L.B. Joramo's Blog, page 7

September 4, 2013

Is History a Bigot?

They say history is written by the winners.

However, my favorite word while growing up was and still is, “No.” So, no, I don’t accept that as the truth.

Clio, the Muse of history

Lovely Clio is the Muse for historians. You can usually find her sitting around on plump pillows with a boob hanging out–because why not, you know?–and with paper, pen, and a trumpet or some sort of horn. Why the horn? Because she’s so eager to blast us with history. She wants all of us to know the past.

But does she want us to know only certain aspects of the past, for instance only the winner’s version of events? Does she whisper into the historian’s ear only what she wants us to know?

Psh. Of course not! Clio has long loved history, and wants to make every aspect of it famous. I know that, because that’s what her name means literally—to make famous or to celebrate. Clio has long wanted historians to rejoice ALL aspects of the past, and she’s ready to trumpet out whatever the historian has researched.

Wait! Whoa. Isn’t that revisionist history? And revisionist history is horrible, right?

Well, let’s break it down. What is revisionist history in the first place? Cristen Conger in her informative article, “How Revisionist History Works?” states that there are three perspectives of revisionist history:

Social or theoretical perspective to re-examine the past through different lenses

Fact-checking perspective to correct the record of past events

And negative perspective that views revisionism as an intentional effort to falsify or skew past events for specific motives.

It’s this last theory that has led many to believe that revisionist history is not real history. However, Ms. Conger points out rather elegantly that for hundreds of years there were whispers that Thomas Jefferson had had children with his slave, Sally Hemings. Until the 1990s this was considered a fowl rumor, but then by DNA evidence it was declared as truth. This is revisionist history at its best—discovering an unbiased truth.

Being a woman I am especially fond of revisionist history. Until after WWII, historians hardly noted that women were even in history. Yet somehow the human species propagated itself. Hmm . . . wonder how that happened? Well, because women were around! In my own research I’ve found that not only were women there, making clothes and food for the men, but they took part in battles. And not just cooking for soldiers. I’m not talking about Molly Pitcher here. I’m talking women, and there are multiple sources of this, have been fighting in battles for hundreds and hundreds of years.

Granted, revisionist history can be a bit jarring. When you think you know something, then are told you don’t, it’s not just frustrating, but sometimes it can lead to massive changes within one’s core values. But here’s the amazing thing about history, it is alive. Just stay with me for a moment, because some of you thought history was in the past, hence it’s dead, right? But with pursuing an unbiased truth—a more truth, as I call it—one can find that history changes. She opens her eyes and is only too glad that we’re finally discovering another layer to her mystery.

Lastly, if you aren’t too sure of something, take a cue from me. Just say, “Um, no.” Then look it up for yourself. Question everything, and Clio and myself will thank you for it.

August 29, 2013

The Revolution of the Publishing World

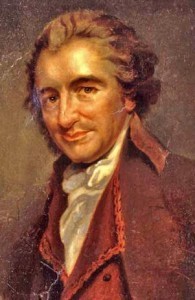

Thomas Paine nowadays is known as an American Forefather. And well he should be. It was thanks to his Common Sense published in January 1776 that ensured the Continental Army had enough recruits to continue the war. In the winter proceeding Paine’s bestseller, the Rebels had witnessed the tragedy of General Richard Montgomery and the national hero, then, Colonel Benedict Arnold’s defeat at Quebec that resulted in the loss of beloved General Montgomery. Before that, the Battle of Bunker Hill had been a terrible blow to the Rebel’s ego, even though they injured or killed forty percent of the redcoats. The commanding officer of the Continentals, General George Washington, was a man who wasn’t sure he was fit for his office, and many of his subordinates wondered the same. But worse, what had started out as bands of Massachusetts’ militias, was now many more militias from all the colonies, grouped together to make the most misfit army the world just might have ever seen. And that oddball army was threatening to go back to their homes at any minute. The rebellion appeared gloomy at best.

Thomas Paine nowadays is known as an American Forefather. And well he should be. It was thanks to his Common Sense published in January 1776 that ensured the Continental Army had enough recruits to continue the war. In the winter proceeding Paine’s bestseller, the Rebels had witnessed the tragedy of General Richard Montgomery and the national hero, then, Colonel Benedict Arnold’s defeat at Quebec that resulted in the loss of beloved General Montgomery. Before that, the Battle of Bunker Hill had been a terrible blow to the Rebel’s ego, even though they injured or killed forty percent of the redcoats. The commanding officer of the Continentals, General George Washington, was a man who wasn’t sure he was fit for his office, and many of his subordinates wondered the same. But worse, what had started out as bands of Massachusetts’ militias, was now many more militias from all the colonies, grouped together to make the most misfit army the world just might have ever seen. And that oddball army was threatening to go back to their homes at any minute. The rebellion appeared gloomy at best.

But then Thomas Paine’s Common Sense was published. It spread like brush fire, and before anyone knew what was happening, more boys and men (and women) came from all the thirteen colonies to enlist in the Continental Army, which was much needed since most enlistment terms ended that December 31, 1775. Without Common Sense the army might not have had enough men to continue fighting. Further, the Rebellion had more supporters from the large population of Americans who had previously been apathetic to the cause. Benefactors gave more money to the cause too. And unbeknownst to most at the time, France secretly gave money and arms to the rebellion before, but especially after Paine’s release.

Of course many historians think this merely coincidence that France gave when she did. But one can’t help but notice the timeline. Paine’s Common Sense spread throughout Europe as well as America, and it was after some agents of Louis XVI had read Paine’s work that the arms, that had already been clandestinely planned to arrive in America, came quicker (see Paul for more on the French covert affairs). Happenstance or not, the arrival of much needed gunpowder and arms from France could have been the magical pull of Paine. The world may never know.

By the summer of 1776, on July 9th, when Washington ordered the Declaration of Independence read to all his troops, things appeared to going well for the Rebels. Much of that is because of Thomas Paine’s influence through Common Sense—a piece about justice.

Paine’s influence over the American and French Revolutions (although sometime in the future we need to discuss if the American Revolution was truly a revolution or not) is well known and documented. What many don’t know is how Paine revolutionized the world of publishing. In Paine’s day, as Michael Everton explains, a writer would not have expected recompense from his publisher.

Until the rise of the mass market for books in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, book publishing was a simple cottage industry. An author would approach a bookseller-printer – these two roles were not yet differentiated – and contract for the printing and selling of his book. Frequently the costs were borne, wholly or in part, by a patron of the author, who thus ensured that the book would reach its intended audience among the cultural and social elite of the day.

Royalties were unheard of in Paine’s time. But that’s what he asked of his first publisher, Robert Bell. Paine approached Bell with the deal that they both would make fifty percent of the profits, after initial costs were paid.

Bell probably never thought that he was publishing the first American bestseller, Common Sense. “We know that Paine was fairly accurate when he estimated that 120,000 copies had been sold in 1776 alone. Yet historians estimate that as many as five times that number actually read the book (or heard it read) – one-fifth the adult colonial population” (Everton). Bell made a huge profit from the pamphlet.

When Paine came to Bell, asking for his share of the money, Bell, at first, said there was no income. Then Bell began to change his tune, for he’d made a fortune from Common Sense. But Bell, being the publisher of his time, thought he was entitled to all of it. Although there had been the hubbub of the Statute of Anne of 1710—a copyright law, never was there word that an author could actually make money off his writing—royalty pay.

But Paine had struck a deal with Bell, and being the kind of man who doggedly pursued justice, he took matters into his own hands. He went to a different publisher with a second edition of Common Sense and began to post in newspapers less than glowing reviews of Bell. Bell wrote his own newspaper articles about having the liberty to take all the profit from Common Sense, for what we modern readers think of as piracy of books, was status quo for the eighteenth century publisher. Piracy, plagiarism, and unrequested reprinting of books were the norm—just ask Benjamin Franklin. Bell thought he had a right to all the money; it was his liberty to do so. However, Paine thought of Bell as the equivalent of, who he called, tyrannical King George III and the British Parliament. In the end, Bell might have done better, if he had realized whom he was up against. He was fighting the first bestselling author of America. He was fighting a losing battle.

When the dust settled between Paine and Bell, Paine couldn’t get all his money from Bell, but that seemed all right with him. More than the profits, he made a statement to all Americans and writers from there on out: Writers had a right to make money from their work.

What do you think of Paine’s Publishing Revolution? Do you think writers deserve to be paid? Let me know your opinion please.

Works Cited

Everton, Michael. “’The would-be-Author and the Real Bookseller’: Thomas Paine and

Eighteenth-Century Printing Ethics.” Early American Literature 40.1 (2005): 79-

110. ProQuest. Web. 14 June 2013.

Paul, Joel Richard. Unlikely Allies: How a Merchant, a Playwright, and a Spy Saved the

American Revolution. New York: Penguin Books, 2009.

June 12, 2013

And They Lived Not So Happily Ever After . . . Really?

I have for a number of years managed to have my academic life remain in one corner of my brain, while my creative life remain in another. Certainly my academic research has been fodder for my creative mind from the very beginning. Anything I learn, takes on a life of it’s own in my brain, but all in all it’s been very polite for quite a while. Until lately.

Corners of my brain fighting

Now I can’t seem to stop myself from venting my endless opinions. In my academic writing! Yes, much of the world of academia is opinions, but I do research. And, yes, some of my research does need opinions, but there is a certain way to format one’s opinions in an academic piece. Yet for the life of me, I can’t seem to do it anymore.

And here is where I slipped: I read through an educational website about women in the eighteenth century, although, it could relate to women in the nineteenth century too. It’s a well researched website that is interactive, which makes it a bit fun too. When I was done playing with the website, I was asked the question that seemed to turn off my academic mind completely. “What other kind of ending can you envision for an eighteenth century woman?”

So now, I’d like all my writing friends to complete the question at hand too. Please go to the website, http://www.umich.edu/~ece/student_pro..., and play around, see what kind of ending you end up with, but more than that I would love to see just how many of you could write me a different scenario—perhaps a happy ending, please?

Leave as long as a comment as you want! Or just give me a quick note. Either way, maybe I could appease the creative side of me, and finally get my academic side of me back.

Oh, and by the way, perhaps why this bothers me so much is because in my historical release, The Immortal American, I did write my eighteenth century heroine a very different ending that what the website recommended. If you’d like to know more about my book (hopelessly plugging my book again—yeesh!) please go to Amazon.

June 5, 2013

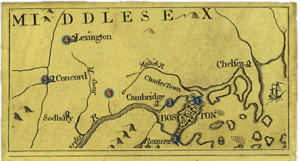

The Shot Heard ‘Round the World – Lexington and Concord and the Start of the American Revolution

Please help me in welcoming Dr. Stanley Carpenter. Below is his article about the battle that started not only the American Revolutionary War, but my book, the Battle of Lexington-Concord. Yes, I’m hopelessly plugging my book. But just bear with me please. Violet, my protagonist, not only witnesses the shootout at the Old North Bridge, but eventually grabs her own musket and participates. So this article is one that I’m very grateful to add to my blog, but also to read over and understand just where some myths come from, and how some mysteries of that war will never be solved. So without further ado . . . here is a snapshot of the Battle of Lexington-Concord by Dr. Carpenter!

The Shot Heard ‘Round the World – Lexington and Concord and the Start of the American Revolution

Prof. Stanley D.M. Carpenter, US Naval War College

Faced with the threat of potential violence from the increasingly hostile local population, Major-General Thomas Gage, Crown Commander-in-Chief in North America, having received reliable intelligence that the local Massachusetts Bay militia groups known as “training bands” had gathered and stored arms, powder, and other weaponry in Concord, Massachusetts (northeast of Boston), ordered Lieutenant-Colonel Francis Smith to march 700 troops from Boston on the morning of 19 April 1775 to capture or destroy the military supplies.

At 0300, Smith sent Major John Pitcairn ahead at a quick march with six companies of Light Infantry, which arrived at Lexington Commons about sunrise. Set in motion by instructions received 14 April 1775 from Secretary of State for the Americas, the Earl of Dartmouth, to disarm rebels and arrest leaders after a series of largely bloodless clashes called the “Powder Alarms,” Gage resolved to take positive action. But, from agents in London, the colonists already knew of the orders and, alerted the night before of the British movements by fast riders, the militia started to gather.

As the first three companies of Light Infantry arrived on Lexington Commons and formed up (with the main body still down the road towards Cambridge) seventy-seven Lexington militiaman commanded by Captain John Parker exited Buckman Tavern and lined up on the Commons. Legend has it that Parker exclaimed to his men: “Stand your ground: don’t fire unless fired upon, but if they mean to have a war, let it begin here.” Either Pitcairn or another officer rode forward and ordered the colonials to disperse, shouting “lay down your arms, you damned rebels.” Although Parker then ordered his men to stand down, none laid down their arms. Both Pitcairn and Parker ordered their men to hold their fire, but a single shot set in motion the ensuing chaos. Various theories abound, including a shot from the second floor of Buckman Tavern or from behind a hedge or from a mounted British officer, possible Pitcairn. Sporadic firing erupted from both sides. As the British troops advanced with bayonets, the militiamen fled. One soldier of the 10th Regiment of Foot suffered a slight would, but eight militiamen died in the melee with a further ten wounded.

Hearing the gunfire, Smith hurriedly rode forward. With the beating of Assembly, he re-organized his column and marched northwest towards Concord. As the regulars approached Concord, roughly 250 militiamen formed up to block the passage; realizing the numbers disparity, the militia under Colonel James Barrett abandoned the town and retreated to the Old North Bridge a mile from Concord as militia from more westerly towns started to arrive.

In town, the Grenadiers of the 10th Regiment secured the South Bridge while the Light Infantry occupied North Bridge as the troops began a thorough search for arms. Amazingly, the regulars found three 24-pounder cannon buried at Ephraim Jones’ Tavern. The soldiers smashed the gun carriages and tossed 550 pounds of lead musket balls into a millpond. Troops paid for the food and drinks from the locals even while they were being misdirected as to the location of additional arms and powder. Tragically, a fire set to burn additional gun carriages set afire the town Meeting House and the soldiers formed a bucket brigade. Seeing the smoke, Barrett’s men hurried back towards Concord and established a position near the North Bridge as militiamen from Acton, Concord, Bedford and Lincoln arrived.

Severely outnumbered, the troops holding the North Bridge fell back with militia in pursuit. Captain Laurie formed the two Light Companies into ranks to defend the bridge, but sporadic firing broke out from both sides as officers and non-commissioned officers sought to restore order and discipline.

On the militia side, Barrett regained control and moved his men 300 yards back up the hillside as Smith assembled two companies of Grenadiers to reinforce Captain Laurie. Meanwhile those soldiers that had searched Barrett’s farm returned and the firing ceased. The soldiers, watched carefully by the militia, completed the search, ate lunch, and formed up for the march back to Boston with their mission completed. But, as the formation moved across the Bridge, Reading militiamen opened fire. With ammunition low and many officers, including Lieutenant-Colonel Smith (wounded in the thigh) felled by the musketry, the march back became a nightmare for the relatively inexperienced British soldiers. Many casualties occurred as the militiamen in a running battle, fired from behind stone fences and trees, thus originating the mythology of colonials firing from behind rocks and trees at marching formations on the road. This type of action occurred only once in the ensuing war – at the march back from Concord.

By early afternoon, a 1,000-man relief column under General, the Earl of Percy arrived with several Regimental Battalion Companies. They encountered Smith’s Grenadiers and Lights, who appeared disorganized, ragged and dazed. Percy opened fire with artillery that dispersed the militia. He set up a hasty field hospital at the Munroe tavern to treat the wounded and after a brief pause, began the march back to Boston. The “run and gun” engagement continued once the artillery ceased fire. With flankers out to disrupt snipers and wagons carrying wounded in the center of the column, the march to Boston encountered a number of small skirmishers. With far greater numbers, the rebels lined the route of march to snipe at the retiring British troops. As the column reached Menotomy, house to house street fighting broke out as soldiers flushed out snipers posted in homes and commercial buildings.

By evening the battered British force reached the safety of Boston, but with heavy casualties. As many as 15,000 colonial militia had taken part in the engagements with forty-nine killed, thirty-nine wounded and five missing, presumed dead. On the Crown side, seventy-nine British soldiers died with 174 wounded and over fifty missing, presumed dead. The actions at Lexington and Concord sparked off an active and violent rebellion that only ended with the surrender at Yorktown, Virginia of Lieutenant-General Charles, Earl Cornwallis in October, 1781 to the Combined Franco-American armies. The actions at Lexington and Concord on 19 April 1775 prompted George Washington to exclaim that the “once happy and peaceful plains of America are either to be drenched in blood or inhabited by slaves. Sad alternative! But can a virtuous man hesitate in his choice.”

April 30, 2013

Welcome to the Salon & The Rumblings of Rebellion

We are in the midst of spring, summer is yet to come, and the weather is finally turning warmer, for those of us in the northern part of the Northern Hemisphere. It’s such a promising time!

For my blog, I’ve recently had a discussion with a friend (Thanks, Rayne!) as to my intentions. I always wanted this to be a place where history could come alive, and people could come here to discuss the events that happened during the American Revolution. But now I want to open the doors to not just the events, but also the philosophy, the sociological ramifications, the anthropological understandings of much of the eighteenth century, and art, music, you name it! And to have a better understanding, we might converse about Greek history, the Medieval era, Jacobite uprisings, or other times and occasions, as well as we could touch on delicate subjects that still affect us today. I will still have my wonderful academic friends come to write articles, and I will include many historical writers (fiction and non-fiction) who will share their knowledge and their brilliant books! This will be a place to laugh, maybe cry a little, but always to think. In short, my blog will become an eighteenth century salon. Something that Benjamin Franklin would want to visit, to talk at length of matters, play with ideas, and to become Enlightened people. (I meant that pun, yes.)

The blog might change in its settings, to reflect more of a salon atmosphere. So I hope you don’t mind the “construction” that it will go under, but your ideas and thoughts are always welcome here!

Today, we will continue with the audacious American colonists and equally daring British Parliament. The Stamp Act had just been repealed by the Parliament, yet in its place was the slippery Declaratory Act of 1766. At first no one seemed to notice the Declaratory Act. Most Britons and Americans alike were simply overjoyed with the fact that the Stamp Act was no more. No American, especially, took heed of the language of the Declaratory Act: “The Parliament of Great Britain had, hath, and by right ought to have full power and authority to make laws and statues of sufficient force and validity to bind the Colonies and people of America in all cases whatsoever.” In other words, Parliament had a right to tax the colonies if it so chose, even without sufficient representation.

Keep in mind, that most Americans didn’t observe the Declaratory Act as much of anything other than a device to save Parliamentary face. You see, because the Americans had rioted, rebelled, and boycotted, they thought, they had stopped the Stamp Act. The fact that the American colonists considered that they had gotten their way through rebellion is particularly important to note.

So after the Declaratory Act everything was hunky-dory for both the British Parliament and the American colonists, until the Quartering Act.

To better explain the Quartering Act, let’s go back to the French and Indian War (The Seven Years’ War.) After that gigantic and costly war, the Regulars—AKA the redcoats, British’s standing Army, were needed to remain in the American colonies. Why? For a number of reasons: 1.) The redcoats needed to be there to keep the peace. There were many colonists and a few Native American tribes who had sided with the French, and after their loss, there were quite a few land grabs as well as outright slaughter. 2.) Although France had signed the Paris Treaty of Peace, that did not mean they were not ready to strike back in less outright ways at the British. The redcoats had to be stationed at New York, especially, to make sure no French spies had too much information, as well as France could not trade with the American colonies. And the final reason mentioned here, but definitely not the last, was 3.) The Regulars needed to be stationed in the frontiers to ensure that American colonists would not cross the Proclamation Line, the boundary that ensured that many Native American tribes had their own territory. With the unflattering name of the French and Indian War, it is assumed that all Native Americans sided with the French, but the Proclamation Line helped the many tribes who allied themselves with the British during that war.

So back to the Quartering Act of 1766, which ordered the American colonists to “provide barracks and supplies such as candles, fuel, vinegar, beer, and salt for the Regulars.” This was considered as “another form of internal taxation.” And this was a very big no-no for the Americans. They began to call Parliament tyrannical again, and they knew there was one way to make Parliament stop.

Do you know what the American colonists did next? Do you wonder why we Americans call the French Indian War such, instead of the Seven Years’ War, like most of the world? Do you think Parliament could have done something different, other than instate the Quartering Act? I mean, after all the Regulars were there, on American soil, FOR the Americans. Why not have the American colonists help pay for their own defense? Do you think the Americans were complaining too much? Do you think Americans today would do the same?

April 24, 2013

War and Women Soldiers

When I first began researching the American Revolution one of the first people I researched was Deborah Sam[p]son. She fought as a Continental Soldier during that war. She disguised herself for many months, was shot twice, but the last shot she got an infection, a fever, and had to be rid of her clothing to cool her off. It was then that her gender was discovered. There is much controversy over what happened after her life, but the facts are that she had help to write her memoirs, which may or may not be very accurate, she gave tours to promote her book, and she did have a pension that was granted to her for her time served with the military.

Women fighting during wars have long interested me. And I’m not the only one. Susan Macatee writes about women who fought during the Civil War. She’s done extensive research in this area, so I’d like all of you to please give Ms. Macatee a warm welcome as she discusses women fighting during the Civil War.

Women Soldiers in American Civil War Armies

Although we have had women participate in wars throughout history, the fact that women served as soldiers during the American Civil War was never recorded in any history book. After all, the 1860s was the height of the Victorian era, where women, at least high and middle class ones, were thought to be delicate creatures, needing to be cared for and protected by their men folk. The idea of a woman charging into battle, firing on the enemy or worse, yet, being wounded or killed was unimaginable.

Even women who nursed wounded soldiers were often frowned upon by polite society. But in the book, All the Daring of the Soldier, by Elizabeth D. Leonard or An Uncommon Soldier, by Lauren Cook Burgess, these real life women warriors are finally exposed for the true heroines they were.

Women weren’t allowed to join either army during the American Civil War, but according to Leonard, many young women were driven not only by “Patriotism and the love of a good man…” but also by “…their quest for adventure and their hope for a different sort of paying job than was typically available to them.”

As part of my research for my 2009 release, Confederate Rose, I came across An Uncommon Soldier.

The book tells the story of Sarah Rosetta Wakeman through letters she sent home to her family that fortunately, her family preserved over the years.

What’s unique about Sarah’s story is, like scores of other young women during the American Civil War, she disguised herself as a man and served in the Union Army as a private. And during the years she served, no one ever discovered her sex.

Many other women also enlisted in male disguise, since women at that time weren’t permitted to serve, but some were quickly discovered and either sent home or were arrested and sent to prison on false charges of prostitution. That was the only reason army officials could come up with for women to dress as men, although it would have been hard for them to ply their trade and not be found out. Others weren’t caught until they were hospitalized or killed in battle. But many served out their time and returned to civilian life without ever having been discovered.

Sarah was born on January 16,1843, the eldest in a fairly large farm family. She was used to hard work and in 1862, at the age of 19, with no prospects for marriage, she left home to seek outside work to help with the family finances, including a large debt owed by her father. Disguising herself as a man, she found work as a manual laborer on a coal barge for $20.00 for four trips up the Chenango Canal in New York State. On her first trip she encountered soldiers from the 153rd New York Regiment, who urged her to sign up. The enlistment bounty of $152.00 would have been more than a year’s wages, even if Sarah continued civilian work as a male, and so was a great enticement.

Sarah told the recruiters she was 21 and on August 30, 1862, signed up under the name of Lyons Wakeman. Her regiment was stationed in Washington, as one of many, to guard the Capital from the surrounding hostile territory.

In her frequent letters home, she asked her family not to be ashamed of her for the choices she’d made. She also sent money home on a regular basis, much more than she could have earned as a civilian. In February 1864, the regiment was transferred to the field to take part in the ill-fated Red River Campaign. By the end of the campaign, Sarah developed chronic diarrhea and ended up at a regimental hospital.

She died on June 19, 1864, never having been discovered.

Like Sarah, most of the women who disguised themselves as men to serve in the army were lower class, or immigrants, who had little education. Sarah is unique, however, in that she could read and write and, as a result, left her legacy of letters so we’d have the opportunity to see why a woman would choose to hide her identity to serve her country.

For more information on Sarah Rosetta Wakeman, read An Uncommon Soldier, by Lauren Cook Burgess, Oxford University Press, ISBN-0-19-512043-6

And for more stories of women soldiers and spies, read All The Daring of the Soldier by Elizabeth D. Leonard.

My romance novel, Confederate Rose, as well as my new novella, The Christmas Ball, feature women soldier heroines. For more information on my romances, visit my website http://susanmacatee.com

Susan Macatee writes American Civil War romance, some with a paranormal twist. From time travels to vampire tales, her stories are always full of love and adventure.

She’s spent many years as a Civil War civilian reenactor with the 28th Pennsylvania Volunteer Regiment. She’s a wife, mother of three grown sons, and has recently become a grandmother. She spends her free time inhaling books and watching baseball games and favorite old movies.

Confederate Rose available at Amazon http://www.amazon.com/Confederate-Ros...

Barnes and Noble http://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/confe...

The Wild Rose Press http://www.wildrosepublishing.com/mai...

and All Romance Ebooks http://www.allromanceebooks.com/produ...

The Christmas Ball available from The Wild Rose Press http://www.wildrosepublishing.com/mai...

Amazon http://www.amazon.com/The-Christmas-B...

Barnes and Noble http://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/the-c...

and All Romance Ebooks https://www.allromanceebooks.com/prod...

April 18, 2013

Celebration time, Come On! My book is FREE today!

Today is the DAY! Today is the beginning of my party to help celebrate my book, THE IMMORTAL AMERCIAN! For two days I’m going to rejoice, and to mark these special days I’m giving my book away! It’s free, the electronic version, today and tomorrow, April 19 – 20!

Since this is my party, and I LOVE costume/masquerade parties, I’m inviting all of you to virtually wear any kind of costume/masquerade you’d like! Please leave a comment either telling me about what you’re wearing or showing me by inserting a picture. On Sunday my son will pick his favorite costume, and the winner will get a $25 Amazon gift card! For me, I’m not part of the drawing for the gift card, but I have to “dress up” too. So, since I’ve been researching the American Revolutionary War from the British point of view for the last few months, I am going to wear red, lots of red! My redcoat costume will be complete with my trihorned hat, a Brown Bess Musket with bayonet, and this dress . . .  Like it?

Like it?

Unfortunately, one of my favorite historians was to write a piece for today, but, you know, things come up. He is to discuss the Battle of Lexington-Concord, and because I do expect his piece to come in soon, I won’t write much about it. But today marks the 238th anniversary of that battle, and the beginning of the American Revolution. In short a little more than 800 redcoats marched through the Massachusetts countryside and although they were supposed travel right through the village of Lexington for Concord, that didn’t happen. To this day we don’t know who really fired off that first shot in the very early morning hours at Lexington’s Commons, although many historians believe it was a colonist perched in a tavern. Within just a few minutes there were eight Lexington men dead and ten injured, and word spread of the American casualties faster than the redcoats could march. By the time the 800 British soldiers entered Concord there were hundreds of militiamen from all over Massachusetts pouring in to help in any way possible. Then there was a standoff over the Old North Bridge, this time we believe the British Army shot first. The militiamen returned volley. The standoff didn’t last long, as the redcoats retreated to the Concord Commons. They treated their wounded, recouped, then began to march back to Boston. After a little more than a mile into the redcoats’ march, the militiamen retaliated and began to shoot at the rows of red-clad soldiers. The Massachusetts men continually tried to ambush the redcoats, while they ran back for Boston. It was back at the village of Lexington that a little more than 1,000 British relief soldiers fired at the militia, to force them to stop the ambush. It worked for an hour or a little more, then the British soldiers were on the move, and the Massachusetts militia was too. The firing at each other continued and escalated until the village of Menotomy, now called Arlington. The fighting was fierce at that village, but the redcoats marched on, the militia on their heels. By the time the British reached Charlestown, it was growing dark, and the militia backed off. On the morning of the 20th the British Army was surrounded by Massachusetts militia and other New England militias were marching in by the hundreds. It was the beginning of a siege and so much more to come.

This battle also is a major pain in the butt for my protagonist, Violet, in THE IMMORTAL AMERICAN. To read an excerpt of the book, check it out at Amazon or on my website, www.lbjoramo.com

April 17, 2013

British Debt and the American Revolution

I’d like to introduce Claudia Alexander to my blog! I’m so honored she could write for me here! As you’ll read in her bio below, she works with NASA. Not only does she get to use the cliché she’s as smart as a rocket scientist literally, but she is well versed in American Revolutionary History. Her article here is an eloquent piece about how national debt played the largest role in the American Revolution. Please welcome Ms. Alexander and read her insightful post!

A quick note before you do: In two more days my book THE IMMORTAL AMERICAN will have a huge virtual release party here on my blog!!!! I am having a favorite historian of mine writing a small piece about the Battle of Lexington-Concord, which would have happened 238 years ago that day, and it is the mark of the beginning of the American Revolution. I’d like you all to join me this Friday too, to celebrate our American heritage, and if you aren’t American I’d like you to come too! All re-enactors are welcome, even if you are in virtual costumes! And the best costume will win a gift card!!!! That’s right, even if your redcoat uniform or colonial homespun breeches are imaginary, just tell me what you are pretending or in reality wearing, and you could win a gift card!

Now here’s Ms. Alexander . . .

In a previous blog on this site, the question was asked, are the events that launched the country into the Revolutionary War still relevant to Americans today? My answer, looking at the subsequent 200 years of the country, has to do with the seesaw between political initiatives born out of poverty, the growth of plutocrats, financial crashes, and the words of our founding fathers regarding influence of the bank(ers).

We seem to collapse the emergence of Early Modern England & its battles with colonial America down to small moments, like the Boston Tea Party, as if the revolution were about tea and/or a bunch of meaningless (to a contemporary audience) Acts of Parliament that encroached on the colonies’ ability to manage themselves. Just read the Wikipedia account of the Revolutionary War, for starters, in which it was the Stamp Act that led to revolution.

The larger context has to do with the economy – that is, with recovery from war (and/or financial speculation), and a dynamic between a countries elites (whether Britain, or in America) and its working class. Sound familiar?

For reference, the Bank of England was chartered in 1694, and by 1750, according to some observers, English landowners emerged as a unified elite, confident in their position as a body of “natural rulers.”

But the French & Indian War devastated the British financial system. So Parliament shifted the tax burden to the British people. When the supply of money shrank, and normal people could not pay their bills, or obtain the credit required to purchase seed, for example, unemployment, poverty, and hunger ensued.

As ambassador to England in 1764, Benjamin Franklin observed the situation first-hand. When he arrived, he was surprised to find rampant unemployment and poverty among the British working classes. When asked how American colonies collected enough money to support their poor houses (where authorities threw people who couldn’t pay their bills), Franklin reportedly replied “We have no poor houses in the Colonies; and if we had some, there would be nobody to put in them, since there is, in the Colonies, not a single unemployed person, neither beggars nor tramps.”

Just a few years later, the British tried the same thing with the colonies, namely shifting their tax burdens to the colonies. They empowered British banks by taking away colonial ability to print their own money. Then suddenly poverty, destitution, and ruin were visited upon the colonial population.

That’s why the whole ‘Taxation without Representation’ meme. “…the colonies would gladly have borne the little tax on tea and other matters had it not been that England took away from the colonies their money, which created unemployment and dissatisfaction.” B. Franklin.

“[It was] the poverty caused by the bad influence of the English bankers on the Parliament which has caused in the colonies hatred of the English and . . . the Revolutionary War.”

- Benjamin Franklin

“There are two ways to conquer and enslave a nation. One is by the sword. The other is by debt.”

- John Adams

“All the perplexities, confusion and distress in America arise, not from want of virtue, so much as from the downright ignorance of the nature of coin, credit and circulation.”

- John Adams

Skip ahead a few years and we have other banking crisis in our history that resulted in widespread unemployment: 1837 (speculative lending practices), 1873s (war speculation + foreign currency debt); the 1920s (banking collapse); the 1970s (inflation + stock market crash + war speculation); 2008 (speculative lending practices). Each of these followed by a certain re-trenching of established financial interests.

Following the revolutionary war, in 1815, Madison himself created a national bank that “would attach the commercial part of the community in a much greater degree to the Government [and] interest them in its operations [emphasis added]…This is the great essential objective of our system…” [creating a national money & finance infrastructure]

Banking crash – 1837 – The Bank of the United States, now no longer attached to government, but private, and seen as conferring economic privilege on the social elites, is fought by Andrew Jackson in ‘The Bank Wars.’

Banking crash – 1929 & new regulations – FDR in a letter “The real truth of the matter is, as you and I know, that a financial element in the larger centers has owned the Government ever since the days of Andrew Jackson …The country is going through a repetition of Jackson’s fight with the Bank of the United — only on a far bigger and broader basis.” – FDR

Following the New Deal, bankers and industrialists such as Du Pont (Monsanto), used money to educate their peers & the masses to create the political change they would need to circumvent the New Deal.

It seems to be a repeating pattern.

In the words of Thomas Jefferson: “I believe that banking institutions are more dangerous to our liberties than standing armies …. If the American people ever allow the banks to control issuance of their currency, first by inflation and then by deflation, the banks and corporations that grow up around them will deprive the people of all property.”

So in our day, as we turn on the news and see details of a sequester, of congress that cannot agree on a budget because of powerful interests promoting smaller regulations [smaller government], of a nation emerging from war & financial speculation, the Revolutionary War, even without King George, is just as relevant as ever.

I’m not trying to suggest here that the founding fathers were against debt per se – rather it’s about the ability of first 13 colonies, then America and the 50 states to create its own credit, without owing interest, or loose that process to private bankers & their representatives (such as King George or in contemporary times banks that are ‘too big to fail’).

Bio: Claudia Alexander takes an avid, amateur view of American history. Her professional love is the planets, and she flies spacecraft by day, at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. By night she re-imagines the universe with fiction writing. The first of her STEM education, science-learning book series for kids ages 8-10, titled Windows to Adventure, will launch in July 2013. Aside from children’s chapter learning books, she has written a number of steampunk (retro-futuristic) short stories, and a full length elf-punk novel. Follow her on twitter at @claudiauthorsci, @Windows2Adventr & @redphoenixbooks

further reading:

The Currency Act (1751 & 1764): http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Currency...

The Revolutionary War & Beyond (B. Franklin’s observations in England prior to the war): http://www.revolutionary-war-and-beyo...

The Emergence of a Ruling Order: Landed Elite 1650-1750 by James M. Rosenheim

Invisible Hands by Kim Philips-Fein

Web of Debt by Ellen Hodgson Brown http://amzn.com/0979560802

April 10, 2013

American Dreams

In nine days I’m having my virtual party for the release of my book, but it’s already out. (Check it out here.) With all the planning for a blog tour and setting up book club parties, and everything that goes into promoting, I’ve been a wee bit overwhelmed. I know we were talking about the Declaratory Act and the happenings before the American Revolution, and I’ll get back to that, but I’ve taken a bit of philosophical journey. In my last blog I wondered if the American Revolution was relevant any more. And to tell you the truth, I do still wonder this question. It happened a little more than 230 years ago when men wore wigs, women were in corsets, and letter writing was Pulitzer Prize winning stuff. What do those people have in common with us?

In short I’ve come to realize that they wanted the same things we do, even today. They wanted to feel safe; they wanted a better life not just for themselves, but for their children too. These are immortal themes—the pursuit of happiness. But not just that, the revolution speaks to all of us, because it boldly says that all of us, each one of us—women and men alike, have the right to our happiness, and to seek it out in all avenues, and that we shall not be hampered by others in our dreams.

Dreams are a thread in our American tapestry. We dream big. We dream before our times. We dream of freedom and passion. We dreamed that one day our children would be able to play together, no matter their heritage or the color of their skin; we dreamed of landing men on the moon; we dreamed of outrageous peace through all of this. As a student of warfare, this last dream seems the most spectacular and beautiful to me.

I had a dream to write. Actually, I’ve done that all my life. When I was six I pasted together construction paper with my colorings inside, just so I could have my first book. But I had the audacious dream to write and make money at it. The very day my book was available on Amazon someone bought it. Already my dream has come true! Maybe now I’ll be more specific about how much money I’d like to make, but for now I’m just relishing in dreaming big, the American way.

How do you relate to your American history? Or do you? What are some of your dreams? Have you achieved them? If you haven’t or if you have, I want to know. Please share with me news of your latest release—post links too, so we can buy your book. Or maybe you’d like to share the first time you wrote something you knew to be brilliant, or anything else. It needs to be celebrated, and here is the place to do that!

Happy dance time!

April 3, 2013

Are the happenings of the American Revolution relevant anymore?

So, we were discussing the Declaratory Act, and I won’t leave you hanging—I’ll get to it in just a second, but I feel I should warn you, this post might not be what you’d imagined it would. Yes, well, the Declaratory Act passed by Parliament “stated that, ‘The Parliament of Great Britain had, hath, and by right ought to have full power and authority to make laws and statutes of sufficient force and validity to bind the Colonies and People of America in all Cases whatsoever.” (THE MARCH OF FOLLY, 165) In other words Parliament was saying to its colonies that they did have the right to tax, even their satellite lands, if they chose. And we all know that they did choose as much.

This brings up an interesting discussion: Because of this act, Parliament washed its hands of any wrongdoing, or wrong taxation without representation, as the case may be during the American Revolution. But was this a lawful act? It was passed unanimously. So the Parliament thought so at the time, and remember, this is the same Parliament who held about half its members as being sympathetic to the American outrage of being taxed without representation. So again I’ll ask, was this a lawful act? In technical terms, yes, because Parliament passed it, but it also went against the British Constitution and the Magna Charta. In philosophical terms the Magna Charta ensured that the people of Britain had rights from their king becoming tyrannical, as well as the king had a right not to be stormed and killed by the people, as long as he was doing what he was supposed to do. A king was not just supposed to rule his people, but to listen to them, and do what was best for the majority. The British Monarchy, from the very beginning in England’s King Alfred, had a thread of this philosophy: that the king could not be a dictator king, but listen to his people, which led to the Constitutional Monarchy we see now.

But does any of this matter anymore? Does it matter that our American history began with King Alfred and the Magna Charta and the British Constitution? Or should we just steer clear of all our British history? Only embracing what happened on American soil?

I ask these tough questions because this last week has been a bit of a rocky one, one of those weeks where I’m shaken to my very core, and wonder about myself. Oh, nothing horrible happened. So don’t worry about that, but something did happen that made me wonder about my values, my desires in life, and who exactly I am. I like to do this from time to time. Like, isn’t the word I should use, because when I go through these moments where I need to question everything, I’m a mess. But in the end, I know I’ll feel stronger about who I really am.

Since I’ve been researching the American Revolution, not only for my series but also for my Master’s Degree, I’ve felt uprooted a number of times. Things I had thought were part of American history were myths; other events that I thought were tyrannical were maybe not. For instance, the Declaratory Act makes it so that Parliament could further tax the American Colonies without being called tyrannical. Besides, Benjamin Franklin and other American colonists’ were always talking to members of the Parliament, and some people called this a “virtual representation,” which meant that America was in fact represented in Parliament. But were they? Was America being treated fairly after all? Were Americans too greedy? After all they enjoyed calling themselves Englishmen, and having the same rights of English people. Why not simply give in and pay what was due them? And after the Declaratory Act soon enough the Townshend Duties, or Act as many like to call it, were legislated as well. The Townshend Duties just needed revenue for the colonies’ defense. So why shouldn’t the American Colonies pay for it?

I’m not being ironic when I ask this. I simply want you to think outside of what is comfortable and what we think we know to be true. I’m asking you to do something that most people don’t like to do, but what might make you stronger. Dig deep and ask yourself, Was Parliament out of line when they passed the Townshend Act? Shouldn’t Americans pay for their own defense?

I hope I may not sway you, but I feel it necessary to answer too. In a very simple and elegant word, no. Why not? Because we were English people, who had certain rights and liberties. Benjamin Franklin and the other colonists in London, trying to speak for the colonists, were not elected officials, therefore, not proper representatives. Even with the passing of the Declaratory Act, it was still not acceptable to pass the Townshend Act, because the Declaratory Act was unconstitutional. No wonder everything in America went ape sh$* afterwards.

Now your turn. I’ve talked long enough, so now I need to hear from you. Do you think Parliament was fair in dealing with Americans? What do you think of this term rights? Or liberties? What do you think about virtual representation? And most importantly does any of it matter anymore? Is the happenings of the American Revolution relevant anymore?