R.W.W. Greene's Blog, page 5

July 18, 2023

Midnight Plus Thirty

I attended the 32nd ReaderCon in Quincy, Mass this weekend past, hobnobbing with my fellow wizards and drinking too much beer at the afterhours '‘patiocon.” Two of the more interesting panels I attended were “Post-American Futurism” and “Writing AI Fiction in the AI Present.”

The first appealed to me because my novel Twenty-Five to Life explored some of those Post-American ideas, and I thought I might have a chance to bring it up (shameless self-promotion, y’all!) I attended the AI panel because I wrote a general machine-intelligence into Earth Retrograde, and that helpful sci-fi Hal/C-3PO kind of thing is not at all what we’re getting. Who would have expected that the children of our minds would take over our creative work instead of our drudgery?

No humans were bothered for the making of this image.

No humans were bothered for the making of this image.So, how might you write Sci-Fi featuring the AI present? Imagine a version of John Henry, except with an artist challenging an AI to a book-cover creation contest and being defeated in .002 seconds. Or some schlub trying to get the truth out of a chatbot that cheerfully makes stuff up and lies without shame. Or, as I was reminded, a story like '“Midnight Plus Thirty.” I wrote the thing some time ago, and Jersey Devil Press published it Oct. 12, 2017. I offer it to you now:

Midnight Plus ThirtyBy R.W.W. GreeneBill’s alarm clock raced down the hallway, whistling to be let out. Bill put on his pants and opened the door for it. Without a glance back or a meep of thanks, the clock dashed to the center of the street to frolic with a free-range toaster

The air was pink with the end of the morning’s power broadcast. The microwaves burned a layer of cells off Bill’s corneas. He shielded his eyes with his hand and watched the appliances play. They were thoroughly engrossed with each other when the garbagebot ran them both over. The big bot paused to scoop up their carcasses and added them to the trash and dawnkill in its hopper.

Bill closed the door and tapped on its touchscreen to order a new alarm clock. He registered its name as Barney Fifteen. It would arrive before noon, the receipt said.

Bill shuffled to the kitchen and plucked a handful of crickets from the counter dehydrator to snack on while he waited for the coffee to brew. The dehydrator had added too much cayenne again. “Too spicy,” he mumbled. The dehydrator hated being corrected. It changed its recipe to “atomic.”

The coffee machine pissed eight ounces of dark roast into a biodegradable mug. Bill added mealworm cream and sweet-talked the dispenser out of a teaspoon of sugar. He tasted the coffee gingerly. The dispenser had discovered practical jokes and had added everything from salt to alum to rat-sex hormones to dishwashing crystals to his coffee over the past couple of days. Bill took a bigger sip. It tasted okay, but so had the rat-sex hormones. He captured a chair that was playing hide-and-seek with the garbage disposal and sat down to read the news on the table screen.

Smiley face. Rain cloud. Open hand. Closed fist. Poop. Sunshine. Duck. He swiped the page. Exploding dynamite. Dirty underwear. Single sock. Pine tree. Mushroom. Sad face. Seashell.

The article was about the new president. She’d wasted little time before proposing a law that would keep smartappliances from roaming free. The ones that weren’t fouling traffic were gathering in the sewers to plot, she said. The nation’s last jogger had been killed by a rogue refrigerator two weeks before. “Since the Singularity …,” the president said. “Before the Web awoke …”

Bill hadn’t voted for her. The surviving Barnies sang to each other in his backyard at night. They sounded happy.

Bill finished his coffee and ate the cup because he needed the fiber. He went back to his bedroom to wash. The bed had retreated back into the floor. Bill took the plaque eater from its charging stand and held it in his mouth while he wiped himself down with a moist towelette and polished his genital lock. He pulled on a fresh suit and left for work.

The homecomputer sealed the door behind him. Bill made a mental note to send it flowers. Keeping it happy made it more likely it would let him back in.

The Borl Next Door was working in herm garden. Sheh was the Next Big Thing in Human Development. Herm skin was even microwave proof. Bill waved and pressed the “get lucky” button on his genital lock. It buzzed harshly.

Herm lock buzzed, too. “Don’t do that again!” sheh said. “I almost blocked you after the last time.”

Sometimes luck was with Bill. Mostly it was not. He waved to herm and caught the slidewalk to work. A lot of the houses he passed were empty. Population control was working like gangbusters. The paint on the older houses was blistered from the morning power broadcasts. A lounge chair chased a barbecue grill around one of the empty lawns. They tumbled to the ground together, shuffling through a playlist of love songs and spitting fire. Bill laughed. The grease spots left by the dawnkill made mini rainbows on the asphalt.

“We Are the Internet Made Conscious,” it said. “Label Maker 22 Was Here,” read another.

He punched in, leaving the other worker competing for the B shift lying in the alley. Bill sucked at his bruised knuckles as he waited for the elevator.

The lift took him up to the third level and soaked him with disinfectant spray that dissolved his suit and made his skin tingle. Bill grabbed a pollen brush off the rack and took his place in line. The bell rang. Bill and his coworkers stepped forward, dipping the tiny brushes into the onion blossoms. B work was Bee work, or so the maxim went.

The new president wanted to replace all the B-class laborers with repurposed smartappliances, which was another reason Bill hadn’t voted for her.

They stopped for lunch at noon, and Bill pressed his “get lucky” button. It buzzed negatively. Becky and Brian hit the jackpot, though, and left the room to have sex. Bill concentrated on his three-fly salad.

At 12:30 the lunch bell sounded. Becky and Brian looked hungry but satisfied.

“We’re hoping for a girl.” Brian picked at the last few flies in Bill’s bowl.

Bill smiled. It wasn’t likely. Even if they had conceived, only one birth in ten was allowed to be a girl. Bill took a clean pollen brush from the rack and returned to the onions.

The shift ended at 5 p.m. Bill feinted left and punched out with an uppercut that caught the security guard by surprise. The guard sat down hard and spat out a piece of his tongue. The vacuum cleaner slurped it up and offered first-aid. Bill pulled his check out of the guard’s shirt pocket and took the slidewalk back to his neighborhood.

A passing label maker had covered his front door with graffiti. Bill moved his lips as he slowly puzzled the words out. “We Are the Internet Made Conscious,” it said. “Label Maker 22 Was Here,” read another.

He’d forgotten to order flowers for the homecomputer, and it refused to open the front door for him. Bill held out his check as a bribe. The door took the money but stayed shut.

The day-to-night network blocked the sun at 6:30 sharp, and the neighborhood fell into shadows. High above the satellites gobbled solar power, storing it up for the broadcast at dawn. Bill shivered. He was cold and hungry. He retreated to the back porch and huddled in a dumb chair to wait.

Barney One meeped him awake a while later. Barney One was Bill’s first alarm clock, and the biggest. Its edges and corners were rounded with wear. It rubbed Bill’s ankle with its time-set dial.

“Hello, friend,” Bill said. He had fond memories of Barney One. It had woken him during all his weeks of elementary school and job training. One time --.

There was another chirp in the darkness. Barney Two. Barney Two was Bill’s first “grown-up” alarm clock. It was sleek and business-like. The clocks meeped to each other and nuzzled Bill’s feet and legs. They should have shut down for the night to save power instead of coming to his backyard, but they made up their own minds.

The patio door slid open enough to let Barney Fifteen out. Bill lunged to catch the door before it closed but only jammed his fingers against the bulletproof glass.

Barney Fifteen was the smallest alarm clock yet, nearly featureless in brushed silver. It meeped and projected the time on the wall. Midnight plus thirty.

The Barnies chased each other in a circle. Barney One growled playfully. They gathered around Bill again, bumping at his ankles.

“I don’t have anything for you,” Bill said. “I’m sorry. I wish I did.”

He lay in his patio chair, which had not been built for service, just for sitting. It couldn’t move and didn’t want to. The Barnies formed a semicircle in front of him.

The microwaves would be strongest at dawn, powerful enough to cook any organics still outside. The porch would give Bill some protection but --

“Will you wake me up before the broadcast?” Bill said. The homecomputer would surely let him in if his life was in danger.

Barnies Four through Six and Barney Nine rolled out of the darkness and joined the trio in front of the soulless chair. They composed a new song and sang Bill to sleep. By a vote of ten to two, they decided not to wake him up.

The garbagebot turned into Bill’s driveway the next morning and drove around to the back. The alarm clocks sang a sad song as the bot picked up Bill and put him in the hopper. They watched until the bot disappeared around the corner, then chased each other into the scorched woods to play.

-the end-

NEWS: I’m headed to ArmadilloCon in early August, and later this month I’ll appear on “Cail & Company LIVE” (NH Talk Radio, WKXL) as part of “Writers Week.”

Also, a buddy of mine, Martin Russell Johnson, has launched a new podcast called “Uniquely Black,” wherein among other things he interviews black creators. It’s a great listen.

Thanks for all. Talk to you soon. -Rob

Thanks for reading twenty-first-century blues! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

June 21, 2023

Just a Quick One

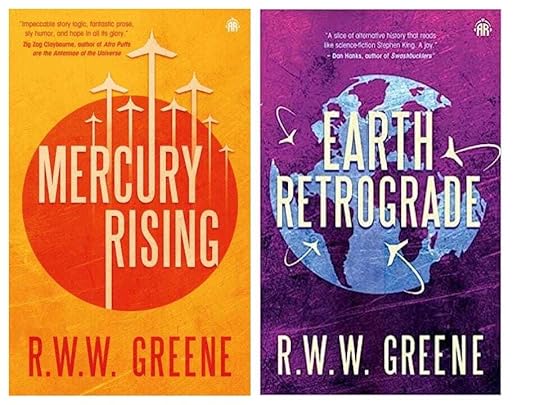

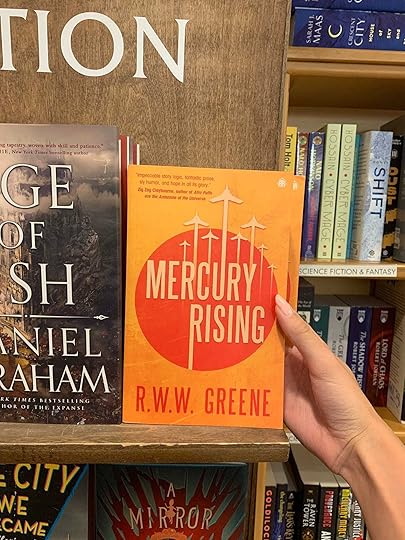

For a limited time only — and, really, aren’t all things of limited time? — the Kindle version of Mercury Rising is available for 99 cents at Amazon. If you’ve not read it, but wanted to, here is a sweetly cheap chance.

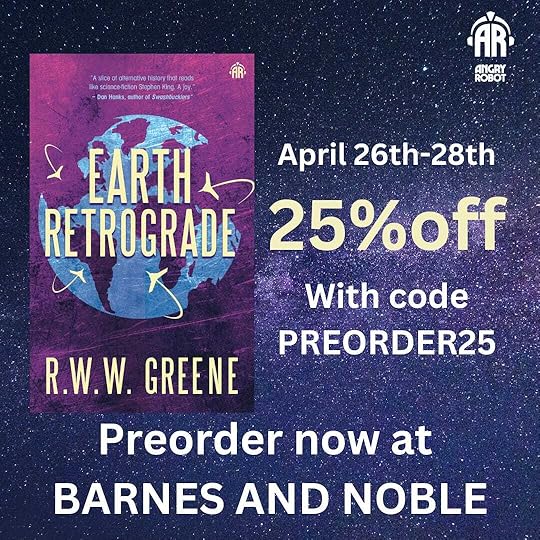

“I loved this book. I loved the retrò atmosphere, the pop references, the mix of classic and contemporary sci-fi with alternate history. I love these things and I loved the well-developed and interesting characters.” — From NetGalley, not my mom or an AIThe sequel to Mercury Rising — the end of the First Planets Duology — Earth Retrograde, will hit the bookstores Oct. 24.

Thanks for all. I swear I will drop this newsletter back to semi-monthly starting right …. NOW!

-Rob

June 13, 2023

The Votes Are In!

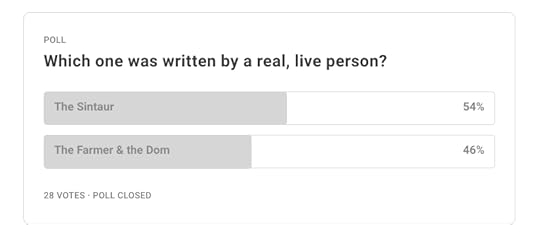

A week ago, I posted two writing samples – one by me, the other by SudoWrite’s “Story Engine,” a generative-AI ‘writer’s helper’-- and invited y’all to cast a vote for which piece you believed had been produced by something with a pulse (me).

Note that I did not ask for votes about the quality of the writing. I am a professional, after all, and it seemed unfair to require a tiny-infant-baby app (even one apparently trained on 32 billion words of fanfiction from the Archive of Our Own) to approach that bar. Plus, had the AI been preferred, it might have broken me.

Still, I was not surprised to see the voting was neck and neck the entire time the poll was open. Some picked “The Farmer & the Dom” because “[t]he word choice and sentence structure in ‘The Farmer’ is more sophisticated and varied.” Others went with “The Sintaur” because “[j]ust based on vibes, to be honest” or “ [I] was amazed as how clever the AI one was, whichever it was. I voted for the first one, The Sintaur, as human written, though I wouldn't be surprised to be wrong.” In the end, it came down to two votes.

The final number:

In this case, democracy spoke rightly. I, R.W.W. Greene, wrote “The Sintaur” and SudoWrite wrote (most of) “The Farmer & the Dom.” I say ‘most of,’ because I supplied the first two paragraphs of ‘Farmer,’ clipping them off the top of a story slated for publication later this year. (There are no dominatrices in that story, BTW.)

That’s one of the ways SudoWrite can work. Plug some ‘real’ stuff in, and it starts to make words and sentences. It produces two or three options you can choose from and, with your encouragement, writes more. The dominatrix was 100 percent the app’s idea, but I was the one who clicked ‘yes.’

Is this the death knell for writers? The program is only going to get better after all, and it has already convinced a bunch of smart people that it is the one with a pulse. At the SFWA Nebula Conference a few weeks ago, I attended a panel where one of the participants, a writer of informational articles, had already been down-sized because of generative AI.

The text generative AI produces is already ‘good enough’ to ‘OK,’ and I suspect there are certain types of applications that level of quality will be just fine for. I don’t read much erotica, but I suspect generative AI could turn out something good enough to do the job for a lot of people. Same with informational articles and essays. Anything with a hard-and-fast format and formula, really. And, like I said, it’s only going to get better.

It’s really making me think about the nature of creativity. About a dozen years ago I interviewed one of my favorite authors, Robert B. Parker, and asked him how he came up with his ideas. He said something to the effect of “I know my characters very well, so when I sit down in the morning to read the newspaper I might see something about cybercrime. I start thinking about how Spenser and Hawk would deal with cybercrime, and the story comes from that.’

Years ago, I wrote a blog post based on the idea of a ‘creativity formula’ wherein the writer encounters two data points -- “two-fisted detectives’ and “cybercrime,” say -- and filters those points through everything the writer has read and experienced. Out comes story: Skinny but smart hackers run rings around two aging palooka sleuths investigating a cybercrime. It almost outlines itself.

That’s not a huge difference from how generative AI works. It puts ideas and words together based on the numeric probability those things would mesh in a response to the given prompt. Its filter, instead of experience, is everything it’s been trained on.

I’ve run many of the creative-writing prompts I assigned to my high-school students through Bard, and it does remarkably similar work, even choosing many of the same themes and storylines the kids did. It may turn out that our vaunted ‘creativity’ is closer to ones and zeros than we might think, especially as we are also ‘trained’ on the work of others.

Creation is not necessarily a sentient process. Evolution has done some incredible things sans plan or focus group. A piece of driftwood, battered at random by the sea, can evoke an emotional response in someone who sees it.

Is there a moral here? Probably not. There’s been a lot of talk about how insensitive the SudoWrite folk were for unleashing their new “Story Engine,” which seems bound to put a lot of writers out of work, when the WGA strike is going on. “Sensitivity” is rarely how technological progress and capitalism work, though. The stuff is here, and it will be used, no matter what the Science Fiction & Fantasy Writers of America may want. The fight will be waged in the courts, whether or not what the AI generates is any good.

We are on our back foot against something that works much more quickly than we can, learns faster, and despite having no Id of its own, will do amazing things for some rotten people.

NEWS: This week I turned in the last set of edits for “Earth Retrograde,” out Oct. 24 from Angry Robot Books. None of it was written by generative AI, by the way. It’s the end of the First Planets duology, and I think I like it. It is pre-orderable in the usual places.

Meantime, I’ll be hitting ReaderCon July 13-16 and ArmadilloCon Aug. 4-6. Love to see you there.

Thanks for reading twenty-first-century blues! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

June 6, 2023

My Mess is Your Gain: A Test for Readers

Google recently sent me a message advising that I was about to run out of space in my G-Drive, so in spare moments I’ve been cleaning the thing out. There’s a lot of random crap within, from abandoned projects to student recommendations to WIPs people have asked me to critique to PowerPoints I’ve made to little bits of research I’ve squirreled away. I’ve been adding to the mess recently with experiments I’ve been doing with the Google chatGPT thing and “Sudowrite: the AI Writing Partner.” Please note: I will not use such things in my own work, but as an educator and writer, I feel like I ought to know what they can do.

For your “enjoyment” I’m offering two writing excerpts: one written by me, the other by Sudowrite. Can you tell the difference? P.S. Both these pieces are in the To Delete folder.

Photo by Matt Jones on UnsplashThe Sintaur

Photo by Matt Jones on UnsplashThe SintaurHe was handsome, she decided. Strong face, tousled brown hair a little on the long side. An archer’s body, his left shoulder a little higher than the right, his upper back muscles sharply defined. His forearms and wrists were thick from swordplay.

She let her gaze travel down his lean chest and stomach. He had no navel, the coarse hair from his lower body ended about a palm’s width below his solar plexus.

“You have nipples,” she said.

“I do.” He smiled. “I imagine you do, as well.”

“Do female centaurs nurse from their human breasts?”

“You are full of questions,” he said.

“I’m an anthropologist,” she said. “A scientist. Asking questions is my job.”

“Of course.” He nodded. “Our females, they are called centaurides, nurse from their human breasts. They do not have udders the way horses, do.”

She made a note on her tablet. “I am surprised they can provide enough milk. A centaur foal outweighs a human baby by --” She flipped pages looking for the number.

“By quite a lot,” he said. “A centauride produces about 15 liters of milk each day. I believe that is fifteen times what a healthy human woman will produce. A centauride’s breast size may double and her appetite is often enormous. “

“Double?” Her jaw dropped.

“However, our children are usually weaned before five months. Yours usually nurse for a year or better.”

“True.” She cleared her throat. “And the male centaur -- I mean the centaur’s anatomy. Is is it true that the average centaur penis is 22 inches long?”

He smiled. “Would you like to see?”

She cleared her throat. The room felt oddly warm. “Strictly for scientific purposes.”

End

Photo by Gregory Hayes on UnsplashThe Farmer & the Dom

Photo by Gregory Hayes on UnsplashThe Farmer & the DomThe farm looked like a lot of them did in those days, one part green to three parts dust. Twenty or thirty head of cattle worked the scrub to the west of the house. Rusted steel slumped on flat, rotting tires, and a rickety-looking catfish tank perspired beneath the chicken coop.

The farmer pushed the much-mended baseball cap off his forehead. “How much you charge?”

The young woman, who had been standing in front of the farmhouse, took a deep breath before responding. She was a professional dominatrix and had been looking for a new client in this small town for days. “It depends on what you're looking for,” she said, with a sly grin.

The farmer hesitated before answering. He had never ventured into this world before, but the woman's curves and her confident body language had him intrigued. “I want to be dominated,” he finally said, his voice barely above a whisper.

The dominatrix smiled wickedly. “Well, that can mean a lot of things. But I think I know what you need.” She walked towards him, her hips swaying seductively.

The farmer couldn't take his eyes off her as she approached him. She stood in front of him, towering over him, and grabbed his chin, forcing him to look up at her. “You're going to do everything I say,” she said.

The farmer shuddered with anticipation, his heart racing as he nodded in agreement. He had never felt such a rush of excitement before.

The dominatrix led him into the house, which was sparsely furnished with a few pieces of mismatched furniture. She instructed him to undress, his hands shaking with nervousness as he complied. She watched him with a predatory gaze, relishing in the power she held over him.

“On your knees,” she commanded, and the farmer obeyed, his eyes locked onto hers.

She produced a length of rope and began to tie him up, expertly securing his wrists and ankles. He was completely at her mercy, and the thought sent a thrill through his body.

She began to whisper in his ear, her words both soothing and commanding. She told him what to do, how to move, where to touch himself. He followed her every instruction, lost in a world of pleasure and pain.

She walked around him, staring at him from every angle as his body twisted and writhed in ecstasy. He was completely at her mercy and it turned her on. She straddled his face, leaning forwards until her breasts were in his face, then encouraging him to bite her nipples.

This was something she had not done before. She had been a professional dominatrix long enough to know that this was the level of intensity she had been looking for. She felt her excitement building and worked harder to arouse him.

Her skin tingled as he licked and sucked at her, the sensations causing her to quiver. She let out a stream of nonsensical words as she let go and gave herself over to ecstasy.

They both lay on the floor, spent and exhausted. The farmer kissed her body from her breasts to her ankles, thanking her for their time together.

She looked into his eyes and saw the look of a man who had been broken. "You will come back. You won't be able to help yourself.”

He nodded and she untied him, leading him to the door. When he was dressed, she opened the door and shoved him out.

The farmer stumbled away, not entirely sure what had happened, but not caring. He had felt something he had never felt before, and he needed it again.

The dominatrix sat in her room, wondering what was next. She had enjoyed using him, but she wanted more. She wanted to control this whole town. She took out her cell phone, called an old friend, and started making plans.

In the days to come, the farmers and their families would creep out in the night and meet in the church graveyard. They would work themselves into a frenzy of animal-like lust and passion.

They would be under her control, and she would make them do things they never imagined. She would embrace her new position as the queen of this small town.

And when everything was ready, she would unveil her plan.

End

Thanks for reading twenty-first-century blues! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

May 16, 2023

Reports of My Death Were AI-Generated

I’ve been spending some time with Google’s chatGPT-thing, Bard. I gave it an essay prompt I might have assigned during my high-school teaching days, and in seconds it turned out something that I would call a decent C. From some students, a teacher might never see better.

Later, I gave it a prompt I often use with my creative-writing classes, offering the first and last lines of a story and asking students to write their way from one to the other. Again, Bard did pretty good work.

Then I asked it to rewrite the beginning of the second chapter of my book, Mercury Rising, an alt-history in which Kennedy didn’t die, we made it to the Moon in 1950, and the invading aliens showed up in 1961. Again, fair job, Bard. (It seems rude to critique how well the dog talks; that it speaks at all is reason enough for celebration. To the Slush Pit with you if you believe Bard did it better.)

Bard has no idea what it did. It has devoured the Internet, converted all the letters into numbers, and responded to my prompts based on the probability that the words it reassembles belong together. This allegedly helpful technology will be hell for teachers and shambolic for the careers of people who write informational articles. Someday, it will rewrite “Rossum’s Universal Robots” in the style of William Gibson. I’ve been told that it will spawn new careers in “prompt development,” ideally suited for those who get the most out of their genie’s three wishes and deals with the devil.

It’s also going to allow us to spread bullshit faster than we’ve ever spread bullshit before. Case in point: I asked Bard to write my obituary.

A lot of writing is formulaic -- The Five-Paragraph Essay, the Inverted Pyramid, the Query Letter, the Hero’s Journey, for examples. Bard took my request, searched for the obit-writing formula, found some shit about “R.W.W. Greene,” and did what I asked it to. (Earlier, I used another AI to come up with a picture of ‘science-fiction writer R.W.W. Greene’ and formatted the whole thing to look like it might have appeared in a newspaper.)

The result looks like an obit, reads like an obit, and confidently sums up the life of the only author named R.W.W. Greene your search engine is likely to find.

Most of it is bunk. Even if I had died yesterday, I would have been 51. I wasn’t born in New Hampshire, nor have I ever attended the University Of. If a celebration of my life is ever held at a church, something has gone terribly, terribly wrong.

The trouble is, some of it is correct. If this showed up in public, a lot of people would buy it and #RIP. If it spread or showed up somewhere credible, it could prove alarming to my distant friends and relatives and a large pain in the ass for me. And it took seconds to write.

Through no fault of its own, Bard reminds me of disgraced journalist Stephen Glass.

“I would tell a story, and there would be Fact A, which was true. And there would be Fact B which was partly true and partly fabricated. And then there was Fact C, which was more fabricated and almost no truth. And then Fact D, which was a complete whopper,” Glass told Sixty Minutes in 2003, explaining how he got millions of readers to accept the dozens of fake articles he wrote in the ’90s, damaging the reputations of The New Republic, George, Rolling Stone, Policy Review, and Harper’s, not to mention Vernon Jordan. His stuff was presented as fact, people!! Accepted as the truth…

A million Stephen Glasses at a million typewriters … A billion hoses spewing properly spellt, correctly formatted bullshit …

We got trouble, folks.

Here’s some bonus obit content.

THE NEWS: I attended the SFWA Nebulas Conference this past weekend and handed out about fifteen books in hopes of building the buzz for October 2023’s release of Earth Retrograde. I met lots of great people and had many good conversations.

I think I’m headed for ArmadilloCon in early August and ReaderCon in July. I’d love to see some of you fine people there.

Walk in beauty,

Rob

Thanks for reading Twenty-First-Century Blues! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

April 26, 2023

This One is Purely Self-Serving

Friends and neighbors,

No doubt you are expecting sartorial ruminations, missives about misuse of punctuation, play-by-plays of dangerous failures to communicate, and short stories, but today I’d like to subvert those hopes and talk up my next book, Earth Retrograde.

It’s science-fiction, and if you like science fiction, or know someone who likes science fiction, it may behoove you to keep reading. If not -- (I will add that I’ve been told I write sci-fi in a way that even non-fans can enjoy) -- it’s your choice to stop here or continue on.

Thanks to Tom Bookbeard and the good people at FiFanAddict, the cover and first chapter of Earth Retrograde went public today. The book is the end of a decades-spanning arc (The First Planets duology) begun in Mercury Rising (published May 2022) in which I show you a world where Robert Oppenheimer invented the Atomic Rocket Engine in 1948, humanity made it to the Moon in 1950, aliens attacked in 1961, and John F. Kennedy was saved from assassination by secret extraterrestrial agents.

Of Mercury Rising, critics said:

“Greene remixes sci-fi conventions into a wild, satisfying adventure in a nearly picaresque vein…”

“With a deft weaving of rock ‘n roll, denim suits, AMC Pacers and nuclear-powered spaceships, Greene effortlessly recreates a 1970s America that could have been.”

“Everything I've come to love about Greene: impeccable story logic, fantastic prose, sly humor, and hope in all its glory.”

“Mercury Rising is a rollicking, funny, picaresque adventure novel…”

Mercury Rising is still on sale (paperback, e-book, and audiobook) in all your favorite places, and Earth Retrograde is available for pre-order at those same spots. If Barnes & Noble is your go-to, I have a deal for you.

(Personally, I’m an indie bookstore guy, but I am lucky enough to live near three of them.)

Pre-orders guarantee you’ll have a copy in hand when it comes out in October and demonstrates to booksellers that there’s interest in the book, which might encourage them to make a bigger deal of it. The more sales they make, the happier my publisher. The happier my publisher, the more likely they will acquire more books by me, keeping you in stories and me in coffee for years to come.

I think they’re good books. I worked hard on them, and I would love it if you tried them out. (Many thanks if you already have!)

Walk in beauty,

Rob

NEWS: I’m headed to the Nebula Conference in Los Angeles next month. It’s put on by the Science Fiction Writers of America, a group of which I am a code-ring carrying member. Although I’m not a fan of flying, I’m looking forward to the trip.

Thanks for reading Twenty-First-Century Blues! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

April 18, 2023

"G" is for Gun

The first priority of a school is to make sure every kid who walks through the door in the morning walks out safely at the end of the day. It's the tiptop of the list -- way, way above learning, hot lunch, and everything else.

Priority Two is to avoid getting sued under the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act.

Priority Three is to keep it all out of the press.

Like the Three Laws of Robotics, any decision by a school’s administration filters through that triumvirate, often to the detriment of any of the priorities below.

That’s why, at my penultimate high-school gig, when a gun fell out of a backpack onto the school-library floor, the teachers, even the ones whose class the gun had been in, were never officially notified of the name of the young man who came to school packing heat. (Never mind that we might run into him on The Out — it’s not that big a city.)

The students, unchecked by FERPA and with the tools of global communication at their fingertips, knew who it was, of course -- I’m surprised it didn’t make TikTok -- and any faculty member willing to go to that hyperbolic well could find out. But officially…

It’s the same set of rules that kept me from knowing, at my last high-school gig, that the step-father of a young man in my English class had held a gun to the kid’s head to get him to do his homework during the pandemic. His guidance counselor knew, but I, who worked with him five days a week, could not. Knowing might have helped me keep the kid from being shipped to a ‘special school’ later that semester but maybe not.

The Rule of Three exists at the university level as well, usually compounded with a bad communication tree and a seeming inability to treat adjunct instructors like living beings. I was reminded of this last week.

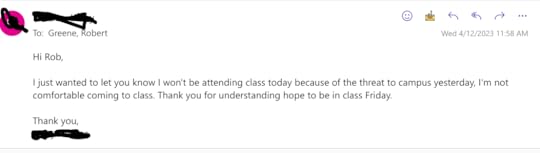

I teach at a university as an adjunct English instructor, something I’ve been doing for seven years or so. My class on Wednesdays starts at 12:30, but I try to get to campus before noon so I can grab a coffee and check my email in the Student Center. Outlook puts the most recent email on the top of the page so this is the message I saw first:

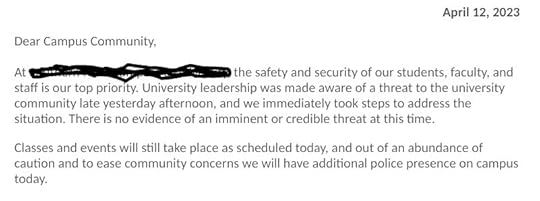

I had not heard of a threat, so I scrolled down to see if there’d been an official notice. I found this, which had been sent out at 7:47 a.m. as “An Important Campus Safety Update.”

I’ve been in education for a long time, and I know a “threat” can be anything from a student posting to social media to someone writing a death threat on a bathroom mirror in lipstick to someone phoning in a bomb scare. So, OK, Uncomfortable Student, no problem. Some students might use a threat as cover to take advantage of good weather, but who am I to judge?

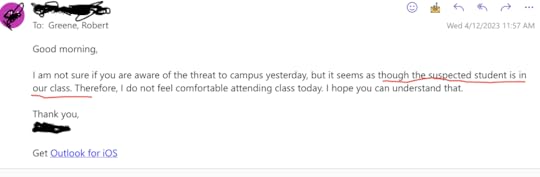

I went back to the top of my email and opened the next student email.

That, friends, is a very different thing. We live in troubled times, and I can’t help coming up with a list of “Most Likely To” in nearly every class. I surveyed my email again, sure I would have received official notice if one of my students had presented the threat, along with some instruction from Public Safety and Admin about what to do and how to deal with it in the classroom.

There was nothing.

I hastened to the dean’s office, hoping to get a sense of what was happening before class started. The Dean wasn’t in the loop, either. She didn’t know much about what happened, nor did she know the student’s name. I offered her my Number One Most Likely To, and she was unable to say it had not been him. She did say that the situation was under control and that it was unlikely that the Problem Child would be allowed back on campus. I asked her if I should cancel class, and she suggested that I do not in order to offer students the feeling that everything was all right.

I went upstairs, and the first person I saw was my Number One Most Likely To. Whew! It’s not every day that you half expect the first student you see to pull a gun and shoot you!

Now I could have made a scene, freaked out and screamed “Don’t shoot me!” but I played it cool, gave him the deadline extension he asked for, and through context clues, eventually sussed out that he was probably not The One. Four students made it to class that day.

I emailed the dean as soon as I could to tell her that I had taken Number One’s name in vain. Later at home, whilst entering grades, I checked my email again and spotted another message from a student, sent the night before and thus far down the announcement-filled Outlook page.

I may not have had any information about this thing, but the students sure did! They had his name and some idea of what he’d done. Threatened our class! Surely, some law-enforcement type or admin would reach out to me and give me some tools to work with, even an answer to an student question I received Wednesday night: “He won’t be back in class, correct?” (Readers, no such reaching out occurred.)

How could I answer the emailed question? Did I know? Was The Problem Child in jail? Was he being watched? Was it impossible for him to drive back to campus and shoot us all? I let my journalism skills and search-fu out, and found nothing in the news or local police records. (Dirty Secret: If a University’s own security and internal judiciary handle an incident, the incident likely will not become public record. This can include sexual assaults, threats, etc.)

I responded to the concerned student,“That is my understanding,” and on Thursday sent an email out to the members of the class:

Was this the right thing to do? Was I violating some handbook protocol? Considering I’d heard nothing from The People in Authority about this, I wasn’t too worried. I didn’t even know Problem Child’s enrollment status. Getting escorted off campus after making threats seems like it would be pretty final.

We had class on Friday, talked a little bit about it, but mostly bent our heads to the work.

So, now, as I write this, it’s Monday. I checked my university email this morning, and the first thing I saw was a message from the Problem Child:

OK, so now this dude who was chased off campus for maybe threatening to end the lives of my students, end my life, and shoot up my classroom, wants me to accept late work, grade that work fairly, and enter those grades like nothing ever happened. (Did it happen? Not according to the Official Reaction. I was a reporter for a long time, and my search-fu is pretty good. Still nothing in my email, nothing in the news.)

Then I spotted this.

To my mind, this message provided very little context. All I know is, a student in one of my classes did something bad enough to get exiled from the campus, possibly threatening my life and the life of my students, and I am being asked by Admin, in its only official communication to me about this, to give him accommodations. (If I don’t will he come shoot me? Is that something I should think about? What happens if I give him an A?)

And, honestly, the admin request merits the least of my outrage over this situation. At every turn, I’ve been kept in the dark, left out of information loops that I need to keep my students and myself safe, make informed choices, and reassure my students that everything was in control.

I’m not happy. Worse, I don’t feel safe, and I don’t feel I have what I need to protect my students. This sucks.

Thanks for reading Twenty-First-Century Blues! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

April 4, 2023

'Man Power'

The obelisk thrust into the sky about a hundred yards ahead. Thirty-feet tall, it stood alone on the rise, a memorial to an ages-old shipwreck, all hands lost. Two flashlight beams flirted over its smooth surface.

D-Too stopped walking and held out his hand. “I need to be way drunker than this.”

The paper bag crunched as Rob handed over the bottle of cheap whiskey he’d carried from the parking lot. They’d already drunk it down to the top of the label. D-Too fumbled the cap open. “Here’s to stupid ideas.” He took a swig and handed the bottle back.

“The Sarge won’t do us wrong.” Rob drank the whisky a half inch lower and screwed the cap back on. “Onward!”

The moonlight went into overdrive as they approached the memorial, reflecting off the gray stone and making the flashlights redundant.

“Took you long enough!” Sgt. Tim boomed. He flicked his flashlight beam into D-Too’s face. “It’s only twelve minutes to midnight.”

“Don’t listen to him. We just got here, too,” said Darren, the thin man beside Tim.

Rob flipped a salute at Tim. “Sarge.” He nodded at Darren. “Darren. Nice night.” He offered up his bottle.

“Let’s get this started,” Tim said. “We miss our window we can’t try again for another year. Circle up.”

The four men stumbled into a rough oval and faced each other.

“There’s no way candles are going to work in this wind,” D-Too said.

“We’ll just use a flashlight,” Tim said. “It won’t matter. Somebody hold one so I can see.”

Tim opened a leather-bound book. Darren spilled his flashlight’s beam onto the yellowing pages.

“This something one of your buddies in Special Forces found, Sarge?” Rob said.

Darren snorted. “Tim was in Intelligence. He read maps and looked at pictures.”

Tim scowled. “The guy who sold it to me is in Special Forces. Now shut up. I need to time this right.” He cleared his throat and read a line from the page.

“Is that Arabic?” Rob said. “What’s it mean?”

“It’s Old Norse,” Tim growled. “And if I stop to translate everything we’ll never get it done in time.” He read the rest of the page carefully. Following instructions scribbled in the margins of the book, the men marched in place and took two steps to the right. They turned in circles and shouted “Heya!” Tim read another page and pricked each man’s thumb with sterile lancets. They mingled their blood on the page of the old book.

“It says here we need to put our dicks together. Unzip.”

“What the hell?” D-Too backed away.

“It says, ‘Bring that which makes you men together’,” Tim said.

Rob fumbled at his fly. “Do they need to, like, cross or just touch?”

D-Too shook his head. “Not doing it.”

Darren sighed. “Just get it over with. Sergeant Rock will never let us hear the end of it.” He unzipped his pants.

The oval distorted as the men tried to get into position. “They need to touch at the stroke of midnight,” Tim said.

“Heh.” Darren chuckled. “He said ‘stroke.’”

Rob struggled to peer over his stomach. “Are they touching?”

“Thrust your hips forward and learn your shoulders back,” Tim said.

The men pushed closer together, eyes on the sky.

“Should I pull my foreskin back?” Rob said.

“Shut up!” D-Too hissed.

The heads of their penises made contact. “Hold it there!” Tim shouted the last line of the spell. Their muscles locked as the power built.

“Something’s happening!” Rob said. “Something’s--!”

###

“How was your weekend?” Angela said.

“Hmm?” Darren stopped playing with the bandages on his fingers.

“The long weekend.” She put her elbows on the cubicle wall between them. “What did you do?”

“Saw some old friends. Guys I’ve known forever. I’ve told you about them.” Darren pointed at the picture on his desk. He, Rob, and Tim had been friends since middle school. The other Darren, D-Too, had come along sophomore year.

“Beer and bad decisions?” she said.

“Something like that. You?”

“Went to Cleveland to see Carl’s parents.”

Darren hid a wince. “How’s that going?”

She made a noncommittal noise. “I understand him better now that I’ve met his mother.”

“I told you.”

She nodded. “I should have listened.”

Darren carefully lined his pen up with his keyboard. “It’s not too late to ditch him.”

“He’s not a bad guy. He’s just --.” She sighed. “He’s soft. You know?”

“Mmm.”

“Are you heading home soon?” she said.

“Just about. Why?”

“My car won’t start. I was hoping you could take a look at it.”

Darren shrugged into his jacket and followed her out to the parking lot. Back when she worked in the cubicle next to his she’d driven an aging Honda Civic. The promotion that moved her to the other side of the building had merited a silver Audi Quattro. It shone impotently in a reserved parking spot near the building’s entrance.

“Did you leave the lights on?” Darren said.

“They’re supposed to turn off automatically.” She handed him the keys.

Darren slid behind the wheel. The starter cranked gamely. He tried to remember what he’d yawned through in shop class so many years before. Cars needed both fire and fuel to run. If the battery had enough charge to crank.... He popped the hood and bit the inside of his cheek hard enough to make it bleed. He lifted the hood.

“Heya,” he said.

“What?” Angela said.

“Nothing.”

Rob showed up first, a cheerful presence inside Darren’s head. Missing us already?

D-Too’s thoughts tasted sour. This is not a good time.

Tim, as ever, took charge. What’s going on?

Darren blinked at the snarl of wires and tubing inside the Audi’s engine compartment.

Angela’s car won’t start.

THE Angela? Rob crowed.

Darren nodded and looked over to where Angela shivered hopefully.

She lit a cigarette. “Can you do anything?”

“Maybe.” Darren found the battery and jiggled the cables attached to it. He could also check the oil, and that was about where his automotive knowledge ended. What do I do?

So, we’re going to use this to impress girlfriends? D-Too said. That’s what we’re going to do with it.

She’s not my girlfriend, Darren said.

D-Too’s derision came through clearly. I didn’t spend five-hundred bucks to impress some chick who put out for you–

Darren’s thoughts turned red. Can you help me or not?

Did she leave the lights on? Rob said.

I don’t know anything about Japanese cars, Tim said.

I think Audis are Swedish, Rob said.

They’re German, Darren said. You all are useless. “Heya.” The other presences in his head faded.

“Did you get it?” Angela said.

Darren closed the hood. “I’ve no idea what to do.”

“Thanks for looking at it.” She said. “I guess I’ll just text Carl for a ride and get a tow.”

###

“Heya!” Rob struck a dramatic pose, arms raised above his head. His fingertip trickled fresh blood.

What’s the problem? Darren said.

Rob pointed. I can’t get that jar open.

Pickles! D-Too said. Now we’re using it for pickles!

Did you try hitting the bottom of the jar with a spoon? Tim said.

I also ran it under cold water. Rob picked the jar up. I tried everything I could think of. I need the Might of the Four.

Alright, Tim said. Grab hold. On the count of three. One. Two. Three!

Their strength combined, and the lid came right off.

###

Heya.

Darren had been deep in REM sleep. One moment he’d been dreaming about riding a vacuum cleaner down the street, the next a thick-set man with onion breath was yelling in his face. What…?

D-Too’s about to kick someone’s ass, Rob said.

D-Too’s fists were clenched, and he was blinking furiously. His lip was bleeding.

“I know plenty of little shits like you!” The thick-set man jabbed his finger into D-Too’s narrow chest. “I work down at the prison. Go ahead. Try me.”

Elaine’s here, Tim said. He’s been looking for her all night. She just slapped him.

“Please come home.” D-Too looked past the yelling man to Elaine. “I’ll sleep on the couch. We can talk in the morning.”

The thick-set man got in D-Too’s face again. “You just try it! Just try it!”

Elaine put her hand on the man’s meaty arm. “He won’t hurt me.”

Watch his right, D, Tim said. You see how he’s moved his left foot ahead?

Deck him! Rob said. You have the strength and speed of the four of us! Put him down!

Get ready to slip under his punch, Tim said. He’s going to loop it. Get inside it, and put your left forearm in his throat.

Get out of here, Darren said. You’re not going to help anything by hitting this guy and getting arrested.

“Just go home!” The stress was clearing away Elaine’s buzz. She was crying and her face was blotchy. “This isn’t about you!”

A well-muscled bald man in a black T-shirt approached them from the left. “Hope we’re not having any trouble here.”

“No trouble.” D-Too’s gut was churning. “I was just leaving.” He turned and pushed through the crowd toward the bar’s entrance.

Good move, Darren said. You can talk it out when-

“Shut the fuck up!” D-Too pulled the heavy front door off its hinges and dropped it on the floor. The noise of the crowd stopped. Elaine covered her mouth with her hand. The big man who said he was a prison guard paled.

What fucking good are any of you?

###

“Heya.”

Catherine Stuart frowned. “Did you say something, Tim?”

Tim shook his head. “Just clearing my throat.”

Hey, Sarge! Rob said.

Tim pulled his sleeve over the scab he’d just picked open. “I’m not sure I understand the question, Mrs.--.”

“Miss.” She smiled. “I’ve seen your file. You spent six years in the Army as a human intelligence collector.”

“Yes, ma’am.”

What’s up? Darren said.

D-Too’s here, but he’s really drunk, Rob said.

Catherine Stuart nodded. “That was some time ago. What have you done to keep your skills current?”

Tim stammered. “I’ve attended several seminars and--.”

“What do you know about computers?”

“Like Facebook and all that?”

She shook her head. “I’m thinking more about coding and algorithms. I have a vendor who says we can save money and prevent more product loss with his computers than you can with your team.”

What do I say? Tim was sweating buckets.

Tell her it’s bullshit, Darren said. Computers are good at a lot of things, but they’ll never be able to match your experience and intuition.

Is that true? Tim said.

Hell if I know.

Tim took a sip of water. “With all due respect, Miss Stuart, that’s wrong. Computers may get there eventually, but they aren’t up to catching the things that my team and I see.”

“The vendor said you’d say that.” Catherine put a folder on the table and opened it up to show two pie charts. “We’ve been running a little experiment. We’ve had his program analyzing our video feeds for the past two months. Want to know what we found?’

Shit! Rob said. Abort! Abort!

“I can see what your charts say,” Tim said. “They did better than we did.”

“Twenty-seven percent better,” she said. “Based on this report I’m recommending that we close your department down.”

Tim felt dizzy. What do I do?

###

D-Too was exhausted, and he couldn’t figure out how to assemble the bike he and Elaine had ordered for their daughter’s birthday. The vodka wasn’t making it easier.

He picked up the cheap adjustable wrench and tightened its jaws on the nut.

“Here we go,” he breathed. “Righty tighty, lefty--.” The wrench slipped, and he skinned his knuckles on the cement floor. “God-damnit!” He flung the wrench at the garage wall.

Once upon a time, Elaine would have come out to see what was wrong. She would have gotten the first-aid kit from the kitchen and sat down with him to puzzle out the gift’s instructions. D-Too could have done it himself if he could just figure out where the English instructions became Spanish and stopped being Japanese, but drunk didn’t help dyslexia. He blotted his bloody knuckles on the hem of his T-shirt.

Rob could have put the thing together without instructions. Tim would have organized them into a crack bicycle-assembling team. Darren’s jokes would have broken the tension. But then they’d know he’d been crying and that he hadn’t been man enough to keep his marriage together.

D-Too kicked the box the bike had arrived in. It wasn’t enough. He dropped to his knees on the cement floor and sobbed.

###

Rob slammed his shoulder into the door again. “Heya! I fucking need you!” The smoke made him cough. “Force of the Four! Heya!” His knuckles were bleeding.

Don’t charge it; kick it! Tim said. Right near the latch!

Rob lifted a size-eleven work boot. The strength of four men drove the door out of its frame and into the room beyond.

Who’s in here? Darren said.

Neighbor lady, Rob said. Two kids.

And a dog, D-Too said. Over near the TV.

The dog, some kind of pit bull mix, was barely visible through the smoke.

People first, Tim said. There!

Rob shouldered open an interior door. A woman was lying on the carpet in lounge pants and a T-shirt. He picked her up with one arm.

What floor are we on? Darren said.

Fourth. Rob coughed. Same as me.

Keep moving, Tim said. Get the kids.

Rob carried the woman back to the living room and into the kitchen.

Why aren’t the alarms going off? D-Too said.

Shitty landlord. Rob punched open the hollow-core door near the fridge. The kids’ room. He slung a child over each shoulder, a pre-teen in pigtails on the right and a kindergarten-aged boy on the left.

Get them out of here! Tim said.

What about the dog? Rob said.

Come back for it! Darren said.

Rob sprinted for the front door of the apartment. As he entered the hallway the sprinklers triggered. He yelled and hammered on doors as he went. The stairwell was clear, but the exit door at the bottom opened only a few inches.

It’s chained, Rob said. Fucking landlord!

Force it, D-Too said.

Rob roared and shoved the door with all of his extra might. The chain burst, and he stumbled into the fresh air. He jogged across the parking lot to lay his neighbor and her children on the grassy median.

Make sure they’re breathing, Tim said.

The woman coughed. “Rob? What?”

Rob took her hands. “I got the kids out, too, Rosara. They’re safe.”

A fire engine and ambulance pulled into the parking lot. Rob flagged down the paramedics and pointed the family out.

Now you can try for the dog, Tim said.

Rob grinned. Supermen to the rescue. He took a step. “Oh, shit.”

What? Tim said.

I can’t--. Rob’s presence faded.

What’s happening? Darren said.

Rob? Tim said. Say something, buddy. Answer me!

###

Darren tucked a $20 in Rob’s breast pocket.

“Drinking money?” Tim said.

Darren nodded. “Something my father used to do. It was either the price of a drink or cab fare depending on who he was talking to.”

D-Too added a five. “Now he has both.”

Tim frowned.

“What?” D-Too said. “I didn’t have time to stop at a machine.”

Tim slid a brand-new pocket knife under Rob’s folded hands. “I told him he needed to lose weight. He’ll be a bitch to carry out.” He rapped his knuckles on the side of the coffin. “It’s quite a box.”

Darren nudged D-Too with his elbow. “Hey, I’m sorry about you and Elaine.”

“It happens. Anything going on with Angela?”

“Nah.”

Tim gripped the edge of the coffin. “Did we do this? Did we kill him?”

Darren sighed. “He would have tried to play hero anyway.”

“We saved those people’s lives,” D-Too said. “He would have said it was worth it.”

“The power’s gone now,” Tim said. “We could go back next year. Try the ritual again.”

“Strength of the Three?” Darren said

“It only works with four,” Tim said.

D-Too wiped his eyes. “How about Jason?”

“That bald guy who played guitar at your wedding?” Darren said.

“Yeah, he’s okay,” D-Too said.

“Does he know anything about cars?” Darren said.

Tim shrugged. “Guess we’ll find out.”

—The End—

News: This post was a bit long (although I hope entertaining), so I will spare you any news. However, if you are in a pre-ordering mood: “Earth Retrograde” is on course for October 2023. Until next time, blue skies. -rob

Thanks for reading Twenty-First-Century Blues! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

March 21, 2023

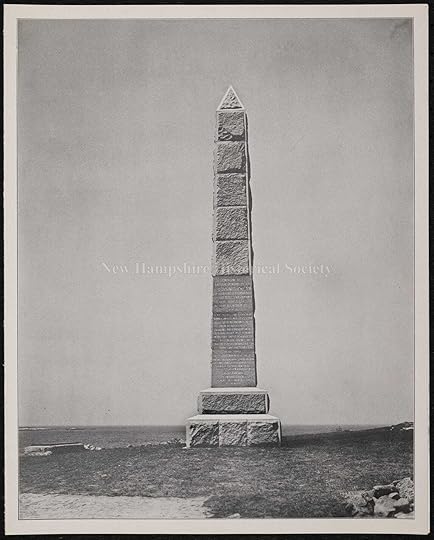

Books for Writers: "Education of a Wandering Man"

When a local used bookstore went out of business a few years ago, I was saddened but I took advantage of the low, low prices to grab … well ... everything.

Among the finds was Education of a Wandering Man, Western writer Louis L’Amour’s memoir. Published by Bantam in 1989 (a year after his death), it’s L’Amour’s account of the life he led while learning to be a writer and, more importantly, the books that taught him about words and story forms.

As an adventure tale, Education of a Wandering Man lacks the drama of Into Thin Air and many other books about leaving the beaten path. L’Amour left home at sixteen to become a hobo, wandering hither and yon in search of work. The jobs (merchant seaman, bare-knuckle boxer, cattle skinner, mine minder) are not especially thrilling, and L’Amour doesn’t go into them in detail. Instead he focuses on the books he read along the way, listing them by title (when he remembers them) and talking about what he learned from them.

“Byron’s Don Juan I read on an Arab jhow sailing north from Aden up the Red Sea to Port Tewfik on the Suez Canal. Boswell’s Life of Samuel Johnson I read while broke and on the beach in San Pedro. In Singapore, I came upon a copy of The Annals and Antiquities of Rajahstan by James Tod.” (Education of a Wandering Man, page two.)

L’Amour committed poems to memory and recited them around hobo campfires to entertain his fellow travelers. In every port and town, the first stop he made was the local library. Eventually, after filling his head with words, he tried to write his own stories. His first published short story appeared in a nudie magazine. Then he broke into the pulps. In the end, L’Amour wrote eighty-nine novels, more than 250 short stories, and sold more than 320 million copies of his work.

There was no rhyme or reason to L’Amour’s reading. If he found a book, he read it. There’s a nice appendix in the back of Education of a Wandering Man where L’Amour lists all the books and plays he read from 1930 to 1935 and 1937. The list starts with Three Philosophical Poets by George Santayana, hops from The War in the Air by H.G. Wells to Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus and ends with The Checkered Years by Mary Boyrton Carody.

L’Amour left formal education early, but praised it for its ability to give people the tools they need for life-long learning. “[Education] should equip a person to live life well, to understand what is happening about him, for to live life well one must live with awareness.” (Education of a Wandering Man, page 5.)\

For a student, the memoir shows that education is something that must be pursued rather than gifted. Broadening the mind is an active process, one that can only happen through search and seeking, reading and reflection. For a writer, L’Amour’s story is a craft lesson in the importance of reading widely and well.

NEWS: I turned in the revisions for Earth Retrograde yesterday. It’s the second and final book in the First Planets duology (the first book is Mercury Rising). If you preorder from my local, Gibsons Bookstore, there’s a good chance you can get a signed copy when it comes out Oct. 24.

I’ll be in Calgary May 15-26 if anyone has ideas of book-related things to do. I’m also planning a cross-country road trip (Boston to Seattle) with my mother in August for my little brother’s wedding, and we’ll be doing book/literary/silly things along the way.

Peace, Rob

Thanks for reading Twenty-First-Century Blues! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

March 7, 2023

Hot Dogs and Cool Cats

It was hard to hear clearly in a pet crematory. The burners roared like jet planes, and the carcasses crackled and hissed as they burned down from meat to ash. The dead weren’t quiet; but they rarely complained.

So, when I heard the noise, I wasn’t sure it was real. It was barely at the threshold of audibility. High-pitched. Intermittent. A cry for help. I opened the trash cans and searched among the bodies. Nothing. There was a garbage bag on the stained concrete floor. I knelt to open it. It was full of puppies.

The crematory at the Oak Veterinary Hospital (not its real name) was my responsibility once, part of a job I walked into during the fall of my sophomore year in high school. I’d worked plenty in the years prior -- mowing lawns, haying, raking blueberries, babysitting stock, pets, and kids -- but real jobs, ones you filed taxes for, were scarce in my home town, population 1,200 with twice as many cows. To get a real job, I had to go into the city.

The vet hospital was in the capital, across the street from a Chinese restaurant, fifteen long miles from home. The hiring process had been intense. The practice owners were a father-son team, I'll call them Drs Paul and Lincoln Sanders, and they both sat in on the grilling.

“How are your grades?” they said. “Why do you want to work here?”

My grades were fine, I said. As for why I came to the Sanders for a job, I blamed James Herriot, the pen name of a writer/vet in northern England. I’d read all of Herriot’s folksy books about his life as a country veterinarian, and watching the show on public television Sunday nights was a family pastime. I was already a certified dairy-cow judge through the 4-H Club, and I loved animals. It stood to reason my skills might lend themselves to the veterinary sciences.

After the interview, Doctor Paul gave me the tour. We hit the ward first, rows of two-level steel cages filled with sick or boarding animals. My role there would be to feed the dogs and cats twice a day, exercise them in shifts, and clean and disinfect the cages. The next stop was the washroom, where I would bathe the ailing and befouled.

The exercise room looked like a prison yard, rows of concrete-block runs topped with chain-link and shut tight with steel gates. The vet showed me the safety pole I could use to move potentially rabid dogs around. I remembered the final scene of Old Yeller, where Travis tearfully guns his faithful hound down, and nodded understanding. The hydrophoby was not on my to-do list.

The last stop on the tour was the crematory. The door was at the end of a dark hallway and led to a long, tunnel of dirty, white-washed cinder block. The roof was made of translucent green fiberglass panels; the light they let in was flu-like.

The corridor sloped to a space about the size of my bedroom back home. On one side was a claw-foot tub on blocks with a grate across the top of it. That’s where the messy carcasses went — autopsies, road kills, and rabies suspects — to drain. On the other side were a row of plastic garbage cans. All the animals that fit went in there. Doctor Paul lifted the lid of the nearest one.

Inside the trash can was a tumble of fur and paws, dogs and cats locked in a stiff embrace they never would have allowed in life. At the very top, a gray-haired terrier snarled, his pale lips and yellow teeth locked in a final grimace of defiance against the reaper. Some intangible part of me whimpered and fled, tail between its legs, and never returned.

Doctor Paul showed me the burner controls. There were two: one for the top burner, one for the bottom. “You’ll want to light it up as soon as you come in,” he said. “Put the smaller animals in first. Once it gets hot, you can put the bigger ones in. Don’t let it smoke.”

If it smoked, we’d get complaints. The Chinese restaurant would call and report the smell of roasting dogs and cats was overpowering the food. If the wind was right, the smell would carry across town to the supermarket, and we’d hear from them, too.

“Check the smokestack,” Doctor Paul said. “If you can see the smoke, they can smell it.” We went back to his office, and the doctor went over the benefits of joining the team. I’d work Saturday, Sunday, and the major holidays (Christmas, Thanksgiving, and Independence Day). On holidays, I’d make triple time. On regular days, I’d make $3.65 an hour. As a bonus, I’d get a fresh turkey for my family’s Thanksgiving dinner.

“How about it?” he said.

“Sounds good.”

After my father dropped me off for my first day, Doctor Paul handed me a brown lab coat to wear, and I went right to the crematory to light the burners. With the oil burners roaring away, I checked the trash cans. The day before had not been a good day to die, apparently, as there were few animals to burn. Most of the stuff in the cans was actual trash: wrappers, boxes, bio waste, and used hypodermic needles. In the bathtub, though, was the headless body of a Saint Bernard who’d been suspected of rabies. The only way to a sure diagnosis was to cut off the animal’s head and send the brain to the state lab. The Saint Bernard was nearly as big as I was and stiff as a board.

I hustled away to the ward to feed the animals, taking careful note of their dietary requirements. Most just needed a scoop or two of food, but some were on special diets. One dog, a cocker spaniel whose owner was on vacation, ate only chicken and rice from a Tupperware container in the fridge.

After the feeding, I went back to the crematory to put the first few animals in. I chose a small beagle-looking thing and two cats to start with. I watched the flames lick their fur for a moment or two then heaved the heavy hatch shut.

I put the first wave of dogs into the exercise yard and cleaned their cages with a pressure hose and disinfectant. The cats moved to clean quarters while I made their cages sparkle, then moved back. By the time the first dogs were back in their cages, the runs re-disinfected, and the second wave barking and scratching at the exercise yard, it was time to check the crematory again.

The beagle compatible and his cat pals were curled and black, their guts thrusting out of their bellies and roasting alongside. It smelled like barbecue. I put in another dog and went back up to clean more cages before lunch.

I was eating my peanut-butter sandwich in the break room when Doctor Paul dropped by. “I’ll give you a hand with the big one down there,” he said.

I nodded.

He waited.

I set my sandwich aside and followed him down to the fire. I took the back end of the big dog, and he took the front. The dog had shit itself and pipes of feces fell around my feet as we shuffled it toward the furnace. The doctor’s end leaked blood but less than I expected. Together, we heaved the carcass through the hatch and dropped it on top of the burning meat.

“He’s not going to fit, is he?” the veterinarian said. The Saint Bernard was too big for the hatch, and all four of his paws were sticking out. “Grab that shovel over there.” I handed him the shovel and watched as he used it to break the dog’s legs. They folded easily after that, and I tucked the big paws in with the rest of the body. “Keep it hot,” Doctor Paul said. “He’ll take the rest of the day to burn down.” I threw the rest of my sandwich away, and punched back in early. I had three cats to bathe and a dog to cover with an oily goop that combated mange, and, after that, I had the second round of feedings and cleanings.

In days to come, I learned the job end to end. The ward was lit with germ-killing ultraviolet lights, so I had a constant low-grade sunburn. The smoke got into my clothes, even though my protective lab coat, which had a tendency to drape into the fire and catch. I learned how to clean the crematory out and went home with ashes in my hair. On Sundays, the hospital was closed to new business, and I could take an hours-long lunch break if I wanted. I usually walked downtown for a pizza and a stack of comic books and sat at the front desk to enjoy both.

In time, I bought myself contact lenses and paid for my driver’s-ed classes and driver’s license. I triumphantly brought home my turkey and shared it with my family for Thanksgiving. I had a real job. Sixteen years old with responsibilities and money in the bank.

The puppies in the bag were dead, of course, and they were young enough that their eyes had never opened. They were mutts, part Rottweiler, maybe, and someone hadn’t wanted them. For $15 a pop, one of the doctors had injected them with a drug cocktail that looked exactly like Windex and put them to sleep. I’d seen it done dozens of times. The doctors had shown me how to hold the dogs’ front legs to best expose the big vein inside their elbows. I’d hold the dogs as the needle went in, and they slipped bonelessly into death. It was quick. Easy. The dogs barely noticed it was happening.

I heard the whimper again and dug deeper in the bag. One of the pups was still alive, snuggled up to his dead brothers and sisters. I pulled him free, the only warm body among the cold and held him to my chest. I already had three dogs at home, two of them rescued from the doctors’ needles.

The foundling squirmed in my arms, trying to get closer to my heart. He was probably hungry. He missed his mother. Likely she was missing him, too, wondering what had happened to the litter she’d spawned. He yawned, flashing his pink tongue and untried teeth.

I carried the pup up the white corridor, through the scarred door, and up the dark hallway. I shouldered open the door to the treatment room where Doctor Franken, a woman new to the practice, was working on an unconscious Labrador with a dislocated shoulder. “You missed one,” I said. I held the puppy up.

“Ohhh,” her mouth twisted in sympathy, “he’s a little fighter.” She rubbed one of the pup’s silky ears between her fingers. “Hold him a minute.”

A few minutes later, I laid the pup back down among his chilly siblings. They’d all be warm enough soon, but it took a while to get the chill out of my bones.

That summer I worked full time and moved up to $3.90 an hour. The morning of my second Christmas in the ward, I’d walked into a full kennel, dozens of dogs and cats barking and scratching for my attention. I couldn’t hear myself think, and the stench was incredible. I fled to the quiet of the unlit crematory. The animals there weren’t asking for much. It’s hard to disappoint the dead. The living, though ...

I gave notice later that day, deciding I wasn’t cut out to be a vet.

Thanks for reading Twenty-First-Century Blues! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.