Lance Fogan's Blog, page 3

September 25, 2023

Blog # 158: POLITICIAN BLANKS ON NATIONAL TV. HAS THIS HAPPENED TO YOU?

Many of my patients with epilepsyon follow-up appointments told me, “No. I haven’t had a seizure in over a yearnow. I’m doing very well.” What they probably are referring to is their pastconvulsion history. No convulsion has recurred. Is this the whole story? Arethey fully aware of their condition.

They may not understand possible brief blank-outs of their awareness or halting of thinking of speaking. did they lose contact mentally with their environment while still not perceiving any focal numbness, weakness/ paralysis, incontinence nor visual problems?

Familyand other observers may see or hear the person stop talking, a speech arrest, just as the nation recently saw on their television screens. A prominent politician suddenly froze up, stopped speaking and did not answer the reporter's question directed at him. As this occurred, he inappropriately stared off to the side, with a vacuous expression, unmoving. after a delay of nearly half a minute while his aides mored in alongside, he began to speak again.

Whatwas that? What happened? Accounts state it was his second such

episode in two months. It suggested to me that TV watchers experienced a

man having a seizure, a non-convulsive type. Since the newsreported he had

a similar episode a month before, more than one seizureis compatible with

epilepsy. If so, was his condition secondary to headtrauma? He had fallen a

few months before striking his head. The mostcommon cause of epilepsy in

the population is in the elderly population. See my pastblogs on this titled,

Mortality in Older Adults with Epilepsy.

Newsreports stated that seizures and strokes were “ruled out.”

But physicians know that small strokes maynot always be visualized on brains scans and neurologists recognize that approximately50% of people with epilepsy, in whom a single EEG is performed, will have anormal EEG. In such cases, multiple EEGs or continuous EEG recording would bemore apt to find an abnormality. Epileptiform abnormalities are not constant inthe brain in people with epilepsy. Conclusion: a normal EEG does not rule outepilepsy. The best manner of making a diagnosis of epilepsy is based on thepatients’ and observers’ histories.

Physicians will also considernon-convulsive epilepsy mimics such as transient ischemic attacks (TIA) or “minitransient strokes,” low blood sugar, migraine phenomena without headache amongother conditions.

I encourage all epilepsy patients tovisit their neurologist/physician with a person close to them if possible.Other people may observe phenomena, clues, of which the patient may be unaware.

Lance Fogan, M.D. is Clinical Professor ofNeurology at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA. His hard-hittingemotional family medicaldrama, “DINGS, is told from a mother’s point of view. “DINGS” is his firstnovel. Aside from acclamation on internet bookstore sites, U.S. Reportof Books, and the Hollywood Book Review, DINGS has been advertised in recentNew York Times Book Reviews, the Los Angeles Times Calendar section andPublishers Weekly. DINGS teaches epilepsy and is now available in eBook,audiobook, soft and hard cover editions.

August 24, 2023

Blog # 157: Cognition and dementia in older patients with epilepsy

Today’shealth care practices have resulted in a substantial rise in the number ofolder adults with epilepsy. In America we have one percent of our population,three million, suffering with epilepsy. In the rest of the developed world, theelderly over 65 also have the highest incidence of epilepsy. It no longer isthe pediatric population that develops the most cases of epilepsy (See my Blog# 15, Epilepsyis most common in the Elderly, at LanceFogan.com)

Olderpeople are more likely to have cognitive decline with epilepsy. There seems tobe a relationship between epilepsy and dementia. Epidemiological findingsreveal that people with late-onset epilepsy and individuals with Alzheimer’sdisease share common risk factors. Medical science isn’t conclusively settledon the cause of Alzheimer’s nor who will develop it but it seems in some peopleto be mediated by underlying vascular changes in the aging brain. Contributingto their development of epilepsy is their survival after brain trauma, strokesand various diseases.1

Theauthors Sen, Capelli, et.al.,suggest that there is considerable intersection between epilepsy, Alzheimer’sdisease and cerebrovascular disease raising the possibility that betterunderstanding of shared mechanisms in these conditions might help to amelioratenot just seizures, but also epileptogenesis and cognitive dysfunction.

1. A. Sen, V. Capelli, M. Husain. Cognition and dementia in older patients with epilepsy Brain, Volume 141, Issue 6, June 2018, Pages1592–1608, https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awy022

hard-hitting emotional family medical drama, “DINGS, is told from a mother’s point of view.“DINGS” is his first novel. Aside from acclamation on internet bookstoresites, U.S. Report of Books, and the Hollywood Book Review, DINGS has beenadvertised in recent New York Times Book Reviews, the Los Angeles TimesCalendar section and Publishers Weekly. DINGS teaches epilepsy and is now available ineBook, audiobook, soft and hard cover editions.

July 25, 2023

Blog # 156: Fatigue and Epilepsy

BJ Mac, Medical and Health Writer, and neurologist, Amit M. Shelat, D.O., reviewed this subject in 2021 and their observations will help explain commonsymptoms with your epilepsy.1

Added to your epilepsy, you feel exhausted, tired, orweak. Fatigue is a much more common symptom in people living with epilepsy thanin the general population. Feelings of exhaustion and weakness can affect dailyquality of life. Understanding this, there are some ways to help manageepilepsy-related fatigue.

The fatigue felt by people living with epilepsy ischaracterized by mental and physical experiences of persistent and extremeweakness, tiredness, and exhaustion.

One patient described being more emotional because offatigue: “Does anyone feel so tired that they feel sad? This often happens tome. I am on a lot of medication, and my seizures are not under control, so Iguess I have many reasons to be tired.”

Another patient reported that fatigue causes daytimesleepiness: One patient described the impact of seizure-related fatigue on herquality of life, writing, “For several years, I wake up after a seizure, and Iam tired for up to seven days and in bed pretty much all day every day. That isthe primary reason I lost my job.”

Several factors can cause a person with epilepsy toexperience fatigue.

Depression

Depression is a knowncomorbidity (co-occurring condition) of epilepsy, with symptoms that vary fromperson to person. A study2 using measurescalled the Fatigue Severity Scale and Fatigue Impact Scale revealed a highprevalence of depression-related fatigue among people living with epilepsy.

This fatigue may sometimes trigger epileptic seizures.A cycle can start to develop: Depression causes fatigue, which contributes toseizures. These seizures then cause more fatigue, which contributes todepression, and so on. Talk to your doctor about how to treat depression tobreak this cycle.

Many patients agree that dealing with depression is acommon aspect of living with epilepsy: “I never thought I would ever have todeal with depression. With epilepsy, depression is a daily battle.”

Nocturnal Seizures

Another important risk factor of developing fatiguewhen living with epilepsy is poor sleep or sleep impairment. Nocturnal seizures(seizures that occur while a person is sleeping) can affect a person’s sleepquality.

A person is considered to have nocturnal seizures ifmore than 90 percent of their seizures occur whensleeping, which is the case in up to 45 percent of people living with epilepsy.

Both generalized andfocal seizure types can occur as nocturnal seizures.Nocturnal seizures tend to occur during the first, lighter stages of sleep or upon waking.

One patient described nighttime seizures as a sourceof fatigue: “I recently had several nocturnal seizures, and I am now veryexhausted. It will take three days for my body to get back to normal. It takesso much out of you.”

Another person described how nocturnal seizuresinterrupt her sleep rhythm and cause fatigue the next day: “Does anyone else everhave a seizure in their sleep and find it hard to fall back asleep? Then duringthe day, it can completely take your energy away.”

Postictal Fatigue

There are several stages to a seizure:

Prodromal phase — When symptoms begin. Aural phase — When altered perception or sensations occur. Ictal phase — The actual seizure. Postictal phase — Recovery time after a seizure. Interictal phase — The time in between seizures.Postictal phases have been found to have higher chronicfatigue scores and fatigue impact scores than ictal phases, with peoplereporting more fatigue and lower energy during the postictal phase. In otherwords, the recovery period after a seizure is a time of intense fatigue.

Many people reported needing to sleep due to intensefatigue during this phase. “I always go to sleep after a seizure,” wrote onepatient. “It’s often compared to running a marathon. Your muscles are weak,everything hurts, and you are plain tired.”

Antiseizure Medications

Antiepileptic drugs commonly cause fatigue. Achange of medication or time to adjust to your treatment plan may be needed toreduce this fatigue.

One patient said about medication-related fatigue:“When I took that medication, I experienced fatigue, anxiety, fear, anger, andmood swings.” Offering some great advice: “When side effects becomeunmanageable, it’s time to talk to your neurologist and ask for a drug that hasfewer side effects.”

Managing Epilepsy-Related Fatigue

Managing fatigue with epilepsy can be challengingbecause its different causes can be interrelated. Tracking symptoms of fatigueand discussing causes and treatments with your health care team is the bestplace to start.

Medicallyreviewed by

AmitM. Shelat, D.O. 2021

2) Fatigue in epilepsy: A systematic review andmeta-analysis Oh-Young Kwona , Hyeong Sik Ahnb , Hyun Jung Kimb, * a Departmentof Neurology and Institute of Health Science, Gyeongsang National UniversitySchool of Medicine, Jinju, Republic of Korea b Institute for Evidence-BasedMedicine, Korea University College of Medicine, Seoul, Republic of Korea

Neurology atthe DavidGeffen School of Medicine at UCLA . His hard-hitting emotional family medical drama, “DINGS, is told from amother’s point of view. “DINGS” is his first novel. Aside fromacclamation on internet bookstore sites, U.S. Report of Books, and theHollywood Book Review, DINGS has been advertised in recent New York Times BookReviews, the Los Angeles Times Calendar section and Publishers Weekly. DINGSteaches epilepsy and is now available in eBook, audiobook, soft and hard covereditions.

June 24, 2023

Blog #155: Robot-assisted brain surgery at Canada’s London Health Sciences Centre provides hope for people living with epilepsy.

Since2011, my monthly epilepsy blog followers (LanceFogan.com) have reviewed severalblogs touching on the efficacy of epilepsy surgery on improving epilepsy—oftencures result. Specialized epilepsy neurosurgical centers evaluate eachcandidate and if the seizure focus can be localized with various testprocedures, and if it is determined that surgery on that focus would be safewithout debilitating side-effects, e.g., speech problems, motor, sensory orvisual complicating deficits, highly successful outcomes are routine.

Reviewmy most recent epilepsy blogs on epilepsy surgery: blog #145 Aug. 25, ’22; blog#121, Aug 25, ’20, and blog #89, Dec 26, ’17.

Bryan Bicknell, the CTV News Reporter, on June 23,2023, reported that a neurosurgeon at the London HealthSciences Centre in London, Ontario, Canada, became the first to perform deepbrain stimulation with a robot!

Neurosurgeon, Dr. Jonathan Lau, reported that allthree of these robot procedures he has done since January 2023, have beensuccessful. All went home a day or two after the procedure. Helikens it to implanting a pacemaker for a bad heart.

“Thisis the same idea. People with epilepsy have a predisposition to havingseizures, so they have irregular rhythms in their brain in terms of electricalactivity. So, the same principle applies. An irregular rhythm there, so we putelectrodes in the appropriate spots with the aid of the robot which is lessintrusive than surgery. The electrodes can restore function and preventseizures.” Lau said it was almost by accident that he and his team atUniversity Hospital decided to employ it for this specific use.

“It was actually afairly routine day when we decided, ‘Okay, because we don’t have the otheroptions let’s use the robot.’ So, we inquired a little bit and it turns outnobody had done this for this indication in Canada,” he explained.

Epilepsy is one of themost common neurological disorders in the world, affecting one percent of thepopulation, more than 300,000 Canadians. And not only is there a stigma aroundthe disease itself, but Lau said there’s also a stigma attached to the verysurgery to improve life for those living with it. Brain surgery can seem scary,but Lau said new technologies actually make it safer.

“With things likerobotic assistance, with improvements in imaging, the risks of the procedureare much, much lower, and it’s just raising that awareness,” he said. Lau addedthat robot-assisted deep brain stimulation surgery is a treatment for somepatients who would not otherwise be considered for surgery.

This is another road youmight consider if your epilepsy is uncontrollable.

Neurology atthe DavidGeffen School of Medicine at UCLA . His hard-hitting emotional family medical drama, “DINGS, is told from amother’s point of view. “DINGS” is his first novel. Aside fromacclamation on internet bookstore sites, U.S. Report of Books, and theHollywood Book Review, DINGS has been advertised in recent New York Times BookReviews, the Los Angeles Times Calendar section and Publishers Weekly. DINGSteaches epilepsy and is now available in eBook, audiobook, soft and hard covereditions.

May 25, 2023

Blog #154: VAGUS NERVE STIMULATION BENEFITS EPILEPSY

An epilepsy diagnosis was made on an 11-year-old girl.Various antiepileptic medications were prescribed but breakthrough tonic-clonicand absence seizures continued. Brain surgery was explored but she was found tohave bilateral epileptic foci. Surgery, therefore, was ruled out.1

A year later Vagus Nerve Stimulation (VNS) wasconsidered a possible treatment. In VNS a battery device is implanted under theskin in the chest and its electrodes are threaded under the skin and then theside of the neck is opened by the surgeon and placed on the left vagus nerveinside the neck. The left and the right vagus nerves course from both sides ofthe brainstem in the lower part of the skull down to the chest and the stomach.The right vagus nerve, however, is not used as it primarily affects the heart.

The Federal Drug Administration (FDA) hasapproved vagus nerve stimulation for people who:

Are 4 years old and older.Have focal epilepsy where the brain activity that causesseizures happens in one area of the brain only.Have seizures that aren't well-controlled with medicines.Vagus nerve stimulation also is considered for people withgeneralized epilepsy.2

Research hasshown that VNS theoretically may help control seizures by: Increasing bloodflow in key brain areas; raising levels of some brain substances (calledneurotransmitters) that are important to control seizures; changing EEG(electroencephalogram) patterns during a seizure.

Stroke recovery: For people who arerecovering from a stroke, vagus nerve stimulation has been FDA-approvedwhen combined with rehabilitation. Vagus nerve stimulation paired withrehabilitation may help people recover function in their hands and arms after astroke.2

Risks:

Having a vagus nerve stimulator implanted is safe for mostpeople. But it does have some risks, both from the surgery to implant the deviceand from the brain stimulation.

Surgery risks

Surgical complications with implanted vagus nervestimulation are rare and are similar to the dangers of having other types ofsurgery. They include:

Pain where the cut ismade to implant the device. Infection. Difficulty swallowing. Vocal cordparalysis. This is usually temporary but can be permanent.

Side effects aftersurgery:

Some of the side effectsand health problems associated with implanted vagus nerve stimulation include: Voicechanges. A hoarse voice. Throat pain. Cough. Headaches. Shortness of breath. Troubleswallowing. Tingling or prickling of the skin. Trouble sleeping. Worsening ofsleep apnea.

For most people, side effects are tolerable and typicallylessen over time. However, some side effects may remain for as long as you useimplanted vagus nerve stimulation.

Adjusting the electrical impulses from the battery deviceunder the skin on the chest can help minimize these effects. If you can'ttolerate the side effects, the device can be shut off.

Then it can be programmed todeliver electrical impulses to the vagus nerve at various durations,frequencies, and currents. Vagus nerve stimulation usually starts at a lowlevel. It gradually is increased depending on your symptoms and side effects.

Stimulation is programmed toturn on and off in cycles — such as 30 seconds on, five minutes off. You mayhave some tingling sensations or slight pain in your neck. You also may have ahoarse voice when the device is on.

Results

If you had the device implanted for epilepsy, it'simportant to understand that vagus nerve stimulation isn't a cure. Most peoplewith epilepsy won't stop having seizures. They'll also likely continue takingepilepsy medicine after the procedure. But many might have fewer seizures — upto 50% fewer. The seizures also may be less intense. It can take months or evena year or longer of stimulation before you notice any significant reduction inseizures. Vagus nerve stimulation also may shorten the recovery time after aseizure. People who have had vagus nerve stimulation to treat epilepsy mayexperience improvements in mood and quality of life.

1) Touchinga Nerve. Brain and Life April/May 2023 p32-35.

2) TheMayo Clinic has reviewed VNS at https://www.mayoclinic.org/tests-procedures/vagus-nerve-stimulation/about/pac-20384565

Neurology atthe DavidGeffen School of Medicine at UCLA . His hard-hitting emotional family medical drama, “DINGS, is told from amother’s point of view. “DINGS” is his first novel. Aside fromacclamation on internet bookstore sites, U.S. Report of Books, and theHollywood Book Review, DINGS has been advertised in recent New York Times BookReviews, the Los Angeles Times Calendar section and Publishers Weekly. DINGSteaches epilepsy and is now available in eBook, audiobook, soft and hard covereditions.

April 21, 2023

Blog #153: Safety Equipment for Epilepsy

Irecently sponsored a booth at the Epilepsy Foundation Los Angelesannual Epilepsy Walk Los Angeles. Each year it is held in the huge parking lot of thefamous Rose Bowl Stadium in Pasadena, California. At this venue I discussepilepsy with the very knowledgeable crowd of several thousand people touchedby epilepsy in some way. I also discuss and sell my novel, DINGS. It’s a strongmother’s story as she defends her bright 8-year-old who the school is about tosend back to the second grade—he’s just not keeping up with his third-gradeschoolwork. The reason is that his complex partial non-convulsive seizure blankouts are not recognized by any of the adults around him. His friends andplaymates think that he seems weird sometimes.

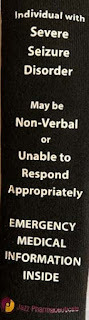

Booths nearby to mine at the Epilepsy Walkwere sponsored by drug companies, epilepsy groups and educationalorganizations. We all were proponents of advancing epilepsy knowledge. Ienclose a picture of one product which I thought to be very helpful with theepilepsy population. It’s a seatbelt cover. It alerts any person who mayattempt to help a person strapped in an automobile who seems in distress orunresponsive. It reads: “Individual with Severe Seizure Disorder. May benon-verbal or Unable to Respond Appropriately. EMERGENCY MEDICAL INFORMATION INSIDE.” This seatbelt cover can be ordered from Jazz Pharmaceuticals.

Booths nearby to mine at the Epilepsy Walkwere sponsored by drug companies, epilepsy groups and educationalorganizations. We all were proponents of advancing epilepsy knowledge. Ienclose a picture of one product which I thought to be very helpful with theepilepsy population. It’s a seatbelt cover. It alerts any person who mayattempt to help a person strapped in an automobile who seems in distress orunresponsive. It reads: “Individual with Severe Seizure Disorder. May benon-verbal or Unable to Respond Appropriately. EMERGENCY MEDICAL INFORMATION INSIDE.” This seatbelt cover can be ordered from Jazz Pharmaceuticals.

It could haveclarified one driver’s condition to responding police who could have actedappropriately rather than by attacking the afflicted person. The Connecticutman had suffered a complex partial seizure while driving and drove his autointo a bank of shrubbery. I described this situation in my Blog #45 titled Police Sued: They Failed to Recognize Epileptic Confusion and Tasered Man, January 22, 2015. He remained behind the steering wheel out of contact with hisenvironment.

Another useful piece of equipment was a video camerawith 4 monitors that could be placed in various places around the house. Thecamera records a child or adult and when a seizure occurs it is more likely tobe seen in a monitor for a quick response. Approximately $400. Learn more at Matt@semialert.com.

LanceFogan, M.D. is Clinical Professor of Neurology atthe DavidGeffen School of Medicine at UCLA . His hard-hitting emotional family medical drama, “DINGS, is told from amother’s point of view. “DINGS” is his first novel. Aside fromacclamation on internet bookstore sites, U.S. Report of Books, and theHollywood Book Review, DINGS has been advertised in recent New York Times BookReviews, the Los Angeles Times Calendar section and Publishers Weekly. DINGSteaches epilepsy and is now available in eBook, audiobook, soft and hard covereditions.

March 25, 2023

Blog #152: Post-Traumatic Head Injury and Epilepsy

On its website, the Epilepsy Foundation recently published an excellent review of Post-Traumatic Head Injury and Epilepsy by Elaine Kiriakopoulos MD, MSc.1

Dr. Kiriakopoulos explains what Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) is: that it results from significant brain trauma, often accompanied by skull fracture, due to collisions and to shaking infants severely. Here, the infant brain is traumatized by thrusts against structures within the skull. Bruising of the brain occurs in significant concussion. Brain bleeding, however, is more serious. Brain scan imaging can usually demonstrate these different injuries. When trauma is severe brain swelling, (edema) often occurs. Such swelling can cause changes in consciousness as coma, confusion, long term headaches, seizures, motor and sensory abnormalities, and chronic cognitive and personality changes.

Mild head injury may just require reassurance and observation at home. If seizures develop within days these may be temporary and don’t necessarily represent epilepsy, i.e., recurrent seizures. If seizures develop weeks, months, or a few years later, this would fit the condition, “post traumatic” epilepsy.

Dr. Kiriakopoulos’ review relates that early post-traumatic seizures in the first week can be seen in10% of such patients and would not necessarily develop into chronic epilepsy nor require anticonvulsant medications. Prophylactically taking anticonvulsive medications after head trauma as a seizure-deterrent is problematical. Seizures developing later than 1 week is likely post traumatic epilepsy and the seizures will recur in 2% of patients. Seizures developing in year 1 are seen in 50% of post traumatic patients. Such post traumatic seizures occurring during year 2 are seen in 30% and after 2 years in 20%. Some patients develop epilepsy 15 years after the head trauma.

Treatment of this condition includes anticonvulsant medications. The more serious the brain injury the more likely the medication will be less effective. In this situation surgical removal of a significant post-traumatic scar shown to be the focus of the epilepsy (scans, EEGs, etc.) and which is also amenable to safe removal of the abnormal brain tissue without causing significant neurological effects can prove curative. I review surgical treatments of epilepsy on my blogs: Blog #114: EPILEPSY SURGERY IN CHILDHOOD AND LONG-TERM EMPLOYMENT IS ENCOURAGING Blog #121: IF YOUR SEIZURES AREN’T CONTROLLED EPILEPSY SURGERY IS SAFE AND REALLY CAN HELP; and Blog #121: IF YOUR SEIZURES AREN’T CONTROLLED EPILEPSY SURGERY IS SAFE AND REALLY CAN HELP.1) Elaine Kiriakopoulos MD, MSc Assistant Professor of Neurology at the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth College. She is Director, HOBSCOTCH Institute for Cognitive Health& Well-Being Dartmouth-Hitchcock Epilepsy Center.

Neurology at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA . His hard-hitting emotional family medical drama, “DINGS, is told from a mother’s point of view. “DINGS” is his first novel. Aside from acclamation on internet bookstore sites, U.S. Report of Books, and the Hollywood Book Review, DINGS has been advertised in recent New York Times Book Reviews, the Los Angeles Times Calendar section and Publishers Weekly. DINGS teaches epilepsy and is now available in eBook, audiobook, soft and hard cover editions.

February 25, 2023

Blog # 151: Pets with Epilepsy and Other Neurological Disorders

My dog, Bagel, over 60 years ago when I was a high school student, would occasionally lay on his belly on out linoleum-floored kitchen, reach his right front leg out, the right corner of his mouth would pull back with foam, his eyes remained open for seconds and then his right front leg would beat the floor as I remember it. After a short moment, this posture ceased, and he appeared listless for some moments and then returned to his usual state. I recognized this as some sort of seizure as a teenager, but my mother and I did not seek veterinary attention. Was this an influence in my becoming a neurologist? I don’t know. On his third violent confrontation with a car, I got a call from a stranger blocks away that my dog was hit by a car. My contact information was tagged on his collar. After nine years he was dead. My aunt loaned me her car. I took him to the Pound in Buffalo. I placed him in their freezer.

This was my first experience with focal motor seizures, epilepsy, secondary to head trauma.

Dr. Carrera-Justiz, a veterinary neurologist, reviewed epilepsy and other neurologic disorders. The veterinarian reviewed neurological afflictions in pets.1 As a veterinary neurologist she accepts referrals from general veterinarians. Evaluations of cats and dogs with seizures could result in a diagnosis of epilepsy, encephalitis, tumors, just as humans. The veterinarian reports epilepsy is more common in dogs than in cats.

Other neurological conditions include stroke. This could manifest with sudden dizziness demonstrated by unsteadiness, paralysis, incontinence. Multiple sclerosis, Dr. Carrera-Justiz describes, can occur based on MRI brain scans and the pet’s spinal fluid, just as is found in humans. Dementia, too, develops in our pets, usually in their mature years over 12. As in humans, the pet may become incontinent, they may no longer recognize their owners and they may stop their usual behaviors.

Cats develop brain meningiomas more than do dogs. These are benign growths. Surgery can remove this benign mass if it is causing seizures or other mass effects.

Veterinarian Dr. Carrera-Justiz suggests querying your veterinarian and how much testing of your pet will cost, what information testing will show, and whether euthanasia may be appropriate.

Lance Fogan, M.D. is Clinical Professor of Neurology at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA . His hard-hitting emotional family medical drama, “DINGS, is told from a mother’s point of view. “DINGS” is his first novel. Aside from acclamation on internet bookstore sites, U.S. Report of Books, and the Hollywood Book Review, DINGS has been advertised in recent New York Times Book Reviews, the Los Angeles Times Calendar section and Publishers Weekly. DINGS teaches epilepsy and is now available in eBook, audiobook, soft and hard cover editions.

January 25, 2023

Blog #150: DINGS Chapter 25

Epilepsy! All my denial—my protective armor—shattered. But of course…something had been undercutting this realization for months. Why had he been wetting his pants at his age? And, the times when I thought he was not paying attention and maybe he seemed confused. Dr. O’Rourke’s interview…Conner’s secrets…all his hidden spells…these dings…over a year. Oh, God. Oh, my God. I leaned forward.

“Epilepsy? So, that’s it. This is epilepsy. Oh, God!” I leaned back and stared up at the ceiling.

Conner had been watching me. He grabbed my hand and gritted his teeth, his eyes wide with alarm. I put my other hand over Conner’s and patted it several times. Sam wrapped one arm around Conner and blinked hard. He reached across our boy’s body to cover Conner’s and my hand with his.

The doctor furrowed his brow as he ran his tongue over his upper lip. “Mr. and Mrs. Golden, we say a person has epilepsy when he has had more than one seizure. Conner’s dings are all seizures. It seems like he’s had many of them, a great many of them.” He looked at Conner.

Conner stared back.

My mouth was so dry. I squinted and gazed above the doctor’s head. My preliminary presumptions surrounding Conner’s convulsion dissolved in tangled confusion. My temples throbbed. I looked at Conner and lowered my head. Conner has to be protected now. I stifled a sob.

I lifted my head and looked into the neurologist’s eyes. My husband gazed straight ahead. I took a deep breath. “I didn’t want it to register, Doctor. I’m sorry. Yes, you and Conner were talking about his dings—or whatever he calls them—those little seizures; apparently there have been lots of them.”

Dr. O’Rourke swiveled his leather chair to the side and crossed his legs. He kept his gaze on me as he tapped his pencil softly on his desk.

Conner watched me, too. He opened his mouth, but kept silent as I turned away.

I looked at the floor and then I closed my eyes and said, “He’s been having these things for over a year? Right in front of me? How could I have missed them? How could I not have seen them?”

I had known that Conner’s convulsion weeks ago could completely change our lives. I just didn’t know how. I didn’t want to know. It was deep in that chamber where I kept secrets, repressed secrets. Conner looked at me again. “Mom! What?”

“Oh, honey.” I wrapped my arm around his thin shoulders. Sam clenched his fists in his lap.

The neurologist spoke in a slow, deliberate voice. “Your son’s seizures are different from the grand mal seizure, the convulsion that brought him to the hospital. Conner’s seizures are caused by abnormal electrical brain activity. They probably originate in just one part of his brain—that would be in his temporal lobe—less likely in his frontal lobe.” He paused for emphasis. “Convulsions affect the whole brain. Anybody witnessing a convulsion would recognize that type of seizure. However, Conner’s dings—as he refers to them—can be harder to recognize…they affect just one part of the brain. What’s so difficult for many people to accept is, as I just said, a cause for epilepsy is often never identified.”

“You mean that, don’t you? You don’t know why they’re happening?” The hostile tone in Sam’s voice surprised me.

“Look. My patients say, ‘Dr. O’Rourke, there are men walking on the moon. Don’t tell me in this day and age that you can’t say why the seizure happened. How can that be?’ Mr. Golden, there are just so many things that we do not understand, especially when it comes to the brain. Medical knowledge humbles us. The more our experience and research teaches us the more we appreciate how little we actually understand. We do not even know how we think or what thinking really is.

“The EEG should document where in the brain these seizures are originating,” he continued. “However, a normal EEG does not mean that there is no seizure disorder. ‘Seizure disorder’ is another term we use that means epilepsy. An EEG can still be normal if the epileptiform discharges do not happen while the test is being done. And that’s common.”

I lowered my eyes and dug my fingernails into the edge of my chair. “What about the Dilantin?” I leaned forward and looked up. “Does Conner still have to take it? I guess so, huh? But I was, uh, we were so hoping, praying, that he could stop taking it today…”

I saw Conner’s puzzled expression. Sam’s eyes locked onto Dr. O’Rourke, but the neurologist focused on Conner.

“Let’s discuss treatment options after I finish—” Dr. O’Rourke coughed into his fist and cleared his throat. “Excuse me. After I finish your son’s physical examination. I want to get a more complete picture of what’s going on before I make any decision about medications.”

He asked him a few more questions to affirm that his mental functions were intact. “Spectacular,” Dr. O’Rourke said with a broad grin. Conner knew the date, where he was right at that very moment and his home address. “Conner is very well-oriented to date and place. He even knows who the president is. Not everyone can tell me that—even adults, believe it or not.”

Our boy beamed.

The neurologist demonstrated that Conner could also add and subtract, count and spell simple words backward—all accomplished appropriately for a third-grader. His memory and his ability to draw, write and name objects the doctor held up were normal, too. “You’re very smart for an eight-year-old.”

“I’m eight and a half, Dr. O’Rourke.”

The neurologist scrunched his eyes shut, grimaced and slunk down in his chair. “That’s right. You already told me. Eight and a half. Sorry.” He straightened up and winked at us.

He asked me about Conner’s past illnesses, immunizations and symptoms in other parts of his body. He also wanted to know about my pregnancies. “Has he ever exhibited any unusual or disturbing behaviors?” His eyes darted between Sam and me.

“No. He’s always been a normal child.” I looked at Sam. He nodded several times.

Conner sniffled and looked up at me.

“Very good. Do any diseases run in the family?”

“No, Doctor,” Sam answered in a solemn voice. “None that we’re aware of, anyway.” We looked at each other. I raised my eyebrows and shook my head in agreement.

Dr. O’Rourke’s face became very serious as he asked, “Do you smoke, young man?”

Our son twisted in his chair and laughed. “No-oooo. The sy…the sychilist at school—the first icky one—she wanted to know if I was married. That was funny.”

“He’s referring to the school psychologist who first attempted to do testing on him in the school, Doctor. Apparently, she and Conner didn’t get along. That’s what both of them told me, anyway. That’s sort of how we got to Dr. Frank Thomas.” My grim expression softened into a smile.

“Oh.” He said to me and then turned back to Conner. “So you don’t smoke. That’s what I like to hear.” The doctor stood up. “Okay, family. Let’s go across the hall to the exam room so I can check Conner over.”

He walked around his desk and put his arm across our boy’s shoulders. “Don’t worry, Conner. I won’t be giving you any shots today. I’ll just be checking your eyes and things.”

We shifted in our chairs and began to rise. Conner said to Sam, “I have to go to the bathroom, Daddy.” His voice had become tremulous again.

“Can’t you wait until the doctor’s finished, Conner?” I asked with a sharp tone.

“No!” He practically shouted and cast a sidelong glare at me. He hitched up his pants and hopped a few times.

“Okay. Let’s go.” Sam took him by the hand.

I sat down again. “I had no idea that Conner’s been having these things, Dr. O’Rourke—and for so long?” I leaned forward. “I’ve gone to the Internet and just about every...but, I never suspected this.” I licked my lips and hesitantly asked in a softer voice, “You really think he has epilepsy, don’t you, Doctor?” My throat and chest were tight. Of courseit’s epilepsy. He just rammed it down our throats. I was so blind.

Dr. O’Rourke went behind his desk. He stood there with a hand on the back of his leather chair, fixed his gaze on me for a moment, and then sat down. He rested his palms on the desk. An inch of light-blue shirtsleeves protruded from beneath the sleeves of his white coat. I noticed “HO” embroidered in dark-blue thread on the left cuff. I did not expect a physician to be so fashion-conscious as to have a monogram on his shirt. I don’t know why I was surprised; look at his bowties. I looked for cuff links, but saw none. The scene was so surreal that for a moment I wondered if I were living it or merely watching myself and the doctor in a silent movie.

“Look, Mrs. Golden, we’ve discovered a lot today. I am probably as surprised about this diagnosis as you are. I did not expect this history of covert, hidden seizures based on my review of the hospital records. I believe that Conner has a form of epilepsy called ‘complex partial epilepsy.’ Its newer term is ‘mesial temporal lobe epilepsy.’ Look at it this way: your son has been suffering; that is why you are here. That is the reality. Now that we have identified what is wrong we can do something about it. We can help him.”

Dr. Choy had said virtually the same thing to me at the hospital. Did they all read the same script?

The neurologist arched his eyebrows. “I expect that Conner will do fine, Mrs. Golden. I understand how upsetting this is for you right now, believe me. But, you’re all going to be fine.”

His words morphed into distant sounds. I forced a weak smile and stared at the framed documents on the wall. Then I asked again, “Are you sure? Are you absolutely sure that Conner has epilepsy? It couldn’t be something else?” I groped for an admission of doubt. “No, no. Of course...It’s just that—” I stared out the window.

“I’m sure, Mrs. Golden. His history is classic: the auras—which are the warnings of the seizures and the smells that he told us that he gets—his confusion, losing control of his bladder. All of those phenomena are textbook symptoms.”

Everything that this neurologist said would be a part of our lives—always, forever. So, this would be my lot in life. I remained motionless. I felt so hollow.

Dr. O’Rourke swiveled his chair around to face the computer on the desk extension. Thuk, thuk, thuk—the keys spoke as he typed. His eyes skimmed the screen, but occasionally I saw him glance at me as I juggled my pain and anguish.

When Conner and Sam returned to the office, Dr. O’Rourke ushered us across the corridor to his exam room. The fluorescent lights flickered on as soon as he opened the door. Conner turned his head from side to side before he entered the room with us.

I remembered that I had read how flickering lights could induce seizures in some epileptics. Was it better to say ‘people with epilepsy’? What should they be called? Was Conner an epileptic? Or was he a child with epilepsy? I squeezed my eyes tight and my body shuddered.

Closed vertical blinds blocked out most of the late-afternoon sunshine that tried to stream through a single window. A rack on the back of the door proffered a selection of brochures on different neurological diseases and various popular magazines and children’s periodicals. There were a few copies of National Geographic, too. A low shelf held several rubber dolls, a Barbie doll, a few toy soldiers and several small action figures similar to the snap-together ones Conner had at home. I wondered if the doctor put them together himself. He must have many children as patients; maybe one of them did it.

Conner was immediately drawn to a colorful diagram on the wall: a gray wrinkled-brain attached to the spinal cord with yellow nerves projecting to all parts of the body.

The neurologist tapped the boy’s shoulder. “Take everything off down to your underpants, Conner. Shoes and socks off, too.” Dr. O’Rourke looked at me as he said that and I nodded. “When you’ve undressed put on the folded gown that’s on the exam table. I’ll be right back.” He smiled and left the room. The door shut behind him with a loud click.

I sat on a green plastic chair and waited for Conner to undress. I recognized several framed photographs on the walls that I remembered having seen on the Internet. The first picture was of a very young Hal O’Rourke in Papua New Guinea. Another large frame had a newspaper article about his interest in Shakespeare and neurology.

Sam moved closer and inspected the pictures, too.

What was the doctor doing now? Where did he go? Paperwork? The bathroom? Dr. O’Rourke had discovered things that all the other doctors had missed. Why didn’t Dr. Choy or Dr. Jackson or even Dr. Thomas—even the school psychologists—why didn’t they figure out what was wrong? What about his teachers? Why did it take so long? And me—his mother! I was the worst of all. I closed my eyes and shook my head at my stupidity. Well, Dr. Choy did mention that it could be epilepsy, but I wouldn’t entertain that diagnosis then. That was preposterous.

Lance Fogan, M.D. is Clinical Professor of Neurology at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA . His hard-hitting emotional family medical drama, “DINGS, is told from a mother’s point of view. “DINGS” is his first novel. Aside from acclamation on internet bookstore sites, U.S. Report of Books, and the Hollywood Book Review, DINGS has been advertised in recent New York Times Book Reviews, the Los Angeles Times Calendar section and Publishers Weekly. DINGS teaches epilepsy and is now available in eBook, audiobook, soft and hard cover editions.

December 26, 2022

Blog # 149: UNEXPECTED COGNITIVE DETERIORATIONS IN EPILEPSY

Several blogs at LanceFogan.com (Blog #145: Epilepsy Patient Passes Driving Test After Brain Surgery; and Blog #121: If Your Seizures Aren't Controlled Epilepsy Surgery Is Safe and Really Can Help) have highlighted the effectiveness of epileptic surgery. The foci of abnormal brain cell neurons in focal epilepsy poorly responsive to anti-epilepsy drugs (AEDs) are removed. If surgically removing these cells is considered safe and the surgery would not affect speech, movement, sensory, memory and visual abilities, this treatment should be strongly considered. Surgical intervention commonly is the best effective, and commonly curative treatment.

Long-term studies have shown that after successful epilepsy surgery in the great majority of patients their brain performance recovers. However, recent studies at the University of Bonn, Germany1 found after the successful surgery that in rare cases neuropsychological performance declines months later. The study found that the surgical tissue removed indicates a rare secondary independent, neurodegenerative disease beyond any direct surgical effects. Evidently, a small subset of patients experiences a significant cognitive decline following surgery for temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE), independent of and in addition to the eventual cognitive sequelae of the surgical treatment. Who are these patients, and what are the underlying causes?

Eight percent of all 355 patients in the study with at least 2 neuropsychological assessments after epilepsy surgery showed a relevant cognitive decline from one postoperative follow-up examination to a subsequent evaluation. The most frequently affected cognitive domain by far was verbal memory (96%), followed by figural memory (33%) and executive functions (25%). Repeated cognitive declines in the time after surgery were observed in 5 of the 24 patients (21%).

The findings indicate that patients who unexpectedly displayed unfavorable cognitive development beyond any direct surgical effects show rare and very particular pathogenetic causes or parallel, presumably independent, neurodegenerative alterations. In those affected, was the removed tissue damaged by secondary disease at the time of surgery - either through inflammation or incipient Alzheimer's dementia-like? The researchers considered with these pre-existing conditions; the body's defenses are particularly active. It's possible that the trauma of the surgical procedure further stimulates the immune system in the brain to attack healthy brain tissue." Further studies are indicated.

Lance Fogan, M.D. is Clinical Professor of Neurology at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA. His hard-hitting emotional family medical drama, “DINGS, is told from a mother’s point of view. “DINGS” is his first novel. Aside from acclamation on internet bookstore sites, U.S. Report of Books, and the Hollywood Book Review, DINGS has been advertised in recent New York Times Book Reviews, the Los Angeles Times Calendar section and Publishers Weekly. DINGS teaches epilepsy and is now available in eBook, audiobook, soft and hard cover editions.