Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 235

August 27, 2015

Scale is exposing the challenges of scaling videogames

Scale is a puzzle game with a straightforward elevator pitch: “You wield a device that can make any item any size.” This is a popular pitch. It earned the game $108,020 in funding from over 5,000 backers during its Kickstarter campaign. Steve Swink, Scale’s creator, subsequently created an alpha version of the game and has now written about what he’s learned in an illuminating update.

Swink’s post helpfully addresses the challenges of scaling (excuse the pun) from a demo to an actual game. Things that worked in the former may not be as compelling in the latter. The growing size of a game normally calls for more things to do—playing an overlong demo is unappealing—but that growth can come at the risk of coherence. “If the grammar of the game isn’t carefully developed as the levels progress, lateral leaps of intuition will feel unfair,” Swink writes. “The player won’t be able to figure it out.”

Game design establishes a sort of language

One of the functions of game design is to establish a series of patterns—a language, of sorts—that players can easily understand and follow. The limited size of a demo makes it relatively easy to teach these patterns. You use what you just used. But as Swink notes, this process gets harder when it comes time to scale:

As a designer, I have a pretty good sense of what the player is thinking in the earlier levels - whatever they just learned they look to apply to everything. The thing I’m working on now is the later levels: if the player has 10 ideas, concepts, and mechanics in mind it’s harder to intuit what they might be thinking entering a given level.

Swink helpfully details the different ways in which this problem has manifested itself in his post, which you should read it in its entirety. The story of Scale, however, is not self-contained; many of Swink’s points could be applied to the videogame industry writ large. Last week, I covered the overwhelming success of tabletop games—both financially and in terms of satisfaction—on Kickstarter. One of the main factors in that success was the existence of a growing ecosystem to help developers take tabletop games from demos to products their backers can enjoy. The route from demo to finished project, as Swink’s post attests, remains more complicated for videogames. Videogame demos correspond less closely to finished products, thereby necessitating the kind of work Swink writes about. A pipeline for videogames like the one tabletop game developers discuss would be nice, but in the meanwhile, I’d happily settle for Swipe.

PSA: The Hitman movie is another truly awful videogame adaptation

The Hitman movie feels like it was based on the back-cover description of one of the games.

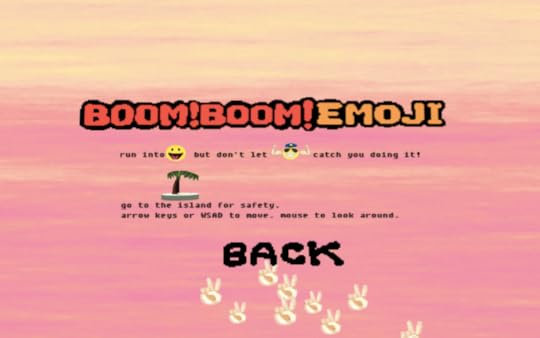

Here's a game that lets you wipe the smile off a stupid emoji's face

Some people like smiling at strangers and saying hello to passersby. Bless their souls, those creepily friendly weirdoes! I, as you may have guessed, am not one of those people. Nothing warms the cockles of my cold, dead heart quite like strangers giving me the “Fuck right off!” look.

As such, Boom!Boom!Emoji is my kind of game. It is a neon world populated with floating emojis and palm trees on islands. You try to make the smiley face emoji explode by running into them. If you succeed, they explode into firework-like constellations of flame emoji, which is really quite pleasing. Of course, this being a game and not just a form of anti-social wish fulfillment, there are some impediments to your quest to blow up all the smiley faces. More specifically, there are policemen, rendered as smiley faces with serious hats and biceps worthy of Popeye. Collide with a policeman and is game over for you. (That, as best I can tell, is the closest this work of art comes to imitating life.)

Is Boom!Boom!Emoji a horror game? Its smiley faces sure as hell scare me, but clowns scare other people and that doesn’t cause us to categorize them as anything other than light-hearted amusement. The same holds true with regards to Boom!Boom!Emoji, which functions as a sort of exposure therapy, granting players slightly more agency in a low stakes environment. Games cannot cure our fears, but they can make them slightly easier to cope with. Boom!Boom!Emoji isn’t therapy in any traditional sense, but it works.

The return of Dishonored

The fiction and function of Arkane’s masterpiece.

August 26, 2015

Hyper Light Drifter gets a pretty, new trailer and (finally!) a release date

Hyper Light Drifter, like Rain World and a few others, seems like one of those games that exists only in shiny gifs on Twitter, so it comes as massively exciting news that Heart Machine’s mesmerizing action RPG finally has a release date.

That’s right! Hyper Light Drifter comes out Spring 2016 and there’s even a new trailer to gawk at.

Heart Machine launched a Kickstarter campaign for Hyper Light Drifter in September 2013. One trailer and a few gifs later, and Hyper Light Drifter spawned loads of games bearing its same bright, triangular art style and distinct approach to pixel art. The game isn’t even out yet, but its striking good looks manage to influence even two years later.

The music in Hyper Light Drifter (and this trailer) is by Disasterpeace, an electronic musician known for his work on the soundtracks for Fez and, most recently, It Follows.

You can pre-order Hyper Light Drifter, or learn more, on its website.

Lucas Pope's latest game replaces the evils of communism with the evils of capitalism

File some junk mail for the devil in Unsolicited

With Unsolicited, Papers, Please creator Lucas Pope turns his attention to corporate America

Lucas Pope, creator of Papers, Please, turns his bureaucratic attention to junk mail

Why is Rocket League's jumping so much fun?

Rocket League is a game that is concerned with a great many things, but verisimilitude is most definitely not one of them. To wit, here’s an excerpt from Psyonix president Dave Hagewood’s excellent interview with Gamasutra about the game’s jumping mechanics:

Designing Rocket League's rocket-boosting mechanic was an interesting process; because it was so much more emergent than other games that we've worked on. Usually, we start out with a very concrete plan of what you want to do, but in this case we really started out with just a very simple mechanic: cars that jump.

We like cars that can jump. We know they're fun to play with. Even in the earliest stages of development, it was just fun to drive around the map, and that’s when we realized that we knew we were on to something.

Before proceeding, I must stress that you should really read the whole interview. It’s glorious. Done? Ok, let’s proceed.

Rocket League is unhinged. It is the kind of game you imagine was invented in a dorm room after a couple bong hits too many. Yet “following the fun,” as Hagewood puts it, is hard work. You don’t simply throw a game out into the ether and have it magically turn into something fun.

In that spirit, Rocket League is a game with bonkers physics, which is crucially not the same as saying it has none. “I've always been a fan of real-world physics in games; rather than faking things behind the scenes, I prefer to keep the physics simulation as pure as possible,” Hagewood told Gamasutra. “So we literally just applied a force to the back of the car, since the car is also a physics object, to create this turbo boost.” Rocket League’s physics are not this planet’s physics, but they are physics nonetheless.

In that respect, Rocket League’s closest relative may actually be the Super Mario Brothers. The game had no obvious connection to reality, but jumping—its crucial mechanic—was still far from random. As Kill Screen supremo/founder Jamin Warren explained on PBS’ Game/Show, the jumping “had its own specific physics. … The distance Mario hops is determined by calculations of gravity and velocity.” This realization prompted Business Insider to try and calculate which planet Mario must be on to experience such gravitational forces. Not earth, that’s for sure.

Rocket League is not a car game in a traditional sense. It owes as much to Super Mario Brothers as it does Need for Speed. And that’s fine. It’s still fun. But work goes into fun, and Dave Hagewood’s explanation of Rocket League’s jumping mechanic is proof of how much structure underpins what we feel to be loosely structured play.

Welcome back to the old Internet. It had problems too

It is easy to pine for the old web. The past is in the past, temporally shielded from our attempts to fetishize it and incapable of reaching through the screen to knock some sense into its eulogists. This is how the nostalgia-industrial complex, the one sector that will never take enough of a pause for us to eulogize it, flourishes.

“Cameron’s World,” a project by Cameron Askin and Anthony Hughes, attempts to revive the joys of building a personalized webpage on Geocities in the mid-to-late 90s. The resulting pages are full of overlapping graphics, bright text, animation, and even music. “Cameron’s World” is, in other words, everything that made the old web simultaneously horrible and endearing. “There’s not a whole lot of ‘nice’ (or user-friendly) web design in [old Geocities sites],” Askin conceded in an interview with Motherboard, “but the archives are exploding with creativity.” This trade-off is also present in “Cameron’s World,” which is full of strange ideas and originality but also a violent attack on the eyeballs and mental faculties of its visitors. This is a vision of the web built for communities more than for human beings.

The organizational metaphor of the Geocities-era web was the neighbourhood, a place for like minds to share their views in relative peace. In his Motherboard interview, Askin discusses how he visited these neighbourhoods to find inspiration for “Cameron’s World.” He also notes “users were less critical of websites and creators had a less polished approach. … The tone of voice was a lot more personal.” Insofar as those features are arguably lacking on today’s web, it’s easy to understand why Askin and others would be drawn to the Geocities sites of yore.

A web for communities instead of human beings

One might therefore be tempted to argue that the old Internet was more democratic, a place where anyone could create a site in a safe corner of the digital world without worrying about the vagaries of web development or visual conventions. This sort of web design is, however, exclusionary in its own way. This sort of anarchic web is great for its denizens but inaccessible to those who depend on screen readers for their data or simply struggle with visual clutter. Subsequent visions of the Internet have sought to solve this problem, creating a web that is more structured and inclusive to some previously disenfranchised users, but doing so at a cost to those who enjoyed the anarchic verve that “Cameron’s World” recreates.

The Internet has usually sought to be democratic but has never figured out what democracy means in this context. Much as there are differences between the American, British, and French visions of democracy, there also differences between different conceptions of the democratic Internet. None are inherently more democratic than those that came before, but we often lack the vocabulary to parse these differing democratic visions. This is a discursive challenge that affects the videogame world as much as it does those interested in the future of the web. While all democracies exist to maximize enfranchisement, participation, and representation, there is always the question of what sort of engagement a democracy seeks to maximize and how it intends to achieve such goals. There is no single right answer. “Cameron’s World,” in addition to being a Technicolor trip into the Internet’s past, is a reminder that visions of digital democracy can take on radically different appearances.

Join us to celebrate great mobile games

Movable Play is driving the future of games.

Submerged finds boredom at the end of the world

For those who wanted collectibles in their apocalypse: here you go.

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers