Kill Screen Magazine's Blog, page 203

October 30, 2015

Albino Lullaby exercises jump scares from horror, and not much else

Kooky horror ends up not being very horrifying at all.

Albino Lullaby explores a dead-end for horror games.

October 29, 2015

A play about male clinical depression is now also an interactive story

An Interview is not all black—little pops of colour occasionally surface—but you could be forgiven for thinking that you’ve fallen into a world of blackness.

And so you have. An Interview is Manos Agianniotakis’ interactive adaptation of Bryony Kimmings and Tim Grayburn’s play “Fake It ‘Til You Make It.” The pair’s performances grapple with the issue of clinical depression, particularly as it affects men. Here’s how they describe the show:

Expect home made music, stupid dancing, onstage arguments, real life stories, tears and truths in this wickedly heartwarming and funny celebration of the wonders and pitfalls of the human brain.

Consequently, there are not a million choices for you to make in An Interview. It is an interactive experience that is in large part concerned with feelings of hopelessness. There are things to click, but there is no magic button. An Interview and its source material do not take this lightly. They are not dour for dourness’ sake, but the conversion to interactive fiction has not come with all sorts of game-like features.

An Interview reckons with the gap between personal experiences and general trends. Kimmings and Grayburn note “mental health related suicide is the number one killer of men under 35 in the UK.” Their work—and, by extension, Agianniotakis’—is meant to respond to this phenomenon. The risk here is that the general phenomenon gets conflated with personal experiences. To be depressed is to have a lot in common with others while also often feeling wholly detached from your peers. An Interview addresses this challenge in two ways. First, the interactive narrative allows you to really zoom in the individual experience. You are there, amidst the particulars. You are not inside an infographic. If, however, you find some aspect of yourself in this specific experience, that can help humanize mental health data. “Fake It ‘Til You Make It” moves from the general to the specific; An Interview is moving in the other direction.

You can download An Interview for Windows here, and for Mac here.

Stay, Mum is a tear-jerker about a strained mother-son relationship

According to Freud, one of the most traumatic events in a child's early life can be watching his mother leave. Observing one child who, following his mother's departure, would always joyfully fling his toys far away only to reel them back in and do it all over again, Freud deduced that this "game" was in fact a reenactment of the child's trauma. And by replacing the absence of his mother with that of an object only to recover it immediately allowed the boy to conquer his anguish, Freud theorized. Perhaps this was why this peculiar child never raised a fuss when his mother left. "He made it right with himself, so to speak, by dramatizing the same disappearance and return with the objects he had at hand."

Like much of Freud's analysis, there's not much to back up all the definitive conclusions he extrapolates from this one anecdote, but it does capture something true about human nature. Often, games and play are a child's only recourse for understanding the strange world around them. Whether or not little Timmy was mimicking/conquering his mom's departure through the game he invented for himself, it's clear it served as some sort of coping mechanism.

In iOS narrative puzzle game Stay, Mum, a young boy named John must learn how to cope with his single mother's busy schedule. As she works tirelessly to support them, John is left alone often (to his mother dismay). But, by unleashing his imagination, John discovers he can cure his loneliness with games. Playing with seven different building blocks, he creates all sorts of surreal shapes and imaginary friends to fill his mother's absence. Adorably, every building block John plays with is given to him by his mother, showing how even when she can't be physically with him, she's still giving her son the tools to excel without her.

she's still giving her son the tools to excel without her

Creators Lucid Labs hint that there's a lot more to discover about John's relationship with his mother, and why she's so busy all the time. The soundtrack is both tranquil yet somber, capturing this mother-son duo's longing to just spend more time together. I'm still hoping for a happy ending for little Johnny, though. Because even though the separation may be painful, learning to be okay with absence is an important part of human development. And no matter how lonely he gets, Johnny knows games and play will always be there to keep him company.

Stay, Mum was released today, October 29th, and is available on the iTunes store.

A fascinating look at Museum of Simulation Technology's perspective puzzles

The first time I saw Museum of Simulation Technology was at the Experimental Gameplay Workshop at GDC in 2014.

A forced perspective puzzler about using visual tricks to navigate a labyrinthine dreamworld, it’s one of those charmingly clever games that’s just delightful to watch, especially for a new crowd of people. Each success in the demo prompted some genuine cheers from the audience, and I find myself experiencing that same feeling of fascination watching the game’s latest video from Polygon.

Museum of Simulation Technology seems to combine the child-like wonder and toy-like elements of (the also highly anticipated) SCALE with the reality-bending joy of Perspective and the visual gag-based humor of The Stanley Parable. I still remember the ooh’s and ahh’s of the audience from last year’s demo as creator Albert Shih used forced perspective to turn small objects into large structures he could use to locate each room’s exit: using the Mona Lisa to build a giant ramp, plucking the moon from the sky to find a hidden door, creating a staircase from a deck of cards.

It’s grown a lot since then, as you can see in the new video. While it’s still early alpha, the visual polish is massively improved and there are some new ideas at play. A notable one involves abstract images that, when viewed from the right angle, forms an object that you can pluck from the 2D plane and use just like any other.

Learn more about Museum of Simulation Technology on its website.

What the stage play NieR: Automata is based on tells us about the game

[This article contains spoilers for NieR and Drakengard]

The reveal of NieR: Automata's full title and the first proper story details this week was significant for two reasons: 1) Holy shit, more NieR, and this time it's about machines?!, and 2) We discovered it's based on a Japanese stage play called "YoRHa" that was also penned by the game's writer and director Taro Yoko.

Before getting into this stage play and what it means for NieR: Automata, it's worth remembering the previous work of Yoko as it will be instrumental in understanding where he might be going with NieR: Automata's story.

parallels the survival mentality seen in the tech industries

First off, the man is one of the few directors in videogames who despises the medium's focus on violence and murder. When coming up with his first game as director, Drakengard, back in the early 2000s, he looked at the prevalence of games at the time that glorified killing. He thought you'd have to be "insane" to think that killing should ever be pleasurable. That's why, with Drakengard, he justifies the mass murder committed by the protagonist and his army by depicting them as a "twisted organization where everyone's wrong and unjust." Indeed, Drakengard features a supressed pedophile, a cannibal who eats children, incestual love between two of the main characters, as well as suicide and the discussion of child abuse.

NieR, released in 2010, is a spin-off from the Drakengard series that Yoko has said was influenced by 9/11 and the War on Terror. After these turn-of-the-century events, the vibe that Yoko was getting from society was "you don't have to be insane to kill someone. You just have to think you're right." NieR was a reflection of this thinking. With it, he explored how two opposing perspectives out to kill each other might justify their actions, not necessarily giving preference to either of them.

As such, in NieR you follow a man (called Nier) as he slays beasts known as Shades in order to find a cure for his daughter who has a terminal disease. His reason for killing is to protect his daughter. But by the end of the game you discover that these Shades are actually the spirits of humans who previously separated them from their bodies in order to avoid extinction by the same disease. The idea was to unite the spirits with the clones they had created of their bodies (which were resistant to the disease) once the illness had died out.

Got all that? Okay, good. Now, on a second playthrough of NieR, you gain the ability to hear what the Shades you fight throughout the game are saying. There are also new cutscenes that depict the Shades as people trying to defend their loved ones from Nier's onslaught. Turns out their reason for killing isn't so different to Nier's then, huh? These kinds of revelations is what Yoko's games are all about. It's his way of getting us to engage with discourse around morality, war, and violence in the real world through his work (it's probably not too surprising that he never intended to get involved with videogames in the first place). People often say his games are dark, but Yoko only sees himself as reflecting the world, and seems to suggest that it's the light treatment and expectation of violence in videogames that is truly dark.

"how come I'm not human?"

That's the recap over for now. Try to let all that sink in. Right then, the question that arises with NieR: Automata is what Yoko sees in the world now and how he has let this mold the game's story. What's the discourse he's going to have us thinking about this time? The significance of the stage play that Automata has connections to is that it gives us insight into the answer (huge thanks to Nier2.com's detailed summary of the play). Let's get into it then: "YoRHa," the stage play, is set in the year 11,939AD, which is millennia after NieR took place. But, as with NieR, it's rooted in events that are the consequence of humans nearly going extinct and trying to preserve themselves. This time, the problem is with "Living Machines" that invaded Earth and slaughtered humanity, forcing the survivors to take refuge on the Moon (stick with it).

In hopes of one day resuming life on Earth, the humans constantly send down androids known as YoRHa in order to battle the Living Machines, but after centuries of doing this have so far been unsuccessful. An interesting note is that the Living Machines are able to constantly evolve while humans struggle to keep up continuously developing new technology. It parallels the survival mentality seen in the tech industries in which rapid advances are highly desired and products are made obsolete ever faster. We see this all the time in videogames especially in the pursuit of achieving "realism" through improved computer graphics.

Other themes in the play are more typical of cyberpunk fiction. The play follows the latest group of YoRHa units sent down from the Moon to destroy the machines. On the surface, they end up colliding with older YoRHa units known as The Resistance, who say that these newer models look remarkably human. What all YoRHa units have in common is being programmed with false memories. They're also capable of experience fear of death and sorrow when their friends die. The older units have developed these emotions over time and have even given themselves human names, referring to their group as a "family." Inside, there are parts of them that feel human, but what they lack is the near-human look of the newer units. What ensues is plenty of discussion around what constitutes being human. Does looking human matter? Is having human emotions the ultimate decider on what is human? Is knowing love and fearing death enough to be human?

"I dream, feel emotion… how come I'm not human?" starts one such debate. "Because you're not alive." "Our bodies are made out of mechanical parts." "But, if we break, we will die. I’m so afraid of dying!"

The direct connection to the "YoHRa" stage play that NieR Automata has is that it seems to take place directly after it. You play as the only survivor of the play, one of the newer YoHRa units called No.2 Ver.B, as she is left alone in the world to fight the Living Machines. Where Yoko will take the story from there is anyone's guess. But there is one potential clue in the script of "YoHRa." It goes like this:

Erica: The machines have no emotions, that’s why they have no fear.

No.4: But if the enemy would be as varied as us and could learn, perhaps we might face an enemy with emotions of their own one day.

No.2: That’s for sure…… An enemy like that would be far more dangerous and frightening than what we’re up against now.

Could it be that No.2 ends up discovering new evolved forms of the Living Machines that have developed emotions? It seems a likely direction for Yoko to take the narrative. Especially as it would then touch on themes similar to those explored in the original NieR while also asking the types of questions that Bladerunner, Ghost in the Shell, and Ex Machina did. Where do you draw the line between human and machine? Are you right to kill a machine if it has human emotions and feelings? How humane are human beings if their most invested technology is made to kill?

Of course, while NieR: Automata will probably pry into these profound questions, the only thing certain about it is that it'll be just as violent as Yoko's previous games despite his claims that he is saddened by it. In fact, he said before that he sees how killing permeates videogames, and how there has been no great change to this, as a "personal failure." Yet, by working inside the very thing he despises, Yoko has been driven to call it into question through his narratives, having us reconsider violence in all its forms, inside and outside of videogames.

Die, die, and die again in this Twitter-based adventure game

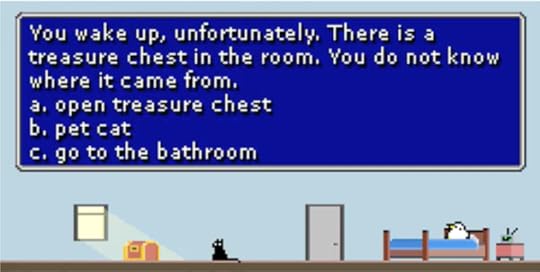

When I scroll through my Twitter feed, I’m never hard-pressed to find selfies, silly jokes, personal anecdotes, opinions on whatever dumb, ignorant thing Donald Trump said recently—but what I don’t expect to find is a Choose Your Own Adventure game, complete with pixel art gifs and a seemingly infinite number of choice-related deaths.

Pixel artist Leon Chang “launched” (or rather “tweeted out”) his social media-based Choose Your Own Adventure game Leon on October 21st. While not the first to make such a game, Chang’s Leon is the first to combine both gifs of original pixel art and hundreds of burnout Twitter accounts, each account linked directly to a choice chosen before it. For example, choose a) to take the elevator, or b) to take the stairs, and a unique path awaits you.

In Leon, I died all sorts of unexpected, silly ways. As an impossibly round pale bird wearing polka-dot pants, said to be Huffin Puffin’ from Yoshi’s Island by Chang himself, I made the incorrect decision to stand up while I peed and toppled over, splitting my head open. Game over. I became rattled with social anxiety on the subway at the sight of cooler animals than my own 8-bit spherical self (Teen Turtles, with capital Ts, to be exact), and while that didn’t kill me, deep down I felt it might. I made the rash decision to fight a monster, only to trip and impale myself with my own sword, which happened to be too heavy for me to carry. Game over, again.

In Leon, I died all sorts of unexpected, silly ways.

With ten or so minutes to spare, anyone can explore all that Chang’s charming Leon has to offer—all its death gags, hints, and 8-bit gifs.

Start Leon Chang’s Leon from the beginning, here.

Sun Dogs uses text to interrogate our solar system

The space-opera scale of Mass Effect, now in text adventure form.

For once, a videogame that has you clear up the violence rather than cause it

Sign up to receive each week's Playlist e-mail here!

Also check out our full, interactive Playlist section.

Viscera Cleanup Detail (PC)

BY Runestorm

For most people, the idea of cleaning up anything sucks. It's a chore; not meant to be enjoyed, just endured. What's going on with Viscera Cleanup Detail then? This is a videogame purely about cleaning that has enjoyed two years of popularity before it was even finished. People are lapping it up like a mop head does spilled liquid. One user review finds comedy in how the person who wrote it refuses to clean their messy room but has scrubbed an entire spaceship in a videogame. Another user review discovers the reason why. "There's something seriously zen about mopping up the aftermath of all these incidents," they write. It's true. Not having to deal with all the smell and feel of the gore, bullet casings, and severed limbs you deal with on the ravaged spaceship, all that's left is the satisfying process of transforming messy rooms into spotless ones. It's bliss.

Perfect for: Janitors, people with ocd, parents of messy teens

Playtime: 10+ Hours

October 28, 2015

Welcome to the terrifying virtual world of nightmare jazz

The intersection of jazz and grotesque virtual people needn't exist. But it does—it's too late to stop it now. The two distant subjects don't meet anywhere else (to my knowledge) except on Swedish jazz student Simon Fransen's YouTube channel. He has brought them together through common interest to a creative place of his own making that he says is "dedicated to jazz where nothing and everything makes sense!"

made to produce music out of pulling their bodies apart

What his "Jam of the Week" series entails is videos of (mostly) classic jazz songs rigidly recreated with sketchy and often sped-up electronic instrumentation and crudely animated computer-made people. Dizzy Gillespie's jazz standard "A Night in Tunisia" becomes "A Nightmare in Tunisia" under Fransen's hand. The song's bass line is re-purposed as the voice of a balding man in a loose shirt-and-jacket combo who head bangs, bops, and seems to otherwise despair on a crop of rocks. As to the song's tune, it appears as the uncanny singing voice of a scowling woman in a suit stood on the same bunch of rocks—she's wholly terrifying.

Many of Fransen's videos are similarly off the fucking wall. If anything connects them it is that he seems to personify his electronically reconfigured jazz songs through his virtual bodies. Not only does part of the music become their voice for the duration of the clip but it also seem to arrest control of their bodies and subject them to a tortuous type of dance. Limbs and necks are stretched, eyeballs smear, heads collapse into torsos as they spin hideously. Again and again, these virtual people gyrate and gesture as if they were puppets to a serial killer's sick invention; an invisible machine made to produce music out of pulling their bodies apart.

I write this especially with "A Nightmare in Tunisia" in mind, as well as his latest video that gradually distorts and rips through The Beatles's "Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds" until only a blue screen of death is left. But there are less nightmarish (and just as baffling) examples of Fransen's videos such as "Princess Jordu" (taking its cues from Clifford Brown and Max Roach's "Jordu") that sees a warrior quarreling with a levitating horse inside a garish Gothic castle.

This isn't the first time we've seen an ongoing project like this. A comparison to Brian's similar melding of electronic music and virtual bodies is warranted. When speaking to Brian earlier this year, he told me that he feels like he is "ripping out all of the emotion that these digital tools could provide" when creating his music. Fransen seems to also want to find emotion in the strained mechanical notes he works with. He turns jazz into dramatic machinima by depicting romances and domestic arguments between lovers.

Why he does this could be questioned eternally. But perhaps this type of unholy spin on 20th century jazz is a gateway to opening it up to generations of people who have grown up with computers and the internet's rapid and bizarre remix culture. "I guess the community for nightmare jazz is still pretty small," Fransman said on Twitter. "I seek to change that." That may explain why Fransman also has tongue-in-cheek educational videos on jazz history on his channel that add a couple of 'wtfs' and 'lols' to the retelling.

h/t The A.V. Club

Kill Screen Magazine's Blog

- Kill Screen Magazine's profile

- 4 followers