Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 42

October 14, 2016

The board games you need to know about from Gen Con 2016

I’ve been telling everyone that Gen Con stood for “General Convention,” and that it was shortened for the sake of being unique. But this is not true. It’s actually short for “Geneva Convention”—named for Lake Geneva, where 12 Chicagoan members of the IFW (International Federation of Wargaming) met when they couldn’t make it to their club convention in 1967. The convention has met in California, Florida, and Pennsylvania in years since, but the event’s beating heart has always been in the Midwest. This year saw over 60,000 people in attendance.

The day I arrive in Indianapolis is clear and blue as a robin’s egg. I can still smell mint and corn from driving through the fields down from Chicago. The convention hall is a looming mass of steel and glass and measures almost 1.5 million square feet of space for meetings and exhibitions. I park, check my things, grab my pass, and walk into the exhibition hall. The ceiling stretches far overhead, booths arrayed in carefully organized canyons, staffed by hopeful developers and “industry people.” I greet everything with a mixture of wonder and cynicism.

wade through the tide with me

Experiencing a convention on the scale of Gen Con is like trying to sip water from a fire hose. Every display is part sideshow attraction, part panhandling, part science fair. Each designer is begging to have their game rated, picked apart, played, and hopefully bought and talked about. The sheer volume of games is so much that, in the interest of fairness, I’m trying to list everything I saw with an equal measure of disrespect—boardgames, hairstyles, banter. Grab a coffee and wade through the tide with me:

– For everyone who’s ever wished for a spaghetti-western-flavored card game about dueling wizards set in a post-apocalyptic wasteland, your dream has come true, and its name is Grimslingers (2015).

– Eric Lang, who designed the softly-competitive Bloodborne: The Card Game, has the most magnificent mad scientist hair and diabolical goatee. (2/10 for the Goatee; 3/10 for his Crazy Hair)

– Asmodee’s new game 4 Gods looks like Insane Olympian Carcassonne (2000).

– Despite its family-friendly art style, I’d say there’s nothing family-friendly about Exposed’s public nudity — 5/30 Offensively Naked Suspects

– Vesuvius Media’s Dwar7s Fall looks like Kingdom Rush (2011) in autumn, but the game’s focus is really on exploiting an underpaid and expendable workforce — 4/5 Overworked Dwarves

– Ryan Laukat’s Near and Far should win an award for “Most Earnest Art Style”: it looks like a Hayao Miyazaki-esque take on Journey (2012) — 7/7 Earnest & Inscrutible Characters

– The Betrayal at House on the Hill-inspired Secrets of the Lost Tomb (2015) could win an award for “Most Fonts On Box Art” (four in total). I’m really not kidding. It’s an achievement — 4/1 Fonts

– I blow my whole team’s brains out in a demo of World Championship Russian Roulette, a new bluffing game by the Tuesday Knight Games bros — 5/6 Empty Bullet Casings

– I watch some players test Gil Hova’s The Networks:

“Let me take that Very Serious Dramatic Actor,” says one.

“I need him for the Chainmail Bikini Warrior pilot,” the other says.

A third player sweeps up the Chainmail Bikini Warrior pilot starring That Kid From the Commercial.

Everyone groans.

– The creator of the highly sought-after Potion Explosion (2015), Lorenzo Silva, tells me his game was inspired by Candy Crush (2012). I do have a crush on his game: the rulebook is full of funny asides by a Dumbledore-inspired Potions professor! — 8/9 Pithy Rulebook Quotes

– Isaac Childress’s dark fantasy / legacy / dungeon-crawler game Gloomhaven could be one of the most overpromised games on the floor. It really looks like Childress is trying to make *the* biggest game ever.

– The Spoils (2006) just has too many breasts on its artwork. The CCG is 10 years old this year, and the suspiciously-topped gelatins on its anniversary kit are more than a little tasteless — 7/7 Deadly Sins; ∞ breasts

– If an evening role-playing a bitter technological feud sounds good to you, then Tesla v Edison (2015) is your everything — 2/2 Bitter Inventors

– SeaFall is the perfect seafaring game for anyone who loses their shit over managing cargo holds and naming islands after unseemly body parts. It’s the ultimate boardgamer’s boardgame: cerebral, dry, and mechanically complex, with a set of ever-evolving rules. It’s obviously someone’s [dry] dream, but that someone is definitely not me.

– In Escapehatch Games’ Tell Me A Story, trolling is built into the mechanics of the storytelling gameplay. While Once Upon a Time has been enabling screwy homebrew fairy tales since 1997, Tell Me A Story’s game engine is surprisingly lean and flexible, and isn’t just fairy tales.

– A tabletop adaptation of the 90s game, Centauri Saga, has a Power-Rangers-colored space centipede and guys wearing suits from Halo (2001). It’s a new kind of nostalgia grab — 14/15 Nostalgic Feelings

– So-called “Industry People” seem to have identified there are two diverging interests in tabletop gaming: Players Who Love Miniatures, and Players Who Like Simple Rules. The self-proclaimed “Boutique Nightmare Horror” Kingdom Death: Monster (2015) miniatures game exudes pretension and exclusivity with its soft-lit wooden cases in the far corner of the convention hall — 11/10 Pretension

– LFG’s Orphans and Ashes: Compete with a friend to either burn orphans alive or rescue them! Yep!

– Don Eskridge, who created The Resistance (2009), is shopping around a new game designed to engender deep distrust between friends, and it’s called Abandon Planet.

– I watch two bros misfire as one misreads the orders of the other in Goths Save the Queen. It’s games like this that teach us how truly alone we are — 4/4 Angry Goths (Visigoths—not the kind you probably were thinking)

– Dungeon crawler 100 Swords, like Pokémon, comes in both a red and blue version. Unlike Pokémon, the goal is to kill your particular monster-boss, rather than befriend it.

– Three Wishes plays like a game of Cups (1969), except instead of three cups, there are 14, and you’re trying to make sure none of your three cups has a bomb underneath it — 1/14 Bad Wishes

– Diabolical!’s sentient cell-phone supervillain is trying to take over the world with the help of a grumpy sock puppet and a robber cub. This is exactly what everyone wants — 4/4 Inept Henchmen

– Competitive card game Ashes: Rise of the Phoenixborn (2015) is spinning two new Highlander-esque wizards: a sensual lion tamer and ghostly burlesque duchess — 3/3 Hot Lion Tamers; 4/5 for the Masked Ghosts

– Grizzly Forged claims to have caught and trained wild bears to develop tabletop games. Their demo copy of Sabotile does not look like it was made by wild bears.

– At a buccaneer-themed booth, I demo a prototype of Scurvy Dice and roll all parrots as I build my ship.

“What are the parrots for?” I ask.

“Any dice you want,” the guy says.

I decide the parrots are all cannons.

“You don’t wanna do that,” he says.

Still, I blow him out of the water — 6/6 Parrot Dice

The post The board games you need to know about from Gen Con 2016 appeared first on Kill Screen.

October 13, 2016

Your next mobile game fad is here

Sign up to receive each week’s Playlist e-mail here!

Also check out our full, interactive Playlist section.

Picky Pop (Windows, Mac, iOS)

BY FROACH CLUB

Some videogames are lambasted for their ostensible purposelessness. “Time wasters” is the term usually attributed to them by their critics. Picky Pop would certainly feel feel the insult as one of the most fun, recent time wasters. It is a tile-based puzzle game that tasks you with beating your own high score and little more. Where’s the glory in that? But it’s this type of game that makes the drudgery and duller moments in life bearable. When there is nothing to look forward to or any grand task to keep you occupied, you can pick up Picky Pop and get poppin’. It invites you in, asks you to pluck numbered tiles from its little paws, jig to its playful music, and chase a new high score. It’s a game for all the people stuck in 9 to 5 jobs they’d rather not be doing, or for those in between jobs, or for anyone waiting for a bus. There’s no harm in Picky Pop; it is here to rescue us from the lacunae of modern living.

Perfect for: Loiterers, puzzle addicts, 9-to-5ers

Playtime: Five minutes a pop

Name your price for Picky Pop here.

The post Your next mobile game fad is here appeared first on Kill Screen.

Artist uses videogame to create an “endlessly mutating death labyrinth”

The wonderful opportunity of videogames for an architect is that they allow for the creation of structures impossible to realize in the physical realm. Sure, for many years, pen and paper has offered the same deal, but not quite. Software lends itself to a virtual space that can be freely explored from different angles, and it has systems that allow for easy tweaking of any architectural arrangement—the possibility of stretching a series of buildings into infinity seems that much more plausible in virtuality.

writhing with unstable animation

Peter Burr, a New York-based artist with a keen interest in creating spaces of performance through animation, is very much into the infinite architecture of videogames. This year, that interest led to an installation called “Pattern Language” that was showcased on multiple connected screens across the walls of 3-Legged Dog in New York between September 25th-29th. The name of the exhibition is taken from the term coined by architect Christopher Alexander to describe “the aliveness of certain human ambitions through an index of structural patterns.” The curators of the installation add that the design approach Alexander refers to has been claimed to allow for ordinary people to “successfully solve very large, complex design problems.”

Burr’s installation reflects its titular term through videogame software, creating a world that he describes as “an endlessly mutating death labyrinth” that viewers could peek into. Realized in Burr’s signature black-and-white pixels (as seen in projects like “The Mess”), the criss-crossing pillars and walkways of the city in “Pattern Language” seem alive, writhing with unstable animation. Oddly, the people strolling around inside seem to be less active (or more stable) than the patterns they step across, which constantly fidget with an electronic energy. It’s something that’s perhaps best described as a “video environment,” as 3-Legged Dog called it.

While you have unfortunately missed your chance to see the installation in person, you can stare longingly into the GIFs above and below, which we can all thank Prosthetic Knowledge for providing. But that doesn’t have to be the limit to your interaction with this installation, as 3-Legged Dog mentions that it’s being turned into a videogame with the support of Creative Capital and Sundance. Make sure you keep an eye on that to arrive—we certainly will be.

You can find out more about “Pattern Language” on its webpage. Check out Peter Burr’s website for more of his work.

The post Artist uses videogame to create an “endlessly mutating death labyrinth” appeared first on Kill Screen.

Figment will turn dream spaces into an interactive playground

At last, several months after first revealing concept art and screenshots for its dreampunk game Figment, Danish studio Bedtime Digital has more to show. It comes in the form of a three-minute long video, which features not only the game in action for the first time, but also lead designer Jonas Byrresen talking about where the idea for Figment came from.

As might be expected, Byrresen reveals that Figment was conceived after the studio looked at what people who played their debut game, Back to Bed (2014), had requested. Specifically, it was the chance to walk around and look at more of Back to Bed‘s world, which comprised surrealist, gravity-bending dioramas—the kind of virtual space René Magritte would make. And so it is that Bedtime Digital has leaned into that request when making Figment.

Max Ernst-like fantasy blush

Rather than a puzzle game, as Back to Bed was, Figment is an adventure game that takes place across an interconnected world. All sky islands and bridges, Figment‘s world is actually the manifestation of someone’s subconscious—a psychogeography as suggested by the Max Ernst-like fantasy blush and Alice in Wonderland (1951) color scheme. It’s a place where apples are halved and turned into domestic layouts with tiny windows and doors, and tea pots are similarly given an architectural function, as if the old woman who lived in a shoe (you know, from the nursery rhyme) had inspired a whole generation of architects.

Other than swirling flora and windmills, the most defining aspect of Figment‘s world is the musical instruments you can spot scattered around the place. Byrresen explains that the person whose head you’re inside is deep down a very musical person. But on the outside world this person hasn’t really had the opportunity to show that side of themselves, “to live out their musical dreams,” as Byrresen puts it.

He doesn’t say much more on the subject than that, but the impression Byrresen gives is that you’ll be connecting the various islands in Figment by way of creating music. In the video, you can see the character (what the hell is that anyway?) turning valves to affect where clouds appear, and in the concept art there are signs that trumpets are used to create bridges made of brass. There are also vilains that will try to stop you who, following the example of Inside Out (2015), represent inner emotions like doubt and fear.

“[The villains] are cowards, so they keep running away,” Byrresen said to Polygon earlier this year. “Each world is about finding a way to corner them, and then finally having a chance for defeating them. “You need to face your fears. That’s the way you overcome them.”

Figment is coming to PC, PlayStation 4, and Xbox One in 2017. Find out more on its website.

The post Figment will turn dream spaces into an interactive playground appeared first on Kill Screen.

In praise of Call of Duty: Modern Warfare’s most unusual level

On the Level is a series that closely analyzes individual videogame sections, examining how small moments in games can resonate throughout—and beyond—the games themselves.

///

Call of Duty 4: Modern Warfare‘s (2007) writers understand brevity. Each loading screen provides a satellite image of the upcoming mission, accompanied by a terse overview. “Good news first,” explains SAS operative Gaz, before the opening level. “We’ve got a civil war in Russia … 15,000 nukes at stake.” It’s graceful. Like a soldier, on standby for mission go, while the player waits for action, she sits through an intelligence briefing. It’s economical, too. If you can use them for exposition, why leave your loading screens empty?

Not that the game’s loading screens are always filled with dialogue. On the contrary, Modern Warfare‘s third level, “The Coup,” opens on an eerily quiet God’s-eye view. “Car inbound,” says one anonymous observer, as the camera follows a moving white dot. “Continue tracking,” replies another. Compared to the levels before it, which were explained to the player directly, “The Coup” begins with an ambiguity. Stephen Barton’s foreboding score, the conversation between two analysts, and the satellite image of a Middle-Eastern city are enough to tell us something is going on—but until the camera flickers and blacks out, and then spirals down to ground level, we don’t know precisely what. It’s subtle, but it perfectly sets the level’s tone. This loading screen is not like what has come before. There begins a sense of unease.

Throughout Modern Warfare we change perspectives, playing either as SAS trooper John “Soap” MacTavish, US Marine Paul Jackson or, in a series of flashback missions, Soap’s commanding officer Captain Price. When we are first introduced to each of these characters, the loading screen simply cuts straight to their first-person perspective: straight away, when the action starts, we are inhabiting their bodies and looking through their eyes. However, when “The Coup” finishes loading, we follow—with the camera—down from the satellite view and into a building, staying on the loading screen until it physically enters the head of Yasir Al-Fulani, the deposed president of Modern Warfare‘s nameless, pseudo Middle-Eastern country.

It’s time to pay attention

To be literally steered into his body—for the camera to force its way into his head, rather than simply cut to a first-person perspective—alerts us to the fact that we are about to be shown is noteworthy. This particular first-person perspective is not to be taken for granted: by carrying us from a dispassionate, out-of-context satellite image into the very eyes of Al-Fulani, Modern Warfare impresses that we are being given a privileged view. The eyes are important here. It’s time to pay attention.

We are also made to feel like outsiders. Playing soldier is a typical videogame experience. Being an overthrown, Middle-Eastern president is not. By positioning us as interlopers into Al-Fulani’s perspective and, by extension, the civil war enveloping his country, “The Coup” impresses that our comprehension is limited. Perhaps this particular war, in which we will be once again fighting in as virtual soldier, is not so clear cut. If “Crew Expendable,” the level directly preceding “The Coup”, made us question the probity of our character and his comrades by showing them executing soldiers who were asleep, “The Coup” itself undermines the sense of absolute understanding that we may typically carry into war shooters. Modern Warfare does not deftly place us into Al-Fulani’s shoes. It forces us in—we are invading this body and for once cannot claim to simply have agency, and thus know every answer and be able to control and predict every outcome.

Subsequently, as Al-Fulani, we are dragged through the courtyard of our (now former) presidential house and thrown into the back seat of a car—doubly ominous, since we recognize it as the car that was being tracked during the loading screen. Driven by one of the revolutionaries (Victor Zakhaev, Modern Warfare‘s tertiary antagonist, is introduced here also, as the man in the passenger seat), the car weaves through the war-torn streets of Al-Fulani’s former rule. What happens outside the car is relatively rote videogame spectacle. Jets fly overhead. Tanks roll down the roads. People shoot at each other. More important is how these scenes are viewed and experienced. The only available action is to turn our head to look through either the rear, front or back windows of the car—as Al-Fulani, held at gunpoint, we cannot move.

At the same time, everything is captured inside a natural frame. The outlines of the car’s windows isolate each moment, reminding us they are distant, that, like looking at a picture on a wall, we are viewing them passively. But not thoughtlessly. What could be a gratuitous sequence (look at all the death and explosions!) is saved by Modern Warfare‘s defining us not only as a passive onlooker, but as a helpless one too. As an interloper, resigned to simply moving the camera, we glare at the chaos. But as Al-Fulani, we’re aware these are our people, our country. Protagonists in Call of Duty are usually barely defined—no voice, no face. In “The Coup”, the lack of a fully-formed sense of character allows us to project our emotions out. We do not fear for Al-Fulani, as, aside from a vessel in whom we are traveling, we do not really know who he is. Similarly, Al-Fulani, gazing through the car windows, rather than pleading with his captors, does not fear for himself. Both player and character seem more concerned for the people outside.

There is no opportunity to, or even a suggestion of, escape

At the level’s finale, when Al-Fulani is dragged from the car, the sense of unease that started to build in the loading screen approaches climax. Initially a foreboding, regular beat, the music reaches a crescendo as our perspective—after having been thrown to the floor—tilts up to reveal a stake, already covered in blood, in the center of an auditorium filled with chanting rebel soldiers. The player and Al-Fulani both have the same realization, but still there is no opportunity to, or even a suggestion of, escape. Later, when the player, as US Marine Sergeant Jackson, crawls out of a wrecked helicopter after being caught in a nuclear explosion, there is a sense of struggle. Though Jackson eventually succumbs to his wounds and the screen fades to white (thus signaling the Call of Duty trend of killing at least one playable soldier per game), he makes a noble effort to live. Modern Warfare is a game filled with action and movement—even as our character lays dying, we can still move him around. And so the ability to only move Al-Fulani’s head, even when faced with certain death, lends to “The Coup” a sense of resignation and melancholy. Al-Fulani and his regime, patently, are both finished.

And why not? While Al-Fulani remains a mute, passive and observing character, rebel leader Al-Asad gives a spirited and rousing speech to his troops. The specifics of this revolution are never revealed (despite implying Al-Fulani’s dismay for his people, Modern Warfare never confirms he was a good leader) but certainly, in “The Coup”’s closing sequence, you understand why the rebels have won. Dressed in red, marching around the execution floor and yelling into a TV camera, Al-Asad is a dynamic presence. Al-Fulani, especially considering how little the player can move him, is comparatively flaccid—one gets the sense his government has been in power far too long. There is, however, a small twist in this sequence. As well as Al-Asad, the execution floor is occupied by the hitherto unidentified Imran Zakhaev. A tall, bearded man in a long coat, when Zakhaev stares directly into Al-Fulani’s eyes, you get the sense he is the one really in charge. The way he hands the gun to Al-Asad confirms it.

Rather than give it to him grip first, Zakhaev points the gun straight at Al-Asad’s chest. It’s the smallest of animations, but the rebel leader, for a split second, stops dead in his tracks, obviously intimidated. Again, we see how economically Modern Warfare is written. Rather than explaining that Al-Asad is being manipulated, the writers, in the briefest and most naturalistic of instances, show it. Later, when it’s revealed Al-Asad was merely an underling and the true antagonist is Zakhaev, it’s still an unexpected turn in the plot but not arbitrary. “The Coup”, in its final moments—even before Al-Asad puts the gun between Al-Fulani’s eyes and, with a bang, the screen cuts to black—sets up Modern Warfare‘s villains.

Almost reluctantly, “The Coup” pulls us into the head of Al-Fulani. The spiraling camera pan in the loading screen, compared to the flash cuts at the start of the rest of Modern Warfare‘s levels, represents labored movement, as if we are being dragged into somewhere. With the precedent set—you are an invader, looking outward—“The Coup” directs our attention to the chaos around us, using in-world frames and limited interactivity to tell us that we can only look, not touch. With Al-Fulani’s unresisting death, the level ends on an appropriately pensive note. At the same time, the implied back and forth between Zakhaev and Al-Asad hints at the intrigue, drama, and excitement to come. It’s the set up for a game which, more than its predecessors, values both great, action spectacle and small moments of player and character introspection. There will be times, later on in Modern Warfare, where characters do shocking things. “The Coup”, by forcing us into a position where we are trying to comprehend violent and alien circumstances, opens our minds to those subsequent events.

The post In praise of Call of Duty: Modern Warfare’s most unusual level appeared first on Kill Screen.

Duke Nukem 3D is back (again) like an old uncle telling 20-year-old jokes

Like uncovering a spiral-bound notebook full of junior high poetry, Duke Nukem 3D (1996) is back once again to remind you of what passed for “edgy” in the late 90s. After a half-dozen repackaged versions over the past few years, a sizable anniversary is enough for Gearbox Software, the current stewards of 3D Realm’s 1996 FPS “classic,” to give everyone another chance to re-purchase it.

Including a brand-spanking new lighting system and a fifth episode created by the game’s original level designers, Duke Nukem 3D: 20th Anniversary World Tour manages to play the way you remember the game and thankfully not how it actually was. Nostalgia has a way of scrubbing the rough edges off, and a press of a button shifts the view from the updated lighting to the original’s simplified look to show just how poorly the original’s technology has aged. Removing the technical limitations of the time while retaining the art, geometry, and pixel-work, the full 3D rendering makes this one of the best presentations the title’s ever had, and re-recorded voicework means that John St. John’s vocals for Duke have never sounded gravellier, for better or worse.

an extended weed joke through Amsterdam

Essentially, this is the best version yet of an exceedingly dumb game, like a remastered Blu-Ray edition of a Mystery Science Theater 3000 film. The full 3D rendering of the levels—ironically, for a game with 3D in the title, 3D Realms used something of a “2.5D” system to account for vertical movement—allows you to enjoy the spectacle in all angles, rather than feel hampered by distracting visual artifacts. (To get a sense of what I’m talking about, turn off the updated visuals and look up and down.)

In case you were on the edge of your seat about the fifth episode’s plot implications to Duke Nukem 3D’s Los Angeles-centric storyline: unfortunately, the rest of the world has fallen to the same alien invasion that wracked California during the original campaign. Hopscotching around major world cities, Duke kicks ass, chews bubblegum, and generally destroys anything in his path in London, Moscow, and more. Naturally, the first level of the new episode is an extended weed joke through Amsterdam.

Blasting through each city brings to mind why Duke Nukem 3D felt so notable back in its time—rather than Doom’s (1993) exciting yet abstract level designs, Duke gets to mow down aliens in football stadiums, high-rise apartments, and trashy theaters. You’re able to get a sense of where they are in space, making the levels themselves just as memorable as Duke’s one-liners. Designer Richard “Levelord®” Gray (yes, there is a ® in his nickname) even made a point to include his Moscow apartment in the new level through Russia.

maybe this release should serve as both a victory lap and tombstone

It wouldn’t be a Duke Nukem release without some form of controversy, though World Tour’s particularly tame scandal shows Duke might be mellowing a bit in his old age. Rather than reigniting some brand of moral panic, Gearbox has riled the fanbase by being too conservative with World Tour. As with nearly any popular PC game of the era, there was a flood of bargain-bin add-ons, mods, and additional bits of Nukem-flavored flotsam and jetsam that were available to bolt onto the original game. While most of the semi-official content was collected in previous releases of the game (which have since been pulled from digital marketplaces), nearly all of it has been excised for World Tour’s more streamlined, straightforward package. What we’re left with is a polished rehash that should stand as a suitable release of a notorious FPS for at least another decade—until the next re-release, that is.

Considering that Duke’s original sidescrolling DOS adventures have been all but forgotten, and Duke Nukem Forever’s harrowing 15-year-long development cycle resulted in possibly the nadir of the medium as a whole, maybe this release should serve as both a victory lap and tombstone for ole Duke. We don’t need more from him, and while there’s still some tawdry amusement to be had in those classless one-liners, he is best left to the pile of childhood obsessions. There’s a reason I stopped writing poetry after junior high, and I’m certainly in no hurry to read any of it aloud.

Duke Nukem 3D: 20th Anniversary World Tour is available on Xbox One, PlayStation 4, and Windows.

The post Duke Nukem 3D is back (again) like an old uncle telling 20-year-old jokes appeared first on Kill Screen.

1930s-style animation game Cuphead won’t arrive until 2017 now

Cuphead creator Studio MDHR was trying to get its game out exactly 80 years from 1936—the year when a Japanese cup-headed character in a short propaganda film turned into a tank to defeat a bunch of evil Mickeys. Now, however, Cuphead will be released 81 years after Cuphead’s grandpa was introduced to the world.

Studio MDHR announced this week that Cuphead will be released for Xbox One, Windows 10, and Steam in mid-2017 now. And this isn’t bad news; it means Studio MDHR won’t have to cut content from the game to make a tight deadline. “It would have meant releasing with fewer bosses, less platforming levels, as well as some stuff we haven’t even made public yet,” Studio MDHR’s Ryan Moldenhauer told me. “We had also always wanted to do a full third-round of polish across the entire game.”

“It would have meant releasing with fewer bosses [and] less platforming levels”

Moldenhauer added that the studio as a whole is confident it’s made the right decision of not sacrificing quality for an earlier release date. “Because Cuphead is our first title, we want to make sure we release the game as we’ve always imagined it,” he added. “We consider ourselves extremely lucky—we have the resources to allow our team to keep working into 2017. We know this is not an option for many developers.”

So, try not to be too sad. When Cuphead is released in 2017, we’ll be getting a bigger and better game than if it were released this year. After all, those hand-drawn and hand-inked visuals can’t be a quick process to perfect; the extra time will give Studio MDHR a little extra time to “deliver the game [it’s] always wanted to make,” Moldenhauer said.

Cuphead is a classic run-and-gun action game with platforming elements. Keep up with development by following Studio MDHR on Twitter.

The post 1930s-style animation game Cuphead won’t arrive until 2017 now appeared first on Kill Screen.

Thumper is here for a beatdown

I’ve only been to one Lightning Bolt concert in my life, but it left a serious impression on me. The band—comprised of duo Brian Gibson on bass and Brian Chippendale on drums and vocals—set up their gear on the floor in front of the stage with a stacked wall of amps behind them. The music is loud and fast, a flurry of noise-metal bass churn, blistering drum rhythms, and distorted, indecipherable shouts. The crowd was a compact mass of bodies, not so much a mosh pit as a sweaty blob fighting against the shape of its container. There was no concrete line separating audience from performer; the band in perpetual risk of being swallowed whole by the undulating pool of fans. The spot right in front of the drum kit is the most intense—whoever is there has arguably the best view of the show in the venue, but they’re also the most at risk of getting shoved into a swirling drumstick.

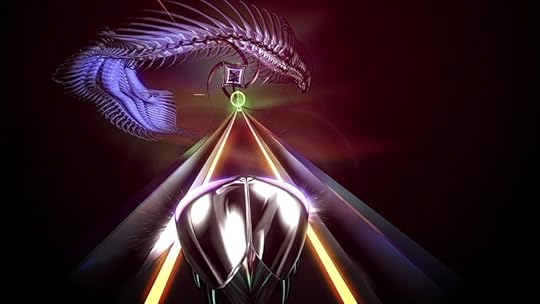

In addition to playing bass in Lightning Bolt, Brian Gibson has also worked as an artist on several tentpole music games over the years, including Guitar Hero (2005) and Rock Band (2007). Since then, he’s formed his own studio, Drool, with ex-Harmonix programmer and designer Marc Flury. It’s fitting, then, that for a good chunk of Drool’s debut game, Thumper, I felt like I was the one teetering over that Lightning Bolt drum set, barely retaining composure against a relentlessly applied pressure. In Thumper, you control a chrome scarab careening down an endless twisting highway (basically the album cover of Journey’s Escape as a videogame). Like many rhythm games, Thumper asks players to tap a button in time with onscreen cues, limiting the complexity of possible maneuvers to one button, plus one of four cardinal directions on the thumbstick. But don’t let the simplicity fool you. Thumper makes up the difference with menacing timing, an intolerance for failure, and a degree of graphical distraction that will obliterate most players on their first time through.

spartan cascades of power kit drum beats

In playing Thumper, you’re ostensibly flying through 2001: A Space Odyssey’s (1968) Star Gate scene, though if that’s the case then it seems to have been distorted by DOOM’s hellworld. The landscape is a red void, inhabited by the floating skull demon that concludes each level, and a host of starfish fractals that erect obstacles along the way. There’s a cold distance to the game’s overall aesthetic, which makes it all the more arresting when so much of it is right in your face. You’re able to execute “Perfect Turns” by flicking the thumbstick in the direction of the outgoing path just before slamming your body against the wall. There are moments when you’ll see a turn pop up on the spindly path ahead, seeming to offer plenty of space to ready your timing and execute a maneuver. Just as often though, the distance induces anxiety as you struggle to find the correct rhythm in the lead up. For all the reflective surfaces, hollow tubes, and endless expanses, the feeling of playing Thumper can be quite imposing and claustrophobic.

Thumper is a trial by fire, or explosive chrome, as it were—there is no “Easy” mode or free-run practice area. This extends to the music of Thumper, which eschews four-on-the-floor bangers and even the frenetic-yet-metered patterns of jungle or drum and bass you’re likely to find in many rhythm games. Instead, the soundtrack is spartan cascades of power kit drum beats, as if you ripped the rhythm track out of an action movie trailer and set it to loop. There are patterns, but in many cases they aren’t apparent unless you hit all of your marks. This means you can’t feel your way through stages by matching the beat; you have to create an additional drum fill that compliments the backing track. This was one of the trickier aspects of Thumper to wrap my head around, as it’s such a divergence from the way most rhythm games function.

As such, I struggled with the middle half of the game (there are nine levels total). The difficulty spikes early on and my scores quickly dove from alternating As and Bs to consistent Cs. The tracks become unpredictable and near impossible to execute without taking hits and dying in an effort to learn the patterns of turns and thumps necessary to clear a stage. Quick turns in tunnels seem downright unfair for those looking to sail through levels on their first attempt. There might not be a Sword of Damocles looming overhead in Thumper, but there are hundreds of tiny guillotines lying in wait to decapitate you at a moment’s notice. There are times where the game is on the verge of becoming a slog.

I just had to learn how to listen to it

However, upon reaching level six, I started to better recognize the game’s patterns and curveballs, even clearing a few stages on my first try. All of a sudden, deaths seemed less the game’s fault than my own. I went back and played levels I struggled with before and breezed through them with only a handful of fatal errors. It’s not a rare thing to get better at a game with more practice, but it’s worth noting in regards to Thumper for fear that the intense difficulty might be taken as bad design. The truth is the contrary. Thumper is less unfair than it is uncompromising, and feels right in line with the recent crop of run-based, arcade-style games (e.g. Spelunky and Furi) where the progress is incremental and the deaths are many. The struggle not only makes the payoff of slick execution in Thumper quite satisfying, but it’s also revelatory. It turns out the game was telling me everything I needed to know, I just had to learn how to listen to it.

Thumper is a remarkably physical experience despite the fact that you control it with such modest thumb gestures. Other music games have supported the more complex movements of full-body dancing and complete band simulations via plastic instruments. So, at first glance, Thumper appears to be a return to the simpler days of Amplitude (2003) and Frequency (2001). However, unlike those games, which felt like they were better suited to being played with an MPC than a gamepad, Thumper’s controls feel uncompromisingly situational. There is no scale recognition, only movement prompts, and the basic controls reinforce this. Notes have been replaced with actions: thump, slam, grind, launch, etc. And each of those actions comes with an onomatopoeia-ready sound effect that illustrates them in a pronounced fashion. The reverberating “BOOooOOoom” of bass rumbling after landing a stomp at the end of a jump is particularly satisfying, but my favorite is the knife sharpening “SHHHHHHINK” when you simply hold “Up” on the thumbstick to open the beetle’s wings at the correct time. It makes me want to go listen to Photek.

I might have started off playing Thumper bracing myself from falling on Lightning Bolt’s cymbals and toms, but by the end I felt like the one holding the drumsticks. There’s something to be said for the sensation of Thumper’s mid-game, where survival is the goal, ignorant of whatever score comes along with it. You’re the audience member just holding it together long enough to see the show. But to truly feel in control of Thumper is to feed off of a kind of daredevil bliss. When you can see through the frenzy and begin playing with restraint, you might not feel like a musician, but you do feel like a performer worthy of an audience. Thumper doesn’t come with a wall of amps and heaving waves of bodies crashing all around you, but it does successfully channel that sensation all the same.

For more about Kill Screen’s ratings system and review policy, click here.

The post Thumper is here for a beatdown appeared first on Kill Screen.

The overclocking community gets nostalgic

This article is part of a collaboration with iQ by Intel .

Like car fanatics who modify new or classic models to make them look and perform better, a growing overclocking community of passionate PC modders is pushing the limits of old and new computer technologies.

In the world of computer modding, overclocking is the dark art of custom tuning computer parts to achieve a performance boost. The unbridled passion for tinkering with chips and specs is spreading across generations, pulling this dark art out of the shadows. “Overclocking has evolved into a sport,” said Dan Ragland, an engineer at Intel. “It has really taken off in the last 5 years.”

Nerdy Ninjas Render Rig, by Travis Janks

Nerdy Ninjas Render Rig, by Travis JanksOverclocking has become a phenomenon as more people custom-tune the stock performance of their computer hardware. Traditionally this has been done by entering the computer’s basic input/output system (BIOS) to adjust the stock clock speeds as well as the voltage going to the components. A number of settings can be tweaked, including the speed of the processor, graphics card and memory. An overclocked computer can lead to better gaming performance or bragging rights for breaking benchmark records.

In recent years, new tools like the Intel Extreme Tuning Utility, make overclocking quick and easy. There’s no shortage of forums, Facebook pages, modding competitions and video series like the recent Expert Mode: Rig Wars series.

overclocking is a dark art

While many are poised to break speed records tweaking the first line of 10-core Intel Extreme Edition processors, overclockers on the other side of the spectrum focus on tweaking older, more archaic tech. There’s even a monthly contests known as the Old School is Best School challenge, where modders show off their hardware skills with a nostalgic twist.

At overclocking competitions, the team who brings its various computer components to the fastest speed without frying the motherboard wins, but when the overclocker uses retro equipment, including outdated processors and obsolete graphic cards, it can change the game.

“There is a lot of nostalgia in this for me,” said Pontus Arvidsson, a 27 year-old overclocker on the team TechSweden. “I was quite young then and couldn’t afford to buy everything I wanted. [The appeal] is based on what I dreamt about getting my hands on.”

Work and photo by modder Max1024 from Belarus

In the second round of the contest, for instance, teams were limited to the first generation of Pentium 4 processors, which came out 16 years ago. To everyone’s amazement, Stelaras, an overclocker from Greece, won the round by pushing a 1.5GHz processor to the speed of 2,220MHz, 48 percent faster than it was intended to go.

the thrill comes from doing something that seems impossible

In Old School events, the thrill comes from doing something that seems impossible. Of course, all the fascination with out-of-date tech comes at a price. Even when ridiculously overclocked, old components could never dream of matching the capabilities of today’s stock chips. New processors need to be powerful enough for live-streaming and playing games with beautiful graphics at the same time, according to Intel’s Mark Chang. “Current generation CPUs already come with so much power and performance that most people don’t find it necessary to overclock their CPUs,” said Chang. “However, the ability to customize the system to get exactly the performance you want is one of the coolest, most unique aspects of the PC.” A decade ago almost all processors were overclockable, but now only specific performance processors come “unlocked” and ready for overclocking.

Work and photo by Macsbeach98

One of the big shifts since manufactures began selling processors unlocked is the rise of products built from the ground up for overclockers, said Travis Jank, owner of NexGen Computing and modder who competed in “Expert Mode.” Jank has a library of every processor since 2002, before the release of software-assisted overclocking existed. “With new technologies, you can push performance 200 to 300 percent right out of the box. Tell me another product that can do that!”

new hardware is almost becoming too good for overclocking

For members of the Old School community, overclocking retro hardware may be tedious but it’s way more fun than tweaking new tech. The art can be fascinating as a way to test a competitor’s mettle, and in the community’s eyes, old chips actually lead to a higher level of competition. Old Schoolers prefer old tech to new because it’s relatively easy to destroy a chip while overclocking it, and zapping a $300 piece of equipment in the heat of a competition hurts. “The competitions are quite popular because they are cheap to enter,” said Pieter-Jan Plaisier, director of the HWBOT overclocking community. “Even if you break the hardware, replacing it isn’t a big problem.” In addition to keeping the costs down, Plaisier said that old hardware is rife with technical and electrical challenges that competitors need to overcome.“Overclocking the old components requires a lot of research,” he said.

Work and photo by Max1024

Many overclockers view the unfriendly qualities of old technology as a good thing when it comes to battles for supremacy. “With old tech, you need to be able to handle a soldering iron — that was a must to be a good overclocker just five years ago,” said Arvidsson, referring to how overclockers need a hand tool that melts pieces of metal onto the circuitry. “Nowadays, you don’t even need to think about soldering on modern chips.” In his view, new hardware is almost becoming too good for overclocking competitions. “Because the motherboards nowadays are really advanced, most of the things just work, but on those old ones you really need to modify them to get the most out of your hardware.”

Just like the most extreme overclockers — those who do things like cool their CPUs down to sub-100 degree temperatures with liquid nitrogen — old school tech modders love perfecting the imperfect. “Even if you buy the best motherboard, you know that it is far from perfect,” he said. “You know that there are a lot of modifications that you need to do to get the full potential out of it.” Ultimately, it’s precisely that untapped potential that keeps innovative overclockers — of old and new technology — coming back for more.

Ken Kaplan contributed to this story.

Check out these links to learn more about gaming tech such as the Intel Core i7 Extreme Edition processor, Turbo Boost Max technology 3.0 and overclocking.

The post The overclocking community gets nostalgic appeared first on Kill Screen.

October 12, 2016

Pavilion and the maze as metaphor

When I was younger, I got lost in the works of Jorge Luis Borges. In my hubris, I assumed I “got” him in a way that would let me use the tools of literary study to recognize patterns, symbols, and themes. His hermetic prose held secrets that I thought I had unlocked in my sophomoric self-satisfaction. I assured myself that knowing Borges’ favorite subjects, like mazes and infinite libraries, are actually metaphors for the text itself was a revelation that only I and a few select others could hold dear.

I was wrong, of course. Not about the obvious readings, but about the uniqueness of my perspective—people have been reading and puzzling Borges’ work for far longer than I’ve been alive, each insight more clever than any I could’ve conceivably offered. But I didn’t know that at the time, not from the safety of my dorm room in Jackson, Mississippi. Instead, I obsessively stumbled toward some kernel of knowledge sealed away in the alleys of the text, certain that I had unearthed something new.

toying with the pieces of the game like a writer constructing a sentence

Until I began playing Chapter 1 of Visiontrick Media’s Pavilion, I hadn’t thought about my early readings of Borges for a long time—almost long enough to seal them away in that vault we all have for storing embarrassing moments. Having played several puzzle games in which I help some unnamed protagonist perform a series of tasks to chase some ambiguous goal, I wondered immediately what this game could show me that I hadn’t seen elsewhere. Even its set-up—a man in a suit, an enigmatic woman, and a melancholic fantasy world entwined with a modern domestic space—is reminiscent of Jonathan Blow’s Braid (2008), a game that since its release has become a staple in discussions about how games and literature intersect.

My initial skepticism about the game faded as I spent more time with it and considered more closely its use of player perspective. Pavilion’s creators have called the game “a fourth-person adventure.” Instead of controlling the game’s protagonist directly, the player manipulates objects in the environment—sliding platforms, ringing bells, turning lights on and off—to spur the protagonist on his way. This perspective keeps the player at a distance, essentially turning her into a textual arranger, toying with the pieces of the game like a writer constructing a sentence.

That’s why I thought of Borges and my first experiences with his prose. As I played Pavilion, building and discovering sentences through the ornate pathways of the game, I started to see parallels. The protagonist’s fixation on the furtive woman always out of reach recalled the obsession-inspiring titular object of Borges’s The Zahir (1949). I thought of Ts’ui Pên’s labyrinthine novel in The Garden of Forking Paths (1948) as I moved Pavilion’s main character from point to point, crashing against dead ends in wooden halls and forests of stone pillars. Each stage and series of puzzles reminded me of the infinite hexagonal rooms of The Library of Babel (1941). Pavilion even alludes to games like Braid, in a similar fashion to how Borges recycles the works of Cervantes, Shakespeare, and classical and biblical literature. Somewhere amid the curious puzzles and the dreamlike neoclassical ruins painted with an art nouveau pallette, Pavilion became about the language of play.

Pavilion is a series of puzzles that become sentences

For this reason, I find game’s creators use of the phrase “fourth person” a clever one, especially when considered grammatically. The English language has no account for what the “fourth-person” would be, the closest being using the word “one” to mean a general or hypothetical perspective (e.g. “One would think that article is bordering on tedious”). The player’s perspective in Pavilion operates with similar obviative omniscience. In Pavilion, more than any other game I’ve played recently, I understood my place in relation to the text, not as player but as a writer. Pavilion is a series of puzzles that become sentences. The painted visuals and Tony Gerber’s haunting soundscape establish mood for the actors in the narrative: protagonist as subject, his actions as verb, the ambiguous goal as object. I was simply there to put it in order or to play with its syntax.

Consequently, Pavilion strikes me as a particularly Borgesian game, especially given that games seemed to be what Borges wrote. The ways in which his stories fold into one another, sentences linking back to other sentences, turn them into hypertexts legible without computers. His fictions seem like antecedents to what Pavilion hopes to accomplish through its fourth-person perspective. The attentive player, like Borges’s attentive reader, uses the power afforded from a removed perspective to engage in the processes of artistic creation by showing us that each frame, each sentence is built through a number of parts to be arranged rather than a puzzle to be solved.

To that end, Pavilion’s classification as a puzzle game in the traditional sense is suspect, if not outright boring. I would hesitate to play Pavilion for its puzzles, which are not that complex, the same way I would not read Borges’ works for their plot or characters. Instead, I will likely return to Pavilion to get lost in its digital labyrinths, to discover how objects can be rearranged to play with the narrative of a faceless man in a suit. When I return to Pavilion’s twisty little passages in Chapter 2 next year, I hope recall that feeling of blissful disorientation I felt in the dizzying corridors of Borges’ prose.

For more about Kill Screen’s ratings system and review policy, click here.

The post Pavilion and the maze as metaphor appeared first on Kill Screen.

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers