Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 278

March 26, 2015

The videogame trying to change how we treat the homeless

See through their eyes. Feel the dejection.

March 24, 2015

Hotline Miami 2 force-feeds you sleaze

The one that goes all the way.

A quick primer on 3D sound, or how to create convincing worlds in virtual reality

Finally, audio that appreciates for your innate denseness.

Some madcap designer made a roguelike that's controlled by a synthesizer

The novelty of Crypt of the NecroDancer is that it spins the cruelty of the roguelike into a beat-matching formula. You have to hop across the grid-based dungeons and attack the beasts that get in your way to a rhythm. Looking at it now, Crypt of the NecroDancer is probably the friendliest way to introduce a musical foundation to the roguelike—it's more action-oriented, less drawn out tactical decision-making. The Broom Institute's Synthesizer, on the other hand, is an example of how you might make a systemically dense sub-genre (the roguelike) even more complicated with the addition of a music-based theme.

the "master volume" represents your health points

Simply put, Synthesizer is a roguelike that is dictated by the changing values of the titular electronic instrument. To convey all the relevant information of a game controlled by a synth, the interface has been made to match that of a VST (Virtual Studio Technology)—the analog music studio made digital. There are pointy knobs that twist between states and multiple LCD displays to observe between each move you make.

If you look at a screenshot of Synthesizer, then the 8x8 grid containing a visual representation of the game world in the bottom left, and the battle log on the bottom right, is what most roguelikes will display. Everything else is done in the background. Whereas Synthesizer pads out the rest of its screen with tools used to tweak and analyze electronic music, and that you are required pay attention to in order to survive its dungeon crawl.

If you're not familiar with VSTs at all then attempting to play Synthesizer is an overwhelmingly daunting task. Even if you do know your way around a VST, it's going to take a while to marry its terminology to that of the roguelike. In the game's highly necessary instructional video (above), Synthesizer's creator explains that a "beat" is a "micro-turn," while the "pattern" can be understood as a "level," and the "master volume" represents your health points. For the most part it all translates with ease.

your tactical decisions mimic the process of composing a song

But this isn't merely a cultural exchange program for nouns. The top half of Synthesizer's screen is where matters become more complex. You can see two Oscillators: one determines whether your attacks will hurt your enemies or cause self-harm, the second one does the same but for your enemies. It's the sound waves in these Oscillators that you need to pay attention to. If they fall into the negative values then you'll hurt yourself, so you want to only attack when the waves are in the positive values.

Below the Oscillators are Filters. These are affected by items that you pick up which, ultimately, change the sound waves in the Oscillators. An amplifier, for example, increases the height of the wave and therefore the attack damage. Whereas a low-filter pass will cut out all positive values meaning that you can only self-harm. There are also ways to change the shape and width of the waves.

Lastly is the step sequencer. Located bottom-middle, this displays when you (represented by the @ symbol), enemies, and the effects will move. Each square across the sequencer's grid is a beat, and each one that is filled in black shows you when the unit it refers to will move. You, the player (represented by the top row), can only move every four beats, but some enemies can move every two beats, meaning that they appear to take big leaps across the game world as you move.

That's more or less the basics of Synthesizer. And if the video above isn't cutting it for you then there's also a written version of the instructions that you can read through to make sense of it all. Hopefully, I've been able to get the idea of how its various components interact with each other, as the beauty in the design of a game such as this cannot be seen or shown, it has to be understood, preferably by trying it out yourself. Sure, it's complex as hell, but once everything in Synthesizer slides together and you're able to determine when to take a turn or skip a beat, you find that your tactical decisions mimic the meticulous process of composing an electronic song.

You can play Synthesizer for free in your browser over on itch.io.

March 23, 2015

The latest, swankiest flashlight design is inspired by a royal scepter

Brendan Keim was walking through the National Portrait Gallery in London last September when he stumbled upon a painting of a man with a long thin scepter. Intrigued, he snapped a photo and quickly sketched the object in his sketchbook, along with a note that it could make a pretty interesting light. “I didn’t think about it for a long time afterward, because I wasn’t sure how it would all work,” Keim says. It wasn’t until the New York–based designer revisited his sketchbook in January that he thought of a way to actually build the device. “I was like, ‘Oh—I can make this. I know how to make this.’”

The eventual result of that expedition and sketchbook documentation is the Volta Torch, named after Alessandro Volta, an Italian physicist and the inventor of the battery. The long, slender brass flashlight is an exercise in aesthetics and function—as well as a challenge in feasibility, with its impossibly thin casing, curiously powered by eight 1.5-volt hearing-aid batteries wired in series. “For me, it was really just an experiment in, ‘Can this physically work? Can I make a flashlight?’” Keim says. “And, ??How simple can I do it?’”

Keim sees it as the world’s swankiest flashlight

Keim is a lighting designer by trade, working for Lindsey Adelman by day. In his own time, he experiments with a range of personal work that focuses on interactive experiences, often involving some element of programming or code. “I really enjoy tactile, analog inputs and I think a lot of my work has to do with controlling a digital world through those analog inputs,” he says. “For me, I see it as the era in which I grew up. I’m a child of the eighties, this crossover period in between analog toys and digital toys.” Looking around Keim’s home studio, his love of that era is evident, seen in large stereo knobs and boxes of every type of LEGO imaginable. His approach to the Volta Torch is no different.

The "elevated flashlight" switches on with a subtle twist of the head, which closes the threaded piece, completing the circuit and illuminating the LED bulb at its tip. Keim sees it as the world’s swankiest flashlight. “Not high-end from a technical point of view, but from an aesthetic point of view,” he explains. “Something that isn’t meant to go in your junk drawer or your utility closet. This is what you bring with you in the middle of the night to go use the bathroom.”

To begin the project, Keim started by creating parts in SolidWorks, loosely constructing possible ways the object could go together. He worked between SolidWorks and a few rough initial prototypes, revising his drawings each time to reduce the number of parts. The biggest challenge, however, was figuring out how an object with such a small diameter could be powered. It wasn’t until the designer was standing in the aisle of Rite Aid that he had his eureka moment.

“Originally, I was trying to figure out how to use AA or AAA batteries—trying to decide what size tube I could purchase to fit that,” Keim says. “But then you have to take a step back and think, ‘Am I limited to just AA and AAA? What standards are out there?’” Standing in line, Keim spotted hearing-aid batteries, alluring for their small diameter and substantial power. “I was like, ‘Whoa. Those power some pretty sophisticated technologies. How could I stack these up?’”

With 1.5 volts per battery, Keim was able to stack 8 together to create 12 volts, enough to power his replaceable LED bulb. After stacking the batteries, he shrink-wrapped them inside a tiny tube of plastic for easy placement. The battery stack sits between a long threaded piece of brass rod and the head of the device, a section of which consists of an LED, a socket, a pre-fabricated nylon connector and a small screw that holds those pieces together.

a project never has to be finished

For Keim, making the Volta Torch has been a process of reduction, trying to use the least number of parts possible. And for his next iteration, the designer plans to reduce things further by machining the head from one piece of solid stock, rather than hacking existing lamp hardware (the nylon piece). That change will make manufacturing easier for the designer, as well as improve the overall aesthetic of the object, which shows slight variations in the gradation of the brass as it transitions from piece to piece. “When you’re dealing with different pieces of brass from different manufacturers, the quality is different as well,” Keim says. “It makes it look like a cigarette or a magic wand, which I don’t particularly care for. To me, this is a fairly refined but still very rough prototype.”

Although Keim did his undergraduate degree in industrial design at Pratt, and a graduate degree in furniture design at RISD, he has also managed to amass a vast amount of knowledge in electronics—from piecemeal courses in robotics and a residency at SparkFun. “I’m definitely approaching this from a totally different way than a lot of people with an engineering background might approach it,” Keim says. “What’s nice about coming from an open-source electronics world with my projects is knowing that all of this information is out there for you, and a lot of people are there to hold your hand.” In addition to SparkFun, Keim cites Adafruit, O’Reilly Media and Make: magazine as key resources for this work. And to keep the knowledge flowing, he publishes the blueprints to each of his interactive projects on his website, allowing anyone with a beginner’s knowledge of electronics (and access to a machine lathe) to build the designs themselves.

While Keim already has new ideas for improving the piece, the designer views this object as just one step closer to the next prototype. “One of the best pieces of advice I got from the people I work with is that a project never has to be finished,” Keim says. “It can continually improve; you can always step back and look at it. You can take that to a point of insanity, sure, but you don’t ever have to think that your object is done. You can always make it better if you want to.”

This post was originally written by Carly Ayres for Core77

One of the longest surviving Mexican tribes to get its own videogame

Preserving the Rarámuri culture through a videogame.

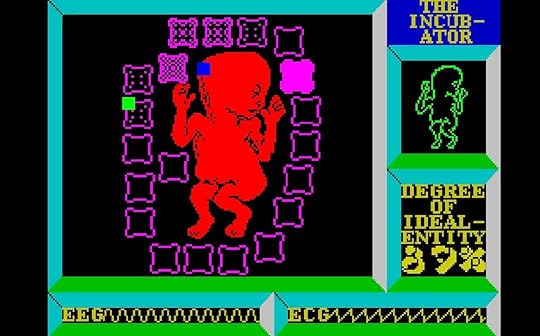

Deus Ex Machina: The 30-year-old arthouse videogame that time forgot

Perhaps the most remarkable aspect of Mel Croucher's Deus Ex Machina is how unremarkable it is. Although, that's not quite true. Created way back in 1984, it's among the first videogames to give rise to the "is it a game?" debate, while its author asserted its position as a piece of art and an "interactive film"—two concepts that had yet to be explored at all.

When it was released 31 years ago, it came spread across two chunky cassette tapes; one containing the game code, the other its soundtrack. And this soundtrack wasn't only a sequence of music: it was fully voiced by British icons Jon Pertwee, Ian Dury, and Frankie Howerd. So that's Doctor Who, an influential punk rocker, and an actor whose puckered-up face was the portrait of cheeky British comedy for a time.

"I thought I'd be generating emotion."

But Deus Ex Machina's format—a surreal, hour-long journey from womb to grave adapted from Shakespeare's play "As You Like It", about our insignificance and the impossibility of living a perfect life—isn't anything special. It could have been if it had arrived at another time. As Rob Fearon remembers, back in the mid-'80s, Deus Ex Machina spawned when people were "still very much trying out what videogames could be." Of course, certain tropes and trends were emerging even then, such as shooting spaceships and soldiers, and jumping across pits and racing fast cars. But this was before the time that huge companies attached their rudder to the medium to guide it towards marketable formulas to sequelize for profits. Videogames were still a new enterprise in the emerging electronic future. They were thoroughly experimental.

So Deus Ex Machina was another stitch weaved into the embroidery that videogames at the time formed as a whole. And any of these threads could have been the future of the medium, including the arthouse, semi-philosophical style that Deus Ex Machina proposed. Croucher, the game's creator, certainly hoped that would be the case as he was disappointed by the state of videogames by that time. In 2013, Croucher told Polygon that "[b]ack in the '70s and certainly by the time we hit the '80s, I thought I'd be making interactive movies and doing full stories. I thought I'd be generating emotion." Deus Ex Machina was Croucher's way of addressing this disappointment in videogames, and was meant to found a way to further his interest in exploration (metaphysical or otherwise), rather than the destruction of the arcade games popular at the time.

Of course, Deus Ex Machina didn't spark a trend, and despite being critically lauded (notably, videogame magazine Edge said of it that "Some day all games will be something like this") it only managed to break even. That came down to its marked-up price necessary to include a poster and fancy packaging. It was a business decision that cued Croucher's exit from videogames.

its familiarity to us now shows how ahead of the curve it was back in 1984

We're now in a time when digital tools have been considerably democratized. This has meant that more people are able to realize their own small videogame projects. The result is a number of games that are concerned with addressing a range of emotions and forms of interaction. It's a big difference when compared with the corporation dominated '90s and '00s, which meant companies such as Microsoft, Nintendo, and Sony acted as gatekeepers to the medium to an extent with their respective consoles. Now, with widespread mobile gaming and the increase in PC gaming, as well as more relaxed publishing policies on consoles, we're enjoying a wealth of interactive experiences.

And so, Deus Ex Machina's 30th anniversary package arrives among all of this, containing a director's cut with new graphics, and a re-release of the original. It slips quite seamlessly in among these other experimental games on, for example, itch.io's store page. This is why it seems as unremarkable as it might have done 30 years ago. And, really, it's a positive assessment to make, at least in terms of the state of videogames at these two separate moments in time. It acts as our connection between now and then, a bridge across the commodification of games that emerged in between. It exists as if a time-traveler who left the '80s and took with them their forward-thinking ideas, to re-appear now to resurrect those same concepts at a time that they may be further explored, realized, and appreciated.

Playing it now, it's hard to ignore how portentous and obvious Deus Ex Machina's messages feel. This isn't a negative take, as its familiarity to us now shows how ahead of the curve it was back in 1984. It adapts the videogame convention of having multiple retries into a reflection on the preciousness of our finite mortality ("Your life is expressed as a percentage score."). It's similar in its stance to how the game notorious for only letting you play it once, One Chance, is modeled, and that wasn't released until 2010.

Likewise, the way it stands so explicitly against the idea of enjoying violence in videogames is reflected in flawed form in the punch-drunk inversion of player-led violence in Hotline Miami, and its ilk (Spec Ops: The Line being the oft-cited example). And its musings on the mechanical body and machines disobeying those who created them has flashes of the brilliance seen in many a cyberpunk fiction. Yet it arrived before a lot of the sci-fi sub-genre really took off in popular media, with Neuromancer, Blade Runner, and Ghost in the Shell.

If nothing else, Deus Ex Machina is a forerunner that exists to remind us that, actually, many of the supposed new ideas emerging these days are but ghosts of what has come before. Unfortunately, and this is the tragic part, the way of tech-based and entrepreneurial industries is to move forward and forget the past. This is why, for the most part, Deus Ex Machina has been forgotten. Perhaps before we can truly have any progression in the videogame space, then, we need to get better preserving its history and celebrating its more experimental works.

You can purchase Deus Ex Machina on itch.io, the App Store for iOS, and Amazon for Android.

The lucid dreams of Cylne

Can a videogame be a poem? Does it matter?

Why does this art smell like fish?

For art, smell is the alternate VR

20XX, or, the limits of esports

Super Smash Bros. players have envisioned the death of the game.

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers