David Conway's Blog, page 9

April 12, 2013

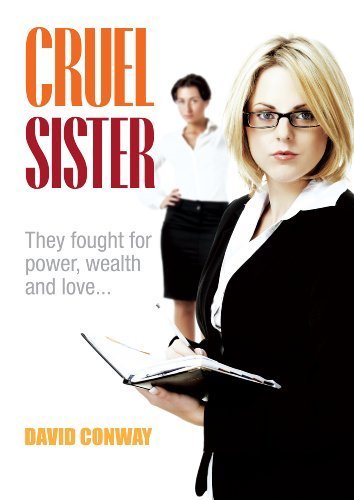

My on air tussle with I’m a Celebrity’s Katie Hopkins

On Wednesday I was Iain Dale’s studio guest on his LBC Drivetime Show. You can listen to the broadcast using the link below.

As well as talking about my novel, Cruel Sister, I was asked to debate “Women in the Boardroom,” with Katie Hopkins, a reality television star who took part in The Apprentice, and I’m a Celebrity Get Me Out of Here! She was the second “Celebrity” to be voted out.

Katie, amazingly, denied there was such any such thing as a “Glass Ceiling,” and claimed that women are kept out of the boardroom only because they take time out to have children! It fell to me to point out that only 4% of the world’s top 500 companies currently have female CEOs.

Even more surprisingly, practically every caller (mostly men) supported her!

Women are kept out of the highest paid jobs because those appointments are almost always made by men, and they like to appoint the people they feel most comfortable with (other men). It won’t change until pressure is put on big companies, but girls have got to speak up too. If Katie is your champion, you’re going to have a long hard journey!

Katie ran unsuccessfully as an independent MEP in the South West England Constituency. She is intending to stand in 2014 for the “We Demand a Referendum” party.

Download: david-conway-debates-with-iain-dale-and-katie-hopkins-edited-version.wav

Katie Hopkins

You can tell a lot about a person by the kind of plane he has…

Jimmy Goldsmith’s private Boeing 757

It’s reassuring to see our MPs applying personal knowledge to the aspects of our lives they most want to change. Zac Goldsmith is staunchly opposed to any expansion of Heathrow. No doubt he remembers his father traversing the Atlantic in a privately owned Boeing 757, flitting between Paris, London and his Mexican palace when he was busy organising the Referendum Party.

Donald Trump, owner of a black Boeing 727 equipped with a movie theatre, oil paintings and a sumptuous bedroom, once quipped: “You can tell a lot about a person by the kind of plane he has.”

I understand that Jimmy’s private airliner was divided into three sections – a dining room, which doubled as a small movie theater, a bedroom for himself, complete with a Jacuzzi bath, and a large salon for up to 20 guests.

I am sure Zac will be able to tell us what its environmental impact was.

I believe he also wants legislation on tax havens.

Hear, hear!

Venice haunts my imagination

Venice haunts my imagination, and several important scenes in Cruel Sister are set there:

This is from Chapter Twenty:

As soon as the plane broke through the clouds Niamh could see the Campanile of San Marco protruding from a sea of terracotta roofs. Venice seemed to shimmer above the pale blue lagoon. It had rained that morning and the air smelled sweet and clean when she stepped outside onto the tarmac. A car pulled up beside them and Miles jumped out. He rushed towards her and they hugged for a long time.

‘Where are you taking us?’ she said to the driver.

He looked confused and said, ‘I was told only to take the luggage.’

‘We’re going by a different route,’ Miles said and led her across the tarmac to the jetty beyond, where a boat was moored. As soon as they were clear of the breakwater the boatman opened the throttle and the engine began to scream as if in pain. There was a gentle swell and the bows periodically rose up and slammed back down onto the water. In the cabin the noise of the huge diesel tore at their eardrums and spray ran across the windows in horizontal teardrops. They were moving fast across the lagoon. Venice grew perceptibly larger ahead of them and they could already see the domes of San Marco. Miles pointed out Torcello on their left and Murano on their right.

The boatman slowed to a walking pace when they reached Castello and softly nudged his launch into a narrow canal. The engine noise fell to a gentle throb as they moved beneath a white marble bridge. Above them, washing hung from balconies and music played from an open window. Then the narrow fondamenta disappeared and they were suddenly in the bright chaos of the Grand Canal, weaving between tangles of black hulls and riding athwart the wakes of vaporetti. The Rialto was thick with gondolas and you could have crossed the canal by stepping from deck to deck. Neither of them spoke; on either side palazzos seemed to be lightly swaying above the purple water.

Albert was waiting for them on the landing stage at San Marco, and he guided them down a narrow alleyway to their hotel. Its walls were dense with ivy pierced only by arched marble windows. The concierge kept up a steady monologue as they signed the guestbook. ‘You have come at a good time,’ he said, ‘it is not so crowded, not so many tourists. But then, life in Venice has always been crowded; we only came to live in the lagoon because we were no longer safe on the mainland. The barbarians chased us here so we built a city they could not reach. Until Mussolini, there was no road to Venice, before the Austrians, not even a railway. Now, the tourists are driving us back the other way.’

Miles said, ‘Let’s go out now, in a gondola!’

The concierge promised to find a special boat and made some phone calls while they waited in the bar. Twenty minutes later they heard a commotion in the canal outside. He had procured an enormous gondola with an enclosed cabin and two gondoliers, one in the prow and another in the stern. He also provided two waiters who carried a hamper of food and wine on board with them.

The gondoliers eased them away from the landing stage with an ostentatious, almost arrogant, skill. Ahead of them a procession of decorated barges and gondolas was moving unhurriedly down the Grand Canal, their decks thick with masked people in mediaeval clothes. Banks of oars dipped in unison; the vaporetti drew respectfully aside and they followed in their wake.

Miles tasted the wine and then said, ‘This is wonderful, where does it come from?’

The waiters looked bewildered and the younger one said, almost regretfully, ‘It comes from here.’

‘You mean there are vineyards in Venice?’

‘No, but there are vineyards in the Veneto, and they are the best in Italy.’

‘That is an exaggeration,’ said the other waiter, who must have been a generation older than his colleague, ‘but Veneto wines are certainly very good. I would say the Soaves and Valpolicellas are among the best.’

‘But this is Fragolino,’ interrupted the first, ‘it is unique to Venice, and there is an easy way to know if they are serving you the real thing. The best Fragolino never has a label.’ He held up the bottle and rotated it to prove that it was, indeed, entirely labelless.

‘It tastes of strawberries and it’s lovely,’ said Niamh, ‘I think we should drink it always.’

‘So do I,’ said Miles, ‘and we shall.’

And then, in an easy way, as if it were a thing he had often done and attached no importance to, he fixed his wide cornflower blue eyes on Niamh’s and said, in a voice so soft that the waiters barely heard him, ‘I love you.’

Niamh smiled and said, ‘I love you too.’

And then he said, ‘Will you marry me?’

Niamh’s eyes widened and a tear may have welled. She leaned a little closer to Miles and finally said, ‘Yes, I will.’

They kissed for what seemed like a long time, and then the waiters applauded and began to sing. Suddenly the ring was in Miles’s hand and then on Niamh’s finger with its bright facets flashing like sparks in a brazier, and all the while the gondola rolled in the gentle swell of the canal, as the enormous diamond split the sunlight into primary colours.

It was a long time before the gondola returned them to their hotel. Niamh went to the suite first while Miles was delayed by a phone call in the lobby. When he joined her he heard tumbling water from the shower. He undressed rapidly in the bedroom, throwing his clothes onto the floor, and then slid back the glass door and stepped into the shower with her. She started, but before she could speak he pressed his lips to hers and held her body hard against his. Her wet skin had an electric feel where it touched his. He slid his hands across her body, stopping to caress the points he knew would make her sigh. He did this patiently and slowly for a long, long time, going back to each point in turn, probing and caressing, moving his fingertips in long gentle circles as the water tumbled over them. She sank her teeth into his shoulder until he almost cried out, then fell to her knees. Miles closed his eyes and pushed his head up into the falling water, knowing that this pleasure was too intense for him to sustain for long.

Much later they fell asleep in each other’s arms. Miles awoke first and made drinks for both of them; he woke Niamh by gently touching the chilled glass against her skin.

‘Did I tell you I love you?’ he said.

‘Not often enough.’

‘Well I do, very much.’

‘I love you too. You’re the only person in the world who can make me forget about my problems.’

‘Good, well, maybe it’s time I reminded you of them. Now you can tell me what your sister’s done.’

‘You remember the private detective I told you about? The one my sister short-changed?’

‘I do.’

‘Well, he’s found out that Branna is trying to buy Metropolitan Studios.’

‘Aren’t they in trouble?’

‘They were, but since they met my sister, maybe not. She’s offered them six billion dollars.’

‘Wow!’

‘Exactly. It’s a lot of money, even for Fayne. My sister doesn’t know anything about the movie business and I have a really bad feeling about it.’

‘Didn’t you tell me that Branna ran some television stations for a while?’

‘She did, but they were small regional TV stations and they didn’t produce much content except for local news and sport. It’s not the same thing as a movie studio.’

‘What does your dad think about it?’

Niamh looked down and did not speak for a moment. The she said, ‘My dad… well, my dad is eighty-two years old. Until recently his age didn’t seem to make much difference to the way he operated, but now it seems like it does. I think my dad knows he made a mistake letting Branna take over from him, but I’m not sure that he’s got enough fight left in him to do anything about it. According to my mom he never mentions the family business anymore, not a word. When I brought it up with him, he just told me to go and talk to Branna.’

‘Have you talked to her?’

‘I wanted to talk to you first. I have almost no relationship with Branna now; she won’t listen to me about anything. In fact, I think part of the reason she’s doing this is to prove I’m not the only one who can take over a company.’

‘How do you think Fayne’s stockholders will react?’

‘I don’t think they’ll like it. Fayne’s stock price is already falling, so I guess rumours have started. It doesn’t sound like Branna’s people are being very discreet. What do you think I should do?’

‘I think you should join me for dinner at L’Osteria di Santa Marina this evening. I’ve booked us a table at eight o’clock. In the meantime, you’d better tell me everything I need to know about Metropolitan and Fayne Corporation. I’m a good listener.’

Miles fetched a laptop and Niamh began. He said little, but from time to time used the computer to check data and find reports. Once again, she noticed the incredible speed at which he read. Only rarely did he make notes, most of the time he relied on his memory. It seemed a long time later when they finally dressed and went back into the street.

San Marco was a sea of masked people in dazzling Renaissance clothes. Hundreds of painted rictal smiles and arched eyes seemed to stare at them as they skirted the square. It was the first day of the Carnivale di Venezia, and the celebrants were already pouring into the tight maze of calli that led uncertainly towards the Rialto. They left the square and walked towards the Campo Santa Maria del Giglio. Above a bridge four men stood in black velvet capes, gold masks and tricorn hats. They stared down at a heavily laden barge which was laboriously passing beneath, with the bargemen pushing down their cargo to clear it. They looked like time travellers transfixed by this glimpse of the future.

The streets became a little quieter with fewer tourists, as if the Carnivale was happening exclusively in San Marco. It was a partly overcast day and there was a quality to the evening light that made the pastel-washed buildings seem almost luminous. They stopped at a multi-coloured bridge. Tiny, even by Venetian standards, it crossed a canal no more than two metres wide. On the opposite bank was a beautiful pink house with almost no embellishment but for wooden shutters and ornamental iron grids on the ground floor windows. Greenery tumbled over its walls, almost reaching the water. A girl with a flower-painted face kneeled to take pictures and the pink ostrich feathers of her headdress fluttered in the light wind. Niamh noticed a leaning tower that defied the perpendicular, like a tree permanently bent by the wind. The angle would have frightened anyone not born in Venice, but it was mysteriously straightened in the reflected water.

At the end of an alley, a basilica suddenly appeared, tightly framed between buildings so close they almost touched. Its white octagonal walls were encrusted with saints, flowers and fruit, and framed against a watercolour sky.

By the time they reached the restaurant Niamh had finished her account. Miles spent a lot of time looking at the menu and being shown various fish and crustaceans that had been caught that day. He chose the Seppia al Nero. ‘This is squid in its own ink,’ he said, ‘it sounds bizarre but tastes heavenly.’

‘OK,’ said Niamh, ‘I’ll try that too.’

When the wine arrived Miles made an elaborate show of tasting it. Then he put down the glass and said, ‘I think you’re right to worry, this sounds like a bad deal to me. The film industry isn’t like other industries. Most companies try to make profits, but those guys try to hide them; auditors have a phrase for it, they call it “Hollywood Accounting”. A movie can cost twenty million dollars to make, earn one hundred and fifty million dollars at the box office, and still lose money.’

‘How is that possible?’

‘The reason is simple; most of the creative people – especially the actors, directors and writers – get a percentage of the profits, so why would the studio want to see a high profit? It’s much better to make a small profit, or better still, no profit at all. The studios are experts at loading their budgets with imaginary expenses. The future of movies may be in small non-studio productions, not in vast behemoths like Metropolitan. Also, the days are gone when most of the income came from people watching movies in cinemas. Today people see content on computers, tablets, even on mobile phones. The technology is changing fast and big companies like Metropolitan aren’t necessarily going to be the first to see the future. The movie world is a labyrinth of opaque accounting and new platforms. Even insiders have difficulty understanding it, so what chance does Branna have? She’s probably going to lose a lot of money, and worse still she’s going to be diverted from her real job, which is running Fayne.’

‘That’s what I thought,’ said Niamh, ‘but what do I do? How do I stop her?’

‘If your father isn’t able to stop her, and you can’t either, then only the board, and ultimately the stockholders can. You need to act quickly, make sure they put pressure on Branna before it’s too late. Little damage will be done to Fayne if she pulls out, but a lot may be done if she goes ahead. The first thing I would do is get this out into the open. You’ve got a friend on the Wall Street Journal and you gave him a scoop on the Bucato takeover; why not give him this story also? The Journal carries a lot of weight with investors. When that’s done, you need to start talking to other board members. If you can convince them, then they have the power to stop Branna. If that isn’t enough then your last port of call is the big institutional stockholders. That’s a tougher assignment though; if they don’t like this deal they’re more likely to sell their shares than put any direct pressure on Branna.’

‘You’re right,’ said Niamh. ‘I suppose I knew those things, but it helps to hear it from someone I trust.’

‘You came a long way to be told that.’

‘Yeah, I guess I did, maybe I wanted to be with you too.’

‘Well I’m glad you came,’ said Miles, refilling their glasses, ‘now let’s talk about us and the rest of our lives; we’ve got a lot of planning to do.’

April 11, 2013

Radio interview on LBC

In the LBC waiting room I read the cautionary notes on the wall: Don’t be nervous, speak into the microphone, put your headphones on, and don’t talk over other guests. The last one I read says: “More than tens of millions of people listening every week!” Perfect to put my nerves at rest.

The LBC Waiting Room

Iain Dale chats while the news runs

April 10, 2013

The Hand & Racquet is gone…

While on my way to LBC I stopped for a quiet, nerve-calming drink at the Hand & Racquet, only to discover that it is closed and derelict. So many of London’s best pubs have closed, heartbreaking.

Tonight I’m on the radio…

Tonight between 7 pm and 8 pm I’m on LBC (97.3 FM) in London with Iain Dale talking about women in power, and my novel Cruel Sister. If you want to listen on the Internet go to: http://www.lbc.co.uk/.

April 9, 2013

Karen Blixen’s house in Rungsted, Denmark.

The homes of authors fascinate me. While staying in Copenhagen we travelled to Rungsted, in the north of Denmark to see Karen Blixen’s house, now a museum dedicated to her work.

David Conway talks about his novel, Cruel Sister.

April 8, 2013

Hogarth House, home to Virginia and Leonard Woolf

While walking down Paradise Road in Richmond, my wife and I passed a splendid eighteenth century house with a blue plaque outside. I discover it is Hogarth House, home to Virginia and Leonard Woolf, and the place where they founded the Hogarth Press. I am fascinated by the houses of authors. Perhaps I imagine a little of their spirit remains, or perhaps I think the building may have influenced the author.

I have always associated the Woolfs with Bloomsbury, and this opulent suburban villa seems curiously unliterary. It looks like, and I imagine is, the creation of a successful local merchant. Maybe she thought so too, it seems Virginia’s mental health deteriorated here, and she finally committed suicide in Sussex.

There is a line from the movie The Hours (as far as I know fictional) which is attributed to her: “If it is a choice between Richmond and death, I choose death.”

This is what she wrote on “Peace Night” in 1919:

“After sitting through the procession and the peace bells unmoved, I began after dinner to feel that if something was going on, perhaps one had better be in it…The doors of the public house at the corner were open and the room crowded; couples waltzing; songs being shouted, waveringly, as if one must be drunk to sing. A troop of little boys with lanterns were parading the Green, beating sticks. Not many shops went to the expense of electric light. A woman of the upper classes was supported dead drunk between two men partially drunk. We followed a moderate stream flowing up the Hill.”

March 30, 2013

I am a late convert to Nancy Mitford…

I am a late convert to Nancy Mitford, and am currently reading Love in a Cold Climate. She was worth waiting for. Is this, or is it not, brilliant?

“Davey’s lapses into insobriety had no vice about them; they were purely therapeutic. The fact is he was following a new regime for perfect health, much in vogue at that time, he assured us, on the Continent.

“The aim is to warm up your glands with a series of jolts. The worst thing in the world for the body is to settle down and lead a quiet little life of regular habits; if you do that it soon resigns itself to old age and death. Shock your glands, force them to react, startle them back into youth, keep them on tiptoe so that they never know what to expect next, and they have to keep young and healthy to deal with all the surprises.”

Accordingly, he ate in turns like Ghandi and like Henry VIII, went for ten-mile walks or lay in bed all day, shivered in a cold bath or sweated in a hot one. Nothing in moderation. “It is also very important to get drunk every now and then.” Davey, however, was too much of a one for regular habits to be irregular otherwise than regularly, so he always got drunk at the full moon. Having once been under the influence of Rudolph Steiner, he was still very conscious of the waxing and waning of the moon and had, I believe, a vague idea that the waxing and waning of the capacity of his stomach coincided with its periods.”