DES Richard's Blog, page 2

July 12, 2016

The Dirtiest Pokemon Names

Is this blatant Pokémon clickbait? MAYBE. Is it funny as hell? I sure think so. Am I a curmudgeon who doesn’t see the appeal of Pokémon at all? Most assuredly.

Jigglypuff. Never let your friends find out you like Jigglypuffs.

Koffing. You’ll try it once because it sounds fun, but then it’s just too complicated and not really worth it.

Chansey. We all knew a Chansey, didn’t we? Yeah, we did.

sure it hasn’t

Swinub. Just… don’t ask. It’s better if you don’t know.

Togekiss. Kids these days, always Togekissing.

Probopass. Hurts at first; totally worth it.

Rotom. Hurts at first; not worth it.

Snivy. Probably what Chansey has.

Tepig. You tell people you Tepiged, but you never actually did.

Slurpuff. Don’t do drugs.

Licklilly. I mean… come on.

Squirtle. “I’m so sorry; that has never happened before.”

June 10, 2016

Ten Thousand Forks

Perhaps no word in the English language is so abused as poor irony (‘like’ is up there). It’s the rallying cry of hipsters who drink PBR and wear T-shirts ‘ironically’. And little needs to be said about that song, which contains nothing which is actually ironic, which, if intended, makes it actually ironic. So it is either brilliant or dumb. In any case, irony has suffered much.

And not only has its true meaning been diluted, its actual use has. We take irony- even as defined – to be brief, pithy and generally humorous in some way. But, my dear readers, but, irony is so, so much more than that. It is a great tool in writing, and is not particularly complicated to wield. All you have to do is understand what irony is, and what its intent is. To the first, we turn to the dictionary:

the expression of one’s meaning by using language that normally signifies the opposite, typically for humorous or emphatic effect.

Italics mine in there. Note that is not just for humor. And we thus establish it is using the opposite to get your point across- which is where intent comes in. But that is the 1 definition. Mark this:

a literary technique, originally used in Greek tragedy, by which the full significance of a character’s words or actions are clear to the audience or reader although unknown to the character.

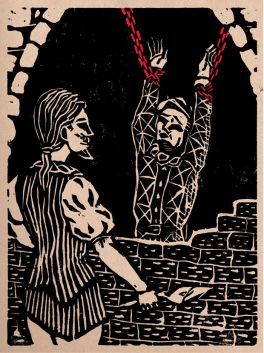

So it is not even novel to use irony in writing- in fact, it is ancient. So how do we use it in our story? There are, of course, myriad examples in literature, but perhaps none better – or, at least, more apparent – than in The Cask of Amontillado, by Edgar Allen Poe. If you haven’t read it, do so now. It’s available for free in a few places, and is a quick read. I’ll wait.

Read it yet? Good. Let’s continue. The best place to start is with the very obvious ironies: Fortunato is easily apparent- he is far from fortunate, at least within the bounds of our story, but in other areas of life is successful. His demise- unsuspected, and likely unwarranted (more on that in a second), is as unfortunate as can be.

He wears a hat with bells – in Victorian times, bells were put on bodies being buried (or even atop their graves) to prevent burial of people who weren’t actually dead and were just in a coma. Fortunato’s hat, however, provides him no such favors, jingling away, the only one to hear being his murdered.

He wears a hat with bells – in Victorian times, bells were put on bodies being buried (or even atop their graves) to prevent burial of people who weren’t actually dead and were just in a coma. Fortunato’s hat, however, provides him no such favors, jingling away, the only one to hear being his murdered.

So there are myriad obvious (Fortunato is implored to turn back; his health is showed concern for; the Mason joke)- yet effective ironies in the story. This is, of course, the easiest use of it – and there is nothing wrong with doing so. It fulfills the definitions above, telling your reader something by using opposites to make the point.

But the story, in its entirety, is one of irony. We begin with

The thousand injuries of Fortunato I had borne as I best could, but

when he ventured upon insult..

Yet we never know what the insult is- or if there even was one. Based on my experience, anyone who is willing to plot a years-long revenge is also the type of person who will take insult at almost anything (but I know very few murderers; I may be mistaken). And even if Fortunato did insult the narrator, does it justify his end? There is no way it could. So while the narrator is often called unreliable in this story, I don’t know that that is the best way of putting it. No, he is the opposite of moral sense- any of us (GG’ers will disagree) deem murder wrong and criminal. But to the narrator, it is his duty and morally right and justified. There is an overarching irony to the fact that the tale is from his point of view, and one that is unblinking in his assertion that he did the right thing.

This does something interesting to us – think of a book or movie that follows the ‘good guys’ through a murder investigation. The one that leaps to my mind is Se7en (UGH that name), which is a fantastic film. But throughout it, we are repulsed by the nature and crimes of John Doe. And even though we recognize that he firmly believes he is right, we never sympathize with him.

The narrator in this story, though- we never sympathize with him either, but we are more and more repulsed by him because it is told to us in a sympathetic tone. It is the irony of the story that drives home our feelings about his actions. Imagine it as a conventional crime story- the body is discovered, there is an investigation, it is revealed at the end that he was tricked and lead to his death. Bad enough, right? But by spending the whole time in the mind of the killer, and him proclaiming not his innocence, but that he is in fact just, there is a different feeling. It’s not a shock, not a jump scare or dramatic reveal, but a growing sense, knowing what is coming and being forced to watch it. It is the irony that draws you in and forces you to be a voyeur to an act you despise – and thus the reader shares in the irony.

–DESR

June 3, 2016

In Praise of Subtlety

Do any of you have that word that you use all the damn time, but can still never spell correctly? And you usually go so far astray that autocorrect looks at it, looks at you, back at the word, and kind of walks away with a defeated shrug, muttering to itself?

‘Subtlety’ is that way for me. And I use that word a lot because it is a word, like irony (more on that later), which is having its meaning eroded. Not in the same way, of course- people use irony to mean all manner of things which are not, in fact, ironic. No, subtlety is simply being lost.

Pretty, POTC, but not very subtle

“Show, don’t tell” is an all-to-frequently repeated adage of writing, usually accompanied by some quasi-poetic, insufferably pretentious statement like “don’t tell me it’s raining; make me feel the raindrops (this post might be insufferably pretentious, I realize). It’s not wrong, but it is over-repeated, to be sure. While there are a whole bunch of authors who go out of their way to make sure you feel raindrops, it gets shoved in our faces a lot that it is f**king raining – rain which does not connect to any greater purpose.

How so? I talked about it earlier – the gut-punch moments of trauma, for example. It propels the plot, sure, it makes the reader feel something, but is it in service of anything greater?

Personally, I deplore writing a word that only means one thing. And so much of literature these days is just that- one thing, a story, it goes from point A to point B, and along the way some shit happened. I loved, I laughed, I cried, I forgot about the story two weeks later.

Perhaps the preeminent example of this is The Raven, by Edgar Allen Poe. In it, Poe doesn’t really try terribly hard to make you care about Lenore, but by the time the door is open – a mere four verses in – we feel apprehension as well:

here I opened wide the door;—

Darkness there and nothing more.

We, of course, know what is coming, but subtly apprehension is built. What’s more, we know what’s coming- in fact, if there is one thing every person knows about Poe, it is that the word nevermore appears in this poem. But let’s talk about that word; or, rather, half of it- more.

By Adam Flynn

The word more closes every verse in the poem, which may not seem terrible subtle, but note that the simple repetition takes the narrator through the gamut of emotion. At first, it cheers our narrator, but drives him madder and madder at the repeated answer. But to us, the repetition is not maddening – it serves another purpose. It keeps a steady beat throughout the story, so that we anticipate that word coming, building to it.

But not the subtle shift in tone – the second verse closes with evermore – he is haunted by her. Then five verses of merely this and nothing more – the interruption, at those points, is inconsequential, and those words convey that nothing changes, for us or the narrator. But then the rest of the verses close with nevermore, with no variation. I think of this poem like the drumbeat that builds tension- slow at first, beating faster and faster and setting out hearts pounding and adrenal glands into a frenzy. Movies use it all the time – Poe writes it. So that beat starts neutral, and beats faster and faster as we anticipate it more, until the crescendo:

And my soul from out that shadow that lies floating on the floor

Shall be lifted—nevermore!

Because this time- it’s not the Raven speaking, it’s the narrator. Every subtle layering throughout has led to this – the ultimate resignation of the narrator, and thus, ourselves.

Each use of more serves something larger- not just to convey the feelings, to make us feel, to tell us it is raining, but to set up, build to, a conclusion.

One of my favorite insults of all time is an old British one, that, presumably, has fallen out of use, but goes “what are you for?” which is to say, “what is your purpose?” Ask that of your words- what are they for, what is their purpose? How does it serve, not just the scene, not just the plot, but the entirety of the story and its ultimate payoff?

–DESR

June 2, 2016

Over the Edge

Edginess is all the rage these days. Has been, for a long time, really. Push the envelope. Do something shocking and different. And that’s is all true and good – to an extent.

Once upon a time, a little film you may have heard of called Gone With the Wind made waves by using the word ‘damn’. Scandalous. And for the time, it was. And I am pretty sure we can all agree that standards when it came to books and movies in the era were pretty far out of whack.

Nowadays, not so much. It is, to borrow from V for Vendetta, the land of do as you please. This has some really good instances- think of Ned Stark or the Red Wedding from Game of Thrones. Shocking, edgy and unexpected.

On the flipside, you have to work really hard to be shocking and edgy, and a lot of authors jump from that side of the line to outright brutality. I’m not going to debate the artistic merits, or lack thereof, of brutality- if that’s your thing, Marquis de Sade is out there for you to read. But think of the sheer number of books and movies that feature an inciting incident that involves a wife/girlfriend and/or child being some combination of raped/tortured/murdered. Shocking, right?

Sorry, no. A couple things: First, no. It’s lazy. Sure, a significant other or child being brutalized would set me on a path to revenge, but it’s still distasteful. Does that mean it should never be done? Of course not- there are plenty of examples of good literature that include those elements. But it is lazy writing. Because of the emotional punch that the reader receives by empathizing with the protagonist, it elicits a reaction.

Sorry, no. A couple things: First, no. It’s lazy. Sure, a significant other or child being brutalized would set me on a path to revenge, but it’s still distasteful. Does that mean it should never be done? Of course not- there are plenty of examples of good literature that include those elements. But it is lazy writing. Because of the emotional punch that the reader receives by empathizing with the protagonist, it elicits a reaction.

But it is overdone, and usually poorly done, and usually the focus is on the wrong thing. Don’t believe me? As any editor how many submissions they receive which feature – and glorify – such brutality. I’ll wait. Back? Told you so. So in addition to being a cheap inciting incident, it’s overdone, and any true edge is lost.

So what would be the non-lazy way of going about it? Think of The Count of Monte Christo- who suffers? Someone innocent? No – our protagonist. We still empathize with him, and with his suffering – in fact, to a depth that we would not achieve were Mercedes raped and/or murdered – which is the road many authors these days would go.

In fact, the tale of revenge is so deep that when he begins to terrorize other’s families, we excuse it! We are so deep in his head, his feelings so much our own, that it traces through the rest of the book. It is not something spurred by a hero kneeling in the rain, holding a body, shouting Noooooooo before going on a rampage. It is a human, who is wronged deeply, and not only goes on a journey of revenge, but by the end, is forced to judge himself for his actions.

Edginess is a useful tool. But it is not the only tool, and if you lean to hard on it, you’ll find yourself with a shallow work, lacking subtlety and substance.

–DESR

May 31, 2016

How to Make a Good Video Game Movie

Video game movies have the same kind of reputation right now that comic book movies did. There is no way to make a good one! Lo and behold, you sure can make a good- even great- comic book movie! This summer, there was a lot of optimism surrounding the Warcraft and Assassin’s Creed movies.

The jury is still out on Assassin’s Creed, but the early reports on Warcraft is… not good. And I am not even a little optimistic about Assassin’s Creed, but more on that in a second.

So what does it take to make a good video game movie?

Please let me write this movie

Make it a good movie. Video games can tell very cool interactive, immersive stories. BioShock, Fallout, and so many others take you and immerse you in your story, via first-person narrative. It’s a great way to tell a story. Movies are also a great way to tell a story, but different. Embrace those differences rather than just trying to follow a story from the video games. That’s what playing the game is for. If you just try to give viewers the same experience as playing the game, it’s doomed from the start. While there are things you can do with a video game that you can’t with a movie, there are things you can do with a movie that you can’t in a game. Do those things.

Do something different. Not just with the way the story is presented, but different than the game itself. Like a lot of early comic book movies, video game movies try to stuff it full of characters and locations from the games. Hey, you loved [character X], right? Here they are on the big screen! Whoop-dee-do. Add some originality! Keep the flavor, but give people an experience that playing the game for two hours won’t.

Don’t take it too seriously. Even if it is a serious story, have fun with it. Do you see how much fun Marvel has in the movies? It’s what makes them great. Think about Hawkeye’s crack in Age of Ultron about having a bow and arrow. It has fun, even in the climax of the film. And it elevates it, since pretty much everyone was underwhelmed with it. So don’t make another dour CGI spectacle. Relax, tell a good story and have fun.

I will do this one for free

Focus on What Works: Going back to the comic book movie thing, what made them work? There were adaptions (see: Snyder, Zach) that are very, super true to the source material, but suck. Why? Total lack of depth and subtext. Sure, they are shot-for-panel recreations of a comic book, but a good movie that does not make. Video games like BioShock and Mass Effect (two of the best games out there) are deep and say a lot more than what is right in front of you. Borderlands is goofy insanity. Capture the essence of what makes a game good, as Marvel has done with the MCU, instead of just cloning the game.

And if you need any help with this, Hollywood, my fees are very modest.

–DESR

May 2, 2016

Smoke, Mirrors and Monsters

Everyone loves a good mystery. The feeling of reading something, that feeling of need to know the answer that forces you to keep turning pages even after you promised yourself just one more chapter eight chapters ago.

The bigger the mystery, the better. The ones that seem unsolvable are the best. They make you wonder how it will resolve satisfactorily. Only, so many times they seem unsolvable because they are. Because, as great as that mystery is, the low that comes from a conclusion that is a total letdown is even worse. It was a dream – they were dead all along – it was in someone’s head and a myriad of others make me drop books (and shows and movies) in utter disgus

Me, upon finding out your character was dreaming or dead or some crap

t, and makes all the good from the first 90% of a story seem bad.

So, dear reader who is also a writer, how do we avoid doing this ourselves? Or, more to the point, to our readers?

In the first place, never bet more than you can afford to lose. What I mean by that is, never raise the stakes beyond what your payoff can be. If your reader is heavily invested every step of the way, and you let them down at the end, your work will not be remembered fondly. BUT, if you give them a solid payoff – even if the mystery itself isn’t as deep – they’ll like it a whole lot more. So if you have this great premise, make sure you have an equally great ending.

Also, don’t go all in at the end (to continue the betting analogy). If you have a super crazy twist that no one will see coming, clue them in a bit. Give your readers some hints that something is coming, or at least some Easter eggs that make sense upon re-reads. Obviously, you don’t want to telegraph what is coming (otherwise it’s not really a twist), but if your story just takes a hard turn out of nowhere, readers will be bewildered, not intrigued.

Finally, know when to fold. Some ideas just don’t work. It’s better to walk away and work on something that does work – and, let’s be real, will sell – than to waste time on something that will ultimately overwhelm. Make a note of the idea, let it stew, and work on other, better projects.

And, for the love of all that is good, please do not let them just be dreaming.

-DESR

April 26, 2016

2016 Hugo Reactions, a Story in Three Gifs

April 15, 2016

Reader Debt

Every so often, I see a plot post/meme/tweet/pagan incantation about what readers owe authors- reviews! Word of mouth! – or something along the lines of this:

“Because I want to keep writing [] and the only way for that happen is for people to buy my books, to get reviews, and *liked* reviews.”

— Tez Miller (@TezMillerOz) April 15, 2016

Which.. no, no that is not. The only way you keep writing is if you keep writing (Note: Tez is quoting from a newsletter there). You may or may not make some/much/any money from it, but that’s the definition, folks.

But let’s be abundantly clear about what a reader owes you: the price of the book. That’s it. If, for example, you wish to read *my* book (which you should- it has been favorably compared to Star Wars, Indiana Jones, Firefly and Twilight Zone!), you may purchase it for two dollars and ninety-nine cents, which you should most certainly do. Once you have done that, our transaction is concluded! I hope you enjoy it!

What readers owe authors

And, in the event that a reader does like it, I hope they do leave a pleasant review and tell all their friends that they should purchase said book as well. But they don’t have to. And so many authors see this as a must. But, friends, it is not. Do they help? You bet! I only have 16 reviews on my silly little collection, mostly favorable, and that helps. Is it the end-all, be-all of book selling? It is not. Does it have any bearing on my continuing to write? Certainly not. If everyone in the universe went and bought it and my next royalty check was for some absurd amount of money, or simply had more number to the left of the decimal place rather than the right, it would probably make writing more easier. But it doesn’t determine if I do.

Likewise, if you do not enjoy my book, I hope you keep your pretty little reader mouth shut and not tell everyone what a steaming heap of prequel-level garbage my book is, and leaving a scathing review that makes me want to never even think about words again. But you can do those things if you want! You don’t owe me jack beyond the two dollars and ninety-nine cents you spent on my book. In fact, if you want everyone who reads your book to write a review, you might regret that. I’m sure people didn’t enjoy mine and refrained from saying so. That is probably a good thing.

So authors, please, enough badgering. Market to people in a way that makes them want to buy your book, and write books that people will want to leave (favorable) reviews of. Stop worrying about how each review and each sale affects your career/sales ranking/ego/whatever.

–DESR

March 30, 2016

In Praise of Leia

There’s a lot of talk these days about strong women in fiction, and rightly so. There is also a ton of talk about Rey being overpowered, and… not so rightly. It’s particularly idiotic when we accept at face value that literally any dude handed a gun in an action movie is automatically Rambo, including, ya know… Rambo. Hell, including Luke himself, which the puppy/GG crowd will fight to the death, but let’s talk about that original trilogy for a second.

Because while you can debate Luke’s Hero’s Journey all day long (Luke sucks), the fact of the matter is Lucas lucked into one of the bad-ass women of all time. I say lucked into, because I have zero confidence in Lucas’ ability to A) write a decent character in the first place and B) because his track record of treating race and gender with respect is… not good. And C) because all the things that makes Leia awesome, I am pretty sure he did by omission. Here is a non-exhaustive list of Awesome Shit Leia Does:

Fights tyranny, not just with guns, but through proper channels and peacefully

Also guns

Resists torture by a Sith Lord

Watches her home planet be destroyed rather than give up information

Still manages to get off a snappy line when she is rescued*

Realizes her rescuers are, uhhhhh, kinda idiots who have no plan, and takes over

Comforts Luke (who sucks) about his friend dying**

Coordinates and attack on the Death Star right after all that

Doesn’t leave anyone at Echo Base until she is literally dragged out

Watches the same Sith Lord torture her crush

Saves Luke’s stupid ass

Tries to save her BF by going undercover in a mob

Gets captured and shoved in a bikini (click that link, kids)

Chokes the guy/slug that shoved her in said bikini

Volunteers for super-dangerous mission

Finds out her dad is the Sith lord who tortured her and her BF

Saves her BF

Finishes super-dangerous mission

Completing super-dangerous mission leads directly to conception of Poe

Sorry I got distracted there

Son turns to the Dark Side

Husband peaces out

She leads a new Rebellion… thingy

POE

Sorry

Husband comes back!

Son doesn’t

Son kills husband

Makes sure Rey, who she just met, goes to Luke (why? HE SUCKS) to train

That’s just so far. Most of us would have curled up in a ball and cried from half of that.

By Chris Trevas

Which brings us to the writing side of it, and the asterisk up there is why I say Lucas lucked out here- that line wasn’t in the script, it was all Carrie coming up with it on the spot. I think Lucas wrote Leia to be a damsel in distress through a lot of it. Because, and maybe this is just me, but if I write about someone getting tortured and watching their planet blow up, I would want to explore the effect it had on them. But Lucas just moves on, as most movies and books do when a woman goes through something traumatic. It’s a plot point, a thing to motivate the actual protagonist (Luke, who sucks) along.

Which brings us to the double asterisk up there- Luke loses a friend who has known for… two days? Ish? Leia watched her home go all ‘splodey. Granted, Luke lost his family and home too, and his pain would certainly be real, but… whole planet. And there she is, comforting him. Lucas & Co. just gloss over her pain, but in doing so, make her stronger. Because she, through all of, handles herself. The only person we see her vulnerable with is Han, and that makes their romance more compelling than the standard guy-gets-girl narrative.

I don’t have a super-huge point here, besides:

Leia is bad ass

Luke sucks

Don’t talk shit about Rey, she is perfect

And, maybe, from the writing side of it, there is a good lesson in not over-thinking things. Let your characters be who they are, and maybe they will be stronger for it.

–DESR

PS Seriously, don’t talk shit about Rey. I will cut you.

March 8, 2016

Writing Prompt: The Little Reader

To be a writer, one must be a reader. For my part, there are few pleasures in life as great as reading a good story to someone.

Even if that someone is a monster (by Kai Acedera). What is being read to him, and why?

as