Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 213

October 9, 2015

How do cats see the world? This bewildering psychoscape has a rough idea

This cat is out of place. But maybe all cats are out of place. The one in Psychic Cat is probably no more suited to its environment than, say, my cat Smudge who fell through the roof of the greenhouse last year. The temptation was to call Smudge a klutz at the time (and let's be fair, Smudge, you are an absolute dingbat at times). But it's not his fault. We humans invented glass and the concept of a greenhouse. Imagine how strange glass is to a cat. Some hard invisible material that seems to trick light. Think of the puzzling terror they must overcome in that introductory moment when everything in their genetic code draws a blank and their inner alarm bells start ringing.

a vast wasteland with shimmering black lakes

The point is that the synthetic world we build on top of the natural one must seem incredibly alien to a cat. It's no wonder they're so apprehensive when having a new plastic product that was made for them shoved in their face. Too right they're going to give it a sniff and scan your face for any evidence of deception before biting into it. Do you blame them? I'd hunch up like an accordion and give it a frightened lick as well.

The "blasted psychosphere" in Psychic Cat doesn't seem so far-fetched in consideration given that it throws you into a cat's perspective of the world. The cat you control clumsily collides face-first into the jagged rises and falls of the ground as it runs in otherwise elegant animation. And it has to run as there are no trees to climb, no boxes to curl up in; just a vast wasteland with shimmering black lakes and rugged terrain that seems to stretch on forever. Have you ever seen a cat running across open ground? It's a rare sight. They usually pop in-and-out of cover, darting across roads, between bushes. A cat can't survive in this much open space. It is enormously vulnerable.

You feel this before you even meet "The Strange Ones." They appear alongside bizarre electronic squeals from the soundtrack, humanoid and glowing toxic green. They tower over the cat ready to stomp it out of existence. I had a cat that got thrown into a sack and kicked while inside once. It sat at the front door in the early hours of the morning crying and wounded until we woke up. Humans are shit sometimes. And these Strange Ones seem to embody that.

Now we have a bewildering open world and everything sentient inside it turning hostile upon catching sight of your feline form. As the game's description reads, this "cat is in trouble," but the how and why isn't expanded upon beyond that. This is probably due to Psychic Cat not necessarily going for the 'wow, cats must have it hard' angle. This is clearly not a simulator. In fact, it seems to be concerned with nothing else except exploration of its all-black, quasi-phosphorescent landscape. The cat may simply be an icon for our own curiosity.

frazzled electronics conducting a lightning storm

Move the camera around to see beyond the cat's gaze and you'll see a luminescent purple-red fractal smeared across the sky. It's beautifully unexpected and stands out as much as the other rare landmarks to be found. The Strange Ones gather around gigantic spacesuits projected as a hologram or frozen into transparent rock where they kneel in prayer and pose as if in admiration. Weird creatures. Burnt out wrecks of spaceships implying a scientific failure also attract their lurching forms. One of these derelict ships is so huge as to have its own weather system; specifically, its frazzled electronics conducting a lightning storm high above the reach of the cat's agile jump. You can walk into tears of bright neon as if passing through a Star Gate in 2001: A Space Odyssey. Except escape isn't that easy.

With nothing being explained in this place and it being consequently abstruse it may take a while for you to realize the true implication of the game's title. Psychic Cat doesn't refer to its potentially 'psychedelic' visuals. The cat you play as is actually psychic. Well. it has the power of telekinesis, at least, able to pick up and move cubes with its mind. You can even send them barreling into The Strange Ones to have their ragdoll figures start twitching in harmless displays of agonized submission.

You can download Psychic Cat over on itch.io.

Armikrog and the unfulfilled promise of claymation videogames

There’s something uniquely pleasing about claymation videogames, but you won’t find it in Armikrog

A nauseating VR trip inside a famous Van Gogh painting

In 1990, on the hundredth anniversary of Vincent van Gogh’s death, the Journal of the American Medical Association posited that the impressionist had suffered from “Ménière’s disease and not epilepsy.” A disorder of the inner ear, Ménière’s disease is known to cause nausea, hearing troubles, tinnitus, and vertigo.

The JAMA’s diagnosis is widely disputed, but Mac Cauley’s VR tribute to Van Gogh, The Night Café, does little to downplay the idea that the artist suffered from vertigo. This may or may not be intentional. As I noted when previewing the interactive experience in May, Cauley set out to transform Van Gogh’s Le Café de nuit into a 3D space. The environment, which Van Gogh modeled on Arles’ Café de la Gare, can now be traversed by anyone in possession of a VR headset.

That’s exactly what I set out to do last Sunday, when the Kaleidoscope VR Film Festival brought The Night Café to Toronto, and the results were mixed. Cauley’s work is undeniably visually compelling. It unspools enough of Van Gogh’s swirls to make spaces navigable, but allows smaller features like rays of light to radiate through the air with all the weight of a heavy fog.

I’d like to believe the vertigo is intentional.

Each frame of The Night Café is a painting in its own right, but good luck navigating from one frame to the next. Cauley uses VR to achieve a hifalutin form of point-and-click. You aim by looking where you want to go and then move in that direction by applying pressure to a trackpad. (Kaleidoscope’s festival uses headsets with built-in trackpads. I can’t speak to how The Night Café works in other configurations.) This system is as straightforward as it is imprecise. It requires the user to move her head with unnatural precision. VR encourages you to take the periphery of your vision as seriously as its centre, but The Night Café’s navigation system requires you to only think about what is straight in front of you. Add to this the fact that you can only move at a constant speed, and much of your time in The Night Café is likely to be spent trapped in corners and crashing into walls.

The Night Café is therefore a nauseating experience, but in the brief moments before vertigo sets in, it is profoundly compelling. Therein lies the appeal of the JAMA’s interpretation of Van Gogh’s medical history. I’d like to believe the vertigo is intentional. I’d like to believe that The Night Café’s navigation is an attempt to get into the artist’s mind as opposed to a reflection of VR’s current shortcomings. I don’t really believe those things, but I cling to that hope because The Night Café deserves recognition. In the brief moments where Cauley’s work does not induce nausea, it extrapolates Van Gogh’s brushstrokes in a manner any lover of art would surely appreciate.

It���s Still a Man���s, Man���s, Man���s World; Or, Who is Nathan Drake?

The Nathan Drake Collection is a tribute to videogaming’s idealized everyman.

October 8, 2015

At last, a virtual art gallery made for bizarre gifs

A building constructed of concrete slabs with a sign reading “Hyper GIF 3D Gallery” awaits you beyond pixelized trees. An open door beckons. Within it, a description of the current show declares “Akihiko Taniguchi, solo show of GIFs.”

keep digital art within a virtual space

This is the entrance to a browser-based 3D art gallery. While the street you begin on consists of detailed high-rise buildings—across the street is a restaurant, and next to it a brick building appears to have flowers painted on it—the interior of the gallery itself is, much like physical art galleries, comprised of off-white walls, wooden floors, and black labels, leaving color the exclusive domain of the pixel art pieces themselves. A two-dimensional red piece of meat is elevated in the center of a room like a statue. In another room, abstract designs in blues, purples, and greens decorate the wall, like modern art meeting pop art.

A digital gallery of this sort may be the only way to effectively display pieces without putting them on screens in a physical gallery, creating a remove between the art and the viewer, and also without printing the GIFs on paper and fundamentally altering the nature of the work. While past digital art galleries have focused on either migrating traditional art to a digital medium or as venues to preview produce-on-demand physical copies of digital art, Taniguchi’s gallery seeks to keep digital art within a virtual space.

Let the Monument Valley studio help you meditate with this new app

Would you trust ustwo to help you relax and let out all your stress? In a way, if you've played through Monument Valley, you already have. I can't speak for you but I watched my mum play that game through in one session and she was visibly chilled the hell out. I heard her deep sighs of relief and saw her entire posture deflate in that armchair over the duration. I imagine the game had a similar effect upon me.

But PAUSE isn't a game. It's ustwo's latest app and one that apparently combines Tai Chi techniques with proper science to help you meditate when you need it. The idea is to move your fingertip over a pulsating blob of color on the screen of your smartphone. You listen to the gentle ambient sounds (preferably with headphones) and as you trace shapes you should find your focus is drawn inwards, on the here and now.

make "stress relief super simple."

The blob slowly expands the entire time you're touching it. If you lose focus and don't maintain contact the audiovisuals recede in order to lure you back in. Eventually, if you keep at it, that blob will fill the whole screen. At which point you close your eyes, focus on your breathing, and enjoy the soundscape until you're suitably calm.

Doing all this triggers your body's "rest and digest" response. Perhaps that sounds unfeasible. But ustwo claims that the relaxing effect that PAUSE has upon our mind and body has been tested with EEG—brain scanners, basically—and the results prove that it works. It's a collaboration with mental wellness solution company PauseAble after all, who aren't after superficial effects with products like PAUSE, but ones that are supported by science.

Part of the delight of PAUSE is hearing the story of how the idea of it came about. As you can watch in the video above, PauseAble's founder Peng Cheng combined his interest in interactive technology and having to personally overcome depression to make "stress relief super simple." He says he wants other people to find their own inner power to overcome stress by using PAUSE and hopes that it demonstrates "the potential for a new dimension of relationships between technology, design, and human well-being."

The Archer is bringing intertitles to VR, and it works

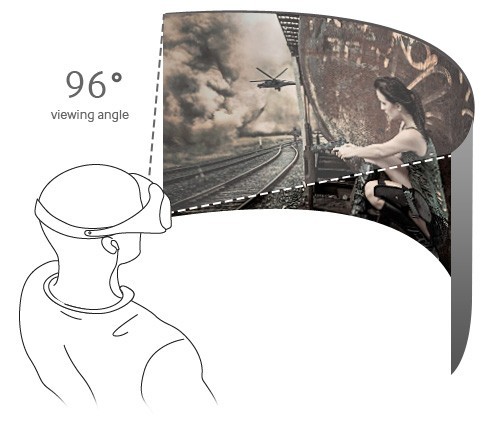

I experienced director Jessica Kantor’s The Archer on Samsung’s Gear VR headset, a $200 piece of kit that, if you believe its manufacturer, “lets you feel the world beyond your peripheral vision.” I did not experience the world beyond my peripheral vision, and was all the happier for it.

Clocking in at a brisk 90 seconds, The Archer reimagines the aesthetic of early silent films for the VR era. It tells the story of a man who visits a female archer for lunch. She goes all William Tell and persuades him to balance an apple on his head that she can use for target practice. I won’t spoil how that works out for the man, but that’s all there is to this story. Move on folks, nothing to see here.

Not that you’d want to see anything else. The Archer takes advantage of VR’s z-depth as an alternative to stereoscopy, but is filmed in black and white. It uses technology as a means to its particular ends and makes no attempt to show off all that the technology can do. To that end, Kantor’s film makes no effort to go far beyond the viewer’s peripheral vision. Its shots are clearly framed and envelope the viewer without requiring constant, speculative head movement.

Down with speculative head movement!

Rather, in order to indicate when the viewer should move her head, The Archer resorts to an old-fashioned cinematic trick: intertitles. As in traditional silent films, Kantor’s intertitles substitute for dialogue. But they also perform an original function, displaying arrows that direct the viewer’s head to the left or right to see the next scene. These gaps and instructions further demarcate segments of the story, establishing a unique rhythm and also ensuring that the head-spinning quality of VR cinema actually has a narrative function.

When they were originally introduced, intertitles compensated for the things film could not do. Film is now a more complete medium—dialogue and colour are the most obvious changes—but The Archer’s intertitles still exists to fill in its blanks. Judging by The Archer’s fellow entries in the Kaleidoscope VR Film Festival, directors have yet to figure out how much you should have to rotate your head when watching a VR film. The technology allows for plenty of horizontal and vertical scanning, but does not always provide clear hints to the viewer. Framing is still useful in VR, but it is harder to pull off when, as Samsung puts it, you can experience the world beyond your peripheral vision. So Kantor, like early silent filmmakers, has provided added hints, a user guide of sorts. Here’s hoping these hints will not always be needed.

In the short term, however, The Archer is a joyful revelation.

Between Us examines the distance and closeness between two city dwellers

This melancholy London—I sometimes imagine that the souls of the lost are compelled to walk through its streets perpetually. One feels them passing like a whiff of air.

- William Butler Yeats

Cloaked in fog and rain, London is a city that invites imagination. Its inhabitants all bundled and bustling, London brings all walks of life together while keeping everyone at a distance.

"I love watching the city as it transforms each evening," says Josh Unsworth, creator of Between Us, a narrative game about two strangers thrown together by chance one such night. "Any city at night has a magical feel, but there's something special about London—it has this incredible energy but also a feeling of subtle otherworldliness and mystery. That's what I hope to capture."

In the recently released playable teaser for Between Us, a woman strikes up conversation with her cabbie. A recent tunnel collapse in the underground had left the city in a standstill, interrupting the daily routine of thousands. A soundtrack by Jess Jones sets the tone for the unusual to take place, her soft and ghostly vocals underscoring an exploratory cello line.

London was seen as more of a haunting ground than a city

To many artists, from Yeats to Thomas Moore, London was seen as more of a haunting ground than a city: everyone doing the same things under a cloak of anonymity, walking past each other, unnoticed, aimless. Unsworth describes the two characters in Between Us as unsure about their place in the world, people who " let their lives drift past them," but come together in a moment where they can finally "break out of their normal existences for one night of truly living." It's a romance, but "between two people and a city rather than each other."

Mimicking the interactions of city life itself, Between Us will revolve around walking, object interaction, and dialogue choices—with each narrative path affecting the tone and context. There's even going to be a texting function, capturing the latest in technology that helps us ignore each other while packed like sardines in a subway car.

Unsworth cites cinema like Night on Earth and Before Sunrise as inspiration for Between Us, and admits that many of the people he's working with are from the world of film rather than videogames. As a game trying to unravel some of the nuances of human connection, he's found one quote from Before Sunrise particularly useful:

I believe if there's any kind of God it wouldn't be in any of us, not you or me but just this little space in between. If there's any kind of magic in this world it must be in the attempt of understanding someone sharing something. I know, it's almost impossible to succeed but who cares really? The answer must be in the attempt.

Unsworth currently plans to release Between Us in the summer of 2016 on Itch.io, Humble and Steam. You can keep track of any updates through the game's Twitter and official website.

The glory days of Net Yaroze as told by the game creators who were there

The challenges and camaraderie of PlayStation's first amateur game-making community.

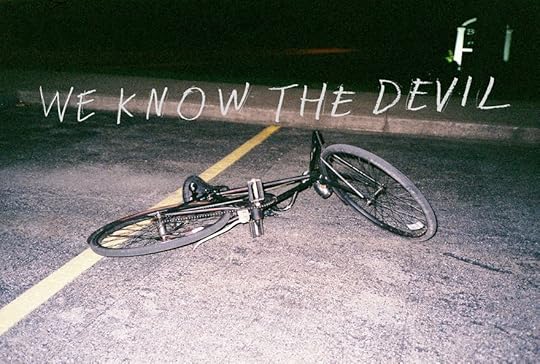

It's Sailor Moon vs. the Devil in this horror story about pre-internet queerdom

Growing up as a queer kid in a rural, religious area can be a challenge. As you’re shuffled from church event to church event, it can be easy to feel stifled, especially if your folks are the evangelical type. Certain types of media can provide a momentary escape from that, such as the bombastic view into another culture that is anime, but in the end, it always seems like you lose a bit of yourself to the darkest part of a society that makes you feel like you have to hide who you really are.

We Know the Devil, a new horror visual novel starring a trio of characters clearly named after Sailor Moon’s Sailor Scouts, aims to express this feeling with a bone-chilling premise. It follows three girls who are doing their best to survive a religious summer camp as they’re forced to spend 12 hours alone in a cabin feeling out their respective queer identities and crushes for one-another while also just shooting the shit about childhood nostalgia like Sailor Moon.

With its strong female role models and explicit gay relationships (in the Japanese version, anyway), Sailor Moon has become a sort of rallying point for many young queer women of the ‘90s, telling them that young girls are capable of taking down even the toughest foes, but even Usagi Tsukino might not be enough to save our protagonists from the threat awaiting them at the end of the night.

“It’s [the game] about being weird and queer and wrong and hoping against hope no one will find out when the actual, literal devil comes for you,” We Know the Devil proclaims on its site. Though the story is designed to service all your potential OTPs (one-true-pairing, internet slang for someone’s preferred relationship amongst a certain group of fictional characters) for the main cast, it also comes with an ominous warning that once the devil arrives, someone’s not making it out fully intact. “Someone will always be left out,” the site says. “The price the two pay will be the third.”

I’m not sure I buy it. Good Sailor Scouts always stick together! Unless all our nostalgic heroes are just lies...

Someone will always be left out

With photo backgrounds taken on actual disposable cameras and an ‘80s style horror synth soundtrack, the game does its best to capture the feeling of being a young girl questioning her identity in the pre-internet era. You can only deal with summer camp bullies and Jesus freaks for so long before even your nostalgia isn’t enough to save you. Can you make it through the night without losing part of your group or yourself? Will you tell your crush how you feel? And will you be able to stay with her when HE arrives?

You can find out for yourself by purchasing We Know the Devil for the cheeky price of $6.66 over on the game's site.

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers