Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 230

September 4, 2015

The Sharing Economy isn't about sharing

Sharing is largely incidental to what has come to be known as the “sharing economy.” It is simply a solution to the larger problem of allocating resources. Let’s say you have a possession—it doesn’t have to be a car or a domicile. Let’s call it a widget. You use it some, but definitely not all of the time. This is silly. You have paid for full-time ownership of the widget yet it sits dormant most of the time. Other people who want to use a widget will buy their own widgets and also use it some of the time. Assuming the widget is costly (a safe bet) and has environmental consequences (an even safer bet), this situation is suboptimal for anyone, whether or not they actually own a widget.

In theory the sharing economy solves allocative inefficiencies

This problem can be solved using some sort of sharing mechanism: you rent the widget when you are not using it; some other financial incentive is created to encourage you to use the widget all day and put it at the disposal of others. Fewer widgets should therefore be needed to fulfill the needs of more people. Thus, in theory, the “sharing economy” solves allocative inefficiencies.

But these inefficiencies exist because most of our widgets (undergarments notwithstanding) are designed to only be used some of the time. Sharing apps/services are not the only solution to this problem: one could also design things that are useful around the clock. That’s where Kent Larson, the director of the Changing Places research group at MIT’s Media Lab, comes into the picture. Politico Magazine has an excellent documentary on Larson’s work towards building denser, more efficient cities:

The two projects highlighted in Politico’s documentary—a self-driving tricycle and a compact, robotic domicile—operate along similar lines. Larson and his collaborators take objects that are normally used a fraction of the time and make them useful around the clock. The self-driving tricycle, for instance, is a more efficient bike- and ride-sharing system because the tricycles dynamically transport themselves to in-demand pickup spots. There’s no need for fixed bike-sharing stations and trucks ferrying the bikes back and forth. Larson’s vision of an apartment, meanwhile, uses all sorts of fancy engineering to fit all the functions of a home into a single, compact room. Every square inch is therefore constantly in use.

Larson’s vision of society goes against how the future of urbanism tends to be depicted in games. City builders like Block’hood, Polynomics, and Cities: Skylines all present urban environments as a series of plug-and-play modules. This mechanic is not inherently antithetical to the promotion of density—adding an expansion module on top of pre-existing modules maintains density by building up—but it leads to plenty of wasted space. Stacked spaces can still be wasteful. This phenomenon sheds a useful light on Larson’s work. Instead of fetishizing density, he is pursuing the broader goal of efficiency.

Sharing is not going away, but much of the logic of the “sharing economy” points to it eventually becoming a less important mechanism. Uber’s investment in self-driving cars, for instance, aims to make car ownership unnecessary and undesirable. Ideally, you will have no longer have a car to share. Sharing will still be necessary in other situations; no matter how efficient an apartment Larson designs, its space will still be wasted while residents are on vacation (Hello, Airbnb!). When it came to describing apps and their associated labor practices, sharing was never particularly a helpful term. Larson’s work helps to clarify why we might as well give up on the term entirely in favor of a sobriquet that accurately encapsulates the goal of having an economy (and society) where all things work 24/7. Please share your suggestions with Uber.

Glitchspace switches intimidation from its programming puzzles to its architecture

Using a programming gun to solve environmental puzzles is one of those ideas that works great in theory more than it does in practice. That's what Space Budgie discovered upon releasing the first alpha build of Glitchspace last year, at least.

Yes, despite the positive reception from early critics and fellow game developers, Glitchspace proved to be polarizing among the first batch of players. "Some were on board straight away with the developed programming mechanic, whilst others were left confused and alienated by a title that felt completely closed off to them," Space Budgie said.

it layers each programming idea on you

It makes sense that this would be the case. This is, after all, a videogame that has you dragging and dropping actual (if simplified) code. Not too many people are familiar with doing that. And it seems that what Space Budgie didn't manage to do was ease those who are completely unfamiliar with coding into all the lingo and mathematics that it requires you to understand. I didn't have a problem with it myself, but I'm aware that that's due to my time spent fiddling around with basic programming in Unity—any actual programmer should whip through the game without a hitch.

Having realized this error, Space Budgie has spent the entirety of 2015 so far creating what it calls alpha 2.0, which was made public yesterday. What it represents is a complete overhaul of Glitchspace's introduction. It doesn't assume that you know what to do with vectors and 'if' statements right off the bat. Instead, it layers each programming idea on you, letting you test it out in a safe space first and then in a more dangerous scenario afterwards.

It's game design 101 but, hey, it works and it means that Glitchspace picks up its momentum much quicker. In the hour that it took me to get through alpha 2.0 I went from basic programming tasks such as making platforms solid so I could walk on them across a gap, to tweaking complicated sums so that a platform launched me hundreds of meters into the air to land elegantly inside a fractured cathedral.

Mondrian's reduction of form and color to simple shapes is used

And that's another thing that's changed: the architecture. The first builds of Glitchspace only had flat-looking blocks populating a sparse topography. Now it feels like you're navigating the frozen aftermath of an explosion that has sent whole pieces of carved masonry into the air. Windows cast criss-crossing shadows across the floor, stacked staircases lead up to inviting portal gates, and the floating platforms you ride could be part of a robotic assembly line. You get a sense that the fragmentation of the game's glitch theme extends beyond its puzzle mechanics and further into the world itself, which you may or may not be piecing back together.

To achieve this, Space Budgie says that it has taken from the classic abstract artworks of Mondrian. It's hidden like a ghost, but you can see faint traces of Mondrian—and more specifically neoplasticism—in the walls that are patterned with grids of black lines, as well as the selective use of color across all the structures. It helps that the geometry you can reprogram is colored strictly in a bold red while everything else belongs to the glowing tones of cyberspace too. Here, Mondrian's reduction of form and color to simple shapes is used aesthetically and practically so that it's clear what you can interact with to move forward.

The finale of alpha 2.0 goes beyond this. It manages to build in a verticality that steadily creeps up on you. As you leap further upwards using the launch platforms you reprogram, the arches and staggered brickwork of Gothic towers is drawn in, implying a greater theme of celestial height. Until, eventually, you reach the top, where staircases cannot go, and have to fall all the way back down through a transparent pipe, noticing the gradual shift from sunshine to purple darkness.

The biggest difference between the different alpha builds is a sense of story (appropriately, considering it now has a Story Mode). It's found in the how the architecture evolves as you climb and descend. But also on a more basic level as you warp between each separate area, learning a new programming trick—and properly learning it this time—building a toolset that you can tell is leading you towards some greater task.

You can purchase Glitchspace from the shop links on its website.

A board game about Indian colonialism from the creators of Somewhere

Even in board game form, games by Studio Oleomingus are simply mesmerizing. The team behind Somewhere, a surreal stealth game set in an alternate world version of colonial India, have started work on an unnamed historical project about running a Portugese colony in 17th century Goa.

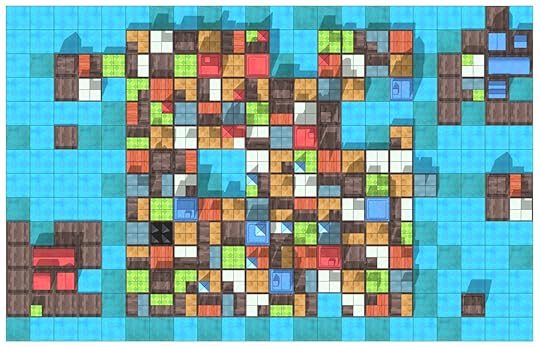

In a recent post about the project, Oleomingus provides a series of mockups detailing their German-style board game influences and diving into how the game works. The map is dotted with vibrantly colored squares, representing the majestic palaces you’ve built up and the different resources there are to extract: cotton, wood, gold, grain, and gunpowder.

“nefarious shenanigans” related to colonialism

Presumably the gunpowder is something you manufacture, but coming from the folks behind Somewhere, where toothbrush forests and enormous oil lanterns are the norm, I wouldn’t be surprised if it’s a mineable resource.

Since this is a colony, mining too much on one square can cause the labor force there to rebel. The specific mechanics of handling this and other aspects of the game are unclear so far, but Oleomingus makes mention of securing trade routes, managing local interests, religious conversion, and other “nefarious shenanigans” related to colonialism.

An artist named Gayatri Kodikal is working with Studio Oleomingus on the game, which is also being supported by the India Foundation for Arts and the Archaeological Survey of India, so much of this will be rooted in the real medieval history of the western Indian state of Goa.

Check the Studio Oleomingus blog for more on their board game and Somewhere .

Feeling Alone in Everbody's Gone to the Rapture

Who are you in Everbody's Gone to the Rapture?

Wrangle produce and fight off corporate greed in Chesto

In the United States, we tend to get wrapped up in our own abhorrent capitalist practices because, well, we're the best at it. But we forget that ruthless capitalism is a world-wide disease, infesting the planet with hypocrisy and Marxist nightmares. Tesco, a supermarket chain ranked as the 2nd largest retailers in the world, encapsulate the evils of capitalism in the UK, with humanitarian issues ranging from selling their customers horse meat to failing to pay their workers minimum wage that gets subsidized by tax payers (costing them an estimated £364million last year).

Tesco has been at the the center of the UK's debate over living wage since the government adopted a plan to raise it from £6.50 an hour to £7.20 for those over 25. Implemented to mitigate the government's significant cuts to welfare, some reports have found that rather than helping lower income families, the new policies will actually cost families hundreds (if not thousands) per year. It would appear the Conservative party has attempted the play the old switcheroo trick on the UK's population in a national game of Find the Lady where, instead of finding the queen playing card, you're trying to survive and have enough money to eat.

But big corporations like Tesco don't need government help screwing over their workers. They already do plenty of that on their own. Because while the supermarket giant refuses to pay its workers the basic cost of living, they send their failed executives off with £1.2 million lump sums and a pension of about £14million. The company's policies have been so egregious, in fact, that even shareholders are raising a fuss. Presumably more concerned with the supermarket chain's record annual loss of £6.4 billion this past year, shareholder Michael Mason-Mahon attacked the board at a meeting back in July. The Daily Mail reports that he went as far as to call Tesco "a cancer on our society because you keep the poor, poor. This is not right. Slavery was abolished… The new slogan should be 'Tesco: we do not pay Living Wage but we do reward our executives for failure and make them multimillionaires.'"

"This is not right. Slavery was abolished"

Though Tesco's antics are depressingly flagrant, they are in no way surprising. As customers and citizens, we know that when we shop at Tesco or Walmart in search of those scintillatingly low prices, we also take part in a larger evil. The price we pay as customers is less monetary and more ethical, giving up pieces of our soul for discount chicken (which is probably discount rat meat). Meanwhile, the person scanning and bagging your rat meat pays an even heavier price, forced to work for the company not out of choice or the promise of low prices, but out of necessity. The measly wage companies like Tesco provide their employees not only leaves them in horrible living conditions, but also wears on their very spirit.

In the voxel world of Chesto, you play as a cashier working checkout at a large supermarket corporation with some familiar-sounding employee policies. Everything about the design of the checkout mechanic is cumbersome: the food drifts off, floating away from your grip; you must scan every single item individually (meaning you must find the tiny little bar on every strawberry); all the while corporate and a timer at the top of the screen are breathing down your neck. While you scrimp and scramble trying to reign in all the food bouncing around the conveyor belt, corporate likes to pop in to assure you that it will not be paying overtime for the work you don't finish in the allotted hours. Customers prove equally unsympathetic, commenting on your slowness and raising a fuss when their runaway cucumber lands on the floor.

At the end of each day, you're given a report of your measly earning which is always "just barely a living." Unless, that is, you're fired altogether for "costing the company too much money." Meanwhile, Chesto boasts the amount it made off of your hard day's work by directing you to the corporation's website. They're nice enough to demonstrate clearly just how much you're helping their numbers soar, implicating you in their capitalist super villainary. But, Chesto's website assures, this is a company who "can always be trusted to do the right thing" and only "employs the best people, develops their competence, provides opportunity and inspires them to live our values."

The creators (Josef Wiesner, Felix Bohatsch, and the Broken Rules studio) don't specify how they calculated the profit margins featured on the graph, but their accuracy in recreating the average wage of a Tesco employee most likely indicates their numbers are depressingly close to reality. The more players that log in hours working at Chesto, the more their numbers grow. They've even got a phony voxel CEO, pictured in all manor of luxury like sitting behind Nicki Minaj at a fashion show or taking red carpet snapshots with Kim Kardashian. What was the new slogan that Tesco shareholder suggested? Oh right: Chesto, we can pay you minimum wage, but we do reward our executives for failure and make them multimillionaires.

You can play Chesto online for free on Mac, PC, and Linux.

Mario: A Memoir

We relate to each other through culture—until we can’t.

Brave a blizzard in The Howl and find something worth hunting

I didn’t find the monster in The Howl, but I knew it was there: a looming silhouette out in the blinding white of the forest’s sparse horizon. I’d get a glimpse in the corner of my eye and ready my bow, but then the violent winds would start up, casting a layer of snowy fog to obscure my vision again.

Braving the blizzard only gets me more lost than before, but standing in the shelter of a dead tree until the calm returns puts more distance between me and whatever it is I’m hunting. I have to keep moving, collecting more arrows, practicing my aim on the snow rabbits that cross my path, keeping an eye on the colorless horizon for that fleeting glimpse of movement that draws me onward.

I’m starting to think this is all in my head, that there really is no beast to track and that the blinding whiteness is just playing tricks on my eyes, but I return to The Howl anyway for its atmosphere and tension. It reminds me of Vlambeer’s Yeti Hunter, which is set in an equally desolate, frozen wasteland, though I’m not sure if I’m also hunting a yeti in The Howl, and even less sure of how to find whatever it is I am hunting.

Getting around is the hardest part. Strange landmarks dot the forest, from crossroads signs and Blair Witch-esque stick sculptures, to tall stone monuments and what seems to be the remnants of a cabin, only a wall with its window frame in tact, but none of them help me on my way.

I’m drawn back to The Howl

The only thing I can really rely on for direction is the way the wind blows, carrying flakes of snow with it, but even then, I get turned around so often that it’s possible not even this is consistent.

Still, I’m drawn back to The Howl. It’s a bit buggy, but its slow pace and the long stretches of land to cover make even its smallest discoveries feel special, and the idea of finding that elusive creature even more so.

Download The Howl on its Ludum Dare page or itch.io for free.

Tearing the Fabric

Some psychedelic implications of Super Mario World.

September 3, 2015

In how many ways is Varg Vikernes's white supremacist game the worst? Let us enumerate

Where, if anywhere, is the line between casually offensive videogames and transparently hateful videogames situated? How many white, male playable characters and tokenized female or minority NPCs does a game need before we declare that the whole enterprise is rotten? These questions come up with alarming frequency when examining videogames, yet for all the tropes and slights—or, to use a mot juste, microaggressions—the line separating "problematic" games and hateful games is usually seen as incredibly difficult to cross. It's never been easier to create a stupidly offensive game, yet it's not getting that much easier to declare the whole edifice rotten to its core.

The best thing I can say about Myfarog—the only positive I can say, if you're keeping score at home—is that it doesn't beat around the bush when it comes to its hatefulness. This game is not a collection of digs and slights, its whole existence is one massive act of aggression. It is loathsome, but at least it won't make you work hard to figure out how loathsome it is. Myfarog is the creation of Norwegian black metal musician Varg Vikernes, who spent fifteen years in jail for burning down churches and murdering Norwegian black metal guitarist Euronymous. More relevant to the story of Myfarog: Vikernes is a white supremacist.

Myfarog can be understood as an extension of this worldview. Jeff Treppel has an excellent review of Vikernes's RPG at Metal Sucks that contextualizes the game in terms of both Vikernes's views and debates over the evolution of the RPG genre. You should read the whole thing. For our purposes, however, a few salient points stand out. Myfarog's protagonist, Treppel points out, can only be a white male of Scandinavian descent. Which is not to say that all protagonists are created equal. Indeed, Treppel notes:

The lighter the hair and the fairer the skin, the more blessed by the gods your character is. And, of course, the higher born the better. Nobles are naturally superior to the peasantry in this world. It’s the natural order of things. In fact, it’s even historically accurate (according to Varg).

This bullshit approach to race and gender also permeates Myfarog's treatment of other characters. Women, for instance, are empowered to varying degrees, all of which are lesser than men. As for any character who isn't white—well, let's let Treppel handle this:

Don’t worry, though. People of Middle Eastern and African descent are represented. They are the “filthy”, “vulgar”, “poorly educated”, “animalistic” Koparmenn (“Copper Men”). You can’t play them; they are intended to be cannon fodder. There are two varieties of Copper Men: the Skrælingr (“Weaklings”) and the Myrklingr (“Darklings”). I’m pretty sure that the Weaklings are supposed to be Semitic people, as they receive a bonus to trickery. The Darklings, meanwhile, receive a bonus to spear throwing. You can guess who they’re supposed to represent.

So Myfarog is awful. As Treppel notes, "one of the suggested quest ideas is literally ethnic cleansing." The game is the worst in a way that doesn't require much thought. It is self-evidently awful (and if you don't hold neo-Nazism as self-evidently awful, I really don't know what I can do for you).

a manifesto rendered in the form of a game

But what if we take a moment to think about the specific ways in which Myfarog is awful, if only because most games force us to go through those motions. This is, on the one hand, not the only game to feature problematic characterizations and disparities in power that can loosely be sorted along gender or racial lines. Yet Vikernes is clearly going for more than the casually discriminatory tone of other games; he's aiming to make a real political point.

Myfarog requires the public to consider authorial intent. Whereas many games are open for interpretation—and indeed benefit from the audience's acknowledgment that their developers' ideas aren't always canonical facts—Myfarog is inescapably a product of its creator's worldview. It is a memoir/manifesto rendered in the form of a game. It is a book that describes a game, but really it is just a book—a stupid, hateful book. Were it not for the fact that Vikernes is a white supremacist, this would make it an interesting text, a game that is unusually amenable to all manner of literary analysis techniques. But Vikernes is so disinterested in subtlety, so vile in his outlook, that such analysis is basically unnecessary. Myfarog is what its creator wanted it to be: the rare game that is unambiguously hateful.

Header image from Burzum.org.

Sci-fi horror game SOMA's newest trailer will leave you feeling alone and afraid

Sci-fi survival horror game SOMA wants to mess with your head in every way imaginable. Set in a remote underwater research facility doing some wacky shit with robots and artificial intelligence, the player must survive the aftermath of its collapse into chaos. While recalling visuals from BioShock's Rapture—the gold standard in underwater disaster settings for videogames—the tone of SOMA appears more subdued. Underlying every horrifyingly dark corner in this research facility is the distinct impression that you are not wholly in control of your own mind. Some heavy hints from development team Frictional Games (creators of Amnesia: The Dark Descent) indicate that SOMA will explore the brain-in-a-jar thought experiment, which questions the reliability of your own perception and sense of self. Which is not to mention the fact that the robots in this facility have started thinking of themselves as human.

a story of subtlety and subversion

While the latest trailer doesn't explicitly explore these themes, they're still implied. Showing off the game's cold, bleak, isolated environments, the visuals are overlayed with a juxtaposing voice over remembering happier times from above the surface. An unnamed female character describes her greatest moment of peace as a child watching over the hustle and bustle of a city: "Street food vendors filled the air with aromas of all my favorite foods. The streets below were shattered by the tall buildings. The people pushing through the crowd flowed like paint from an artist's brush. I felt the warm wind in my hair," she says, over the image of a lone searchlight penetrating a dark, lifeless abyss. "For a brief moment I felt connected to the world in a way I never had before. It was the most profound feeling of comfort and sense of belonging I could ever hope for."

All the previews of SOMA promise a story of subtlety and subversion, and this trailer is no different. On their blog, Frictional Games claims that "SOMA is easily the most story-heavy game we have made so far." While the horror of Amnesia relied on the more immediate scares of a haunted house, "SOMA is laid out a bit differently. At first it relies more on a mysterious and creepy tone, slowly ramps up the scariness, and peaks pretty late in the game." Amnesia brought a new perspective on an old horror trope, but "SOMA, on the other hand, derives much of its horror from the subject matter. The real terror will not just come from hard-wired gut reactions, but from thinking about your situation and the events that unfold from it."

If the trailer is any indication, players are in for a treat of interactive storytelling that mimics the slow burn of films like Ex Machina.

Check out Frictional Games' devblog for more of their thoughts. You'll be able to play SOMA on PC and PS4 September 22nd.

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers