Mathias B. Freese's Blog, page 13

March 3, 2013

An Enthusiasm for Life

One of Freud’s contributions to his new science was that of the association. When this comes to mind, what other ideation or mental construct pops into mind as well… thus sprach the shrink. I think the human mind is a nexus of past and present associations in Faulknerian time, all circling about one another like molecules about atoms past as present and present as past. From associations one can arrive at an interpretation, which is a realistic pattern based upon the evidence given.

For me the greatest cinematic association is Kane’s mental thoughts as he says “Rosebud.” One can only imagine the condensation of his life into that one sled, so overwrought and overwhelmed by feelings for his mother and his separation from her, of having been sold to Thatcher, the banker. Study Rosebud and unrelenting loss is expressed which is an exprience hard to share and harder to metabolize within one self.

I open with this analytic morsel to present my case about an enthusiasm for life. For a night or two an association has taken hold of me, doing its ellipsoid orbits. I am close to an interpretation of that. However, allow me to offer the association itself for your consideration. At this moment I just had an association to Rod Serling. Near the end of his introduction for the Twilight Zone show he was presenting that night, Serling always made some continuing comment about how it was up to the audience’s “consideration.” Associations are forever fascinating to me, for they are intuitive insights. As I age they become more and more omnipresent and more intense.

For your “consideration”: It was about the mid Fifties and I was in high school, that dreadful and gloomy pile of stones and brick of Jamaica High School that made me depressed as a young adolescent. Although Stephen J.Gould roamed its halls with me, that soon to be great evolutionist.There was a late March snowfall, the kind that vanished within days, for the snow was quickly melted by the coming spring’s sun’s rays which also made it good packing for snowball fights. I recall I had an old Kodak Hawkeye box camera, so simple, a lens, a viewfinder and a roll of film, nothing fancy but efficient. For whatever reason, and this is critical for this entire essay, I took the camera with me and went to a local undeveloped field, gnarled trees, stumps, aberrant grass growing wildly and began to take pictures of the flora, here a shot, there a shot. I was just snapping at what I felt [I didn't feel at that time, I was dead to life] was pretty, the snow and the plants, the snow and the field itself, the soon to vanish drifts. When I had the film developed in the murky black and white photos of the time, I showed them to my father. ( I feel now I wanted his approval.) I associate so clearly to what he said, no malice at all, just his usual obtuseness, for he, too, was dead to life. And he said to me, “Where are the people?”

I was taken aback. I hadn’t thought about that. I didn’t realize. In a queer way, I felt guiltily remiss. I was not aware of their absence. I had simply gone out to photograph nature. The poor, dumb bastard of a boy I was then was primitively croaking to dimly exhort himself to feel, I imagine. I was just having pleasure with beauty, and I was shot down by “reality.” “Where are the people?”

I swallowed my father’s reality. Who knew there were other realities? I was with incorporating life rather than projecting upon it. Or, to put it daintily, I ate shit. Hmm, good.

He missed the boat with me. He always missed the boat with me. I was offering up to him my new joy at what I had observed and how it made me feel good, even elated, as I think back on it. I was acting in some fashion, however feebly, upon the world and it would take centuries of psychic time befoere I did that as part and parcel of my daily being. To act upon the world, to be in the world is a wonderful thing to come upon. I was somewhat open to nature, he was not. I didn’t even know that I was trying to be open to life. It was as if I was a frog making just one feeble croak and never more that night.

As I look back upon it, I see myself on very dull levels trying to engage the world — at 16 –to find an enthusiasm for life. It was not something I learned; it was something innate that did not have the willpower to exhibit itself. Again I associate to how a tulip bulb, at times, has to be “forced,” that is, made to bloom earlier than the season says it is time to do so. I have forced many bulbs in my life, a few still not in bloom. My enthusiasm for life was there, but it was nether and very much a surprise to me when it occurred. I was a sublimely repressed young boy.

As I ramble down memory lane with you, I need to clarify the difference between repression and suppression. Although I was a profoundly repressed child and adolescent, closed off to myself, to others, to the world, a dolt, a block, a stone — dialogue from Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar comes to mind: “You blocks, you stones, you worse than senseless things,” the tribune scolds the mob. Let me pause here and say, trust your associations, for they always have meaning for you. In associations you come across yourself, you stumble into you.

A repressed person is shut down unconsciously so, for he is unaware of that which he denies himself; he is closed off and he is profoundly removed from awareness. I have had a carotid artery close off completely and I was totally unaware of that. I could have had a stroke and died. I was lucky. It was discovered and then nothing could be done about it. Using this as an example, repression is like my carotid artery — unknown to me even as harmful and malicious results could be the consequence, and often are. Repression is your not knowing your liver, although it is your organ.

Evil in the world, malignant and malificent evil, is often so repressed that glacial aspects of self are unaware of other regions of the self. When you look at Dick Cheney, (I just mistakenly wrote Chaney as in Lon Chaney here; associate to that reader) as he tilts to his left side (his only liberal tendency) and speaks in his sepulchral voice, we can detect repression that has closed off his human circulation much as his ailing, old heart cut off his oxygen. He has died may times as a young boy and young adult; he probably didn’t take a chance with his camera, for the world was a threatening place to him. I often associate to Cheney as the iconic example of death in life.

Suppression is more of a subliminal conscious experience or a conscious experience; to be earthy, I want to touch her teenage breasts but what will be the consequence in 1956 when sanitary napkins were wrapped in brown paper wrap without the name Kotex or Modess on it, when women were embarrassed to purchase these necessities in supermarkets and drugstores. So, suppression is something that you sometimes consciously work on, like trying to have that erection calm down because the girl on the bus has a voluptuous figure. Suppression stymies. It is a ten-foot psychological and emotional styptic pencil, like the one dad used to staunch a cut while shaving. Yes, suppression was a staunch stypic pencil of the feelings. But, at least, you were aware or dimly awakened to libidinous and pyschological forces worming their way in and out of you. To have unexpressed feelings welling up in you that go unsaid and unexpressed is monumentally frustrating, rigidly Victorian.

I associate again to a wintry night standing on an elevated train, the wind blowing fiercely. I recall that I felt a kind of emotional paralysis in my right arm as I so dearly wanted to drape it across the young female classmate to keep her warm, myself as well, but I was frozen, fear held me back. My past, my culture, my time all condensed into that arm and left it inert. If I could return to that night as I am now, she would have to fend off a male invasion, done with charm and finesse. And so we repair the past with knowledge of who we are today, enjoyable fantasies if we forget the ruefulness that bears the what could have beens.

And as I reflect on this I think of all the losses in life, the small and often tender moments that we did not avail ourselves of. All of life is loss.

I spent most of my youth suppressing feelings and sexual urges. I could not say this to myself then but what I wanted to let out was my need to feel and my need, in turn, to be felt. Early and consistent hugs and embraces would have made a significant impact upon me as I reflect back. I wanted to express, to be expressive. I wanted a great deal as a youth that had nothing to do do with school, career, ambition, all the surface concerns of the Fifties. Combining that which was repressed in me, and the struggle to suppress according to societal needs and cultural mores, I was pretty fucked up by eighteen.

Clearly by eighteeen I was shut down as a young man. By decade’s end, after a divorce, an affair, therapy which was not wholesome for the therapist was incompetent, I merged into the Sixties. Slowly I began to explore what it was to feel, to surrender to the impulses within without judgment, to go with the flow, to experiment with others, to be express, to write, to feel, to smell, to touch, for the Sixties, if not anything else, was a romantic movement much like the one that revealed Keats and Shelley. (All of the Sixties can be felt by listening to the music!) I sloughed off my earlier conditioning. I am much indebted to the Sixties for releasing me from the repressive thoughts and ideation of the Fifties. I risked! I broke out, unfettered myself. I began to become creative and ultimately subversive in how I dealt with society and its conditioning.

An enthusiasm for life has been with me for decades now. At a high school reunion, I imagine, the new Matt would not be recognizable by others, for I have molted many times. I look back and see in reminiscence the thwarted, the very thwarted, feelings and expressivities I could not say or try out; how I was dumb to the world, dumb to myself, a product of rearing no doubt, and I shake my head as I realize how far I have come so that my continuous enthusiasm for life stills abides. However, as I near my end, I still struggle with the choices I make so that I sustain my own life force. I awoke about age 30. And you, reader, in what condition is your enthusiasm for life?

February 25, 2013

Podcast Interview with Bill Williams from Washington, DC

http://www.thebookcast.com/indie-author-mathias-freese-this-mobius-strip-of-ifs/

February 17, 2013

The Paperback Pursuer, Allizabeth Collins, Reviewer

Review Review # 274: The Möbius Strip of Ifs by Mathias B. Freese

Description: (from book-jacket)

In this impressive and varied collection of creative essays, Mathias B. Freese jousts with American culture. A mixture of the author’s reminiscences, insights, observations, and criticism, the book examines the use and misuse of psychotherapy, childhood trauma, complicated family relationships, his frustration as a teacher, and the enduring value of tenaciously writing through it all.

Freese scathingly describes the conditioning society imposes upon artists and awakened souls. Whether writing about the spiritual teacher, Krishnamurti, poet and novelist, Nikos Kazantzakis, or film giants such as Orson Welles and Buster Keaton, the author skewers where he can and applauds those who refuse to compromise and conform…

At the core of these essays is the author’s struggle to authentically express his unique perspective, to unflinchingly reveal a profound visceral truth, along with a passionate desire to be completely alive and aware.

Review:

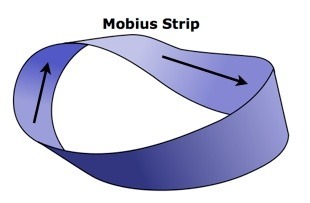

First question: What is a Möbius Strip? I knew that the front cover had a picture of one, but I still wasn’t exactly sure, so I looked up the definition: “A one-sided surface that is constructed from a rectangle by holding one end fixed, rotating the opposite end through 180 degrees, and joining it to the first end…” (merriam-webster.com).

http://mathforum.org/mathimages/index...

Unfortunately, I still wasn’t sure why it was the tile of the book, until I found this definition: “a Möbius strip only has one side and one edge, so ants would be able to walk on the Möbius strip on a single surface indefinitely since there is no edge in the direction of their movement.” (physlink.com). So I finally came to the conclusion that the Möbius strip, (in the book’s case), might represent the disorienting structure/cycle of life; things look one way, but end up another.

I was genuinely surprised when I started reading Mathias Freese’s essays, they were very rich and profound, his outlook on several topics showcasing a range of unyielding emotions – frustration, anger, discontent, depression, doubt, renewal, hope, etc… I was not ready for such a mind-altering read – one that left me in a state of contemplative hibernation. Each essay, especially “Untidy Lives, I Say to Myself”, “Personal Posturings: Yahoos as Bloggers”, “I Had A Daughter Once”, “On the Holocaust”, and “Babbling Books and Motion Pictures”, resonated with me, some for obvious reasons, others because they were so eerily personal. The author’s thoughts were well organized and brutally honest, his no-holds-barred writing style pushing me into debate with myself over my own preconceived ideas and beliefs on certain topics. Even the most simple essays conveyed unfathomable depth, there is no way a reader could put the book down and not linger on the wisdom the author had offered. After reading, I must admit that I feel like everyone has their own Möbius strip – a life full of actions, ideas, stories, regrets, loves, miscommunications, etc, and Mathias Freese has made that point very visual to me. I really enjoyed the book overall, the essay size and formatting were very accessible – I read the essays in order, but it is very easy to pick-and-choose which order a reader prefers. The Möbius Strip of Ifs is not a book to be read quickly or taken lightly – but it will stay with readers for a long time after it has been experienced. Highly recommended to adult readers looking for a refreshing, emotion/thought-fueled read; not for the faint of heart.

February 11, 2013

Tonsils and the Forties

At the end of W.W. II I was five and by the time of the Korean War I was ten. In that decade I was shaped and configured by my environment for the rest of my days. In the Forties I was most unaware of my self, impassive and passive, a receptacle for what I observed on my own and what was put into me by family and circumstances. Life as dumpster. As I look back, as Freud once said, metaphorically I was an archaeological dig, old and and newer artifacts placed randomly here and there crazily deposited by time and event. And so I will “excavate” the removal of my tonsils but first background story.

I “lived,” although that is not the right word; I existed unawakened and unaware, a fetus in the world, newly emerged. I was a tabula rasa. All the years in that decade are smeary, a kind of historical and chronological smog clinging to them, unclear in many instances. I lived at 222 Oceanview Avenue, Brighton Second Street in Brooklyn, years before it became known after the Russian influx as “Little Odessa.” Odessan Jews congregated near the ocean. It was in many ways for me a pastoral environment, the seasons constant, the games constant, and regularity ruled the streets. I loved the neighborhood for it gave me not only sustenance but constancy and constancy is most important while growing up. I knew all the alleyways, urban lanes, shortcuts and streets in a two or three block radius, where to play stoopball, where to play marbles, the location of the library, the candy store for a Charlotte Russe, the hardware store to buy Crayolas and oilcloth to cover my schoolbooks and the grocer to ask for a cheesebox to plant seeds in.

Up the block and close to Brighton Beach Avenue which had an el overhead which cast the avenue into shadows for most of the day, or so it seemed to me, was Dr. Henry Mason’s medical practice. One of my earliest memories was seeing large jars, mason jars, pun intended, in which fetuses soaked in formaldehyde floated like the starchild in Kubrick’s 2001. I was not mortified, I was not traumatized, I just took that in. Nowadays that is outre, unheard of. But back then in the sterile office of Mason, with its chrome and metal tables, its antispetic look which I suppose doctors thought de rigeur, I was unaware of how like the Nazi death camps they bore a close similarity. Obscenely clinical! And so I took all this in. And after all these decades I have metabolized it pretty well and realize it was part and part of our culture — in retrospect, chilling.

Around 6 or 7 I needed to have my tonsils out or that was what doctors did for extra change in those days, for it is not done any longer except for something my son, Jordan, experienced which was “kissing nostrils,” so close to one another he could not breathe. In the Forties it was a very common procedure, if memory serves me right. And here again I will try to capture the unspoken trauma that I experienced.

Several memories coalesce here. I recall having a woman nurse, I suppose, ask me to drop my underwear and she wanted and proceeded to wrap my genitals in a diaper and a diaper pin. I felt shame, yet I went along. As a child I often went along, not because I trusted the outside world but because I did not know what else to do. Resistance was futile. I was the world’s object, to do with as it wished. So this fragment deals with shame, embarrassment, a woman undressing me other than my mother. If it was latently eroticising to me, good for me. Manifestly, it was mortifying. Objects have nothing to say in the matter.

I recall two other youngsters dressed similarly on a bench with me, in assembly line fashion, and, indeed it was an assembly line. One boy who had sat with us was wheeled out on a gurney after the tonsil procedure. I cannot say what I felt as an object but as I look back with empathy for my self it must have been unsettling, to say the least. After a while I was next and brought into a room with a table. I recall a rubber device placed over my face and I was put under with the drug of that time, ether. We were all dealt with as objects by the doctors, by the nurses and by our parents.

As I remember I entered into a dream, in which hundreds of stars circled in a pattern, as if in a wheel. It went on for some time, the moving of the stars in the same round geometic figure. When I awoke I was in a room with other cribs and by my side was a white enameled kidney-shaped pan, I imagine, for spitting up. I was in a slatted jail and no one was there when I woke up, not that I recall. Quite different when my son went in for his tonsillectomy. After that I remember being home for a few days eating large scoops of ice cream which was the prescribed “medication” for the throat.

If we flash-forward to the last few years, I can say that I have undergone several procedures, a colonoscopy and a spinal procedure for spinal sinosis ( a cortisone shot). Earlier colonoscopies over the years usually amounted to having a valium cocktail, if you will, in which I woke up woozy and had to be escorted home. Recently I’ve been administered Propofol, the same drug involved in Michael Jackson’s death. Given the injection by the Sandman, I just went out. After I went out, I woke up. I was not nauseous, I was not woozy, and that is one of the reasons it is being used. During the time I was under, I dreamed nothing. I felt nothing. I was “dead” to this world. And when I woke and after undergoing a few more experiences with this sedative, I began to reflect about death. I just had to, for it was so analogous.

Here I am under sedation,and here I am instantaneoulsy not under sedation, as a line drawn between life and death. And I began to reflect that if death is such a complete absence of self, of hereness, completely absent of sensation, of a dreamworld, I could use this as a mental anodyne for the fear of death. After all, apparently, it is the leaving which is the hardest part of it all. And as I experienced which is not the right word for what I had “felt,” or “sensed” with Propofol, I reentered the world of genomic evolution, dispersed as atoms and molecules to the universes all about us, the massive, titantic cataracts of time and space, of matter. And then I considered once more. Was this state of being, which is not really a state of being, I need words to express this thought and feeling much like what it was before birth. Time out, then time in, and finally, much later on in life, time out again, this strange continuum of existence.

Like a woodpecker on a tear on a telephone pole, these ideas have me perseverating. Perhaps I need console myself; perhaps I am seeking some rationalization to deal with the days ahead, this autumnal season of my life. I’d rather have this belief system of how death, once experienced, is over and then existential emptiness forever without the existent aware or awake of the experience. I become less than a gene. I am atom. I’d rather live with this skinny of how to deal with the end than that of the ludicrousness of heaven and hell. Give me the indifferent, cold and chilling science of death and dying, of atom and molecule, than the febrile constructions of fables spun and story told by priests and rabbis, imans and all the rest.

February 5, 2013

I’m Here, for the Time Being

What an interesting thing, for lack of better words, to self-observe that the time left is shorter than the time I have lived. I associate to the lines in Julius Caesar that mark Cassius as a man who “dost think too much.” I think too much, too much. I remember my mother many decades ago labeling me, in effect, as too heavy for some work and to light for other work, in other words her unwarranted and unnecessary depressive description of me as useless. So I became a teacher, there you go. There is some truth in therapeutic circles that the neurotic builds castles in the sky and that the psychotic lives in them. Or, that the neurotic is a failed artist for he cannot do in life what he really feels he would want to do, thus is frustrated, while the real artist lives all through the day and night and he creates. Lucky is the artist.

The title here betrays my intent, for we are truly time beings. Encapsulated genomic creatures, ruled by genes existentially indifferent to themselves and to us, we are each given a continuum of time to make do with as we like — piss it away, manufacture things and pleasure, be cruel and indifferent, the entire panoply of human differentiation and it all comes to an end. And so I sit here, this mortal sack of shit and bone, contemplating what I have done as a time being

Absolutely not much given the measure of time here on this globe and absolutely nothing with many zeros after it in terms of the indifferent universe. And my mind bobs like those stupid toys on the back seat windows, puzzled by it all, condemned by time to finish the game. I could inflict my own idiosyncratic meaning on it, the one I have lived with for so many years and within those terms choose or decide what is to be done with the time left to me. And since meaning is part and parcel of this species, I could also choose not to give intention to my being, just coast along, like feathers on a wing, insubstantial fluff.

The whole concept as presented here is befuddlement. I back myself into a corner and the only thing I have is choice and that very choice does not resolve anything; it is a temporary prosthesis. As a time being, I can only go along for the ride, like going down a flue in a water park — not much control over that except the avoidance and struggle not to be inundated. Answers for me cannot compete against the relentless self-questioning of how I am to “use” my time — although like our genes, time uses us. Got that! The entire elementary school system should be geared to helping young ones understand and “use” time. Anyone using a cellphone dispatches time in the delusion he or she is manipulating it for self puposes.

Time is the self-globule that blows each of us across our short journeys.

Of late as I near my end I wonder not about a bucket list, a craven cultural artifact that turns life into a wish-list of hedonism and wish-fulfillment. Consider the latent anxiety in not finishing the bucket list. Then, what? I am dwelling these past few weeks if not months in the passage of time as I have lived it, in the remembrance of things past, of what was not done as much as what was done, of the waste of each of our lives, how we foolishly, unwillingly and unintentionally expunge time from ourselves like so much grime from our wrists and hands with soap. And so I stand in the realization that I am 72 and how in the world did I reach this age and who in the world was living in my body as time rushed ahead, carrying me like so many leaves and twigs on its back? Am I detritus? You got it, baby!

Time weighs heavily on me. (I think as soon as one is awake in life time should be weighed heavily each and every day.)I would like to spend the time left to me with intention, creativity and sharing what I have learned about my sojourn on this gorgeous planet savaged by homo sapiens. Equally weighing on me is all that I have learned and no where to unburden my insights, smarts, or know-how. Apparently it is not wanted.

Parenthetically, in Nevada I have discovered that to give one must be aggressive, or to give is not acceptable unless asked for. Nevada is a state of anomie as well as a a state of anomie. What stays in Vegas truly is not registered in Vegas, that’s why it’s safe here. And so I turn inward, searching for that inflection within,that crinkum-crankum of mind that might lead me into new discoveries of my time here. Each day that passes I feel a kind of regret or ruefulness, of something unlived or undone. It is hard work to stay awake in life, often I snore off.

The cast of my mind prevents me from falling into retirement and all the crap that entails — just look at all the claptrap listed in catalogs for senior citizens (argh!). Apparently, in this degraded culture, it is time in which you fill yourself up. I think life is metabolizing experience, and not storage. The elderly often act or feel they are late stage silos. So, true to who I am, I am again a stranger in a strange land. I don’t buy into retirement, I don’t buy into the horrific cultural conditioning we smear onto one another because we are slaves of one kind or another. We pursue happiness, a dreadful task — Jefferson’s unfortunate phrase, for pursuit in itself is wasted expenditure. We are not helped to become aware, awake and to feel which is counterproductive to a capitalistic system. I have always felt out of joint, much akilter.

This kind of personal essay resolves nothing except to be topographical. As a time being pushed and shoved along by aging, disease, years, diet, cause and effect, indifference like a bystander at a death camp, I may existentially choose to just go with it, not to resist, in fact, many of us, including me, have allowed that for years so that, like me, we wake up and wonder what’s it all about, Alfie? I’ve been cursed or blessed by the recognition that tempus fugit for a very long time now and even with that awareness I have not broken through the time bubble.

So, for the time being. . .

January 26, 2013

On Defoe, London and Stevenson

For some latent psychological reason, still dimly unaware to me, I’ve returned to a few books from my college days. Perhaps it is a return to the womb. The magic of the books when first read did not reappear again, not to be recaptured, my folly. I was disappointed. I had thought they were crackerjack when I read them as a young man. And so for equally dim reasons, I thought I’d read books that were valued for youngsters, such as Treasure Island and Robinson Crusoe. By chance, a visit to a book fair revealed an edition from the Sixties with afterwords by critics, to explain what I couldn’t figure out for msyelf.

One book, The Sea Wolf, was inspired by a film of the same name, made in the Forties with Edward G. Robinson, John Garfield and Ida Lupino. It has a stupendously fierce performance of a Darwinian sea captain (Robinson) and the film has dialogue textured with philosophical questions. With all three books in hand I began to nibble away at them. The first read was London’s and what impressed me was his command of the sailing lexicon of the day — jibs, windlasses, spritsails, all the sailorly seamanship of the day that at times I just blew threw it to get at the narrative. London was a sailor and that art has greatly disappeared in the world today, for it is an arcane craft and skill much like cobbling a shoe by hand. I got through the book with its Darwinian view of man as expressed by Wolf Larsen, really London, and it did make me think.

Larsen refers to man and the collective as “yeast,” each spore struggling and in competition with others; one is fatigued by the struggle; however, it is a struggle going on now in each one of our bodies.Today’s evolutionary psychology poses many of the same questions with a different perspective so that I come away believing, thinking that we really are not in charge of anything, just flesh and bone capsules and captives of our genomes working their way through the millenias in random evolution. Evolution, apparently has no estimated time of arrival. (Parenthetically, I was a classmate of Stephen J. Gould at Jamaica High School, Queens, sadly deceased, who went on to become a world famous evolutionary expert.) Who knows what our next fellow will become?

The book that had me annoyed at first was Defoe’s. I imagine the style of the time, it was loaded with semi-colons; it was as if the reader, me, was being punctuated every few words. Growing tiresome, I blew the book off with the hope that I might try it later on in mid-day when I might be more alert and patient. I am rereading it now and I have improved in my attitude toward it. London’s prose was more fluent, Stevenson’s was limber with an occasionaly semi-colon thrown in to annoy me as well. Styles of writing and expression have their fashion.

So I knocked off London first, tried Defoe and put it away and finally entered the world of Stevenson and was able to get through it and then back to Defoe which I am reading now with a better attitude as I said. And as I am awash with the survival of the fittest, buccaneers and English individualists some observations are emerging.

In all three books the sea, islands in the sea, the natural elements, nature, man against nature and man against himself as well as man against society all form a constellations of motifs and themes for the authors to hang their hats on. From what I have read from the 30 or 50 pages in Crusoe, there is a strong flavor of utilitarianism, rugged individualism, thinking out of the box, doing for one self, of being a divergent thinker in a dire situation, like a prisoner plotting his escape and all the devious ways he concocts to make that so.

Dafoe’s Crusoe is more of an adventurous Thoreau, his thinking is purposeful, not that Thoreau’s is not. One becomes aware of a life force trying to sustain itself in every way imaginable. I am vaguely aware of Luis Bunuel’s film of Robinson Crusoe starring Dan O’Herlihy in the early fifties. I may even have seen it but I cannot recall for sure. There is a survival energy in the book that propels it, although I am only half through it.

In The Sea Wolf London brilliantly recreates how a seaman restores a boat with his own hands, his wit and his physical energy that I associate to The Flight of the Phoenix (1967) in which crash survivors develop and rig a new plane from the debris of the old and escape their being being marooned. The cannibalization of the dead into the resurrection of the new is something to behold and such are the pages and scenes in London’s description of how a shipwreck is put together once again by one man’s determined effort to be more than a yeast spore. It is altogether a masterly piece of prose.

Long John Silver is the best written character in Treasure Island. He is ambiguous, somewhat complex, fascinating to behold, brave and most cunning, an Italian Machiavelli in his dealings with individuals and small groups. As a child I saw a few versions of the film, one with Orson Welles and the other with Robert Newton, a famous scene stealer, whose eye-rolling and gravelly voice was compelling. After all, he played Sykes in Oliver Twist, with gusto. All the other characters pale beside this pirate captain, except for Jim Hawkins who to me is Robin to his Batman.

So I have all three books gestating in mind, and for some reason I feel all three, a little less with London’s book, to be a product of industry, that is, the book as an industrious effort, perhaps reflecting the times, the Industrial Revolution itself. I can imagine Defoe brilliantly running a wool factory, a captain of industry to use the old term.

I’ved entered the Eighteenth Century with two of these books and the Nineteenth Century with the other, maritime worlds to a degree and inhabited by industrious, struggling, energetic and purposeful individuals making their way across the earth like ants scuttling across a bread crumb. To a degree, fatiguing. It is as if I am reading outer directed as opposed to inner directed literature, which has its pleasures. We have worry, confusion, fear and all the other human emotions but existential angst does not make its appearance.

Perhaps these three books are statements of a different kind of humanity, like comparing the acting styles of Gable, Cooper, Peck, Stewart with Brando, Hopper, Nicholson, Pacino and DeNiro. To wit, I entered into a different climate of opinion. The age of Freud had not dawned. In other words same old mankind, different sauce.

January 14, 2013

After Reading a Few Pages of London’s The Sea Wolf

3 AM Musings

From a literary friend and editor of an online mag a response to “Archipelago,” one of the stories I am working on now for my next book. Beyond the pale, beyond good or bad taste, it just exists, a written splat thrown up into the sky, hanging there insolently. As I try to hit the literary nail dead on in these stories I know I am not hitting them right on, for all is oblique and indirection. I am “field testing” some of them by submitting to journals online and off. The best time is at this moment as I seize the day in revision. No one story in this impending collection has shouted success; I feel as if I am missing something and perhaps I am. I go ahead in any case, what else is there to do if the subject matter is the Holocaust. The editor friend is not indifferent to the subject nor to my story and for that I am grateful. Otherwise I will face indifference which is the rancid secretion of the species at large. I am not complaining, just offering an observation. When I see blubbery and blustery Beck and vacuous Palin, she who wed the living harpoon, I am only convinced of the tragic experiment which is Homo sapiens. Reading Freud of late has only reaffirmed my take on mankind. Watching Haiti on the tube in the grip of anomie, fecklessness is rampant in our technological response — logistics, etc and bereft of proper priorities. All this catches my eye. Does anyone see the grotesqueness of George Bush (“You’re doing a great job, Brownie”) as a participant in assisting Haiti?

Rummaging through my mind is anxiety about my doctor’s appointment after a blood glucose test I had last week. Nevada is in a sorry state with its medical doctors, almost third world in attitude and skills. Often I feel I am in some Roman century while the empire gradually corrodes, deteriorates and mewls. When the Republican Party does not lend a hand for the larger goals of a health plan for a nation at this time in history, you can taste the bullshit of conquistadors, rugged individualism, Hoover, pre-Roosevelt years and the flinty hardness of the Republican mind which is saturated in the capitalist way of life. We are an inordinately hard and stubborn people who wrap ourselves in the flag, preach the American way and are as intransigent as plantations owners of the antebellum South. One election in Massachusetts could upturn the health plan now in congress; it is a slow-winding disaster and I for one can identify with Haitians, for there is no one truly governing. What do you tell the young? I, for one, would share that all societies are essentially corrupt and leave open to them what course one chooses if this is a fact — which it is.

When I examine and explore the Holocaust as I feel and sense it, at times I barely get a glimpse of the complete anomie that it involved. I will try to share this feeling I have knowing beforehand it will be a lame effort. There are strong elements of this now going on in Haiti, a demoralized people with a demoralizing event on their backs, bereft of leadership, making do each day, corrupted and corruptible, with a bleak history to its past. As I slither into the awareness of what it was to have no one come to rescue you, to save you, to give you food and water, to be herded together and shipped like cargo to unknown destinations, to be despised, hated, decimated with ovens and shooting parties by paramilitary forces, to be asked to wear badges, to realize that the world is indifferent to your plight, that the world does not care, that the world is a hapless mess too busy taking care of its own and that all this horror — and terror, is the by-product of conditioned minds and psychotic national states which only serve to bring home that the species is remarkably wretched, haggard in attitude and quite abusive and vicious in nature. When this feeling coalesces, when this feeling can be realized in some kind of individual awareness, the true existential moment is upon him or her. The sad thing about “humanity” is that we can’t quit — who gets your resignation? And so what is one to do in such desperate mental and psychological straits?

I occasionally wonder about how all our ambitious efforts to acquire wealth, to make a buck, to wage war, to accumulate, to hoard is not some collective monumental displacement of the pre-conscious knowledge that we are a defective species. So that if we shift the burden from awareness of our pock-marked faults we can invest in exterior doings, as if to reduce the slime we really experience about our existence. I avidly believe that we are working in a collective darkness, if not psychoses, as we muddle and pollute, waste time and effort on a world of externals. I imagine that the Holocaust was a time in which every human characteristic was tested and strained, collapsing morally, ethically and in every which way we call human; that words and teachings and religions proved worthless if not useless; that venality ruled; that brutal behavior became king because it afforded power which is really what this species is about — national, psychological, religious, personal and individual.

For me the Holocaust represents not only the lowest level at which humanity could sink, but reflected what we truly are, given that conditions present themselves to allow the actor to remove his mask. I will not be fooled by the Sistine Chapel, by the Mona Lisa, by the Bible, by great architecture and great songs and magnificent prose; beneath it all is the pallor of a death-giving species. And in the Holocaust all this came to the fore, that is why we cannot — thank god– wrestle it to the ground, make it digestible, “sweeten” it. And that is why weaker minds must deny it! The revelation is apocalyptic.

As I have written about Freud’s pessimism, one cannot walk around with that without drawing sustenance from other sources –family, work and love, is a nice triad to become invested in. With writing I define myself but no one definition can hold any one of us within its parameters. It is re-defining that helps me, at least, to keep steady — “Damn the torpedoes, Gridley, full speed ahead!” And there is paradise in the drinking of a good and cold chocolate malted served in a metal server across a marbled counter in a candy store, circa 1948. In the pleasures of life — food, sex, travel, a luxuriant bath we can attain some grip on ourselves, for there is much to despair about. As I learned in my training with clients, try to support the ego if you can. For mental disease is as horrific as a personal holocaust, an internalized self-destructive and abusive horror show — cruelly relentless as a migraine, a protracted neuralgia of the spirit, constricting hope, devastating purpose, crushing intention and devouring self.

I admit the possibility that on some levels my writing about the Holocaust is a sublimated way of writing about the despair I feel as an existent.

January 3, 2013

The Literary Aficionado Review

Thursday, December 27, 2012

This Möbius Strip of Ifs

`Life is best understood backwards.’ Kierkegaard

According to the dictionary definition, `The Möbius strip is a surface with only one side and only one boundary component. The Möbius strip has the mathematical property of being non-orientable. It can be realized as a ruled surface. It has several curious properties. A line drawn starting from the seam down the middle will meet back at the seam but at the “other side”. If continued the line will meet the starting point and will be double the length of the original strip. This single continuous curve demonstrates that the Möbius strip has only one boundary.’

The concept has confounded many thinkers and writers but in the hands of Mathias B. Freese the essence of the meaning of the concept is defined in a series of essays that represent some of the most sensitive and profound thinking of the past few years. Freese writes about psychology, philosophy, thought, family, memories both good and sad, and ramblings about the lives and works of such disparate characters as Buster Keaton, Orson Welles, Nikos Kazantzakis, Peter Lorre to Federico Fellini’s `La Dolce Vita.’

In many ways Freese’s essays are feelings of discontent with the American way of life, his disappointments not only in his career as a teacher, but in many aspects of the way we perceive worth. He often bemoans the manner in which we trash art, spiritual concerns, and creativity in favor of crass commercialism. His previous, highly honored writings about the Holocaust surface here and there and are profoundly moving. In `A Spousal Interview: `After all my years of writing about the Holocaust, the one great learning for me is that it is repeatable; that we learn a little form it, but it will be massaged and kneaded into a sweetener as a historical lesson and not much metabolized by future generations …”Never Again” is an inept, inane and useless slogan, representing more of the ache and agony of the generations after the Holocaust. The Holocaust will be mostly forgotten centuries hence and will be so attenuated that in American textbooks it will take its place alongside the genocide of the American Indian, a paragraph or two or three. If you want a measure of life in this existence, find love, find meaningful work; the rest is illusion.’

These essays are so important for us all to read, so full of richness and quotations that deserve repeating, as the following form `Things Kazantzakis: ` We are spendthrifts with existence, we use it badly. I struggle with “reach what you cannot fine” all the time. No, I will not end up transfigured on a cross, but the struggle, dear reader, the struggle has made my life richer – and dearer.’

Another coupling of essays shares the profundity of his mind. In one titled “About Caryn’ he praises his daughter stricken with Chronic Fatigue and Immune Dysfunction Syndrome (CFIDS) for the courage she demonstrates in coping with her station in life, and that essay is followed by `I had a daughter once’ in which he describes Caryn’s suicide (`she rotted for a week before someone inquired about her.’) and the grieving a father for a daughter has rarely reached such heights of profound tenderness.

This is one of those books that belongs in the library of every thinking and concerned human being. It is a treasure, at times exceedingly painful to read, at times exhilarating. Highly Recommended.

Grady Harp, December 2012

TITLE: This Möbius Strip of Ifs

AUTHOR: MATHIAS B. FREESE

PUBLISHER: WHEATMARK

ISBN: 9781604947236

December 26, 2012

Review in Centrifugal Eye, Eve Hanninen, Editor: Double Wow

Review of This Mobius Strip of Ifs in the Autumn 2012 issue of “The Centrifugal Eye” online literary magazine, pages 81-83 reprinted below:

Reflections on Rummaging

by D. J. Bryant

[image error]Mathias B. Freese first appeared in The Centrifugal Eye’s web pages in the form of an anomalous review of short stories from his collection, Down to a Sunless Sea (2007), by TCE staff writer Ocalive Olaopa Mwenda. (Visit TCE’s archives to read Mwenda’s Absence of Light: Quirks of Dark.*) While Matt Freese is not a poet, his stories and essays are often poetic in tone, and this now-retired teacher and psychotherapist has written often on the subject of writing — a theme always welcome in our journal.

The essays in This Möbius Strip of Ifs were written over four decades, according to Freese, and many were previously published. The first in this collection, “To Ms. Foley, with Gratitude,” even won the Society of Southwestern Authors Award for personal essay/memoir. To whet your appetites, I’ll reveal that “Ms. Foley” was none other than Martha Foley, editor of The Best American Short Stories series (1941-1977).

Recently, This Möbius Strip of Ifs won 2012’s National Indie Excellence Award in the category of non-fiction, and was a finalist for Dan Poynter’s 2012 Global eBooks Awards (Autobiography/Memoirs) .

Award-winning or not, what I enjoyed most about Freese’s essay collection, without question, was his storytelling. Even though the essays within are non-fiction, many are descriptive, concrete narratives. They read, sound, feel like stories. From the classroom to the therapist’s couch to the family-shadowed corners of childhood. Freese accredits this “richness” to having “lain down ‘pilings,’ details on which the story’s scaffolding rests.”

At almost 200 pages of prose, I’m not about to give you a rundown on all the pieces in Möbius Strip, but if I rummage around a bit and pull out some choice scraps from Freese’s memory bag, you’ll get the drift. Right away, I come up with “Teachers Have No Chance to Give Their Best” (pg. 14). While the essay is meant to be a rant, it’s also an honest telling (and yes, a story) about the state of urban high-school ignorance — concerning English, reading, writing, and especially culture, where many students “are sorely confused about their own ethnicity so as to be misinformed of the heritage of others.” Especially sorry case in point: “No one in the advanced tenth grade English class has the

foggiest notion who King Kong is.”

Matt Freese admits a leaning towards Freud (like so many of us), and he’s well-enough read on him to engage us with witty, analytical anecdotes (unlike so many of us who misunderstand or misquote because we haven’t read enough). Freese explores this idea in “Freud’s Cheerful Pessimism”(pg. 27). Other psychologists and psychotherapists will likely agree with Freese when he says “there is much to be said for the analytic approach. All of life is an expression, our expression, to put things into words or to act upon the world. Choose your flavor; I became a writer, others harpoon whales. We all need to make the unconscious conscious, a working definition of psychotherapy that has Freudian salt in it, like a good lox.”

And how about Gulliver’s Travels? Think it’s a kid’s story? Freese will have you grinning like a reaper’s scythe as he links Yahoos to bloggers in another rant he refers to as a “howl.” (Personal Posturings: Yahoos as Bloggers, pg. 42.) It is particularly enlightening to discover how literary reviewers, such as myself, are compared to review bloggers — are we so different? Freese thinks we are, if we’re honest and don’t go about “shoving chicken fat” up authors’ asses.

Speaking of authors, many of you can relate to the careful crafting decisions we must often make, whether these include selecting a point-of-view, or carving unrelated details or sloppy repetitions from an overripe manuscript. Freese’s essay, “In First-Person” (pg. 51), takes a self-critical and accepting look at his own emblematic choices when it comes to writing and editing his stories. A

self-proclaimed tinkerer, he’s learned to wait for his stories’ ends to come to him. Or not.

The essays I liked most in Möbius Strip have something in common; they include nostalgic and multicolored portraits of family members: Matt Freese’s parents, uncle, grandmother. These remembrances also conjure scenes thick with longing, frustration, and oppressed anger. Freese refers to his upbringing as one of “benign neglect,” not from a lack of wants or needs, but “a lack of mothering and fathering.” Still, his parents influence heavily the texture of his writing here.

“Trains = Holocaust and Other Observations, Railfans” (pg. 63) explains Freese’s obsession today with trains and scale models — and how this interconnects with a decision his father made over 50 years ago.

In “Grandma Fanny” (pg. 150), we get to meet his maternal grandmother who was a wayfarer and hoarder, never content to stay for long in any one place, but full of unexpected charms when it suited her. And there are other characters among these essays. Wives, daughters, a son. Freese opens up, maybe sometimes telling more than you want to hear, other times just enough to flood you with empathy.

What was least appealing to me in Möbius Strip was a consistent, mud-dark bitterness that flowed unceasingly from Freese after some of his “howls” hit their crescendos. I can understand degrees of animosity and frustration, especially in light of negative life experiences, but sometimes it overwhelmed my appreciation for the “stories.” I’m not a shallow reader, by any means, and I don’t shy from confessional writing. Yet, I wasn’t a fan of what sounded like potential grudges and unresolved anger that might be skewing Freese’s point of view.

Isn’t this a matter of personal tastes, though? Rightly so. Matt Freese echoes what many of us writers and poets think, feel, and hope to express in our writing as we continue to head, irreversibly, into our twilight years. Sure, yeah, some of us are frustrated, angry, even disgusted with the state of the world. And it’s going to show some of the time.

If you enjoy essays on cultural icons, books, and movies, you’ll like the section called “Metaphorical Noodles,” which noodles about a number of theater and screen actors; and “Babbling Brooks and Motion Pictures” (pg. 112) is essentially a biographical essay of books and stories that impacted Freese’s thinking. He’s got some informative things to say that might lead you to your next good read. Or write.

Freese ends this collection with an essay on something I’m prone to do every time I move house or clean out my files: “rummaging.” You know, it’s where you start sorting papers from folders or boxes that are at least 4-25 years old with the intent to “clean out.” You get through a few pages of a typed document, and then you come across a couple of torn, handwritten notesheets of quotes or quickly-jotted lines of poetry, an old letter you saved for some sentimental reason— and you go sit down and start to read them all instead of tossing them. For you writers, it is often more important to find and re-examine those keepsake scraps than it is to actually “clean out” your office or desk. Freese’s “Reflections on Rummaging” surely bears this out, although my wife would probably be more impressed by a neater office.

December 14, 2012

Something of a Discordant Essay

Several days ago I caught David Lean’s Summertime on TMC. I had seen it in 1955 when a teenager and one scene, I dimly recall, I could not grasp, but now I do. Oh do I. But I am getting ahead of myself. The following morning at breakfast with my wife I began to muse about Hepburn’s memorable performance when other associations came to mind about Lean’s films. I recall The Bridge on the River Kwai which I had seen in a Manhattan movie palace at 17. My friend and I were annoyed that tickets for Around the World in Eighty Days were not available and on a lark took in Lean’s movie which was playing around the corner. Alec Guinness was a new actor to us, and Obi Wan Kenobi to new generations two decades later. So many years later the movie proved a serendipitous and fortuitous surprise. Of the two movies which one would you want to save in your memory bank?

I thought of Brief Encounter with Trevor Howard and Cecilia Howard, a little jewel, of trysting lovers which took place in large part in an English underground with its stations and tea shops. The whistles of the oncoming engines served at times as interruptions (in fact mechanical actors) to the lovers who cherish every heightened moment of their illicit affair, both of them married. It was in black and white. So two Lean movies with trains and then the associations came fast and furious. In Lawrence of Arabia Lawrence leads a vicious assault on an armed Turkish train crossing the desert and massacres all aboard while discovering his own personal lust for blood — he comes out behind a baggage car with his dagger drenched in blood. All three movies cited here served as interrupters or instigators of character action. They are a vital backdrop.

And I thought again. In Dr. Zhivago (1965) I recall trains again, often crossing the frozen wastes of Siberia or carrying Bolshevik troops in a beautiful mounted production with an inert soul; poor Yuri and Lara, loving and losing one another in Russia. Although I did not see Lean’s last production, Passage to India, my wife informed me that trains were involved in that movie. So Lean made at least six films in which trains play a significant role, and Summertime has a final romantic scene in which Hepburn waves goodbye to her lover, Rossano Brazzi, at a train station. And so I must conclude that Lean who was a meticulous craftsman was well aware of the use of trains in his movie career. I wonder what emotional and psychological freight (no pun intended) they carried in his cinematic consciousness.

After all, trains are a most penetrating object, through underground stations, through Asian jungles, snouting across desert wastes, steaming across Indian tracts and frigid tundras. They enter, they pulsate, propel and push, an industrial dynamatic. And in 1959 I did not think about or realize what Hitchcock was up to in the last shot of North by Northwest in which the locomotive enters a tunnel just as Grant pulls up Eva Marie into his berth.

And now I can discordantly return to Hepburn. Hepburn is in Venice, too young to be a spinster, but a virgin, to my mind, on vacation, alone and lonely, and there is a distinction between both words: one is the capacity to dwell within yourself; to be alone is not to be lonely; to be lonely is to be mildly scared, to fear, to be bereft, and to lose compass. Hepburn is lonely. She has a shadowy crater in her self. And in a remarkable scene that I will quickly paint in, a scene that I did not understand then before I grappled with being lonely and being alone, many years later. (We grow old too soon and smart too late, the aphorism opines.)

On a hotel terrace, newly arrived, luggage still unpacked on her bed, Hepburn looks about and sees couples holding hands, others holding arms around one another’s shoulders; she sees a couple she was engaging in conversation walk off, hand in hand. She is observing people who are in relationship, who are connected and you can sense palpably the pain she is feeling and her eyes mist up and she is almost in tears and her eyes fill up and you are watching a marvelous actress painting in her canvas of pain, loss and despair. You are watching a great “silent motion picture” actress strut her self silently. And Hepburn walks about this terrace and the camera tracks her and one almost tastes what I would call a mild anxiety attack well up from within her. An extraordinary moment. Hey Lean, what did you tell Hepburn to elicit that from her? Hey Kate, did you tell him you didn’t need direction?

Since I now know that kind of extraordinarily desperate pain, watching her was like watching a great diva approaching the great moments of her aria and doing it beautifully; one wants to cheer the expertise, the heft, the oomph and rapture of the performance, the commanding presence.

Without too much back story, Hepburn visits St. Mark’s Square (PIazza San Marco) and Lean films this gloriously, the flocking pigeons, the sun licking the surfaces of the Italian stone columns, bathing them in golden hues. The ancient figural clocks above ring out the time. And here Hepburn cut across my heart in another way. While in St. Mark’s filled with tourists, lovers, waiters, bistro tables, strollers taking in the beauty of the plaza, she looks above her and takes in through her eyes the beauty all about her, much as if the sun’s conic shafts of sun rays pass through her eyes, lighting up her interior walls.

Infatuated, she is starved for the chance to absorb all this glory, to be alive, to be in the moment, to realize she is alive. Apparently open to the experience, at some level, she wants or craves to be awakened — to become aware. And the great Kate, several times in the movie, has the camera look down upon her face as her eyes well up with the aspiration to absorb what is before her, to squeeze the orange of life until its pips squeak. It is not an epiphany, it is the moment before. I, too, remember that well, the desire to be saturated for just a bare moment in life.

Several times in the movie we see Hepburn trying to capture her experiences on a movie camera, one that has a key to wind it up with three lenses mounted on the front on a round wheel, close-up, normal and wide angle. She films a storefront, people walking, a canal near her hotel early on in the movie, in a feverish attempt to “capture” experience. And I am reminded of Japanese tourists in Paris who had their cameras screwed into their faces as if they might not capture everything they came about, rather pathetic. In other words, Kate allows the camera to come between herself and what she sees; she is into capturing experience instead of registering, a common malady with human beings up to this moment. Half way through the film, the camera disappears and Kate enters into registering and experiencing the events and people in her life. Venice gifts her with an Italian lover, the rest is plot.

As Kate waves farewell to her Italian lover on the train that is taking her back to her world, one feels a tinge of sadness, not only for her decision not to stay and completely surrender to her self, free of American provinical values and conditioning, but to continue working on her newly found capacity to enter the world, to be vibrantly alive and open. At least when she returns, one feels, that experience will not be recorded and registered through artifice, a camera, to wit, but captured within the lens of the self.