Ed Wagemann's Blog: who will save rock n roll?, page 2

September 25, 2023

the greatest album that never was

There will never be a band as cool as the Velvet Underground. Every hipster worth his weight in analog cameras knows the details: After electric shock therapy as a teenager, Lou Reed drops out of college to pursue the defiant act of writing “sound-alike” recordings for a budget-brand record label in NYC called Pickwick Records. He meets experimental underground Svengali-in-training John Cale at a recording session, sparks fly and Cale soon brings Art/Sound radical Angus McLise into the equation as Reed brings his college buddy Sterling Morrison in. Together they create some noise, but before their first paid gig McLise leaves the band as he admonishes his bandmates for daring to accept cash for a gig (fucking sellouts!). Enter the ambiguously attired computer keypunch operator Moe Tucker on drums (and sometimes garbage can lids). By November of 1965, these scruffians were calling themselves the Velvet Underground (VU) and running in the same circles as Andy Warhol and his Factory of “superstars”. After an orgy of creative gluttony and decadence (okay, I made that part up, but it’s probably true), VU joins forces with Warhol as he injects the husky-voiced German vamp Nico into the mix as part of his multi-media performance art show called the Exploding Plastic Inevitable. This concoction becomes a homage to drugs, sex, attitudes of detachment, with a seemingly total disregard for commercial success… and of course, the fucking music. My god! The fucking music! None of this would have mattered one ounce if it wasn’t for the fucking music.

The fucking music began with the creative implosion between Reed and Cale that resulted in VU’s debut album (released by the MGM subsidiary Verve) The Velvet Underground and Nico. Now regarded as a masterpiece, it was not a commercial success at the time of its initial release, as it sold upwards of only about 60,000 copies during the 1960s. Not terrible for a debut, but when Warhol told Reed that certain changes had to be made for the band to reach that next level of commercial success, Reed totally agreed and promptly fired Warhol. Nico quit shortly afterward and the VU then recorded its least commercial album in its catalog, White Light/White Heat. White Light/White Heat has John Cale’s dissonant experimental, outlandish vibe all over it. But as Cale pushed the band further toward an experimental direction (he wanted to actually record music underwater) Reed fired him — despite the protestations of Morrison and Tucker. Within a few days, Reed picked up teenage, multi-instrumentalist/vocalist (and Reed look-a-like) Doug Yule. With this new line-up, the VU signed with Verve’s parent company MGM for a two-record deal. The first album of the deal, recorded in 1969, was the self-titled masterpiece The Velvet Underground (sometimes referred to as the gray album) — a soft, soulful album that explores the psychological and spiritual journey of a young hipster’s bisexual awakening. Strangely enough, this album did not end up as a blockbuster.

Which brings us to the greatest album that never was. At first, everything seemed set up and ready to go for the Velvet Underground’s next record. MGM reserved a catalog number for the next VU album and on May 6th of 1969, VU entered the Record Plant in New York to begin recording. By June, half the album was recorded and VU set out for their summer touring schedule. This tour gave them the chance to polish the remaining songs that would make up this next album and when they returned to the studio in September they were really smoking baby! By October they finished an acetate from their recording sessions. By November the band was discussing album titles. But then… then… nothing. The recordings for this fourth album were inexplicably shelved. They stayed forgotten and rotting away as they remained unreleased for the next 16 years. So… what was the deal? What happened? How did this mysterious, amazing masterpiece end up as a ghost for 16 years?

The most obvious answer would begin with Steve Sesnick (VU manager at the time) and Mike Curb (president of MGM/Verve at the time).

Sesnick, a former St. John’s college basketball player, had become the manager of the legendary Boston nightclub, The Boston Tea Party by the time he was 25 years old. Less than two years later, he took over duties as VU’s manager when Andy Warhol was fired. Sesnick negotiated a two-record deal between VU and MGM in 1968, but pointed out that the band was not happy with how MGM had dropped the ball on distributing their first two albums — he specifically cited examples of how difficult it was to find copies of Velvet Underground albums in record stores wherever they toured. MGM made promises to do better, but by the time VU finished its third album, MGM had undergone a change. As they merged Sidewalk Records into their fold and named Sidewalk’s 24-year-old founder Mike Curb as president for both MGM and Verve Records, the label all but forgot about the VU. Distribution of their third album was a barren desert. Tumbleweeds. Mike Curb was apparently busy losing $17 million that year for MGM. The company ended up firing 80 recording artists and 250 staff workers. By the time the Velvet Underground was finishing up recording their album in late 1969, Sesnick was clearly beginning to see the light. So he began talking with Atlantic Records in negotiation for VU’s next record deal. In the meantime, he urged VU to finish this fourth album so they could end their contract with MGM. Which is what Reed and company did. They finished their fourth, soon to be lost, album.

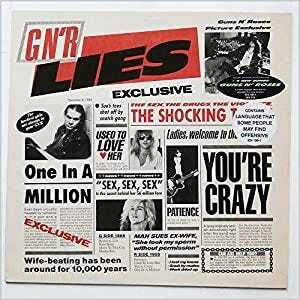

The new head of MGM, Georgia-born Mike Curb was not just the president of MGM, he was also the leader of the squeaky clean contemporary adult pop group, The Mike Curb Congregation, and as president of MGM he was signing other similar squeaky clean acts like the Osmond Family and Christian pop acts like Larry Norman and Debbie Boone. Just take a look at a photo of the Velvet Underground next to a photo of the Osmond Family. Would anyone in their right mind think that these two acts belong on the same label??? With drug songs like “Heroin,” “I’m Waiting for My Man” and “White Light/White Heat,” Curb obviously didn’t think so, and in late 1970 he declared in a public statement that MGM “Will not knowingly release any records that advocate the use of drugs or glamorize their usage.” This announcement prompted Eric Burton, formerly of the Animals and War, to publicly declare that he was a drug user and therefore should be immediately dropped from MGM as well.

The bottom line was that as soon as Curb took the reigns in 1969, he was not going to let MGM release, let alone promote, any Velvet Underground record. That meant that not only did he put the previous VU albums in mothballs, but he vehemently refused to let their fourth album see the light of day. Unfortunately, Sesnick didn’t realize this until after VU had already recorded their fourth album — the lost masterpiece that the world would have to wait 16 years to get a listen to. Although this was obviously a major crime against Rock music (some would claim against all humanity), it was indeed a very advantageous springboard for Curb’s political career as Curb began to be regularly cited as a hero of the Nixon Administration for this hard-line, anti-drug stance. In January of 1973 in fact, Curb was named chairman for the Inaugural Youth Concert for President Nixon. Republican Governor of California, Ronald Reagan, also encouraged Curb to enter politics. Reagan backed Curb as he ran for and won California’s Lieutenant Governor election in 1978 (the last Republican to serve as Lt. Governor of California). Curb also served as the National Chairman for Reagan’s successful 1980 Presidential campaign.

As for VU, they signed the deal with Atlantic Records and released two more studio albums, the beautiful pop-centric Loaded and the VINO (Velvet In Name Only) Doug Yule-led stinkaroo, Squeeze. But Lou Reed had already been so fed up with the record industry’s bull shit by the time they finished Loaded that he quit the band, moped off to live in his parent’s basement, and became an accountant (at least for a while). And the lost 4th album, the masterpiece that could have changed the direction of Rock history and ushered in Punk/New Wave/Indie Rock/College Rock a full decade ahead of schedule, sat wasting away in the crickety vaults of some corporate storage unit just collecting dust as the years drifted away. It’s so cold in Alaska.

[image error]September 18, 2023

the day i discovered iggy pop

There should come a time in every teenager’s life when nothing makes sense anymore. The things that you held as truths in your youth should be exposed as bull shit. It’s a short leap from realizing Santa is make-believe to realizing God is make-believe to realizing all of society is full of shit. You should realize the preacher is full of shit, the tv newsman is full of shit, the politicians are all full of shit, your teachers are full of shit and even your parents are full of shit. And all the sudden this entire life that we humans are living on this planet shouldn’t make any fucking sense anymore. What have we been doing all this time? Nothing has a purpose. And by 1984, that is exactly where I was, but to compound all of that, Rock was dead as well. Rock music had sold out. It had gone Mtv on my ass.

So, I wandered aimlessly through my high school days (daze) like a plastic bag floating aimlessly along the expressway. I stayed up late watching TV all night and then slept during my classes all day. Days passed, weeks, maybe months… Then one night, there it was: on Cinemax, a teen movie called Repoman. I didn’t even actually watch the movie all the way through — it was horrid — but the music caught me off guard… the music shocked my ass back to life. This was the first time in weeks, months — maybe even years, that I had this feeling that maybe Rock wasn’t really dead after all. Maybe it had just been hiding or hibernating somewhere underground.

The title track from this movie in particular, just simply kicked my dick off. It was by some guy I had vaguely heard of, some guy named Iggy Pop. Sonically, lyrically, and in every other way, the song “Repoman” perfectly summed up what life was like for me at that moment.

It started off with two drumsticks smacking together calling a meeting of some sort to order. Then, immediately interrupting the senses, is a frantic, escalating minute-long guitar intro by former Sex Pistol Steve Jones. As this guitar freak-out grabs you, you almost don’t notice the rhythm section — which happens to be the rhythm section from Blondie in bass player Nigel Harrison and drummer Clem Burke. Burke’s work is especially inspired as, throughout the song, he haphazardly and sporadically throws in this clanking sound of a far-off but impending anvil, as if it is coming from inside a smoky steel mill. Also he mixes the crashing sounds of a car wreck throughout the song here and there. Then, after being introduced to the rhythm section, just as you are realizing this is going to be a crazy ass burner of a ride — something akin to getting the shit beat out of you by a gang of bullies who show no signs of letting up — in comes this raw, frenetic deep baritone voice with:

I was riding on a concrete slab

Down the river of a useless flab (land),

it was such a beautiful day,

I heard a witch doctor Say,

“I’ll turn you into a toadstool”

Da fuck is this?!?

It’s Iggy Fucking Pop, that’s what da fuck this is!

And with that opening stanza, I’m smacked with a bolt of lightning. I sat there on the living room sofa, just wide-eyed and slack jawed. What else could I do? For what better metaphor for the state of total disillusionment and disenfranchisement of America during the 80s could there be than this? Immediately I recognized Reagan in the line about the “witch doctor” spewing his voodoo economics. And the “useless flab” was America, or else it was the flab of skin that hung from Reagan’s neck — one or the other, I wasn’t sure, but either way, it was the perfect metaphor. Then “Riding on a concrete slab down the river” connoted corporate corruption and pollution and an obvious reference to Reagan’s massive corporate deregulation that was running rampant and allowing corporate plants and factories to pollute our air, water and land… Reagan was turning our beautiful American land into a toadstool (a poisonous fungus… toadstool disease) and Iggy Pop was calling him out for it!

From there, the lyrics spewed out like prophecy. Not understanding all of the words or meanings at first, I had to catch words and phrases in bits and pieces like a “sermonette, a TV cook” and “divinity throws you a curve” as I realized that Iggy was depicting a portrait of America in the mid-1980s as if he was an updated Nelson Algren.

Iggy was describing the two extremes of people who called themselves Americans. In a single phrase he was describing both the disillusioned mainstream Americans who fist-pumped the flag of the country with God on our side, the land that was founded on freedom of religion, those who “Amen-ed” the Right-wing televangelists that dominated the late-night TV screens and who worshipped our corporations, while at the same time Iggy was describing the lost, frustrated Americans, the “alcoholic at the bar” in which “every insult goes too far” and their disenfranchisement with our corporate government, a disenfranchisement that began with the Vietnam War — the war in which America completely lost its “moral” superiority in the world, that moment in history where it should have been obvious to an entire generation that the United States was no longer a country with God on our side. We’d been hood-winked folks and now we were all left “looking for the joke with a microscope”.

Iggy rages on and comes to the furious stanza that begins “I was pissing on the desert sands”. Desert sands is a reference to America’s involvement in the Middle East and the oil crisis that the country was in the midst of as corporate oil companies sought to increasingly pollute our environment (as well as the minds of the American people). Further evidence of this comes from the wistful lines “Things will never be the same” which sadly announces that the American dream is dead. And then the line “I run this gas and oasis” which further pounds the references to corporate oil company control even deeper. But beyond blaming the politicians and the clergy and the corporations, Iggy casts his last accusation to the people who allowed this to happen as he makes a sharp turn and points his arrow directly at himself — who is also myself, and every washed-out dude in America — and he perfectly encapsulates our entire existence, our entire point of view, our entire mind frame when he sings “I was a teenage dinosaur”…” using my head as an ashtray.” My sentiments exactly Mr. Pop. Egg-zactly! We may be pawns in the game, but who’s fault is that?

Okay then, so what now? Now that we’ve admitted all this bull shit and we’ve copped to our involvement in it, what can we do? What can any of us do? Toward the end of the song, if you have somehow survived this sonic and lyrical onslaught into its last stanza, Iggy proposes his resolve to all this bull shit. In brilliant ambiguity, Iggy proclaims that now he is the Repoman — and that he is now the one looking for the joke with a microscope as well. And it is this line that I am left pondering as the song dissolves into dissonant, nightmarish guitar licks wrapped in echoes.

Wait. What?

There were a few ways to interpret this ending. There was the glass is half empty interpretation or the glass is half full interpretation. Think about what a Repoman does. He repossesses something that someone has bought (or bought into)… something that someone can’t actually afford. So, is Iggy being critical of the Baby Boomers who have bought into this corporate way of existence for America? Is he expressing that these old fucks are a lost cause and now it is time for the youth of America to take back or “repossess” our country? Is it up to us to take back the old weird, American way? Or… or is he just saying it’s all a lost cause and let’s just ride it out for whatever worth it has left — then junk it? Like Slim Pickens riding the H-bomb into oblivion in Dr. Strangelove, we might as well whoop up some hell on our way out. Either way, no matter what ending you prefer, this song perfectly depicts the attitude and atmosphere of Reagan’s America in the 1980s.

The RepoMan song and the RepoMan soundtrack also served as my introduction to early 80s hardcore punk, as it did for millions of other middle Americans. 1984 was the year that signaled hardcore’s peak and its demise. My hardcore phase barely lasted a year as I transitioned to my prolonged college rock phase by 1985. There would be many bands that would try to emulate Iggy’s rage against the machine, but none would come close to having the impact and perfect poetic encapsulation that RepoMan did. It was a last sad, cry for help from the dying old weird America.

[image error]September 15, 2023

One Album Wonders (of the 20th Century)

One Album Wonders (of the 20th Century)

ONE ALBUM WONDERS (OF THE 20TH CENTURY)

[image error]

[image error]

September 4, 2023

Lennon vs Reagan in the battle for America’s soul

March 30, 1981. There it was: news footage of newly elected President Ronald Reagan walking toward his limousine, waving toward a crowd when suddenly gunshots erupted in a cacophony. Two dozen Secret Service agents and law officers jump into action, shielding and shoving Reagan inside his awaiting limo. Reagan disappears, and within minutes the video footage appears on television sets around the country.

To millions of Americans, it rekindled memories of the assassinations of Robert Kennedy and John F. Kennedy — but I immediately thought of John Lennon. Lennon had been shot to death just weeks prior. A deranged assassin pulled out a revolver outside Lennon’s longtime residence, the Dakota building in New York City, then shot Lennon several times in the back. Likewise, Reagan was shot at close range with a revolver, not too far from his home. Also like Lennon, Reagan was immediately rushed to the nearest hospital where his visibly shaken wife demanded to be at his side. The difference of course is that Lennon’s wife, the conceptual artist Yoko Ono, watched blood gurgle from Lennon as he took his last choking breaths before dying, while Reagan’s wife Nancy, a former Hollywood actress, watched Reagan recover and survive. It was later reported that if Reagan’s would-be assassin’s bullet had hit just a half inch closer to Reagan’s heart, then Reagan would have been killed as well.

I was still a few months shy of my 13th birthday at the time. All I really cared about in life was sports, mostly football. My afternoons consisted of hours and hours of football. Epic battles ensued as all of my neighborhood friends and all my neighborhood enemies divided into two teams and then bashed each other around a meadow on the edge of town each day after school. At sunset I’d bicycle home, my body riddled with bumps and bruises, my shirt ripped and my pants grass-stained. A highlight reel of that day’s game played inside my head until, by nightfall, these images were replaced by heroic fantasies of making future tackles and brilliant catches. But my obsession with football was rudely interrupted on the night Lennon was murdered. It was a Monday night and I was up late watching an NFL game between the Patriots and Dolphins when, in the closing moments of regulation, famed sports announcer Howard Cosell paused the play-by-play to announce that John Lennon, the most famous of the Beatles, had just been shot. I sat there bewildered. My mother was washing dishes in the kitchen while my younger brother was already asleep on the couch. Cosell’s words seemed like about the strangest thing I had ever heard during a football game. The shooting of a musician… Why was this being reported during a football game? As the Patriot’s placekicker set up for the potential game-winning field goal, my attention left the game entirely. “Why in the world would someone kill a musician? Especially a Beatle?” I wondered…

I didn’t consider myself a Beatles fan at that age, but like most American households, John Lennon’s music (especially with the Beatles) was a regular presence in my life as I grew up during the 1970s. For the next couple of days after Lennon’s death, I noticed my mom and other grownups visibly disturbed by the tragedy. It was just seventeen years earlier that Lennon first burst into the American consciousness. As the leader of the Beatles, his voice sang out from American radio sets just days after our nation witnessed one of our greatest national tragedies — the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. Kennedy had been gunned down in broad daylight on the streets of Dallas, Texas. The assassination of JFK hit America hard. America’s golden age, a period of more than a decade of post-WWII afterglow, was suddenly sacked. The entire nation went into a state of mourning, shock and sorrow. Americans were in desperate need of something to help them recover, something to make them feel good again, something to allow them to laugh again and to dance again and enjoy life again. And right then, at that very moment, here came the Beatles, and Beatlemania exploded across the United States in a phenomenon never seen before or since. Lennon and company invaded the national media and took over entire cities with their sold-out live performances. They sold more vinyl records than anyone else in history. Their images were plastered across every magazine and newspaper in the land. They starred in top-grossing critically-acclaimed films, had a popular animated series on TV, made historical TV appearances and, during the week of April 4, 1964, they achieved the unheard-of feat of having all 5 of the top 5 spots on the weekly Billboard Hot 100 pop music chart. The Beatles were bigger than Jesus. It seemed like they had rescued America.

Seventeen years later though, it would be Lennon’s assassination that sent Americans into mourning. Upon hearing of Lennon’s murder, crowds of New Yorkers gathered outside the Dakota building. Within minutes there were thousands. Eventually, this crowd was herded into New York’s Central Park. The outpouring of grief swept across the nation, the globe. The media covered Lennon’s assassination in as much detail and intensity as if it was the assassination of a world leader. To many Lennon was more influential than John Kennedy, Robert Kennedy, or Martin Luther King Jr. His reach was global, ageless, emotional, personal. In response to his death, millions of people from all corners of the planet paused for ten minutes of silence to remember Lennon. Every radio station in New York City went silent for those ten minutes. Extreme Beatles fans went as far as committing suicide. Millions wept.

Reagan was sworn into office just a month afterward, and similar to how Lennon and the Beatles had helped America heal from the death of John Kennedy 17 years earlier, it was now President Reagan whom Baby Boomers would look upon to help them heal. Not just from the assassination of Lennon, but from a decade that seemed to be mired in one crisis after another: the 1970s. Although I was sheltered in an idyllic Midwest small-town during the 1970s, the decade was a low point for America that compared to the Great Depression and the Reconstruction. To paraphrase President Jimmy Carter, it was an “Era of Malaise”. Americans of the “Era of Malaise” were the first Americans in history to witness America losing a war (Vietnam). Their TV sets brought them horrific images of U.S. soldiers committing unspeakable atrocities on innocent women and children on a nightly basis. There were ghastly, real-life testimonies of soldiers raping young Vietnamese girls then savagely beating and killing them in front of their parents and siblings. The magazines and newspapers were filled with confessions and details about innocent children being burnt in their village huts. If this wasn’t enough to cause havoc on the American conscience during the Malaise Era, there was also the Watergate scandal, a televised live-action national tragedy that put the very validity of our nation’s government in doubt. America’s very soul was in question, and the confusion was compounded further as, after 25 years of economic prosperity and expansion, America’s economy was suddenly in turmoil. The economy was so unstable that new terms had to be invented to describe it — terms like “stagflation” and “the misery index”. On top of that, the disintegration of the American nuclear family was unfolding before our citizen’s eyes. All the pillars of American culture that Americans had grown up believing in — God, country and family — were suddenly crumbling. The assassinations, turmoil and civil rights activism of the 1960s had ushered in the “culture wars” of the 1970s — which not only pitted father against son, but father against mother, mother against daughter, and daughter against son. The divorce rate doubled in America every single year from 1965 to 1975. The Pill was suddenly available. Abortion was legalized. Gays were not only coming out of the closet but demanding attention and equal rights. Blacks were forcing controversial affirmative action laws upon legislatures. Women were burning their bras and speaking up for equal rights. There was wife-swapping and disco music. The Malaise Era Americans witnessed the happy, hippy recreational drug use of the 1960s give way to frequent overdoses of drug addicts and street punks. Crime was running rampant, hitting all-time highs as urban areas were experiencing white flight and cities were going bankrupt. The headlines were full of hi-jackings, kidnappings, bombings, and cult abductions. By the time Jimmy Carter made his infamous “malaise” speech in 1979, the average American was not just in a fog of malaise, but they were exhausted, out of work, resentful, and suspicious of their government. They were confused about the present, afraid of the future and without any hope for tomorrow. And then, right on cue, as if scripted from a Hollywood screenplay, with his easy smile and down-home charm, in rides the tall, handsome hero on his white horse to save the day, to give our nation the sure-footed direction that it so badly needed. Ronald Reagan was here to give hope of bringing America back to simpler more wholesome times.

That was the promise at least. Reagan, who had a good-natured, optimistic singing cowboy vibe about him, campaigned on the idea of making America Great Again — and Americans thirstily bought into it. They were tired of being malaised. And, as if to demonstrate just how great America was, Reagan’s first order of business was to preside over an inauguration that proved to be an exercise in extravagance. The celebration of wealth and privilege that Washington DC put on display the day of Reagan’s inauguration was the likes of which had never been witnessed before. Corporate jets lined up wing to wing on the tarmac at the National Airport in DC as America’s wealthiest citizens poured into the city. So many millionaires flooded into DC that the nation’s capital ran out of available limousines and had to import fleets from as far as Atlanta, Georgia. Fur coats, diamond jewelry, and designer dresses were on display everywhere you looked. Banquets overflowing with gourmet food by world-famous chefs cramped every hotel and fine establishment in the city. By the end of the evening well over a million hors d’oeuvres were catered to the thousands of corporate sponsors that now occupied the nation’s capital. Nancy Reagan, the new first lady wore an outfit that cost over $25,000 (enough to feed 50 welfare recipients for an entire year, as one newspaperman reported). Nancy Reagan also insisted on having several hair stylists on call that night, waiting in the helicopters that flew her from one inauguration party to the next. The “haves” were ready to celebrate, and if John Lennon were still alive he might have seen fit to reprise his famous quote, “…Will the people in the cheaper seats clap your hands? And for the rest of you, if you’ll just rattle your jewelry…”

A couple of weeks later, when the news footage of Reagan being shot at close range was being played over and over by TV stations, I was still thinking about John Lennon. It’s strange that, just as Lennon’s entry into American lore was forever linked to JFK’s assassination, now his demise was linked to the assassination attempt on Reagan — at least in my mind anyway. On the very day Reagan was shot, headlines of Lennon and his murder were still gracing the covers of magazines and newspapers. And the juxtaposition of these story headlines sent my 13-year-old brain reeling on a chase to link these two men together. The obvious, most tangible link between Reagan and Lennon largely hinged on the fact that it was hard to imagine two human beings of such iconic stature who better represented the polar opposite sides of the monumental cultural tug-of-war that had been fought in the United States of the 1960s and 1970s. This cultural war, where the ultra-conservative, buttoned-down, aging establishment was suddenly challenged by the free-loving, dope-smoking, radical hippy youth, defined not only America in the 60s, but it would define the central cultural evolution of America over the next two decades as well. The culture war changed America to such a degree that by the time of Lennon’s assassination, the things that Americans had only been able to whisper about in back rooms prior to the invasion of the Beatles — subjects like race, religion, war and sex — were now being confronted out loud at dinner tables, and out on the streets, and in the movies and on the TV sets of America. Lennon was a touchstone for this change that had taken place in America — from his remarks about the Beatles being bigger than Jesus to his historical TV appearances on the Dick Cavett Show and the Michael Douglas Show. And plenty of folks couldn’t help but wonder if the motive behind Lennon’s assassination had something to do with all that. Had this change in American values so deeply enraged the core of conservative America that the only way to strike back was by putting an end to the life of the man who had been such a focal point for so much of that change?

For several weeks after Reagan’s shooting, I was hungry for all the news and information about the two shootings I could get. As the stories of the two assassination attempts unfolded it was revealed that the man who shot Lennon — a young drifter named Mark David Chapman — was obsessed with the idea of celebrity. Chapman had been a fan of the Beatles but had become disillusioned by some of (what he perceived as) Lennon’s anti-Christian comments and lyrics, both with the Beatles and then during Lennon’s solo career. Still though, in the final days leading up to the shooting, Chapman loitered around the Dakota Building, giddy with the idea of possibly seeing Lennon in person. On the actual day of the shooting, Chapman even asked Lennon for an autograph. Interestingly enough, as the story of Reagan’s shooting came out, it was revealed that the young man who shot Reagan, John Hinkley Jr. had a similar fascination with celebrity. While Chapman seemed to believe that the Beatles and J.D. Salinger (author of The Catcher in the Rye) were sending him signals via their creative works, Hinkley believed that the actress Jodi Foster was sending him messages through her work on the movie screen.

The similarities between Hinkley and Chapman did not end there. Looking at photos of Hinkley and Chapman from that time, there is a striking physical resemblance between the two. In fact, they looked as if they could have been twin brothers. Both young men were 25 years old — both were born in May of 1955. Both grew up in Texas and they both embarked on adulthoods that consisted largely of drifting from place to place. Hinkley dropped out of college in 1975 and moved to Hollywood to become a songwriter. Similarly, Chapman worked as a musician who played guitar at churches and nightspots throughout the 1970s. But the most intriguing connection between the two was that both had close, long-term ties to World Vision — an international religious organization that had allegedly been a “front” for the CIA. Chapman had been a key aid to the program director at World Vision. His position led to meetings with the 38th President Gerald Ford as well as other top government officials. Hinkley’s connection to World Vision was just as prominent: the president of World Vision was his very own father, John Hinkley Sr.

This World Vision connection seemed like too much of a coincidence, even to my 13-year-old brain. And in fact, over the years it prompted conspiracy theory talk centered around the CIA’s mind control program (dubbed Project MKUltra). The existence of MKUltra had been mistakenly revealed to the public three years prior to Lennon’s assassination thanks to a FOIA (Freedom of Information Act) request. Initially, MKUltra was only alluded to in the wake of Congressional investigations of Watergate by the Church Committee and the Presidential Commission (aka the Rockefeller Commission) that investigated illegal activity conducted by the military and Intelligence agencies. Most of the information regarding MKUltra was systematically destroyed by Richard Nixon’s CIA director (Richard Helms) during the Watergate panic in 1973, but enough documentation survived to reveal that the U.S. government had indeed used LSD and hypnosis in an effort to brainwash unwitting citizens into become assassins. World Vision was suspected as one of the ‘fronts’ the CIA used to recruit and employ these assassins. So its not surprising that the fact that Hinkley and Chapman had such close ties to World Vision led conspiracy theorist to believe the Lennon and Reagan assassination attempts had been government sponsored.

As strange as all of that seems, I didn’t pay much attention to conspiracy theories. Why would the government want Lennon or Reagan dead? And honestly, at 13 years of age, I didn’t even really know what the CIA was exactly. Still though, with each bit of information I came across, the deeper I found myself drawn into the Lennon-Reagan connection. I became a fixture at my local library, digging up past newspaper accounts and magazine articles on anything dealing with Reagan or Lennon. And with each bit of information I found, the more the Lennon-Reagan shootings became intertwined in my mind until an obvious narrative emerged — a narrative that centered around the ideological battle between Reagan and Lennon. It was a head-to-head ideological fight that first erupted drastically in 1969 when LSD guru Timothy Leary asked John Lennon to write the slogan song for his campaign to unseat Reagan, who was then the Governor of California. Leary asked Lennon to write the song around his campaign slogan “Come Together”. Lennon obliged, and when “Come Together” was released months later it immediately became an anthem for the Baby Boomer generation. Reagan’s reaction to Leary and Lennon’s challenge was swift. In 1966 Reagan had centered his campaign around the platform of cleansing California of the epidemic of stoned hippies that were taking over his state. In fact, Reagan was instrumental in getting California to outlaw LSD. So now, challenged by Leary, Reagan encouraged criminal prosecution of Leary for an earlier possession of a marijuana charge. Leary was found guilty and sentenced to 20 years in prison. Instead of serving his time, Leary fled the country, becoming a fugitive, thus Leary’s attempt to unseat Reagan was unsuccessful. Reagan remained in office.

But remaining in office as the Governor of California wasn’t Reagan’s end goal. Reagan had his sights set higher and in 1968 he made his first run for the Presidency of the United States. Although he was soundly beaten by Richard Nixon for the Republican nomination, the defeat caused Reagan to realize his weakness: He simply wasn’t considered to be a heavy weight on the national level like Nixon was. But there was something Ronald Reagan had in common with John Lennon: he understood the potential power of the burgeoning American mainstream mass media. Reagan played football in college, then he was a sports announcer, then a B-movie actor, and was now an avid NFL watcher. He understood the AMerican fascination with the ‘big game’, the ‘big play’, the ‘big hero’. And then one night, just a week prior to Richard Nixon being sworn in as the 37th President of the United States, an idea came to him. Reagan was watching a football game, Superbowl III no less. He had been wrestling with ideas on how to become a national political figure when, like the rest of America, Super Bowl III captured Reagan’s imagination as he was swept up in the big-time showdown. Superbowl III was the first time the moniker ‘Superbowl’ was actually used for the National Football League’s championship game. And it was the first time Roman numerals were used (similar to the way they were used to denote WWI and WWII). The game was further elevated to national status because it pitted a brash, long-haired rebel Quarterback named Joe Namath against, Conservative Christian, military haircut-wearing All-American Johnny Unitas. With unprecedented media hype, this wasn’t just a football game, it was a cultural showdown. Broadway Joe Namath, who boldly claimed his underdog New York Jets would defeat the mighty Indianapolis Colts, was catapulted to the status of a national household name right in front of the nation’s (and Reagan’s) eyes as he led his Jets to an amazing upset victory.

John Lennon’s friend Bob Dylan once sang, “You know there’s something happening, but you don’t know what it is, do you, Mr. Jones?” The lyric couldn’t have been more appropriate on that night, as Nameth led the Jets to one of the most miraculous upsets in pro football history. Conservative America sat and watched in stunned horror as a tidal wave of publicity rode Namath into the stratosphere of folk hero stardom. Reagan however, immediately understood what was going on. As Namath became the most popular human being in America, Reagan was starting to flesh out a drastic plan that would put him in the national spotlight as well. A plan that would place him on the Presidential level that Nixon was on. He needed to create a showdown. He needed to choreograph a media event where he could back up his tough talk about combatting the hippies with strong, decisive action. Reagan’s tough talk during his previous campaign had targeted the drugged up hippies that were trying to overtake not only his state, but the entire nation. Just like Namath had promised he would take care of the Colts, Reagan boldly took to the stump promising that he would take care of the hippies. Reagan’s anti-hippy rhetoric moved enough Californian voters to the polls to propel him to the governorship of California in the previous election. But the hippies had run even more rampant since he took office. Now Reagan embarked on a series of tough justice speeches in a campaign of showy, hyped-up, political gatherings. He made promises of cleansing the state of the hippy protesters like those at UC Berkley and other colleges. Reagan had taken out Leary, a symbolic victory, but that was just one man. Reagan’s scope was much greater now. He ramped up his rhetoric, going as far as declaring that Berkeley students and administrators had turned the campus into “a haven for communist sympathizers, protesters, and sex deviants.” Now it was time to do something about it.

After watching Namath back up his words by defeating the Colts, Reagan realized that if he could back up his bold words with a bold, tangible defeat of the hippies then it could create a sensational media event and propel him to the national spotlight in full Joe Namath fashion. And ironically, football would provide the catalyst for the event he needed. On April 28, 1969, the University of California at Berkeley released its plans for building a football field on a site called the People’s Park. This announcement caused an immediate conflict because a group of free-wheeling hippy locals had already organized and built a public park on that land. These hippies used the park for free speech rallies, full of “peace and love and beads and other funny smelling cigarette-type of stuff”. The hippies had acted without the approval of University officials and since the land was private property, Reagan was going to have none of it. Reagan ordered thousands of police, including the California Highway Patrol, into the area to break up the massive ‘sit-ins” the hippies organized. When that didn’t work, his opportunity to create a national media event fell into place. Reagan called in the National Guardand then the blood flowed.

John Lennon and his soon-to-be wife Yoko Ono, taking a page right out of Broadway Joe’s playbook himself, were creating a media storm of their own. Their media campaign began one eventful night in London as they both appeared inside of large brown paper bags at an underground artist’s gathering called the Alchemical Wedding. Later, in a press conference in Vienna, just weeks after Superbowl III, Lennon described what he was doing. He called it “bagism” saying that he and Yoko sat in the bags to challenge audiences to be participants rather than passive consumers. “Yoko and I are quite willing to be the world’s clowns; if by doing it we do some good,” Lennon said. From there, Lennon and Ono jump-started a campaign of headline-grabbing media stunts the likes of which the press had never witnessed before. In April of 1969, John and Yoko sent acorns to the heads of state in over 80 countries around the world, with instructions that these world leaders should plant the acorns as a symbol of peace. This was after they used the occasion of their March wedding to hold a week-long “bed-in” to promote world peace and to protest war. Two months later they tested the ‘bed-in’ waters again by holding another one, this time just north of the American border in Montreal, Canada.

The bed-ins were derived from the non-violent “sit-ins” that were the most popular form of civil disobedience with the students and staff at UC Berkeley whom Reagan was at war with. These kinds of protest groups would sit on college campuses or in front of civic buildings or private property until the police came and carted them off. It was a surefire way to get media attention and Lennon’s bed-in in Montreal magnified that to the international level. During the bed-in, celebrity guests ranging from Tommy Smothers to Timothy Leary dropped in to participate in the recording of Lennon’s “Give Peace a Chance”. The bed-ins attracted a throng of tabloid newspaper people and media attention. One staunch Conservative cartoonist named Al Capp barged into the bed-in looking to start a fight. Capp began to verbally spar with Lennon, who was casually lying in bed with signs like “Hair Peace” displayed behind him. A surreal scene quickly ignited into a full-blown insult-fueled confrontation as Lennon brought up the subject of the student protesters at the University of California Berkley. This was just days after students and faculty at UC Berkley had been shot and killed as Reagan interrupted their peaceful protest by ordering the California National Guardto descend upon them. The bloodbath, “Bloody Thursday” as it became known, became the national media sensation that vaulted Reagan into the national spotlight. Both Reagan and Lennon were in the national spotlight now, on the opposite side of the issues. Both had engineered their massive media events designed to advance their opposing ideologies. Lennon had captured the media’s imagination with his wild antics. Reagan had promised a bloodbath and then delivered. Al Capp might not have understood what was going on, as he and other Conservatives in the media scoffed at Lennon and Ono’s media assaults, but Lennon and Reagan understood exactly how a sensationalistic media event could further an agenda and galvanize lofty ideas into a forced effort.

Al Capp badgering Lennon

Al Capp badgering LennonBefore and after Governor Reagan ordered the California Highway Patrol and then the Californian National Guard to quell the protests at UC Berkeley that resulted in “Bloody Thursday” he spoke to the press, sounding like a football coach cast in a Hollywood B-movie. He recited lines such as, “If it takes a bloodbath, let’s get it over with.” His words couldn’t have been more at odds with the words that Lennon was putting forth, “Give Peace a chance” and “Love is the Answer”. As Bloody Thursday battled Lennon’s “bed-ins” for national headlines, Lennon and Ono moved on with their plans for an international multimedia campaign. This included renting billboard space in 12 major cities around the world that declared “WAR IS OVER! If You Want It — Happy Christmas from John & Yoko”. Some media outlets reported these as publicity stunts while others treated them as cultural events. Nearly all of the media reported Bloody Thursday as a historic culture clash instead of merely a publicity stunt.

But the greatest live media event involving Reagan would of course be the assassination attempt on his life and his recovery from it in early 1981. It wasn’t scripted, but as I watched Reagan recover from his gun wounds that spring and witnessed how he glibly (or heroically, depending on how you saw it) spouted off one-liners to reporters, it was obvious that Reagan was prepared for this role. The nation was fascinated with Reagan’s survival and speedy recovery and this moment would become one of the centerpieces of every biography written of him ever after. It was the turning point. Unlike Lennon’s assassination, which marked the end of an era — the unhappy ending of the hippy dream — Reagan’s survival symbolized the exact opposite. It proved that his Conservative American dream was inevitable. Even bullets couldn’t stop it. It was as if Johnny Unitas had limped off the bench in the final seconds of the 4th quarter and thrown a long touchdown pass to win the game and defeat the long hairs once and for all. And with the unprecedented popularity that Reagan received after surviving the assassination attempt, it was carte blanche for his conservative agenda. It transferred the political capital to him that was needed to increase the defense budget to astronomical heights while simultaneously cutting spending on food stamps, healthcare for the poor, federal education programs, and the EPA. His administration attempted to purge as many people with disabilities as possible from the Social Security disability rolls and cut food programs for school kids. Watching all of this unfold, the Reagan Revolution (as it would be called) seemed unstoppable.

During the summer of 1981, football had taken a back seat to my Lennon-Regan obsession. My research branched out from reading newspaper and magazine articles about the two to tracking down old Regan movies and buying up old Lennon records. My hunt eventually led me to the local Used Record store. The local Used Record store was a major after-school hangout for older teen boys, a place for an exchange of ideas — not just strictly about music, but also about culture, politics, etc. I was becoming known as a guy who collected John Lennon records there. And as I was perusing the vinyl, I couldn’t help but overhear Harper, the owner of the place, complaining to a patron about how Reagan was destroying America.

“It makes you wonder what if Lennon’s assassin had failed and Reagan’s assassin had succeeded, doesn’t it?” Harper spoke. “America would be a lot different right now.”

That seemed pretty obvious. If Hinkley had succeeded and George Bush had taken over as U.S. president then the Reagan Revolution never would have happened. Bush didn’t have the charism (nor the idealism) to push for a cockamamie idea like Reagan’s Star Wars initiative. And Bush dismissed Reagan’s “trickle-down” economics as a bunch of voodoo. Tax cuts for the rich, unregulated deregulation, and appointing corporate criminals to head Federal agencies. Bush wouldn’t have done any of that. He was a Washington insider who used compromise and diplomacy to keep the status quo and who was entirely uninspiring to the working-class Regan Democrats. But to the other half of the question: What if Chapman had failed? Would Lennon, a musician, really have changed America for the better?

Lennon was at the peak of his political influence during the early 1970s, before anyone realized the Era of Malaise was actually upon us. Reagan meanwhile, became even more committed to gaining a foothold on the national stage. On a mission to galvanize a new Conservatism, not only in California, but across the entire United States, he became a regular on talk radio programs and the public speaking circuit. He became the voice of Conservatism right as Lennon’s stature as the voice of the hippy generation grew to unprecedented proportions. Lennon was the epitome of the long-haired freak, who smoked dope, talked smack about Jesus, and had a god damned “gook” for a wife (as certain opponents in the media pointed out). He spoke out against the war in Vietnam, spoke up for civil rights, gay rights, women’s rights. He was the epitome of everything Ronald Reagan stood against. By 1971 Lennon’s status hit a new level when he decided to take up permanent residency in New York City. Lennon’s influence was so great by this time that his move to the U.S. prompted both J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI and Richard Helm’s CIA to immediately set up full-time surveillance on him (years later Ronald Reagan would present Richard Helms with the national security medal for distinguished achievement in the field of intelligence). There’s no evidence to suggest that Reagan played any part in the FBI or the CIA’s “investigation” of Lennon, but it doesn’t seem impossible that Reagan would have ordered the FBI and the CIA to investigate Lennon if he had been in Nixon’s shoes in 1972. After all, years later we would see Reagan make a mockery of the rule of law during the Iran-Contragate. Plus, Reagan already had a history of informing on entertainers who expressed anti-government sentiments. Reagan’s introduction to Federal government surveillance came when he was an informant for the FBI during the Red Scare of the 1950s. The FBI asked Reagan, who was a Hollywood actor and president of the Screen Actors Guild at that time, to identify suspected Communists in Hollywood — specifically actors he knew or who had worked with. Reagan turned over dozens of names of suspected commie liberals.

But those were the good old days. Now, in the early days of the 1970s, these liberal commies were out of the closet, demonstrating at sit-ins and be-ins and bed-ins. They were burning bras, burning draft cards. Now these liberal agitators were called hippies and Lennon was their leading voice.

In December of 1971, the Nixon administration identified Lennon as a person who could actually sway the 1972 election. Lennon’s power became clear after he wrote a song for White Panther leader John Sinclair. Sinclair had already served two years of his ten-year prison sentence for possession of drugs. Lennon first performed this new song “John Sinclair” at the “John Sinclair Freedom Rally” in Ann Arbor, Michigan. Lennon sang “You gotta-gotta-gotta set him free” and amazingly three days later Sinclair was set free. This seemingly amazing feat of being responsible for Sinclair’s release from prison put Lennon squarely on Nixon’s radar. Nixon considered Lennon as such a threat that he not only put Lennon on his famed Enemies List, but the Nixon Administration actually hatched a plot to have Lennon immediately deported from the United States.

john sinclair

john sinclairLennon’s influence had a direct effect on governmental actions. His ability to galvanize public opinion against the status quo was at an all-time high. In the wake of Lennon’s successful campaign to free John Sinclair, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover made John Lennon a top priority. According to FBI surveillance of Lennon during this period, the FBI soon found out that Lennon had fallen in with left-wing activists/agitators Jerry Rubin, Abbie Hoffman, and Bobby Seale. With Lennon’s help, these agitators devised a plot in which Lennon would follow Nixon around on the campaign trail, city to city, in order to host anti-Nixon rallies. This was to be nothing short of a coup de tat of the entire media coverage of the 1972 Republican National Convention, with the ultimate intention of influencing the outcome of the 1972 United States Presidential election. The Nixon administration countered immediately by bringing in the CIA. The CIA’s surveillance in fact was part of a secret, illegal CIA program called MHCHAOS, whose reports went directly to the President. Working independently of one another, informants from both the CIA and the FBI were tracking Lennon’s daily movements. Several agents from both agencies penetrated the YIPPIE political organization with which Lennon was associated. The NY police department and law agencies in Miami Florida were involved as well as they plotted to set Lennon up for a drug bust. The intelligence that the agencies gathered on Lennon was disseminated among dozens of organizations ranging from military intelligence to Secret Service to FBI field offices in several U.S. Cities. As a celebrity, Lennon had become used to being stalked, but now it had gone to an entirely different level. The FBI and CIA surveillance of Lennon was ramped up to the point of intimidation. Lennon was shadowed by blunt men in trench coats. Lurking about his neighborhood these professionally trained men followed him down streets and alleys. White vans parked outside his apartment for days on end. Undercover agents in cars tailed them wherever they went. Crackling noises and interference overwhelmed the telephone line whenever he made calls. His property was bugged and federal agents employed the latest tracking equipment and technology. Lennon was even warned that he and Yoko would be arrested for “interstate travel in the furtherance to conspiracy to incite a riot” if they went forth with their plot. Meanwhile, South Carolina senator Strom Thurman met with US Attorney General John Mitchell with the purpose of revoking of Lennon’s visa and proceedings by the Immigration and Naturalization Service to deport Lennon were immediately fast-tracked. In the end, it was Lennon’s obligations to this deportation case and other legal situations that would keep him busily frustrated and unable to shadow Nixon on the campaign trail. The plan for him to invade the Republican National Convention was thwarted.

Likewise, Reagan’s plans to invade the 1972 Republican National Convention were thwarted as well as CREEP (Nixon’s Committee to Re-election the President) was able to marginalize Reagan’s bid for the nomination. But over the next two painful years, as it became evident that the Era of Malaise was indeed upon us, CREEP would prove to lead to the downfall of Nixon, as it was revealed that operatives in CREEP were the “masterminds” behind the break-in at the Democratic National Committee headquarters at the Watergate Office Complex in Washington D.C. Watergate not only had a huge impact on America, but it had a huge impact on both Reagan and Lennon as well. Lennon who was in the middle of his so-called “Lost Weekend” attended the Watergate hearings, and as the proceedings unfolded he began speaking to the press about his suspicion that he had been the subject of FBI and CIA’s surveillance. Ironically it would be the Watergate hearings that prompted Congress to pass the Freedom of Information Act which in turn allowed the pubic to see the depth of the Nixon Administration’s abuse of powers and its illegal targeting of Lennon. Reagan watched Richard Nixon resign from the U.S. Presidency and realized the door for another run at the white house was wide open. And it was at that moment, under these twists of circumstances, that Reagan and Lennon — these two ideologically opposing cultural icons — actually met face to face for the first and only time in their lives. The occasion? An NFL football game, of course.

It was during halftime of the Monday Night Football telecast on December 9th, 1974. The game was at Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum featuring the hometown Los Angeles Rams taking on the NFL squad that represented our nation’s capital, the Washington Redskins. Lennon was there promoting his recently released album, Walls and Bridges. Reagan meanwhile was about to turn the keys to the Governor’s mansion over to the liberal Governor-elect Jerry Brown. Howard Cosell, when asked which icon he wanted to interview on air, immediately replied, “I’ll take the Beatle.”

Then as the two icons waited to go on the air for their halftime interviews, Reagan began chatting Lennon up, explaining some of the rules of American football. Lennon was curious and contentious, receiving Reagan’s chummy manner warmly. Strangely enough, the two men had more in common than met the eye. Both men were idealistic. They both had patriotic middle names that began with a W. John Winston Lennon’s middle name was in homage to the former leader of his home country, Winston Churchill, while Ronald Wilson Reagan’s middle name was in homage to the former leader of his home country Woodrow Wilson. And it was undeniable that both men had a unique charisma that resonated with millions of Americans. They were both followed, if not worshiped, by millions. They were both leaders, men who had started their careers in the entertainment business which eventually led both toward intense interests in politics. Both had been radio stars, TV stars, and movie stars, but there were striking similarities in their personal lives as well. Lennon was the son of a ner-do-well, good-timin’ drunken sailor while Reagan was the son of an alcoholic salesman. Both men had very rocky, and at times, confrontational relationships with their fathers. They both had failed first marriages that produced sons who weren’t afforded the attention that most sons craved. And central to the treks of both men was the fact that they each found their soul mates and fell in love with devoted and loyal women who seemed to worship them in every way. Reagan, who was an actor, married Nancy who had been an actress. And Lennon, a musician and an artist, his wife Yoko had been an artist and a musician as well. The two second wives, Yoko Ono and Nancy Reagan also shared something in common. They both used astrological charts and celebrity psychics to plan the major events in their lives. On the day that the Beatles were scheduled to sign the papers that would legally disband the Beatles, Yoko Ono famously prevented Lennon from signing the papers due to bad signs in the stars. Similarly, she would later pull out of the partnering with Paul McCartney to buy the Beatles catalog in the mid-1980s because of the astrological signs (this move actually led to the songs being bought by the king of pop, Michael Jackson right after Jackson joined forces with the Reagan’s in Nancy’s Just Say No campaign). Nancy’s connection to the stars was just as devoted as Ono’s as former Reagan staff members revealed. News stories came out about how every major move and decision the Reagans made was cleared in advance by a celebrity psychic Joan Quigley of Sand Francisco. Which leads one to wonder if the Lennon-Reagan meeting was more than just chance?

SF psychic for the Reagans, Joan Quigley

SF psychic for the Reagans, Joan QuigleyWhatever the case, a lot changed for both Lennon and Reagan after their face to face meeting. A few days later, while at Disney Land, Lennon signed the document that officially dissolved the Beatles. Reagan meanwhile, just days later met with South Carolina Senator Strom Thurman (who like Reagan had switched from the Democratic Party to the Republican Party) to seek his support in his bid for the Republican nomination in 1976. Thurman backed Gerald Ford instead and Ford won the Republican nomination. But in the confusing post-Watergate atmosphere, liberal Democrat Jimmy Carter beat Ford in 1976 for the U.S. Presidency. Meanwhile, Lennon gained permission to become a permanent resident of the U.S. and he and Yoko gave birth to their son Sean. With Carter in the white house and Nixon resigned in shame, it seemed like a good time for Lennon to slip out of politics, out of pop culture, and out of the public eye. The hippies had won, and for the time being Lennon decided to focus on being a house husband. But as the hippies became comfortably confused and numbly apathetic during the Era of Malaise, Reagan was working harder than ever. Narrowly missing the Republican nomination in ’76, Reagan took doing radio commentary, writing a weekly newspaper column, appearing on TV and delivering speeches that galvanized political coalitions. He became the leading voice of the Conservative, Christian Capitalistic Right and he beat out George H.W. Bush for the Republican nomination in 1980. He then chose Bush as his running mate and won the white house less than a month before Lennon was assassinated.

It may seem like another bizarre synchronic connection that Lennon retired shortly after meeting Regan and then came out of retirement right as Reagan was winning the white house. And it may seem like a strange coincidence that just days after Reagan won the white house, Lennon released Double Fantasy, the final album during his lifetime. Harper, the owner at the local Used record store in my hometown, felt certain that this meant Lennon was preparing to become politically involved again. But after listening to Double Fantasy (and then later the posthumously released Milk and Honey) I couldn’t find anything to support that. As a 13 year old, it was hard for me to relate to Lennon, a 40-year-old guy who was singing about sitting around his house all day watching TV, baking bread, and taking care of his small son. His hit song “Woman” came off as the pathetic pandering of some pussy-whipped, middle-aged rich guy. “Watching the wheels” seemed to be the musings of a man who had no interest in the idiotic tit-for-tat popularity of politics. In fact, he seemed like a man who saw little difference between the political game and the NFL game. In the end, it was all just a game and he, like most other citizens, were simply on the sidelines or in the stands, cheering for one quarterback or the other.

Reagan was the quarterback the Conservatives rooted for throughout the 80s. He ushered in an Era of Corporatization that completely transformed the American system. He lowered taxes for the corporations, deregulated banking, fostered the “revolving door” that put corporate criminals in charge of the government agencies they formerly violated, and then allowed them to return to the corporate boardrooms several million dollars wealthier. Corporations were taking over the media, taking over education, taking over the health industry, the food industry, taking over the military, taking over America.

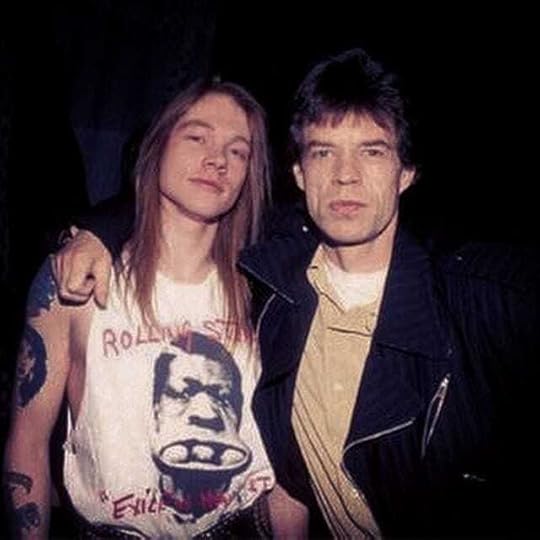

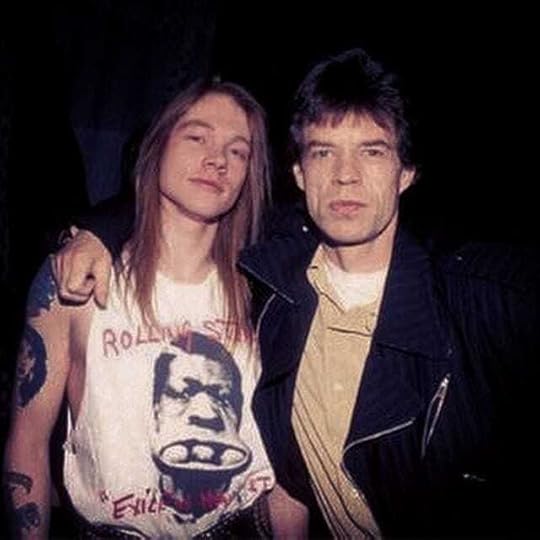

I left my hometown in 1986. I went off to college and then off to the big city, never to see Harper or his used record store again. I thought about him though, and his certainty that America would have been different had Lennon lived. And somehow, as I saw America transforming before my eyes throughout the 1980s, I wanted to be convinced of that. There was no doubt that there was no one who was really sticking their neck out like Lennon had in the early 1970s. It was just the opposite in fact, instead of opposing the institutions, the 80s saw Rock stars becoming the institutions. Even though they were climbing all over one another to be seen as the politically relevant Reagan counter-Revolutionary sirens — Bob Dylan, Neil Young, Bruce Springsteen, David Bowie, Mick Jaggar, Bono, even Lou Reed took up all sorts of political causes and got involved in “fund-raising” charity events, concerts, videos, etc. There was a new cause with every new political breeze. Which one was it this week? Was it USA for Africa? Hands Across America? Live Aid? Rock the Vote? Farm Aid? Artists against Apartheid? In reality, their political activism was so utterly corporatized that it was impossible to tell whether these artists were promoting a cause or promoting their corporate sponsor. It was all so safe and so fucking lame and so irrelevant. And I’d like to think that John Lennon would not have been reduced to all of that. I’d like to think that he would have been the exception. But in all honesty, my days of hero worship and believing in Rock icons are gone and if Lennon had survived instead of Reagan then it really wouldn’t have changed the U.S. Not much, if at all. And that’s reality.

[image error]August 27, 2023

when Mtv killed classic rock

The exact moment was January 3, 1984 — that was the day that Bobby Gutley realized that Rock was dead. I was 15 years old, sitting Indian style in the middle of Gutley’s living room on shag carpeting that smelled slightly like cat urine. Gutley, myself and just about every other kid I knew were glued to a TV set at that moment, in basements, living rooms and bedrooms all across town, awaiting the premiere of Van Halen’s latest video ‘Jump’ on Mtv.

My friendship with Gutley went back to grade school, not only had we played baseball and football together, and shot BB guns at each other’s heads, but we had spent a thousand afternoons peddling our bikes over crooked pavement and cracked sidewalks, through gravel back alley short cuts, puddle hopping our way to the snack shop/filling station a half mile across town. We listened to Ted Nugent and Foghat on the jukebox and oogled cheap porno magazines that we stashed inside our Mad magazines as we ate hot dogs and chips, and drank Cokes. We were from the same socioeconomic strata: poor, small-town white boys who lived on the run-down side of the tracks. Neither one of us had a “present’ father. Gutley’s old man was a truck driver who had been on the road since Gutley was a little kid and then one day just never came back. Gutley’s mom worked two jobs and never had the time to find a replacement dad. My situation wasn’t any better, and in fact, this was a pretty common arrangement in our neck of the woods. The divorce rate in America had doubled every single year from 1965 to 1975 — and all these divorces had created a subculture of “latchkey” kids, kids who came home after school each afternoon to an empty house. We were left to fend for ourselves. We could have turned to drugs or alcohol or to the Bible or cable TV. But Gutley and I turned to Rock music. That was our religion. It created our ethos. There was a certain way of doing things, there were standards that, if you followed, would get you through anything in this universe. Rock and Roll provided the code, through the cues and clues and attitudes found on the vinyl records, on the cassette tapes and 8-track tapes, the album covers, the electric sounds recorded in analog, the lyrics, the liner notes, the Rock magazine articles or late night music shows — it all revealed and reinforced the Rock ethos to us. And we believed in this ethos with as much passion and certainty as any devoted religious zealot believes in the wisdom of the Lord. Neil Young sang our anthem, “Hey, hey, my, my. Rock and Roll will never die.” But now, sitting in front of the TV in Gutley’s living room, about to witness Van Halen’s “Jump,” the Rock ethos that we had been raised on was on the verge of collapse.

Gutley cranked the volume on his television set to the point of numbed distortion. The Mtv ‘World Premiere Video’ logo dissolved into the screen and the boys from Van Halen — Gutley’s last hope for Classic Rock — jumped out. Van Halen was Gutley’s band. He had three Van Halen concert shirts, he had Van Halen patches covering his jean jacket, he drew the Van Halen logo on his notebooks at school, he had a Van Halen poster scotch-taped to his bedroom door, and he had every Van Halen album ever recorded within arm’s reach of his record player. But… it had been nearly two years since Van Halen’s last release and the Rock landscape had changed dramatically. How much it had changed was about to become painfully obvious as the belated members of Van Halen jumped to life on the TV screen and began striking their calculated rock poses. Something was wrong. First of all, Eddie Van Halen, the guitar god of our generation, was fingering out some nursery rhyme chord progression on — what the fuck! — an Oberheim OB-8 synthesizer? Eddie had this goofy, regurgitated grin smeared across his face as if he had just farted in a crowded elevator. Then wham-bam! Out pops the spandex-clad Diamond David Lee Roth bounding across the screen in his un-laced hi-tops giving us all a head-cheerleader “We’ve got spirit, Yes we do, we’ve got spirit how bout you?!?” leg-splitting high kick followed by some sort of Karate Kid backward ass flip thing that was shown in slow motion. Every other shot in fact was a glamour shot of David Lee Roth doing cartwheels or fluffing his hair in a gesture that immediately brought to mind a cheesy Shampoo commercial in which a female hair model made the exact same gesture while singing “I’m gonna wash that man right out of my hair!” What the fuck is this? This wasn’t right. This was wrong! And not only were they looking and acting like total douche wads, but the song was for shit! Doot-doot-doot-doot. Doot-doot — deet-dah-dah-doot. “Jump! Might as well jump!”

The disappointment in Gutley’s face couldn’t have been more clear. His eyebrows furled, the edges of his mouth took a downward turn. The sprinkle of Alfred E. Newmanesque freckles on his nose seemed to instantly fade away. He suddenly appeared very old. “Is that it?” his expression said. Is that all that our generation of Rock has to offer? I knew what Gutley wanted. He wanted Pete Townsend smashing his guitar across his amp, he wanted John Lennon saying the Beatles were bigger than Jesus, he wanted Jimmy Page pulling out a violin bow and butt fucking his guitar with it, he wanted Jimi Hendrix bowing down in front of his flaming guitar and giving praise to the Gods above for blessing him with the calling. But what had we gotten? Synthesizers! Synthesizers and lip-synching and drum machines and spandex and cartwheels… And M fucking TV.

M fucking TV. Maybe M fucking TV was just the scapegoat, maybe it was just a symptom and not the disease. But if you were a teenager in the early 1980s the one thing you remembered was not what you were doing when the hostages in Lebanon were released or what you were doing when Oliver North testified to Congress about illegal arms deals. What you remember is the first time you ever saw Mtv. I was as guilty of this fascination with Mtv as any. It was late 1981 and my mother’s second husband Joe had just splurged 9 dollars a month to provide the family with cable TV. Every night after that, Joe would pass out on the sofa with a Pabst Blue Ribbon clutched in one hand and the remote control clutched in the other. Then one night, bored with Marty Stouffer’s Wild America reruns, I surgically removed the remote from Joe’s hand and started channel surfing (with only 13 cable stations available, surfing the TV waves wasn’t all that daunting). When I clicked the channel to Mtv my jaw just dropped. The first thing I saw was a split-screen image of this spiky-haired, fair-skinned doll woman (Laurie Anderson) singing “O Superman” to the beeping sound of a digital telephone dial tone. Beep-beeep-beep-beep. I couldn’t take my eyes off it — “What is this?” But if that wasn’t baffling enough, what immediately followed was this pasty-faced, pouty-lipped Euro-dude with a blond, ice cream swirly of a hairdo (and who was dressed kinda like a pirate from outer space) who was wheezing about at the funhouse mirrors in what seemed to have been the Men’s room on the Millennium Falcon, hugging himself as he sang “And I raaaaa-an, I ran so far aw-aaaay”. Spacier still was the heaven-ish, chiming, mesmerizing echo-effect guitar riff ripping up the sound space all around him. “What the hell is going on here?” Had Martians invaded the frickin planet and taken over the TV waves? Had some future race of humans found a way to transport images back in time

through satellite technology?

Whatever it was, I couldn’t take my eyes off it. But, maybe to fully understand how alien Mtv was at that time, you had to have lived through the 1970's…and lived through them in a small town because smalltown 1970’s was a place and time where the old weird America still hung out. It was a time and place before corporatization dominated the culture, before the uniformity of thought and action that dictates the 21st century’s politically correct reality had taken over the culture. In old, weird America life was like a sepia-tone-hued film that was slightly blurred, slightly out of focus, slightly off, slightly rusted. Small town 1970s was a place and time where people didn’t take much effort in deciding what clothes to wear or even whether they should comb their hair or not. It was a time and place that was becoming extinct.

By the end of the 1970’s small-town Americans were living in a country that had lost its first war ever (Vietnam) and whose very foundation of government had been crippled by Watergate. It was a country that was in the throes of an economy that was so bad that new words and phrases (like “stagflation” and “the misery index”) had to be created to describe it. After 25 years of post-WWII prosperity, small town 1970’s was facing inflation, stagnation, increasing unemployment. We had an energy crisis, a hostage crisis, oil embargoes, we had large corporate chemical companies pumping cancer-filled smog into the environment and toxic-infested factories pumping industrial waste into our waterways at such a rate that it was literally causing entire rivers to ignite into flames. We read of white flight, a phenomenon that led to a neglect of the inner cities and turned urban neighborhoods into petri dishes of crime, corruption and decay. New York City had actually gone bankrupt and had to ask the Federal government for a bailout. In a small town, we didn’t know what to think about that. But the stories of tens of thousands of draft dodgers and street criminals forming an underground population of shady characters with fake identifications and living in cults or bouncing from safe house to safe house was concerning. It all added up to what the peanut farmer from Georgia (i.e. President Jimmy Carter) called a “crisis of confidence”. Everyone seemed kinda bummed out on some level, or else drugged up and out of touch, sitting around in lawn chairs, drinking, smoking, wondering what they were gonna do next. Then, in an election with the lowest voter turn-out in history, our apathetic response was to elect some bumbling, brill-creamed, old-time Hollywood B-movie actor who was best known for co-starring with a chimpanzee and saber-rattling against hippies and Communist.

But then, in the mist all this confusion, crisis and malaise, came M fucking TV, a window to a land where things were different — an alternative universe where things were bright and beautiful, colorful, obtuse, upbeat and just plain fucking weird. A shiny, cool, new wave of artists from Europe with mathematically honed “post-punk” sounds were just beginning to overpopulate the pop charts in Europe and marching toward America in the next British Invasion. Their mission? To provide American teens with their soundtrack for the 80s. And Mtv was there to broadcast it.

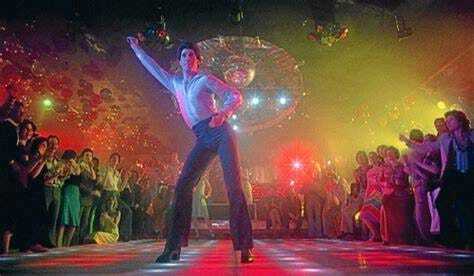

It had taken less than two summers, for nearly every teenager in the country, including those in my small town, to become totally infected by the Mtv virus. In those two years, neither I nor almost any other teen across the land could take their eyes off of Mtv. What could be of greater fascination in the life of a 13-year-old who had just survived the 70s, than seeing flashy-attired pop musicians queer-dancing about under flashing, multi-colored lights in neon-tubed, disco-mirrored expressionistic sets filled with the mise en scene abstractions of futuristic sculpture and pop art designs — and all to the sweet, sugar-synthed sounds of electro-pop, precision that was riddled with rhythmic dance beats that permeating the air like zig-zagging lasers shot from an arcade machine? AmeriTeens were mesmerized, hypnotized. So much so that no one had paid that much attention to the fact that in those two years, Rock had forever changed. By the premiere of Van Halen’s “Jump” video Classic Rock had been replaced by two equally destructive yet diabolically opposed forces: First, New Wave Synthesizer Pop, followed quickly by Hair Metal. In the high schools, and in the shopping malls, at the pinball hangouts, and on the radio. There was no stopping these two forces. And then when it seemed that things could not get any worse, here came Michael Jackson. And just like that Mtv was ruining everything. And I mean everything.

I looked at Gutley. He resembled a hard-boiled egg about to explode. Literally explode. The Van Halen video had awoken a primal instinct in him. The look on his face was disgust, utter disgust. He had had enough: enough of the jerry-curled, glittery, soulless twits with their one white glove and their ‘moon walking’ across the screen, enough of the permed-haired, hipster-vested snoot-worthies who crooned across the ballroom dance floor singing “Everybody wang chung tonight”, enough of the caked-on, make-up faced, chinless turds in parachute pants singing “Shout, shout! let it all out”, enough of the poodle-groomed, guy-liner infested Pop Metal poseurs singing power ballads that were polluted with ridiculously formulaic guitar solos and pussy-ass guitar riffs. But most of all, he had had enough of what Mtv had done to Rock music: it was turning our Rock prophets into sideshow barkers and trained monkeys, replacing balls-to-the-wall guitar riffs with synthesized disco, it was spoon-feeding American teens lollipops and bubble gum over meat and potatoes. Maybe this shit was acceptable to the typical high school robots, but for Bobby Gutley a line had been crossed. Something went ‘snap’ inside his head. This was supposed to be an important moment, an important album, an important song by the best hard rock band in the world. But instead…we got served this shit sandwich. It just wasn’t right. There was something missing. It didn’t feel like it should. And it wasn’t just the music, it seemed like something huge, not just Classic rock, but something bigger had died.