Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 263

June 11, 2015

These robots aren't here to kill you, and even if they were, they would just fall down

We are nowhere near Terminator's Judgement Day yet.

Astaeria turns classic poetry into videogame worlds for us to wander

The best poetry alludes to a kind of magic. After all, as one classic tweet had us recall, the act of reading is to "stare at marked slices of tree for hours on end, hallucinating vividly." It seems a bizarre activity when worded as such, but it's the truth, as the power of finely tuned stanzas is enchanting. They can transport us to other places, acting as a catalyst for imagination, emotion.

A less graceful method for this transportation, you might argue, is videogames. They, too, take us someplace else where we can play in ways we typically cannot. Rather than solely using the potency of words, the videogame recipe is one of interaction, visuals, and sound. With this comparison, Emma Lugo's ambition to bridge the gap between poetry and videogames doesn't seem so far-fetched. In fact, it can be swallowed as an act of logic to assume that the two mediums could link hands, and with only the slightest of pushes.

The words becomes worlds.

But Lugo is made of more than ambition. She has achieved. With a piece of software she calls Astaeria, Lugo has married her favorite poems with procedurally generated virtualscapes for us to explore. The words becomes worlds. At its menu, it gives you a selection of poetry to choose from, including classic entries by Sylvia Plath, Lewis Carroll, and T.S. Eliot. Next to these titles, rather handily I'd add, is listed a duration in minutes, so you know exactly how long it will take to experience the world inside.

Beyond that interim, each poem you select then billows into a surreal world of vivid colors that wash over the screen like waves, changing in hue as if a psychedelic tapestry. The solid parts of the world that you stand and jump on are geometric structures that curl up to your feet as you step forward, almost as if you're looking through a fish-eye lens. All the while, the verses of the poem appear in order for a few seconds at a time at the screen's center. Eventually, the world crumbles, whole towers and staircases of cubes falling away as the words take you to the poem's end.

Without the knowledge of how this virtual world is assembled, Lugo's effort to tie poetry and videogames may seem perfunctory. It appears clumsy: the text of a poem is overlaid on a videogame world—where's the great marriage of mediums in that? But it's more of a cocktail than it first appears. "The random level generator seed is set to the hash of the poem, and each tall, cubic structure corresponds to a line in the poem, with each cube component being sized according to a word in the line," Lugo explains.

So it is that the poem takes a physical form inside the software. Reading the words as you wander, you can imagine the structures as arches of stone, lakes of voidspace, and caves where creatures corral for warmth. Whatever the poem triggers you to hallucinate can dress this bare bones geometry. If you're reading Lord Dunsany's poem Charon, about the ferryman on the River Styx, perhaps you'll see the endless drops all around you as the deathly river itself. Or maybe the environment twists into fingers of rock where an unspeakable creature lurks if you're experiencing Lewis Carroll's Jabberwocky.

It makes sense that Lugo should leave detail out in this way. Poems do too. What's important is that there's space left for us to fill as that's where our mind expands the most. Take one of the most powerful short poems as an example: it's Nobuyuki Yuasa's translation of Matsuo Bashô's famous Old Pond haiku, and it goes like this:

Breaking the silence

Of an ancient pond,

A frog jumped into water —

A deep resonance.

You can purchase Astaeria for $5 on itch.io.

Talking to the monsters in Destiny���s House of Wolves

Can Destiny’s disconnected lore be resolved by its newest expansion?

Prepare to question unreality with SOMA's machine-horror on September 22nd

"Reality is that which, when you stop believing in it, doesn't go away.”

- Philip K. Dick

Humanity's centuries-old attempt to understand our own consciousness, from philosophy to biology, can basically be summed up by one single image: a dog trying to chase its own tail. From Descartes's declaration that, if nothing else, "I think, therefore I am," to the modern philosophers of the mind who now doubt the absolute truth of that statement, time seems only to get us further away from any definite answers on the matter. But, if it's any comfort at all, I don't think you need to be too worried about the possibility that you're just a brain in a vat somewhere receiving electrical signals from a computer to make up your current reality. Because, all things considered, this simulation isn't half-bad. At least, not half as bad as it could be.

For example, you could be stuck in a simulated reality like Frictional Games' upcoming SOMA, instead. In SOMA, you wake up as Simon, a man trying to survive an underwater research facility that—for some reason—has gone dark (spoiler alert: if any remote location in a videogame has "gone dark," don't expect it to be because of a party or power outage). As evidenced by the 12-minute gameplay trailer released just last week, the machines might have something to do with it, since they developed consciousness and started believing themselves to be human.

The E3 trailer released today provides only more hints about the thematic underpinning of this sci-fi horror. Displaying some Stockholm syndrome-like behavior, Simon appears to thank his machine kidnappers—you know, for making his life (or simulated life) feel worthwhile with all that death and hopelessness. The game's official website also hints at some interference from "alien constructions," so, if the evil robots don't get you, the evil robot-aliens will do their best.

making his life (or simulated life) feel worthwhile

As with Simon's own experiences, its hard for viewers to tell exactly what is real and what isn't in all of SOMA's promotional materials. Is this really Simon speaking, or is he just a robot who thinks he's Simon? Are the robots actually human brains-in-a-vat or just artificial intelligence gone haywire? And most importantly: why is that enormous, Big Daddy-esque alien monster running at me with all his might when I have only my wits to defend me?

All these questions and more will be answered on SOMA's September 22nd release date, coming on PC and PS4. You can explore more of SOMA's world through the official website.

The connection between IRL parkour and videogames

The real-life drama behind the Toronto parkour scene.

June 8, 2015

If you think hide-and-seek is child's play then you haven't played Badblood

Search and destroy.

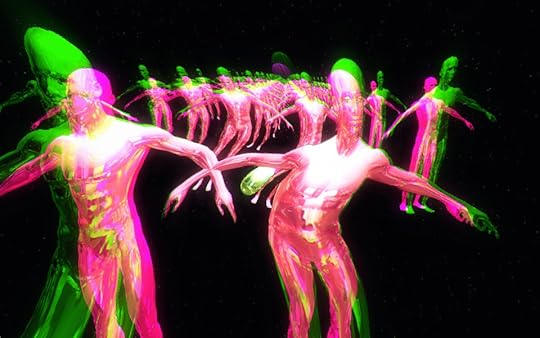

The deformed, lonely bodies of Kyttenjanae's colorful worlds

Kyttenjanae depicts loneliness and sickness in an unusual way. It's almost always as a rainbow-flavored mix of gross-out and grace. The signature animated art that she shares on her Tumblr page is recognizable for the eyeless humanoids that ebb and flow as if made of pink and polychromatic liquids. They strangle themselves and puke out their sherbert innards from mouths and arse, some hang limp out of computer monitors, or see their bodies morphed by a technological ripple of neon lacquer paint. Whatever the case, they're all forever trapped in endless torture by the looping gif format.

sick with consumerism

Her work has the shocking taste of Cronenberg's explosive body horror, yet Kyttenjanae transports it to a universe where it gets smeared in pastel paints and coated in gummy candy. It's an odd mix but one that might make sense. If anything, Kyttenjanae's work seems to be an idiosyncratic spin-off of vaporwave. We understand vaporwave to be an exploration of the hyper-capitalist aesthetic of the 1990s and its rich tech-futurism symbols. It's all spinning dollar signs, Windows 95, and low-poly models drenched in the language of the super rich—palm trees, "paradise," Greek busts, and gold chains. All of this is rooted in the corporate commercialism we see around us even today albeit with its hi-tech enthusiasm and pristine artificiality ramped up to a euphoric high realized in luxurious pinks and purples.

What vaporwave seems to envision is an accelerated virtual world in which only the shiny symbols of advertisements, money, and consumer technology remain. Yet, as awful as that might sound, the bright colors and glittering visuals of vaporwave make this appear as a utopia. Kyttenjanae seems to take this outlook but instead of focusing on non-human subjects, as vaporwave does, she visualizes what would be left of us in this tech-futurist world. According to her, we're lonely husks, separated by the technology that's supposed to bring us together, sick with consumerism and seeing our bodies helplessly morphing and frazzling. One gif of a spinning iPhone with the word "Alone" printed across its screen is perhaps the best icon for her entire work.

But Kyttenjanae's art isn't tied down to the format of the gif. Being a multimedia artist, she has expanded into video work, websites, and videogames. She's been able to show off this spread of talents more readily as of late due to a new website design. In conjunction with this relaunch she publicly released a game of hers called Apoptosis that she has previously shown at Holographic 2014 and other live shows and concerts. Now it's available to download for Mac or to play in your browser.

an act of transgression in other videogames

As you'd expect, Apoptosis fits under the pall that covers the rest of Kyttenjanae's usual themes, including death, mental health, remorse, and belonging. "I did my best to talk about an ongoing struggle to find purpose and place both internally and externally," Kyttenjanae writes about the game. To this end, it's a multi-part journey, with each leg taking you through different abstract structures—houses, lakes, and mountains—in what seems to be a desperate search for a place to call home.

What's most striking about it is the desperation at the heart of the game's exploration. This is most obviously realized in your inability to control the camera. You're at the every command of the camera as it slowly turns to face the way you point the character. And so, as you search out the environments, you're forced to do so in a painstakingly decelerated manner. It brings an appropriate sense of stress to the whole ordeal as your searching gaze can never keep up with your desire.

This desperation manifests in other, more authored ways, too. At one point you have to almost break the game by running over its steep barriers to progress to the next scene. If you don't fight your way over and beyond these walls then you'll be trapped in a valley forever. Hopping over terrain in this way is an act of transgression in other videogames but here it emphasizes how your search for belonging requires breaking pre-established rules.

You also transfer between different avatars throughout the journey as if trying on different bodies to see if they fit. Your default model seems to be as a skeleton that begins by running through literal walls of texts that imply they've lost a lover and must pursue them. But a more fitting idea is that this skeleton has lost its flesh and skin, and its this missing body that it searches for. After all, without the meat upon its bones this skeleton lacks an identity, meaning it isn't able to match itself with any of the bodies (which all do have flesh) it meets along the way.

After riding a pill across a lake dotted with palm trees the skeleton eventually finds tranquility in a holy temple surrounded by golden statues and dancing skeletons. It's here that it commits itself to the suicide that the game's title alludes to. It's an end that finds happiness only in the revelation that perhaps loneliness is the only partner for some.

You can find out more about Apoptosis and find links to download and play it on its website.

Body Trouble

The science fiction film Ex Machina falls into the uncanny valley.

Goldi mixes fairy tales and political philosophy, because why not

At the time of his death in 1527, the political philosopher Niccolò Machiavelli had never stated his position on works being placed in the public domain. Fair enough: “public domain,” as presently constituted, was not an idea in Machiavelli’s time. One can, however, suspect that the author of The Seven Books on the Art of War and The Prince wouldn’t have been big on the concept. Seeing as Machiavelli died nearly five hundred years ago, though, he has little say on the matter.

Thus, along with the fairy tale Goldilocks and the Three Bears, Machiavelli’s The Prince appears in Ed Curtis-Sivess’ Goldi, which was created for the 2015 Public Domain Jam. At first glance, this might seem like a strange pairing. It remains strange upon further glances.

Here’s how it works: You play Goldi in the first person, entering the three bears’ home and selecting some items to play with. Porridge—too hot, too cold, or just right—is, of course, an option. After a while, the family of bears return home. You hide. Papa Bear walks into the house, reciting a quote from The Prince. He then discusses the missing porridge with his wife. Shortly thereafter, Papa Bear discovers you, and asks a question that often references The Prince. Answer it correctly and he predicts great things for you, before drawing the game to a close. Answer incorrectly and you get to play again.

Fairy tales are rarely static stories; they are passed on orally, evolving with time. Nor, for that matter, are fairy tales expected to be wholly true. In that respect Goldi fits perfectly into the fairy tale tradition. It is respectful to previous stories, but not dutifully so. Maybe in 2015 the most apt version of Goldilocks is an extended intellectual property gag.

Goldi fits perfectly into the fairy tale tradition.

The story you know as Goldilocks isn’t even the original version of the fairy tale. (Original is a tricky word when you consider that fairy tales aren’t always passed down in writing.) An earlier version of the tale, The Story of the Three Bears, involved three bachelor bears and an old woman. That earlier work about bachelor males probably pairs better with Ayn Rand’s Atlas Shrugged, which won’t enter the public domain until late in this century. (And oh what an amusing day that will be!) Until then, lovers of fairy tales and philosophy have Curtis-Sivess’ Goldi, and that should be more than enough to keep them happy.

You can play Goldi for free on itch.io.

The Music Machine excels in silence

A surreal, Eraserhead-like examination of guilt and terror.

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers