Precious Williams's Blog, page 2

April 14, 2011

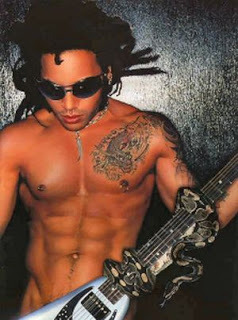

Lenny Kravitz: 'Don't Call Me A Sex Symbol'

one of my very first celeb interviews :) for the Evening Standard (London)

'Don't call me a sex symbol'

Precious Williams

Updated 00:00am on 27 Nov 2000

Lenny Kravitz is late. His "people" (a personal chef, band manager, tour manager, personal manager, publicists, fixers, press officers and assorted attractive but apparently purposeless hangers-on) are clustered in the bar of a small French hotel, making frantic mobile phone calls and periodically mouthing the words "any minute now" to me. Lenny has already been on his way "any minute now" for more than five hours.

When Lenny finally saunters into the hotel lobby, he doesn't apologise for his lateness. Flanked by a thickset bodyguard and his 11-year-old daughter, Zoe, he throws out nonchalant greetings of "Yo" and "Alriiiight" before ducking into the lift. Minutes later, I'm ushered up to his hotel room.

"Hey," he drawls lazily, arching an eyebrow. He is slumped on the sofa, his lithe body swamped by a shapeless and shabby burgundy cardigan that is held together with a giant safety pin. A matching knitted cap is pulled down low over his forehead. Lenny Kravitz is possibly the only man in the world who can make saggy knitwear look sexy. I ask whether he's growing his trademark long dreadlocks back - surely the only excuse for sporting such unflattering headgear.

"No. They contained too much bad energy, y'know?" he says in his laid-back LA drawl. "They went through a lotta heavy things. I had to let 'em go."

The dreads may have gone for good but the piercings are still very much in evidence. Six diamond studs and hoops in his left ear, one on either side of his nostrils. Lenny has, he tells me triumphantly, another three piercings that are out of my sight. One silver ring in each nipple and a third, that he refers to as "the family jewel", hidden beneath his flared jeans. "I enjoy having them done," he says with a satisfied smirk. He claims that being a sex symbol is the "furthest thing" from his mind. He finds it absurd that a musician who doesn't even comb his hair should be an international pin-up.

Whether Lenny approves of his lady-killer image or not, he certainly knows how to take advantage of it. In the course of his career he has (allegedly) seduced Madonna, Kylie Minogue, Natalie Imbruglia and French former pop star Vanessa Paradis. Currently he's strutting around town with Hollywood starlet Gina Gershon (who stars in the video to his forthcoming single, Again), although he has also been linked with model Devon Aoki.

Lenny's most enduring relationship was with Cosby Show actress (and Zoe's mother) Lisa Bonet. But their marriage broke down shortly after Lenny penned the raunchy Justify My Love for Madonna. Lenny wrote a song for Lisa, It Ain't Over Til It's Over, but sightings of Lenny smooching with Madonna seemed to convince Lisa that their marriage was indeed over. Following the release of Justify My Love, Lenny is said to have dubbed Madonna a "cold bitch", but today he speaks of her fondly. "She's my girl. We're very good friends."

He is also so spiritually close to Lisa these days that he has given her his shorn dreadlocks to keep in her LA home. "But I'm single now," he adds, momentarily avoiding eye contact. "It's just me. The only woman in my life is my daughter, Zoe. She lives with me. It's a lot but you make it work."

Like Zoe, Lenny was an only child. Raised mainly by his grandparents in Bed-Stuy, a ghetto-ish enclave of Brooklyn, Lenny lived on the same block as Puff Daddy. Lil' Kim and Spike Lee lived just around the corner. Then, during his teens, he was transplanted to star-studded LA, to live with his parents. He got his first taste of the glamour and excess that now dictate his lifestyle when he attended Beverly Hills High School. "Teenage kids driving Porsches and Ferraris. But I didn't even have a car. I rode the bus. And I never even had, like, a quarter, y'know?"

It is unlikely that Zoe will ever have to catch a bus to school. Today, multi-millionaire Lenny flits between a popart mansion in Miami and a beach home in the Bahamas. His mother, TV sitcom actress Roxy Roker, was a native of the island. His father, Sy Kravitz, is a Russian/Jewish TV producer. "My mom always taught me that I was as much one thing as the other," says Lenny of his multi-ethnic heritage. "She taught me to be proud of both sides, of being Jewish and West Indian. But at the same time my mom taught me that society would view me only as black."

Did this cause him confusion as a child? His expression alters from arrogance to momentary anger. "I've never had a thing about what I am. I never had a problem."

Maybe, but plenty of critics have had a problem with his identity. Throughout his five album, 15-year career, he has constantly been accused of not being black enough. And despite selling 12 million albums and receiving three Grammy Awards, black radio stations throughout America still refuse to play his music. "Everyone forgets that black people actually invented rock 'n' roll. I may not do what black people are supposed to be doing, but that's just so closed.

"People call me naive for writing all these love songs," he continues. "But I don't believe that."

February 28, 2011

Can you be black and *English (*English as opposed to British)?

February 1, 2011

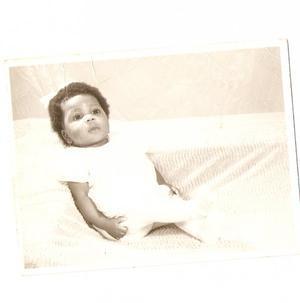

Nursery World

A couple of days after I was born, my mother advertised me in a magazine called Nursery World. I've seen the original ad but no longer have access to it. It said something like 'Nigerian baby girl needs new home.' Back then - in the 1970s - literally thousands of west African babies and children were advertised in this way. Not only in Nursery World but also in the Evening Standard and in local newspapers in the Home Counties too. Naturally, these advertisements were like gold dust to paedophiles and other shady types- they could flick through the pages of ads and select children to abuse who met their requirements.

A couple of days after I was born, my mother advertised me in a magazine called Nursery World. I've seen the original ad but no longer have access to it. It said something like 'Nigerian baby girl needs new home.' Back then - in the 1970s - literally thousands of west African babies and children were advertised in this way. Not only in Nursery World but also in the Evening Standard and in local newspapers in the Home Counties too. Naturally, these advertisements were like gold dust to paedophiles and other shady types- they could flick through the pages of ads and select children to abuse who met their requirements.

I know very little about the first person who responded to my mother's ad. All I know is that this person sent away for me after seeing the Nursery World ad and my mother duly delivered me to them - somewhere in Somerset. I was about nine days old when I arrived. For reasons as yet unclear, my mother supposedly didn't visit me again for four to six weeks. When she did finally visit me, she was, she's said, appalled by the state I was in. I don't know what is meant by that - it's not clear whether I'd been neglected, abused or was simply unhappy because I was pining for my mum. Anyhow, my mother removed me immediately and took me back to live with her. I would have been about 7 weeks old at this point. But by the time I was 9 weeks old, I was advertised in Nursery World again! This time a white woman in her late 50s, based in West Sussex, replied to the ad and I was sent to live with her when I was 10 weeks old. I called her Nanny. She'd previously fostered two other west African babies who she'd seen advertised in Nursery World - but their birth parents had finally taken them back.

I know very little about the first person who responded to my mother's ad. All I know is that this person sent away for me after seeing the Nursery World ad and my mother duly delivered me to them - somewhere in Somerset. I was about nine days old when I arrived. For reasons as yet unclear, my mother supposedly didn't visit me again for four to six weeks. When she did finally visit me, she was, she's said, appalled by the state I was in. I don't know what is meant by that - it's not clear whether I'd been neglected, abused or was simply unhappy because I was pining for my mum. Anyhow, my mother removed me immediately and took me back to live with her. I would have been about 7 weeks old at this point. But by the time I was 9 weeks old, I was advertised in Nursery World again! This time a white woman in her late 50s, based in West Sussex, replied to the ad and I was sent to live with her when I was 10 weeks old. I called her Nanny. She'd previously fostered two other west African babies who she'd seen advertised in Nursery World - but their birth parents had finally taken them back.

After more than a year with Nanny, who dressed me up like a little princess and seemed delighted to look after me, my real mother took me back, seemingly for good. Nanny was devastated and found a new African baby girl in Nursery World's classified pages and sent away for her. Several weeks later, with her new foster-daughter installed in her home, Nanny was flicking through Nursery World just out of curiosity when she came across an advert that looked very familiar. My reunion with my mother clearly hadn't worked out - she had advertised me in Nursery World for a third time. Nanny sent away for me again and I returned....

More than 30 years later a journalist from Nursery World contacted me to interview me about my history with the magazine. And here's the piece:

http://www.nurseryworld.co.uk/news/1032990/Nursery-World-advert-inspiration-memoir/?DCMP=ILC-SEARCH

January 29, 2011

What kind of family matters?

Previous | Index

What kind of family matters?

Is adoption the best thing for children in care? Precious Williams and David Akinsanya, who were fostered, reflect on their experiences

The Guardian, Saturday 29 January 2011

Article history

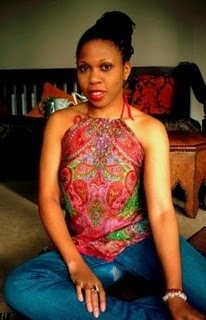

Precious Williams and David Akinanya discuss adoption. Photograph: Linda Nylind for the Guardian

Precious Williams and David Akinanya discuss adoption. Photograph: Linda Nylind for the GuardianThis week, Martin Narey stepped down as chief of Barnardo's, with a plea that more children should be adopted. He also criticised social workers who delay the process by searching for ethnic matches. David Akinsanya made a documentary about his experience of growing up in care, while Precious Williams wrote a book about hers. Both were fostered but never adopted, so what do they think of the latest pronouncement, asks Susanna Rustin.

David Akinsanya: My view is they've invested far too much in fostering and adoption when there aren't the people out there to do it. Yes, I would like to see more people come forward to be adopters, but they aren't there. The problem with the emphasis on adoption is that the rest of the care system becomes the Cinderella service. I would rather a child has stability in a children's home than be moved from one place to another. I grew up in a children's home and the first 10 years of my life were idyllic.

Precious Williams: I was in foster homes pretty much from birth. My mother wanted to get on with her career and she wanted me to be with a white family, so I was fostered by a white lady who was nearly 60. Nowadays there's no way social services would allow it, but this was the early 70s, and when I was about eight or nine my foster mum, who I called nanny, took my mother to court and won custody of me.

DA: My mum is still ashamed of my existence. She wanted to have an abortion actually, but my dad wouldn't let her. They'd broken up by the time I was born, so they put me in a private foster home. My mum is white and she met another man when I was about 18 months old and he said, "you've got to stop paying for this nigger child", so she stopped paying. The foster carers contacted the local authority and I was taken into care.

PW: I think our experiences growing up were too extreme. It was anything goes, they just didn't care. Maybe now it's swung back the other way?

DA: A lot of the problems in the care system at the moment are for mixed-race kids. That's where the policy of matching ethnic backgrounds is hurting. Being mixed-race myself, I feel it's perfectly acceptable for a mixed-race child to be in a white family.

PW: When I grew up in a small West Sussex town, everyone was white. I was so sick of being the only black person that I ran away to Peckham – and the black kids pissed themselves laughing at the way I spoke, the way I dressed, the state of my hair. I was listening to the Smiths and the Cure, what they called white music. And luckily I found it quite amusing, but I think some people could have found that traumatic.

DA: Part of the thing about going through the care system for me was that I was so ashamed to have been rejected by my parents. There's a part of me that wishes I had been at home with my father. I'm not very good with one-to-one relationships …

PW: I'm like that, I feel people will let me down. Maybe adoption would have given that security? There were other people in our town who were fostered, but it was usually something like, this person's mum was a teenage mum, or this person's mum is an alcoholic. But I would see my mum with a decent home and enough money … I spent a lot of years resenting my foster mum for not teaching me anything about being a black woman. Then when she was really old, she started talking about race, saying we had never really addressed it. I think I appreciate her more now. But the race thing loomed so large, and it took me so many years to deal with it.

DA: My dad passed away a number of years ago, but I've got letters from him going back to when I was five or six. It was never enough for me as a boy, I even went and smashed up one of his cars when I was 19 because I was so angry. But I made a documentary about my childhood and I was so lucky he got involved. I had a bike stolen and my dad turned up the next morning with a big grin on his face and a brand new bike. I was 30, but it made me feel like a child because I'd never had that. So we had eight really positive years before he died, but I spent a lot of my adult life angry with him.

PW: It's really sad, isn't it? I feel with my birth mother that it's a lot like that. She must have looked at the situation with me and her, and how horribly wrong it went, and it's almost like she just decided to walk away and start again with a new family. When I was 18 I got pregnant, and I had a daughter when I was still doing A-levels. I applied to university and was accepted at Oxford, and they made it clear I couldn't bring a baby with me, so instead of perhaps going to a different university I left my daughter to be raised during term-time by my foster mother's daughter, who I was very close to. So I didn't really step up and become the parent I wanted to be. It's easy for people to get into cycles, and I think that's really sad.

DA: I get so angry – we give families chance after chance after chance, particularly those who are involved with drugs or prostitution. The most important person in my life is a social worker, Jenny. She was my social worker from when I was nine until I was 15, and we've kept in touch. I am a foster carer and I take my foster children to her for Christmas, and when I'm there I feel like this is my family. She's someone who is really involved in my life. I try and publicise that because I think the problem for kids in care is they don't have any continuity. Children don't need two parents, they don't need them to be in a family, they just need somebody who's going to be there for them, who's going to be on their side, and I think that can happen through residential care, through foster care, and it obviously can happen in adoption as well.

PW: I think with my daughter, even though our foster family did a great job raising her, it might have been easier for her if she'd simply been adopted. That sounds really cold, and it wouldn't have been an easy decision, but if someone can't look after a child then they should have them adopted. I think stability and a very firm sense of belonging are absolutely crucial for a child's development, and more casual, short-term arrangements can result in confusion all round.

Precious: A True Story by Precious Williams is published by Bloomsbury

http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2011/jan/29/the-conversation-family-fostering-adoption

January 23, 2011

"I don't see you as black..."

Why do some people imagine they are paying a compliment if they tell a black person "I don't see you as black"?

Surely such a statement's as absurd as telling a man (of any race) "I don't see you as a man."

Below is a video of a man, a mixed-race man, discussing his feelings about race and why he doesn't see himself as being black/mixed-race at all. He says that "colour doesn't matter" and that there is no such thing as black culture.

Like me, this man was raised by white adoptive/foster parents in an all-white part of Britain. If I'd shared this man's sentiments I think my white family would have been ecstatic. I believe they hoped or even assumed I'd turn out like this man. Maybe that is what this intangible concept of "racial tolerance" is all about : giving up parts of yourself and feeling ultra-grateful when people accept the you that you have chosen to become.

I've also covered this issue in the February issue of ELLE magazine in South Africa. Check it out :)

November 30, 2010

Is love enough?

Earlier this month UK Children's Minister Tim Loughton vowed he'd relax rules around transracial adoption, making it easier for white families to adopt black and other minority children.

But can a black child really thrive in a white home? Is love enough? And why are so many white celebrities adopting African-origin children......?

This question was answered brilliantly by Cynde. Cynde is white and American, fabulous and also an adoptee herself, and she has gone on to adopt two black daughters. She also happens to be my Aunt, through marriage, and we first became acquainted when she contacted me after reading my memoir Color Blind, which of course deals with transracial adoption. Here is what Cynde has to say on the subject:

"As a trans-racial adoptive parent my answer is yes, color does matter in parenting. Especially when adopting across color and cultural lines. To pretend there is no difference serves only to help the parent stay in denial of a color conscious society and perhaps their own racial prejudices. It also sends the message to the child that race as a subject is off limits and more subtly that perhaps the parent is uncomfortable about their child's color.

As a white parent of two black daughters I understand that my experiences are and will be different. If I'm aware of that I can foster relationships with friends, mentors, role models, teachers, neighbors and church members who's racially experiences more closely match those of my children. Having said all that, this is just the beginning of helping your adoptive child have a healthy racial identity. But acknowledging that as a member of a different race from my child I cannot fill in all the gaps in my child's identity is a start."

The odds...

I was just thinking about how the things and situations and people we quickly write off as being dysfunctional can actually be nurturing in their very own way.

One of the recent reviews of my memoir said something like "Against all the odds she went on to become a writer". But I think it is because of "all the odds" that I achieved my ambition of becoming a writer.

I was raised by an elderly, very, very eccentric white woman who called me 'coloured' and seems to have wanted to foster me mainly because I reminded her of Topsy in the novel Uncle Tom's Cabin. The situation looked - and was - odd (huge understatement). But this same woman also spent her state pension buying me endless books and writing paper and pens and paints even when it meant she couldn't afford to pay the electric bill. (Which meant that her own grown-up children often had to help her out with the household bills). She introduced me to the works of Chaucer and Dickens when I was little more than five years old.

As a young kid I was forever making excuses as to why I couldn't go into school that day (my attendance levels were almost laughable some years). I just wanted to stay home and write short stories and poems and read books. A functional parent would have made their child attend school regularly. Instead my foster mother indulged my ridiculous excuses for not going into school that day and often let me sit at home writing, daydreaming, reading my poems out loud to her. She acted as though every verse I wrote was on a par with Shakespeare.

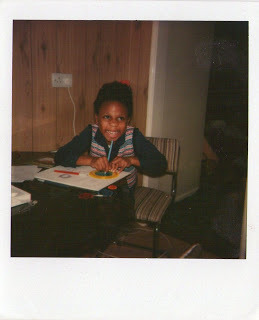

Bunking off from school again?

My foster mother would tell everyone who'd listen that I was going to be a published writer one day, stating this as if it were a fact. I'm sure many of our neighbours on our council estate laughed behind her back and thought that both my foster mother and I were utterly out of touch with reality. Truth be told, I think she prided herself on being out of touch with reality.

When I was about ten I was still writing my mini-novels in exercise-books in felt-tip pen but I felt a bit frustrated that my foster mother was the only person who read my words. "How much longer till I'll be a published author?" I asked her. "Well you'll need a typewriter first," she said. She got me a typewriter for my twelfth or thirteenth birthday. I spent hours and hours typing up my latest work-in-progress and sent it into a major publishing house who were sweet enough to send me an encouraging, hand-written rejection note. Twenty or so years later, when my agent submitted my memoir-in-progress, that very same publishing house made an offer to buy my memoir Precious, A True Story (although in the end I signed with Bloomsbury)!

My foster mum died in 2009, in her mid-90s. Just a few days before she passed I'd told her I was about to have my first book published. She said: "I'm not at all surprised, darling. It will be the first of many."

November 29, 2010

A model example by Precious Williams, Daily Mail

by PRECIOUS WILLIAMS, Daily Mail

Aimee has enjoyed huge catwalk success

Aimee Mullins is munching French toast at her favourite greasy spoon in Manhattan's West Village. She's tall, slim and blonde with wide, hazel eyes, wearing Stella McCartney cords and high-heeled sandals.

It's only when she hoists a leg up on the table and reminds me that it's fake, that the illusion of physical perfection is shattered.

Aimee, 25, had both legs amputated just below the knee when she was a year old. She was born without a fibula in her lower legs, possibly caused by her mother taking antibiotics before she knew she was pregnant.

The next few years were spent in a wheelchair, and doctors warned that she would never walk. Unfazed, Aimee taught herself to walk with artificial legs and by the age of 10, she was also running, skiing and playing softball.

"My parents never told me that I couldn't do something," she says. "They expected me to excel." And she did.

Aimee did her internship at the Pentagon, broke world records in the 100 metres, 200 metres and long jump at the 1996 Paralympics, and has been voted one of People Magazine's 50 Most Beautiful People.

Catwalk sensation

But when she was chosen by Alexander McQueen to appear on the catwalk in his 1999 London show, she suddenly found herself on the front pages, being hailed as the "new, disabled supermodel". She loathed the label. "I hate the words 'handicapped' and 'disabled'. They imply that you are less than whole. I don't see myself that way at all."

Photographer Nick Knight had called Mullins after seeing her on the cover of a design magazine, showing off the metal legs she wore to compete in the Paralympics. "He asked if I would be interested in doing a shoot with him and Alexander McQueen.

"They ended up shooting me topless, but it was all done very tastefully and I wasn't embarrassed, partly because I thought it was unlikely that my parents would ever see it. I got on really well with Alex and he asked me to model in his next show."

Aimee strutted down the catwalk on intricately carved wooden legs that were designed by McQueen to look like long, ornately detailed boots.

"It was so exciting, I felt just like one of the other models. The aim wasn't to make a big statement or anything. Nobody in the audience knew that I didn't have legs until after the show - then the newspapers just went crazy."

McQueen was criticised for turning his fashion show into a freak show - he was even accused of exploiting Mullins's disability. "That wasn't what it was supposed to be at all," says Aimee.

"Alex was just trying to expand the idea of beauty, but I ended up with reporters camping outside my home and I had to stay in a hotel to escape them."

She is thrilled to be coming to London next week to officially open Bodycraze month at Selfridges, where real women are invited to take part in a series of events that will, hopefully, make them feel good about themselves, not dread the changing-room mirror.

Challenging perceptions

"Part of the reason I wanted to model was to push the boundaries and challenge the perceptions of what a beautiful body is supposed to look like. Why should I feel any differently about looking good than anyone else?"

Like any successful model, Aimee is deluged with designer freebies. But unlike other models, she has to buy a new pair of legs before she can slip on that latest pair of designer shoes.

"Prada has just sent me some fabulous shoes with five-inch heels. But none of my six pairs of legs will work with such high heels. I'm going to have to get a new pair before I can even try the shoes on," says Aimee.

Her collection of legs is designed by Bob Watts, a British prosthetist, and includes a shapely silicone pair and the carbon-graphite stems she wears for sprinting. "Each pair of fake legs is designed to be worn with a different heel height. I take the shoes to Bob and he makes me legs to go with them," she says.

"I trust him to give me the ankles that I deserve. Most people are only missing one leg, so it's easy enough to model the fake leg on the one that is already here. But with me, Bob has to start from scratch.

The legs that I have made are far more perfect than the ones nature would have given me - my mother's side of the family have awful legs. It's very difficult going through those metal detectors at airports.

My legs contain metal and they always set the beeper off, but they look so real, with follicles and freckles, that nobody believes me when I say they're fake."

Aimee jokes continuously about her fake legs, but you can't help wondering whether there is some bitterness lurking beneath the good humour. "Not at all," she insists. "I remember being angry when I was about 12 and miniskirts were all the rage, but apart from that, no.

"I haven't had an easy life but at some point you have to take responsibility for yourself and shape who it is that you want to be. I have no time for moaners. I like to chase my dreams and surround myself with other people who are chasing their dreams, too.

"You have to be fearless and go after what you want and that often means humiliating yourself and not being afraid to fail or be laughed at. I call that the 'So what' factor. You think to yourself: 'So what if I fail? So what if I get laughed at'"

Happy childhood

She attributes her fearlessness to a happy, supportive childhood. "We grew up in Allentown, Pennsylvania and I was surrounded by aunts and uncles and cousins as well as my mum and dad and brothers, Thomas and Brian.

"It was like being in a little nest of a family - it was very nurturing. None of them ever made me feel that I was different or that I couldn't do whatever I wanted to do. I was just an ordinary, capable kid."

That attitude stayed with her as she grew up, and she says she got over any complexes about herself years ago. "It takes some women till their thirties, even their forties to realise that what makes them beautiful is not what makes them the same as everyone else, but what sets them apart.

"I've always felt that I was pretty, but ask the average man whether he could be attracted to a woman who had no legs from the shin down and he'd almost certainly say 'no way'."

She has a long-term boyfriend, and has never struggled getting a date. "When men see me in the flesh, they do find me attractive, and I'm always being chatted up. I get complimented on my legs a lot - I always tell the guys I'll pass the praise onto my leg designer.

"That shocks them. But I'm just trying to show that having no legs doesn't make you less feminine, less beautiful or any less of a woman."

Read more: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/femail/article-179284/A-model-example.html#ixzz16flGqrOA

August 16, 2010

Interview with Precious Williams by Tricia Wombell

Precious William's memoir Precious: A True Story has just been published by Bloomsbury. I am pleased that she agreed to answer my questions about her book and the books that have inspired her.

Thank you Precious.

Your book is a memoir about your being privately fostered to an English family in West Sussex...

August 7, 2010

My long journey home... by Precious Williams

I was recently commissioned by the Guardian newspaper to write an article on the theme of family, looking at my own journey to finding a sense of family. As I sat down and pondered on the concept of family I realised just how complicated that theme, even that very word, 'family', had been for me until very recently. My foster family's not perfect but they do love me and in many ways they have been extremely supportive and caring. I literally ran away from them and grew more and more...