Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 256

July 1, 2015

Robotic Latte Art: Very accurate and a little bit creepy

Your caffeinated beverage is, in all likelihood, milk with a side of coffee. Less generously, it is a milkshake. But what if your drink was something more than just the combination of espresso shots, steamed milk, and (heaven forfend!) pumpkin spice? What if your cappuccino was art?

This, in a demi-tasse, is the idea behind Ripple, an “internet of things” device that connects with an app to load images and then prints them in the froth on top of your latte or cappuccino. The device’s makers, an Israeli design studio-cum-startup called SteamCC, informed the Times of Israel’s David Shamah that it is a “foam printer.” Like a 3D printer, it can quickly churn out pixel-perfect images. A promotional video on Ripple’s site showcases a portrait of Miley Cyrus and a customized birthday message. “The entire operation takes about ten seconds,” SteamCC’s CEO Yossi Meshulam told the Times of Israel.

Traditional latte art can be produced either by carefully pouring milk to achieve popular shapes like hearts, leaves, and swirls, or by etching more complex patterns into the foam using small devices. Etching adds a layer of intermediation to the process of making a latte that Ripple multiplies exponentially. Even without Ripple’s technology, latte art can get plenty complex. In fact, there are national latte art championships that lead to the World Latte Art Championship. The latter competition states that participants are judged on “visual attributes, creativity, identical patterns in the pairs, contrast in patterns, and overall performance.” There are complicated score sheets for both the visual and technical aspects of the job. Even eye contact is measured. And for all that work, the results are necessarily and inevitably ephemeral. We know that Australia’s Caleb Chan won the 2014 World Championship with a score of 373.5 in the final round, but we’ll never be able to experience the art he produced that day firsthand.

The question with Ripple, as with most art-producing technology, is whether it takes the romance out of the enterprise and, if so, to what extent does that matter? Ripple’s demo video includes footage of a barista handing a man his latte with the inscription “Good Morning MATT!” etched into the foam. (Just imagine what Starbucks’ baristas could do if given the power to etch something vaguely resembling your name into your drink.) The text is printed in a crystal-clear typeface, which is helpful and a bit off-putting, like being asked how you’re doing by a total stranger. The beauty of the gesture is entirely dependent on its context.

Do robots take the romance out of the enterprise?

It may however be possible to get past the context and appreciate the foam printer’s output. As Julian Baggini notes in his Aeon essay “Joy in the Task,” Nespresso pods are increasingly common in Michelin-starred establishments in England and France. Pods, by many accounts, produce a more consistent result. So much for romance. “The logical consequence of molecular gastronomy,” Baggini argues, “is haute-mechanisation.” How else is perfection to be achieved? Ripple takes the logic of Nespresso pods and sous-vide cookery to the next level by mechanizing its visual presentation. Insofar as it brings latte art within the reach of those who cannot visit Caleb Chan or his peers, Ripple uses mechanization as an egalitarian tool. The cost of this equality, however, is sameness. This is why the Mona Lisa in your doctor’s office and the Mona Lisa in your other doctor’s office are somehow less compelling than the original. As Baggini concludes, “Humans are imperfect, and so a world of perfection that denies the human element can never be truly perfect after all.”

June 29, 2015

The satisfying mundanity of Cradle's science fiction

Today's wonders are tomorrow's chores.

Apps are the best hope for Moscow's architectural heritage

You never know what you’ve got until it’s gone. So it is in Moscow, where on the occasion of the Garage Museum of Contemporary Art’s unveiling, the architect Rem Koolhaas told The Guardian “you can say so many things about the Soviet system that were bad, but in terms of public architecture it was generous.” Much of that architecture is now gone, as is much of the architecture that preceded it.

Archanoid, a mobile app created for the Russian website Meduza, attempts to make this loss feel tangible. Based on the classic arcade game Breakout, Archanoid asks the player to bounce a ball of bricks. The ball, it turns out, is effectively a wrecking ball; each block represents a building that has been demolished. As blocks are destroyed, information about the corresponding building appears at the top of the player’s screen. Further information about these buildings can be found in Archanoid’s encyclopedia, which contains images and details about hundreds of buildings. “As you tear through each level,” writes City Lab’s Kriston Capps, “you rack up special achievements, including parking lots, replicas, a bulldozer, and Yury Luzhkov’s famous cap.”

Architectural heritage is increasingly preserved via this sort of technology. The New York Public Library’s OldNYC project, for instance, serves as a sort of historical Google street view, allowing you to see what an intersection looked like at various moments in time. Likewise, public historians are now using geolocation in projects such as Histories of the National Mall to provide a glimpse of what was once there. Archanoid is best understood within the context of these efforts to give a sense of immediacy to architectural heritage.

"No other capital city is being subjected to such devastation for the sake of earning a megabuck.”

Unlike its American cousins, however, Archanoid is responding to a more urgent situation. In 2014, the Moscow Architecture Preservation Society issued a report that declared: “There is no other capital city in peacetime Europe that is being subjected to such devastation for the sake of earning a fast megabuck.” This is one of the many costs of Moscow’s transformation into a capitalist mecca. And while growth and development usually requires the destruction of some history, in Moscow the desecration of patrimony appears to be out of all proportion and know few restraints. Last year, Moscow’s municipal government staged a virtual referendum on development, asking residents to use an app and vote on the future of the Shukhov tower. Ninety-one percent of the app’s users voted to restore the early 20th century gem in its current location. Moscow’s app is saving a small part of the city’s rich architectural heritage. For hundreds of buildings that have already been destroyed in the name of expediency or building a shrine to petrodollars, there’s Archanoid.

How Beyond Eyes went from a beautiful student project to one of the stunners of E3

Exploring the gorgeous, painterly world of Beyond Eyes with creator Sherida Halatoe.

Forget Jurassic World, here's a game with a badass red-headed dino hunter

As we've seen in Jurassic Park, and now Jurassic World, the unstoppable force of a hungry dino can only be thwarted by one thing: cool, overly confident badassary. Whether its Sam Neill battling a car and a raptor at the same time, or Chris Pratt's motorcycle sequence, the more outlandish your survival tactics, the more likely you are of conquering the dinosaurs wanting to make a scratching post out of your flesh.

the dinosaurs wanting to make a scratching post out of your flesh

But, really, the protagonist of Theropods tops all other dino-themed badassery before her. In fact, I'm pretty sure this fiery-haired cavewoman would pick her teeth with Pratt's bones as much as any one of his misbehaving raptors would. Because this protagonist, unlike those others who encounter dinosaurs, lives in a world entirely populated by the beasts. They roam free, a constant threat to our protagonist's way of life—and her ruthless fighting style proves just how time-tested she is. Dinosaurs are such a normal part of her life that when two raptors decide to rush her peaceful campfire out of nowhere, our fiery redhead springs into action, scaling a tree and swiftly making her way back to safety by using the environment against her attacker.

The protagonist, who appears to combine Brave's Merida with Eep from The Croods, must rescue her witch doctor companion after saving herself. As a point and click game created in just two weeks for the adventure jam, Theropods is a quick trip into this redhead's cutthroat world. But each puzzle and animation emphasizes the huntress's craftiness, as she tries to make a home out of a hostile environment—instead of just survive the dino-hell her and her fellow man invented for themselves.

In the end, there are some brutal and depressing casualties to our fiery redhead's determination. Never before have I solved a final puzzle in a game only to go "Yay—Oh no! I didn't mean it! I take it back!" Despite how short Theropods is, it makes an impression and captures the day-to-day reality of being a true, badass dinosaur survivalist.

You can play Theropods for free here.

When will videogames be part of the cultural canon?

A college professor on the difficulties—and rewards—of teaching videogames.

June 26, 2015

Kill Screen is bringing our favorite stuff to Ace Hotel next week

Beat the heat at the Ace Hotel with drinks, music and games.

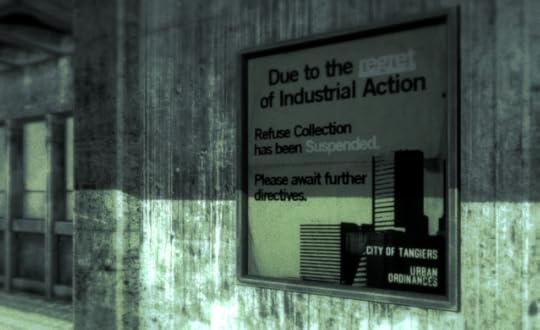

Tangiers turns the police into something straight out of a surrealist's nightmares

One of the first things I noticed about Tangiers was how quiet it is. In a medium populated by graphically noisy deaths, swelling soundtracks and the constant ding of coin collection, Tangiers' use of diegetic and industrial tones stood out. But while Tangiers promises to be a whisper compared to its peers, it certainly won't be voiceless. Boasting a dynamic 'words mechanic,' in which spoken language becomes a physical and interactive tool toward your goals, Tangiers makes literal the idea that the pen is mightier than the sword, as words become your weapons.

As the game nears its beta release, creator Alex Harvey is updating the development blog with more specifics about the stealth and action. In this surrealist, dadaist-inspired game of infiltration, your goal is to eliminate your assigned targets without raising the alarm. The world of Tanigers responds to your actions by re-assembling and collapsing dramatically. So, if you do raise the alarm, the next levels will be half falling apart, half filled with the whispers of your past mistakes from the area where you endangered the mission.

the only weapon at your disposal will be words

Andalusian, the studio creating Tangiers, introduced its latest enemy type during the latest blog update, calling the super efficient and robustly programmed A.I. 'Trained NPCs.' They're just like the standard "police" type figures but are much less forgiving and more relentless. "These characters will gather, take cover and surround your building. They'll set up some portable barricades and block off connecting streets. They'll pin your area down, and once they've all deployed the signal may be given for them to march forward, performing a systematic sweep of the location."

At this point, after alerting the trained NPCs, the only weapon at your disposal will be words. The physical manifestation of dialogue in Tangiers not only pays homage to Burrough's cut-up technique through aesthetic, but also doubles up as the final frontier of survival in these situations. So, let's say you left a body lying around in the open, or got caught by the security camera. Once the enemies start searching for the disturbance you can throw them off with a choice placement of a certain word. Depending on the word you put in place, you can either cause confusion, chaos, or just pure panic. Dropping a word like "rats" can even summon a swarm of them, allowing you to escape through careful improvisation.

The team also announced that, three months after they release the game officially, they will provide free level creation tools. Though there's no details yet, dreaming up the possibilities with a malleable and responsive environment like Tangiers proves to be an entertaining exercise. As a game inspired by improvisation and abstracting the subconscious, Tangiers should prove to be a breeding ground for odd and intimate modding experiences. "I'm super excited at us being able to do this and at the potential of seeing other folks' Fan Missions," Harvey says.

Tangiers is still a little ways away from releasing the beta, but you can keep up-to-date through its Kickstarter or its Steam page.

Everybody's Gone to the Rapture aims for "genuinely nonlinear narrative"

Everybody's Gone to the Rapture designer Dan Pinchbeck has written a long blog post detailing the game's creative genesis. Peppered throughout are some hints on what the final game—which, after being shrouded in secrecy, is due to be released in early August—might contain.

He's spoken before (to Kill Screen, among other places) about the "cosy catastrophe" branch of apocalyptic fiction, a distinctly British take on the end of the world focused as much on the quiet dissolution and retention of social norms as it is on, like, marauding bands of radioactive freaks. Here he pinpoints their appeal to the era:

The early 80s was a tense time to grow up – the cold war was looming over us, AIDS was suddenly not seen as a disease limited to gay culture and was sold to us as a civilisation killer (no accident perhaps that the threat of a ‘gay’ disease went hand-in-hand with the political shift of acceptance at the time), there was a dawning sense of ecological crisis. There was a fair amount of hate and anger flying around in society as a whole – Thatcher was targeting the unions and destroying whole communities, we went to war with Argentina, unemployment was massive and social equality was being trampled under.

Perhaps not coincidentally, the game is set in 1984. The "cosy catastrophe" works, particularly those of John Wyndham and the 1984 BBC film Threads, responded to this anxiety as much as they fed into it. Pinchbeck draws an interesting line between that genre and the term "walking simulator," the videogame sub-genre his early work Dear Esther is often credit with starting. "Both are derogatory terms that have been reclaimed by the people making them," he writes, "and that’s a nice turnaround for me."

Most interestingly, he contrasts that game, which was an hour-or-so jaunt through a bizarrely quiet world, with randomized audio sequences laid overtop, with his new work.

Dear Esther clearly worked, right… but it was linear, as is most game narrative. Especially in open world games, they were still essentially linear threads. You could explore the world openly, but then you’d lock onto a linear path and follow that. And I was wondering what would happen if you had genuinely nonlinear narrative – you could go anywhere, at anytime, and the story was just waiting there to be discovered? What if we pushed what was normally background narrative, environmental storytelling, into the centre?

The brief extended videos they released at E3 of the game being played show this in action—a wide-open world, full of nooks and crannies to explore. The Vanishing of Ethan Carter took a similarly unhurried, almost bucolic approach to walking simulation, but Everybody's Gone to the Rapture looks to take it even further.

The blog post, which is worth reading in its entirety, is here.

Videogames understand symbols, except when it comes to the Confederate flag

The Confederate flag: offensive symbol or just a distraction from the real debate?

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers