Justin Gregg's Blog, page 6

June 11, 2013

The “Dolphin Rape” Myth

Google the term “dolphin rape” and you’ll find countless references to male dolphins raping female dolphins, males raping other males, gang rape, and even dolphins raping humans. You might even find this hoax webpage claiming that dolphins regularly kidnap swimmers and take them to a “rape cave.” Head over to Google Scholar, however, and you will find exactly zero references to “dolphin rape” in the scientific peer-reviewed literature.

The reason for this discrepancy is quite simple: the term rape cannot be used to describe the kinds of behavior scientists have observed in dolphins. The central problem is that the legal definitions of rape include a lack of consent on the part of the victim, and we simply cannot know the extent to which dolphins or other animals are able to give consent. A non-consensual act like rape has “moral and legal implications” that are only relevant in the human world, which is why animal scientists (pretty much) stopped using the term altogether in the early 1980s. The correct scientific term to describe when a male aggressively restrains a female in order to mate is forced copulation. Forced copulation has been observed in ducks, lizards, monkeys, fruit flies, crickets, orangutans, chimpanzees, and countless other species.

But not dolphins.

Despite the media frenzy around the idea of dolphin rape, it’s primates, birds and insects that are the forced copulation aficionados, not dolphins. What follows is a brief rundown of all of the aggressive sexual behaviors that scientists have observed in dolphins that often find their way into popular reports discussing dolphin rape:

Sexual Coercion: Sexual Coercion is a term describing a suite of behaviors observed most frequently in the bottlenose dolphins of Shark Bay Australia and Sarasota Bay Florida. Individuals or groups of males use a variety of coercive tactics to increase their chances of mating with females. In Shark Bay, groups of male dolphins are often seen in the company of an individual female for extended periods of time (referred to as a consortship). Sometimes these males begin the consortship by herding (i.e., chasing and corralling) the female, although other times the female appears to enter the consortship willingly. These males sometimes use aggressive behavior to keep the female close to them and to fend off rival males, and it’s during these consortships that mating takes place. In Sarasota, males also follow females around when it’s time to mate (a form of mate guarding), but rarely engage in aggressive behavior directed at the female like in Shark Bay. Dolphins might use other tactics to persuade a female to mate with them, including committing infanticide (i.e., killing calves) so that the females will come into estrus and be more receptive.

But here’s the thing: even in the clearly aggressive coercion scenarios witnessed in Shark Bay, researchers have never witnessed forced copulation. The kind of coercion being described here is indirect in that these tactics ultimately result in males persuading females to mate with them, but not directly forcing themselves on the females. The scientific experts studying the Shark Bay dolphins had this to say about forced copulation in a recent book:

“We have no evidence of direct sexual coercion in dolphins, including forced copulation or other behaviors directly associated with male attempts to mate.”

In other words, if forced copulation should be considered the non-human animal equivalent to rape insofar as it appears (to the human observer) as if the female has not given consent, then this still has never been observed in dolphins. This fact alone is a strong argument against the use of the word rape to describe any dolphin mating strategies.

Socio-Sexual behavior:

The below video has been mislabeled as “Dolphins Mating,” and purportedly shows two males and one female dolphin. In fact, there are three male dolphins in this video. This group of young males is engaging in what scientists call socio-sexual behavior. This is a blanket term that describes any social behavior involving penises that does not involve a male trying to impregnate a female. Sometimes the dolphins simply rub all over each other while brandishing erections, and sometimes they actually insert their penises in each other’s anuses or genital slits. Unlike true mating, which usually take the form of the male swimming belly-to-belly underneath a female, socio-sexual behavior often involves the male approaching the other dolphin (male or female) from behind or the side. Sometimes it looks rather brutal and aggressive, and sometimes, like in the below video, the animals seem pretty chill. There are a variety of reasons dolphins engage in these behaviors, ranging from establishing or maintaining social bonds and friendships, to blowing off steam, punishing rivals, or simply having a grand old time. It’s difficult to know exactly what is going through the dolphins’ minds when watching socio-sexual behavior unfold, and whether or not any of the observed penile penetration is consensual. Regardless, it does not resemble forced copulation.

Mounting: You can easily find examples online of dolphins with erections and thrusting behavior directed at human swimmers (like here, and here). It’s impossible to know if penetration is their intention (i.e., some form of penetration being another criterion in the definition of human rape), or if it’s the dolphin equivalent of a dog humping your leg. Mounting behavior (which does not always involve penetration, especially since females sometime do the mounting) has been studied in a number of animal species, and the list of proposed functions for this behavior is diverse: play behavior, solidifying maternal bonds, dominance, aggression, establishment and maintenance of social bonds, conflict resolution, and of course sexual gratification. Mounting behavior in dolphins is widespread and is a form of socio-sexual behavior. It involves dolphins of all ages and both sexes. Juveniles and calves will sometimes mount their mothers (and vice versa) and females will mount males. Despite documented mounting attempts involving dolphins and humans, I have found no verified accounts of a male dolphin having ever penetrated a human orifice with his penis (against their will or otherwise).

So here’s the bottom line: calling any of this behavior rape trivializes the word rape. It either downplays the horrific human behavior of rape by jokingly misapplying it to quirky animal behavior, or unnecessarily vilifies what is, for dolphins, a diverse catalog of behaviors that might not cause the dolphins involved very much stress, and might even be consensual 100% of the time. In most cases involving male dolphins using aggressive strategies to mate with females, the correct term is sexual coercion, which is NOT synonymous with rape. Unlike rape, sexual coercion might involve consent on the part of the female, and involves many indirect coercive behaviors (e.g., herding, infanticide), and not just forced copulation. In any event, forced copulation as a sexual coercion technique has never been observed in dolphins. In cases where males are directing their penises at the bodies and orifices of other dolphins where reproduction is not the goal, or engage in mounting behavior, the correct term is probably socio-sexual behavior. Again, socio-sexual behavior might involve consent, and does not always involve penetration or forced copulation.

The dolphins are rapists meme easily lends itself to being a trendy t-shirt, or link-bait headline, but rape is undoubtedly the wrong term to apply to dolphin behavior. It is a loaded term that really should be used solely to describe the fundamentally horrific, and uniquely human crime of rape as defined by the law. There is no dolphin equivalent.

***************

Further reading on sexual coercion and socio-sexual behavior in dolphins:

Connor R.C., Vollmer N. 2009. Sexual coercion in dolphin consortships: a comparison with chimpanzees. In Sexual coercion in primates: an evolutionary perspective on male aggression against females (eds Muller M. N., Wrangham R. W.), pp. 218–243. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press

Connor, R.C., Wells, R., Mann, J. & A. Read. 2000. The bottlenose dolphin: social relationships in a fission-fusion society. In: Mann J., Connor R., Tyack P. and H. Whitehead (eds.), Cetacean Societies: Field studies of whales and dolphins. University of Chicago Press.

May 29, 2013

Dolphin Assisted Birth: Chumming the Waters with Good Intentions

The Charlotte Observer reported yesterday on a couple headed to Hawaii with the plan of giving birth in the open ocean in the presence of wild dolphins. The interwebs’ WTF-detector went into immediate overdrive, chiding the couple for what was dubbed “one of the worst natural birthing ideas anyone has ever had.”

To be fair to the young couple, this is hardly a new idea. The Sirius Institute – which is purportedly working with the couple – has been offering dolphin assisted births for years, and was even featured in a Penn & Teller: Bullsh*t episode from 2008, when another couple headed to Hawaii to attempt their own open ocean birth. To the best of my knowledge, no human has even given birth in the presence of wild dolphins in the open ocean. However, there are rumors of a (now defunct?) dolphin birthing facility in the Black Sea and stories of people who have given birth in dolphin facilities in Egypt. The Sirius Institute and other dolphin assisted birth proponents make fantastical claims that babies born in the presence of dolphins will show anything from having larger brains to being ambidextrous. For anyone with a soft spot for skepticism, these claims are highly suspect, and it’s not a big leap from raising an eyebrow to opening mocking those with dolphin-birth aspirations.

But I have had personal contact with a handful of people who reached out to my research organization asking for info about the possibility of giving birth near/with the wild spotted dolphins we study in the Bahamas, and after a few conversations with these folks, I was pleasantly surprised at how entirely reasonable their intentions were. Fortunately, I was able to offer them some sound advice as to why dolphin assisted birth in the open ocean is a bad idea. The interwebs has been offering its own brand of “advice” to the young couple, mostly citing examples of the sometimes aggressive behavior seen in dolphins as reasons not to attempt a dolphin assisted birth. Some have suggested that dolphins have been known to “rape” each other and human swimmers (which is wrong – more on that here) which is why they’d make terrible midwives. In reality, with a handful of exceptions, wild dolphins rarely have any contact with human beings, so the aggression/rape/danger issue is really a non-issue. Only a handful of cases of wild dolphins – almost exclusively those “lone-sociable” dolphins that seek out the company of human swimmers – have been known to interact aggressively with human swimmers. But for the most part, wild dolphins simply ignore humans. Anyone trying to coax wild dolphins to attend a birth is almost certainly going to be facing a scenario where the dolphins have absolutely no interest in even approaching them, let alone hanging around until the baby arrives.

Here are two excellent reasons why it is a bad idea to want to be involved in dolphin assisted birth in the open ocean:

1) Giving birth in the open ocean means that you are less likely to have access to trained medical professionals and medical equipment that will be able to help in the event that something goes wrong with the birth. While it is entirely possible to mitigate these risks by stowing medical equipment and an army of obstetricians, midwives, and doulas on a nearby boat, swimming in the open ocean while giving birth certainly brings with it a higher risk of complications than, for example, giving birth in a hospital or birthing clinic. So whatever benefits you think might exist due to the baby being born in the open ocean need to be balanced with the risk you are assuming on behalf of your unborn child by being so far away from the proper resources needed for a safe birth.

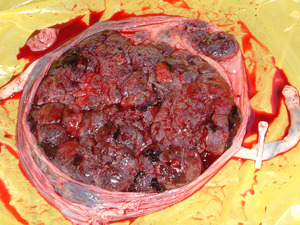

2) The ocean has sharks in it. Sharks are attracted to things like blood, body fluids, and the thrashing around of animals in distress (i.e., everything that goes along with the birthing process). By swimming in the open ocean while leaking blood, you are essentially chumming the waters. This is not a joke. While the jury is still out as to the extent to which sharks are attracted by human blood, there is a very real risk that they are. Sharks rarely attack people, but if you happen to be attempting a water birth in an area where some of the more dangerous species are lurking (e.g., bull sharks, tiger sharks, great white sharks), there is a risk that the body fluids released during the birthing process will increase the chances that these large predators will come by to investigate, and might just decide to take a bite of you or your newborn. It is not the case that you won’t find sharks in areas where dolphins live. Dolphins live in the exact same waters as most shark species, and spend a large part of their day looking out for and avoiding sharks. But they are not always successful. Wild dolphins  are often covered in scars from (unsuccessful) shark attacks, which is a testament to how often they interact with them. And young dolphins are especially vulnerable to shark attacks, with dolphin calf mortality rates quite high for the first year of life – likely a direct result of small, slow swimming calves making easy targets for sharks (see above pic). Considering how vulnerable and small and bad at swimming a human newborn is, it cannot possibly be anything other than a really terrible idea to want to put your newborn’s life at risk by having her/him enter the world in waters that might be teeming with hungry sharks that have been attracted by the body fluids released during the birthing process. To make this point even more vividly, I include below a picture of a bucket of chum (used specifically to attract sharks):

are often covered in scars from (unsuccessful) shark attacks, which is a testament to how often they interact with them. And young dolphins are especially vulnerable to shark attacks, with dolphin calf mortality rates quite high for the first year of life – likely a direct result of small, slow swimming calves making easy targets for sharks (see above pic). Considering how vulnerable and small and bad at swimming a human newborn is, it cannot possibly be anything other than a really terrible idea to want to put your newborn’s life at risk by having her/him enter the world in waters that might be teeming with hungry sharks that have been attracted by the body fluids released during the birthing process. To make this point even more vividly, I include below a picture of a bucket of chum (used specifically to attract sharks):

And a human placenta:

So please, if you are considering giving birth in the open ocean, just remember the keyword “chum,” and consider the serious risks to both your and your newborn.

May 14, 2013

Are dolphins conscious?

We currently lack strong evidence for consciousness in dolphins suggests Professor Heidi Harley in her recently published review article appearing in the Journal of Comparative Physiology A. For some (perhaps most) cognitive scientists studying animals minds, this is not a particularly controversial conclusion – a borderline truism. For other scientists – and perhaps for nearly everyone involved in issues of animal rights and animal welfare – the suggestion that dolphins are “not conscious” is simply absurd. Lurking between the truism and the absurdity of non-animal-consciousness we find a centuries-old battle over the problem of what consciousness is, and how on earth we’re meant to determine the extent to which non-human animals are conscious. Harley’s review article provides a quick introduction to this minefield of a problem, as well as a review of the current scientific evidence of consciousness in dolphins. If you’d like a quick rundown of this topic but don’t have time to read this article or the 2,500 year’s worth of philosophical musings on the topic of consciousness, I will provide a handy overview of Harley’s main points in the form of a dialogue between Phil, who represents the “of course dolphins are conscious” point of view, and Emily, who represents the “I think you’ll find it’s a bit more complicated than that” point of view. Take it away Phil and Emily:

Phil: It wasn’t that long ago that you skeptical scientist folks refused to entertain the idea that animals could even be conscious. Remember B.F. Skinner or J.B. Watson? It seems to me that scientists have always been closed minded when it comes to animal consciousness – keen to uphold the idea that only humans could even be conscious.

Emily: That might well have been true a hundred years ago, but when scientists like Donald Griffin started writing about the value of studying animal minds, a whole new field of scientific inquiry popped up, and now there are thousands upon thousands of scientists studying aspects of consciousnesses in animals.

Phil: But why is this still even a question? Isn’t it obvious that every animal needs to create a representation of the world in its mind in order to navigate its environment, find food, mate, etc? Isn’t this what consciousness is?

Emily: Not really. That’s just the way brains process and perceive incoming sensory stimuli. It’s not much different to how a solar panel with a light-sensor is able to follow the direction of the sun. Just because solar trackers can perceive light doesn’t mean that solar panels are conscious, does it? No, the kind of complex consciousness that we know humans experience is called phenomenological consciousness – it’s the subjective experience of those stimuli/perceptions. If a solar panel experienced the light in some way, then it might well be conscious. Of course even if it did, it wouldn’t be able to tell us about it, which is why it’s so hard to investigate consciousness in non-linguistic animals (or solar panels).

Phil: So you’re saying that it’s impossible to study consciousness empirically then? Isn’t that what Nagel said? Are you suggesting that because consciousness is completely private, it’s not possible to study at all? If that’s the case, then what grounds do you have for suggesting that dolphins aren’t conscious?

Emily: I think even Nagel suggested that it’s possible to study aspects of consciousness (even though it is private). It might be hard to study consciousness, but it’s not impossible. The field of cognitive science has in fact been quite busy studying the way brains perceive and process information in ways that result in subjective experience. Have you heard of people with phantom limb syndrome? They might be missing, for example, an arm – but their mind still creates the conscious experience of the arm. Weird cases like this allow scientists to determine exactly how different parts of the brain and the body must be interacting in order to create subjective (conscious) experience.

Phil: But you’re missing an important point. Animals do more than just process stimuli to determine if they have an arm or not, or to track the direction of the sun. Plants can follow the direction of a light source, and maybe even sense when they are missing a leaf or something, and I am not suggesting that this means plants are conscious. I am talking about consciousness in animals like dolphins, that produce complex behaviors, including solving problems, tool use, etc. Surely the ability to think about and thus subjectively experience all of these incoming stimuli is required by any animal in order to produce complex behavior?

Emily: It might seem so, but there is plenty of evidence to suggest that brains can produce rather complex behavior without consciousness. Studies in humans show that we perform so much of our complex behavior unconsciously – from driving a car to investing our savings. There’s every reason to believe that most – if not all – non-human animal behavior we see could be being produced by an otherwise intelligent mind that is not producing subjective experiences of its own decision making processes.

Phil: This seems ludicrous to me. Are you saying that if I see a chimpanzee and a human both solve the same experimental problem (e.g., how to build a tool to reach a banana in a tree), that the human accomplished this via consciousness and the chimpanzee did this without consciousness? Why posit two different explanations for the same behavior? Isn’t that an unscientific approach?

Emily: This gets into the problem of how and when it’s appropriate to apply the argument-by-analogy approach to interpreting animal behavior. Just because an animal behaves like a human, does this mean we should assume its mind functions in the same way? Depending on how one decides to apply Occam’s Razor or Morgan’s Canon, it is possible to suggest that the same behavioral outcome was produced by different underlying cognitive processes, and that we should always assume that the simplest explanation is the likeliest one. So in this case, banana-reaching via unconscious thought for the chimpanzee. Again, a computer might also be able to solve this problem, but we don’t suggest that computers are conscious. One of the main problems we’re dealing with here is that science does not really have a good definition of consciousness. Yes, it’s some form of subjective experience, but it might come in a variety of forms, and thus animals might be conscious in different ways to humans. It’s important to point out that human minds are not better than the minds of other animals – all minds are different, and there is no scale that suggests human minds are somehow the best minds due to our form of consciousness or some other cognitive trait. In any event, it’s really hard to know the extent to which the chimpanzee in this scenario solved the problem via conscious thought as opposed to complex but otherwise unconscious thought. The big question is, how can we test for the presence of subjective experience?

Phil: So we’re back to this problem again. So in what ways have scientists been testing for consciousness in dolphins, and why exactly have you reached the conclusion that “we currently lack strong evidence for consciousness in dolphins?”

Emily: Scientists have given dolphins the mirror self recognition (MSR) test. Having some kind of awareness of oneself – whether it’s awareness of one’s body or of one’s own mind – is certainly linked to the idea of consciousness. For these tests, dolphins were marked with a kind of dye on their bodies, and if they then swam over to inspect the mark in a mirror, we could conclude that the dolphins must know that it’s themselves they are seeing in the mirror. This then is some kind of self awareness.

Phil: So did dolphins pass the test?

Emily: For the most part, yes. Although not everyone is convinced that they did. Dolphins, unlike chimpanzees or other great apes (which also pass the test) don’t have hands, so it’s hard to know for sure that they were truly inspecting the marks on their bodies. Chimpanzees can reach up and touch the mark, which makes it obvious what they are doing.

Phil: So if they passed the MSR test, then dolphins are self-aware, no? And if they are self-aware, they must have some sort of subjective experience of themselves, which means they are conscious, right?

Emily: Well, the problem is that being able to recognize one’s body in the mirror (that is, recognizing an external representation of one’s body) might not be the same thing as having a representation of one’s own mind (i.e., a sense of self). So passing the MSR test might not even be a sure test of self-awareness, let alone subjective experience.

Phil: Well what about those studies of metacognition in dolphins and other animals. Isn’t metacognion the same thing as consciousness?

Emily: Dolphins have indeed been tested for metacognition. In these experiments dolphins were able to “report” that they were uncertain as to whether or not a tone they were hearing was a low or a high tone, which meant that they must have known something about their own knowledge. But depending on how one interprets these results, they don’t necessarily suggest full blown subjective experience of that knowledge.

Phil: So hold on a second – are you saying that this is down to a matter of interpretation? That there are scientists who suggest that these and other studies are evidence of consciousness in dolphins?

Emily: Yes, that is indeed the case. Some dolphin scientists, like Lou Herman, suggest that these studies, as well as his studies of dolphins’ abilities to imitate their past behavior, indicate that the most likely interpretation is that dolphins have some kind of higher-order thinking going on that might be similar to consciousness.

Phil: So why are you saying that the evidence is lacking?

Emily: I think that most cognitive scientists take this evidence to mean that it’s certainly possible that dolphins are conscious in a similar way to humans, but that the results of research at this stage have yet to provide us with the smoking gun suggesting dolphin consciousness. In the coming years, we’re likely to see new experiments that are better designed to ferret out the presence of consciousness in dolphins and other animals. But at this stage, there’s just not enough evidence to draw strong conclusions.

Phil: So it’s somewhat a matter of interpretation?

Emily: Yes, I’d say so. Scientist still have a poor understanding of how to define or test for consciousness in animals, so there’s a lot of wiggle room when it comes to interpreting these results. But it’s important to emphasize that the current scientific evidence is simply not strong enough at present to make final conclusions.

Phil: You’re leaving the door open for the possibility of consciousness in dolphins then?

Emily: Of course! Scientists always leave the door open, and I’d love to be the one to design an experiment that solves the problem of how to test for subjective experience in dolphins.

Harley HE (2013). Consciousness in dolphins? A review of recent evidence. Journal of Comparative Physiology A PMID: 23649907

Harley HE (2013). Consciousness in dolphins? A review of recent evidence. Journal of Comparative Physiology A PMID: 23649907

April 29, 2013

Dolphin brains and the Aquatic Ape Hypothesis: a dubious link

Did dolphins evolve large brains because they ate seafood? This was a suggestion put forth by a proponent of the Aquatic Ape Hypothesis (AAH) in a recent article in the Guardian. The AAH attempts to explain the origins of unique human characteristics (e.g., hairlessness) by suggesting that we evolved in an aquatic environment. The recent Guardian article garnered a lot of negative attention from AAH detractors (i.e., nearly the entire scientific community) soon after it was published. For those of us interested in dolphin science, there is a fantastic – if bizarre – reference to dolphins in the closing paragraphs:

“Docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) is an omega-3 fatty acid that is found in large amounts in seafood,” said Dr Michael Crawford, of Imperial College London.

“It boosts brain growth in mammals. That is why a dolphin has a much bigger brain than a zebra, though they have roughly the same body sizes. The dolphin has a diet rich in DHA. The crucial point is that without a high DHA diet from seafood we could not have developed our big brains. We got smart from eating fish and living in water. (SOURCE)

The idea that omega-3 fatty acid is “why a dolphin has a much bigger brain than a zebra” is not supported by anything from the scientific literature on dolphin brains as it pertains to cognition and behavior. As it stands, the leading hypothesis as to why dolphins evolved large brains is that they required the complex cognition generated by a large cortex in order to navigate their complex social worlds (i.e., the social brain hypothesis). Past hypotheses have involved the need to process complex auditory information (from their echolocation), or that large brains helped dolphins to generate heat. But nowhere in the scientific literature on dolphin brain evolution (as it pertains to behavior/cognition) is there any mention of “fish oil” being a continuing factor.

Of course I am not all that familiar with brain evolution as it pertains to fatty acids. So just to be sure I wasn’t missing something from the literature, I did a quick Google Scholar search for Docosahexaenoic acid and dolphin brains. I found an article from 1987 co-authored by (as far as I can tell) the same Dr. Michael Crawford quoted above wherein he states THE EXACT OPPOSITE of what he said in the Guardian:

The data demonstrate that, despite the high proportion of n-3 fatty acids in the marine environment, the free-living dolphins have remarkably high concentrations of arachidonic and other n-6 fatty acids in their tissue or membrane phosphoglycerides. In this respect, they are similar to land mammals. (Page 679)

In other words, dolphins don’t seems to have a diet rich in omega-3 fatty acids (or at least they don’t store much of it in their tissues) but instead have the same kind of boring-old n-6 fatty acid concentrations we find in small-brained zebras. So it follows that omega-3 can’t then be a contributing factor in hypotheses involving dolphin brain evolution (one would think). Maybe recent literature has overturned this finding (and I am sure this line of research is more complex than I understand it to be at first glance), but even if there is a strong link between ingesting DHA and brain size, we’re left with a much more fundamental problem: eating fish oil doesn’t cause brains to evolve to be larger in some weird Lamarckian way. To explain the evolution of large brains, we need to determine what selective pressures made having a large brain (and the complex cognition that goes with it) an advantage to dolphins’ ancestors. You can’t just say “fish oil did it” until you have an adaptive explanation to go along with it. Here is how the fish oil explanation (as portrayed in the Guardian) looks alongside the current leading hypotheses as to why dolphins evolved large brains:

–> Because of the need to navigate a complex social system, dolphins evolved lager brains

–> Because of the need to process echolocation signals, dolphins evolved larger brains

–> Because of the need to fish oil, dolphins evolved larger brains

One of these things is not like the other.

Is the suggestion really that eating seafood leads to the evolution of larger brains? This can’t be the whole argument. If so, how do we explain large brains not having evolved in sea lions, seals, or other fish-eating marine mammals? Or for sharks? Or for fish-eating birds? Or for fish that eat other fish? Obviously, simply ingesting fatty-acids is not enough. I suppose that one can make the case that a combination is required; selective pressure driving the evolution of large (intelligent) brains and the presence of fish oil in the diet. This explanation does exist to explain the evolution of the human brain. But this then does not explain the evolution of large brain size (relative to body size) in other intelligent non-fish-eating-primates like Rhesus monkeys or chimpanzees. Or vegetarian elephants. Or dolphin species that don’t eat fish (e.g., mammal-eating killer whales). Nor does it explain the fact that we see intelligent behavior in non-fish-eating-small-brained species like scrub jays. The whole idea sounds like a just-so story that just-ain’t-so, and isn’t really helping the Aquatic Ape Hypothesis gain much traction with skeptical scientists.

April 22, 2013

Dolphins sensitive to Ebbinghaus illusion, just like humans

Pop Quiz: which of the two orange circles is larger?

If you think that the circle on the right (the one surrounded by the smaller blue circles) is larger, then you are either a human or a dolphin, but not a pigeon. As it turns out, both orange circles are exactly the same size – but your visual system is influenced by the presence of the surrounding blue circles, resulting in an optical illusion whereby you perceive the orange circle on the right as larger. Pigeons, on the other hand, are influenced by the blue circles in exactly the opposite way, perceiving the circle on the left as larger.

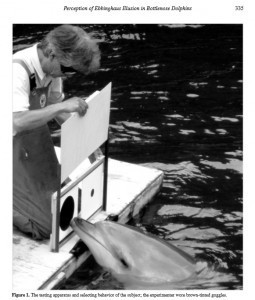

This illusion, called the Ebbinghaus illusion, was first created by the German psychologist Hermann Ebbinghaus in 1901. Recently,researchers tested dolphins for the first time to see if they might be sensitive to the Ebbinghaus illusion. After first teaching the dolphins to reliably choose between larger and smaller shapes (see image below), they were shown a a version of the Ebbinhaus illusion, and, just like humans, chose the circle surrounded by the smaller “inducer” circles as being larger in 84% of trials.

It is difficult to say what being susceptible to this optical illusion might mean in terms of how complex an animal’s understanding of objects might be. Studies with other animals have led scientists to reach polar opposite conclusions. One study found that baboons did not perceive the illusion, which the authors suggested might mean that humans, as opposed to baboons, adopt a more “global mode” of object perception, resulting from cognitive skills that evolved recently in humans but not other primates. Another study found that four day old chickens were sensitive to the illusion, which the authors suggest might point to the ancient origins of a visual perceptual system generating this illusion in a vast number of species. In any event, we can now add dolphins to the list of species that are sensitive to the Ebbinghaus illusion.

Citation below

Murayama, T., Usui, A., Takeda, E., Kato, K., & Maejima, K. (2012). Relative Size Discrimination and Perception of the Ebbinghaus Illusion in a Bottlenose Dolphin (Tursiops truncatus) Aquatic Mammals, 38 (4), 333-342 DOI: 10.1578/AM.38.4.2012.333

April 15, 2013

Is that a dolphin whistle I hear? No, it’s either a submarine or Harland Williams.

claimtoken-516ec066cd42e

As we all know from watching The Hunt for Red October, submarine sonar operators have an almost super-human ability to identify underwater sounds. They can tell the difference between different types of military ships based solely on the sound produced by the engine, and it would be almost impossible to transmit man-made communication signals that a sonar operator couldn’t identify. But Chinese scientists have found a way to deceive even the best sonar operators, and they seem to have taken their lead from this scene from Down Periscope where Kelsey Grammer’s crew fools an enemy submarine into thinking they are a whale by having ‘Sonar’ Lovacelli (played by Harland Williams) imitate whale sounds. In this scene, the enemy sonar operators dismissed the sounds they heard as a “biologic,” and the crew of the USS Stingray was saved (whale sounds start at 1:04):

It seems Mr. Williams was onto something. In a recently published scientific article, Chinese scientists described how they were able to hide information in artificial dolphin vocalizations with the goal to have sonar operators dismiss these covert communication signals as being natural dolphin sounds. The system works by first transmitting a series of dolphin whistles that synch up both the sending and receiving systems. This is followed by a series of dolphin click sounds – the same kinds of clicks used in dolphin echolocation. By varying the time delay between the clicks, the scientists were able to include up to 6 bits of binary data, allowing for a rate of 37 bits per second of digital information to be transmitted. The scientists field tested the system on Lianhua Lake in Heilongjiang, where two ships spaced 2 kilometers apart were able to reliably transmit information via these fake dolphin vocalizations. Hypothetically, even the most experienced sonar operator would, upon hearing these artificial dolphin sounds, dismiss them as naturally occurring animal noises, allowing for secret messages to be conveyed. So the next time you hear dolphin click sounds when swimming under water, this is what might be happening:

1) Dolphins echolocating

2) Navy submarines transmitting a secret coded message

3) Harland Williams filming Down Periscope 2

Here’s the article in question, which was recently published in the The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America:

Liu S, Qiao G, & Ismail A (2013). Covert underwater acoustic communication using dolphin sounds. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 133 (4) PMID: 23556695

Liu S, Qiao G, & Ismail A (2013). Covert underwater acoustic communication using dolphin sounds. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 133 (4) PMID: 23556695

March 18, 2013

Bizarre video footage of a dolphin exhaling air from her eye socket

In this bizarre video footage, a female Indo-Pacific dolphin is seen exhaling or leaking air from her left eye socket.

In case you might not be familiar with dolphin anatomy, dolphins aren’t meant to breathe through their eyes. In your traditional dolphin body, there is only one connection from the lungs to the outside world, and that’s via the blowhole. Everything in the dolphin’s skull is designed to make the transfer of air, in those brief moments when a dolphin’s head breaks the surface of the water, as safe and efficient as possible. Evolution even designed anatomical structures to block the connection from a dolphin’s mouth to its lungs just to make it that much harder to either accidentally inhale water, or inadvertently leak air. With such an exquisitely designed closed system, how can we explain this strange video footage?

A team of dolphin scientists, including dolphin cranial specialists (yes that’s a thing), analyzed the above video and concluded that there must be something quite abnormal – and rather sinister – happening in this poor dolphin’s head. Dolphins have a number of air sac and other air-filled structures in their skull, including a sinus-like structure adjacent to their eye sockets. In a normal dolphin, there is an air-tight barrier of blood vessels and fibrous muscle tissue that separates this sinus structure from the eye-socket, with just enough room to allow the ocular nerve to pass through en-route to the brain. This flexible tissue-wall expands and contracts as the dolphin’s nasal-sacs fill with air. But for the poor dolphin in this video, there is some sort of hole or leak in this tissue-wall, which causes the expanding air to rush into the eye-socket as the animal rises to the surface. How did this hole get there? Here are the scientists’ two best guesses:

1) A worm-like lung-parasite (i.e., a nematode) ate its way through the tissue-wall.

2) The barb from the tail of a stingray stabbed the dolphin in the eye and punctured the tissue-wall.

Either of those options are tragic and/or gross, not to mention uncomfortable. So will this dolphin die from this bizarre problem? Maybe not. The two biggest risks for this dolphin are that it can’t keep enough air in its lungs to stay under water long enough to find food, or that the hole might actually let water rush into its lungs if it dives too deep. I guess the main lesson here is that if you suspect you have lung nematodes and are planning a diving holiday this summer, please visit your physician to see if the nematodes have eaten a hole in your sinus tissues. Maybe that’s not really the main lesson. But it is a lesson.

You can read more about this situation in the original article:

Dudzinski, K. (2013). Short Note: Air Release from the Left Orbit of an Indo-Pacific Bottlenose Dolphin (Tursiops aduncus): Symptomatic and Anatomical Aspects Aquatic Mammals, 39 (1), 97-100 DOI: 10.1578/AM.39.1.2013.97

PDF at this link.

The video footage was filmed by John Anderson of Terramar Productions.

UPDATE:

I actually didn’t notice this until a reader pointed it out to me, but that guy in the video is reaching out to try to touch the dolphins. Not cool bro! It is strongly advised to not touch wild dolphins in these kinds of situations. No chasing, no feeding, no touching – just observe silently and try your hardest not to bother wild dolphins, kthanks!

March 15, 2013

Escaped killer dolphin story confirmed as bogus

The Russian news agency that first broke the story of escaped killer dolphins (RIA Novosti) has, as of this morning, run an article suggesting that the news story is entirely bogus. According to the report, Ukrainian military officials traveled to the State Oceanarium and saw the supposedly “escaped” dolphins with their own eyes. The director of the Oceanarium, Anatoly Gorbachyov, confirmed that the document sent to the media detailing the dolphin escape was a fake – and contained a badly forged version of his signature. The folks at the Oceanarium also state that the former Soviet military dolphins are not even being trained for military purposes at present, which I am inclined to believe given that 1) the only source suggesting that they’re being trained to kill people is the news agency RIA Novosti, which now has a dubious track-record of reporting on Ukrainian dolphin affairs, and 2) the State Oceanarium appears to be using these ex-military dolphins for therapy and recreational swim purposes. It seems unlikely that the same dolphins allegedly being trained to stab combat divers with face-knives are also letting toddlers ride around on their backs. And with this latest report, we can retire the riveting story of Ukrainian killer dolphins. It was fun while it lasted interwebs. But maybe from now on we’ll live by the motto “pics or it didn’t happen.” (and this pic does not count)

March 14, 2013

Escaped killer dolphins a hoax? Maybe, maybe not.

The killer Ukrainian dolphin story has now been declared a hoax by the media (e.g.,Salon, MSN, Outside). An initial news report from the Russian news agency RIA Novosti suggested that Ukrainian military dolphins, trained to attack enemy swimmers, swam away from their handlers and were roaming the Black Sea. This became an instant internet sensation, but was quickly followed by reports that the source of the information provided to RIA Novosti was a fake document forged by a disgruntled ex-employee and/or museum director. The Ukrainian military has denied the reports from the get-go.

The thing is, I have yet to see a news report that has been able to confirm that the source of the information suggesting that this whole incident is a hoax is any more credible than the source suggesting that the dolphins did in fact escape. Both sources are pretty darn sketchy. As many have pointed out, the idea that the Ukrainian military could have revived the ex-Soviet military dolphin program and is training their dolphins in anti-personnel tactics is entirely plausible, if totally unconfirmed. And captive dolphins do sometimes wander off. So the basis for the story is well within the realm of possibility.

What surprises me is that so many news outlets have been keen to report on this story based on nothing other than that single RIA Novosti news item and/or a handful of weird websites suggesting the story is a hoax. Surely what we really need is an intrepid journalist to make their way to Sevastapol, interview some of the people involved in this story, and perhaps count the number of dolphins with knives strapped to their heads to see if any are in fact missing? Or, to determine if dolphins have knives strapped to their heads.

Until such time as this happens, maybe we should take headlines like these with a grain of salt: ‘HEAVILY ARMED SEX CRAZED DOLPHINS on RAMPAGE in Black Sea,” or “Killer Dolphin Escape to Black Sea Story a Hoax, Reports Say.” Let’s see what the third act brings us, shall we?

UPDATE:

As of this morning (March 15th) RIA Novosti is now reporting that there are no killer dolphins on the loose. Indeed the documents initially provided to the media were a fake, and all the dolphins (which are probably not even being trained for military purposes in the first place) are safe and sound at the Ukrainian State Oceanarium. Third act now resolved. Roll credits.

March 13, 2013

Ukrainian killer dolphins – the saga continues

Yesterday’s story about killer Ukrainian dolphins on the loose appears to have gone viral, with a handful of news agencies and blogs citing my blog entry as the basis for the story (e.g., The Atlantic, BoingBoing). It’s fun to hear folks at the Huffington Post Live mention my name (even if tainted with sarcasm – “dolphin scientist” is a real thing people), or see screenshots of my blog as my words are quoted on air. It’s important to point out though that I had nothing to do with this story other than to re-post the information I found on the Russian news agency RIA Novosti’s website with added humor.

The Ukrainian military has denied the original reports by RIA Novosti that the dolphins did in fact escape. This Ukrainian news report from today seems to be suggesting (as far as I can tell from Google Translate) that the entire news report was based on false information, with RIA Novosti having received documents supposedly from military officials, but containing forged signatures, detailing a dolphin prison-break that never happened.

So are there killer dolphins on the loose or not? There is no clear answer at present. Perhaps journalists will make their way to Sevastapol and bring us back the real story. In the meantime, we can enjoy the many humorous images of killer dolphins that the interwebs have been generating:

Courtesy of Jenni Ryall from www.news.com.au

[image error]

UPDATE: This news story is confirmed as bogus. Read more here.