Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 220

September 28, 2015

What is love in Lovers in a Dangerous Spacetime?

Running a wacky Rube Goldberg machine fueled by the power of love.

Gods Will Be Watching team parodies what they're good at: videogame violence

Violence is commonplace in videogames. It’s commonplace in most popular media, but its role in games comes under particularly heavy fire. What strikes me as weird about videogame violence, as someone who plays plenty of violent videogames herself, isn’t its prevalence as much as its weightlessness. Violence in games is often trivial, reduced into menial tasks that rarely reflect anything important about characters or plot beyond serving as shallow narrative impetus.

These acts usually result in some form of currency for the player, like coins, money, items, or points, that make them worthwhile—something to be rewarded for. That isn’t to say games haven’t found a way to make these tasks mechanically enjoyable, but that doesn’t make the casual treatment of violence any less unusual for the medium.

"violence implies deeper things than just hitting and killing things"

Some game developers do know a thing or two about the weight of violence, though—Deconstructeam is one of them. Their 2014 point-and-click adventure, Gods Will Be Watching, made players feel the full burden of loss with every difficult choice. Violence was no laughing matter.

So with their most recent jam game, made for Ludum Dare’s “You are the Monster” theme, Deconstructeam jumped on the chance to parody videogame violence, taking a much more nudge-wink approach this time. It’s called Fear Syndicate Thesis and you can download it for free on the Ludum Dare website.

Fear Syndicate Thesis is set in an ambiguously post-apocalyptic world full of hordes of people just standing around to be killed, either beaten by your bat or run over with your motorcycle. The setting seems to be a joke in itself—most games attempt to justify their excessive violence with scenarios that could reasonably allow for mass slaughter to occur. That’s why zombies are so popular.

After spending some time running over people outside the first town and collecting the arbitrary coins they drop (because don’t lie, you probably did—it’s what games expect from us), you proceed to a toll booth where a masked man named Leroux wants to give you a job. But first you have to complete some tasks: kill this number of people with your bat, run over this many people with your bike, collect this many coins from dead bodies. You could say it gets weird from there: the game begins to warp, characters stretch out into distorted pools of pixels, the screen rotates, bright colors flash. But how is this any weirder than what you’re being asked to do in the first place?

The message here isn’t new or mindblowing—its creator refers to the game as “bad” in a postmortem—but I appreciate its unexpected tonal shift. Plus, the backstory explaining it is interesting. According to Deconstructeam, the game was originally meant to be a longer adventure involving post-apocalyptic debt collectors that, based on its description, seemed to glorify the fun of videogame violence rather than critique it. With the clock quickly ticking down though, Deconstructeam turned it all around to create the commentative experience it is now.

“In less than 6 hours, I mixed all the assets mindlessly in an attempt to create pointless entertainment around violence just to lead the player to the reflexion that violence implies deeper things than just hitting and killing things,” writes Deconstructeam. “I wanted to share what I experienced developing the empty fun behind violence without opposition.”

Fear Syndicate Thesis might not be anything genius, but I wouldn't be opposed to its creators expanding on it. If I've learned anything about Deconstructeam from their jam games, it's that they come up with the best titles. A name that cool shouldn’t go to waste.

Download Fear Syndicate Thesis for free on the Ludum Dare website.

The disappointing conventions of Mad Max

Avalanche Studios fails to capture the spirit of George Miller’s films

September 25, 2015

Stop what you're doing and gawp at these perplexing architectural collages

What’s the difference between art and architecture? Here’s Archdaily’s Vanessa Quirk with a run of the mill definition:

Art is a form of self-expression with absolutely no responsibility to anyone or anything. Architecture can be a piece of art, but it must be responsible to people and its context.

What, then, does one make of Matthias Jung’s architectural collages? The German designer cuts up architectural features and pieces them together against ethereal backgrounds in order to create otherworldly designs. Jung’s end results—collections of doors, arches, and windows with some bricks to fill the gaps—are definitely not livable, but that won’t stop you from wishing that they were. To live in one of these collages would be like living in an IRL mash-up of Monument Valley, Brick Blocks, and Wes Anderson’s The Grand Budapest Hotel, which is to say it would be neat but rather precious.

Jung’s collages are probably not what Quirk would describe as architecture—buildings that float in midair are definitionally not responsible to either their natural contexts nor humans. Yet it’s hard not to sense that Jung’s compositions, improbable though they might be, are going for more than mere artistic composition. The pieces of the collage work together as buildings, not livable buildings, but buildings nonetheless. The doors and windows relate to one another. They are not just there to amuse you; the buildings retain a sense of proportion.

Plenty of architecture is wholly irresponsible to people and context. The City of London’s Carbuncle Cup-winning Walkie Talkie might as well have been named “Fuck context and look at all my money!” (Its official name is 20 Fenchurch Street) Architects are also not famous for their sensitivity to humans. Frank Lloyd Wright famously nailed much of the furniture in his houses to the ground, lest occupants rearrange items to suit their needs. So much for humans. Architecture ought perhaps aspire to be respectful of people and context, but it isn’t all the time. Insofar as that is the case, Matthias Jung deserves credit for his architectural experimentation. You couldn’t live in these houses, but there is inherent value in inspiration.

Time Magazine might not get virtual reality, but The New Yorker does

Your brain on anxiety: an interactive explanation with Nicky Case

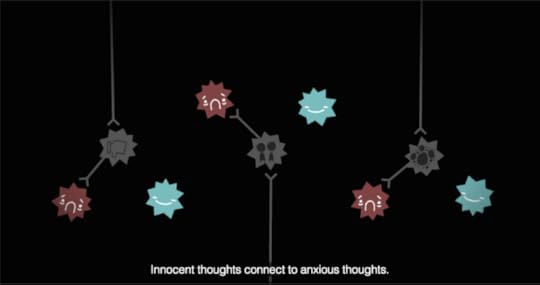

Last year, Nicky Case and Vi Hart released Parables of Polygons, an experiment inspired by Bret Victor's work on Explorable Explanations. Their aim: to bring the best parts of interactivity to a blogpost that might help explain how systemic biases and prejudices can take shape. After being a finalist for the Games for Change award in the Most Innovative category it seemed their playable post had achieved even more than what it set out to do. Putting a new and innovative format on the map, Nicky Case is back once again with Neurotic Neurons, an interactive exploration of the science behind anxiety and its potential therapies.

KS: Do you think knowledge can help fight anxiety or other mental health issues?

Well — a little knowledge is a dangerous thing. One of my biggest pet peeves with popular science articles on psychology is that they all seem to imply your mind is fixed, and it’s genetically determined from birth. Like, “Oh some people are [some Myers-Brigg trait] because of [some gene sequence]” or “Oh women are [gender stereotype] because [misinterpretation of evolutionary psychology].”

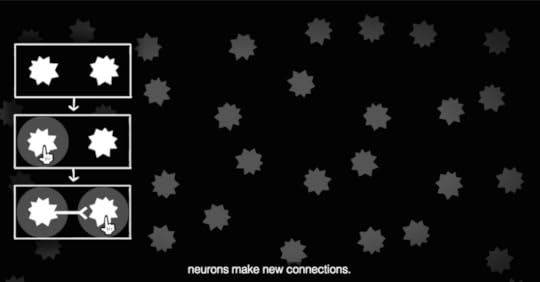

If you have anxiety, or some other mental health issue, and you get the impression that the brain is fixed, not only is that actively harmful, it’s actually false. The most interesting research in neuroscience/psychology surprises us again and again with how malleable the mind is—for better or worse.

To know you can change your brain

So, the kind of knowledge I hoped to spread with Neurons, is the growth/learning mindset, as opposed to the fixed mindset. To know you can change your brain — it’s hard, but not impossible. And I convey this not just through words, but by having the player actually modify a model of a brain. And if you can do it in a simulation, maybe that’s a first small step to doing it in real life.

The growth mindset doesn't only help with overcoming lots of mental issues. It’s a necessary step in many different types of therapies (in psych jargon, we call it “self-efficacy”, or, “internal locus of control”).

KS: It's been a year since the release of Parables of Polygons, and now you've experimented with something like Neurotic Neurons. How has the response to your explorable explanations been?

I’m not sure how many other creators have that “oh god I haven’t made anything substantial since X” guilt, but that has been me for several months now. So, yes, I am relieved to finally be releasing a new interactive thing.

As for explorable explanations, it’s really taken off! That is, of course, a completely biased opinion, but one that may coincidentally happen to be true. Carnegie Mellon University did a hackathon a few months ago focused specifically on explorable explanations! Also, I’m seeing more and more news sites having dedicated teams for making “interactives”. (e.g. FiveThirtyEight, and NYTimes' The Upshot). I am surprised that explorable explanations has been having far more success in journalism than education.

Then again, I guess the newsroom moves much faster than the classroom.

KS: What do you like about these explorable explanations? How do they compare to the kind of work you can do in games?

Having started out in videogames, (I’d say I’m currently on the fuzzy edge of “games”) I really enjoy the freedom Explorable Explanations gives me — I can borrow the best bits of videogames, (learning-by-doing, emergent behavior design) but avoid the expectations and conventions of the medium (scores, fail states, a scruffy middle-age protagonist).

KS: Neurons makes a convincing case for exposure therapy. Have you done some yourself?

The last and only time I’ve been to an actual psychologist was after I came out as queer. My parents had sent me to a child psychologist to convince me I wasn’t queer. (Fortunately, the psychologist was actually understanding, and very helpful. He had lots of cases like mine, where parents try to get him to convince their kids they weren’t queer.)

Since then, I haven’t had any formal therapy sessions, nor do I think I could financially afford to, to be honest. But I can think of a few instances in my life where I overcame deep fears through unintentional exposure.

For example, I used to be really nervous about talking to people, let alone public speaking. But during my internship at some videogames company, I had to constantly request help from supervisors, and give a presentation at the end of every week. At first, of course, I was nervous as hell. I recall standing behind my supervisor for 15 minutes, needing help, but too scared to tap his shoulder, so I just hovered behind him hoping I’d somehow get in his peripheral attention. Eventually, through constant exposure, my social anxiety diminished. And now, I even enjoy public speaking!

"I’m so sorry for bleeding in your sink."

There’s a variant of exposure therapy called “flooding”, where instead of slow, systematic desensitization to a fear, you do it all at once. I have a particularly dramatic story where I overcame an anxiety, through unintentional flooding. When I started living by myself, (shortly after coming out to my parents) I was insecure about whether I could actually take care of myself. I didn’t want to show weakness to my housemates.

So, uh, when I sliced my thumb open in a Safeway, and started bleeding profusely in the aisle, I didn’t call anyone up. I just wrapped it up in a paper towel, took an hour-long commute home, and tried to convince my very concerned housemates I was fine. After trying to wash it out in the sink for ten minutes — while it was full of blood — I finally, finally yelled out for help. The housemate “captain” came in, and I recall specifically the first words out of my mouth: "I’m so sorry for bleeding in your sink."

Anyway, and that’s how, through unintentional flooding therapy, I got over my fear of being vulnerable and asking for help. Now I have a scar on my left thumb as a permanent reminder of that incident, a reminder of “Hey, Nicky, don’t be a dumbass. Ask for help."

KS: What do you hope people walk away from Neurons with? What are you afraid people might misunderstand?

Like I said before, I hope people come away knowing— contrary to so many bad popular science articles—that their brain is not fixed in its ways. You can retrain your brain. It may be hard, it may require assistance, but it is always possible.

Now, the model does have a lot of simplifications. I think this is a good thing—a street map is useful because it simplifies what the city looks like, and this model is useful because I threw away irrelevant details. Still, I’m going to write and publish a list of simplifications I made, and admit gaps in my knowledge. Given that neuroscience/psychology is so full misconceptions like that stupid “we only use 10% of our brain” trope. It’s probably worth clarifying some stuff, and debunking myths.

But, for a rough summary of simplifications I made, try this list:

Thoughts don’t live in individual neurons (duh)

A neuron doesn’t directly cause the next neuron to fire, it raises/lowers its action potential, merely making the next neuron more or less likely to fire

Hebbian & Anti-Hebbian Learning is a pretty good model, has a biological basis in spike-timing-dependent plasticity, and explains a lot about conditioning... except the Zero-Contingency Procedure. Which, I’m going to be honest, is where my knowledge of neuroscience ends. And that’s okay! I can learn. I will learn. Because growth mindset motherfuckeeeeerrrrrrrrr!

Touched by a headshot

Destiny isn’t perfect, but its headshots might be.

Ghosts of Memories sets its puzzles across beautiful, impossible structures

Ghosts of Memories is an upcoming iOS and Android game set in a mystical, isometric world of impossible architecture. While the game it resembles most, Monument Valley, presented its puzzles as compact structures to be rotated, explored, and manipulated, Ghost of Memories spreads its puzzles out across wider, more fragmented areas composed of floating ruins, hanging platforms, and ancient shrines.

Its worlds vary from desolate sand gardens occupied by energy-filled obelisks to volcanic grey islands surrounded by a sea of patterned turquoise, each putting to use Escher-inspired perspective tricks in their own way.

According to the Ghosts of Memories website, you’ll be navigating each world with the help of a special scepter that lets you cross into other dimensions, so while the levels may look neat and unambiguous, there’s more to them than meets the eye.

Learn more about Ghosts of Memories on its website.

The Abject Emptiness of ���Everything���

Why the words "open world" are meaningless.

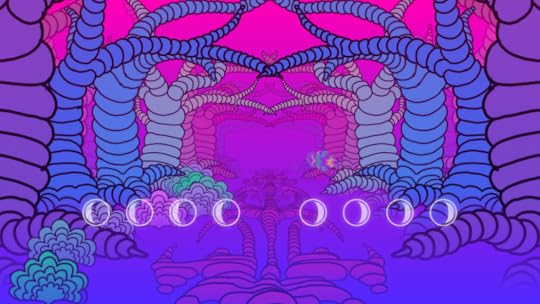

You can play this psychedelic forest game with a moss controller

If nature was able to make a videogame I think it would be Alea. And it's not just because it's a twee, musical hike through a "psychedelic forest." Nor is it due to its two graphics options: "Shrub" and "Tree." I say that because you can play it with a moss controller. Like, actual moss, those green clumps of shrub that grow in the cracks of pavements or atop roofs. You've seen it. Yeah, that stuff.

This is really happening. Right now, at Fantastic Arcade, Alea is being played on an arcade cabinet. You have to poke all four fingers on each hand through two of the springy, soft lichens to get at the buttons underneath. You dip into nature first before connecting to the electronic media beneath. What a bizarre and delightful way to play a game. (I bet that moss will get warm, though.) The idea was net artist Cale Bradbury's, who was inspired by the insectoid typewriters in David Cronenberg's Naked Lunch.

The presence of this moss comes across to me as almost the videogame equivalent of arcology. It's as if the creators want us to consider our relationship with nature when playing around with the game. And that makes sense, especially upon knowing that it's the latest project by Paloma Dawkins, who has already shared with us her rambunctious view of nature in Gardenarium this year.

But specifically, in Alea the challenge is to press buttons to match the rhythm of the music, and it's your success that causes the forest around you to spring up in dance. Light violet and green clovers do a Mexican Wave at your feet and giant curled stems shimmer above your head to your commands. You progress from green shoots to wizened trees as if you're putting the energy into these plants through your performance. And so it playfully draws attention to your connection with nature inside the game as well as outside of it (if you're playing with the moss controller) and the importance of being in tune with it.

"I've been thinking a lot about the moon"

But it's also a little more than that. On its Fantastic Arcade page, Alea is described as an "experience of infinity, and a reminder of the endless light and dark currently occurring in all directions, at all times." This idea of light and dark references the eight buttons that you press in the game as they correspond to moons on-screen. Important to note is that the controls are symmetrical so you only have to keep an eye on four moons at once, making sure to press two buttons at the same time. Each of the moons' default lunar phase on-screen is a new moon; so it's not visible, a blank circle. You know not to press the buttons when you see this. But the moons will regularly fill up in tandem with the music. When a full moon does arrive you have to press the button it represents to successfully match the beat. And your accuracy is shown in a percentage score once the song is over.

Dawkins explained where her mind is when coming up with this unusual control scheme: "I've been thinking a lot about the moon as being a reflection of the sun's light, so the moon is kind of this thing that is reflecting light back on to us and it controls tides and it means so much to balance and nature," she said. "You are kind of this entity controlling these symmetrical moons and therefore controlling the space, but something else is controlling the rhythm."

The effect this has is to place us among nature's cycle and its spaces. In part it reflects our power over it as we command the plants with our button presses—they seem to rely on us. But we, as players, are tied to the whim of the music, and so we don't have full control. This seems to acknowledge that we can never truly escape from the wild no matter how we may try to tame it (we're starting to see this with the world's abandoned villages, such as the vine-covered Houtouwan on China's Shengshan Island). And if that's the case then, as with arcology, we should surely attempt to work with nature rather than against it for the best result.

You can purchase Alea as part of the Humble Bundle Weekly. It's also looking for votes on Steam Greenlight.

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers