Kelly Jensen's Blog, page 113

May 22, 2014

May Debut YA Novels

Time to sink your teeth into this month's debut YA novels. Like usual, I'm sticking to the very strict definition of debut: it is the author's first novel ever. I did not include any novels that were the author's first YA title or their first under a pseudonym. I did include one novel this month that was published abroad last year and is being published for the first time in the US since it was her first novel.

As usual, it's possible I've missed a major title or two, so feel free to let me know in the comments. All descriptions are from WorldCat unless otherwise noted.

Camelot Burning by Kathryn Rose: Eighteen-year-old Vivienne, lady-in-waiting to the future queen Guinevere, is secretly apprenticed to Merlin the magician and helps him try to create a steam-powered metal beast to defeat Morgan La Fey, King Arthur's sorceress sister, when she declares war on Camelot.

Infinite Sky by CJ Flood: When Iris' mum leaves home, her brother, Sam, goes off the rails and her dad is left trying to hold it all together. So when a family of travellers sets up camp illegally in front of their farm, its the catalyst for a stand-off that can only end in disaster. But to Iris it's an adventure. She secretly strikes up a friendship with the gypsy boy, Trick, and discovers home can be something as simple as a carved out circle in a field of corn. (Via Goodreads).

These Gentle Wounds by Helene Dunbar: Fifteen-year-old Gordie is trying to build a new life after tragically losing his family, but when his abusive father returns, Gordie must confront the traumas of the past.

End Times by Anna Schumacher: When life in Detroit becomes too hard to bear, Daphne flees to her Uncle Floyd's home in Carbon County, Wyoming, but instead of solace she finds tumult as the townsfolk declare that the End Times are here, and she may be the only person who can read the signs and know the truth.

Oblivion by Sasha Dawn: Sixteen-year-old Callie Knowles fights her compulsion to write constantly, even on herself, as she struggles to cope with foster care, her mother's life in a mental institution, and her belief that she killed her father, a minister, who has been missing for a year.

One Man Guy by Michael Barakiva: When Alek's high-achieving, Armenian-American parents send him to summer school, he thinks his summer is ruined. But then he meets Ethan, who opens his world in a series of truly unexpected ways.

A Girl Called Fearless by Catherine Linka: After a synthetic hormone in beef kills fifty million American women, seventeen-year-old Avie struggles for a normal life in a world where teenage girls are a valuable commodity, but when her father contracts her to marry a rich, older man, Avie decides to run away with her childhood friend and revolutionary, Yates.

The Falconer by Elizabeth May: Lady Aileana Kameron, the only daughter of the Marquess of Douglas, was destined for a life carefully planned around Edinburgh's social events - right up until a faery killed her mother. Now it's the 1844 winter season and Aileana slaughters faeries in secret, in between the endless round of parties, tea and balls. Armed with modified percussion pistols and explosives, she sheds her aristocratic facade every night to go hunting. She's determined to track down the faery who murdered her mother, and to destroy any who prey on humans in the city's many dark alleyways. But the balance between high society and her private war is a delicate one, and as the fae infiltrate the ballroom and Aileana's father returns home, she has decisions to make. How much is she willing to lose - and just how far will Aileana go for revenge? Kimberly's Review.

Wish You Were Italian by Kristin Rae: Seventeen-year-old Pippa Preston, sent to Italy for a three-month art history program, decides instead to see the country on her own, armed with a list of such goals as eating an entire pizza and falling in love with an Italian, but soon finds herself attracted both to a dangerous local boy and an American archaeology student.

Killing Ruby Rose by Jessie Humphries: Ruby Rose, a 17-year-old Southern California girl known for her killer looks and killer SAT scores, becomes a vigilante who is also being hunted.

The Eighth Guardian by Meredith McCardle: Amanda Obermann. Code name Iris. It’s Testing Day. The day that comes without warning, the day when all juniors and seniors at The Peel Academy undergo a series of intense physical and psychological tests to see if they’re ready to graduate and become government operatives. Amanda and her boyfriend Abe are top students, and they’ve just endured thirty-six hours of testing. But they’re juniors and don’t expect to graduate. That’ll happen next year, when they plan to join the CIA—together. But when the graduates are announced, the results are shocking. Amanda has been chosen—the first junior in decades. And she receives the opportunity of a lifetime: to join a secret government organization called the Annum Guard and travel through time to change the course of history. But in order to become the Eighth Guardian in this exclusive group, Amanda must say good-bye to everything—her name, her family, and even Abe—forever. Who is really behind the Annum Guard? And can she trust them with her life? (via Goodreads).

Related StoriesThe Ring and the Crown by Melissa de la CruzFree to Fall by Lauren MillerGet Genrefied: Historical Fantasy

Related StoriesThe Ring and the Crown by Melissa de la CruzFree to Fall by Lauren MillerGet Genrefied: Historical Fantasy

Published on May 22, 2014 22:00

May 21, 2014

While We Run by Karen Healey

Karen Healey writes killer speculative fiction. I think I liked

While We Run

even better than I liked the first book, which was fantastic anyway. When We Wake had an ending, but an open-ended one, making this sequel welcome but not required. This time, the story is told from Abdi's point of view, and it begins a few months after the first book ended. I don't want to share too much, but I will say that things aren't great - Abdi and Tegan are in government custody and are being manipulated and tortured into being mouthpieces. They have a plan to get away - but at what cost? And what will they need to do once they're free?

Karen Healey writes killer speculative fiction. I think I liked

While We Run

even better than I liked the first book, which was fantastic anyway. When We Wake had an ending, but an open-ended one, making this sequel welcome but not required. This time, the story is told from Abdi's point of view, and it begins a few months after the first book ended. I don't want to share too much, but I will say that things aren't great - Abdi and Tegan are in government custody and are being manipulated and tortured into being mouthpieces. They have a plan to get away - but at what cost? And what will they need to do once they're free?Much of what makes dystopias so powerful is their connection to our own present-day issues. If you read a synopsis of a dystopia and it makes you roll your eyes, it's probably because the premise lacks this connection. This is not the speculative fiction Healey writes. Her future world is believable because of the way it differs from the present. She's taken the issues we grapple with now (or avoid grappling with now) and shown how they could progress, how they could worsen - or perhaps get better. She doesn't focus on any one thing, either, addressing climate change, government and corporate power, class, race, the effects of colonialism and globalization. The result is a complex future world with a variety of problems big and small, and a diverse group of people struggling with them.

Abdi and Tegan grapple with so very much in this volume. Is collateral damage - any amount - acceptable, even for a just cause? Is complete recovery from trauma possible? At what point does reading people too well become manipulation? How the heck do you fix a world? This stuff is hard. In some cases, there aren't any good answers. It's a lot for teenagers to handle; it's also precisely the kind of thing teen readers see going on in their world.

From a thematic standpoint, this book rocks it. From a craft standpoint, it's terrific as well. Abdi's narrative is heartbreaking at times. I feel like sometimes writers of dystopias will have their characters go through really horrible stuff and then gloss over any sort of lasting effects it may have. Healey refuses to do this - it's obvious Abdi is traumatized by his time in captivity and Healey lets him go through it. She makes us as readers feel it, too. And of course, the plot, which features cryonics and lots of government secrets, is exciting and well-paced, too.

Many of the characters from When We Wake return in the sequel, which means the book is quite diverse. Abdi is a black protagonist, an atheist, the son of Muslims. His three friends are a white semi-religious Christian girl (Tegan), a devout Muslim girl (Bethari), and a transgender girl (Joph). Far from feeling like a checklist, this cast simply feels like the people who exist. You know, the people you see when you take a look at your own community.

Readers who may feel they've exceeded their threshold for dystopias and books featuring shitty futures would do well to take a look at this series, which breathes new life into the subgenre. It's worlds removed from books that bear a striking resemblance to this fun little joke.

Review copy received from the publisher. While We Run is available May 27.

Related StoriesFree to Fall by Lauren MillerCress by Marissa MeyerEverything Leads to You by Nina LaCour

Related StoriesFree to Fall by Lauren MillerCress by Marissa MeyerEverything Leads to You by Nina LaCour

Published on May 21, 2014 22:00

May 20, 2014

Life By Committee by Corey Ann Haydu

Tabitha is lonely.

Tabitha is lonely.Over the last few months -- the last year or so, really -- things in her life have changed quite a bit. Her parents, who had her when they were mere teenagers themselves, are expecting a new baby. Tab's body has changed significantly, too. She's developed a shape, including boobs, that have garnered attention. She's gotten so much attention, in fact, that it's the reason her former friends have ditched her. They think she's turned into a slutty girl, now that she's got the appearance of one.

And maybe Tab has changed more than just in her appearance. She can't seem to stop thinking about Joe, the boy who has a girlfriend named Sasha.

The boy who admitted to liking her late one night.

The boy who kissed her.

Enter Life By Committee: an anonymous, online group of teens who make a deal to keep each other's secrets safe and secure in exchange for following through with an assignment meant to help the secret teller stretch him or herself. There is a time limit to completing the assignments and failure to complete means those secrets may not be kept safe.

Tab finds Life By Committee by accident. She's obsessed with note taking in novels -- her way of close reading -- and she likes to then exchange the book she's written in for copies of other favorite books to see what other people have written in the margins. It was in flipping through a used copy of The Secret Garden her dad picked up for her she found out about the site.

Corey Ann Haydu's sophomore novel Life By Committee tackles some interesting aspects of growing up and learning how to navigate the social dynamics that accompany physical change. Tab lives in a small Vermont town where everyone knows everyone else, or so it seems. When her body begins to develop, she's on the outs with her friends because of the assumptions they make about what her having that sort of body means. Because she's blonde and because she's well-developed, they believe she's heading on a path that means she's more interested in the attention of boys than she is in being a friend.

In some ways, her friends are right and in other ways, they're not. Their assumptions impress ideas upon Tabitha, who is indeed interested in boys, including Joe. But Tab also has another boy she's been interested in, and he happens to be the brother of one of her now-former best friends. So indeed, she is interested in boys, but her interest in them isn't at the level her friends have suggested. Because we're inside Tabitha's mind, too, we're able to see where she begins to struggle with the perception of who she is and the reality of who she is and what she wants.

She likes these boys, but she's torn about how much she likes them and why she likes them. Physical contact with Joe feels nice, but the emotional intimacy she develops with him via their online chats is nice too. She's well-aware, too, of what comes with Joe: his girlfriend Sasha. Does Tab feel bad about making out with a boy who is taken? Yes and no. She knows it's not right, but she also believes Joe when he tells her he's not that into Sasha anymore.

When Tab dives into Life By Committee, her first assignment comes as a result of her admitting to kissing Joe even though he has a girlfriend. She's told she needs to kiss him again, and she does. While she doesn't do it immediately, she does complete the job before deadline, and in doing so, she's afforded more opportunity to think about what it is she may want in a relationship with him.

Her second secret and second assignment has to do with her father, who has a problem with smoking pot. This secret, one that Tab held deep inside her, is met with the assignment that she's to smoke pot with him. It's not meant to get her high nor meant to show her some new side of why he chooses to do what he does to cope with life; it's instead meant to be a wakeup call to her father -- and it becomes just that, too.

What Tab takes from Life By Committee, though, isn't so much the secret-telling and the assignment-completing. It's instead a sense of community. Even though she's at a distance, she finds herself drawn to the other anonymous people partaking in this online group. Who are they? What do their secrets say about them? How and where are they able to complete these assignments and what does success for them look like beyond the assignments? Are they finding love? Happiness? Creative fulfillment?

The idea of Life By Committee comes together in the end of the book, and because it'd be spoiler to explain what happened, I won't. I will say I saw it coming from pretty far away, and I felt that it was almost too neat a bow on top of the story. I don't know if that will be the case for all readers, particularly teens, who might see the ending as the kind of outcome Tabitha deserved to have for herself. For me, the idea of Life By Committee more broadly felt a little too convenient and a little too styled in terms of crafting a bigger narrative arc than I prefer. It wasn't that it was too easy for Tabitha, but rather, it felt a little too easy for getting Tabitha from point A to point B in the story.

Life By Committee's strength lies in its character development and in the way it renders how painful it is to feel lonely and like you do not have friends you can rely on. But it's done in a way that's smart: Tabitha isn't necessarily an easily likable character, but she's easy to feel sympathy and empathy for. This is a girl who is knowingly pursuing a boy who has a girlfriend and Tabitha seems determined to find every bit of Sasha that's repulsive or annoying and pack it away as evidence for why it's okay for her to pursue Joe -- even though she knows deep down it's not okay. At the same time, Joe leads Tab on very clearly, and it's hard to dislike what she does completely because she's getting all the cues that it's okay with him. Likewise, Tab's home life and the changes to come soon because of the new baby, only make her emotional and mental states more complex.

Haydu does well in tackling the complicated body image elements with Tab. In many ways, it was novel to read a book where one becomes so conscious of themselves and the physical changes they're going through in a way that's not about weight. It's about shape and about the way people react to one another during puberty. In many ways, this hit really close to home for me: Tab talks about clothing and how now that she has a different shape, people have commented upon how it's not appropriate for her to be wearing certain things because it could draw unwanted attention. As a girl who developed large breasts when I was young, this is something I found myself being told quite a bit, and it was something that always made me feel a sense of shame because so little could deemphasize the fact my body now had a new shape. That shame and that sense of wanting to crawl inside yourself because of changes you have absolutely no control over were palpable through Tab and her experiences.

Some of the secondary characters weren't fully developed, and I didn't necessarily find myself compelled by the budding romance in the story -- either the one Tab has with Joe (if that could be considered a romance) or the one that we find out may exist between Tab and another boy. I wanted to get to know Sasha better, primarily because I felt she was redeemed later on in the story in such a way that she seemed like a really interesting character. Tab's limited perspective and insight on her as simply the weird girl who is Joe's girlfriend left me wanting a little more.

Pass Life By Committee on to readers who like realistic YA and who are particularly eager for stories about friendship -- or what happens when friendships go sour. Perhaps more than a book about friendship, Haydu's novel is really about peer relationships and the sorts of feedback loops that exist within them. Fans of Siobhan Vivian should really enjoy Life By Committee.

Review copy received from the publisher. Life By Committee is available now.

Related StoriesFree to Fall by Lauren MillerCress by Marissa MeyerEverything Leads to You by Nina LaCour

Related StoriesFree to Fall by Lauren MillerCress by Marissa MeyerEverything Leads to You by Nina LaCour

Published on May 20, 2014 22:00

May 19, 2014

The Ring and the Crown by Melissa de la Cruz

Have you ever read a book that you know intellectually isn’t very good, but you rather enjoy it anyway? That’s how

The Ring and the Crown

was for me. I don’t mean it’s not good in terms of content – often I’ll hear people say that romances or chicklit are their guilty pleasures, and that’s not what I mean at all. I mean the writing just isn’t great. It’s 90% exposition, full of telling, all of the fun stuff happens off the page, the pacing is poor. We're told what characters are like instead of reading it in their words and actions. There’s a lot that’s not done well.

Have you ever read a book that you know intellectually isn’t very good, but you rather enjoy it anyway? That’s how

The Ring and the Crown

was for me. I don’t mean it’s not good in terms of content – often I’ll hear people say that romances or chicklit are their guilty pleasures, and that’s not what I mean at all. I mean the writing just isn’t great. It’s 90% exposition, full of telling, all of the fun stuff happens off the page, the pacing is poor. We're told what characters are like instead of reading it in their words and actions. There’s a lot that’s not done well.And yet, I was mostly entertained by it. Here’s the gist: It’s the early 20th century (in an alternate world where magic exists), and Marie-Victoria, princess and heir to the throne of England, has just been told by her mother, Queen Eleanor, that she is to wed Leopold, the prince and heir to the throne of Prussia. This royal marriage will put an end to the war that’s raged between the two countries for the past several years. Marie-Victoria is none too thrilled about it, as she’s in love with a soldier named Gill and rather detests Leopold, whom she finds spoiled and mean.

Marie-Victoria is probably what I would consider the main protagonist, but she’s actually only one of five points of view in the story. The others are: Aelwyn, the daughter of the Merlin (a title rather than a name), a magician who serves (and controls) the crown; Ronan, an American whose once-wealthy family now depends on her finding a rich husband in London in order to save them from insolvency; Wolfgang, the younger brother of Leopold; and Isabelle, Leopold’s former French fiancée. Each of the characters schemes about something, and their relationships with each other become increasingly entangled as the book progresses. Magic is present, but it’s more of a background feature.

Despite its problems, the book held my interest, and I may even read a sequel (if there is one). I think its success in that regard has a lot to do with the frequent POV shifts. Just as I thought I might be tiring of this particular character’s post-party reflections of a certain event (an event which happened off the page, of course), de la Cruz would switch to a different character, and my interest would re-engage. There are some faint hints that some things are not as they seem, as well, so I was interested to see what exactly would shake out by the end. Things do shake out eventually, but it happens all in a rush, and it’s a long time coming. It makes the first 90% of the book seem like set-up. There are very few people who relish reading a book that’s almost entirely exposition.

Readers looking for action-heavy historical fantasy more along the lines of The Burning Sky would do better to look elsewhere. There’s almost no action here, and what little there is takes place off the page. I don’t require action, but I do require stuff to happen, and I want to see it happening rather than be told about it after the fact. Even the climax is told instead of shown – one character tells another what he did rather than experiencing it for the reader. Too bad. In those few times when de la Cruz does show us things, rather than tell us about them as a sort of afterthought, the book verges on exciting.

Still, this will certainly hold appeal for some readers, perhaps those who have enjoyed the Downton Abbey-esque Cinders & Sapphires. There’s a large cast of aristocratic characters with their own POVs, relationships are messy, and much of the plot focuses on fancy society and its peculiar brand of rules and manners. Plus, it’s set during the Downton Abbey time frame. Alternate history junkies may also get a kick out of how de la Cruz’s world with magic differs from our own (the United States lost the Revolutionary War, for instance).

Finished copy received from the publisher. The Ring and the Crown is available now.

Related StoriesFree to Fall by Lauren MillerCress by Marissa MeyerEverything Leads to You by Nina LaCour

Related StoriesFree to Fall by Lauren MillerCress by Marissa MeyerEverything Leads to You by Nina LaCour

Published on May 19, 2014 22:00

May 18, 2014

Hardcover to Paperback: 5 YA Changes to Consider

Another season of catalogs means another round of YA books getting new looks in their paperback editions. Some of these cover changes are good ones, while other ones seem to miss the mark. In addition to the four books I'm rounded up to talk about, I thought it would be fun to also include a book that got not one, not two, but three different cover designs before it even got published (and it's not publishing until this summer, so it may even see another one).

As always, I'd love your thoughts on any of the changes, and I'd love to see if you've found any recent changes worth nothing. Original hardcover designs are on the left, with their paperback redesigns on the right.

The recovering of Lauren DeStefano's Perfect Ruit is not only one I'm behind, but I think the paperback edition might be one of my favorite covers in a long, long time. The hardcover isn't bad, but it's pretty similar to a lot of other covers in YA right now. It's a girl in a dress, and the design around here looks sort of steampunk, even though it's a utopian novel. The font for the title isn't my favorite; the "Perfect" lettering is too boxy and stiff, and that's carried over into the author's name, too. While I don't mind the way "Ruin" looks, I don't like how the bottom of part of the "R" is cut off for the line running from the bottom of "N" and down around the edge of the cover and back.

If you look closer at the original cover, there's a lot going on. There's a couple of dangling keys, a firefly, constellations in the background, and what look like small ornaments hanging in the tree branches above the girl's head. They're a little obscured for me because my eye is drawn right to the center of the cover, to the bright red "Ruin" and red dress the girl is wearing. I suspect those small elements play a role in the story, but it's very easy to overlook them.

The paperback for Perfect Ruin though -- it's eye-catching in its minimalism. The all-black background with a crisp, white bird statue being shattered is immediate and it's immediately captivating. The smaller-than-expected title done in all white, along with the smaller-than-expected author name is understated to a great effect. While the cover doesn't tell a whole lot about the story, it's engaging and piques my curiosity. I know there's a story here, and I want to know why what looks like perfection in the form of that ceramic bird has been shattered. This is an excellent redesign, and the companion book, Burning Kingdoms, is getting a similarly striking design.

Perfect Ruin will be available in paperback March 2015.

I read Julie Berry's All The Truth That's in Me last year and felt pretty middle-of-the-road about it. Great writing, but the story itself didn't necessarily work for me, and I found the ambiguous time period setting to be more irritating than creative. That translated to how I felt about the cover, too. The girl on the cover has a very modern look to her in terms of how she's wearing her hair and her makeup (the dark eyes especially). She didn't match up with the image of the main character I had in the least. More, though, the girl on the cover is wearing an ambiguous shirt that could either translate into something that members of a cult might wear -- that's fitting, maybe, with the story -- or as an outfit worn during a specific historical period of time, which would contradict the very modern style of the girl's makeup and hair. The cover doesn't tell readers more about the story than the story does, and in this case, some of the questions I had and other readers had (via reviews) aren't cleared up.

What does work on the cover is the tear across the girl's mouth. That's a huge part of the story, and I think the design nails it. This is a book that digs into what it means to be silenced and what it means when your capacity to speak up is taken from you, and I think it's conveyed here.

In paperback, the book has an entirely different look and feel to it. The girl is gone, replaced instead by a flower. There's one petal that isn't "pretty" like the rest of them, as it looks like it's infected. Gone is the blurb on this cover, replaced with a tag line that's more interesting: "Her words could ruin him, but her silence will destroy them both." While I think the tag line does tell the story, I think it's a little too "sexy" for what the story actually is about. I'm not a huge fan of the gold font, nor the gold coloring of the flower, as I think it might be trying to convey that ambiguous time period setting again.

Maybe most interesting to me is that the paperback looks like it's appealing to an entirely different readership than the hardcover is. The hardcover looks like many other YA titles (big face of a girl style), whereas the paperback looks much more literary and like the kind of book you'd find in the adult section of a bookstore or library. I suspect without the girl, it might better reach adult readers, who will be curious what the story could be about since the cover doesn't tell you a whole lot. This is a good cover -- better than the hardcover, I think -- but it's not necessarily one that gives a whole lot of insight into the story. In this case, that might be a positive thing, as it's also not further complicating some of the story's unanswered questions.

The paperback edition of Berry's All The Truth That's in Me will be available August 14, 2014.

I'm not sure what to make of the redesign of Lauren Kate's Teardrop. The hardcover for this one is pretty standard, popular YA cover design. It's not bad, but it's not necessarily the most memorable or striking. The thing is: it works. The readers who are fans of Kate's work will know this is the book for them and be drawn to it.

The paperback redesign, though, is even less memorable. It's a giant face, with a closeup of a blue eye, and the title of the book is made so huge to take away from the image behind it. The new design adds a tag line that isn't on the hardcover -- "One tear can end the world" -- which doesn't really tell readers a whole lot, either. The author's name is in a crisper font, but beyond that, I'm not sure this cover is any better than the hardcover. In fact, I would say that the hardcover in this case does better at speaking to teen readers who love these kinds of books. The paperback doesn't even offer a pretty dress (one that's disappearing!) to enjoy.

Teardrop will be available in paperback October 28, 2014. The hardcover of book two in the series, Waterfall, will be available the same day and carry the same design to it: a big face with a big title.

I think books that are published at the very end of the year can be easily missed. Part of it is that it's just a busy time of the year, and part of it -- at least in library and school land -- is budget cycle. If you're in a library that requires trade reviews for books, and your budget needs to be spent before the end of the year, it's easy to not know about the December books unless there's huge marketing behind them.

Audrey Couloumbis's Not Exactly A Love Story came out in December 2012 and . . . I didn't even know this book existed until I was doing some catalog browsing for cover changes to write about. Reading the description and looking at the original cover, it's not clear this is a historical novel in the least (it's set in 1977). The title doesn't tell a whole lot about it either, except that it's not your typical love story, despite the fact the image on the cover is of a couple partaking in what could be called a typical love story embrace. The color choices in the cover and the use of non-standard shapes to highlight some of the words in the title are jarring. This isn't your standard YA cover, but it's also not the most appealing one. Perhaps that's because it doesn't look like every other cover. I would see a good argument that this design dates the cover in a way that might be telling of the story's setting.

When I saw the paperback edition of the book, my first thought was that it was going for the Eleanor & Park look and low and behold, the description for this book in Edelweiss said this: "This quirky, flirty, and smart story will appeal to fans of Frank Portman's King Dork, John Green's An Abundance of Katherines, and Rainbow Rowell's Eleanor and Park." They know exactly what audience they want to target with this new look, and I think they nail it. As I've talked about before, there's no question that the new trend is to compare everything to Green and Rowell and that cover designs are increasingly trying to mimic the illustrated covers of Rowell's books.

I quite like the new look, and I dig how the houses sort of look like faces that are close to one another (this is maybe more obvious with the house on the left than the one on the right). I like the use of the landlines in the lit-up rooms of both homes, and I think the font that was used for the title gives a sweetness that is missing in the original cover. Interestingly, I think that the redesigned cover appeals to a much younger audience than the original cover does. Perhaps because of how it's designed, how the focus is less on the paper or the love story, and how the font selection and starry sky just look like many a middle grade novel.

Not Exactly A Love Story will be available in paperback July 22.

The final cover redesigns I wanted to talk about are for a book not even out yet: Miranda Kenneally's Breathe, Annie, Breathe. The cover on the far left was the first iteration, and it mirrored the trend of illustrated designs. It was interesting to watch the feedback that came from readers on this cover. While it wasn't disliked, it didn't match the other books Kenneally had written. Though this new book is set in the same world as Kenneally's others, the books aren't sequels. They don't need to look alike, but many readers wanted them to maintain a similar look and I agree -- at least when it comes to reader's advisory and when it comes to getting books into the hands of teens, having that similar look helps a lot. This is especially true when you're time-strapped or can't read all of the books out there (who can?). The cover here isn't bad, but it's unexpected and contrasts with the look and feel of Kenneally's other books. Note the tag line: "The finish line is only the beginning."

The cover in the middle was the second iteration, and it looked much more like the rest of the books set in this world than the first cover. We know this is going to be a novel about an athletic girl. It's not necessarily the most memorable, but it fits both the story description and the world in which the story is set. Not the tagline: "Sometimes letting go is the only way to hold on." That's quite different than the initial tag line.

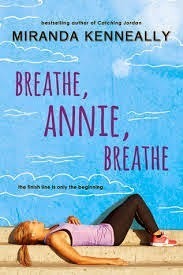

Just days after the second cover was revealed, a third redesign came up for the book. This one might be the best one, though: it not only fits the rest of the books set in this world, but it's striking and memorable in a way that the second one wasn't. It's clear the girl is an athlete here, but what's most notable in the design is the large use of a blue background. It's bright and will stand out on shelves the way that the girl running into the distant sunset wouldn't. The design went back to the font used in the initial cover design, too, and to good effect. Perhaps this cover is the marriage of the illustrated cover -- the clouds on the blue background -- with the stock image cover -- the girl on the ground, post-run. Tag line: "The finish line is only the beginning . . .". The tag line works well with this cover, and I kind of like that there's an ellipsis to round it out.

Breathe, Annie, Breathe will be available July 14, and worth noting: this is a hardcover release, whereas Kenneally's prior releases were paperback originals. Perhaps that was part of the initial decision-making in changing the cover look so drastically? Whatever the reason, I think the final compromise is the strongest.

Related StoriesCover Double, Triple, and (formerly) Quadruple: Risk Taking and Cover DesignHardcover to Paperback: YA Redesigns to ConsiderHardcover to Paperback: Six YA Redesigns to Consider

Related StoriesCover Double, Triple, and (formerly) Quadruple: Risk Taking and Cover DesignHardcover to Paperback: YA Redesigns to ConsiderHardcover to Paperback: Six YA Redesigns to Consider

As always, I'd love your thoughts on any of the changes, and I'd love to see if you've found any recent changes worth nothing. Original hardcover designs are on the left, with their paperback redesigns on the right.

The recovering of Lauren DeStefano's Perfect Ruit is not only one I'm behind, but I think the paperback edition might be one of my favorite covers in a long, long time. The hardcover isn't bad, but it's pretty similar to a lot of other covers in YA right now. It's a girl in a dress, and the design around here looks sort of steampunk, even though it's a utopian novel. The font for the title isn't my favorite; the "Perfect" lettering is too boxy and stiff, and that's carried over into the author's name, too. While I don't mind the way "Ruin" looks, I don't like how the bottom of part of the "R" is cut off for the line running from the bottom of "N" and down around the edge of the cover and back.

If you look closer at the original cover, there's a lot going on. There's a couple of dangling keys, a firefly, constellations in the background, and what look like small ornaments hanging in the tree branches above the girl's head. They're a little obscured for me because my eye is drawn right to the center of the cover, to the bright red "Ruin" and red dress the girl is wearing. I suspect those small elements play a role in the story, but it's very easy to overlook them.

The paperback for Perfect Ruin though -- it's eye-catching in its minimalism. The all-black background with a crisp, white bird statue being shattered is immediate and it's immediately captivating. The smaller-than-expected title done in all white, along with the smaller-than-expected author name is understated to a great effect. While the cover doesn't tell a whole lot about the story, it's engaging and piques my curiosity. I know there's a story here, and I want to know why what looks like perfection in the form of that ceramic bird has been shattered. This is an excellent redesign, and the companion book, Burning Kingdoms, is getting a similarly striking design.

Perfect Ruin will be available in paperback March 2015.

I read Julie Berry's All The Truth That's in Me last year and felt pretty middle-of-the-road about it. Great writing, but the story itself didn't necessarily work for me, and I found the ambiguous time period setting to be more irritating than creative. That translated to how I felt about the cover, too. The girl on the cover has a very modern look to her in terms of how she's wearing her hair and her makeup (the dark eyes especially). She didn't match up with the image of the main character I had in the least. More, though, the girl on the cover is wearing an ambiguous shirt that could either translate into something that members of a cult might wear -- that's fitting, maybe, with the story -- or as an outfit worn during a specific historical period of time, which would contradict the very modern style of the girl's makeup and hair. The cover doesn't tell readers more about the story than the story does, and in this case, some of the questions I had and other readers had (via reviews) aren't cleared up.

What does work on the cover is the tear across the girl's mouth. That's a huge part of the story, and I think the design nails it. This is a book that digs into what it means to be silenced and what it means when your capacity to speak up is taken from you, and I think it's conveyed here.

In paperback, the book has an entirely different look and feel to it. The girl is gone, replaced instead by a flower. There's one petal that isn't "pretty" like the rest of them, as it looks like it's infected. Gone is the blurb on this cover, replaced with a tag line that's more interesting: "Her words could ruin him, but her silence will destroy them both." While I think the tag line does tell the story, I think it's a little too "sexy" for what the story actually is about. I'm not a huge fan of the gold font, nor the gold coloring of the flower, as I think it might be trying to convey that ambiguous time period setting again.

Maybe most interesting to me is that the paperback looks like it's appealing to an entirely different readership than the hardcover is. The hardcover looks like many other YA titles (big face of a girl style), whereas the paperback looks much more literary and like the kind of book you'd find in the adult section of a bookstore or library. I suspect without the girl, it might better reach adult readers, who will be curious what the story could be about since the cover doesn't tell you a whole lot. This is a good cover -- better than the hardcover, I think -- but it's not necessarily one that gives a whole lot of insight into the story. In this case, that might be a positive thing, as it's also not further complicating some of the story's unanswered questions.

The paperback edition of Berry's All The Truth That's in Me will be available August 14, 2014.

I'm not sure what to make of the redesign of Lauren Kate's Teardrop. The hardcover for this one is pretty standard, popular YA cover design. It's not bad, but it's not necessarily the most memorable or striking. The thing is: it works. The readers who are fans of Kate's work will know this is the book for them and be drawn to it.

The paperback redesign, though, is even less memorable. It's a giant face, with a closeup of a blue eye, and the title of the book is made so huge to take away from the image behind it. The new design adds a tag line that isn't on the hardcover -- "One tear can end the world" -- which doesn't really tell readers a whole lot, either. The author's name is in a crisper font, but beyond that, I'm not sure this cover is any better than the hardcover. In fact, I would say that the hardcover in this case does better at speaking to teen readers who love these kinds of books. The paperback doesn't even offer a pretty dress (one that's disappearing!) to enjoy.

Teardrop will be available in paperback October 28, 2014. The hardcover of book two in the series, Waterfall, will be available the same day and carry the same design to it: a big face with a big title.

I think books that are published at the very end of the year can be easily missed. Part of it is that it's just a busy time of the year, and part of it -- at least in library and school land -- is budget cycle. If you're in a library that requires trade reviews for books, and your budget needs to be spent before the end of the year, it's easy to not know about the December books unless there's huge marketing behind them.

Audrey Couloumbis's Not Exactly A Love Story came out in December 2012 and . . . I didn't even know this book existed until I was doing some catalog browsing for cover changes to write about. Reading the description and looking at the original cover, it's not clear this is a historical novel in the least (it's set in 1977). The title doesn't tell a whole lot about it either, except that it's not your typical love story, despite the fact the image on the cover is of a couple partaking in what could be called a typical love story embrace. The color choices in the cover and the use of non-standard shapes to highlight some of the words in the title are jarring. This isn't your standard YA cover, but it's also not the most appealing one. Perhaps that's because it doesn't look like every other cover. I would see a good argument that this design dates the cover in a way that might be telling of the story's setting.

When I saw the paperback edition of the book, my first thought was that it was going for the Eleanor & Park look and low and behold, the description for this book in Edelweiss said this: "This quirky, flirty, and smart story will appeal to fans of Frank Portman's King Dork, John Green's An Abundance of Katherines, and Rainbow Rowell's Eleanor and Park." They know exactly what audience they want to target with this new look, and I think they nail it. As I've talked about before, there's no question that the new trend is to compare everything to Green and Rowell and that cover designs are increasingly trying to mimic the illustrated covers of Rowell's books.

I quite like the new look, and I dig how the houses sort of look like faces that are close to one another (this is maybe more obvious with the house on the left than the one on the right). I like the use of the landlines in the lit-up rooms of both homes, and I think the font that was used for the title gives a sweetness that is missing in the original cover. Interestingly, I think that the redesigned cover appeals to a much younger audience than the original cover does. Perhaps because of how it's designed, how the focus is less on the paper or the love story, and how the font selection and starry sky just look like many a middle grade novel.

Not Exactly A Love Story will be available in paperback July 22.

The final cover redesigns I wanted to talk about are for a book not even out yet: Miranda Kenneally's Breathe, Annie, Breathe. The cover on the far left was the first iteration, and it mirrored the trend of illustrated designs. It was interesting to watch the feedback that came from readers on this cover. While it wasn't disliked, it didn't match the other books Kenneally had written. Though this new book is set in the same world as Kenneally's others, the books aren't sequels. They don't need to look alike, but many readers wanted them to maintain a similar look and I agree -- at least when it comes to reader's advisory and when it comes to getting books into the hands of teens, having that similar look helps a lot. This is especially true when you're time-strapped or can't read all of the books out there (who can?). The cover here isn't bad, but it's unexpected and contrasts with the look and feel of Kenneally's other books. Note the tag line: "The finish line is only the beginning."

The cover in the middle was the second iteration, and it looked much more like the rest of the books set in this world than the first cover. We know this is going to be a novel about an athletic girl. It's not necessarily the most memorable, but it fits both the story description and the world in which the story is set. Not the tagline: "Sometimes letting go is the only way to hold on." That's quite different than the initial tag line.

Just days after the second cover was revealed, a third redesign came up for the book. This one might be the best one, though: it not only fits the rest of the books set in this world, but it's striking and memorable in a way that the second one wasn't. It's clear the girl is an athlete here, but what's most notable in the design is the large use of a blue background. It's bright and will stand out on shelves the way that the girl running into the distant sunset wouldn't. The design went back to the font used in the initial cover design, too, and to good effect. Perhaps this cover is the marriage of the illustrated cover -- the clouds on the blue background -- with the stock image cover -- the girl on the ground, post-run. Tag line: "The finish line is only the beginning . . .". The tag line works well with this cover, and I kind of like that there's an ellipsis to round it out.

Breathe, Annie, Breathe will be available July 14, and worth noting: this is a hardcover release, whereas Kenneally's prior releases were paperback originals. Perhaps that was part of the initial decision-making in changing the cover look so drastically? Whatever the reason, I think the final compromise is the strongest.

Related StoriesCover Double, Triple, and (formerly) Quadruple: Risk Taking and Cover DesignHardcover to Paperback: YA Redesigns to ConsiderHardcover to Paperback: Six YA Redesigns to Consider

Related StoriesCover Double, Triple, and (formerly) Quadruple: Risk Taking and Cover DesignHardcover to Paperback: YA Redesigns to ConsiderHardcover to Paperback: Six YA Redesigns to Consider

Published on May 18, 2014 22:00

May 16, 2014

Links of Note: May 17, 2014

Isn't this "Little House on the Prairie" cake great?

Isn't this "Little House on the Prairie" cake great? The last two weeks have been a whirlwind. I got back from the Connecticut Library Association conference to have a small number of days to get my head together and start work for Book Riot, and then I flew out to Virginia to learn more about my Book Riot work. I got back from that trip to a solid week -- this past one -- to settle into a nice routine, catch up on reading, and take care of personal stuff before I go on another trip starting Monday (this one a vacation for me). It's been such a blast, but my reading the internet has dipped a bit, so this links roundup is a little skimpy.

Have you read anything great lately around the web I should know about? Let me know in the comments! And also, I'd be remiss not to mention the new and fantastic Book Riot News, which is a reddit-style site for sharing book related news. If you want to share or get caught up on book-related news from around the web, you should check it out.

Did you know May is Mental Health Awareness Month? Stephanie Kuehn put together an excellent reading list of YA novels that delve into various mental health issues over on YA Highway. I haven't had the chance to play with this a whole lot, so I've got no idea how deep it goes, but this database is all about genre fiction by women. Hannah Gomez wrote this really thought-provoking post over on the Lee & Low blog asking where all of the people of color in dystopian novels have gone. This post by Molly Backes begging for people to stop complaining about Harry Potter -- and by extension, children's and young adult literature more broadly -- is excellent. It is the 9th annual 48 Hour Book Challenge hosted by Mother Reader, and you should sign up to participate. It's the first weekend in June, and this year, the focus is on diversity. I can't sign up to participate officially, but I do plan on spending plenty of time that weekend reading. The Book Smugglers are going to start publishing short stories. What an awesome idea. "Men Act, Women Appear" is a great read. Over at YA Series Insiders, Stacked was selected as blog of the month, and Kimberly did this really nice interview about when we started and how we do what we do here. This piece over at Forbes looking at the meta analysis Common Sense Media did that claimed teens aren't reading like they used to is pretty good. I especially enjoyed the part at the end, digging into gendered reading. Can you believe it's the eighth year for Kid Lit Con? This year, it's going to be in Sacramento in early October and the focus is on diversity and what bloggers and kid lit enthusiasts can do to make a difference. Here are the early details. I am pretty positive I'll be able to make it again this year and hope if you're in the area or are able to, you can, too.

Audiobook fan? Don't miss the kick off of this summer's Sync program, where you can download free audiobooks of classics *and* current YA titles every single week. This is such a neat program.

A few things I've written over at Book Riot:

I talked about the new Judy Blume covers (I can't get enough of the middle grade cover for Are You There God).These kid lit inspired cakes are so cool. I'm a big fan of the Charlotte's Web shower curtain you can pick up in Book Fetish. My "Beyond the Bestsellers" series looks at what you should read next or hand to fans of Sherman Alexie's The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian .

Related StoriesLinks of Note: May 3, 2014Links of Note: April 5, 2014Quick Saturday Links: March 29, 2014

Related StoriesLinks of Note: May 3, 2014Links of Note: April 5, 2014Quick Saturday Links: March 29, 2014

Published on May 16, 2014 22:00

May 15, 2014

Define "Reading"

A couple of really interesting studies have popped up recently.

First, this survey, done by the Reading Agency, notes that 63% of men feel like they aren't reading as much as they think they should and a full fifth of men admit to saying reading is difficult or they don't enjoy it.

NPR wrote about the findings Common Sense Media had when combing through a series of studies that teens aren't reading like they used to. This one cites a few reasons why this might be, including the rise of tablets and internet-connected devices, as well as the always-present "not enough time" (that's the big reason for the survey above on why men are reading less).

But before we cry about how no one is reading anymore, perhaps we should examine one of the biggest factors not examined in either of these studies: how is "reading" defined?

It appears in both cases that "reading" is defined as sitting down with a book -- print, of course -- and reading it cover to cover. This is how we all traditionally perceive reading, and it's what we're taught reading is from a very early age. There are different types of reading, including close reading (something that is brought up in Corey Ann Haydu's Life By Committee in a way that I think all teens "get": sitting down with a pen and marking reactions, questions, and favorite lines), reading for research (which also includes note taking, whether in the margins or on paper), and skimming/scanning. There are other reading skills taught to us, of course, but those are easily the three biggest ones. All three are taught from early on, and they're taught via the print medium.

The problem is that in today's world, this idea of reading is limiting. It defines reading by the medium in which one type of reading occurs, rather than opening up the idea of reading as an activity one can engage in across multiple platforms, devices, and mediums.

A few years ago when I was working the entire youth services program in my small library, I decided I wanted to shake up how our summer reading program looked. For a long time, the program required readers to track the number of books they read in exchange for rewards along the way. While this is an easy tracking system on the end of the library, it's a very limiting system for readers. Aside from the fact it privileges readers who choose smaller books over larger books and it privileges faster readers over slower ones, it also reinforces the idea of what reading is: a book.

My proposal was that we count time read, rather than books read. After the change was made, when I got into the schools to talk to teens, I asked them specifically what they they thought counted as "reading."

Many thought graphic novels and comics didn't count as reading.

Many thought reading anything on the internet -- blogs, magazine websites, gaming forums -- didn't count as reading.

Many thought picking up a newspaper or magazine in print didn't count as reading.

Many thought that listening to audiobooks didn't count as reading.

When their impressions of "reading" were shared, I told them their perceptions of what counted as reading were very narrow. Why didn't graphic novels or comics count as reading? Was it because those aren't typically what's being read in the classroom? Is it because graphic novels or comics can sometimes have many pages where there's no text? What made a magazine -- either in print or online -- not count as reading?

That summer, I told them I wanted them to count those things as reading. I told them I wanted them to count other things that involved reading to be counted toward reading. Do you spend time reading text messages? Then count it. Do you spend time reading the instructions before you dive into playing a game? Then count it. Do you spend time reading Facebook updates? Then count it. I told them to be reasonable -- count those things no more than half an hour a day -- but that those things absolutely, positively counted as reading.

When summer ended, I saw a marked increase in participation in the reading program, as well an impressive number of hours logged by teen readers. There was nothing inflated and nothing out of the ordinary. Instead, teens saw a redefinition of reading to include the very things they do every single day that require them to be active and engaged readers. You can't respond to your friend's text without reading it, processing it, then forming a response to it. Those are the same skills necessary to engage with a novel or a work of non-fiction assigned in school. The responses may be different. The contexts are different. But all require reading.

Reading is a skill set.

Reading is an activity.

Reading is not a format nor a context.

Of course teens aren't reading like they used to. Of course men aren't reading like they used to. Why would they? The world of reading is wide and vast and it's not limited to one thing anymore.

Before panicking about the numbers and what it is teens or men or women or any other group or category of people are or aren't doing when it comes to reading, or how things were so much better and greater "back in the day," think about how those researchers have defined reading. Think about how we have defined reading for those groups. Are we limiting them to one idea of reading? Or are we allowing them to think about the fact that nearly every single thing they do in today's world -- online and offline -- requires them to engage in reading?

For some more thoughts on this, go read Liz Burn's post "Teens Today! They Don't Read!"

Related StoriesGirls Reading: What Are They Seeing (or Not Seeing)?On Expectations for Girls in YA Fiction, Misleading Reviews, and SexualityWrapping Up "About the Girls"

Related StoriesGirls Reading: What Are They Seeing (or Not Seeing)?On Expectations for Girls in YA Fiction, Misleading Reviews, and SexualityWrapping Up "About the Girls"

First, this survey, done by the Reading Agency, notes that 63% of men feel like they aren't reading as much as they think they should and a full fifth of men admit to saying reading is difficult or they don't enjoy it.

NPR wrote about the findings Common Sense Media had when combing through a series of studies that teens aren't reading like they used to. This one cites a few reasons why this might be, including the rise of tablets and internet-connected devices, as well as the always-present "not enough time" (that's the big reason for the survey above on why men are reading less).

But before we cry about how no one is reading anymore, perhaps we should examine one of the biggest factors not examined in either of these studies: how is "reading" defined?

It appears in both cases that "reading" is defined as sitting down with a book -- print, of course -- and reading it cover to cover. This is how we all traditionally perceive reading, and it's what we're taught reading is from a very early age. There are different types of reading, including close reading (something that is brought up in Corey Ann Haydu's Life By Committee in a way that I think all teens "get": sitting down with a pen and marking reactions, questions, and favorite lines), reading for research (which also includes note taking, whether in the margins or on paper), and skimming/scanning. There are other reading skills taught to us, of course, but those are easily the three biggest ones. All three are taught from early on, and they're taught via the print medium.

The problem is that in today's world, this idea of reading is limiting. It defines reading by the medium in which one type of reading occurs, rather than opening up the idea of reading as an activity one can engage in across multiple platforms, devices, and mediums.

A few years ago when I was working the entire youth services program in my small library, I decided I wanted to shake up how our summer reading program looked. For a long time, the program required readers to track the number of books they read in exchange for rewards along the way. While this is an easy tracking system on the end of the library, it's a very limiting system for readers. Aside from the fact it privileges readers who choose smaller books over larger books and it privileges faster readers over slower ones, it also reinforces the idea of what reading is: a book.

My proposal was that we count time read, rather than books read. After the change was made, when I got into the schools to talk to teens, I asked them specifically what they they thought counted as "reading."

Many thought graphic novels and comics didn't count as reading.

Many thought reading anything on the internet -- blogs, magazine websites, gaming forums -- didn't count as reading.

Many thought picking up a newspaper or magazine in print didn't count as reading.

Many thought that listening to audiobooks didn't count as reading.

When their impressions of "reading" were shared, I told them their perceptions of what counted as reading were very narrow. Why didn't graphic novels or comics count as reading? Was it because those aren't typically what's being read in the classroom? Is it because graphic novels or comics can sometimes have many pages where there's no text? What made a magazine -- either in print or online -- not count as reading?

That summer, I told them I wanted them to count those things as reading. I told them I wanted them to count other things that involved reading to be counted toward reading. Do you spend time reading text messages? Then count it. Do you spend time reading the instructions before you dive into playing a game? Then count it. Do you spend time reading Facebook updates? Then count it. I told them to be reasonable -- count those things no more than half an hour a day -- but that those things absolutely, positively counted as reading.

When summer ended, I saw a marked increase in participation in the reading program, as well an impressive number of hours logged by teen readers. There was nothing inflated and nothing out of the ordinary. Instead, teens saw a redefinition of reading to include the very things they do every single day that require them to be active and engaged readers. You can't respond to your friend's text without reading it, processing it, then forming a response to it. Those are the same skills necessary to engage with a novel or a work of non-fiction assigned in school. The responses may be different. The contexts are different. But all require reading.

Reading is a skill set.

Reading is an activity.

Reading is not a format nor a context.

Of course teens aren't reading like they used to. Of course men aren't reading like they used to. Why would they? The world of reading is wide and vast and it's not limited to one thing anymore.

Before panicking about the numbers and what it is teens or men or women or any other group or category of people are or aren't doing when it comes to reading, or how things were so much better and greater "back in the day," think about how those researchers have defined reading. Think about how we have defined reading for those groups. Are we limiting them to one idea of reading? Or are we allowing them to think about the fact that nearly every single thing they do in today's world -- online and offline -- requires them to engage in reading?

For some more thoughts on this, go read Liz Burn's post "Teens Today! They Don't Read!"

Related StoriesGirls Reading: What Are They Seeing (or Not Seeing)?On Expectations for Girls in YA Fiction, Misleading Reviews, and SexualityWrapping Up "About the Girls"

Related StoriesGirls Reading: What Are They Seeing (or Not Seeing)?On Expectations for Girls in YA Fiction, Misleading Reviews, and SexualityWrapping Up "About the Girls"

Published on May 15, 2014 22:00

May 14, 2014

Free to Fall by Lauren Miller

I didn't expect to like Lauren Miller's

Free to Fall

as much as I did. I went in with some preconceived notions - that it would be very heavy-handed with a message, that it would focus on a romance almost exclusively - and I was very happy to be proven wrong. (But you can forgive me about the romance thing, right? I mean, people talk about "falling" in love...)

I didn't expect to like Lauren Miller's

Free to Fall

as much as I did. I went in with some preconceived notions - that it would be very heavy-handed with a message, that it would focus on a romance almost exclusively - and I was very happy to be proven wrong. (But you can forgive me about the romance thing, right? I mean, people talk about "falling" in love...)What I got instead was a very smart, engaging thriller about a number of things: the pitfalls of technology, the danger of ceding any amount of free will, the nature of trust. It's also a novel very much for teens, covering first love, parental betrayal, and the high school dance. (Did I mention it also has a secret society and some Da Vinci Code-style puzzles? Be still, my heart.)

Here's the basic idea: Rory lives in the near future (the 2030s or thereabouts) where everyone has a handheld (think smartphone, supercharged). Gnosis manufactures the handhelds everyone has, and they also produce an app called Lux which helps users determine the best choice to make in any situation, right down to "What should I order for dinner?" Rory, along with most of her peers, relies on Lux pretty heavily.

Rory has just been accepted to Theden Academy, an elite boarding school for teens which pretty much guarantees her a ticket to a prestigious college and the good life afterward. But Theden has a lot of secrets, and Rory finds herself personally caught up in it. Her mother attended Theden, but left abruptly, then died giving birth to her. She passed along a cryptic message to Rory, telling her father to give it to her when Rory entered Theden.

This book has a lot in it - parents' secret past, a mysterious townie boy, a duplicitous roommate, an evil teacher, strange school tests, Paradise Lost, a secret affair, a secret society, math puzzles, future tech, pop science - and it all leads back to Gnosis and Lux in some way. It's incredibly fun to watch Rory unravel it all. There's never a dull moment. It's a true thriller with a new secret at every turn. I won't say much more since the joy of reading the story is discovering just what Miller throws at you next.

A couple quibbles: some of the foreshadowing is too heavy-handed, and the denouement is too much of a deus ex machina. But I was having so much fun, I didn't care much. This is a near-perfect near-future thriller. It’s twisty, surprising, fast-paced, and very timely. The sketchy boarding school aspect may appeal to fans of The Testing or Variant, the dangerous technology aspect may appeal to fans of Feed, and the sci fi mystery may appeal to fans of Unremembered or Starters (though I think Free to Fall is the smartest of them all). Highly recommended.

Finished copy received from the publisher. Free to Fall is available now.

Related StoriesCress by Marissa MeyerEverything Leads to You by Nina LaCourPlus One by Elizabeth Fama

Related StoriesCress by Marissa MeyerEverything Leads to You by Nina LaCourPlus One by Elizabeth Fama

Published on May 14, 2014 22:00

May 13, 2014

Get Genrefied: Historical Fantasy

I love talking about genre fiction, and I'm really loving exploring all of the many subgenres of fantasy and science fiction in our genre guides each month (though we don't always stick to SFF). This month, we tackle historical fantasy.

I thought I had a pretty good grasp on the definition of historical fantasy, but in doing a bit of searching, I learned that my definition is different from many others' definitions. Hugo winner Jo Walton gives a good overview at tor.com: What is Historical Fantasy? She (and others) use the term to describe any sort of fantasy that takes place in the past or seems like it might take place in the past - whether that past actually existed or not. I take a much narrower view. For me, historical fantasy is strictly fantasy that takes place in a past that actually existed, not just in a world that seems kind of historical-ish.

So there's some disagreement. I prefer the narrower definition mainly because I find the more expanded definition nearly useless. So much of fantasy is pseudo-medieval, meaning we'd call almost all fantasy "historical fantasy" in that case. Moreover, these stories are quite clearly and deliberately not set in our own world. There's no history to be gleaned from stories like that. Part of the appeal of historical fantasy is seeing the ways the author manipulates actual historical events with fantastical elements. I try to be careful in what I call historical fantasy for this reason, and my definition is the definition I'll be using for this guide. (Read a few of the comments in the Jo Walton piece and you'll see I'm not alone!)

Some well-known examples of historical fantasy that fit my definition well are Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrell by Susanna Clarke, The Mists of Avalon by Marion Zimmer Bradley, and Outlander by Diana Gabaldon. On the YA end, Libba Bray's A Great and Terrible Beauty and Robin LaFevers Grave Mercy are good examples.

We've covered awards and resources for fantasy and historical fiction before in our genre guides, so I won't rehash them here. I did find a few interesting reads, though. The first is this piece by Dan Wohl at The Mary Sue: Is "Historical Accuracy" a Good Defense of Patriarchal Societies in Fantasy Fiction? Make sure you read the first comment as well, which points out a serious flaw in his argument, though the point he's getting at is valid. If you're a fan of Game of Thrones (tv series or book series), you've likely read defenses of its treatment of women, one of which probably was "But that's the way women were treated back then!" And here's another reason I prefer my definition of historical fantasy: Game of Thrones is not historical fantasy. The entire world is invented. Martin and the screenwriters made a choice to create cultures like this, and "historical accuracy" is not a legitimate reason.

Even for books that are clearly historical fantasy (or based on history, as GoT ostensibly is), if an author makes a choice to write about dragons and fairies in 17th century England, what's stopping that author from making the society gender-equal? We can suspend our disbelief for dragons, but we can't do the same for gender parity, or even female privilege? Falling back on the myth of historical accuracy demonstrates a supreme lack of creativity. The whole point of historical fantasy is to give the readers a historical time period that is accurate to a point - and then goes off the rails. If it weren't historically inaccurate in some way, it wouldn't be historical fantasy. My point is that the author chose to write the story in that way for a reason, and accuracy ain't it. (I read the Ruins of Ambrai by Melanie Rawn as a teenager, which features a society where women hold all power. It's really great high fantasy; not historical, but could easily be made so. Let's see more of this, yes?)

Anyway.

On the YA front, there are a couple of places that review historical fantasy pretty regularly. TeenReads.com has a page devoted to it, as does Charlotte's Library. Some of the titles mentioned don't adhere to my strict definition, but that's inevitable.

Below are a few recently published historical fantasy titles plus some forthcoming ones. I've restricted the list to books that fit my narrow definition of historical fantasy, otherwise it would be much, much longer. I omitted steampunk since we've covered that already. Descriptions are from Worldcat. What ones have I missed? Let me know in the comments.

The Diviners by Libba Bray

Seventeen-year-old Evie O'Neill is thrilled when she is exiled from small-town Ohio to New York City in 1926, even when a rash of occult-based murders thrusts Evie and her uncle, curator of The Museum of American Folklore, Superstition, and the Occult, into the thick of the investigation.

A Great and Terrible Beauty (and sequels) by Libba Bray

After the suspicious death of her mother in 1895, sixteen-year-old Gemma returns to England, after many years in India, to attend a finishing school where she becomes aware of her magical powers and ability to see into the spirit world.

Bewitching Season (and sequels) by Marissa Doyle

In 1837, as seventeen-year-old twins, Persephone and Penelope, are starting their first London Season they find that their beloved governess, who has taught them everything they know about magic, has disappeared.

Monstrous Beauty by Elizabeth Fama

Tells, in alternating chapters, the story of the mermaid Syrenka's love for Ezra in 1872 that leads to a series of horrific murders, and present-day Hester's encounter with a ghost that reveals her connection to the murders and to Syrenka. (Kimberly's review)

Deception's Princess by Esther M. Friesner

In Iron Age Ireland, Maeve, the fierce, willful youngest daughter of King Eochu of Connacht, is caught in a web of lies after rebelling to avoid fosterage with another highborn family and an arranged marriage.

The Red Necklace by Sally Gardner

In the late eighteenth-century, Sido, the twelve-year-old daughter of a self-indulgent marquis, and Yann, a fourteen-year-old Gypsy orphan raised to perform in a magic show, face a common enemy at the start of the French Revolution.

Chantress (and sequel) by Amy Butler Greenfield

Fifteen-year-old Lucy discovers that she is a chantress who can perform magic by singing, and the only one who can save England from the control of the dangerous Lord Protector

The Faerie Ring by Kiki Hamilton

The year is 1871, and Tiki has been making a home for herself and her family of orphans in a deserted hideaway adjoining Charing Cross Station in central London. They survive by picking pockets. One December night, Tiki steals a ring, and sets off a chain of events that could lead to all-out war with the Fey. For the ring belongs to Queen Victoria, and it binds the rulers of England and the realm of Faerie to peace. With the ring missing, a rebel group of faeries hopes to break the treaty with dark magic and blood--Tiki's blood.

Grave Mercy (and sequels) by Robin LaFevers

In the fifteenth-century kingdom of Brittany, seventeen-year-old Ismae escapes from the brutality of an arranged marriage into the sanctuary of the convent of St. Mortain, where she learns that the god of Death has blessed her with dangerous gifts--and a violent destiny. (Kimberly's review)

Witchfall by Victoria Lamb

In order for magic-wielding Meg to keep the outcast Princess Elizabeth and her secret betrothed, the Spanish priest Alejandro de Castillo, safe in the court of Queen Mary, she needs to make the ultimate sacrifice.

The Falconer by Elizabeth May

In 1844 Edinburgh, eighteen-year-old Lady Aileana Kameron is neither an ordinary debutante, nor a murderess--she is a Falconer, a female warrior born with the gift for hunting and killing the faeries who prey on mankind and who killed her mother. (Kimberly's review)

The Vespertine (and sequels) by Saundra Mitchell

In 1889, when Amelia van den Broek leaves her brother's strict home for the freedom of a social season with cousins in Baltimore, she is surprised by her strong attraction to an unsuitable man, but more so by the dark visions she has each evening which have some believing that she is the cause, not merely the seer, of harm. (Kelly's review)

Dark Mirror (and sequels) by M. J. Putney

When it is discovered that Lady Victoria has magic powers, she is sent away to school at Lackland Abbey, where she joins a group of young mages using their powers to protect England, and travels through time from the early 1800s to the 1940s. (Kelly's review)

The Burning Sky (and sequel) by Sherry Thomas

A young elemental mage named Iaolanthe Seabourne discovers her shocking power and destiny when she is thrown together with a deposed prince to lead a rebellion against a tyrant. (Kimberly's review)

The Fetch by Laura Whitcomb

After 350 years as a Fetch, or death escort, Calder breaks his vows and enters the body of Rasputin, whose spirit causes rebellion in the Land of Lost Souls while Calder struggles to convey Ana and Alexis, orphaned in the Russian Revolution, to Heaven.

In the Shadows by Kiersten White and Jim Di Bartolo

Minnie and Cora, sisters living in a sleepy Maine town in the nineteenth century, are intrigued by Arthur, a mysterious boy with no past who has come to live in their mother's boarding house--but something sinister is stirring and the teens must uncover the truth, and unlock the key to immortality. (Kimberly's review)

In the Shadow of Blackbirds by Cat Winters

In San Diego in 1918, as deadly influenza and World War I take their toll, sixteen-year-old Mary Shelley Black watches desperate mourners flock to séances and spirit photographers for comfort and, despite her scientific leanings, must consider if ghosts are real when her first love, killed in battle, returns. (Kimberly's review)

Dust Girl (and sequels) by Sarah Zettel

On the day in 1935 when her mother vanishes during the worst dust storm ever recorded in Kansas, Callie learns that she is not actually a human being.

Related StoriesA Look at YA Horror in 2014What I'm Reading NowCress by Marissa Meyer

Related StoriesA Look at YA Horror in 2014What I'm Reading NowCress by Marissa Meyer

I thought I had a pretty good grasp on the definition of historical fantasy, but in doing a bit of searching, I learned that my definition is different from many others' definitions. Hugo winner Jo Walton gives a good overview at tor.com: What is Historical Fantasy? She (and others) use the term to describe any sort of fantasy that takes place in the past or seems like it might take place in the past - whether that past actually existed or not. I take a much narrower view. For me, historical fantasy is strictly fantasy that takes place in a past that actually existed, not just in a world that seems kind of historical-ish.

So there's some disagreement. I prefer the narrower definition mainly because I find the more expanded definition nearly useless. So much of fantasy is pseudo-medieval, meaning we'd call almost all fantasy "historical fantasy" in that case. Moreover, these stories are quite clearly and deliberately not set in our own world. There's no history to be gleaned from stories like that. Part of the appeal of historical fantasy is seeing the ways the author manipulates actual historical events with fantastical elements. I try to be careful in what I call historical fantasy for this reason, and my definition is the definition I'll be using for this guide. (Read a few of the comments in the Jo Walton piece and you'll see I'm not alone!)

Some well-known examples of historical fantasy that fit my definition well are Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrell by Susanna Clarke, The Mists of Avalon by Marion Zimmer Bradley, and Outlander by Diana Gabaldon. On the YA end, Libba Bray's A Great and Terrible Beauty and Robin LaFevers Grave Mercy are good examples.