’s the telos. Theosis is glorification.

I have never seen a Lutheran deny glorification. I don’t think I’ve seen a Christian of any stripe deny it, though I haven’t heard it talked about all that much either. The Resurrection of the righteous involves an ontological change—a change in human nature. “we know that when he appears we shall be like him, because we shall see him as he is” (I Jn. 3:2b). At present we are mortal, corruptible, and sinful. In the life of the world to come we will be immortal, incorruptible, and sinless. We will in fact be unable to sin. “And so shall we ever be with the Lord” (I Thess. 4:17b)—a promise that could not hold if a second Fall were conceivable. In the heavenly state, the cycle of sin and repentance will be broken. Sin will be no more possible than death. “But nothing unclean will ever enter , nor anyone who does what is detestable or false” (Rev. 21:27a).

St. Paul lays it out for us in Romans 8:29-30, complete with an ordo salutis (order of salvation):

For those whom he foreknew he also predestined to be conformed to the image of his Son, in order that he might be the firstborn among many brothers. And those whom he predestined he also called, and those whom he called he also justified, and those whom he justified he also glorified.

From this we learn two things crucial to the point I am making. First, we are not simply predestined to eternal life and eternal happiness, but eternal perfect Christlikeness. The end of the Christian life is “to be conformed to the image of His Son.” Second, the last step in the ordo is to be “glorified.” So it follows that glorification is the full measure, the completion, of our conformation to Christ. What does it mean to be glorified? It means to be made definitively, perfectly like Christ.

Christ is God. This is theosis. Notice, we do not become Christ; we become images of Christ. Christ is “the Image of the Invisible God” (Col. 1:15a), and we are in turn His images. “Just as we have borne the image of the man of dust, we shall also bear the image of the man of heaven” (I Cor. 15:49). We do not lose our human identity, but we do transcend the limitations proper to human nature. “For the trumpet will sound, and the dead will be raised imperishable, and we shall be changed. For this perishable body must put on the imperishable, and this mortal body must put on immortality” (I Cor. 15:52b-53). I think it is clear that this is what St. Peter means by becom[ing] partakers of the divine nature” (2 Pet. 1:4). It is, at any rate, what the Church Fathers meant when they spoke of divinization.

Theosis is glorification. It’s what happens at the Resurrection, the Beatific Vision. I am genuinely curious to know if any of the Lutherans I have been recently debating, or anyone else who opposes the doctrine of theosis, can object to this equation.

So what about the present? Is it proper to speak of divinization as a present reality, and not just a future one? Yes it is, because we have received the Holy Spirit. The first 28 verses of Romans 8, leading up to the ordo I quoted above, are all about the Holy Spirit and His work in the Christian, and one thing is clear: since we have the Spirit, we already have the life of the world to come—not full-grown yet, but in embryo:

But if Christ is in you, although the body is dead because of sin, the Spirit is life because of righteousness. If the Spirit of him who raised Jesus from the dead dwells in you, he who raised Christ Jesus from the dead will also give life to your mortal bodies through his Spirit who dwells in you. (v. 11)

We will be raised on the Last Day through the very Spirit that dwells in us right now. That’s why the Spirit is called “the down-payment of our inheritance” in Eph. 1:14. He’s like a cash advance, except that the currency is life and holiness, because He is the Holy Spirit, “the Lord, the Giver of Life” (Nicene Creed). What we have in Him is exactly what we’ll have in the Resurrection; we just have not been perfectly conformed to it yet. The difference between the holiness and life of the Church Militant, and the holiness and life of the Church Triumphant—that is to say, between sanctification and glorification—is not qualitative, but quantitative. The one is a process, the other is perfection. That’s why St. Paul left “sanctification” out of his ordo in Rom. 8: because “glorification” includes it, the way the full includes the partial. And no, this doesn’t mean that you work your way up the ladder until you get to God, as in Papist synergy, because the process ends at death. There’s no Purgatory to continue it. According to Scripture, the perfection is granted instantaneously, when we rise with Christ. The vast gap between His perfect image and your actual status at death will be obliterated “in a moment, in the twinkling of an eye, at the last trumpet” (I Cor. 15:52a).

This is why justification through faith alone is the paramount doctrine for this life, because “what we will be has not yet appeared,” even though it’s true that “we are God’s children now” (I Jn. 3:2). So we have to take it on faith that we are, and that it will—not because of our own merits, present or future, but only through the righteousness of Christ, received through faith.

If any of this stuff re: the relationships among justification, sanctification, and glorification sounds strange or non-Lutheran, it shouldn’t. This is what the Formula of Concord teaches.

In like manner also renewal and sanctification, although it is also a benefit of the Mediator, Christ, and a work of the Holy Ghost, does not belong in the article or affair of justification before God, but follows the same since, on account of our corrupt flesh, it is not entirely perfect and complete in this life, (SD III.28)

It is also correctly said that believers who in Christ through faith have been justified, have in this life first the imputed righteousness of faith, and then also the incipient righteousness of the new obedience or of good works. But these two must not be mingled with one another or be both injected at the same time into the article of justification by faith before God. For since this incipient righteousness or renewal in us is incomplete and impure in this life because of the flesh, the person cannot stand with and by it before God’s tribunal, but before God’s tribunal only the righteousness of the obedience, suffering, and death of Christ, which is imputed to faith, can stand, so that only for the sake of this obedience is the person (even after his renewal, when he has already many good works and lives the best life) pleasing and acceptable to God, and is received into adoption and heirship of eternal life. (SD III.32)

So here is my conclusion.

1) Theosis is glorification.

2) Sanctification is incipient glorification.

3) Therefore sanctification is incipient theosis.

Pastor Sonntag’s Extremely Helpful Comments on the Brothers of John the Steadfast Blog

Martin Luther’s Antinomian Disputations, translated by Pastor Holger Sonntag. See here to order.

[Note: this post was accidently published earlier today under Trent Demarest's name by me, Nathan Rinne.]

Again, not long ago at the Brothers of John the Steadfast blog, a discussion was started which came largely to focus on Pastor Jordan Cooper’s writing a book about theosis. One of the more helpful, clarifying, and enlightening comments came from Pastor Holger Sonntag, the translator of Martin Luther’s Antinomian Disputations available through Lutheran Press.

Here is how Pastor Sonntag responded to T.R. Halvorson’s article. The boldface emphases in the post are Pastor Sonntag’s:

+ + +

I’ll provide a running commentary to your article, if you don’t mind.

Ok, I take this to be your core proposition:

Despite what seems to be a dizzying array of ideas and movements that undermine, erode, or outright displace justification, really, there is a single thread running through them: theosis. When we see this single thread, we can be nimble in defending the flock.

Then you lay out that you want to track this erosion / displacement of justification (I assume you mean: “justification by grace through faith in Christ alone”—there’s also “justification by good works,” see Rome etc.; you clearly don’t want that—which is great!)

The problem I see at this point, and the messy discussion really has borne this out, that you identify “theosis” right off the bat with “undermine, erode, or downright displace justification.” Some folks took issue with that (note to self: “theosis” can have different meanings), and you’ve been talking about “theosis” ever since—instead of what you were really aiming at, which was discussing various attempts to marginalize and replace the biblical doctrine of justification by grace through faith in Christ alone.

But, only hindsight is 20-20. And, I think, people of good will should be able to reset their heads to say: ah, ok, maybe this wasn’t set up so well, but the biblical doctrine of justification should be a concern for all of us—and certainly pastors should be vigilant in this area, as our eternal lives are at stake. So, let’s talk about that.

Because that’s really what then ALSO happened: how is our growing sanctification properly understood (taught/preached) in its relation to the doctrine of justification? But the other issues, like a mighty avalanche, always kept intruding back into this important discussion. So the differences that have been voiced—at times quite harshly—were they about terminology? Were they about substance? I’m inclined to say “yes” to both, but because the terminology discussion generated so much heat, and not very much light, we’ve perhaps not advanced as far as we could have in the matter of substance, by God’s grace.

Anyway, as to your substantial points, the various objectionable forms in which you observe “theosis” around us and among us.

First, the EO model. I let others with more knowledge about EO theology speak to it in greater detail, specifically as to whether EOs really believe in a bloodless atonement (by incarnation only). If they did, however, they are certainly wrong.

I add, though, that also for the Lutherans the incarnation is amazing in that it elevates our human nature to divine glory at the right hand of God because at that point in time the personal union is formed (cf. SD VIII, 13). Are we saved by this exaltation in the virgin womb of Mary? No. But I’d say it sure is great comfort to know that God, in the very divine-human person of Christ, has brought about such an indestructible embodiment of the Gospel promises made to wretches like us.

That said, a key text in the discussion seems to be 2 Peter 1:4. First of all, let’s admit: it doesn’t mention “theosis” or “divinization” by name. Since those terms are causing some confusion among us, we should stop our EO interlocutors right there: “Wait. Let’s first look at what it does say. What it does say is that we become partakers of the divine nature by means of what?—our good works? Our sanctified life? No, by means of God’s promises!”

Safe to say, where God’s word speaks about this type of promises, it has faith, not love, in view! So, a great Lutheran text, thank you very much.

This, I submit, is really the key question here: how do we become partakers of the divine nature? By faith alone? By love alone? By faith and love to varying degrees? This is how we can use the proper doctrine of justification as a tool to avoid falling into legalism in other doctrines.

Luther’s own interpretation of the text bears out that the text is really a great text of the Bible and for (in favor of) the Lutheran faith (too bad we don’t talk about it more often), AE 30:155:

Through the power of faith, [the apostle Peter] says, we partake of and have association or communion with the divine nature. This is a verse without a parallel in the New and the Old Testament, even though unbelievers regard it as a trivial matter that we partake of the divine nature itself. But what is the divine nature? It is eternal truth, righteousness, wisdom, everlasting life, peace, joy, happiness, and whatever can be called good. Now he who becomes a partaker of the divine nature receives all this, so that he lives eternally and has everlasting peace, joy, and happiness, and is pure, clean, righteous, and almighty against the devil, sin, and death. Therefore this is what Peter wants to say: Just as God cannot be deprived of being eternal life and eternal truth, so you cannot be deprived of this. If anything is done to you, it must be done to God; for he who wants to oppress a Christian must oppress God.

All this is included in the term “divine nature,” and St. Peter has used it for the very purpose of including all this. It is surely something great when one believes it. But, as I have stated above, with all these instructions he does not lay a foundation for faith but emphasizes what great and rich blessings we receive through faith. For this reason he says: “You will have all this if you live in such a way that you give evidence of your faith by shunning worldly lusts.”

Notice how Luther, at the end, puts sanctification in there! Outstanding, I’d say. He’s a master teacher because he’s a master listener at the feet of the apostles: Even though we’re saved by faith alone, genuine, saving faith is never devoid of love, the “evidence of your faith.”

Talking about promises and faith, for Lutherans this invariably means that we’re talking about Christ—not as absent (at least according to his human nature), but as present in us according to both natures. Primarily as the bringer of our justification, but secondarily also as “engine” of our sanctification.

The reference to 2 Peter 1:4 in SD VIII, 34 drives Christ’s presence in us home:

St. Peter testifies with clear words that even we, in whom Christ dwells only by grace, have in Christ, because of this exalted mystery, “become partakers of the divine nature” (2 Pet. 1:4), what kind of participation in the divine nature must that be of which the apostle says that “in Christ the whole fullness of the deity dwells bodily” (Col. 2:9) in such a way that God and man are a single person!

From this we learn: Christ, here identified as “the divine nature” (synecdoche — a “part” for the whole), dwells in us Christians by grace (that is, by faith in the gospel promises mentioned by Peter, cf. Eph. 3:17!). The gifts Luther identified with the “divine nature” cannot be isolated from Christ’s / God’s presence (cf. Ep. III, 18). The way this divine nature dwells in us is different from the way this same divine nature dwells in Christ bodily.

At any rate, this indwelling of the divine-human Christ our confessions call our “highest comfort” (SD VIII, 87):

Hence we consider it a pernicious error to deprive Christ according to his humanity of this majesty. To do so robs Christians of their highest comfort, afforded them in the cited promises of the presence and indwelling of their head, king, and high priest, who has promised that not only his unveiled deity, which to us poor sinners is like a consuming fire on dry stubble, will be with them, but that he, he, the man who has spoken with them, who has tasted every tribulation in his assumed human nature, and who can therefore sympathize with us as with men and his brethren, he wills to be with us in all our troubles also according to that nature by which he is our brother and we are flesh of his flesh.

This is quite an amazing text. Is it not? We’re not alone, according to the promise.

Evidently, this doesn’t mean, as you fear, that we look for lasting comfort within us (even though we should be able to detect something, even something seeming insignificant, of the new life within us — if not, where’s the fruit of our faith? — but finally, even that something is corrupted by sin — hence, lasting, final comfort in temptations we find in the objective promise offered to all in the means of grace). We still look to the promise outside of us. But that promise assures us: Christ is with us, even within us, with his gifts and with his human nature, according to which he is our brother and we are flesh of his flesh: Comforting and leading us; pleading and interceding for us; strengthening us during our time in the church militant in our battles against the sinful flesh we wage to drive the old Adam back more and more in the power of the Holy Spirit.

This quote, I submit, gives a glimpse at the fullness of the biblical gospel that is all the more surprising because that gospel comes to us in very humble, simple external forms that, by Christ’s institution, contain nothing flashy or glittery.

Your formulations at the end of your section on EO I find, therefore, in need of correction: Of course, we want a Christian life that’s visible! Why else does Paul exhort us to “put on” the new man (Eph. 4; Col. 3)? If you “put on” something (not just a show, but, e.g., clothes), it becomes visible.

This is not automatically an error. It becomes an error if, as I said above, this visible sanctification is mixed in with justification (and to the extent the EO or anybody else do this, they are in error, no matter what their terminology—plain and simple). Hence Luther’s sound advice: leave your good works between you and your neighbor and cling to God by faith alone. But those good works are visible. If not, what about the visible fruit of faith? Faith is invisible. True enough. So is our perfect righteousness and holiness. Our life before God, so to speak. But as we also must relate to our neighbor in this life, our Christian-ness must become visible. If it doesn’t, not even in some incipient way, it’s also not somehow “invisibly” present before God. Of this Scripture and the confessions assure us.

This shows, as I pointed out earlier, that this discussion is not really about “theosis” (red herring alert!!) but about sanctification in the life of the Christian. Period.

On to the Roman model, as you describe it! Here again, as stated above, to the extent Rome mixes our incipient renewal in love with our standing before God, it is in error, whether it expresses this error in Greek, Latin, Hebrew, German, Norwegian, or any other language or terminology.

However, I think, again, that your presentation of what Luther taught against Rome is in need of an important correction: Luther did not reject the notion of “infused grace” out of hand (in terms of the Spirit’s gift/power in us, enabling us to do the Ten Commandments). He rejected it when it was mingled into the article of our justification before God.

In fact, he condemned the antinomians of his time for not teaching “infused grace.” Trent already quoted that text earlier. But I think it bears repeating at this time because it is really, really important that we don’t fall into false dichotomies here (AE 41:114—from his 1539 treatise on the church and the councils, also available from Lutheran Press, by the way):

Christ did not earn only gratia, “grace,” for us, but also donum, “the gift of the Holy Spirit,” so that we might have not only forgiveness of, but also cessation of, sin. Now he who does not abstain from sin, but persists in his evil life, must have a different Christ, that of the Antinomians; the real Christ is not there, even if all the angels would cry, “Christ! Christ!” He must be damned with this, his new Christ.

Harsh, but necessary words from the chief teacher of our church—spoken not when he too was a “Lutheran” neophyte (in 1517), but as a mature leader of the emergent Lutheran church in 1539, as that church was preparing for the long-awaited general council of the entire Western Church.

And as I wrote in my first post, we need to be careful not to play off the indwelling of Christ against the indwelling of the Holy Spirit. After all, the Spirit is Christ’s Spirit who proceeds from him and the Father and takes what is Christ’s and makes it known among us, John 16:14 (there’s also a great sermon by Luther on that text available from Lutheran Press).

We could even say with Augustine: the outward works of the Trinity are indivisible, unlike the inner-trinitarian relations, as Luther affirms in his 1543 Treatise on the Last Words of David (AE 15:302):

If I ascribe to each Person a distinct external work in creation and exclude the other two Persons from this, then I have divided the one Godhead and have fashioned three gods or creators. And that is wrong. Again, if I do not ascribe to each Person within the Godhead, or outside and beyond creation, a special distinction not appropriate to the other two, then I have mingled the Persons into one Person. And that is also wrong.

A little later (p. 309) he applies this to the question at hand: “the Holy Ghost sanctifies Christendom, so does the Father, so does the Son, and still there are not three sanctifiers, but only one Sanctifier, etc. ‘The works of the Trinity to the outside are not divisible.'”

So, instead dividing miserly and wrongly, we should rejoice in the richness of God’s mercy toward us poor, miserable sinners, as it is revealed to us in Scripture (cf. the Smalcald Articles on that richness).

Now, we could go through your presentation of Osiander, the Finns, the Emergers, the Perichoretics, or whoever—my line will always be: to the extent they mix our incipient renewal (and that includes confidently and correctly sharing the faith with those who do not know it) with our justification before God, they are in error and are badly misleading people.

However, that said, this is not a necessary consequence of believing and teaching that the triune God dwells in us and permeates us, that we are partakers of the divine nature! It is not a necessary consequence of exhorting Christians to a life that is visibly worthy of their calling.

As you’ve seen above—or at least as I’ve tried to demonstrate above—this is all taught by our sound Lutheran teachers, even by Scripture itself. We’d do a disservice to the Church if we dumped all this out. In fact, we’d cease to be a Christian church.

The error is, rather, a necessary consequence of their legalistic doctrine of justification. E.g., evangelicals of various stripes suffer from this, even those, I’d venture to guess, who would reject any association with, or who are totally ignorant of, the labels “theosis,” “perichoresis,” “indwelling,” etc.

It’s a problem of their doctrine of justification. As Luther said, if you get that one wrong (or even ignore it), you’ll get everything else wrong as well.

Now, as I’ve said in my first post. This is one discussion we obviously and urgently need to have. Your post is the best evidence for it, if I may say so.

Another discussion we then also need to have is terminological in nature: should we call what the Lutherans soundly teach on our increasing holiness and heavenly perfection “theosis”? Here I’d say no. I liken this to the attempt by some in our circles to rename the worship service as “mass” (or its EO pendent, “divine liturgy”) because, in their minds, “worship” is somehow automatically “evangelical” and “anti-sacramental.” Now, did Luther call worship “mass”? Yes. Did the confessional writings authored by Melanchthon in 1530/31 call it “mass”? Yes. Should we today? No.

Why? It’s not essential to our faith to do so. And we haven’t been doing it for a long time, in part, no doubt, upon Luther’s 1534 advice (cf. AE 38:226f.). So now that term has become exclusively associated with the Roman Catholic Church and their utterly false understanding of the Supper. The same would be true of pastors calling themselves “fathers.” Theologically legitimate, if understood properly (see LC on the Fourth Commandment), but unfortunately misleading today.

Here terminological restraint is a good work of Christian love that’s also external and hence both visible and audible. Terminology is, to a good measure, part of the vast area of “adiaphora,” things neither commanded nor forbidden by God but introduced by the church for good reasons, i.e., here for the explicating and defense of the biblical faith.

Restraint and uniformity in these areas out of humble love—not an inconsiderate striving for novelty or an “anything goes” attitude—are essential to preserving the unity of the Church in the one true faith. It’s kind of like our worship services, as we’re all painfully aware.

My two cents.

November 13, 2014

C.F.W. Walther on Sanctification

In a recent comment on this site Rev. Paul T. McCain offered a snippet of a sermon by C.F.W. Walther. I reproduce it here for your edification. Thank you, Pr. McCain!

By way of a preface, McCain writes: “Here are some great quotes from a model sermon demonstrating how Lutherans faithfully preach and teach about justification and sanctification, as well as how proper Biblical parenesis is a part of their sermons.”

Here’s Walther:

Yes, I know that he looks like El Chupacabra in most of the extant photos, but wouldn’t you like to be remembered with one of your better pictures?

+ + +

The question is not whether we are already perfect, for that is impossible in this life; the question is only whether we are among those who actually pursue the goal of sanctification, or whether we still are secure and dead in sins. If we are among those running the spiritual race, if we pursue this treasure, how happy we are! That is a sign that we are made alive through grace.

Justification is instantly complete because everyone immediately receives complete forgiveness of his sins, the entire righteousness of Christ, and each becomes a child of God as well as apostles Peter, Paul, and all the great saints. Sanctification, on the other hand, comes after justification. At first it begins weakly and though it must grow until death, it never becomes perfect.

The subject matter of sanctification is not how a person becomes righteous, but how a person who has already become righteous lives from day to day. It is is not about asking what the tax collector had to do to go home justified, but how the tax collector lived in his home after he returned justified.

Sanctification does not consist in this, that a person no longer curses, commits adultery or lives in the gross works of uncleanness, gets drunk, or openly deceives and lies. Even the heathen can abstain from such out and out vice; but sanctification consists in this, that the justified person becomes an entirely different person. … Even if he is busy at his earthly calling, he does it with a mind directed to God. He also begins to watch over his thoughts and desires; no longer can he indifferently let evil thoughts go through his mind and if they do arise, he prays against them. He hates sin; he no longer fosters sin with great care. He does not let them rule over his will, but battles against sin, even his pet sins. If out of weakness he heedlessly falls into sin, he does not continue in it but is ashamed of himself, and confesses it to God with heartfelt humility and prays for forgiveness. He lets his fall serve as a warning, becoming only more humble and watchful over himself.

Dear friends, you who are even now engaged in this struggle, continue courageously in it. Do not spare yourself. Do not fight in your own power, though; daily draw from the fount of divine grace in Christ Jesus and you will not fall fatally injured but will finally carry the field and obtain the victory. Amen.

[From a sermon on Mark 7:31-37 by C.F.W. Walther (Gospel Sermons, Volume 2, CPH: 2013)]

Related Posts:

“Man’s Working Together With God After Conversion” -or- “C. F. W. Walther was a dirty pietist, evidently”

“The Restoration of the Divine Image Through Christ” ~ A Sermon by C. F. W. Walther on Mark 7:31-37

Selected Sermons of C.F.W. Walther, American Lutheran Classics Volume 9

The Proper Distinction Between Law and Gospel by C.F.W. Walther, American Lutheran Classics Volume 7

+SDG+

November 12, 2014

What does the sanctified life actually look like?

All of this discussion about sanctification has sometimes gotten into abstract categories, and there has been much misunderstanding. There have been some forums where people have asked questions like: “what does piety actually look like?” and we have not addressed such issues well. So here is a practical illustration of what it actually looks like to live a life of sanctification (note that the “I” is a hypothetical individual, lest anyone think I am setting myself up as some kind of examples of holy living):

I wake up in the morning, and make the sign of the cross over myself. I remind myself of who I am in Christ by Holy Baptism, and ask for God’s help to love and serve my neighbor throughout the day as I pray Luther’s morning prayer.

During the day, I try and treat others well in my job, and perform my duties well. I see that someone at the office is having a bad day, and I give them a word of encouragement. I take time to make sure that I treat customers well, and listen to their needs, even when I really don’t want to. I try to avoid the gossip going around at work, and only speak highly of other people. When the opportunity arises, I speak to others about the love of God in Christ Jesus.

I come home and try to be patient and loving toward my wife and children. My wife reminds me of something that I said which was offensive to her. I confess my sin immediately, ask for her forgiveness, and sincerely ask God to help me to treat her better in the future. In the evening I spend time in family worship, praying and reading Scripture with my wife and kids. I support my wife’s decisions regarding the children, even if I would not have made the same decisions. I make sure to tell my kids about the love I have for them, and about the love that Christ has for them.

At night, I go to bed and go back through my day. As I reflect on my day, I remember all of the things I have done wrong. I remember that I got really angry at work, and that I didn’t give my wife the attention she deserved. I recall some really mean thoughts that I had about my coworkers. I realize that my mind was drifting off during family worship, and that I was not really focused on God. I confess these sins to God, asking for his forgiveness in Christ and for help to follow God’s will the next day through Luther’s evening prayer. Finally, I go to bed with joy and full assurance of my salvation in Christ who forgives sinners. The next day begins and the cycle happens again.