Kelly Jensen's Blog, page 118

March 22, 2014

Wrapping Up "About the Girls"

This week's New York Times YA Bestsellers list features one woman.

It's Jane Fonda.

Earlier this week, a piece on The Atlantic asks why it is all girls in the major YA franchises are petite. This isn't the real story though. The real story is what plays out in the comments. Go, read them. Girls having bodies of any type are wrong (they are thin and thus sexual beings or they're fat and useless oafs).

One comment asks where the boys are.

Hank Green made a video about consent last week in light of resent allegations of sexual misconduct within DFTBA and some of their recording artists. The video is problematic, but more problematic are the comments begging him not to get the feminists involved with any sort of project speared by him or his brother because the feminists ruin everything.

Stay away from working with feminist or other overly gender specific interest groups. They tend to screw up your well intention efforts.

I did a quick search on Google a few weeks ago, the same search but swapping the gender. What's not showing up is as powerful as what does show up (read the reblogged comments -- this isn't simply algorithm).

We live in a world where we ask where the boys are, where even in a two-week series devoted entirely to discussing girls, girls reading, and girls in YA fiction, I saw comments and posts that asked about boys or which brought up boys in context of these conversations. Whenever there is a moment for girls to have a space, to have their time in the spotlight, it's rarely celebratory. It's rarely a point of attention for them or their needs or their achievements. It's about what they're taking away from something else.

But talking about girls and girl reading is so, so important.

Just the girls.

The two weeks of posts for our "About the Girls" series have been some of the most thought-provoking and enlightening posts I've read. With no prompting, the posts were in brilliant conversation with one another, and that conversation comes back to one question: why?

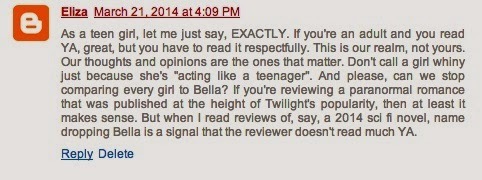

There is much to be said and debated about fiction, especially YA fiction, being "for" any audience, whether "for girls" or "for boys" or "for teens" or not "for teens." But that's not what I want to wrap up this series with. What I want to wrap up the series with is one comment that came up this week that has resonated with me so powerfully. That I think sums up the entire reason we need to keep talking about girls and girls reading and why we not only need to keep talking about this among ourselves as adults, but why we need to actively engage teen readers -- girls and boys and those who may or may not identify as either -- in these discussions, too.

Let me bold the part that stands out to me. The part that is why we must keep talking about why the girls matter.

[P]lease, can we stop comparing every girl to Bella?

Girls are complex, dynamic, and important. They are more than one type and more than being a "not" that type. Why do we limit them?

I think as has become abundantly clear, the reason this needs to keep being brought up is because we knee-jerk any discussion about girls or places where girls have a voice with a "but what about the boys." Yes, care about the boys. Think about them. Help them become their greatest selves. Help them achieve their dreams and goals and push them to be their absolute best, offering everything you can to do it.

Just don't do it at the expense of girls.

Help girls achieve their same dreams, goals, and futures for themselves, and do it without questioning intent, worthiness, or value.

Without asking why.

Boys do not lose anything when girls do well, and girls do not lose anything when they're afforded the same opportunities, respect, and attention their male counterparts are. The contributions of boys and girls, men and women, and those who choose to identify elsewhere on the gender spectrum all matter. This is about what we can achieve when we're open to listening to all voices and when we're open to thinking about the difficulties, the layers, and the nuances that exist in them all.

A huge thank you to everyone who shared a post, either here at Stacked or on your own forum, and a huge thank you to everyone who read, shared, commented, or even thought about this series. I hope you took as much away from it as we have here.

Related StoriesLinks of Note: March 22, 2014Challenging the Expectation of YA Characters as "Role Models" for Girls: Guest Post by Sarah OcklerSome Girls Are Not Okay, and That's Not Fine: Guest Post by Elizabeth Scott

Related StoriesLinks of Note: March 22, 2014Challenging the Expectation of YA Characters as "Role Models" for Girls: Guest Post by Sarah OcklerSome Girls Are Not Okay, and That's Not Fine: Guest Post by Elizabeth Scott

Published on March 22, 2014 22:00

March 21, 2014

Links of Note: March 22, 2014

Pictured above: the displays I did in our teen area for women's history month. Rather than stick to historical novels about females, I thought it'd be more fun to do a display of books featuring great girl characters. When I went back the day after I took this picture, I saw it had been nicely picked at, which makes me so happy.

I promised that I'd do a roundup of links other people had written that fit into the "About the Girls" series, and I'm going to put those in this biweekly roundup. If I missed something, leave a comment and let me know. This is going to be long, so prepare a couple cups of coffee or tea and settle in. First, the general links of note:

There has been some interesting stuff coming out of the UK in relation to gender and marketing, particularly where it comes to books. The Guardian talks about how parents have been pushing back against gendered book marketing, and The Independent decided they will no longer review titles marketed exclusively to one gender. This reminds me of when Jackie pointed out the sexism and gendered approach Scholastic took in one of their series and how Scholastic responded. This is a really thought-provoking post about how Divergent and The Hunger Games avoid real issues of racial and gender violence. Anna has been working on the Everyday Diversity project for a while, which aims to promote diversity in kidlit, particularly in the library. Here's what it is, and here's how (and why) you can get involved. So, the sexual abuse scandal rocking the vlog world? I don't know enough about it to write about it with any sense of authority, but I have read a few things touching on aspects of what's going on that have been thought provoking. First, Carrie Mesrobian touches on why the video Hank Green made about consent is problematic and then Liz Burns talked about power, policies, and ages in regards to this situation and in libraries more broadly. And actually, I lied: I did write a little bit about this on tumblr, mostly giving some more thoughts on what Carrie and Liz had to say. Jeanne wrote a really thought-provoking post about the DFTBA scandal, too. Read this post, read the updated post she links to, and definitely read the comments. Foz Meadows wrote a killer post in response to a New York Times piece about dystopias and YA authors that ran a few weeks back. What's in here about gender is especially fantastic. Curious about raw numbers when it comes to bestselling books? Here's PW's facts and figures for the bestselling 2013 books (which raises a lot of questions in my mind regarding the New York Times Bestsellers list now -- why wasn't Rick Yancey on there longer? Why wasn't Sarah Dessen on there longer?).I know I've shared this before but I'm sharing again because I love this series. Sarah Thompson's still running her fantastic "So you want to read middle grade?" If you're like me and know nothing about middle grade or if you're a huge fan, this series of guest posts are excellent. Speaking of book recommendations, Courtney Summers is doing this new series on her tumblr where her headcrab makes YA recommendations ("What's a headcrab?" is a question answered there, too). She's also giving away a copy of What Goes Around and an advanced copy of Amanda Maciel's Tease, which looks really good. Three books with three tough-to-read-but-all-too-real teen girls. Jennifer Rummel wrote a really excellent post for The Hub this week that traces British women's history through YA fiction. Check it out. Diversity in YA has a book list to 10 diverse YA historicals about girls. I really liked this post and perspective: The Fault in the New York Times Bestsellers List. I often forget what a wonderful resource Pinterest can be for readers. One of the best Pinterest accounts out there, Lee & Low's, is one you have to have on your radar if you're looking for diversity in your collections, in your reading, or in your reader's advisory. This is a goldmine. Matthew Jackson, who has written for us a few times, has an excellent column up at Blastr talking about 21 YA novels that pack a genre punch. This is especially for those readers -- adults -- who are skeptical about how well-written YA fiction can be.

So I'd made a call for people to feel free and write about girls in YA any time during our series and I'd round them up. I am going to miss some posts, so please, alert me to others if I have. And if you're still so compelled to write on this topic, do let me know when you post, too, and I'll try to include it in a future link round up.

Karen over at Teen Librarian Toolbox wrote about the problem of relationships and girls in YA fiction and talks about five of her favorite titles featuring girls. Liz Burns on female friendship in YA fiction, including three books she loved about girl friendships and she asks for input on more (with suggestions in the comments). Ellen Oh talks about the ongoing problem of sexism. Over on her tumblr, Sarah Rees Brennan answers a reader question about female friendships and dives deep into unpacking what friendship portrayals in YA look like and more. I had a teacher in touch with me about how she used two of last week's posts about unlikable female characters to spark a discussion in her classroom as it related to the book they were currently reading. She was even kind enough to share with me the classroom verbatim, and this discussion -- with teenagers -- is so fascinating and exciting and I hope it elicits other similar conversations with teen readers. Cait Spivey wrote this excellent post that asks and expands upon a simple question: "You know YA is about teenagers, right?"Brandy, at Musings of a Bibliophile, talks about the unlikable female characters she loves. Jenny Arch tackles characters, gender, and the age-old likability question. This post by Adrienne Russell is fantastic: I'm not here to make friends. Those last couple of paragraphs in particular are outstanding.

Sarah Andersen is working on something with her students and their reaction/interaction with gender and reading and I cannot wait until she shares more about it. That feels like such a tease of a sentence, but she's been polling her female students about their reading lives and experiences and influences to see what, how, and where gender and what they've been taught may impact them. This should be fascinating.

My posts elsewhere:

I was out of town when last week's Book Fetish ran on Book Riot, but here it is. There's something here for your Harry Potter fans and your fans of making cookies. I rounded up the things I wrote in relation to being on the Printz ballot, including a new guest post at Abby the Librarian about more favorite Printz honor titles, over on my Tumblr.

Related StoriesChallenging the Expectation of YA Characters as "Role Models" for Girls: Guest Post by Sarah OcklerSome Girls Are Not Okay, and That's Not Fine: Guest Post by Elizabeth ScottMore on Girl Friendships in YA Fiction: Guest Post by Morgan Matson

Related StoriesChallenging the Expectation of YA Characters as "Role Models" for Girls: Guest Post by Sarah OcklerSome Girls Are Not Okay, and That's Not Fine: Guest Post by Elizabeth ScottMore on Girl Friendships in YA Fiction: Guest Post by Morgan Matson

Published on March 21, 2014 22:00

March 20, 2014

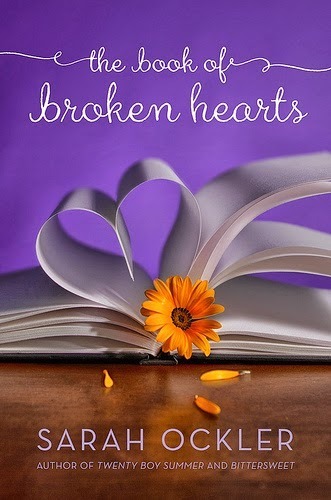

Challenging the Expectation of YA Characters as "Role Models" for Girls: Guest Post by Sarah Ockler

What better way to round out this two-week series on girls in YA than to consider WHY we talk about girls in YA at all. Sarah Ockler is here today talking about why we need to challenge the expectation of characters in YA to be "role models" for girls.

Sarah Ockler is the bestselling author of The Book of Broken Hearts, Bittersweet, Twenty Boy Summer, and Fixing Delilah. Her books have and have received numerous accolades, including ALA's Best Fiction for Young Adults, Girls' Life Top 100 Must Reads, Indie Next List, and nominations for YALSA Teens' Top Ten and NPR's Top 100 Teen Books.

When she's not writing or reading at home in Colorado, Sarah enjoys reading tarot, baking, hugging trees, and road-tripping through the country with her husband, Alex.

Her latest novel, #scandal, hits the shelves in June 2014.

“I hate this book. The character is a terrible role model for teen girls.”

It’s a phrase I’ve encountered again and again, with surprisingly little variation, in discussions of YA literature. Okay, so my research isn’t scientific (unless you consider trolling 1-star reviews of my favorite books while drinking wine and yelling at the screen scientific), but role model reviewing of fictional girls seems to be a rising trend, leveraged as the deciding factor in whether a book gets a positive or a negative rating, a satisfied sigh after the last page or the dreaded “DNF” (did not finish).

Though I believe this kind of criticism generally comes from adult readers with good intentions to encourage, inspire, and nurture young readers, enforcing the expectation that the teen girls of fiction be role models to real teen readers is detrimental to everyone.

When the wine is gone and my eyes burn and Goodreads is overcapacity because I’ve got 75 tabs open and I’m still clicking, I’m left shaking my head, asking one thing:

To the adults who claim to love YA lit . . . why do you hate the teen girls who populate it?

Writing Role Models, AKA Telling Girls What to Do

I don't know any YA writers today who consciously write characters as role models. Much like writing to teach readers a lesson, writing to craft a role model will instantly brand a novel as condescending, preachy, and inauthentic, sinking a book (and possibly a career) before it’s even on the shelves.

That’s not to say authors don’t sometimes (but not always) set out to create strong, vibrant characters, to portray fictional girls who take action, who find strength in adversity, who make decisions and come through their trials with new perspectives. Sometimes (but not always), these characters are admirable and virtuous. Sometimes (but not always), they’re the kinds of characters who might be emulated by others, who might inevitably be called “role models.”

But when that happens in good fiction, it’s in service to the story, to the characters into which writers breathe magic and authentic life, and not to the limiting expectations of adults who believe that YA characters (and by extension, authors) bear the responsibility of showcasing ideal behavior for teen girls.

Novels, first and foremost, are entertaining. An author’s prime directive is to tell a good story. Beyond that, yes, many books are written with the intent (or the unintended outcome) of educating, inspiring, enlightening, disturbing, or challenging us, of fostering discussion, of realistically exploring issues that readers are likely to face, of helping readers feel less alone.

But whether a book is written purely as entertainment or with broader social goals, the expectation that female characters be written as role models for teen girls—and that a book that fails to deliver on that front deserves a thumbs down—is, frankly, utter crap.

She's a Bad Role Model Because REASONS!

For one thing, we can’t even agree on what makes a good teen role model.

Across all categories of YA—contemporary realistic, fantasy, mystery, traditional romance, magic realism, dystopian, and everything in between—the kinds of authors and books that I personally love and admire feature complex, interesting, multilayered female characters. Characters who surprise me, who challenge my expectations, who force me to reconsider my own beliefs, who open my eyes to new ideas and possibilities, who illicit some kind of emotional reaction from me. Characters I’d like to write about. Characters who embody the complex traits I like to discover in girls and women in real life.

Yet, by and large, role model reviewers seem to be Scarlet Lettering these girls—young female characters who are, on the most basic level, just being human. They're exploring their (sometimes unpredictable, often contradictory, usually confusing) emotions. They're confronting new situations and fears, and are often handling them with less grace and aplomb than adults think they should (or, more likely, with less grace and aplomb than we think we would’ve handled things at that age).

The most common citations I’ve seen for bad role model behavior exemplify the double standard that girls and women face every day, and they include traits that run the spectrum from the most rigid traditional gender expectations to the most rigid progressive feminist viewpoints.

We get it coming and going, ladies.

My unscientific online sampling, for example, reveals that a fictional teen girl risks being called a bad role model if:

She feels anger, expresses it, and/or hurts others in the process of that expression. OR She is (or is perceived as) weak or fragile, and does not demonstrably find her "inner strength" by the end of the story.

She says, thinks, or does things that are considered selfish or self-centered. OR She's a doormat for sacrificing or putting some of her own dreams and interests on hold to care for her family, to follow a friend, or to be in a romantic relationship.

She's inconsistent or indecisive, frequently contradicting herself or changing her mind. She doesn’t know what she wants. OR She's too smart for her own good, too assertive in going after what she wants, or too self-aware for a teen girl.

She has "friendship issues" such as ignoring, dismissing, or otherwise disrespecting her seemingly great friends; choosing a crush over her friends; having few or no friends (and being okay with that); or only having male friends. OR She's a “stereotypical cheerleader," a girl who's too perky, too popular, too perfect.

She can't or won't articulate her problems even when friends or adults try to communicate with or help her. OR She's too articulate for a teenager, again, too self aware of her issues.

She’s too sexual: she thinks about, fantasizes about, desires, or engages in sex, masturbation, or other forms of sexual exploration (bonus "bad" points if she does this outside of a committed, monogamous, loving relationship); she enjoys or initiates sex; she’s promiscuous, yet she doesn't feel guilty, become pregnant, or get an STI; she enjoys male attention on her body and/or it makes her feel powerful. OR She's not sexual enough. She’s a prude, a slut-shamer, frumpy, a tomboy, or too sexually naïve for her age.

She gets romantically involved with the "wrong" person, and she doesn't see the obvious signs that this person is controlling, abusive, dangerous, or just plain bad for her; she’s “stupid” for forgiving a romantic partner who is, to the reader, obviously controlling or abusive; OR She’s cruel and dismissive of the pursuer who’s so clearly in love with her (bonus “bad” points if that pursuer is a very sweet, very endearing boy, in which case she’s stupid, selfish, or haughty for not returning his affections).

She smokes, drinks, does drugs, cuts class, curses, or verbally or physically fights with others. OR She's too well-behaved and preachy for a teen girl.

She's emotionally manipulative, either intentionally or unintentionally. OR She's a one-dimensional robot who's not in touch with her emotions.

She's fat, and she eats and enjoys cupcakes without being scolded or feeling guilty, thereby reinforcing unhealthy habits. OR She's fat, and she loses weight for any reason, thereby reinforcing an unhealthy body image and fat shaming.

When faced with a choice about her future, she makes the "wrong" one, such as turning away from a scholarship/college opportunity or dropping her once “ambitious” goals so that she can take some time off, engage in the arts, help a friend or family member, get married, or travel. OR She’s too driven for a girl her age and needs to “live a little” before entering the adult world.

No wonder our heads are spinning.

I’m not suggesting that some of these behaviors aren’t or don’t have the potential to be hugely problematic, or that readers shouldn’t look critically at character behaviors and attitudes, or that we shouldn’t call out abusive, harmful, negative behavior in a story as part of a review or the larger discussion of a book, character, issue, situation, or relationship. I’m also not suggesting that readers force themselves to like, finish, share, or positively review books just to avoid being called judgmental.

The problem I’m seeing in the role model reviews isn’t a simple dislike of a book or character, or a calling out of negative character behavior. It’s the outright dismissal of books (and in some cases, authors) simply because a female character failed to model what the reader considered good, proper behavior for “impressionable” teen readers. She screwed up in ways that teen girls aren’t allowed to (or that we’re not supposed to talk about). Or she didn’t learn from, grow to regret, or ultimately take action to right the wrongs resulting from her screw-ups, regardless of how realistic the portrayal might be. It’s the subtle but crucial difference between “I didn’t like the character or book because the character did XYZ,” versus “This book is bad because the character is a bad role model for teen girls.”

Snakes and Snails and Puppy Dog Tails

Another problem? Role model reviewing reinforces narrow, limiting gender narratives on all sides.

Unsurprisingly, the bad role model stigma does not typically apply to male YA characters. Even when their behavior is criticized (which in itself is rare), it’s often excused by the external situation: boys who face difficult challenges are expected and sometimes even encouraged to act out in ways that girls are never allowed to. This places the responsibility for making “good” choices—and the blame for making “bad” ones—on girls.

When we assign role model expectations to characters, we reinforce limiting gender narratives for all readers, reminding us that while “boys will be boys,” girls must always be good and virtuous—however we’re defining good and virtuous at the moment.

Consider a popular target: Bella Swan. In all the negative reviews about Twilight that cite this protagonist as a terrible role model for girls (and there are a LOT of them), the overarching criticism is that Bella—an awkward teen girl adjusting to a new life with her father, at a new school in a small town, and who’d never been in a serious relationship, and who suddenly became adored and desired by a mysterious, hot boy—should’ve identified Edward’s overprotectiveness and fierce desire for her as controlling, stalking, and abusive. She should’ve rebuked rather than welcomed or sought his advances. Failing that, she should’ve ended the relationship when things got intense. She’s stupid for staying with him. Weak, flighty, vapid, devoid of personality, a follower, a limp noodle, a Mary Sue. Sure, Edward might be the one engaging in controlling behavior, he might be the vampire with all the physical strength and power in the relationship, not to mention money and worldly experience, but Bella’s the one who should’ve “known better” and should’ve done something about it.

She didn’t, though. She stood by her vampire-man, risking almost everything else in her life—including her life and the lives of her friends and family—to be with him. And what does her “stupid” behavior model for her millions of young female readers? Oh, commence the hand-wringing! Let’s ignore what could actually be a really great discussion about love, obsession, power, and desire because we’re too busy wringing all these hands!

One Size Fits, Well, One. Just the One.

Role model reviewing, as I mentioned with the Twilight example, squashes what might’ve had the potential to become a good, important, necessary discussion of an issue or situation, and it does so based on reader judgment of one character’s behavior, in one finite time and place, in one particular story.

The term “role model,” by its very nature, gives me the creeps. It compartmentalizes whole, complex people into roles, and then prescribes a single set of “model” traits, thoughts, behaviors, and values for that role. So, in the “role” of daughter, a girl behaves X. In the “role” of friend, it’s Y. This type of compartmentalization fractures us. It eliminates shades of gray, flat-lining the complexities of human emotion and life by suggesting that in any specific situation or relationship, there is a single, clear choice between right and wrong. That the girl who chooses the right path is good, and the girl who chooses wrong path is bad. That in each of their many compartmentalized roles, good girls inhabit and display the model traits, even when their life situations get complicated, painful, confusing, or deadly.

But how can it ever be that black-and-white?

Sure, Katniss Everdeen (The Hunger Games, by Suzanne Collins)—often cited as a wonderful role model for girls—may be a kickass child soldier who displays virtues of family loyalty, resourcefulness, and compassion in the face of extreme violence, but when it comes to ending a best friendship gone bad, applying for college, confronting a cheating boyfriend, caring for a sick parent, getting off drugs, deciding whether to have sex, or any number of challenges teens face every day, is there a specific Katniss role model behavior to emulate? A simple WWKD prescription? We might be inspired by her strength and cleverness, but would Katniss display the same exact strength and cleverness that she did in her fight-to-the-death Games arena if she had to navigate peer pressure at a party or face an unplanned pregnancy?

Fan fiction aside, we’ll never know, because every person and every situation is different. And to me, as both an author and a reader, those shades of gray and what-ifs are the most fascinating realms to explore.

Bad Girl is as Bad Girl Does

Similarly, if a YA character is less than virtuous, if she treats people poorly or makes “bad” decisions or engages in harmful behavior, is she a bad person? A bad role model? Someone from whom readers can’t or shouldn’t learn? Someone we can’t relate to or root for? Someone in whom we can’t see ourselves? Someone young girls shouldn’t be exposed to? Someone we should all pretend just doesn’t exist in real life?

How is that helpful?

It’s Not The Shape, Nor the Size… It’s How Many Times You Tweet and Meme and Rant About It.

I mentioned that I don’t know any YA authors, myself included, who write with the intention of crafting role models or teaching lessons. Yet I also recognize that, regardless of author intention, readers—teens and adults alike—are likely influenced on some level by characters in books and movies, positively or negatively.

But, I believe that readers are even more heavily influenced by the discussions that happen about those books and movies. Discussions which ultimately translate into messages that we as a society send to young people about what’s good, right, cool, ideal, worthy, and so on.

Considering the power of these often public discussions to ultimately shape societal values, the expectation that fictional characters exemplify good behavior for girls to emulate—and the embracing or dismissal of an entire book based on this type of singular character judgment—is even more problematic, because it sends the message that:

It’s acceptable to judge and dismiss girls who are facing their own challenges, exploring their own emotions, experimenting, learning, testing boundaries, and making what some adults would consider poor choices and mistakes.

Girls don’t have the ability or desire to make their own decisions, regardless of how characters in their favorite books behave. They don’t know the difference between fiction and reality.

Good things will always happen—or bad situations will ultimately be resolved favorably—for girls who make the right choices (which also means, of course, that bad things can and should happen to bad girls).

Readers can’t or shouldn’t relate to, connect with, learn from, or explore with girls who make less than perfect choices or who don’t model the “ideal” female traits in their “roles” as friends, daughters, girlfriends, sisters, students.

Similarly, boys who don’t embrace and display the traditional “masculine” traits of physical strength, power, ambition, expression of anger, virility, and even violence are weak or broken.

Cultural, regional, religious, and other inherent differences among people that may influence their values, behaviors, actions, and beliefs are irrelevant, don’t exist, or aren’t worth exploring.

Hamster Wheels All Around

Essentially, role model reviewing enforces a cycle of perpetual failure:

First, it convinces us that perfection exists.Next, it sets the expectation that girls must achieve this perfection in their behavior, attitudes, looks, values, and thoughts in order to be deemed worthy and acceptable in society.Then, it sends wildly mixed, contradicting, and constantly fluctuating messages about what this perfection means and how to achieve and display it.Finally, when girls inevitably fail (because, hint: there IS no perfection), it reinforces the message that it was their fault, that they didn’t act or think or speak properly. That they’re not good enough.If girls start to recognize the flaws in this scam, many are reluctant to call them out, because confrontation and disobedience may be seen as forms of imperfection. Best just to shut up and get back on the wheel for another go!Lather, rinse, repeat.

This kind of cycle exists in all facets of life, even in adulthood. It doesn’t allow girls and women to experiment and fail in a way that encourages learning, trying again, trying something different, or simply walking away as a legitimate option (ending a toxic friendship, for example, rather than forcing it to “work” simply because girls are expected to cultivate and nurture friendships). It doesn’t permit us to see failures as learning opportunities, as a natural part of growth and making a meaningful life.

It doesn’t allow us to rise from the ashes of our failures—it just keeps handing out matches.

Where Do We Go From Here?

It’s an amazing time to be an author (and reader) of young adult literature. If we’re willing to risk negative reviews and potential censorship, there are actually very few restrictions on the kinds of issues we can explore and on how graphic and descriptive we can be.

We can and do write across a range of scenarios, including lighthearted romantic comedies, reflective coming of age narratives, exciting mysteries, dark fantasies, violent dystopians, gritty realistic portrayals, stories about sex, drugs, homelessness, vampires, zombies, fairies, dancers, scholars, high school, war, abuse, class struggles, death, loss, love, beaches, madcap adventures, driving, working, kissing, and everything in between. And many of these stories aren’t pretty, aren’t perfect. They’re brutal and raw and totally realistic, even when they’re expressed through fantastical creatures and other worlds.

BUT. It's not enough to have the freedom to tell and read these stories if, through the ensuing critical discourse, we’re sending the same stale message: Sure, you can tell stories about “bad” things, but only if the girls in those stories ultimately make good decisions and come out stronger, better, more perfect girls (all dependent, of course, on whose definitions of strong, better, perfect we’re adhering to at the time).

I would love to see us—authors and readers alike—take the expectation of modeling ideal female behavior out of the realm of YA literature entirely, and instead use that literature and its complex, messy, imperfect, good, bad, beautiful female characters to start and continue important discussions, to call out the double standards, to discuss negative behavior and attitudes without condemning the character or the entire book, to embrace diversity and diverse experiences and personalities in our stories even if (especially if) they make us uncomfortable, to encourage girls and women to explore and challenge and question and try and fail and rise up from all those ashes on our own terms.

And, of course, to tell good stories. First and foremost.

***

Sarah Ockler is the author of Twenty Boy Summer, Bittersweet, Fixing Delilah, The Book of Broken Hearts, and the forthcoming #scandal (available in June).

Related StoriesSome Girls Are Not Okay, and That's Not Fine: Guest Post by Elizabeth ScottMore on Girl Friendships in YA Fiction: Guest Post by Morgan MatsonGirls Kicking Ass With Their Brains: Guest Post by Sarah Stevenson

Related StoriesSome Girls Are Not Okay, and That's Not Fine: Guest Post by Elizabeth ScottMore on Girl Friendships in YA Fiction: Guest Post by Morgan MatsonGirls Kicking Ass With Their Brains: Guest Post by Sarah Stevenson

Published on March 20, 2014 22:00

Movie Review: Divergent

Publicity still from SummitI attended an advance screening of Divergent on Tuesday, before a lot of the reviews started to come in. As of the moment I write this, the movie holds a 36% rotten score on Rotten Tomatoes. With 71 reviews counted, it doesn’t seem likely to gain much ground. These numbers surprised me initially, since I thought the movie was pretty solid: beautifully shot, impressive settings (particularly the dystopian Chicago landscapes), and strong acting from Shailene Woodley.

Publicity still from SummitI attended an advance screening of Divergent on Tuesday, before a lot of the reviews started to come in. As of the moment I write this, the movie holds a 36% rotten score on Rotten Tomatoes. With 71 reviews counted, it doesn’t seem likely to gain much ground. These numbers surprised me initially, since I thought the movie was pretty solid: beautifully shot, impressive settings (particularly the dystopian Chicago landscapes), and strong acting from Shailene Woodley. The problem, I think, is that the movie is pretty solid for fans. It’s not going to win over people who didn’t care for the book, and I don’t think it’s going to hit a home run with people coming in blind.

The major issue comes in some of the translation of the political conflicts from the book to the screen. As readers of the book, we know why Erudite wants to slaughter the Abnegation and its leaders. We understand better how the serum that controls the Dauntless works. These explanations are thorough in the book, but perfunctory, almost throwaway, on the screen.

There’s a very brief scene where Four shows Tris some of the serum that is later used on the Dauntless, but it doesn’t explain how the Erudite can control them so completely – Four simply says it makes the Dauntless suggestible. There’s a missing link there.

Similarly, there’s a great deal of foreshadowing that Erudite and Jeanine have something nefarious planned, but it’s never indicated clearly why they want to do so. There’s some discussion of rumors about Abnegation abusing their power, but it’s so nebulous that viewers are left wondering why anyone gives these rumors any credence. And there’s no motivation given for the Dauntless leaders to team up with the Erudite – as viewers, we can speculate, but the only concrete reason given to us is that they’re just colossal jerks.

These gaps are problematic for a number of reasons. Some viewers may think they missed something, but more will assume that there’s simply no explanation given. The end result is that people unfamiliar with the book will write the movie off as silly. The premise (about dividing people into factions based on character traits) already strains credulity, despite its power as a metaphor for teenage life. When character motivations are muddy too, it’s easy to see the entire movie as nonsensical.

I’m writing all of this as a fan (though not a superfan) of the book. I enjoyed the movie quite a lot. It’s stunning to look at. Woodley is a great Tris. The first half is actually quite good, even for people who haven’t read the book. Viewers will understand the initiation process and the physical and psychological tests, which are action-packed and thrilling. The way the fear landscapes are brought to the screen is interesting (albeit slightly different from the book, but in a way that makes sense). There are some genuinely funny moments during the first half as well. It’s the second half that suffers due to the reasons I mentioned earlier.

I was watching in a theater of mostly adults, and they giggled at some moments that weren’t really funny. It was a little irritating to me, but I can see how people would view some of these lines as cheesy. (It’s not just the lines about feelings, either. There’s a couple in the final confrontation with Jeanine that are a bit wince-worthy.)

On a final note, the director or screenwriter or some other person decided to change the fear of intimacy with Four into an attempted rape in Tris' final test in the fear landscape, which boggles my mind. I feel like I could write a whole other post about this thing alone, so I won’t discuss it more here – but it’s definitely discussable. (Non-spoiler: I don't approve.)

Let me know in the comments what you think of the movie when you see it.

Published on March 20, 2014 16:53

March 19, 2014

Some Girls Are Not Okay, and That's Not Fine: Guest Post by Elizabeth Scott

We've talked about "unlikable" ladies in this series a couple of times, but it doesn't hurt to hammer it home another time. Today, Elizabeth Scott talks about writing girls who become unlikable to readers and about who is guilty of labeling girls as such.

Elizabeth Scott grew up in a town so small it didn't even have a post office, thought it did boast an impressive cattle population. She's sold hardware and pantyhose, and had a memorable three day stint in the dot.com industry where she learned she really didn't want a career burning CDs. She's the author of twelve YA novels, the latest of which is Heartbeat. You can find her at elizabethwrites.com or @escottwrites.

I write stories about girls. And a lot of the time, some people get very upset with the way my heroines actor react to what's going on around them.

My girls have been called mean, uncaring, whiny, stupid and that's just a start.

Here's the kicker. Tthe people saying these things? Other girls. Other women.

And yes, of course anyone who reads a book is entitled to their own opinion. If you think a main character in my books is someone you wished would get punched, or is a bitch, or stupid for being angry, then you have every right to think and say that.

I'm just wondering why.

Why is it so bad for a teenage girl to be angry?

In my latest novel, Heartbeat, Emma's pregnant mother dies suddenly, and Emma's stepfather, Dan, chooses to put his dead wife on life support because the baby she's carrying is still alive.

The thing is, he didn't ask Emma what she thought about his choice. And okay, he's an adult, but he's also her family. And it's her mother.

Emma takes what Dan does as a betrayal. Not just of her, but of what she believes her mother was thinking about her atrisk pregnancy.

She doesn't get depressed, at least not by conventional standards. Instead she lashes out. She gets angry. She looks at her stepfather, who has always been her ally since the moment he entered her life, and sees someone who didn't think of her once when her mother died.

She isn't kind to him. I think that's okay, because she's grieving.

But some readers think it isn't, and that makes me wonder

Why do darker emotions like grief or anger provoke such visceral responses? To make reviewers label Emma as thoughtless, selfish, cruel. As a bitch.

If Emma had been male, would her anger make female readers so angry?

I want to think so, but I'm not sure it's true.

I don't want to think female readers of YA are uncomfortable with strong emotions like rage in stories about teenage girls. I don't want to think that women are afraid of women with problems. I'd like to think that it's because it's easy to forget how hard it can be to be a teenage girl who's suffering and who shows it.

I'd like to think that, but I'm not sure it's true.

I know readers come to books with their own experiences and that not every girl can be liked.

But are girls who cheat on their boyfriend or detach from life after surviving a plane crash or who are in the stranglehold of a five year captivity or who lost their best friend with no explanation or who are angry that their mother is dead that bad? Is it so impossible to read stories about girls like this and think that they are something beyond selfish or stupid or cruel?

Is it possible to think they are simply human?

I hope so.

I'd like to think other female readers do too.

***

Elizabeth Scott's most recent release, Heartbeat, is available now.

Related StoriesMore on Girl Friendships in YA Fiction: Guest Post by Morgan MatsonGirls Kicking Ass With Their Brains: Guest Post by Sarah StevensonHow to Relationship -- Guest Post by Corey Ann Haydu

Related StoriesMore on Girl Friendships in YA Fiction: Guest Post by Morgan MatsonGirls Kicking Ass With Their Brains: Guest Post by Sarah StevensonHow to Relationship -- Guest Post by Corey Ann Haydu

Published on March 19, 2014 22:00

March 18, 2014

More on Girl Friendships in YA Fiction: Guest Post by Morgan Matson

Earlier in this series, Jessica Spotswood talked about female friendship in YA fiction. Today, we're going to revisit that topic with a post from Morgan Matson. Let's keep talking about where and how we are and are not seeing positive girl friendships in YA fiction.

Morgan Matson received her MFA in Writing for Children from the New School. She was named a Publishers Weekly Flying Start author for her first book, Amy & Roger’s Epic Detour, which was also recognized as an ALA Top Ten Best Book for Young Adults. Her second book, Second Chance Summer, won the California State Book Award. She lives in Los Angeles.

When I was asked to do this guest post, and given a list of possible topic ideas, the one that I knew I had to write about, without a second thought, was friendship in YA literature. Because of the nature of the books I’ve been writing recently, it’s been on my mind. But it’s been something I’ve been thinking about, on and off, for years.

In the spring of 2012, I was putting the final touches on Second Chance Summer, my second book. The book was pretty much done – which meant it was time to figure out what the next book was going to be.

I had an idea. But I didn’t love it. It was about a girl, and a boy, and a breakup, and a new boy, some family drama, and maybe some stuff with Ibsen and the school’s theater department (this idea never really got very far). But I kept thinking that it felt like I’d already written the book, before I even started it. And a persistent thought kept swirling around in my head – I didn’t just want to write about romance. I wanted to write about friendship.

In my high school experience, it was my friends who were my constant, my tight-knit group of four (and then five, and then six) who were the center of my world. Boys were there, of course – to swoon over and crush on and date and go to the prom with and sob over at two AM. They were there filling the pages of my journal and the subject of hours and hours of phone calls. But when I think back on my high school experience, the boys were the cameos and exciting guest stars, while my friends were the series regulars. Friendship was, in experience, more important to me than romance. So why hadn’t friendship featured more in my books until now?

Why did it seem like friendship was always taking a backseat to romance in YA?

It just seems like, more often than not (and I count myself in this group) authors are much more focused on the romance, and the friend often takes the role the BFF takes in a rom-com – there in the background, to talk to the heroine about her boy problems, and not do much else.

It raised the question for me – is romance simply easier to write? There is a lot of mileage to be gotten out of chemistry between two characters, that initial spark, the obstacles, the feeling that the romance is building to something….whereas friendship usually has much fewer obstacles, a more difficult-to-describe chemistry, and only builds to…a deeper and more meaningful friendship. Is this why friendship loses out to love?

This is not to say that there aren’t absolutely amazing examples of YA girl friendships. With Scarlett and Halley in Someone Like You, Sarah Dessen entered the Book Friendship Hall of Fame. Theirs is a friendship that goes back years, with a rich history that feels real. Even though we’re seeing Halley and Scarlett in high school, you can sense in their interactions their younger selves. It’s not a static, idealized friendship, either. There is deep affection between the girls, but they keep secrets from each other and let each other down and get in fights. It felt like a real friendship, the kind that shows up rarely in books, the kind that makes you want to call your BFF immediately because something in it reminds you of her. When I saw Scarlett make an appearance in This Lullaby (another Dessen knock-it-out-of-the-park friendship book, which I’ll be discussing in a bit) I was as excited to see her as any friend I hadn’t caught up with in a while. And as I got to the end of her scene, I was more disappointed than I realized I would be that we hadn’t gotten any mention of Halley. But I knew we really didn’t need one – of course Scarlett and Halley were fine. They were those kinds of friends.

I also really love the friendship dynamic between Emily and Meg in Siobhan Vivian’s Same Difference. These are girls who have been friends for years, whose friendship is tested the summer that Emily attends an art program, and Meg gets a serious boyfriend. I love this book because it deals with change within a friendship. Although it’s a bumpy journey to get there, Meg and Emily are still friends at the book’s end – and they have learned to stay friends while each allowing the other one to grow and change. I feel like seeing friendships evolve is also rarer than it should be in YA, where friendships can sometimes feel very static.

Jessi Kirby’s Golden also paints a picture of a friendship that I love. Parker and her BFF Kat have a fantastic dynamic – Parker is studious and hardworking, Kat is more daring and willing to take risks. But Kat is also the more realistic of the two, and pushes Parker to succeed, even knowing that this means that Parker will be leaving their small town – and her – behind. It’s never saccharine or overdone, but this book is a great example of what being a truly good friend can sometimes look like.

These are all amazing examples of the one-on-one BFF-dom. I feel like I see this much more in YA than the group of friends. But I’d spent high school with a group of friends, and I knew how much fun – but also how challenging – it could be, to navigate the changing dynamics between people. There are a few books that have done the group of friends so, so well, and the very best example of this is, in my opinion, are the friends in This Lullaby, also by Sarah Dessen. Not only is it one of my all-time favorite books, but there is such a great friend group at the center of it – an established group, with history and tradition and tension and rivalries. Reading this book was the first time I felt like the experience I’d had with my high school friends was truly represented. I would say that Remy’s arc with her friends is just as important – and hard to separate from – her romantic arc with Dexter. And the friends grow and change in this book, and their dynamics within the group change.

I also think that a special shout-out in the friend-group category needs to be given to Ann Brashares and the Sisterhood books. The friendship between these four girls is the focus of the series, and I loved that about it. The boys come and go but the girls are the constant, loyal to each other (sometimes to their detriment) above anyone else.

One thing I noticed, as I started to put together this list, was that all these books contain established friendships. These aren’t new friends being made over the course of the book, but friendships that have history and texture to them, that feel lived-in and real, not something new and shiny.

I have certainly been guilty of reaching for the new and shiny. In both Amy & Roger and Second Chance Summer, the friends the heroine previously had are dispatched with early on so that she can meet new people (or re-meet old friends in the case of SCS). And I notice this phenomenon a lot in YA, with a new friend there (usually along with a new boy) to take the heroine through the story.

Is it harder to write the history of a friendship (or a friend group) than a new and shiny friend, where there is everything to learn? In the same vein, is it harder to write about a relationship than the swoony, falling-in-love of it all?

This brings me back to the love vs. friendship question. I am also very guilty of this in my own writing. My heroines make friends throughout the course of the books, but the real connections they make are with boys. Romance is elevated above friendship, and by writing the books the way that I have, the message, albeit unintentional, is that romance is, in the end, more important than friendship.

There is also a striking lack of platonic girl-boy friendships in YA. There are lots of friendships that turn into romance (again, I’m guilty of this) but fewer girl-boy friendships in which neither party is interested in the other. When I was writing Since You’ve Been Gone, I knew from the beginning that I wanted it to be about friendship – all different kinds. An established best-friendship, a group of friends, girl-guy friends, guy-guy friends, new friends, old friends, friendship between siblings, friendship between parents and teens. (And of course, there’s a romance as well. I mean, I wasn’t going to quit cold turkey.) I’m sure once the book is released, I’ll know how successful this was. But one of the things I’m proudest of in the book is a friendship between a guy and a girl that never turns into anything except a deeper friendship. I think that by always turning friendship into romance in YA, we’re denying a major an important fact of life – it’s possible (and recommended!) to have friends whom you don’t want to kiss.

I feel like I have raised more questions than I’ve answered in this post – but they are questions that I am trying to address, in my own way. My new book series, The Girls of Summer, is about a group of four long-time best friends who come together every summer. There are boys, of course, but friendship will be at the heart – and at the center – of the books.

***

Morgan Matson is the author of Amy & Roger's Epic Detour, Second Chance Summer, and the forthcoming Since You've Been Gone, available in early May.

Related StoriesGirls Kicking Ass With Their Brains: Guest Post by Sarah StevensonHow to Relationship -- Guest Post by Corey Ann HayduPositive Girl Friendships in YA: Guest Post by Jessica Spotswood

Related StoriesGirls Kicking Ass With Their Brains: Guest Post by Sarah StevensonHow to Relationship -- Guest Post by Corey Ann HayduPositive Girl Friendships in YA: Guest Post by Jessica Spotswood

Published on March 18, 2014 21:58

March 17, 2014

Girls Kicking Ass With Their Brains: Guest Post by Sarah Stevenson

Let's talk about girls who kick ass today. But let's not focus entirely on the girls who are kicking ass when it comes to power and physical prowess. Instead, let's hear about the girls who are smart, clever, savvy individuals. Sarah Stevenson will talk about her favorite smart girls who kick ass with their brains -- and bonus, this post is definitely for those seeking to hear more about girls in genre fiction being fiercely intelligent.

Sarah Jamila Stevenson is a writer, artist, graphic designer, introvert, closet geek, good eater, struggling blogger, lapsed piano player, ukulele noodler, household-chore-ignorer and occasional world traveler. Her previous lives include spelling bee nerd, suburban Southern California teenager, Berkeley art student, underappreciated temp, and humor columnist for a video game website. Throughout said lives, she has acquired numerous skills of questionable usefulness, like intaglio printmaking, Welsh language, and an uncanny knack for Mario Tennis. She lives in Northern California with her husband and two cats. She is the author of three YA novels: The Latte Rebellion (2011), Underneath(2013), and The Truth Against the World (forthcoming June 2014). Visit her atwww.SarahJamilaStevenson.com.

I could not be more thrilled that my Kidlitosphere compadre Kelly invited me to participate in Women's History Month over here at STACKED—so the first thing I want to say is thanks for having me! I'm excited to have the opportunity to talk books (obvs. one of my favorite subjects in the universe) and I'm even more excited to talk about girls in YA fiction. I mean, it is an amazing time to be a girl character in YA fiction. We girls rock on the page. We win gladiatorial-style fights to the death. We compete with the boys—and hold our own—at everything from swords to sorcery to straight-out survival. Just ask Katniss Everdeen (The Hunger Games) or Katsa (Graceling), Alanna the Lioness or Jacky "Bloody Jack" Faber: Girls Kick Ass.

As you can see from that list, I really like reading about girls who are strong and accomplished and quick, who use powers both physical and supernatural to survive and thrive. But as an author who (so far, anyway) writes characters who are far more human than superhuman, I'm also a fan of girl characters who use cleverness and intelligence to make their way, whether it's book learnin' or street smarts. It's a running theme in my own books, too. Asha, the narrator of my first book The Latte Rebellion, is bright and academic, but her bright ideas also land her in major hot water. Fortunately, she's clever enough to swim rather than sink. We need realistic, believable girl characters (and guys!) to show us that brainpower is just as important as physical strength, and sometimes more so. So, for women's history month, I present you with my list of Favorite YA Girl Characters Who Kick Ass With Their Brains. (And not just with their ass-kicking boots. Though I would dearly love a pair of those…).

Can I quickly just say—this was SO HARD. There are a lot of amazing, brainy YA characters. I noticed that many of these ladies have multiple books, which probably made them more memorable and likely to stick in my head, since I've gotten to spend time with them over multiple adventures. You may also notice that there are middle grade books on this list, too: I just couldn't bear to leave out some younger female protagonists simply because they're tweens. They are simply too awesome to ignore. So here you go, in no particular order:

1. Jacky Faber

Yes, I already mentioned her above under girls who kick (physical) ass, but honestly? It's Jacky's cleverness that is her true appeal for me. It isn't just that she can hold her own physically, thanks to the School of Hard Knocks, but the fact that she's smart enough to successfully do the crazy things she does, from disguising herself as a ship's boy in the first book to, in some of the more recent Bloody Jack volumes, penning and organizing stage performances and, basically, running her own business. (Even if some of that business is slightly shady, perhaps a bit piratical...)

2. Hattie Brooks

In Hattie Big Sky, Hattie Brooks was driven to prove herself capable and practical, and in the sequel, Hattie Ever After, she's driven to prove herself intellectually capable in a world that is still very much a man's world. A lot of her long-term success—in my mind—comes from learning her limitations, but also learning that those limitations are due to factors beyond her control. There are certain things women can't do during the time period she lives in, but more than that, there are just things that humans can't always do, and sometimes life doesn't work out the way you expect it to. Yet she carries on, and it's her determination and smarts and willingness to work hard that get here where she needs to be, and where she wants to be: on the reporting staff of a newspaper, at a time when being a "woman reporter" was rare.

3. Frankie Landau-Banks

Oh, wow. I can't say much about Frankie without giving away the plot of The Disreputable History of Frankie Landau-Banks, but she is one of my favorite characters for sheer moxie and mischief and the smarts not to get caught. My character Asha would absolutely worship Frankie. And I can't help but love the whole "least likely suspect" scenario, in which the academic girl everyone thinks is probably boring and normal is hiding a whole secret life. Please feel free to assume there is a psychological explanation for this involving wishful thinking and/or vicarious enjoyment because you're probably right.

4. Flora Segunda

Flora! She has to save the world by finding out who she really is—the introspective mystery that involves her in a larger web of intrigue. Definitely the type of plot I gravitate towards, and as a character, she is unique, quirky (okay, downright bizarre at times) but always, always searching and wondering and trying. And it isn't just Flora, but her entire world that lends itself to Girls Kicking Ass. The alternate world she lives in is matriarchal, and women tend to run things, so it's a very strong-female-oriented fantasy setting in Flora Segunda, Flora's Dare, and Flora's Fury. Dare, win, or disappear!

5. Seraphina Dombegh

In the more recent fantasy novel Seraphina by Rachel Hartman, the title character is a musical genius, but she also wields a very formidable and logical intelligence—one which, in her world, is generally associated more with dragons. And dragons are not exactly universally loved for it, in this scenario. Seraphina's unusual dragon-like skills draw the wrong kind of attention, but they also make her a perfect candidate for bringing humans and dragons together for mutual understanding. Of course, she's got to solve a murder mystery first…

6. Meg Murry

How could I have this list without Madeleine L'Engle's beloved Meg Murry, who is practically the original Girl Who Kicks Ass With Her Brain? I mean that almost literally. In A Wrinkle in Time, it's Meg who saves her brother, her family, and saves the human race, too. I was reminded of how much I love Meg when I read the recent graphic novel adaptation of A Wrinkle in Time by Hope Larson—Meg is smart and science-minded, a reader and a thinker, and as a kid reading this, I was transfixed by a heroine who felt so much more "like me," who had adventures even if she wasn't a daredevil, and who was brave and full of heart.

7. Theodosia Throckmorton

For an amazing middle grade heroine, I love Theodosia Throckmorton, star of Robin LaFevers' series by the same name. She's a budding archaeologist and an expert on all things Egyptian—both natural and supernatural. Her knowledge of Egyptology and hieroglyphs is rivaled only by her ability to defuse curses and detect evil magic.

8. Dewey Kerrigan

In The Green Glass Sea and White Sands, Red Menace by Ellen Klages, Dewey's father is a scientist working on the Manhattan Project, out in the New Mexico desert in 1943. Dewey is mechanically-minded, loves numbers and patterns, and isn't as easy with people…but she finds a place in this world of scientists, and her intelligence helps her ultimately figure out not just what her father is working on, but also how to be herself.

9. Gilda Joyce

Another really fun middle grade series is the Gilda Joyce books by Jennifer Allison. Gilda is a Psychic Investigator and gets to solve all sorts of entertaining mysteries. Even better, she gets to spend the summer as an intern at the International Spy Museum, which is a real place and I want to go there.

10. Lindy Sachs

Lindy is the hero of The Short Seller by Elissa Brent Weisman. She's only a seventh grader, but it turns out she has a rather unexpected and major talent for day trading on the stock market. But it's not just talent alone—she makes a point of reading and learning about stocks, and her extracurricular studies start to pay off. Until, of course, havoc ensues.

And there you go! I'm sure I've missed a few and will kick myself in my own ass later for it, but these are definitely some of my absolute favorite brainiac girls in YA fiction. If you haven't read about their adventures, you're missing out.

***

Sarah Jamila Stevenson is the author of The Latte Rebellion, Underneath, and the forthcoming (June) novel The Truth Against the World.

Related StoriesHow to Relationship -- Guest Post by Corey Ann HayduThe Unlikable Female Protagonist: A Field Guide to Identification in the Wild -- Guest Post by Sarah McCarryWhose Feminism(s)?: Guest Post by Kirstin Cronn-Mills

Related StoriesHow to Relationship -- Guest Post by Corey Ann HayduThe Unlikable Female Protagonist: A Field Guide to Identification in the Wild -- Guest Post by Sarah McCarryWhose Feminism(s)?: Guest Post by Kirstin Cronn-Mills

Published on March 17, 2014 22:00

March 16, 2014

How to Relationship -- Guest Post by Corey Ann Haydu

Today's post comes from Corey Ann Haydu, and it's about relationships. What are the common relationship narratives we come to expect in YA fiction? Does everything have to be about teens having sex? Corey digs in and questions our expected -- and unexpected -- beliefs about sexuality in YA fiction, especially as it comes to girls.

Corey Ann Haydu is the author of OCD LOVE STORY and the upcoming novels LIFE BY COMMITTEE and RULES FOR STEALING STARS. She lives in Brooklyn, loves cheese and podcasts, and writes (and eavesdrops) in cafes.

I am an imperfect feminist and an imperfect reader and if we’re all pretty honest these are the only kinds of feminists and readers there are. Because feminism and reading are both explorations and when we explore we mess up.

This is a blog post about trying to be a better feminist and a better reader and a person less motivated by the Relationship Narratives that we’ve been told our whole lives and how YA literature does and does not come into play. This is a post about what we’re telling women about marriage and what we’re telling teenagers about sex, and how literature reinforces an Ideal that maybe doesn’t exist.

This is also a blog post about teen sexuality and our discomfort with it, which, because I am an imperfect feminist and an imperfect reader, sometimes includes my discomfort with it.

A few months back I was part of a reading at a Children’s bookstore. The reading was about relationships in YA literature, and our panel of YA authors each read a flirting or kissing scene from our books.

Then something happened.

Wonderful YA author Mindy Raf read a scene from her recent The Symptoms of My Insanity. It was less than a sex scene. It was more than a kissing scene. It was uncomfortable and funny. It was specific and evocative. It was messy and brilliant. It was too much for the children’s bookstore to have over their PA system, an understandable concern. After her reading we were asked that if we were going to read racier scenes, to read them off-mic, since there were children in the store.

Wonderful YA author Mindy Raf read a scene from her recent The Symptoms of My Insanity. It was less than a sex scene. It was more than a kissing scene. It was uncomfortable and funny. It was specific and evocative. It was messy and brilliant. It was too much for the children’s bookstore to have over their PA system, an understandable concern. After her reading we were asked that if we were going to read racier scenes, to read them off-mic, since there were children in the store.This is a reasonable request. It’s a kid’s store, there are little ones, and our books, like a lot of YA books, were not necessarily appropriate for too young an audience. They didn’t kick us out or treat us disrespectfully. But it was a unique experience and there was something bigger at play, too, in my opinion. What was uncomfortable about Mindy’s scene was its break from the YA sexuality narrative.

Relationship narratives are something I’m thinking about a lot lately. Maybe because I’m in my thirties and in a relationship and am wondering what I am Supposed to be Doing. Maybe because I write about girls beginning to navigate relationships in unexpected ways.

I’m thinking a lot about how the things we see and read intersect with what’s expected of us in life. Lucky for 30-something women, we know exactly what the narrative is in literature and other entertainment for adults. We know what is expected of us if we are to follow the narrative presented in popular fiction. Meet, fall in love, get married. There is an implied goal to every relationship. And an endpoint that signifies the story is almost over. Marriage. It’s what the characters are working towards, and what the reader is instructed to root for, and—if we’re to believe stories and the way they’re told have an impact on our psyches—what we then hope for ourselves. We come to learn that a relationship has a shape, one shape, and that we need to be trying to fit into it.

I’d argue YA literature and media often do the same thing with sex.

It’s important to say that there are thousands of YA books that veer from a traditional relationship narrative. YA is growing and vast and a lot of writers are telling new stories and using sexuality in new ways to create new structures.

That said, a lot of stories aren’t doing this, and it’s meaningful to think about what the predominant place of sex in stories for teens is, and why it’s there. Sex is often used as endpoint in YA, in a similar way that marriage is used as an endpoint in adult literature and media. Sometimes it is heralded as a relationship accomplishment, or sometimes it’s the starting point of a more difficult story about the ways sex can go wrong, but it’s a fixed point around which other things revolve.

And maybe most meaningfully, when we’re talking about sex in YA, we’re talking almost exclusively about about intercourse.

YA relationships often have their own specific shape: meet, fall in like, first kiss, fall in love, first time having intercourse.

There is no messy in between.

And when there is, we’re uncomfortable with it.

A relationship in YA often moves to the Next Level with those two points of sexual contact—kissing and sex. Take Dawson’s Creek. This is neither literature nor incredibly current, but it’s a really strong example of the structure I’m talking about, and who doesn’t like a quick discussion of late 90s pop culture?

The characters in Dawson’s Creek have a first kiss, are boyfriend and girlfriend, and then angst about whether or not to have intercourse. As far as we know, they do not hit any other points of sexuality. They go from making out on the couch, fully clothed to sex, with nothing in between. They don’t worry about the other steps one could take, the other paths that occur while teens are figuring out how lust functions. They kiss and they have sex. If two characters wake up in the morning next to each other, naked, they’ve had intercourse. We know this to be true because it has always been true and the shape is ingrained in us.

We don’t even need to see or read about the sex happening. There’s a fade to black (or in the case of Dawson’s Creek, a fade to a snow globe of Los Angeles) and we understand that if a shirt has been removed or a bed is present, intercourse has occurred.

If two adult characters are in love, have slept together and have gotten through 1-5 difficult obstacles, we need them to get married. It is the conclusion to the journey. It is an answer to a question. It is a tangible, solid thing that we can understand very specifically—this means they are committed to each other forever and will have a family. We are comfortable with this story.

It’s problematic for adults. Marriage isn’t a tangible thing.

But sex? Sex is even less tangible. And the journey there is even less defined, in real life. Sex isn’t an answer at all. It isn’t even a prolonged state, the way marriage usually is. If the marriage Relationship Narrative is problematic and insincere and deceptive, the sex Relationship Narrative for teens is downright criminal. It’s a lie.

Here’s the harder thing to say: I’m guilty of this. It’s important for me to acknowledge this. A misconception about identifying as feminist is that you think you have all the answers to gender and sexuality issues. That you Do It Right. For me, for most feminists I think, that’s not the case. I’m the kind of feminist who is still training herself to see things through the right filter. I mess up, often. I play into familiar tropes and struggle to maintain both my own values and good storytelling and market viability. I have trouble even seeing where my own prejudices are, where I’ve fallen into the same traps as everyone else. Where and how and why I’ve given in to a dangerous structure.

I haven’t yet written the hooking up without intercourse stage of teen sexuality into my books. I’ve cut to black on actual sex. I’ve had the kissing and the implied understanding that sex has occurred and that the relationship is stronger because of it, more valid because of it. I’ve avoided letting my characters explore the messiness of sexuality. To be honest, I think I’m not sure how to do it yet. I’m not comfortable with the line between realistic/honest and graphic or too erotic. It’s a fault of mine, and something to check in with constantly. I have not done a good enough job speaking to the truth of teen, female sexuality. But that checking in and owning up is what being feminist is about for me. Checking in on those reflexes and working on them. Analyzing them. Being open to other people’s analysis of them. Hoping I’ll do better, wondering why when I sit down to write, I don’t want to.

What I’m sure of is that it’s dangerous to tell women that the goal of a relationship, the only way for a relationship to be “real” is to get married. And I know that telling a girl that sexuality is only about intercourse is dangerous. I know that letting sex be a stand in for validating a teen relationship is dangerous. I know that I don’t want to see relationships , especially for teen girls, take only one shape, over and over, because reinforcing an idea with such a specific prescription is hard on all of us. And we have enough stories we tell about teen girls and the boxes they’re allowed to sit in. We don’t need any more.

I loved that uncomfortable moment in the bookstore with Mindy reading about body parts and discomfort and not-intercourse. I loved that there was a specificity and awareness of the main character’s body and the chaotic, hilarious, strange, upsetting, turned-on, conflicted feelings going on in her mind. There was a lack of clarity that felt so much truer than the abundance of clarity that I think we feel pressure to write into young adult sex scenes. Mindy’s non-sex scene captured a truer part of adolescence, something that we don’t want to see. That is not appropriate to be played over the PA system in a children’s bookstore. That makes people tense up and shift around and wonder if it’s okay to admit that there’s something aside from making out and fading to black while the characters have their first time.

I forget a lot of scenes people read in their books during these panels. I’m sure we all do. I will never forget Mindy’s. It was shocking not because it was so sexy or racy or graphic. It was shocking because it was real and because it was an under-represented point of view that still doesn’t have a place in the teen Relationship Narrative.

But like with all things YA, what matters is what the readers need and want and relate to. And although we’re uncomfortable with shifting the narrative, I think the girls aren’t. Even teen Corey, I think, related more to the grey area than anything.

But like with all things YA, what matters is what the readers need and want and relate to. And although we’re uncomfortable with shifting the narrative, I think the girls aren’t. Even teen Corey, I think, related more to the grey area than anything.What’s the scene of female sexuality I remember most from my own reading when I was young? Deenie by Judy Blume. A guy attempting to feel her up with her brace on. I believe it was in a hallway. It brought up two feelings for me at the time—the bubbling up of lust and the frantic spiraling of anxiety. The fear and hope. The weird mix of wanting it for myself and being terrified it would someday actually happen in my life.

Re-reading it now, it’s a small, subtle moment. That’s fine. That’s great! Judy Blume did, years ago, what I am struggling to do now. Make clear that there is more to sexuality than only kissing and intercourse in an understandable, simple, clear way that didn’t defy the tone of the book by being “too graphic” (whatever that means). She managed honesty and frankness while maintaining a boundary that she as a writer, and me as a young reader, felt comfortable with. It’s a tiny, masterful moment that makes me want to do better.

We can’t all be Judy Blume. Or really none of us can, but the fact that we all agree she is the queen of navigating sexuality as a teen means there’s probably something to learn there. She didn’t trap us into one notion of what a relationship looked like, and she didn’t tell us sex was a goal that meant a relationship was real or valid or that a happily-ever-after was coming. She didn’t insist there was only the first kiss and the first time with nothing in between. She didn’t seem to have an agenda.

And listen, sex as a teen can make love feel more real, can bring a relationship to the next level. Of course it can! Just as marriage can work out and it can be a valid goal for a 20, 30 40 or whatever-something woman. But examining what literature and media are telling us is vital. And understanding our wants in that context elevates our understanding of ourselves. We have to give teens the chance to evaluate themselves in the same way.

YA literature has a responsibility to make a space for girls to think about sexuality on a broad spectrum. We owe it to girls to give them something we don’t have—more than one ideal Relationship Narrative. Open space where there used to be claustrophobic one-path hallways. A chance to decide for themselves what love looks like, and what sex looks like in all its forms.

***

Corey Ann Haydu is the author of OCD Love Story and the forthcoming Life By Committee, available in May.

Related StoriesThe Unlikable Female Protagonist: A Field Guide to Identification in the Wild -- Guest Post by Sarah McCarryWhose Feminism(s)?: Guest Post by Kirstin Cronn-MillsI love "unlikable," I write "unlikable," and I am "unlikable": Justina Ireland on "Unlikable" Girls

Related StoriesThe Unlikable Female Protagonist: A Field Guide to Identification in the Wild -- Guest Post by Sarah McCarryWhose Feminism(s)?: Guest Post by Kirstin Cronn-MillsI love "unlikable," I write "unlikable," and I am "unlikable": Justina Ireland on "Unlikable" Girls

Published on March 16, 2014 22:00

March 14, 2014

A Whirlwind Trip to PLA 2014, "About the Girls," + Other Musings

I just got back from a whirlwind trip down to Indianapolis to present at the Public Library Association conference. When I say whirlwind, I really mean it. My plans went a little askew because of a winter storm, but in the end, we made it down to Indy Wednesday evening and I made it back to my house in Wisconsin on Friday morning.

PLA was too short for the amount of fun it was. And I think this is the first time ever that I've felt presenting at a conference was completely fun without some kind of attachment to it. I didn't feel nervous like I have in the past. It felt comfortable and good, and both of those things coalesced into making the experience so enjoyable.

After arriving on Wednesday night, I got to see both Angie Manfredi and Sophie Brookover. Angie and I made a quick trip through the exhibit halls -- where I got to surprise and be surprised by seeing a friend there when neither of us knew the other was going -- and let me just say that PLA exhibits are fun, low key, and enjoyable. This isn't ALA exhibit opening night. This opening night involved enjoying some pita, hummus, spiced chicken, baba ghanoush, and some dessert. We picked up a few galleys, chatted with the vendors, and had this excellent picture snapped and shared by Penguin:

We didn't stick around long, and I went out to dinner with Sophie afterward to have a power chat and talk a tiny bit about our morning presentation on "new adult" fiction. We went back to our room after and shared some of Wisconsin's finest beer (because when I can travel somewhere by car, I'm going to bring my state's finest).

The nice thing about an 11 am presentation was the luxury of being able to sleep in and take it easy in the morning, which we all did. But then we made our way over to the convention center to give our talk on "new adult" fiction.