Judith A. Yates's Blog, page 2

February 2, 2021

Our fascination with death (""Do we get to see dead bodies!")

While teaching Criminal Justice, I took my students on a field trip to the county morgue. I warned them to think about their questions before they asked. Just before the tour, the Medical Examiner asked, "Any questions?" One female student asked loudly, "Do we get to see dead bodies!" He merely stared at her. The other students were embarrassed. Why are so many people fascinated with death?

My students were always pleading for tours to The Body Farm and the morgue. They wanted to study death scene photos. But it isn't just my students. There are books and websites dedicated to crime scene photos. People slow down at car wrecks and stare at body bags.

Death is the greatest unknown. The space program now has pictures of mars. The United States sent people to the moon. We can supposedly find out about our past lives and futures and tell a lie from the truth. One dab of spit reveals a perpetrator or a great-great-great-great-grandfather and his country of origin. We live in a world where answers are seconds away, from baking a cake to the chemical elements of Osmium tetroxide.

We rely on faith to tell us where we go when we die: Heaven if we are holy, Hell if we are sinful. Depending on the religion, it is God or Allah or Buddha or - you get it. But we only know these things in faith. A dead body is tangible evidence of what happens to us and what we look like from the inside. There it is: spleen, stomach, brain, eye sockets.

And we are a nosy society. True crime shows. Reality shows. Magazine covers were featuring Princess Diana as she lay dying in the 1997 car crash. So many years ago, this would have been considered intrusive. Now it's everyone's business, including the gory details. And the gorier, the more impressive.

Society loves shock value. Count the number of true crime shows on television. The audience can follow along with the crime, making the adrenaline pump; the fear factor kicks in. We are moving from a mundane, predictable, boring life to something we cannot control for a few moments, something scary, a real-life horror film, real evil. And then we look at the perpetrator and see they could be the person next door, in the next office. Even scarier!

Now back to that Criminal Justice class. My class did not see dead bodies that night's tour but watched autopsies on video, and a third of the students almost lost their lunch. About a week after that field trip, a horrible house fire broke out in a local neighborhood and killed the girl who had blurted out, "Do we get to see dead bodies!" We learned the fire trapped her in a bedroom, and she burned to death. The next time I saw the Medical Examiner, I told him about it. "Oh," he said sadly. "That was an awful (autopsy) to do. That poor girl..." He grimaced in sadness and horror.

Unfortunately, she got to see a dead body, a lot of them surrounding her own.

Image:This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

January 23, 2021

With Very Special Guest Star… Inmate # 145324

There is a barrage of “reality” shows on television with a new lineup of “reality” stars who wear orange jumpsuits or black-and-white stripes. And I’m wondering if this is such a good idea.

There is a show called “60 Days In” where you, too, can be an inmate without committing a single crime. Law-abiding folks are admitted into jail as covert spies for the sheriff, reporting everything from crooked staff to drug smuggling. It follows a pattern: there’s the clueless, nice person, the intellect, the jerk, and the person who “turns” (a Stockholm Syndrome of sorts). Then there is a show that follows inmates around with cameras, with a soundtrack, where we can watch them show out, shout down toilets, and talk about “getting out and staying out” of jail. Next, we can always tune into “Lockup” (much of the same), “The World’s Worst Prisons,” where the host tells us gravely he is “locked in alone” with “murderers, rapists, and thieves” (but along with a camera crew). A viewer can go to prison from the La-Z-Boy’s safety while getting pizza rolls and a beer in between shows.

The New "Reality TV" Star

The New "Reality TV" StarHaving worked in custody from jail to maximum psych wards, I know that only the noteworthy make the show: the contraband, fights, bad cops, emergencies. The larger percent – counts, chow hall, work details, inmate’s minor, consistent complaints – end up on cutting room floors. (Who wants to watch an officer have a patient discussion with a grown adult regarding the inmate cleaning his room?) Like all “reality” shows, going behind bars is there to entertain first with reality succeeding.

These shows make jail and prison appear enjoyable, and doing time as easy to do. Inmates getting their hair braided and watching TV all day, weight room workouts, armloads of junk food (commissary) make incarceration a great alternative to life on the street.

These “behind bars” shows create stars out of serial criminals, “the worst of the worst,” as the announcer likes to say. Always with booming background music and various camera angles, using the inmate’s jailhouse name, letting them ramble about just what a badass they are and how many bullets and blades they’ve outlived. The new entertainers have names like “Cut” with blue stars tattooed across their faces and doing twenty to life for rape. I can bet once the show airs, their mailboxes are full of fan mail.

The shows never focus on prison rape, PTSD of brutal stabbings and beatings, the raw fear, and lack of resources to escape the vicious cycle of recidivism. The viewer never goes beyond that dark curtain where tears flow at night, loneliness and despair of wishing life had turned better, somewhere, different choices made. The constant mistrust and visceral survival mode of incarceration both glossed over.

Thus, my concern. For too many young people, incarceration is a rite of passage or part of life. For young men in specific environments, machismo is essential. One dynamic in female gangs is proving females are harder than males. These kids see these shows as “reality”: enjoyable, doing time is easy, where they can be “stars.” And for kids or young adults desperately seeking power, or the fear of incarceration being the sole reason for avoiding crime, “reality prison TV” opens a path.

Television viewers have gone a step beyond the Osbornes, the Kardashians, housewives, the pregnant teens, and overweight gypsy little people; these are shows between that fine line of exploitation and (some) education - again - entertain first with reality succeeding. In my professional opinion, going into jails and prisons is an entirely different “reality” show. In reality, divorcing a 90-day fiancé or The Bachelor is easy. Doing time, not so much.

Photo: Inmate Name: ZEBRASKY, ALYSSA BREANNE 0064893 - Boardman PD

January 20, 2021

This Texas outlaw deserves a place in history

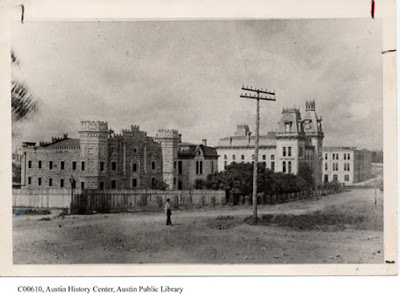

Travis County Jail, Austin, TX. circa 1800sJailer Nichols keyed open the door to allow Mrs. Boyce’s exit. He also allowed her husband to exit, for when he turned, Reuben was holding a six-shooter and pointing it at the jailer, demanding Nichols step back into the jail while Reuben stepped out. Staring down the business end of the gun, Nichols did as requested while handing over the keys.

Travis County Jail, Austin, TX. circa 1800sJailer Nichols keyed open the door to allow Mrs. Boyce’s exit. He also allowed her husband to exit, for when he turned, Reuben was holding a six-shooter and pointing it at the jailer, demanding Nichols step back into the jail while Reuben stepped out. Staring down the business end of the gun, Nichols did as requested while handing over the keys. Outside stood Reuben Boyce’s horse, saddled and bridled. It did not take long for Boyce to be a dusty memory. Jail Officers and Texas Rangers pursued Boyce, but it was too late, and Reuben’s horse was too fast. In mid-January, an unnamed reporter in the Austin Weekly Statesman responded to a comment on the “carelessness” of “the Travis county jailer” made by an anonymous writer for the Express. The Statesman reporter noted the jail guards “ever vigilant,” and to deny visitation to inmates would be “cruelty” to both visitors and inmates. To suspect every person coming into a prison of wrongdoing would “lead to disgraceful surveillance or to brutality.” Boyce worked his way to Louisiana, back through Texas, and then to New Mexico, where he went to work in a mine. It was here where he shot and killed a man. A friend of the murdered man turned Boyce in by contacting U.S. Deputy Marshals. Thus, Boyce was arrested on June 10 by the marshals, and Austin sheriff’s deputies were notified. There was no jail in Socorro, so an officer had to guard Boyce. On July 14, as a Texas representative arrived in Socorro to take Boyce, the guard nodded off, and Boyce walked off, missing a trip to Texas. Days later, Indians raided Socorro. Officers chased the marauders into Bear Mountains, where they accidently discovered “Rube” Boyce hiding out. Once again, Boyce donned handcuffs. Boyce was 28 years old at the time. Now it was back to Austin. Settled back in the Texas capitol’s jail, “Rube” Boyce was interviewed by a reporter for the Austin-Weekly Statesman on December 21, 1881. Boyce explained the murder he committed in Llano county was in self-defense when a “half-breed Indian named Johnson” stole horses, including Boyce’s mount. When Boyce attempted to reclaim the horses, Johnson pulled a pistol, and Boyce had to shoot him. Boyce then explained he committed the second murder in 1877 in Kimble county, during a dispute with his brother-in-law R.F. Anderson “over a yoke of cattle.” Again, he claimed self-defense. Boyce was also innocent of the Pegleg stage robbery as he was nowhere near the crime scene, and those who accused him were scallywags. When asked why he escaped from the Travis county jail if he was so confident in his innocence, Boyce reportedly replied he wished to “breath the pure air, and enjoy God’s glorious sunshine, undimmed by the foul dismal shadow of a prison’s bars.” He then gave the reporter money to return with tobacco and matches. During “Rube” Boyce’s 1882 trial, the judge discovered U.S. Marshals had tampered with two jurors. Deputy Marshals McFarland and Burleson were observed walking with two jurors and speaking with jurors privately. A marshal denied a juror tobacco as “it was the right thing to starve him into a verdict.” Jurors were allowed whisky, and strangers could walk in and out of the jury room. Juror’s wives would intervene during breaks, asking their husbands to just vote guilty and come home. The judge granted a new trial. Eventually, Reuben “Rube” Hornsby would walk. Even after this chance to do right, Boyce could not stay out of jail. On April 20, 1882, a short paragraph in the Brenham Weekly Banner noted he had been arrested for cattle rustling. And finally, a one-sentence notation in a November 30, 1890, Texas newspaper: “the notorious Rube Boyce killed in Sutton county.” Not much published of the outlaw’s death except a bullet found him in Sonora, Sutton County, Texas, and always the articles referred to his Austin jailbreak.

* Sometimes written as Peg Leg Resources Escaped from jail. (1880, Jan. 06). Austin-American Statesman. Austin, Texas. Escaping Prisoners and the officers. (1880, Jan. 15). Austin-Weekly Statesman. Austin, Texas. Fatally Shot. (1890, December 1). Memphis Daily Commercial, Memphis, Tennessee. Legends of America Old West Outlaws. https://www.legendsofamerica.com/outl... Rube Boyce Interviewed. (1881, Dec. 22). Austin-Weekly Statesman. Austin, Texas.Rube Boyce Fatally Shot. (1890, December 6). The Purcell Register. Purcell, Oklahoma. The Rube Boyce Case. (1882, March 2). Austin-Weekly Statesman. Austin, Texas. Throw up your hands. (1879, April 17). Wayne County Herald. Honesdale, Pennsylvania. State News Section (1882, April 20). Brenham Weekly Banner. Brenham, Texas. Summary of the news. (1890, November 30). The Galveston Daily News. Galveston, Texas. Photo: C00610, Austin History Center, Austin Public Library

December 28, 2020

The Bandit Queen: from Mud Hole to Millions

The well-dressed woman parked in front of the Boca Del Mar mansion and strode up to the front door with purpose. Anyone who glanced at her from the manicured lawns of one of Florida’s most expensive gated communities would believe her to be a high-profile real estate agent or perhaps a stockbroker. They would not give her a second glance, but they should have because in less than two minutes, the woman would be driving away, her car packed with every expensive item the homeowner possessed. The woman’s name was Judy Amar, and she was not a well-heeled society member. She was a professional burglar, responsible for up to 500 home burglaries in one county for five years. It earned her the moniker “The Bandit Queen.”

Born in the mid-1940s, Judy Amar grew up on “Mud Hole,” a sharecropper’s farm in Vilonia, Arkansas (population 250). As soon as she could drag a bag, she was picking cotton at 3 cents a pound. It was drudgery and a never-ending cycle of struggle: to pay bills, to eat, to live. By 13, she was “the pretty girl,” wearing a 36C bra, and boys were tagging behind her. Judy was an unwed teen mom and lived by an ongoing mantra of “you’re ugly, and no one would want you” regardless of her adult-sized body. $29 a month was not going to buy beautiful things. Now she was poor and "damaged goods." She dumped her son on her parents and fled to Miami, Florida, where the 1980s advertised endless sunshine and good times. The only work she could find was prostitution. From there, addiction. From a frying pan into a hot, humid, sandy fire.

It seemed destitute followed her. Judy hooked up with a career burglar, but “he wasn’t very good at it,” she’d say later. He had her drive through the exclusive gated communities of Florida’s Boca Raton and Boca Del Mar “because no one would suspect a woman.” He would scope out a house, and while Judy waited, he would break in. They were caught and arrested, but Judy’s charges were dropped for insufficient evidence. Men, Judy decided, were stupid about burglary. She was going to prove it.

Judy Amar's first mug shot. The charges were dropped for

Judy Amar's first mug shot. The charges were dropped for lack of evidence. From here she became "The Bandit Queen."

First, Judy Amar studied the Sunday real estate section “Parade of Homes” of the newspaper, where she learned about floor plans, specs, and burglar alarms. She purchased a variety of wigs. “Long, straight ones, short ones … blonde, an afro,” Judy would say in a later interview. She splurged on an expensive business suit. Next, she rented a nice car, paying in cash. It was the 1980s, before all of the security stipulations, and she could exchange cars every week or few days. She changed license plates. Now the Bandit Queen went to work to earn the title.

The Bandit Queen would burglarize homes only Monday to Friday between 10 a.m. and 3 p.m. Judy would locate the security or police officer guarding the area. She discreetly followed the car until the officer went on break. Then she drove into the high-dollar gated communities, nodding or waving at security officers, "like I belonged there," driving purposely to a home with a recessed door. The doorway was most important, given her m.o. If anyone was looking, they observed a well-dressed woman park at the mansion and stride up to the front door with purpose. If a knock or doorbell brought someone to the door, she would apologize, “I have the wrong house!” After moments of silence, Judy produced a 12” screwdriver, popped the lock, and walked in.

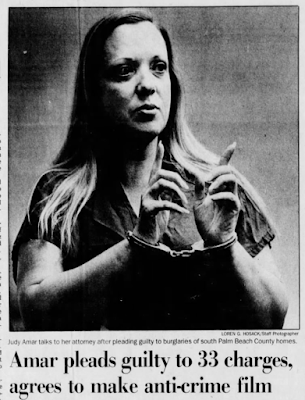

The Palm Beach Post (09-04-1987)

The Palm Beach Post (09-04-1987)

Alarms were no deterrent. Cops know 90% of home alarms are false. It would take the cops an average of ten minutes to arrive. Plenty of time to go to the master bedroom while pulling on gloves, grab a pillowcase, and rifle through jewelry. By now, Judy knew expensive jewelry from fake. She then went to closets for quality clothing: furs, name brand suits. And the Bandit Queen knew her Rembrandts from copies, a Remington from a local artist. If the car could hold it, she would make several trips. Sometimes Judy found family secrets hidden away: naughty photos, newspaper clippings of clandestine charges, drugs, hidden papers. As a joke, she would display them on the bed for law enforcement or the unsuspecting family to find. In 90 seconds, she was out the door. “It was,” she admits, “an exciting feeling.” She sold the goods or traded for cocaine.

Judy Amar would hit ten to twelve houses in a week, eventually amassing over six million dollars in art, jewelry, and clothing. In one haul, she stole $250,000 worth of goods. After committing the biggest home burglary spree in the United States, she was busted in June 1987. Judy’s hotel room looked like a “storage shed,” said one investigator, floor to ceiling with $45,000 worth of goods. Cops would recover $100,000 in items. She received a ten-year sentence, with a mandatory three years minimum. And Judy agreed to make an educational film for law enforcement on professional burglary. Judy never apologized to anyone. Instead, she blamed the homeowners for falsifying insurance claims.

“I stole illegally; they stole illegally,” The Bandit Queen said of her victims. “What’s the difference?”

Resources:

Borys, T. (2019, January 15) The harsh reality of home security systems and their response times. https://www.deepsentinel.com/blogs/ne...

Cone, T. (1987, December 29). Hot ice and cold cash. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archiv...

Sugarman, M. (Director). Lipsy, S. (Writer). Masterminds: The Bandit Queen (2004). Season 1, Episode 15.

Toplin, James H. (1987, September 30.) Boca-area burglar sentenced - woman gets 10 years in Boca Del Mar thefts. https://www.sun-sentinel.com/news/fl-...

December 11, 2020

Librarian mom intentionally ran over, killed by teens – how does this happen?

It began as a teenage romance gone sour. It ended in a gruesome murder of a beloved city figure. How did it get so far?

Polk City, Florida, is a small city where people know one another. As Sheriff Grady Judd said in a news conference, “there is not much crime.” So, the murder of Polk City’s Suzette Marie Penton, 52, was a double

punch to the city of less than 2,000. One service the little town offers is the Polk City Community Library. And working here was a librarian and lifelong resident Suzette Penton.

Suzette was one of those teachers every kid wishes they had. She made reading and learning fun for visiting students by dressing up as characters in the selected book. Suzette donned a “Cat in the Hat” costume to read a Dr. Seuss book. “Every kid in town loved Suzette because she’s just that type of person. She was just an outgoing, wonderful person,” a friend says. To support the local school, Suzette wore the school colors and face paint of a star and “#1.” She would put color streaks in her blonde hair. Everyone who knew her agreed she was a fun-loving person and a wonderful mom to Hunter.

Hunter was dating Kimberly Stone, 15. They broke up. Kimberly Stone threatened a “hit” six months later. She assured Hunter that her new boyfriend, Elijah Stansell, 18, would “handle it.” Elijah had never met Hunter. He was about to.

On November 9, 2020, Elijah borrowed the church van from where his father was a pastor. Kimberly joined him along with Raven Sutton, a big, hulking boy of 16, and Hannah Eubank, 14. They set surveillance across the street from the Penton home. When Suzette departed the house, Elijah, Raven, and Hannah went to the door and knocked. Hunter answered; the three burst into the home. Elijah blitz attacked with punches as Hunter vainly tried to protect himself. Raven reportedly got a few licks in. And Hannah stood by calmly, recording it all on her cellphone, as the family dog walked around. Unbeknownst to the attackers, it was all caught on video, both inside the home and outdoor security cameras.

And then Suzette Penton arrived home.

Elijah, Raven, and Hannah ran back to the van. Kimberly jumped out, with Elijah speaking to her as she stands, appearing nervous. The teens mill about; video captures them getting back into the van. Then it happened.

Suzette, angry mother and protector, storms over with her cellphone camera. She is taking photos of the van, of the driver. There were eyewitnesses. There was video. And there was Elijah, starting the van, jerking it into gear, then stomping the gas pedal and mowing down 52-year-old librarian Suzette Penton. “(Elijah) intentionally ran into, and over, her before fleeing,” the affidavit reads. “Three eyewitnesses … gave consistent accounts …there was no intent to maneuver around the victim … the driver … was malicious in his actions.”

Suzette Marie Penton was in the trauma intensive care unit before she died on November 25 from a skull fracture, intensive brain bleeding, aspiring fluid in her lungs, and injuries to her leg. Her family surrounded her.

Elijah, Raven, Hannah, and Kimberly are in custody. When cops told Kimberly Stone that Suzette had died, she retorted with a hateful remark, no remorse.

Another story of teens who never thought of what their action would lead to, and how one idea led to another until it ended in tragedy. How does this happen?

Teens live for the here and now. The juvenile brain is guided more by emotion and reaction, located in a section of the brain called the amygdala. The amygdala develops earlier than the frontal cortex, the area that controls reasoning and logic. The gang’s focus was on committing the crime and its immediate reward: beat up the kid, teach him a lesson. There was no thought past this task. There are no consequences of criminal behavior in the teen mind, including schoolyard bullying to murder.

This group leader was a young female, and female crime appears to be reactive; “violence among female youth can be a response to a broken or threatened relationship … offending may correspond to male partners’ influence” (Bright). We don’t know anything about Kimberly Stone’s life. Why was the relationship with Hunter so important to her? Why was adult Elijah Stansell dating a child and willing to commit a crime while she hid in the van? We do know that females are more cognitive in their actions than males. Males will act out physically while females will scheme. Juvenile males are more likely to hit or kick while females are more likely to traumatize emotionally. The male body is genetically engineered to be stronger, faster, while the female has survived on wits and cunning since the dawn of time.

After the crime, the child carries a cocoon of false safety because they live in the “here and now” and because of their emotional immaturity. How often has a parent stood over a child, wielding a broken item, asking, “did you break it?” (knowing the answer), with the child vehemently denying? “I’ll get away with it because I can fool them.” When finally presented with evidence, there is almost a “pretend” stage of “it didn’t happen” including “it was all a dream” (denial to self) or “I don’t want it to be real (taking it back) or “It wasn’t my fault” (blaming others). Notice the parallel to the Kubler-Ross stages of grief.

Logically, it is easy to understand how it all happened. Emotionally, as Sheriff Judd said in a press release, “I can’t even fathom teenagers doing something so heinous.”

Resources:

Affidavit Incident no. 200004376. November 9, 2020. Polk County Sheriff’s Office, Winter Haven, Florida. https://www.scribd.com/document/48403...

Bonvillian, C. (2020, November 12). Police: 4 Florida teens assault boy, run over librarian mother in attack stemming from breakup. https://www.boston25news.com/news/tre...

Bonvillian, C. (2020, December 4). Florida librarian run over by 4 teens in church van dies of her injuries; charge upgraded to murder.

https://www.kiro7.com/news/trending/f...

Bright, C., Johnson-Reid, M., & Kohl, P. (2014). Females In The Juvenile Justice System: Who Are They And How Do They Fare? Crime & Delinquency, 60(1).

Four teens arrested after intentionally running over Polk City woman. (2020, November 10). Press Release. Polk County Sheriff’s Office, Winter Haven, Florida. http://www.polksheriff.org/news-inves...

Obituary of Suzette Marie (Green) Penton https://www.legacy.com/obituaries/the...

Photo: City of Polk City

November 21, 2020

The bizarre crime of the oldest U.S. female inmate

Bart and Lucille had been close for about four years. Lucille had recovered from a heart attack, with Bart holding her hand and taking care of her during recovery. In return, Lucille purchased a car for Bart and paid his bills. It seemed like a fair arrangement until Bart started receiving his social security checks. According to Bart, Lucille wanted to be more than friends, so he told Lucille it was over. Lucille would later say she felt jilted. She had called Bart her “adopted son.” She felt Bart had taken advantage of her. Despite many in the senior housing complex feeling Bart was “a troublemaker,” other women gave Bart money, gifts. Now that she no longer gave him money, she thought he was ignoring her. On that Sunday, September 15, 2002, Lucille decided to show Bart how it felt to hurt. After morning church, she went home, set up afternoon donuts and coffee, then went to her room and pulled a box down from her closet: her late husband’s gun collection. She slipped a loaded .38 into her handbag. Lucille would later tell a reporter, “I said to myself, ‘If he’s just halfway decent to me, just halfway decent, I’ll take (the gun) upstairs.’” Bart’s “Good evening” sounded “arrogant.” Lucille followed behind him to pull the trigger. “Does it hurt?” Lucille demanded of the wounded Bart Flesche. “I really want it to hurt because you have hurt me so deeply, and I was so good to you. Do you realize every stitch of clothing that you have on your body - your glasses, your watch, the ring - I’ve even paid for your haircuts.” The horrified seniors watched the drama play out before Lucille seemed to realize what she had done and screamed for an ambulance. Upon arriving at the emergency room, medical personnel rushed Bart into surgery. The hospital would keep him for six days. Police arrived and Lucille was arrested without problems. Lucille would tell the police, “He looked at me like I was dirt.” She also said she shot him purposely in the lung because it would be “no big deal.”

Bart and Lucille had been close for about four years. Lucille had recovered from a heart attack, with Bart holding her hand and taking care of her during recovery. In return, Lucille purchased a car for Bart and paid his bills. It seemed like a fair arrangement until Bart started receiving his social security checks. According to Bart, Lucille wanted to be more than friends, so he told Lucille it was over. Lucille would later say she felt jilted. She had called Bart her “adopted son.” She felt Bart had taken advantage of her. Despite many in the senior housing complex feeling Bart was “a troublemaker,” other women gave Bart money, gifts. Now that she no longer gave him money, she thought he was ignoring her. On that Sunday, September 15, 2002, Lucille decided to show Bart how it felt to hurt. After morning church, she went home, set up afternoon donuts and coffee, then went to her room and pulled a box down from her closet: her late husband’s gun collection. She slipped a loaded .38 into her handbag. Lucille would later tell a reporter, “I said to myself, ‘If he’s just halfway decent to me, just halfway decent, I’ll take (the gun) upstairs.’” Bart’s “Good evening” sounded “arrogant.” Lucille followed behind him to pull the trigger. “Does it hurt?” Lucille demanded of the wounded Bart Flesche. “I really want it to hurt because you have hurt me so deeply, and I was so good to you. Do you realize every stitch of clothing that you have on your body - your glasses, your watch, the ring - I’ve even paid for your haircuts.” The horrified seniors watched the drama play out before Lucille seemed to realize what she had done and screamed for an ambulance. Upon arriving at the emergency room, medical personnel rushed Bart into surgery. The hospital would keep him for six days. Police arrived and Lucille was arrested without problems. Lucille would tell the police, “He looked at me like I was dirt.” She also said she shot him purposely in the lung because it would be “no big deal.” "The courtroom drama was as fascinating as the day of the crime."

The courtroom drama was as fascinating as the day of the crime. Records revealed Lucille had a restraining order filed against her by a male resident named Thomas (not his real name) in the senior high rise where she previously resided. Bart said Lucille confided in Bart about Thomas. “She waited in her car in the parking [lot] with her gun on two separate occasions; however, Thomas didn’t come home either day, and she eventually gave up.” According to Lucille, Bart, the self-described “missionary,” promised to “always” take care of her and “instructed her on what to do to get into heaven.” She said that Bart could be verbally abusive. When he started receiving his social security benefits and Lucille refused to sign her van over to Bart’s ministry “to God,” Bart began ignoring her. Soon, she was ostracized from his Bible study group. In turn, Bart Flesche told authorities that Lucille “was not interested in (my) ministry and in living Christian ways.” He began to avoid her. Lucille Mary Keppen pleaded to first-degree assault and sentenced to seven years. Initially, the court assigned her to the Whittier Psychiatric Nursing Home; records reveal she “was verbally aggressive, intolerant of others, and given to verbal outbursts” and she took herself off antidepressants that had improved her mood. Forensic evaluations recommended “monitoring of mood symptoms (and) issues related to relational instability, anger, and aggressive fantasy” although “Keppen is not apt to pose a high risk for future violent offending.” She was deemed remorseful, but only if it was in her best interest. Lucille was transferred to the Shakopee Correctional Facility in 2003 and began her sentence behind bars. While imprisoned, she required 24-hour attention due to her health. Lucille received her GED while incarcerated. She told a reporter that she lost everything – friends, home, money – but found the prison clean and comfortable. Still, she insisted Stephen “Bart” Flesche deserved to be behind bars while she should be free. Lucille Mary Keppen was released in 2007 on what would have been her late husband’s 104th birthday. She died in Minneapolis, Minnesota, in 2012, a month before her 98th birthday. Born May 29, 1914, she had outlived her husband, both sons, and was remembered as a storyteller. In the annals of criminal justice, she is recognized as the oldest female prisoner in the U.S. and possibly the world.

Resources: 10 Oldest Prisoners in the World. Oldest.org. Retrieved November 20, 2020 from https://www.oldest.org/people/prisoners/ Legacy Obituary for Lucille Mary Keppen retrieved November 19, 2020 from https://www.legacy.com/obituaries/sta... Minnesota’s oldest prison inmate, 93, released. (October 26, 2007). Associated Press. Retrieved November 20, 2020 from https://www.postbulletin.com/minnesot... Oldest and Youngest prisoners in U.S. History. (October 7, 2019). GlobalTel. Retrieved November 20, 2020 from https://blog.globaltel.com/oldest-and... Prison Life and Life After Prison. (2015) Sage Publications. Retrieved November 19, 2020 from https://www.sagepub.com/sites/default... State of Minnesota, Respondent, vs. Lucille Mary Keppen, Appellant. Minn. Stat. § 480 A. 08, subd. 3 (2002). Online: https://law.justia.com/cases/minnesot... Sullivan, L. (July 26, 2005). NPR Radio, “All Things Considered.” Woman, 91, Is Oldest Female Inmate. Host R. Siegel & M. Norris. Photo: ID 4580444 © Chrisharvey | Dreamstime.com

October 6, 2020

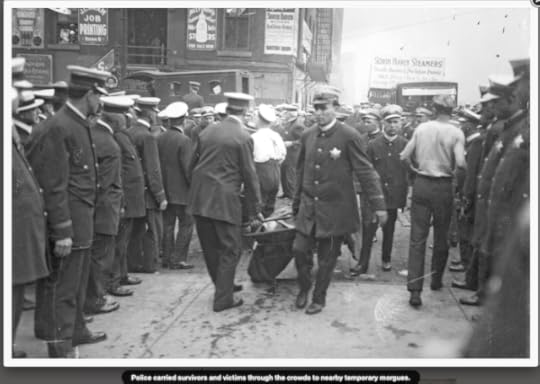

Chicago Police Officers and the sinking of the S.S. Eastland

On July 24-25, 1915, Chicago Police Officer Patrick Lally returned home from work, sank into his chair, and burst into tears. Officer Lally, soaked from both the drizzling rain and the Chicago River, had spent the weekend in rescue efforts. His family had never witnessed Lally shed one tear. Another police diver had broken down during his job, sobbing and screaming. And a fellow Chicago rescuer, a ship's Captain, would have horrific nightmares from that date. He took his experience silently to the grave. They were all involved in a massive rescue effort to save 2,752 passengers and crew from the sunken S.S. Eastland near the Clark Street Bridge, one of the worst maritime disasters in U.S. history.

The Eastland after capsizing, July 24, 1915

The Eastland after capsizing, July 24, 1915

The most extensive loss of life from a single shipwreck on the Great Lakes began as a wonderful day despite the weather. Hawthorne Works & Western Electric employees had a day off from their six-day workweek to attend the annual company picnic. Dressed resplendently and clutching their tickets, they boarded the S.S. Eastland early, unable to contain the excitement. The fancy liner would smoothly sail Lake Michigan to Michigan City, Indiana, for a day in the park. At 6:30 a.m., the passengers' animated sounds were filling the air hurrying up the gangplank for the best spot. At 7:30 a.m., the air filled with their screams for help and cries of the dying.

By 7:10 a.m., the ship was already listing away from the dock. The passengers' jabbering, most in their native language – the majority were Czechs – could be heard at the pier; it was only 20 feet away. The gangplank finally lifted at 7:18. The ship had settled to its rightful position. Five minutes later, the overcrowded Eastland listed again. Police officers on the dock noted the ship's change as they remained on scene, finished with passenger crowds. Officers witnessed the Eastland loll away from the pier, and it kept rolling. The excited jabbering became louder. The Eastland was falling as the Chicago River spilled into the portholes. Officers listened to the crash of pianos, furnishings, and various items down below. In minutes, all that remained of the Eastland was her great hull. She sank in 20 feet of water.

Police officers and nearby citizens jumped to the rescue. Able passengers squirmed away from the wreckage and hurried across the hull. Ships, rowboats, even canoes came chugging and skimming to the rescue. People jumped into the water to be pulled to safety.

Those drowning under the ship were not the only concern. People on the streets rushed the dock to watch in horror. Some fell into the water. Police officers arrived, called for crowd control. The Chicago police officers in their horse-drawn trucks could not drive through, no matter how loud they shouted for space. As the police on dock formed a human chain to shove the crowd back, those who were free dove into the water or leaped to the hull, their boots sliding on the wet, slimy surface. These officers were in danger as well - Officer William Ryan broke his leg as he was helping people scramble off the Eastland.

The screams could be heard for city blocks. At the site of the tragedy the cries drowned out rescue attempts.

A group of welders working on a project nearby came racing over, their equipment clanging and jouncing in tough, work-calloused hands. They immediately set to work cutting holes in the hull. Seconds counted. People were suffocating under the capsized ship.

Then came a cry. "They're ruining my ship! Order them to stop!" Eastland Captain Harry Pederson came shoving through the survivors as they limped and crawled to safety. He commanded the officers to stop the welders. Now forced to scream over the angry shouts from the onlookers: "They're ruining it!" Pederson grabbed at the welders. Officers arrested the enraged Captain. "Take him out of here!" A commanding officer ordered, knowing that if they kept the Captain here, he would indeed be attacked by an angry mob that was already calling for Pederson's blood.

"They're ruining my ship!" Eastland Captain Harry Pederson (holding coat).

"They're ruining my ship!" Eastland Captain Harry Pederson (holding coat).

One of the welders had sweat and tears streaming down his rough, dirty cheeks. His wife and two children were on the passenger list. He and his coworkers assisted choking, limp passengers out of the hull, handing them off to police officers and volunteers. Volunteers carried many. The welder reached for each shaking hand to pull the living up into the air, each time hoping … Later, he would find his family in the morgue.

By 8:00 a.m. on July 25, most living passengers were saved. Police divers went into the murky water. They surfaced holding mostly the bodies of babies and children.

A traffic patrolman, Walter P. Brooks, was just one of the policemen who spent 20 hours in the Chicago River rescuing people and removing the 844 dead passengers: 228 teenagers, 58 infants & toddlers. 70% of the dead were under 25 years old. Twenty-two entire families lost. Many families lost their only breadwinners. The horse-drawn trucks driven by Chicago police officers dutifully carried the dead to makeshift morgues. Bodies laid in rows of 95. Officers remained stalwart, listening to the wails of anguish as the living identified their loved ones.

S.S. Eastland in Cleveland, c. 1911

S.S. Eastland in Cleveland, c. 1911

No one knows how many passengers the rescuers saved. There would be a legal battle much later. The Eastland had a history of stability problems. Documents proved she had changed ownership, dry docked for numerous repairs, and was not deemed safe for July 24, 1915. She was overloaded that day with safety gear all stored on the top deck and too many passengers. But senior management knew dry docking meant a loss in ticket sales, and Eastland had already cost money by being out of commission so often. The famous attorney Clarence Darrow represented the Eastland owners, crew, and engineers in the court case. He won his case, and the Eastland representatives walked away. The company did award the survivors compensation. The Eastland was recovered, repaired, used in the navy, and later scrapped.

A memorial plaque now stands at the corner of Wacker Drive and LaSalle Street in Chicago. The Chicago police officers who risked their lives, worked tirelessly and unselfishly to save people, and assist with the deceased are gone. Like so many officers before them, and still, they masked their feelings to keep the peace and enforce law and order. Some conserved in photographs, the anguish of the day in their eyes.

A Chicago police officer looks on at rescue efforts.

A Chicago police officer looks on at rescue efforts.

Resources

Baillod, Brendon. "Introduction". The Wreck of the Steamer Lady Elgin. Archived from the original on 27 July 2015.

"Eastland (1903)". Builder's Data and History. Maritime Quest. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

"The Eastland - Early Life". Eastland Memorial Society.

Eastland Historical Society http://www.eastlanddisaster.org/history/what-happened

"Eastland Memorial Edition". Western Electric News. August 1915. Archived from the original on 14 September 2011.

Hilton, George W (1995). Eastland: Legacy of the Titanic. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. p. 93.

https://www.chicagocop.com/history/hi...

“The American Tragedy No One Remembers.” (September 26, 2020). Grunge. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Humjr_a8Cps

"The Eastland". Eastland Memorial Society. Archived from the originalon 24 March 2016

Photos

S.S. Eastland in Cleveland, c. 1911 public domain. Detroit Publishing Co. collection at the Library of Congress. According to the library, there are no known copyright restrictions on the use of this work.

View of Eastland from fire tug. By Max Rigot Selling Company, Chicago - Set of 6 Penny postcard supplied by Kathe Kaul Estate Sales of Kansas City, MO, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=24644096

Police officers- no information. From multiple sources.

September 24, 2020

Help solve this 1973 cold case: Earl Tweed & Linda Morris Murders

The murders happened after Earl’s part-time help had departed at 11:30 a.m. Earl, at 75, was not a threat. Linda, four months pregnant, was barely five feet tall and 110 pounds. Angela was a baby. All were easy to overtake. Still, the beatings were vicious, overkill. Later, an officer at the scene would recall, “there was so much blood.” Linda’s husband, Lew Morris, was nearby working at a construction site. He was taken to the hospital where his only child Angela was fighting, in vain, to stay alive. She would succumb to her wounds. His mother, Lettie, was shopping in the area when she learned of the murders. She knew her daughter-in-law was going to Mr. Tweed’s store to inquire about the rental. Officers described Linda to Lettie outside of the store, and Lettie burst into tears. Police cordoned off the scene, but 1973 police training was not as advanced. The crime scene was not as controlled. People were walking in and out of the building: officers, photographers, reporters, first responders. A thin rope of police tape held back the swelling crowd, and they seemed to come from everywhere to gawk at the scene. Dresden Avenue was a busy main thoroughfare, and this was a strange crime for East Liverpool. Right on the main street and “no one saw a thing!” one officer would later comment. A search of the area located Earl’s wallet, empty of cash, on some stone steps leading up to West Ninth Avenue. A claw hammer and a pair of carpet shears covered in blood were located in a nearby trash can. There were also papers from the store strewn about these steps. (Some reports have a man running from the store and witnesses giving a description.) And that’s all police have to go on. Some investigators shared that they knew who killed the four people but could not prove the case. The murders of Linda, her two children, and Earl remained in the “unsolved” files. Despite the advancement of forensics, DNA and other analysis have not helped further the case. The population of East Liverpool has dwindled to less than half of 25,000. The front of National Furniture is boarded closed. Detailed information on at least 40 pieces of evidence, including bloody fingerprints, hundreds of interviews, offers of a reward, and books of reports fill two thick case file binders. Still, the case remains cold. The detectives who worked the case are now deceased. Every rookie East Liverpool officer learns about “the Tweed Case.” Earl’s only daughter recalls her father as a kind man. As a child, she often joined him when he collected rent. She remembers him as giving renters extra days to pay if they did not have full payments. If they had children and were low on funds, Earl would bring them a few groceries. Her daddy Earl always wore a flower in the buttonhole of his suit jacket, she recalls fondly, tearfully. Crime scene photos reveal a tiny flower in his suit jacket’s buttonhole is peeking out between the horrific blood stains on Earl Tweed’s lifeless body.

The murders happened after Earl’s part-time help had departed at 11:30 a.m. Earl, at 75, was not a threat. Linda, four months pregnant, was barely five feet tall and 110 pounds. Angela was a baby. All were easy to overtake. Still, the beatings were vicious, overkill. Later, an officer at the scene would recall, “there was so much blood.” Linda’s husband, Lew Morris, was nearby working at a construction site. He was taken to the hospital where his only child Angela was fighting, in vain, to stay alive. She would succumb to her wounds. His mother, Lettie, was shopping in the area when she learned of the murders. She knew her daughter-in-law was going to Mr. Tweed’s store to inquire about the rental. Officers described Linda to Lettie outside of the store, and Lettie burst into tears. Police cordoned off the scene, but 1973 police training was not as advanced. The crime scene was not as controlled. People were walking in and out of the building: officers, photographers, reporters, first responders. A thin rope of police tape held back the swelling crowd, and they seemed to come from everywhere to gawk at the scene. Dresden Avenue was a busy main thoroughfare, and this was a strange crime for East Liverpool. Right on the main street and “no one saw a thing!” one officer would later comment. A search of the area located Earl’s wallet, empty of cash, on some stone steps leading up to West Ninth Avenue. A claw hammer and a pair of carpet shears covered in blood were located in a nearby trash can. There were also papers from the store strewn about these steps. (Some reports have a man running from the store and witnesses giving a description.) And that’s all police have to go on. Some investigators shared that they knew who killed the four people but could not prove the case. The murders of Linda, her two children, and Earl remained in the “unsolved” files. Despite the advancement of forensics, DNA and other analysis have not helped further the case. The population of East Liverpool has dwindled to less than half of 25,000. The front of National Furniture is boarded closed. Detailed information on at least 40 pieces of evidence, including bloody fingerprints, hundreds of interviews, offers of a reward, and books of reports fill two thick case file binders. Still, the case remains cold. The detectives who worked the case are now deceased. Every rookie East Liverpool officer learns about “the Tweed Case.” Earl’s only daughter recalls her father as a kind man. As a child, she often joined him when he collected rent. She remembers him as giving renters extra days to pay if they did not have full payments. If they had children and were low on funds, Earl would bring them a few groceries. Her daddy Earl always wore a flower in the buttonhole of his suit jacket, she recalls fondly, tearfully. Crime scene photos reveal a tiny flower in his suit jacket’s buttonhole is peeking out between the horrific blood stains on Earl Tweed’s lifeless body. Can you help solve this cold case? Any information can help. Please contact the East Liverpool, Ohio Police Department at (330) 385-1234. Address: 126 W 6th St, East Liverpool, OH 43920. Website: https://eastliverpool.com/departments...

Resources Dunlap, D. (Director). “759 Dresden” (2010). 28th Parallel Productions. Ove, T. (January 3, 2011). Documentary details Ohio cold case from 1973. Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. https://www.post-gazette.com/news/nat... "Sister, aunt of East Liverpool triple homicide victims still hopes for arrest, 46 years later." (October 8, 2019). WKBN First News 27 Website. https://www.wkbn.com/news/cold-case/s... Waight, G. Death on Dresden Avenue. “Murder Will Out!” Unpublished Manuscript. East Liverpool Historical Society. Retrieved September 24, 2020 from http://www.eastliverpoolhistoricalsoc...

September 14, 2020

The 1,036-pound false confession

Doubt cast bigger than Mayra’s shadow: Rosales could not even get out of bed without the help of at least ten strong men, so how did she maneuver to stand, walk, and fall on the baby? She could not even swing her arm with enough force to strike. Eliseo Rosales Jr. was beaten to death. But Mayra was stubbornly refusing to change her story. She tried to pick Eliseo up when he crawled on the floor and fell on him; she told officials. Yes, she was aware of the consequences: this was Texas. The death penalty would be imminent. Death row would accomodate anyone, regardless of physical size. The truth was finally revealed during the preparation for Mayra Rosales’ trial. It was sadder than it was alarming. Before Mayra could go to trial, officials had to find a courtroom that could accommodate her size. Mayra would have to be transported to the courthouse in a moving truck and live in the courtroom on a king-sized mattress. She was already becoming a media sideshow, called a monster. Nancy Grace was disgustingly spitting out the word “fat!” Every chance the crime talk show host got the opportunity when discussing her case. As they worked on her case, ie, studying Eliseo’s injuries, Mayra’s court-appointed lawyers suspected Mayra was covering for someone. A drug cartel was supposed at one time – after all, it was south Texas, and Eliseo, Sr. was speculated of having particular illegal affiliations. Then Mayra’s mental and physical health began to break down. And she started talking. She called her attorney and confessed. The truth was Jamie Lee was an abusive mother, and Eliseo, despite his fragility, was the brunt of strikes, slaps, and neglect. On that March 18, Jamie Lee had become angry that her son was looking at her and cursed him. Then she had kicked him in the chin so that he fell backward, slamming the back of his head on the wall. Next, Jamie grabbed a hairbrush and smacked the baby across the head for not eating. As Eliseo began to gasp for air, the sisters became alarmed and called for the ambulance. While waiting to hear the ambulance’s plaintive wail, Mayra Rosales devised a plan. “I have no reason to live,” she had indicated her great bulk. “So, a death sentence to me means nothing. But you have kids. I’ll say it was me who hurt Eliseo.” Or it might have been Jamie that came up with the plan. According to another account, “When the paramedics came for Eliseo, Jaime begged Mayra to take the blame. ‘I thought I was dying anyway …so I decided to admit that I’d done it to protect my sister because I love her.’” (Zutter). And that was their plan, the story they stuck to until it began to unravel. And it was Jamie who pulled the first loose thread. “I heard she was pregnant,” Mayra explains (“Half Ton Killer?”). As much as she loves her sister, she knew Jamie would never change. This meant Jamie would stay abusive towards her children. So Mayra told the truth.

Doubt cast bigger than Mayra’s shadow: Rosales could not even get out of bed without the help of at least ten strong men, so how did she maneuver to stand, walk, and fall on the baby? She could not even swing her arm with enough force to strike. Eliseo Rosales Jr. was beaten to death. But Mayra was stubbornly refusing to change her story. She tried to pick Eliseo up when he crawled on the floor and fell on him; she told officials. Yes, she was aware of the consequences: this was Texas. The death penalty would be imminent. Death row would accomodate anyone, regardless of physical size. The truth was finally revealed during the preparation for Mayra Rosales’ trial. It was sadder than it was alarming. Before Mayra could go to trial, officials had to find a courtroom that could accommodate her size. Mayra would have to be transported to the courthouse in a moving truck and live in the courtroom on a king-sized mattress. She was already becoming a media sideshow, called a monster. Nancy Grace was disgustingly spitting out the word “fat!” Every chance the crime talk show host got the opportunity when discussing her case. As they worked on her case, ie, studying Eliseo’s injuries, Mayra’s court-appointed lawyers suspected Mayra was covering for someone. A drug cartel was supposed at one time – after all, it was south Texas, and Eliseo, Sr. was speculated of having particular illegal affiliations. Then Mayra’s mental and physical health began to break down. And she started talking. She called her attorney and confessed. The truth was Jamie Lee was an abusive mother, and Eliseo, despite his fragility, was the brunt of strikes, slaps, and neglect. On that March 18, Jamie Lee had become angry that her son was looking at her and cursed him. Then she had kicked him in the chin so that he fell backward, slamming the back of his head on the wall. Next, Jamie grabbed a hairbrush and smacked the baby across the head for not eating. As Eliseo began to gasp for air, the sisters became alarmed and called for the ambulance. While waiting to hear the ambulance’s plaintive wail, Mayra Rosales devised a plan. “I have no reason to live,” she had indicated her great bulk. “So, a death sentence to me means nothing. But you have kids. I’ll say it was me who hurt Eliseo.” Or it might have been Jamie that came up with the plan. According to another account, “When the paramedics came for Eliseo, Jaime begged Mayra to take the blame. ‘I thought I was dying anyway …so I decided to admit that I’d done it to protect my sister because I love her.’” (Zutter). And that was their plan, the story they stuck to until it began to unravel. And it was Jamie who pulled the first loose thread. “I heard she was pregnant,” Mayra explains (“Half Ton Killer?”). As much as she loves her sister, she knew Jamie would never change. This meant Jamie would stay abusive towards her children. So Mayra told the truth.

Charges against Mayra Rosales would eventually be dropped. Jaime Lee and Eliseo Rosales packed their bags and headed for Veracruz, Mexico. She was not about to pay for the crime. Meanwhile, her sister was becoming a media star. A documentary about her life and the case “Half-Ton Killer?” was filmed, and it aired on TLC in 2012. This documentary brought Jamie back to the states, where she was arrested for causing Eliseo’s death. Jamie agreed to a plea bargain and received 15 years in prison for injury to a child; her release date is 2025. The arrest, subsequent indictment, and then her freedom brought Mayra Rosales good fortune. Medical professionals learned of her story and responded. One prominent physician began to assist with full care to help her lose weight and become healthy. By 2013 Mayra Rosales had lost over 800 pounds. She was under the administration of specialists, on special diets, and underwent gastric bypass surgery and surgery to remove excess skin and tumors. She began making national appearances on a variety of news and talk shows to discuss her life. Once again, she was a media darling. Mayra Rosales is credited as the heaviest woman ever to be arrested. At one time, she was the heaviest woman on record. Accusations of murdering a child made her a hot news item. And then her false confession to murdering a child made her a hot news item. In between, 1,036 pounds kept her in the headlines for both. Sources: "7 Facts About Mayra Rosales of TLC Reality special."(January 21, 2013). "800-pound aunt charged with fatally striking toddler." (March 26, 2008). Houston Chronicle. Hearst Newspapers, LLC. Frost, M. & Owens, R. (December 2, 2013). 'Half-Ton Killer' Mayra Rosales Reveals Why She Falsely Confessed to Murder, Dramatic Weight-Loss. ABC News online. https://abcnews.go.com/US/half-ton-ki... “Half Ton Killer?” Documentary. (2012). Keels, J. & Mireles, T. (Directors). Nowzaradan, J. (Executive Producer). Megalomedia. Distributed by The Learning Channel. Mug shot: Hidalgo County Sheriff's Office Photo of Mayra Rosales at home-unknown, not credited.

Charges against Mayra Rosales would eventually be dropped. Jaime Lee and Eliseo Rosales packed their bags and headed for Veracruz, Mexico. She was not about to pay for the crime. Meanwhile, her sister was becoming a media star. A documentary about her life and the case “Half-Ton Killer?” was filmed, and it aired on TLC in 2012. This documentary brought Jamie back to the states, where she was arrested for causing Eliseo’s death. Jamie agreed to a plea bargain and received 15 years in prison for injury to a child; her release date is 2025. The arrest, subsequent indictment, and then her freedom brought Mayra Rosales good fortune. Medical professionals learned of her story and responded. One prominent physician began to assist with full care to help her lose weight and become healthy. By 2013 Mayra Rosales had lost over 800 pounds. She was under the administration of specialists, on special diets, and underwent gastric bypass surgery and surgery to remove excess skin and tumors. She began making national appearances on a variety of news and talk shows to discuss her life. Once again, she was a media darling. Mayra Rosales is credited as the heaviest woman ever to be arrested. At one time, she was the heaviest woman on record. Accusations of murdering a child made her a hot news item. And then her false confession to murdering a child made her a hot news item. In between, 1,036 pounds kept her in the headlines for both. Sources: "7 Facts About Mayra Rosales of TLC Reality special."(January 21, 2013). "800-pound aunt charged with fatally striking toddler." (March 26, 2008). Houston Chronicle. Hearst Newspapers, LLC. Frost, M. & Owens, R. (December 2, 2013). 'Half-Ton Killer' Mayra Rosales Reveals Why She Falsely Confessed to Murder, Dramatic Weight-Loss. ABC News online. https://abcnews.go.com/US/half-ton-ki... “Half Ton Killer?” Documentary. (2012). Keels, J. & Mireles, T. (Directors). Nowzaradan, J. (Executive Producer). Megalomedia. Distributed by The Learning Channel. Mug shot: Hidalgo County Sheriff's Office Photo of Mayra Rosales at home-unknown, not credited.

August 25, 2020

Helena Hill Weed: example of law enforcement treatment du...

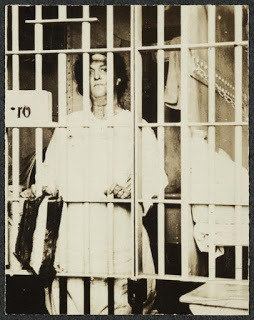

She wasn’t movie-star pretty, and her expression was contemptuous. Most of her keepers probably snarled at her. “Women!” The uniformed officers shook their heads. Even some females looked upon her with disdain. Too many people liked things the way they were, and she was a rabble-rouser. Such was the situation when a photographer snapped the photo of Mrs. Helena Hill Weed behind prison cell bars. She was no stranger to prison. She was no stranger to contempt. But she was not the average inmate.

Born in 1883, Helena Hill was one of three daughters born to a Connecticut member of Congress. She graduated Vassar College and then the Montana School of Mines with a master’s degree in economic geology to become one of America’s first female geologists. Helena later learned she was meant not just to study rocks but to throw them.

Thirsty for knowledge, Helena studied journalism at Columbia. Her education took her to Rome, Paris, and Munich. She would marry Walter H. Weed, who supervised the US Geological Survey.

Lucretia Mott and Elizabeth Cady Stanton had spearheaded the US women’s suffrage movement in the 1840s. Helena joined the suffragists. She learned “Suffs” were not handled delicately by law enforcement. Women who were arrested for speaking out or marching complained of broken fingers, ill-treatment, and poor hygiene in the cells. Marchers were labeled “protesters” and placed in solitary confinement: dark, dank cells with no running water or toilet. Name-calling was the norm, even torture. But creating change wasn’t going to be easy; they told one another. Helena Hill learned quickly.

In 1913, Helena was one of several who testified before the Subcommittee of the Committee on the District of Columbia US Senate regarding police officer conduct during a suffrage parade held March 3, 1913, where thousands attended. It was her first parade. Helena testified how police protected the parade’s marchers until they went through an area where police protection was “very lax,” where some drunks began screaming insults, “it was barnyard language (referring) to roosters and the hens and the cows…” Soon the crowd closed in, with only a line of boy scouts and military men keeping a drunken, disorderly gang of large men from tearing at the marching women. Helena naively asked a policeman, three times, if he could keep the crowd away, and he reportedly told her, “I can do nothing with this crowd, and I ain’t a-gonna try.” Helena explained that the only law enforcement officers who made any attempt to assist were “a young negro officer” and an older “negro officer with a grey mustache.” The drunks grabbed at the “suff’s” banners and even tried to tear at the state flag one woman carried. Other marchers testified the same: crowds pushing in closer, drunks shouting and grabbing, and the lack of police interest in protection. Police Captain Doyle testified there were no problems. He never heard any of the police force ridicule the parade, women’s suffrage, or “the ladies …It never dawned upon (officers) that we would ever have a particle of trouble.” If an officer was not doing his job, it was because he had to stop due to “exhaustion.”

When American suffragists picketed at the White House on July 4, 1917, Helena was there, carrying a banner which read, “Governments derive their just powers from the consent of the governed.” Joined by women of all ages, all socioeconomic backgrounds, who demanded the right to vote. Police officers grabbed her, tossed her sign to the ground, and Helena became one of the first women to be arrested for picketing the White House. She was arrested for the offense of carrying the banner. They locked her up for three days in the Washington, DC jail, hoping she had learned her place. Again, rough treatment, disrespect, and poor jail conditions as expected.

When American suffragists picketed at the White House on July 4, 1917, Helena was there, carrying a banner which read, “Governments derive their just powers from the consent of the governed.” Joined by women of all ages, all socioeconomic backgrounds, who demanded the right to vote. Police officers grabbed her, tossed her sign to the ground, and Helena became one of the first women to be arrested for picketing the White House. She was arrested for the offense of carrying the banner. They locked her up for three days in the Washington, DC jail, hoping she had learned her place. Again, rough treatment, disrespect, and poor jail conditions as expected. The three days in the DC jail had not imprisoned her spirit. In January 1918, officers wrenched her from the gallery, handcuffing her for applauding in court; the judge sentenced her to 24 hours behind bars. That same year in August, Helena Hill’s name was listed as an inmate for 15 days when she was arrested again, this time for participation in a meeting at Lafayette Square, a large park adjacent to the white house. Helena most likely steeled herself for mistreatment. Jail still meant severe punishment for her fellow suffragists. It was a price to pay.

In August 1920, American women were granted full legal voting rights. They paid for it with broken bones, broken hearts, miles of marching, and loss of lives. They sat in jails and prisons where they were tortured, starved, beaten, and harassed. The women experienced police officers, who were sworn to protect and serve, watching them being verbally and physically abused. One of those women was Mrs. Helena Hill Weed.

But she wasn’t just a suffragist. Besides Helena’s involvement in the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage and the National Women’s Party, she held several titles, to include vice-president of the Daughters of the American Revolution, one of the founding members of the Women’s National Press Club, and national secretary of the Haiti-Santo Domingo Independence Society. Helena was a feverish writer for equal rights, to include supporting Haitian independence. In 1927 she ran for Mayor of Norwalk, saying she had kept a household for 30 years and raised a family, giving her enough grit and experience for “municipal housekeeping.” Mrs. Helena Hill Weed died in 1958. She left a legacy, and her children became educated women and advocates for equality.

References

Connecticut State Library. “Finding Aid to the Connecticut Woman Suffrage Association Inventory of Records,” 2016. https://ctstatelibrary.org/RG101.html

Hill Family Papers. Vassar College. 1662-1994, bulk 1835-1970.

Mrs. Helena Hill-Weed. Turning Point: Suffragist Memorial. https://suffragistmemorial.org/mrs-he...

Municipal Housekeeping Job Sought by Mrs. Weed, Opposing Bachelor for Norwalk Mayor. (September 16, 1927). The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Brooklyn, NY.

Nichols, C. (1083). Votes and More for Women: Suffrage and After in Connecticut. New York: Institute for Research in History: Haworth Press.

Stevens, D. (1920) Jailed for Freedom. New York: Boni and Liveright.

Suffrage Parade Hearings (March 6-17). Subcommittee of the Committee on the District of Columbia US Senate regarding police officer conduct. 63 Congress, Special Session of the Senate. S. Res. 499. Part I.

Thorton, S. (February 22, 2019). Women of the Prison Brigade. ConneticutHistory.com. https://connecticuthistory.org/women-...

Women’s Suffrage Timeline. National Women’s History Museum. http://www.crusadeforthevote.org/woma...

Photos

Suffragists' march to the Capitol, Apr. 7, 1913 by Ross, W.R., photographer, 1913. Library of Congress catalog. Marked public domain.

Mrs. Helena Hill Weed in prison, 01/01/1917. Photo source not listed. Library of Congress catalog. Marked public domain.