Brian Cuban's Blog, page 10

June 29, 2018

A Drunk Lawyer Walks Into An Airport…

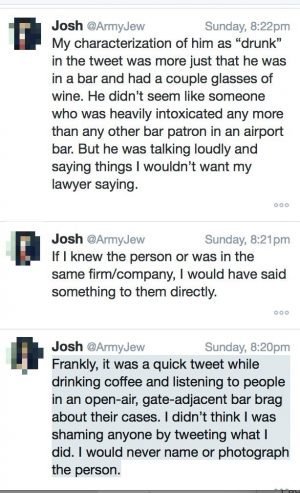

Sounds like the start of a great lawyer joke. In reality, according to the tweeter “Josh,” also known as ArmyJew, the lawyer was already in an airport at a bar. Josh tweeted about it. According to him, the lawyer was “drunk” and loudly spilling what Josh perceived to be privileged client information.

The tweet screen-cap is below. I have obscured the name of the law firm and airport to do my part in not making it worse for the “drunk lawyer” while understanding that there is no way to use this tweet as a discussion vehicle without posting it. Josh has no personal or professionally identifying information on his own Twitter bio, so there is no danger of publicly shaming whoever the person is behind that account. I have also obscured Josh’s avatar because it appears to be a child. Josh has since deleted the tweet in question and all other tweets related to the topic, but not before continually defending his action against anyone who suggested it was ill advised.

Josh’s drunk lawyer tweet went moderately viral and engendered a range of responses from amusement and disbelief that anyone would have a problem with his tweet, to anger that an lawyer would embarrass and potentially jeopardize the standing of a fellow member of the profession by including information that would make it easy for the law firm to figure out who it was. This is, of course, assuming anything in the tweet was true in whole or in part. We all know how Twitter is about truth and exaggeration.

Let’s assume for purposes of discussion that it is all true. Josh observed a drunk lawyer in an airport spilling what Josh believed to be client secrets. What happens next? What should happen next? What Josh thought should happen is self-evident. He tweeted about it and went on his way.

In my opinion, Josh was at a minimum, an asshole for tweeting specific firm information that could potentially identify the lawyer and subject him to shame and possible job consequences. There were other ways to go with this, the least of which would be for Josh to simply ignore it. Don’t tweet. Don’t potentially embarrass some random, drunk lawyer at the airport by putting him on Twitter blast. Do nothing and catch your flight. Mind your own business.

Being a tweeting asshole aside, should we mind our own business in such a situation? When we witness a legal colleague behaving in the way Josh describes? Many I have discussed this with think we should. We all have our own airport lives to deal with. The work day. Family. Our own personal problems. Maybe headed to a vacation with family. Who needs that added drama or potential confrontation?

I totally get that. Can’t say that I would not feel the same in that moment. No one likes confrontation. We tend to project out the worst possible result. Much easier to just mind our own business. I’ve been told to mind my own and worse in my life with regards to approaching people who are struggling. That’s okay. The sun still rose the next day. Now and then someone actually wants the help and is receptive.

Would I do it in an airport? I know myself well enough to know I would at least go through the thought process of what to do. After that? I may not confront the person, but I’d like to think I would come up with an alternative way to handle it.

I am not a legal ethics guru, but it seems another possible issue is whether any professional responsibility obligations were potentially triggered. I will assume all jurisdictions have some form of the “Squeal Rule” mandating reporting of misconduct to the state bar, or in the alternative, an approved peer assistance program if the witnessed situation involves chemical dependence or some other form of mental health issues. The issue here is of course that Josh’s perception of what is going on probably does not amount to actual knowledge that a bar rule has been violated. Is there even enough information to make that report? More than one lawyer has commented that they were be concerned that if they intervened and became aware of more information, then a such responsibility could be triggered.

I reached out to Josh for comment. His responses are below. He was aware that they would be published in this column.

I don’t think there is any right or wrong answer for Josh’s particular situation. Every person will look at this based on their own life experience whether the choice is to ignore it, confront the lawyer, or even do some digging to contact the firms Employee Assistance Program and let them know. I know that seems extreme and even silly to some but that’s how my mind works. Examining all possible responses to possibly help someone.

Well, there is one absolutely wrong answer here. Don’t be an asshole and tweet about it. At a minimum, do no harm.

Brian Cuban (@bcuban) is The Addicted Lawyer . Brian is the author of the Amazon best-selling book, The Addicted Lawyer: Tales Of The Bar, Booze, Blow & Redemption (affiliate link). A graduate of the University of Pittsburgh School of Law, he somehow made it through as an alcoholic then added cocaine to his résumé as a practicing attorney. He went into recovery April 8, 2007. He left the practice of law and now writes and speaks on recovery topics, not only for the legal profession, but on recovery in general. He can be reached at brian@addictedlawyer.com .

June 13, 2018

Suicide As A Selfish Act?

I won’t rehash the facts of my awful summer of 2005. My brothers dragging me kicking and screaming to a psychiatric facility. You can read about it here. I will instead focus on my state of mind at that time. I remember. I ordered my psychiatric records from that visit. They were not pretty to read, but it was cathartic.

From memory and the records, one thing is clear. I had no concept of “selfish”. I felt I was doing my family a favor in being rid of me. It was to be my final act of love. No one sitting in that small room as I cried, yelled and vented my hopeless and pain told me I was being selfish. They simply listened.

There is no way to know for sure, but looking back and knowing what I was feeling(and not feeling), I believe that if a family member or friend would have called me and told me I was being “selfish” in my thought process, that I should consider the people I was leaving behind, my probably response would have been one of anger not, acknowledgement. Something like:

“F#ck off. I know exactly what I am doing and my family consideration is primary.

There probably would have been no further opportunity for intervention.

I would have seen it as an attempt to shame me and an “I will show you” mindset could have very well resulted in the worst possible result before anyone could get to me.

Of course, this is all speculation and what happened was the best possible result. Friends and family did not mind their own business. They did not try to shame me. They listened. Trained professionals did their job. I am alive.

I do understand that when some label suicide as “selfish”, it is in reality, a self-defense mechanism to cope with an unfathomable act. Even when it’s people we don’t know, we need a way to relieve the pain we feel for the survivors.

It is normal to look back and wonder what opportunities there were to intervene and what signs were missed. This can naturally trigger intense guilt. We have to find an outlet for that guilt. We can no longer talk to the person who took his/her life so we label the act as “selfish”.

To get a clinical perspective, I reached out to someone who deals with suicidal ideation on a regular basis. Dr. Kelly Jameson Ph.D. Here is what she has to say:

The recent deaths of Kate Spade and Anthony Bordain have again sparked great debate about the field of mental health. As a therapist in private practice in Dallas, Texas and let me begin by stating that I do not suffer from depression, nor have I ever had thoughts of suicide. This is important to note because as a mental health professional, I need to constantly remind myself of this fact when working with someone who is suffering from depression. Why? Because their experience of depression is so profound that despite my extensive training, I don’t have a clue about what this truly feels like. Sure, we all have our lows, but even my worst day is miles away from an average day of a person with severe depression.

I specialize in teens, and to say that I’m desensitized to talk of suicidal ideation is an understatement. This isn’t to say I’m callous or cold, but to work in mental health means to be well-versed in suicidal ideation, as well as thoughts, planning and active suicidality. When a teen or adult is bold and brave enough to share they are passively or actively suicidal my mind immediately begins the task of organizing, filtering and categorizing the way they are narrating their suicidality. What are the next steps to ensure their safety?

Here are a some of my most vivid memories of the way some patients have described their depression and suicidal thinking.

“My depression rolls in like waves, not unlike the ocean tide. When I was younger, I would try to fight it or ignore, but now I honor it. I let it roll through me and I respect it. I do that by practicing my best self-care and wait for the wave to pass. Sometimes it a few days, or a week, but I’m old enough now to know that it will pass.”

“It feels like a large, massive brick wall literally pushing up against my brain, I can almost see it if I close my eyes. It’s heavy and strong and dark. When I take my medicine, I can feel it working against the brick wall. It’s like a battle going on inside of me and I’m just the arena in which it takes place.”

“My depression feels like an electricity within me. Like I could plug myself into an outlet and explode. It’s like I’m not even human, but a series of circuits that are over-wired and about to blow.”

Depression is unique, like a fingerprint or snowflake. I’ve learned to abandon the usual intake questions about depressive symptoms and just ask really open questions about their relationship with their depression, and it always provides powerful insight about where they are with their disorder. Yes, depression has classic symptomology but the emotional response to the disorder is quite varied, which is why many caring individuals miss it. Many look for the “usual” characteristics and if someone’s relationship to this depression doesn’t fit the box, it is assumed to be something else, like ADHD or anxiety.

So, is suicide a selfish act? I used to think so. It’s true, many years ago I, too, used to think suicide was a selfish act, especially if children were involved…then I entered the mental health field. Boy was I wrong. Really wrong. Now, as I sit with patients who are passively or actively suicidal, I can tell you many of them see it not as a selfish act, but as a selfless act, a way to unburden their loved ones. Some adult men have referenced it as a way to finically save their family, others as a way to end chronic pain, and many, many teens (countless at this point) verbalize it as a way to relieve their parents of the shame and embarrassment they believe they have brought upon their families by their mistakes, bad decisions, or inability to achieve success in academics or sports.

Depression is a hope stealer. It is the belief that the way you are feeling now will never change and there is no point in trying. It is the ultimate con artist, a traveling salesman that persuades you to think that dying will liberate your loved ones and free you of all pain. For those who are in the depths of depression, the traveling salesman is selling a product they think they need, like a late-night infomercial that convinces you (if you sit there long enough and watch) that this hair serum WILL regrow your hair! To say that suicide is a selfish act is not only unfair, but idiotic. Your brain chemicals are ridiculously powerful, and unless you’ve experienced these complete emotional drains yourself, my best advice to you is this: hush. You. Don’t. Know. Even as a mental health professional, I do not make quick “You should just do this” statements to patients with depression. It’s so strong of a disorder it requires a delicate handling of treatment. That might seem backwards but the risks are so high, it requires a great and thoughtful level of care which takes time, a long time. Much more time than to haughtily declare suicide as a selfish act.

National Suicide Prevention Lifeline. 800-273-8255

Brian Cuban (@bcuban) is The Addicted Lawyer . Brian is the author of the Amazon best-selling book, The Addicted Lawyer: Tales Of The Bar, Booze, Blow & Redemption (affiliate link). A graduate of the University of Pittsburgh School of Law, he somehow made it through as an alcoholic then added cocaine to his résumé as a practicing attorney. He went into recovery April 8, 2007. He left the practice of law and now writes and speaks on recovery topics, not only for the legal profession, but on recovery in general. He can be reached at brian@addictedlawyer.com .

June 12, 2018

I’m Alive Because People Did Not Mind Their Own Business

Whenever there is a high profile, celebrity suicide in the news, the social media reactions are fairly predictable. Shock. Disbelief. Thoughts and prayers to the family. Wondering how someone who outwardly “had everything” could be depressed. Statements of how selfish the person was (especially if children are left behind).

It irritates me when people parse a public tragedy like Kate Spade or any suicide as “selfish” but I also get that it is a way people deal with the unfathomable by placing blame. It’s coping. I don’t like it. I wish people would not do it, especially publicly, because it stigmatizes mental health awareness.

Posting the Suicide Hotline is great as a way of coping. It’s important. It’s awareness. When we feel helpless and hopeless, it’s a way of doing something to raise awareness. Maybe someone will use it. Maybe a life will be saved.

I’d like to offer one more thing on the ground level that everyone reading this can do. You don’t need a counseling degree. You don’t need any knowledge of how depression and suicidal thoughts work. We all have the ability to do it.

It is this:

Do not mind your own business. Even when “butting in” is uncomfortable. The only reason I am here today writing this is because three people did not mind their own business in the summer of 2005.

During that summer, after years of struggling with depression, addiction, eating disorders and body dysmorphic disorder, I lost all hope that I would ever look in the mirror and see someone that I loved. Someone would ever be loved by anyone else.

In those dark moments, it made perfect sense to me. I would be doing my family a favor to rid them of the burden I had placed on them. I did not see a selfish act. I had no concept of “selfish”. In my mind, it was an act of love. It would be a relief for them to be rid of me.

As the darkness grew deeper and more hopeless during that week, a switch flipped. Maybe I was unconsciously reaching out for help. I began emailing with a friend of mine who noticed that my emails had a suicidal tone and also knew that I had a weapon that he actually had given me as a birthday present years before. He was an avid vintage gun collector.

During that week, I was drinking heavily, snorting cocaine and taking black market Xanax like candy to sleep away each day without facing my pain. In waking moments, I began practicing the act with the weapon unloaded.

My friend called me. I didn’t answer the phone. He then emailed my two brothers Mark and Jeff. Jeff came to the house first. The weapon was on my nightstand. The room was littered with drugs and alcohol bottles. He took the weapon. Mark showed up next. They cleaned up the room and took me in Mark’s car to Green Oaks Hospital in Dallas, kicking and screaming. They were trying to save me life and I just wanted to be left alone to die. I remember walking out of the house and my brother Jeff saying that I had a drug and alcohol problem and Mark saying that it was depression. They were, of course, both right.

I would not find drug and alcohol recovery for almost another two years but there is no doubt in my mind that I am only here to today because three people did not mind their own business. My friend could have taken the comfortable route and avoided an unpleasant conversation with my brothers or worry that he was butting in to my business.

Instead, he started a chain that saved my life. Would I have used the weapon in those moments if he had not? I know that I fully intended to but of course, the fog of the suicidal mind versus a cry for help is often difficult to determine in the moment. If he had decided it was just “drama” that may have only been clear in the aftermath of a tragedy. There is no going back from such a thing.

I am glad my friend Angelo and my brothers did not mind their own business. I am glad to be alive.

Not minding your own business will not save everyone. As long as there is human suffering, there will be this type of tragedy. We cannot be there every moment of the day when someone is struggling and I know from experience that the thoughts and desire to act can come on very fast without warning to anyone else. Not minding your own business however, may be the one moment that you need to save just one person by interrupting a terrible, dark process. Take that chance. Be uncomfortable. Reach out. Interrupt.

Brian Cuban (@bcuban) is The Addicted Lawyer . Brian is the author of the Amazon best-selling book, The Addicted Lawyer: Tales Of The Bar, Booze, Blow & Redemption (affiliate link). A graduate of the University of Pittsburgh School of Law, he somehow made it through as an alcoholic then added cocaine to his résumé as a practicing attorney. He went into recovery April 8, 2007. He left the practice of law and now writes and speaks on recovery topics, not only for the legal profession, but on recovery in general. He can be reached at brian@addictedlawyer.com .

June 6, 2018

I’m Alive Because People Did Not Mind Their Own Business

Whenever there is a high profile, celebrity suicide in the news, the social media reactions are fairly predictable. Shock. Disbelief. Thoughts and prayers to family. Wondering how someone who outwardly “had everything” could be depressed. Statements of how selfish the person was (especially if children are left behind).

It irritates me when people parse a public tragedy like Kate Spade or any suicide as “selfish” but I also get that it is a way people deal with the unfathomable by placing blame. It’s coping. I don’t like it. I wish people would not do it, especially publicly, because it stigmatizes mental health awareness.

Posting the Suicide Hotline is great as a way of coping. It’s important. It’s awareness. When we feel helpless and hopeless, it’s a way of doing something to raise awareness. Maybe someone will use it. Maybe a life will be saved.

I’d like to offer one more thing on the ground level that everyone reading this can do. You don’t need a counseling degree. You don’t need any knowledge of how depression and suicidal thoughts work. We all have the ability to do it.

It is this:

Do not mind your own business. Even when “butting in” is uncomfortable. The only reason I am here today writing this is because three people did not mind their own business in the summer of 2005 .

During that summer, after years of struggling with depression, addiction, eating disorders and body dysmorphic disorder, I lost all hope that I would ever look in the mirror and see someone that I loved. Someone would ever be loved by anyone else.

In those dark moments, it made perfect sense to me. I would be doing my family a favor to rid them of the burden I had placed on them. I did not see a selfish act. I had no concept of “selfish”. In my mind, it was an act of love. It would be a relief for them to be rid of me.

As the darkness grew deeper and more hopeless during that week, a switch flipped. Maybe I was unconsciously reaching out for help. I began emailing with a friend of mine who noticed that my emails had a suicidal tone and also knew that I had a weapon that he actually had given me as a birthday present years before. He was an avid vintage gun collector.

During that week, I was drinking heavily, snorting cocaine and taking black market Xanax like candy to sleep away each day without facing my pain. In waking moments, I began practicing the act with the weapon unloaded.

My friend called me. I didn’t answer the phone. He them emailed my two brothers Mark and Jeff. Jeff came to the house first. The weapon was on my nightstand. The room was littered with drugs and alcohol bottles. He took the weapon. Mark showed up next. They cleaned up the room and took me in Mark’s car to Green Oaks Hospital in Dallas, kicking and screaming. They were trying to save me life and I just wanted to be left alone to die. I remember walking out of the house and my brother Jeff saying that I had a drug and alcohol problem and Mark saying that it was depression. They were of course both right.

I would not find drug and alcohol recovery for almost another two years but there is no doubt in my mind that I am only here to today because three people did not mind their own business. My friend could have taken the comfortable route and avoided an unpleasant conversation with my brothers or worry that he was butting in to my business.

Instead he started a chain that saved my life. Would I have used the weapon in those moments if he had not? I know that I fully intended to but of course, the fog of the suicidal mind versus a cry for help is often difficult to determine in the moment. If he had decided it was just “drama” that may have only been clear in the aftermath of a tragedy. There is no going back from such a thing.

I am glad my friend Angelo and my brothers did not mind their own business. I am glad to be alive.

Not minding your own business will not save everyone. As long as there is human suffering, there will be this type of tragedy. We cannot be there every moment of the day when someone is struggling and I know from experience that the thoughts and desire to act can come on very fast without warning to anyone else. Not minding your own business however, may be the one moment that you need to save just one person by interrupting a terrible, dark process. Take that chance. Be uncomfortable. Reach out. Interrupt.

Brian Cuban (@bcuban) is The Addicted Lawyer . Brian is the author of the Amazon best-selling book, The Addicted Lawyer: Tales Of The Bar, Booze, Blow & Redemption (affiliate link). A graduate of the University of Pittsburgh School of Law, he somehow made it through as an alcoholic then added cocaine to his résumé as a practicing attorney. He went into recovery April 8, 2007. He left the practice of law and now writes and speaks on recovery topics, not only for the legal profession, but on recovery in general. He can be reached at brian@addictedlawyer.com .

May 31, 2018

What Law Students Want From Law Schools On Wellness

Getting a law student to speak openly about mental health is difficult. There is, however, a forum in which they tend to be very candid and blunt on a variety of topics. It is the Reddit Law School Forum. I spend a lot of time there because I can see what law students are really thinking without filter on the topic of wellness. It is anonymous. I put a simple question to the forum:

“How Can We Better Support Law School Wellness?”(I made it clear the responses would be used for an article. No anonymity was compromised)

Here are the unedited responses. I hope all law school administrators will look at these comments and evaluate how they apply to your school. In the law schools I have spoken at, I know that many of these suggestions are already part of the wellness plan. How about your school?

“I think C&F (Character & Fitness) causes a lot of anxiety for people with mental health troubles. When you have to report seeking help or a diagnosis of mental health for review by a committee of strangers, it may seem better to self-treat or simply not seek health care.”

“It’s not true that schools can’t take measures to minimize the anxieties students experience in relation to C&F. For instance, schools can provide a confidential means for students to inquire what facts should or should not be revealed, guidance on how to accurately disclose relevant incidents, or recommendation to counseling services so that the person has someone to talk to about either anxiety related to C&F or the incidents in their past that warrant disclosure, to name a few.”

“Would love if my University (with an endowment over 10 billion) actually invested in mental health care. Telling new students in September that the next available appointment is in November is disgusting.”

“Don’t schedule the Mental Health Day activities on top of a mandatory 1L info session. We were all too busy for Mental Health Day.”

“Law school administrators need to fight to make counseling easily accessible for students. I knew a lot of students going to school far from home who couldn’t find a private provider covered by their insurance. I also knew too many people who were dealing with mental health issues in the first place because they felt overwhelmed — trying to find a covered provider only added to their anxiety. At my large university, counseling was available from the university health system, but students were limited to a certain number of visits a semester. Med students, thanks to advocacy by their administrators, are the only group on campus that gets unlimited visits. Law students should have the same type of deal.”

“Law schools need to encourage students to define what success means FOR THEM early on. Not everyone will make law review or moot court or book a class. That’s ok. Not everyone needs those things to do what they want to do. But when you’re in the thick of it — especially fall semester of 2L year when it feels like everyone is getting sorted all the time (journals, moot court, OCI) — it feels like those traditional markers of success are THE ONLY things that”

“Law school administrators are never going to fight for something that does not directly increase profit or prestige.”

“An onsite therapist would help, with potentially one mandatory, one-hour meeting during fall of 1L.”

“I could get behind one mandatory meeting. The problem you’ll run into, unfortunately, is staffing. My school’s mental health center is already understaffed. I think this is a great idea, though.”

“I completely agree. I think this is more idealistic than realistic. I started therapy after I lost my dad during Spring 2L finals. While my therapist helped guide me through that loss, the lessons she conveyed greatly assisted me with stress management and anxiety during my 3L year.”

“We don’t have mandatory sessions, but we have an on-site therapist with walk-in hours and appointments. She also has a J.D. from a T14 so she has a good reference point for understanding students.”

“There seems to be a focus on students with good grades, the top 25% got invited to a dinner with the dean and to me, that seems like it creates an elitist mentality which makes me think they don’t really care about you if you don’t have high grades, and I’ve always been an average student. It really makes me feel even more depressed by it.”

“Same at my school, but we are located in a very small and insular market so add to this a focus on students whose parents/close family were donating alumni. I don’t think the administration of my school cared at all about reaching out to first generation students, but instead spent all their focus on the students that already had professional connections and a sense of what to expect from law school due to their families. That was something I wasn’t prepared for at all going into law school, and weighed on me a lot 1L year on top of all the other stress I was facing.”

“I don’t even think my campus has anything like that. I think that’s a good first step — studying the absence of a facility/resource like that on the actual law campus. Maybe look at the distance between the law school resource and the facility (if any) on the main campus, and how far away it is.”

“Encourage the wellness branches of law schools to plan with and even push back against faculty. Obviously, law school is hard, but there were a few weeks in 1L where there were major things due across multiple classes, combined with short notice assignments and other fuckery. The overall workload doesn’t feel that problematic, more just the way it is organized. I’m not a mind reader, but it felt like there was a certain amount of hazing/reveling in the glory of work attitude about those 16-hour-days-for-weeks periods from the faculty.”

“Student-focused initiatives are nice of course, but if you don’t address the actual academic culture, then law schools will just continue talking out of both sides of their mouth. Maybe these conversations already happen behind the scenes, I don’t know. Just my thoughts.”

“I think that this is beyond the scope of law schools to effectively manage. It’s an industry problem that just happens to start in law school. My school has really high employment rates, and three therapists who have open drop in hours in the law school building (in addition to the ability to make an appointment with the counseling center across the street). I still had multiple friends who had mental break downs in law school, and one who attempted suicide. Other than the one who attempted suicide, they were all median students with Biglaw jobs lined up after graduation and they all got their initial treatment at school. Having treatment so close is helpful, but it didn’t prevent the problem.”

“Making it accessible, for one. My school hired a counselor during my 2L year and apparently there was a lot of outreach to the 1Ls, but I never found out how to even schedule an appointment, or if there would be a cost. Also, I know the check-in process is with a student in an office with several other functions, so it was pretty likely that if you went in there, you’d be seen. That’s a deterrent for law students, who are generally bad at admitting they need help.”

“The other downside is that the hours are limited: Monday through Friday, 8:30 a.m. to 5 p.m. That might be do-able as a 1L, but my 2L and 3L years I was working/clerking and often not on campus during those hours. So for me, the service was basically unavailable. On a side note, one weekend a girl at the school was attacked (I was the one to find her). It would have been really helpful to have someone with counseling skills on hand for her, but the weekend security guard was useless and only succeeded in making her even more uncomfortable than she already was.”

“But even if law schools address this better, it’s an industry problem. Most of us are still going into the world of billable hours, unreasonable expectations, and never-ending debt. Law school was hard, but I think it’s going to feel like an oasis when I get my first job.”

“Our school just started a mental health student alliance of sorts. We have on-campus counselors, but we share them with other schools in the university system, and they are stretched very thin. I think the med school has their own in-house dedicated staff position for student wellness — we are pushing for something similar at the law school.”

“Make sure people actually want to become lawyers and are not just bypassing the real world by attending law school. When they bypass the real world for something they don’t actually like, their hole gets deeper and harder to get out of.”

“It’s pointless unless practice changes as well.”

“The only thing you can do is support students with food and supplies, to take stress out of day to day activities to ensure they are well prepared. My school stopped letting LSOs use SBA fund to supply food at events, and it has (anecdotally) led to a lack of attendance at LSO events, which is pretty sad.”

Brian Cuban (@bcuban) is The Addicted Lawyer . Brian is the author of the Amazon best-selling book, The Addicted Lawyer: Tales Of The Bar, Booze, Blow & Redemption (affiliate link). A graduate of the University of Pittsburgh School of Law, he somehow made it through as an alcoholic then added cocaine to his résumé as a practicing attorney. He went into recovery April 8, 2007. He left the practice of law and now writes and speaks on recovery topics, not only for the legal profession, but on recovery in general. He can be reached at brian@addictedlawyer.com .

May 15, 2018

The Bipolar Lawyer

In July 2005, I was taken to a Dallas psychiatric hospital in a suicidal depression. Years later in recovery, I ordered the records of that visit. One of the first things I noticed in the attending psychiatric physician’s notes was “rule out bipolar disorder”. I had never heard of bipolar disorder.

Here is the story of a lawyer who is dealing with bipolar disorder. What it meant to him before, during and after his diagnosis as well as moving forward in life. Reid Murtagh is a lawyer in Lafayette, Indiana. He writes often about his journey and mental health in general. His column, “Mental Fitness” can be found in The Indiana Lawyer.

Q: Where have you been in life?

It all started in Lafayette, Indiana a few months before the 1984 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles. Reagan was president and mullets were socially acceptable.

My mom was working as a P. E. teacher and my dad was working nights as a patrolman for the sheriff’s department. My sister came along 19 months later. Words can’t describe how much my parents loved us. We were the quintessential all-American family that exuded success at all times.

My dad was elected as sheriff in 1994 (later appointed by President George W. Bush as the United States Marshal for Northern Indiana). That made me the sheriff’s son, which was a blast. I was a straight-A student and painfully shy. I was obsessive about studying and my grades. I felt a lot of pressure to achieve but it was all internal pressure.

I had friends but not much of a social life. I did not drink alcohol or attend any parties where there would be alcohol. I went to a couple school dances and had a brief stint with a girlfriend. Other than being shy and a little awkward, I was a happy teenager.

Everything was pretty much going according to plan. I started my senior year and was applying to colleges. Then as fresh prince would say, “My life got flipped turned upside down.”

I went on a run after school. On my way home, I felt something I had never experienced before. This wave came over my body and all of the sudden I had no energy. I almost felt paralyzed. I felt like I was going to faint. I laid down in the grass on the side of the road. I didn’t know if I was going to be able to stand back up. I made it upright and walked for short periods and then laid back down and eventually made it home. This was the start of my first mental health crisis. I had recurring episodes of unexplained sensory and motor impairment. For several months I could not make it through the entire school day without having an episode during class. I would just shut down. I couldn’t keep my eyes open and I would have to put my head down on the desk. Someone in my class would help me walk to the nurse’s office. It was bizarre. I had never asked to be excused from class or even been to the nurse’s office before. I was diagnosed with generalized anxiety disorder. I started seeing a therapist who could meet with me at the school and I started taking Paxil. I still go to the same therapist today.

The therapy and the medicine pretty much resolved the symptoms and I was able to catch up the work I missed the fall semester and graduated in the spring. The relief I felt was so great that I stopped taking the medicine and stopped going to therapy. I was in denial. I continued without medicine or therapy until my third year of law school when I went to a psychologist and was diagnosed with cyclothymic disorder.

After I graduated from law school, I moved back to Lafayette and worked as a deputy prosecutor. Somehow, I acquired some dating skills along the way and fell madly in love with my dream girl and my future wife. I most certainly out punted my coverage.

I left the prosecutor’s office to work in a four-lawyer general practice private law firm. I was very productive my first three years and the seniors named me as a partner January 1, 2015. This should have made me feel very good. Instead, it triggered a major depressive episode.

I was in a very dark place for several months. I was no longer able to perform at the same level that allowed me to make partner. I tried to hide it. I could not admit to myself that I was underperforming. I placed the blame externally. I thought about leaving the legal profession and even told some people that I no longer wanted to be an attorney. Luckily, I reached out for help. I contacted the Indiana Judge’s and Lawyers Assistance Program. I was referred to a psychiatrist who changed my medicine. I was finally correctly diagnosed with bipolar II disorder.

I had already dug myself quite a hole at the law firm. I decided to leave the firm and start my own solo practice. Courtney, my wife, was pregnant at the time and our daughter was born in April 2016. As soon as I got my bipolar II diagnosis I knew I was going to share it publicly. I don’t know why but I just really felt that I needed to be more open about my private struggle. I decided that I wanted to publicly disclose my bipolar diagnosis in a meaningful way, but I had no idea how to do it.

I decided to share my diagnosis on Facebook. I then pitched the idea of the Mental Fitness column for the Indiana Lawyer and shared my diagnosis with the legal community in a published article in January 2017. The response to the article was overwhelming. All of the responses to my disclosure have been encouraging to this day.

Q: Where are you in life now?

After I shared the diagnosis, I faced another dilemma. I wanted to continue to help others, but I did not want to be known as the bipolar attorney. I did not want it to become my identity.

Now, I am fully committed.

I have realized that this is just part of who I am. You just don’t get many opportunities to do something like this in life. It was scary. I knew that people did not want me to do it. I knew that people did not understand. But I did it anyway. I am grateful that I did it for myself. I don’t know where it will lead and I am okay with that. I have a purpose.

I feel great. I am now in my third year of my solo practice. It has been harder than I anticipated. I have made mistakes as a business owner. I don’t have the security of the steady paycheck that I would have had if I stayed at the firm. My first priority has been my health. I have been able to come home from work and enjoy the time with my family. That is why I did all of this and that is my motivation to stick with it.

Q: What is your hope for the future and message to others?

I hope that people who want to disclose feel they can. Selfishly, I hope more people disclose. I hope more attorneys, judges, doctors, CEOs, and elected officials give themselves the gift of disclosure.

I hope we can start talking openly about suicide. I think we can push beyond general terms like anxiety and depression. Depression causes extreme or irrational negative thoughts. Anxiety causes extreme or irrational thoughts of fear or worry. Why can’t we talk about the negative thoughts? Why can’t we talk about the fears?

Such as:

Depression: What is the point? My life is so fucked up. Everyone else has a perfect life.

Anxiety: Fear of an early death. Fear of being ordinary. Fear of shame.

A lesson I have learned is that horrible and awful thoughts are not facts. When I am depressed, I have suicidal thoughts. During an elevated mood, fears of an early death often pop into my head. I know that I will continue to have these thoughts the rest of my life. I have no ability to control the thoughts in my bipolar brain. It took me a long time, but I have learned to accept that reality. Having irrational thoughts does not affect my ability to practice law or to be a loving husband and father. Those thoughts are powerless because I have learned to cope with them effectively.

I do the work. I make myself do things I don’t want to do. I take my medicine. I go to therapy. I value my recovery time. I have learned to love and care for my bipolar self.

Reid D. Murtaugh is attorney in Lafayette and the founder of Murtaugh Law. You can e-mail Reid at reidmentalfitness@gmail.com. Also, you can learn more about Reid’s practice at www.murtlaw.com.

Brian Cuban (@bcuban) is The Addicted Lawyer . Brian is the author of the Amazon best-selling book, The Addicted Lawyer: Tales Of The Bar, Booze, Blow & Redemption (affiliate link). A graduate of the University of Pittsburgh School of Law, he somehow made it through as an alcoholic then added cocaine to his résumé as a practicing attorney. He went into recovery April 8, 2007. He left the practice of law and now writes and speaks on recovery topics, not only for the legal profession, but on recovery in general. He can be reached at brian@addictedlawyer.com .

May 8, 2018

Hey Media: Please Stop Using The Word “Addict”

The Chicago Tribune recently published a powerful op-ed by a woman giving her personal story with regards to her sister’s lost struggle with opioid addiction. She talked about the shame that arises from the language used to describe her sister’s struggle. A wonderful piece. Vividly illustrating why language matters when talking about those struggling with substance use problems. The author states:

“ But it’s a chilling example of how derogatory language, stigma and denial render families helpless in this health crisis.

What was not so wonderful, and incredibly ironic, was the title of the opinion piece.

“Shame Won’t Help Opioid Addicts”.

I cringed when I read the title. It seems an editor at the Tribune did not get the message on the shaming and stigmatizing effect of describing people who struggle with substance use disorders as “addicts”.

This is not a crusade of a people trying make this an issue of political correctness. There is a wealth of data out there to support the damaging effect of such language. The Associated Press gets it. In 2017, they updated their stylebook to recommend that journalists use the term “person with addiction” instead of “addict”

Yes, “person with addiction” does not make for a nifty title that generates social media shares and hits. “Addict” has much more of a visceral and emotional impact. It still comes down to being part of the solution or part of the problem for a few more social media shares. AP has chosen to be part of the solution. The Tribune, in using this title is part of the problem.

I am no saint on this issue. I have also been part of the problem. I have not gone through every post of mine, but I suspect the term “addict” appears more than once. I am trying to do better and do my best to ensure that I never refer to another person in that way. Do I refer to myself that way now and then? I do. Again, I am trying to do better in describing my own journey.

I also have personal experience on this issue. On multiple occasions, I have been called a “Junkie”, Crackhead, Drug addict, and yes, “drunk, drugged up loser” as if there is a shaming manual that people read from. There is a shaming manual. It’s the media. People take their cues from what they read and here.

For another perspective on this, I reached out to a researcher who focuses on this issue and analyzing the data behind it. Robert Ashford, MSW is currently a PhD Student and Graduate Research Assistant at the University of the Sciences Substance Use Disorder Institute focusing on Behavioral Health Linguistics.

“For over 200 years in the United States, messages depicting substance use disorder and the recovery process have had a tangible impact on everything from public opinion to legislative policy.

Beginning the 1840’s, Temperance Societies partnered with popular media outlets to advance campaigns that demonized individuals with alcohol use disorder as “inebriates”, or that those who “take the first drink…that leads to ruin”.

Not only did these media campaigns lead to the probation of alcohol – a failed American experiment begun in 1919 – but also the proliferation of secretive, stigmatized, treatments for alcohol use disorder. These so called “inebriate asylums” were the result of a decades long campaign to discriminate against individuals that had a medical condition, what we now know to be a chronic disease of the brain appropriately labeled a severe substance use disorder.

Though the disease model has gained mainstream attention since 1956, when the American Medical Associated declared “alcoholism an illness”, and even further in 1987 when it was given the moniker of disease, it would appear that the mainstream media conglomerates and journalists have failed to learn the impact that their depictions of individuals with a substance use disorder has on the public and private treatment of human beings with a chronic disease.

The campaigns of the 1800 and 1900s have not stopped with our new understanding of substance use disorder, an understanding that is rooted in decades of empirical evidence. In truth, they have grown increasingly negative.

One only need to look to covers of Time Magazine, depicting “Crack Kids”, or the individual “hooked” on alcohol and other drugs – or perhaps to the parlance of “junkies”, “addicts” and “substance abusers” all too common in most journalist’s depiction of the modern day opioid epidemic.

We may not have inebriate asylums in the country anymore, but we still have a health care and criminal justice system that marginalizes and stigmatizes individuals with what we know to be a disease – in large part due to medias discriminatory portrayal.

Researchers have continued to sound the alarm at the potential harm this language and characterization of substance use disorder can have in real world settings. Medical professional’s delivery substandard care; a decrease in treatment and other help seeking behavior; mass criminalization of substance users; the myths of the “addicted baby” and the “Narcan Party” – all real-world outcomes that are linked to the way speak about individuals with a severe substance use disorder.

While journalists and media outlets are not the only cause of the country’s poor response, it is past time they take ownership of the role they do play. An extra 5 words of copy to state “a person with a substance use disorder” rather than “that junkie” goes a long way in bringing humanity back to a discriminated against group of Americans – a community that is estimated to be over 23 million large. It may not solve the opioid crisis or any future substance use crisis this country is likely to have; but it will make a difference.”

Let’s all try to be part of the solution and not part of the problem when we talk about our family members, friends or anyone struggling with substance use issues. Language matters. Changing it does not cost a dime but has a long term positive impact.

Here is a resources that that has an easy to read graphic(Say This, Not That) on ways you can change how you talk about addiction.

April 30, 2018

Surgery and Addiction: Dangerous Bedfellows

I am regularly asked about dealing with surgical procedures that require pain medication while also being in long term recovery from substance use.

Having to undergo surgery while dealing with such issues can present challenges. It doesn’t matter if the surgery is major or minor, postoperative pain must be managed.

For years, doctors told me that at some point, I would need a full right hip replacement. Since I was relatively young for such a diagnosis, I put it off as long as possible, managing pain through anti-inflammatory steroid injections and non-narcotic pain meds. It however, got to the point where I was in excruciating pain on a regular basis, unable to sleep because of it. I could not put it off any longer. It was time for a new hip.

From a surgical standpoint, in addition to cocaine and alcohol, my history also involved misusing prescription pain medications when I could get my hands on them. Oxycontin and Hydrocodone were among my favorites. I also misused black-market Xanax (in yet another classification of drugs called benzodiazepines, or “benzos”) and Ambien, a prescription sleep aid that many cocaine bingers know so well.

This history had to be taken into account in formulating my surgery recovery plan.

The key for me in approaching my hip replacement recovery was rigorous honesty, self-awareness and having a strong support system of friends, loved ones, caretakers and importantly, medical staff who knew about my past.

I also had to understand that even in long-term recovery, I could be susceptible to wanting that familiar “feeling” and cross the line from pain management into misuse which could then easily cascade into physical dependance and ultimately addiction.

I had to be meticulously upfront and forthright with all those in the chain of treatment and support about my past and my concerns of how narcotic medication could affect me physically and mentally. I couldn’t hold back without risking my sobriety.

From the start, I told my surgeons I am a person in recovery from drug and alcohol issues. We then discussed what medication would be needed to manage the pain after the surgery. We agreed that my doctor would be prescribing me Percocet. We talked about how long other patients normally took it, the standard dosage, etc.

I made it clear that post-op, I would not be allowed to self-administer narcotic pain medication. My girlfriend at the time(now wife) would dispense the meds. We also agreed that I was not to be allowed a refill without a face-to-face consultation with my doctor to discuss why I felt it was needed. The rule would always be to take the smallest dose possible to manage the pain and to eventually taper off to aspirin only.

Post surgery, I successfully tapered off from Percocet to Tylenol quickly with no adverse effects and no moments where I felt triggered to take more than the prescribed dosage. Every situation will be different, but there is one constant in a successful pain management program:

Honesty.

Honest with friends and loved ones. Honesty with doctors. Honesty with myself. Understanding my weaknesses and the level of support I needed to counteract those weaknesses.

Don’t be afraid of surgery because of an addiction past. Deal with the issues right up front and have a recovery plan that involves everyone in the chain. You can do it!

Brian Cuban (@bcuban) is The Addicted Lawyer . Brian is the author of the Amazon best-selling book, The Addicted Lawyer: Tales Of The Bar, Booze, Blow & Redemption (affiliate link). A graduate of the University of Pittsburgh School of Law, he somehow made it through as an alcoholic then added cocaine to his résumé as a practicing attorney. He went into recovery April 8, 2007. He left the practice of law and now writes and speaks on recovery topics, not only for the legal profession, but on recovery in general. He can be reached at brian@addictedlawyer.com .

April 22, 2018

She Went From A Federal Prison Inmate To Yoga Recovery Lawyer

I recently had the honor of telling my story at the three Minneapolis/St. Paul law schools. During that visit, I met attorney Suzula Bidon. Suzula has a journey that personifies redemption: Addiction; federal prison; the battle as a convicted felon to get her law license; a certified yoga instructor; a story worth reading and learning from.

Brian Cuban: Where have you been in life?

Suzula Bidon: I started in the woods in northwest Wisconsin, on the Yellow River. I was an only child of hippie parents catching frogs and tadpoles until my brother came along when I was five. I was largely isolated from the world. I had little regular, consistent social interaction, and little interaction with community.

When I think about that time, and the role it played in my susceptibility to addiction, I think of the Rat Park experiment. In the late 1970s, researchers were studying addiction by giving rats in cages two choices of water: one with drugs, one without. Most rats drank the drug water and died. Then, one of the researchers had a thought: of course rats alone in a cage with nothing to do and no other rats for companionship would choose the drugs. What would happen if they tried the same experiment in a social, resource-rich environment with toys, and other rats, and room to run around? Well, the results in Rat Park were different. Most rats did not choose the drug water. While there are many factors, I believe my isolation during my childhood is part of what set me up to be susceptible to addiction.

When I started school, it was like being thrown into the deep end of the social pool, without social skills. I felt hypersensitive and socially awkward, so by the time the gateway drugs (cigarettes and alcohol) became a part of the scene in middle school, I was thrilled to have a way to fit in and quell my social anxiety.

Suzula Bidon

After my sophomore year in high school, we moved to a city, St. Paul, MN. Shortly after the move, my father died of a heart attack. I was dealing with the upheaval of moving, a whole new level of social anxiety, and profound grief and loss. I managed to finish high school at a prestigious prep school, St. Paul Academy, which got me into Barnard College in New York. That’s when my addiction really took off.

I tried everything, got addicted to heroin, got off heroin with methadone, graduated from college on methadone, and then when I got off methadone, I started using stimulants (methamphetamine and cocaine). For me it was never about the effects of a certain drug; it was about control – having a way, a pill or a powder I could take, to change the way I felt.

In New York, I struggled, in and out of sobriety, and during one of my sober stints I was randomly attacked on the street one morning. I was lucky — I wasn’t permanently injured, just beat up — but it scared me enough to move back to Minnesota.

In Minnesota, I white-knuckled it for five months, but I wasn’t done using drugs. I still felt uncomfortable in my own skin. I started using methamphetamine and then selling small amounts to support my own drug use. When a drug buddy in New York found out I was selling, he asked me to send him some and I did – small amounts a handful of times. Then he asked me for a much larger amount, I sent it, and the package was intercepted. I was federally indicted on a conspiracy drug charge and ended up spending 30 months (27 with good time) in federal prison.

When I got out in 2009, I had three missions: to stay sober, build an amazing life in recovery, and to become a lawyer so that I could change the system. I paid my dues working for $7.25 an hour at a bagel shop, got into law school, and started in 2011.

I loved law school, and graduated magna cum laude in 2014. The Board of Law Examiners put me through hell, but eventually they gave me a license in 2015. After a year of criminal defense, I ran a nonprofit for six months, and since then I’ve been working as a solo, and a policy consultant.

BC: Where are you in life now?

SB: Law has taken a back seat for me these days. My main focus is yoga. In 2011, I felt something was missing from my recovery. All the outward signs were good, and my recovery was going strong. I was involved in 12-Step fellowships, I was doing service, I was in law school. I was still uncomfortable in my own skin. It dawned on me that what was missing was a physical component. There’s a great saying, “we store our issues in our tissues,” and until that point I had done little to reconcile and reconnect with my body. I was thinking recovery, but I wasn’t living and breathing recovery.

I got certified to teach yoga, and I created a yoga curriculum specifically for addiction recovery, that eventually became Recovery Yoga Meetings®. Now I’m scaling that business to hopefully become the industry standard for yoga as a complementary treatment for addiction in healthcare. I’ve created a teacher training curriculum, and it just keeps growing. I’m also a writer. I’m working on a memoir and a recovery guide that incorporates all the tools and skills I’ve learned along the way.

BC: What is your hope for the future and message to others?

SB: We as a profession, as a society, as a country, have got to rise together to meet this challenge of addiction. And a big part of that is having the courage to make an objective, rational assessment of how our policies are working. The Drug War and mass incarceration are failures by every definition. There are more drugs, more easily available, and more people are dying than ever before. It’s like we learned nothing from Prohibition. And we need to once and for all treat addiction as the public health issue it is. My personal belief is that addiction is an illegal disease.

One of the things I do is present continuing legal education seminars on addiction-related law and policy. Lately, I’ve been sharing five simple changes to the way we talk about addiction.

First of all, “stigma.” That’s the layperson’s term for what we call discrimination. Whether we’re talking literally, under the ADA, or more generally in terms of the collateral consequences of addiction, we have got to stop soft-pedaling this. If a person is in established recovery from addiction, it is discrimination to hold their past against them.

Second, “addiction” itself. Addiction is the most severe form of substance use disorder, which is a spectrum, according to the DSM-V. There is substance use, substance misuse, substance abuse, and finally full-blown addiction. Eighty to ninety percent of individuals who use substances do not develop a problem. Not everyone with a substance use problem has addiction.

Third, “addict” and “alcoholic.” This one is long overdue. We need person-first language. We don’t call people with cancer cancerians. Or someone with depression a depressive. I am a person in recovery from substance use disorder. Historically, 78 years ago when the medical field didn’t understand addiction, and everyone thought it was a willpower or moral issue, people who couldn’t stop drinking starting meeting in rooms to support each other. They identified themselves as “alcoholics” for two reasons: to admit they had a problem, and to identify with each other.

Twelve-Step programs, mutual aid societies, and peer support services are still valuable tools for healing, but we have conclusive scientific evidence that demonstrates that substance use disorder is a brain disorder. In the legal profession and society at large we need to demonstrate our understanding by using accurate and non-judgmental nomenclature.

Fourth, “clean” and “dirty.” If you work in the criminal justice system you know what I’m talking about. It’s most common with regard to urinalysis for drug testing. If a test comes back positive for a substance, it’s dirty, and hence the client is dirty. No drugs, it’s clean, she or he is clean. Gee, there’s nothing pejorative about that. Again, let’s be professional and use the proper terminology: a drug test comes back positive or negative for the presence of substances. A client has been abstinent or not.

And finally, my personal favorite: Medication Assisted Therapy, sometimes referred to as Medication Assisted Treatment. We all think of this as methadone or Suboxone, for opioid use disorder. But think for a moment about smoking. Many people use a nicotine patch, or gum, or a medication to manage their cravings while they change their behavior, and stop smoking. The same principle applies when it comes to opioid use disorder. Studies show that medication assisted therapy leads to better outcomes for treating opioid use disorder. I am living proof. Medication assisted therapy, methadone in my case, saved my life. I tried abstinence repeatedly, and I couldn’t stop going back to heroin. The methadone dealt with the opioid receptors in my brain, by preventing cravings and withdrawal symptoms, so that I could change my habits. Methadone allowed me to get off heroin, and since I wasn’t spending my time buying illegal drugs, I was able to devote my time to rebuilding a life I actually wanted to live. I eventually graduated from Barnard while in MAT.

Still skeptical? The founders of Alcoholics Anonymous included in the AA basic text this quote by Herbert Spencer: “There is a principle which is a bar against all information, which is proof against all arguments, and which cannot fail to keep a man in everlasting ignorance — that principle is contempt prior to investigation.” Look at the evidence and see for yourself.

You can learn more about Suzula and Recovery Yoga Meetings® at recoveryyogameetings.com

Brian Cuban (@bcuban) is The Addicted Lawyer . Brian is the author of the Amazon best-selling book, The Addicted Lawyer: Tales Of The Bar, Booze, Blow & Redemption (affiliate link). A graduate of the University of Pittsburgh School of Law, he somehow made it through as an alcoholic then added cocaine to his résumé as a practicing attorney. He went into recovery April 8, 2007. He left the practice of law and now writes and speaks on recovery topics, not only for the legal profession, but on recovery in general. He can be reached at brian@addictedlawyer.com .

April 17, 2018

What Would You Say To Your High School Bullies?

Stories of childhood bullying are fairly commonplace. What is not commonplace however, is when someone confronts a bully, decades later in a very public setting.

That is what happened to Katy ISD Superintendent Lance Hindt. Mr. Hindt was confronted by someone he allegedly bullied severely in high school. The video has gone viral. Thousands have called for Mr. Hindt’s firing. Thousands have stood up in support of Mr. Hindt. Others have come forward to offer their stories corroborating that Hinds was in fact, a bully in high school.

Watching Greg Barrett recount the terrible physical assault he endured, brought up many painful memories for me regarding my time in the Mt Lebanon School District.

I was an “overweight” kid by societal norms at that time. I was often tormented over my weight by other kids. I remember their names and faces as if etched on a memorial to my suffering. Like Mr. Barret, I was also physically assaulted.

My older brother Mark had given me some gold, bell bottom disco pants. It was around the time the Saturday Night Fever movie and soundtrack came out so this style of clothes was not all that unusual among the disco set. The pants fit Mark fine but were tight on me but I wore them to school often. They were a symbol of the love of a person I idolized and wanted to be like. I was sometimes fat shamed when I wore them. I used self-deprecation about my body a a defense mechanism.

One day I was walking home with a group of who kids I desperately wanted to include me in their group. The began making fun of how the pants looked around my fat stomach. They physically assaulted me.

The kids began pulling at my pants tearing them. Then it was like wild dogs on a bone. The tore them off me completely and threw the remains out into a busy street, leaving me only in my shirt, underwear, shoes and socks. I gathered up the remains and used them to cover up my underwear for the long walk of shame home.

When I got home, I buried the remains of my pants at the bottom of the waste basket and told no one. I felt I could tell no one. I would lose my parents and brothers love and respect and validate how I felt about myself. Someone unlovable who was too weak to stand up to bullies. For years I compensated for that event dismissing it as just “kids being mean”. It was an assault.

I dragged the shame of that little boy through life like three tires attached to a chain and permanently affixed to my ankle. I was dragging it when like Mr. Barrett, I put a gun in my mouth in 2005. My first of two trips to a psychiatric facility. I dragged it through eating disorders, addiction and failed marriages. The shame was a gaping wound in my stomach that defined what I saw in the mirror as an adult before I finally began to allow that little boy to heal and learn to love himself in 2007.

In 2007, in addition to getting sober, I began therapy to tear back all the layers of my life and finally help that child. I talk to that child. I write letters to that child letting him know that the bullying was not about him. That he should not feel ashamed for keeping it to himself.

There were times during that process when I wanted to confront those kids and tell them what they did to me. I heard one of my bullies (not one of the ones who had assaulted me) had passed away and my only feeling was that he finally got what he deserved. Anger and hatred driving only me and not the bullies from decades before. I came to realize in therapy that it made no sense to hold on to that anger as it was destroying me.

In therapy, I found a place within me, as a middle aged adult to forgive those kids who tore my gold, bell bottomed discos pants off. I have no desire to cause them pain with stories who they were decades ago.

Does forgiving mean I have forgotten? Of course not. I could go to the spot within a few feet or so in Mt. Lebanon today and point out where the assault to place. Some trauma stays etched in the memory like a memorial to life-long pain. I could contact them on Facebook today and confront them. I won’t do it. I have no desire to do it. I have forgiven them. I continue working on forgiving that teenage Brian for feeling like he had no choice but to feel like he did not matter. He did matter. He was enough.

My journey is clearly different than that of Greg Barrett. It is not my place to tell anyone whether they should forgive and what that word should mean to them. If any of my bullies were in a place of authority over children like Mr. Hindt, I can’t say that I would not do exactly what Mr. Barret did. His journey belongs to him. I however, do have something to say to him.

Mr. Barrett:

My heart aches for you and that little boy who had no one to stand up for him. While our stories have differences, I know what it’s like to carry that little hurt, bullied little boy through life. Regardless of what ultimately happens to Superintendent Hind, I am glad you and that boy finally had a voice. It’s not just a voice for you but a voice for all those hidden bullied little boys and girls wanting to find their voice as well however they define that. Hopefully a healing voice. I wish you all the best in that journey.

Brian Cuban (@bcuban) is The Addicted Lawyer . Brian is the author of the Amazon best-selling book, The Addicted Lawyer: Tales Of The Bar, Booze, Blow & Redemption (affiliate link). A graduate of the University of Pittsburgh School of Law, he somehow made it through as an alcoholic then added cocaine to his résumé as a practicing attorney. He went into recovery April 8, 2007. He left the practice of law and now writes and speaks on recovery topics, not only for the legal profession, but on recovery in general. He can be reached at brian@addictedlawyer.com .