K.M. Alexander's Blog, page 44

April 28, 2018

Ghosts of April

It’s strange to me that in a few days April 2018 will have come and gone and we’ll be moving towards summer here in Seattle. Time—as ever—ticks forward. I realize that for the last few months, April in particular, things have been rather quiet around here. Damn near ghostly, in fact; so I wanted to take a moment to update everyone on what’s been happening.

I’m still hard at work on rewrites and edits for Coal Belly. That seems to be my usual state of being lately. Edits tend to be difficult for me, namely because my eyes see what my brain wanted and not what should be there. Thank goodness for copy editors. That said, it’s coming along at quite a clip, and I’ll be reaching out to my beta readers this summer. Then, once I get their feedback, I go back through it all over again.

The fourth Bell Forging Cycle novel has been in the works for some time now. While there hasn’t been any prose written, I do have a rough outline, and think I know where I want it to go. Now, whether Wal behaves is another matter. So often we writers create characters and then the characters do something wildly different than what we planned. It’ll be interesting going back to it after having written two very different books in the interim.

So that’s been my spring. It’s odd writing posts like these, because while a lot has been happening, it doesn’t always come across that way when you lay everything out. Once that progress slider is full it seems like everything should be done, but in truth, the first draft is only the beginning.

Okay, back to work.

April 12, 2018

The Wreckage of Men

“It is the nature of the artist to mind excessively what is said about him. Literature is strewn with the wreckage of men who have minded beyond reason the opinions of others.”

Sorry for the lack of updates. I’ve been quite busy deep in the manuscript mines these past weeks. That said, I have seen progress (yay!), and the proverbial light at the end of the tunnel is shining brighter. I’ll have more to share soon.

March 23, 2018

My Virtual Nightstand

The other day, I was chatting with a few friends, and we were talking about our to-read stack. We all have them, the books you’ve purchased queued up to read in no particular order. For some, it sits on our nightstand. For others, it’s on a shelf. These days it might be a collection of files on your Kindle. Voracious readers all have them—myself included.

As we talked, I realized I didn’t have a good way for me to track my own to-read stack. Afterall, while I do read primarily on my Kindle, I have a lot of physical books as well. My to-read stack was all over the place! Knowing what I have and what I could start next was a tad cumbersome.

But, I think I’ve come up with a solution. I’ve decided to start using Goodreads’ “To-Read” feature to list my collection of owned but unread books. This way, when I finish a book, I have one spot where I can peruse everything I have on hand. Since the list is public, I figured a quick post was necessary to explain how I’m using it. (I track books I intend to purchase with a different method.) These aren’t just books I’m interested in, these are books I’ve committed to reading eventually.

There’s no particular order, but feel free to check it out my list below. Maybe you’ll find something in my to-read stack that’ll pique your interest. Happy Reading!

K. M. Alexander’s To-Read List →

March 12, 2018

An ECCC 2018 Debriefing

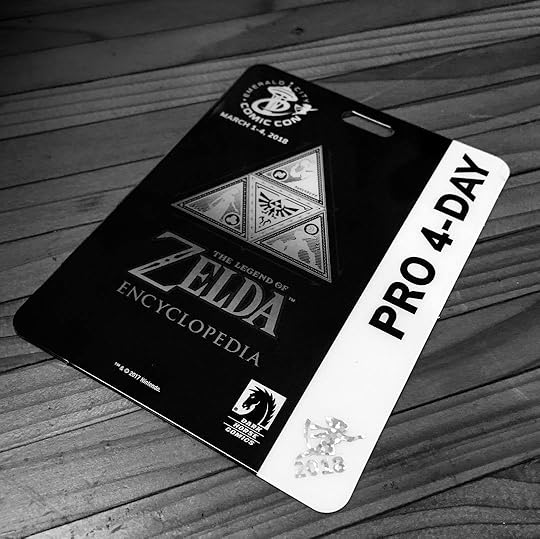

At the beginning of March (a few weekends ago, now) I joined ninety-five thousand others in attending Emerald City Comic Con in my hometown of Seattle, Washington. This year the convention was extended to four days—I skipped Thursday but visited Friday, Saturday, and most of Sunday. As is the tradition around here, it’s time for a convention debriefing.

March 10, 2018

Eight Writing Tips from Eight Different Writers

Over the last week, I saw a couple of authors share tips for writing and for whatever reason, they each chose eight as their number. I know there are others who go with more or less, some of which I’ve even highlighted on this blog (Elmore Leonard, Dave Farland, Heinlein.) I wondered if this was a thing, so I did a little Googling. I found quite a few sets so I figured it’d be fun to gather them up and share them here.

A note before we begin: take everything with a grain of salt. Glean what you can; ignore what doesn’t resonate. What works for one author doesn’t always work for someone else. There is no right path to writing. Be willing to try anything, and figure out your process along the way. It’s easy to get frustrated, but learn to enjoy the discovery, uncovering how you work is part of the fun. So, that said, let’s jump in!

[image error] 8 Writing Tips from Jeff VanderMeer

I really appreciate the candid nature of this advice. Unlike others, VanderMeer comes at writing from a very practical standpoint. It’s refreshing.

My Favorite: “Good habits create the conditions for your imagination to thrive.”

[image error] Kurt Vonnegut’s 8 Rules for Writing

If there were a “big eight,” it’d probably be these eight. (I’d theorize that it was Vonnegut who set the precedent.) He doesn’t hold back, and his “rules” clearly serve as guidelines for his razor-sharp prose.

My Favorite: “Be a sadist. No matter how sweet and innocent your leading characters, make awful things happen to them—in order that the reader may see what they are made of.”

[image error] Flannery O’Connor’s 8 Writing Tips

This set wasn’t assembled by O’Connor but rather gleaned from her work. However, it’s a fascinating insight into the way she worked and why her stories still resonate.

My Favorite: “I suppose I am not very severe criticizing other people’s manuscripts for several reasons, but first being that I don’t concern myself overly with meaning. This may be odd as I certainly believe a story has to have meaning, but the meaning in a story can’t be paraphrased and if it’s there it’s there, almost more as a physical than an intellectual fact.”

[image error] John Grisham’s 8 Do’s & Don’ts

There is a bit of an my-way-or-the-highway style to these “Do’s and Don’ts,” but there are some good approaches within them as well. And one cannot argue with Grisham’s results, but as always do what works for you—write to serve the story.

My Favorite: “Don’t — Keep A Thesaurus Within Reaching Distance”

[image error] Neil Gaiman’s 8 Rules of Writing

Gaiman’s rules are as varied and profound as his own work. But they also come from a place of kindness and empathy. Very much worth a read.

My Favorite: “Remember: when people tell you something’s wrong or doesn’t work for them, they are almost always right. When they tell you exactly what they think is wrong and how to fix it, they are almost always wrong.”

[image error] J.K. Rowling’s 8 Rules of Writing

This collection was gleaned from Rowling’s various quotes, and she offers some good advice for those struggling through the difficulties of creation.

My Favorite: “I always advise children who ask me for tips on being a writer to read as much as they possibly can. Jane Austen gave a young friend the same advice, so I’m in good company there.”

But wait… even after you read those rules, I should stress that Rowling didn’t assemble these herself. Like O’Connor above, someone else gathered them from various quotes of hers. However, unlike O’Connor, Rowling was able to hit up Twitter and explain her approach.

All nonsense. I’m with W. Somerset Maugham: “There are three rules for writing a novel. Unfortunately, no one knows what they are.” pic.twitter.com/V8JSHteiHz

— J.K. Rowling (@jk_rowling) November 9, 2017

While the post is absolutely a collection of things she said, they aren’t hard and fast “rules”—think of them as tips or approaches. As I mentioned above, there are no rules specific to everyone and Rowling would agree. You can read more of her thoughts on writing (pulled from Twitter), right over here.

Charlie Jane Anders’ 8 Unstoppable Rules For Writing Killer Short Stories

Personally, I’ve never been interested in writing short stories. But they are a staple of science fiction and fantasy. These eight little rules are a wonderful approach and would be effective for any fiction long or short.

My Favorite: “Fuck your characters up. A little.”

[image error] 8 Writing Tips from C. S. Lewis

Lewis’s tips are very similar to most modern writing advice. Just replace the “radio” with “internet” and magazines with the “internet.” Basically, replace the internet with books, people! Get rid of the internet!

My Favorite: “Read good books and avoid most magazines.”

So that’s it! Perhaps yo—

https://kmalexander.files.wordpress.com/2018/03/record-scratch.wav

Wait, though… if the J. K. Rowling’s “rules” weren’t really hers, right? I mean she said them, sure, but they weren’t her rules per say. (The same argument could be made for O’Conner and Lewis, but they’re not around to tell us any different.) That means I owe you someone else! So, here’s eight different rules from eight different authors—they also happened to have won the Nobel Prize for Literature.

[image error] 8 Writing Tips from Authors Who Won the Nobel Prize for Literature

As you’d expect, there’s a ton of good advice on this list. One thing I’ve noticed as you read more and more of these is that the tips and rules seem to the echo the others—almost as if each set is constructed of similar material but reflected by an inner mirror within each writer.

My Favorite: Alice Munroe’s “Work stories out in your head when you can’t write.”

So, there are eight writing tips from eight different writers writing tips from sixteen different writers! A lot of good stuff, and plenty of interesting strategies. Hopefully, you find something that works for you. I listed my favorites, but I am sure you have your own as well. What stood out to you? Anything you disagree with? Do you have your own list of eight? Leave a comment and let me know!

March 1, 2018

ECCC Starts Today—Let’s Hang Out

Today is the start of Emerald City Comic Con, Seattle’s premiere comic convention. It’ll run through Sunday, and it’ll be busy. Last year there were 90k people in attendance, and I’m sure this year will be much the same. (When I last checked most tickets are sold out.)

I will be present—but I won’t be showing up until tomorrow morning. I plan on being around Friday, Saturday, and Sunday. I’m not paneling or running a table so there’s no specific place you’ll see me, but I’ll be exploring everything. I expect to be hitting up a lot of the fiction panels—there’s quite a few that have piqued my interest. So keep an eye out, and don’t hesitate to say hello. We can high-five and stuff.

If you want to keep track of where I am, I recommend two places:

Twitter: @KM_Alexander

While I’ve decreased my tweeting over the last year, this is when it’ll be convenient. Odds are I’ll be using Twitter a lot, sharing what it is I see and hear.

Instagram: @kmalexander

As I take photos, I generally like to share them here. So if you enjoy black and white photography, and you’re interested in seeing whatever it is I find exciting I recommend following me here.

I hope everyone has a fun, safe, healthy, and respectful convention. Should be a great time and I’m looking forward to seeing everyone.

February 28, 2018

Fantasy As A Challenge

“When people dis fantasy—mainstream readers and SF readers alike—they are almost always talking about one sub-genre of fantastic literature. They are talking about Tolkien, and Tolkien’s innumerable heirs. Call it ‘epic’, or ‘high’, or ‘genre’ fantasy, this is what fantasy has come to mean. Which is misleading as well as unfortunate.

Tolkien is the wen on the arse of fantasy literature. His oeuvre is massive and contagious—you can’t ignore it, so don’t even try. The best you can do is consciously try to lance the boil. And there’s a lot to dislike—his cod-Wagnerian pomposity, his boys-own-adventure glorying in war, his small-minded and reactionary love for hierarchical status-quos, his belief in absolute morality that blurs moral and political complexity. Tolkien’s clichés—elves ‘n’ dwarfs ‘n’ magic rings—have spread like viruses. He wrote that the function of fantasy was ‘consolation’, thereby making it an article of policy that a fantasy writer should mollycoddle the reader.

That is a revolting idea, and one, thankfully, that plenty of fantasists have ignored. From the Surrealists through the pulps—via Mervyn Peake and Mikhael Bulgakov and Stefan Grabiński and Bruno Schulz and Michael Moorcock and M. John Harrison and I could go on—the best writers have used the fantastic aesthetic precisely to challenge, to alienate, to subvert and undermine expectations.

Of course I’m not saying that any fan of Tolkien is no friend of mine—that would cut my social circle considerably. Nor would I claim that it’s impossible to write a good fantasy book with elves and dwarfs in it—Michael Swanwick’s superb IRON DRAGON’S DAUGHTER gives the lie to that. But given that the pleasure of fantasy is supposed to be in its limitless creativity, why not try to come up with some different themes, as well as unconventional monsters? Why not use fantasy to challenge social and aesthetic lies?

Thankfully, the alternative tradition of fantasy has never died. And it’s getting stronger. Chris Wooding, Michael Swanwick, Mary Gentle, Paul di Filippo, Jeff VanderMeer, and many others, are all producing works based on fantasy’s radicalism. Where traditional fantasy has been rural and bucolic, this is often urban, and frequently brutal. Characters are more than cardboard cutouts, and they’re not defined by race or sex. Things are gritty and tricky, just as in real life. This is fantasy not as comfort-food, but as challenge.

The critic Gabe Chouinard has said that we’re entering a new period, a renaissance in the creative radicalism of fantasy that hasn’t been seen since the New Wave of the sixties and seventies, and in echo of which he has christened the Next Wave. I don’t know if he’s right, but I’m excited. This is a radical literature. It’s the literature we most deserve.”

I don’t usually post quotes this long, but as I’ve been working on Coal Belly, and after publishing my essay on problematic fiction this quote from 2002 has been kicking around in my head. (Originally from here, but it’s been modified over the years.)

My work has frequently been described as “difficult to categorize”—and while I label the Bell Forging Cycle as urban fantasy for simplicity, it’s no secret that its more accurate description is much more complicated. I revel in this, genre classification is boring at best and writing dangerous or challenging fiction within the “Next Wave” the “New Weird” or whatever we want to call it is exactly where I want to be as a writer.

February 20, 2018

Okay, Who Is Doing This?

Someone has been sending me mysterious gifts, and I have no idea who’s doing it.

There is a reason they’re doing this: I don’t like birthdays. I have no problem with them as a concept, and I don’t mind getting old. My argument against them is curmudgeonly, and I’m sure rooted in my disdain for Facebook (and what it’s done to birthdays.) As a result, I usually keep my birth date to myself which means most of my friends are always trying to guess when it’s my birthday. Which has now led to strange packages arriving willy-nilly.

Several months back—someone, I have no idea who—randomly sent me Judith Schalansky’s amazing Atlas of Remote Islands and with it came a note saying it was a gift for my birthday—whenever it happened to be—I posted about it on Instagram. To this day I don’t know who sent it, and Kari-Lise (who seems to know) isn’t telling.

[image error]The mystery gifts and notes

Fast forward to this weekend. We returned home from the opening of Kari-Lise’s show in Portland, and a curious little box was waiting for us and addressed to me. Inside was Werner’s Nomenclature of Colours, and it came with a note that read:

It is not your birthday. There is nothing here for you.

Okaaaay… that’s a touch mysterious. To add to the puzzle, the box was empty, but it still felt heavy. It didn’t take long for me to realize the package had a false bottom, so I flipped it over and broke the seal on the bottom. There I found another compartment, and inside was another book, Charles Pierce LeWarne’s Utopias on the Puget Sound 1885-1915—an examination of five historical communitarian settlements that once existed locally. It also came with a note, and that note bore a single word:

#Resist

[image error]The second mystery book in its little compartment

The box came from the “DLB-Reinforcement Div” the return address pointed to Des Moines, Washington—a small city south of Seattle. When I searched for the address, I got nowhere. It didn’t seem to exist. This wasn’t entirely unexpected, the first box I received had a return address that pointed to a non-address as well. Strange yes, but also quite compelling.

[image error]The mysterious non-address

So, the mystery remains! I have no idea who sent this pair of books. Both books look amazing. I can see how the Werner book will come in handy during my writing and the utopia book sounds fascinating. I knew we had a history of communes here in the Pacific Northwest. I didn’t realize how deep that history goes. I do appreciate these gifts.

Thank you, whoever you are.

February 16, 2018

I’m Going to ECCC

In a few weeks, I’m going to be attending Emerald City Comicon 2018 here in Seattle. But, this won’t be my typical “Come See Me At [Con Name Here] Post” only because this will be a bit different from my other appearances. While I will be attending ECCC as a pro, as of right now, I won’t be on any panels, and I’m not running a table. Instead, I’ll be paling around with my friend and fellow author Steve Toutonghi, and taking my time to enjoy ECCC. The plan is to reconnect with some friends, sit in on a few panels, maybe hit up the show floor, and do some networking.

If you’re attending, let me know! I’d happily meet up with any readers, and I’ve love to chat with you. If you see me out and about, please stop me and say hello! I’m as much a fan as I am a writer and I love talking with readers and fellow fans. I’m really looking forward to the convention, it’s been years (eight?) since I’ve attended ECCC and I can’t wait to lose myself in the craziness for a few days.

ECCC runs March 1st–4th at the Washington State Convention Center here in Seattle. You can find out way more info over on the official site. As of this post, there are still tickets available for Thursday and Friday. But they’ll go fast, so don’t wait.

Should be a good time. I hope to see you there!

February 13, 2018

The Poisoned Garden

This weekend, Kari-Lise and I will head to Portland, Oregon for the opening of VEILS at Talon Gallery where Kari-Lise will be debuting the first five pieces from her 2018 series, The Poisoned Garden. The show opens on Saturday, February 17th, and we’ll both be in attendance. If you live in Portland or the surrounding area come on by and say hello. We’d love to see you. The opening reception is from 6pm–9pm. The exhibition will be on display through March 12th, 2017, and it is both free and open to the public.

I’m so stoked this is finally reaching the public. There is a narrative aspect to The Poisoned Garden that really draws me in as a storyteller, and the series is shaping up to be a favorite. Kari-Lise is really throwing herself into the work, and it shows. Afterwards, you’ll be able to view all the pieces at Talon Gallery’s website, feel free to contact the gallery directly to inquire about any particular piece. I’m excited the initial debut of The Poisoned Garden is finally seeing the light of day.

[image error]Kari-Lise Alexander — “The Find” (Detail)

[image error]Kari-Lise Alexander — [Left] “Summer Dream” 10″x10″, Oil on Panel [Right] “Alone Amongst the Irises” in the studioThere are a few more pieces in this set that I’m not previewing here. To see them you’ll need to subscribe to Kari-Lise’s newsletter or come to the show. A collector’s preview is coming later this week, it’s easy to sign up: click here to subscribe.