Mark Fuller Dillon's Blog, page 6

December 5, 2023

Certain Joys

Between the Scylla of Netanyahu's genocide and the Charybdis of Western collapse in the face of challenges that our corporate-owned governments cannot confront, these are terrible days.

Only two things give me pleasure, now: music, and bringing to light illustrations from the past. Certain joys deserve to live.John Schoenherr. Cemetery World.

November 30, 2023

"The Mechanical Theatre of Sebastian von Schwenenfeld," by Jason E. Rolfe

Click for a better jpeg.

Click for a better jpeg.Jason E. Rolfe has long been one of Canada's best-kept secrets, and for years, now, I have loved the melancholic wit, charm, and laughter of his short story collections.

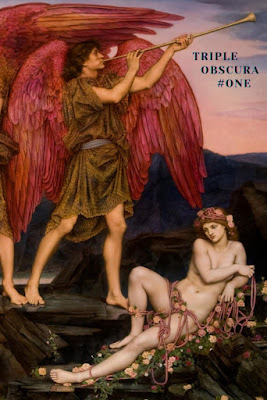

TRIPLE OBSCURA ONE, a recent anthology from Gibbon Moon Books, reprints a few of these Jason E. Rolfe tales, but also provides a new one that surprised me in several ways. Like his other stories, "The Mechanical Theatre of Sebastian von Schwenenfeld" testifies to his love for absurdist literature and his fascination with obscure corners of European history, but unlike the rest, it gives off a sinister glow of mad scientist conspiracy and technical artistry gone wrong. The result is not so much horror as a kind of conceptual unease:

If the automatons somehow sensed his presence, they paid him no mind, allowing Schubert to reach the edge of the open grave unopposed. Within the grave lay a closed casket. The Haarpuder puppet stepped forward, and when it spoke the artificial voice chased a chill down Schubert’s spine. 'You act as though you have never attended a funeral before,' it said.

'Certainly not a puppet funeral,” Schubert replied. He spoke without thought, only pausing after the echo of his words had faded to study the automaton more closely.

The machination laughed mirthlessly. 'They are all puppet funerals, my friend.'

Schubert poked the automaton’s left cheek. It gave way like a silken cushion beneath which lay the cogs and gears that articulated its slightly crooked smile. 'You are clearly a puppet,' he said. 'You are a work of art, to be certain, but you are nevertheless a puppet, an automaton, an artificial construct. How can it be that you speak and act so much like the real Sebastian Haarpuder?'

'You act as though you have never attended a funeral before,' the automaton said, repeating, perhaps, the only words it had been programmed to speak.

'Certainly not a puppet funeral,' Schubert said, echoing his earlier assertion.

It elicited the same dour response from the automaton.

'They are all puppet funerals, my friend.' It turned suddenly, with a smoothness that belied its cog-and-gear nature. 'Why that song?' it asked.

'What song?'

'The automation looked at him, cocked both its head and its mock smile and said, 'You act as though you have never attended a funeral before.'

As I read this quiet story about the quietly unsettling life to be found in dead objects, I wondered how it might wrap itself up. One option was the obvious ending, but Jason E. Rolfe has never been an obvious writer; his equally quiet, equally unsettling solution caught me off guard. It made perfect sense in the context of the story, but also implied a level of strangeness that I had not seen coming. It also reinforced my admiration and respect for its author.

A story like "The Mechanical Theatre of Sebastian von Schwenenfeld" could easily fall out of sight through cracks of genre expectation and readers' assumptions, but it calls for much more: it deserves to be read, appreciated, and praised.

October 31, 2023

"Self-Hating"? That's a Moronic Thing to Say

Since the years of Trudeau the First, I have criticized, openly and loudly, every Canadian federal government and many provincial governments, yet in all of these decades, no one has called me "anti-Canadian" or "a self-hating Canadian."

Why not? For the simple reason that citizens of democratic nations have a responsibility to keep their governments honest and humane. For the simple reason that voters have little power to influence or to modify the behaviour of elected officials, yet must not remain silent. For the simple reason that governments come and go, while people and principles remain.

I can think of another simple reason, perhaps the most compelling: here in Canada, anyone who called someone else "anti-Canadian," or "a self-hating Canadian," would become an instant butt of everyone's laughter. Only a fool would try it.

Why, then, if we are not fools, if we are not idiots, do we stand by in silence while Jews are called "anti-Semitic" or "self-hating" because they reject apartheid, occupation, genocide? Why do we never laugh such nonsense out of the room and out of existence?

October 1, 2023

Murnau's FAUST

Click for a better jpeg.

Click for a better jpeg.Because our corporate-media Petri dish has no memory, no sense of perspective, no desire to learn from the past and no courage to be compared with it, the rest of us need to search actively for greatness. When we find it, the impact can often hit us with unexpected force.

One such knock-out came with Murnau's 1926 adaptation of FAUST. Having now seen the restored print from the "Friedrich-Wilhelm-Murnau-Stiftung," I wish I could have seen it years ago, but good things arrive on their own terms and in their own time.

So much has been said about this film that I have little to add, beyond urging you to see it. As a work of high-budget expressionist Gothic cinematic magic, it compels from start to finish, even if the central portion of the film is more comic than nightmarish (but still well-directed). No need for qualms: the nightmare surges back. The screaming face of Gretchen that hurtles over trees and mountains is merely one of the images that will stay with you long after the film has ended.

Click for a better jpeg.

Click for a better jpeg.For a film almost one century old, FAUST makes many of the current films I've been unhappy enough to see look pale and dull. Enough time has passed to turn its traditional silent-film methods into startling innovations, which allows FAUST to shock in ways that post-modern films cannot. Every technical aspect, from lighting and set design to miniatures and optical effects, stimulates the head and heart while serving the story without fat. As a combination of pure spectacle with pure story, FAUST cannot be anticipated; it can only be seen.

Click for a better jpeg.

Click for a better jpeg.

September 30, 2023

TEOREMA, 1968, written and directed by Pier Paolo Pasolini

Click for a better jpeg.

Click for a better jpeg. PIETRO:

Nobody must realize that the artist is worthless, that he's an abnormal, inferior being, who squirms and twists like a worm to survive. Nobody must ever catch him out as naive. Everything must be presented as perfect, based on unknown, unquestionable rules.Like a madman, that's it. Pane after pane, because I can't correct anything, and nobody must notice. A sign painted on a pane corrects, without soiling it, a sign painted earlier on another pane. But everyone must believe that it isn't the trick of an untalented artist, impotent artist. Not at all. It must look like a sure decision, fearless, lofty and almost arrogant. Nobody must know that a sign succeeds by chance, is fragile, that as soon as a sign appears well made, by a miracle, it must be protected, looked after, as in a shrine. But nobody must realize that the artist is a poor, trembling idiot, second-rate, living by chance and risk, in disgrace like a child, his life reduced to absurd melancholy, degraded by the feeling of something lost forever.

Click for a better jpeg.

Click for a better jpeg.

August 9, 2023

When These Woke Awaken

For me, the most shocking aspect of sudden social crazes would be how quickly they arise and how quickly they die. We, the survivors, look back and say, "How could people have acted like this? How could they have allowed this to happen?"

The past offers many examples of "here today, gone later today" mass delusions. The New England witch craze tore life apart, until, one day, the craze vanished. McCarthyism took a wrecking ball to American society, until one day, it ran out of gas. It simply stopped.

One example from my own lifetime would be the great Satanic Panic media craze. No one mentions it now, but many people were sucked into mass hysteria. Where are these people today? What prompted them to stop shouting, "We must believe the children," and to stop spreading false memories as gospel truth? Do these people look back and wonder, "What the hell was wrong with me?" Do they ever look back at all?

What if they never look back? What would this reveal about human beings and the force of human denial? And what would this imply for tomorrow?

I suspect that, ten years from now, students of history will stare back at our times and wonder how on Earth we could have seen the castration of boys and the genital mutilation of girls as therapeutic; how the hell we could have believed that people are defined not by character or class or learning or achievement or compassion or thought, but by the colour of their skins; how in the name of all that we hold true we could have cancelled people not for their actions, but merely because they disagreed with us on topics where people have always, and always will, disagree?

At the same time, I have to wonder if people in these corporations, governments, and institutions caught up in the current madness will shake themselves, wake up, and wonder, "How could I have believed this?"

Or will, they, instead, move on and never look back... until they fall prey to the next mass delusion?

April 29, 2023

LES DIABOLIQUES and the Curse of Previous Greatness

Click for a better jpeg.

Click for a better jpeg. Henri-Georges Clouzot's LES DIABOLIQUES has never worked for me.

You can understand my confusion. This film has been revered as highly as anything from Hitchcock. Its director has all the indications of cinematic genius. Two of his previous films, LE CORBEAU and LE SALAIRE DE LA PEUR, I would call unsettling, compelling, and extremely effective in the art of torturing nerves. Indeed, many people have been tortured by LES DIABOLIQUES. Why, then, does it bore me?

Without spoiling any details of the plot for the five or six people on this planet who have not seen the film, I would guess that it fails for me in being too long and too tidy.

The trouble, here, is escalation beyond the actual murder. Up until this point, the film sets up its characters, their problem, and their scheme to solve that problem, with a certain efficiency. Beyond this point, complications arise -- too many, I think, and with diminishing returns. We have the pool, and then the suit, and then the hotel room, but then we also have the newspaper article, and then the intrusive old man, and then the punished schoolboy, and then the school photograph, and then the typewriter: these are too much, they take up too much time, and they reduce the tension through sheer weight of delay.

A similar escalation was used in LE SALAIRE DE LA PEUR, but with a difference: the protagonists of that film faced a risk of death at every second, and the more complications that arose, the more likely these people were to die at any moment. This gave the film a tension that made my clenched hands ache, a mood of dread that few films can match. In contrast, escalation makes LES DIABOLIQUES drag onwards into tedium. It should have been turning thumbscrews, but instead, it kept me glancing at the clock: "Are we there yet?"

This bulging pile of escalation comes with a starkness of plot that seems too contrived, too neat, with every i dotted, with every t crossed. In its messiness and panic, LE CORBEAU seems like a nightmare; with its rising tension, LE SALAIRE DE LA PEUR seems like a truck out of control on a mountainside. These films are dangerous; they disturb me; they trouble me long after their endings. When LES DIABOLIQUES finally ends, whatever effect it might have had vanishes in the daylight. (Yes, we have that coda, but instead of disturbing me, it makes me embarrased for the script writers.)

My opinion, of course, is nothing more than one opinion. The film has long been famous, and is often cited as the masterpiece of a great director. In my view, however, the merits of his previous films leave this one pale and weak.

April 4, 2023

Remove One Letter From a Film's Title; Summarize the Story

Buster Keaton. Click for a better jpeg.

Buster Keaton. Click for a better jpeg.LA RÈGLE DU JE.

An illiterate man has one code of conduct, which limits everything he does and thinks.

STAGCOACH.

A catering company must cross the desert to bring a cake to a party, but the stripper inside the cake is not at all happy with travelling conditions.

PSYCH.

A man with a split personality cheats on a university exam by peeking at notes written by his dead mother.

THE LON IN WINTER.

On christmas day, 1183, a man with a thousand faces fights with himself for the English crown.

THE GENERA.

During the American civil war, a humble curator must take back the natural history museum collection of mutated flies that was stolen by enemy agents.

March 19, 2023

Nigel Kneale's THE QUATERMASS EXPERIMENT Revisited

From 1959. Click for a better jpeg.

From 1959. Click for a better jpeg. For the first time since at least 1980, I went back to revisit THE QUATERMASS EXPERIMENT, Nigel Kneale's teleplay published as a book by Penguin, then republished by Arrow.

Beyond, "It's brilliant," I have not much to say, but a few stray thoughts might be worth consideration.

I read this long before I saw the Hammer film, which struck me as less an adaptation than a desecration. The film tossed away the most disturbing and conceptually interesting of Kneale's ideas, and turned his biological threat against all forms of life on Earth into a typically-tentacled space blob. It also rejected Kneale's ultimate solution to the teleplay's problem, but more on that later.

The film in itself might not be at fault in this. To function at his best, Kneale required time and room to develop his ideas. In shorter forms (like the stories of TOMATO CAIN, or the teleplays of BEASTS), or even in film adaptations written by Kneale himself (especially in FIVE MILLION YEARS TO EARTH), Kneale's best qualities vanished, but in THE YEAR OF THE SEX OLYMPICS, THE ROAD, and the longer Quatermass teleplays, his ideas and their implications were given space to grow, with a result of greater scope and greater tension.

Creature model built by Nigel Kneale and Judith Kerr. Click for a better jpeg.

Creature model built by Nigel Kneale and Judith Kerr. Click for a better jpeg. For all that I admire Kneale's development of his ideas, the ending, here, has never quite convinced me. Yes, it is original and unexpected (even if it has been foreshadowed earlier in the play), but is it believable? Even after the passage of decades, I have no firm opinion. It is what it is.

In his introduction to this book, Kneale writes, "It has been pointed out that I don't really write science-fiction at all, but just use the forms of it. I suppose that's true." But is it true?

One thing is clear: Kneale has done his research. His multi-stage rocket and its re-entry process, his correct use of terms like braking ellipse, apogee, centrifugal force, show that he understands the language and basic principles of rocketry. He also understands how to go beyond ideas into their implications, which seems to me a fundamental component of any good science fiction, in print or on film. So yes, Kneale was indeed writing science fiction.

Excellent science fiction. I would call THE QUATERMASS EXPERIMENT the best alien invasion story since Wells, but Kneale would surpass EXPERIMENT six years later, with QUATERMASS AND THE PIT. That one is magnificent.

A Principled Sadist -- Puss In Boots: The Last Wish

WARNING: These comments contain SPOILERS.

Click for a better jpeg.

Click for a better jpeg. Critics and viewers alike have praised PUSS IN BOOTS: THE LAST WISH, and at least for fans online, the most notable character in the film has turned out to be the enigmatic Wolf. I can see good reasons for this.

The Wolf is hardly a complex personality, and much of his impact is the surprise that comes with such a disturbing character showing up in a film ostensibly for kids. His brutality and sadism bring a genuine chill, but for all of the pleasure he takes in cruelty, he operates from clear motives (even if these motives are distorted by a personal resentment), and he follows a harsh but undeniably moral code of honour. This combination -- an affronted sadist with principles -- in itself becomes fascinating.

Another part of his fascination is the role he plays in the narrative. The film sets him up as the enemy who cannot be defeated, and to its credit, solves the problem he poses without any last-minute twists or turns, which makes his final confrontation all the more haunting.

All of this can be recognized with one viewing of the film, but watching it again, I noticed two elements that took me by surprise.

Click for a better jpeg.

Click for a better jpeg. Consider how much the Wolf has in common with Perrito:

Both make a first appearance in disguise, and are mistaken for something else. Perrito seems to be a cat; the Wolf appears to be a bounty hunter.

Both become unwelcome pursuers. Puss In Boots eventually begins to like Perrito, and eventually comes to respect the Wolf.

Both give back to Puss In Boots the sword that he has left behind, even if Perrito only gives back a stick sword.

Both wear clothes associated with death. The Wolf wears a cloak and hood; Perrito wears the sock in which he was meant to be drowned.

Both emphasize the need to treasure life as a gift.

"I find the very idea of nine lives absurd," says the Wolf, "and you didn't value any of them."

Perrito, for his part, says, "I've only ever had one life, but sharing it with you and Kitty has made it pretty special. Maybe one life is enough?"

A final point of comparison: as Perrito had wanted, but very much against the Wolf's intentions, both become therapy dogs. Despite his frustrated rage -- "Why the Devil did I play with my food?" -- the Wolf understands, in the end, that his pursuit has taught a lesson about death and life, and that he cannot justify his personal vendetta. "I came here for an arrogant little legend who thought he was immortal... but I don't see him any more. Live your life, Puss In Boots. Live it well."

These connections between Perrito and the Wolf are so strong that the two could almost be said to reflect each other. Given the obviously thoughtful craftsmanship of the film, nothing would surprise me if the writers had intended such parallels right from the start. They knew what they were doing.

The writers also made clear just how much the Wolf differs from the other main characters. Like him, these characters learn to see their flaws and mistakes. And so, Goldi recognizes that her failure to appreciate the family right in front of her has hurt this family. Kitty realizes that her quest for someone she can trust has been crippled by her own lack of trust. Puss in Boots finally understands that his arrogant lust for glory has led to reckless lives and lost loves. All of these revelations, prompted by outside clues, have to be discovered internally. (Even if Puss in Boots must be jolted awake by the boorish words of his previous jerk selves, he still comes to this recognition by himself.)

But unlike the others, who return to the people they love with a new generosity and a new commitment, both of which are understood and acknowleged by their loved ones, the Wolf never apologizes. When Puss in Boots affirms, with a quiet respect that has grown beyond his previous arrogant dismissals, that he and the Wolf will indeed meet again, the Wolf says nothing; he walks away.

In a film where the characters are so eloquently expressive in their cartoon fashion, the final expression of the Wolf is hard to read. His ferocity, his gleeful sadism, his predatory stare: all are gone, but what remains?

It might almost be regret. It might even be shame.

Click for a better jpeg.

Click for a better jpeg.