Devon Trevarrow Flaherty's Blog, page 35

March 3, 2021

Book Review: New Kid

Image from Amazon.com

Image from Amazon.comWell. It’s cute. It’s relevant. It might even be important. It didn’t shine like a beacon, for me. It has a few issues. It also has a few awards.

The “new kid” of the graphic novel New Kid by Jerry Craft is Jordan, and he’s not new to his neighborhood or his house: he has moved schools, which is the kind of thing that happens all the time with urban kids, these days. There are some details based on the New York City school system here that not all of us will understand, but I believe that he has tested into a private school program and is accepted on scholarship? The school is not especially diverse and Jordan is a light-skinned Black student, which divides his parents before he even sets foot in the school. The following graphic novel follows Jordan’s first year in the middle school program at the fancy, mostly rich, high-performing school, focusing on his experience of it racially (and on a handful of the other student’s experiences, from a rich, white kid to some Latino kids, from another Black kid to a “different” little girl). There’s friendship. There’s lots to overcome. There’s plenty of internal and external conflict, though it’s mostly day-to-day and not too dramatic.

I’m torn between feeling like this book is too nuanced and not nuanced enough, which is an impossible situation, sure. But here’s what I mean. On one hand, I feel like it’s so subtle that a middle grades kid who has not experienced what’s going on in it from the perspective intended will run a big risk of not getting it, not understanding what the book is trying to say (which is partly things are not equal, and often awkward as butt—at best—and systemically racist—at worst. Despite a frequent farce of good intentions). On the other hand, some of the things the book has to say are not nuanced enough for me. They appear oversimplified, which is amplified when that oversimplification is repeated, repeatedly. For example, a Black child will learn from this book that people confuse him or her with other Black children because they don’t notice them and don’t care about them. While habitually misidentifying someone is certainly rude, a red flag, and should be addressed, the issue is much more complex, which can be seen when virtually any person of any color is in a minority situation anywhere: suddenly, everyone confuses them with the other person that looks anything like them. In other words, we generalize as a species, sometimes to our own detriment, and that is part of this conversation, not just “They don’t see you. They don’t care.” Also part of this conversation: it feels like they don’t see you and don’t care. Sure.

But beyond some of the things that stood out to me as oversimplified, there was a lot of complication and a lot of representation. New Kid has a lot to say. I can’t decide exactly, though, if in the end it has a positive or negative message. On the surface, it’s positive. Jordan, his closest friends, and his family, are all lovely people who are making the world a better place by being better people. But there also seems to be a more sinister thread running under the surface here, that I just couldn’t shake, emotionally, as I read. Perhaps it’s the anger that crops up in some of the characters, and perhaps that’s not really a bad thing. Feeling the feels is allowed. Understandable. Expected, even. But man does said character get so close to letting his anger eat him up a bit. In a way, I like this tension, but once again I ask myself, will middle grades kids get it?

There are, for sure, issues with the illustrations themselves. They’re just really imperfect. I want to like them, especially since I enjoy most of the characters and am curious about what’s going on in this school, but the drawings… Most of the time, they are just okay, but sometimes they’re distractingly not okay. Why didn’t they get fixed before publication? Unknown. One in particular haunts my dreams: in it, a character’s legs are coming out from their stomach, bent at impossible angles. Why!? My son also noticed problems with some of the illustrations, and brought it up to me. It made him leery of the story from page two.

So, overall I’m not sure what to say. I liked reading the book. It made me think. I found it hard to follow as someone with ADHD, but that’s just me and most graphic novels. My son was distracted by the mistakes in the drawings. I think New Kid has plenty to say into the void, but I’m not sure it says it well. On the other hand, you cozy up to these characters and so go along with them into their struggles, whether or not the issues are oversimplified or nuanced into oblivion. Hm, hm, hm. If you have a middle grades kid who likes graphic novels, add this one to his or her collection, but make sure you have a conversation about it.

Book Review: The Crimes of Grindelwald

Image from Amazon.com

Image from Amazon.comNot a secret: I’m a Harry Potter fan. I read the new stuff as it comes out, including the Fantastic Beasts series, which, if you don’t know, is a five-book series of screen plays set in the Harry Potter world but seventy years before the stories we are familiar with. Which makes Dumbledore really old. I was not real fast on reading number two, The Crimes of Grindelwald, because the series is taking a looooong time to come out and also because it has not had an enthusiastic reception. Especially the movies, which is the point of them.

Somewhere someone has probably wheedled out of J. K. Rowling why she decided to go straight to screenplay with the series instead of writing a more conventional book series. Honestly, I think writing the books would have been way, way better for both the series’ success and also for her readers. Normally, I don’t mind reading plays, though, and there is something about the conciseness, the sparseness, even the appeal to the sense of sight and even sassiness of the medium. Which is to say, I did enjoy reading The Crimes of Grindelwald, just as I enjoyed reading Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them. I don’t know as I have anything new to add to what I already said about the first book, though. It would be best to review this as a series, and yet I can’t because of aforementioned length of time taken to release them.

So to recap from the last review: the series issues are the age of the characters and the setting not being in England, distancing it from the magic of the original Harry Potter in some way. And I am still wondering how long Rowling can support this five-part endeavor. With her resources? Probably for the long haul, but now with the loss of a main actor (Grindelwald), the series continues to take hard knock after hard knock. What I like about the screenplays are Rowling at her best: a very deft creation of interesting characters, dramatic and complex plot, and, obvi, world building with a seemingly inexhaustible depth of fantastic ideas. The book itself is, again, beautiful and—as screenplays are—full of wasted space. But besides word-nerds like me, the moral here is that reading is really not necessary for Fantastic Beasts, nor was it intended to be. Too bad. I continue to be awed at Rowling’s story telling and even her character development in such a limited time, wondering if the second book has gotten a little trite and reused too many old tricks and references, while the rest of the world waits—without bated breath—for numero tres and some sort of CG-makeup-fusion of Johnny Depp’s ghost with some similar actor.

If you want to read the review of Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them, click HERE.

Image from Amazon.com

Image from Amazon.comMOVIES

Because I am such a Potter fan, I own both of the first two movies (Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them and Fantastic Beasts: The Crimes of Grindelwald), which I bought sight unseen when they released. I have now watched them both (this week). They’re certainly not bad, though they have not done very well with critics or audiences. Visually, pretty stunning. Interesting. Full of twists and turns and Potter Easter eggs. They like to leave you hanging, and I think a lot really depends on how they wrap up in the end and how attached we get to the characters over the length of the franchise. What I’m saying is that they are decent to watch, for sure, but the verdict is still out on what they will be as a whole. There’s nothing super-new here, and like I’ve said before, it lacks some of the charm that comes from the English boarding school, but I do want to know more and my eyes have been treated to some CG and fantasy candy.

February 25, 2021

Book Review: Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers

I am a geek, pretty thoroughly. I like much of the geek canon, from LOTR to Star Wars, though I am more of an academic than a gamer. I’m not a gamer at all. But I have a lifelong love of learning which extends into most subjects, though my interest in some of them is specific and random. I enjoy many of the sciences. Among my specific interests is health and nutrition, though I have—sometimes out of necessity—dabbled in psychology and mental health. When a thick, science book on stress-related disease popped up on my book club list, I didn’t think twice about it. But now I’m wondering if—for the sake of others—I should have.

Image from Amazon.com

Image from Amazon.comI suppose science books (or history, for that matter) are not for everyone. Even the books that are written in such a way as to make them have more appeal and to speak to the layman, are just not for everyone. Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers by Robert M. Sapolsky has been popular and celebrated since its first edition publication in 1994. (I believe we’re on the third edition.) But there are two reasons that—two weeks into February—I had to send out an email giving my book club members permission to put the book down or skip to the end. One: it’s still a book on science and it is really dense, especially if this stuff isn’t usual to you or you aren’t interested in it. Two: it’s a stressful read, ironically.

I was reading this book with my Pandemic Book Club precisely because it has been a stressful year. We are seeking emotional health. Zebras was supposed to educate us about how stress is affecting our bodies and then show us some ways to prevent or reverse those effects. Well, on page 308 out of 339, we were still working our way up to the practical application, still finding out, chapter by chapter, how stress is killing us and making us miserable. In fact, the final chapter begins, “By now, if you are not depressed by all the bad news in the preceding chapters, you probably have only been skimming” (p309). Which is what I told my ladies to do, if the book was counterproductively stressing them out.

Sapolsky, you see, is a serious scientist and as such, has to be very thorough and exacting in his presenting of the science. He also happens to be one of the more entertaining and approachable scientists I have ever read, which makes his books popular and—if you go in for that kind of stuff—interesting. If you can take it all cooly, with a grain of salt, then, well, I was LOLing at points. (I don’t want to bring your expectations up too high, but I was certainly, regularly chuckling, anyhow, which is very strange for a health science book.) If you are already stressed out and you tend to get more stressed out about either reading dense books or discovering that your mother’s techniques have doomed your cardiovascular system, then perhaps a stressful time is not the time at all for this book. Like I said, ironically.

In the end, I didn’t breeze through this book, and occasionally I realized I had zoned out during some especially technical passage with more multisyllabic words than a Twinkies ingredients list. Overall, though, I found Sapolsky to be an exemplary science writer. Like I said, funny, interesting, approachable, engaging, full of anecdotes and stories. And wry. Sometimes sarcastic. Balanced, calm, collected. I didn’t feel like he was trying to sell me something. And still, all the while, very careful about what he’s claiming and not allowing others to claim. I was also disappointed by the very small amount of help that Sapolsky suggests at the end and, more importantly for me, how disorganized it is. I would like a list, please, with clear directives or at least suggestions. He gives us little to be going on with, mostly ideas instead of concrete steps. Still. If you have any interest in reading the best of science books, or if you have an interest in stress-related disease, aging (well), psychology/psychiatry, Savannah baboons, or social experiments on rats, then this is a book I would recommend for you. I only wish every subject had a book as well-written as this one for the more-average Joe to read. I’m tempted to explore his other titles, which are:

Stress, The Aging Brain, and the Mechanisms of Neuron DeathThe Trouble with Testosterone (essays)A Primate’s Memoir (memoir)Monkeyluv (essays)Behave: The Biology of Humans at Our Best and WorstAt least the memoir and Behave. All of them have good ratings.

QUOTES:(from the 2nd edition)

“We humans can experience wildly strong emotions (provoking our bodies into an accompanying uproar) linked to mere thoughts” (p6).

“They are generally shortsighted, inefficient, and penny-wise and dollar-foolish, but they are the sorts of costly things your body has to do to respond effectively in an emergency” (p13).

“If you repeatedly turn off the stress response, or if you cannot appropriately turn off the stress response at the end of a stressful event, the stress-response can eventually become nearly as damaging as some stressors themselves” (p16).

“Stress increases your risk of getting diseases that make you sick, or if you have such a disease, stress increases the risk of your defenses being overwhelmed by the disease” (p16).

“…no cell in your body is more than five cells away from a blood vessel…” (p42).

“…some parts of our body, including our heart, do not care in which direction we are knocked out of allostatic balance, but rather simply how much” (p49).

“The central lesson of this chapter is how incompatible it is to plan for the future and simultaneously deal with a current emergency” (p79).

“Sometimes a stressor can be the failure to provide something for an organism, and the absence of touch is seemingly one of the most marked of developmental stressors that we can suffer” (p92).

“In the human, an average pregnancy costs approximately 50,000 calories, and nursing costs about a thousand calories a day; neither is something that should be gone into without a reasonable amount of fat tucked away” (p112).

“Think about it: over the course of [a Kalahari Bushman mother’s] life span, she has perhaps two dozen periods. Contrast that with modern western women, who average perhaps 500 periods over their lifetime” (p115).

“…an artificial rose could trigger an allergic response in a patient” (p126).

“Although evidence is emerging that stress-induced immunosuppression can indeed increase the risk and severity of disease, the connection is probably relatively weak and its importance often exaggerated” (p127).

“The impact of social relationships on life expectancy appears to be at least as large as that of variables such as cigarette smoking, hypertension, obesity, and level of physical activity” (p143).

“As you stress the system—in this case, by making the subjects race against a time limit—scores fall for all ages, but much farther among older people” (p201).

“We humans also deal better with stressors when we have outlets for frustration—punch a wall, take a run, find solace in a hobby. We are even cerebral enough to imagine those outlets and derive some relief” (p215).

“…half of those lacking social support were dead within five years—a rate three times higher than was seen in patients who had a spouse or close friend…” (p217).

“…the more apt description of depression—‘aggression turned inward’” (p251-252)

“…when an organism is rewarded consistently with no control or predictability (that is, no matter what the subject does, it is rewarded), it also has difficulty afterward learning coping responses” (p254).

“…having a genetic propensity toward depression gives you only about a fifty percent change of getting the disease” (p260).

“Repressing the expression of strong emotions appears to exaggerate the intensity of the physiology that goes along with them” (p279).

“If you reduce the hostility component in Type A people through therapy … you reduce the risk for further heart disease” (p279).

“Instead, it says that if you want to change the SES gradient, it’s going to take something a whole lot bigger than rigging up insurance so that everyone can drop in regularly on a friendly small-town doc out of a Normal Rockwell. Poverty, and the poor health of the poor, is about much more than simply not having enough money. As Antonovsky showed, it is also about your psychological interactions with society at large and how readily society registers your existence” (p307).

“Not everyone falls apart miserably with age, not every organ system poops out, not everything is bad news” (p311).

“If you can view cancer and Alzheimer’s disease, the Holocaust and ethnic cleansing, if you can view the inevitable threshold where your own heart will cease to beat, all in the context of a loving plan, that must constitute the greatest source of support imaginable” (p317).

“They emphasize the importance of manipulating feelings of control, predictability, outlets for frustration, social connectedness, the perception of whether things are worsening or improving” (p325).

“It is true that hope, no matter how irrational, can sustain us in the darkest of times. But nothing can break us more effectively than hope given and then taken away capriciously” (p328).

“He warns against trying to assert control over something that does not need correcting or that cannot be corrected—an approach at which Type A’s tend to excel” (p334).

My shorthand list of Steps to Take:

Recognize the signs of the stress response and situations responsible for it.Find a regular, scheduled outlet.Hope, reasonably and protectively. In the worse case scenario, denial is preferable.Seek control, but do not try to control the uncontrollable.Scale by a series of footholds.Seek accurate, predictable information that is neither too soon nor too late, too much or really awful.Find sources of social affiliation and support.February 22, 2021

Book Review: The Well-Centered Home

Image from Amazon.com

Image from Amazon.comWell, I assigned The Well-Centered Home: Simple Steps to Increase Mindfulness, Self-Awareness, and Happiness Where You Live by William Hirsch AIA (I think that has something to do with architecture) to my Pandemic Book Club, as the alternative book for February. (The main book—which I’ll review soon—is about stress and health.) I thought that since we’re stuck in our homes more than normal, it would be a good time to ask ourselves if those homes are comfortable for us or if they could be more comfortable. I was leery about the terms “mindfulness” and even “self-awareness” in the subtitle, but the book came highly recommended by the narrow field of people who had read it.

Turns out the “mindfulness” on the cover was a big tip-off. But it didn’t need to be. What I’m saying is the book is interwoven with comments which I would call pseudo-New Age fluff (being nice), but the meat of the book—the actual architectural insight and practical recommendations—don’t need you to buy into any of that to utilize it. Turns out Hirsch isn’t a religious or psychological expert of any sort (smashing together a random assortment of mostly Eastern ideas that read as hip and relevant nowadays), nor is he a logical wizard or a debate winner. His strengths instead are in his experience with architecture and people (where architecture meets), as well as pretty funny and spot-on (even if not very official) home-personality categories. I found myself not only laughing along to his nailing my and my husband’s peccadillos (from feeling needled by sharp corners to needing a reading chair in a corner), but also having many aha! moments as I looked around my house between reading.

Hirsch recommends some things that can be done right this second: I started opening my blinds all the way (past the midpoint) because he told me it would draw my eye outward much easier and calm me down and darned if it totally didn’t. The book is full of suggestions that run the gamut from do-today for no-money-down, and expensive, long-term ideas that you might want to consider when purchasing your next house. Or maybe I should say should consider, because I really do think there are great ideas here for how to make your house work for you on both a practical and emotional level.

Caveat: besides all the goofy, fluffy stuff, the book isn’t edited all that well, either. There is some needless repetition, awkward sentences, little mistakes that just should have been addressed. I’m reminded that, while Hirsch might be a powerful ally in redecorating, he is not a writer (and, like I said, not a spiritual guru). We don’t need to go near as far as “energy flow.” Personalities—so psychology—and physicality are far enough to make all his suggestions meaningful to you. (Note: I actually would have liked educational asides about how other cultures do architecture, including the spiritual aspect of it, as well as a deeper exploration of how our souls inhabit our space. But where he does that, it’s just not rigorous enough for me and it assumes a lot. For example, when he went through the four ways in which you need to “center” your home, I kept thinking in more rational terminology: for “anchoring,” space or location; for “earth-grounding,” nature; for “solar orienting,” natural light; and for “lunar orienting,” view of the moonrise. Get it? But coming up with new terminology for myself or not, I’m going to respond to blue ceilings and fluffy pillows no matter what we call them.)

I took his test. I’m totally a Galileo (which probably explains my reaction to his writing style and spiritual beliefs), and I’ll be using that as a reference point as I move through my home in the next months, years, and on, to be conscious of what I bring into my house, how I place, it, and how I interact with it. I’ll use the book for color ideas, furniture selection, to put a plant next to my powder room door and two rugs in my family room, because, at heart, what Hirsch has to say here is experienced and makes sense, even if he’s wrapped it all up in a hearty dose of spiritual hodgepodge. It’s brief and dead useful, just not in the best package for me.

February 19, 2021

Book Review: Oliver Twist

Image from Amazon.com

Image from Amazon.comIt is only February, but the first book that put me behind schedule to read 102 books this year was Oliver Twist by Charles Dickens. It’s a classic. I had always intended on reading it. And when Lyddie referenced it over and over in my middle grades Language Arts class, I decided to embrace the moment and stick it on the 2021 reading plan. While there were a couple mammoth novels in January, I stayed on track because they were easy-to-read page turners that kept me up well into the night, turning those pages. Oliver Twist, however, takes more time, more mental energy, and more patience. Therefore, it bled into the reading for the two weeks following its slot (and I have now postponed Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell—a book larger than my head—for my next vaca).

Let’s just get this out of the way, straight away. There is some problematic, negative, racial typecasting in this book. Not only is one of the main villains Jewish, but he is often just called just “the Jew” (though there is a proliferation of nicknames in this book) and there are many disparaging comments made about him that are clearly related to him being Jewish (and some not). There are also a few other racist terms used, and also very importantly, women are problematically, negatively, gender typecast and commented disparagingly about in relation to their being women. Fagin, the Jewish character, is wily and materialistic, brutal and ugly and dirty. Women are unpredictable, stupid, easy, incapable, and best ruled with the rod and controlled very tightly. (They’re also either angels or whores, as the issue goes.) So there’s that. While Oliver Twist could be read as a reflection of the time—which it is—and I wouldn’t want us to forget history or where we have been, I would have a hard time recommending this book as required reading for the reasons I just gave, or to put it at the top of Dicken’s cannon. I don’t know that Dickens was especially racist for his time or place, but Oliver Twist certainly comes across as anti-Semitic and not a little misogynistic.

As for the rest of the book and reading experience: I thought Oliver Twist was okay. As I mentioned, it was a slow read, largely because most of what I read these days is not especially old. When one reads old classics, there is an amount of translation that needs to occur, across the time and space. Dickens uses words that I am unfamiliar with, occasionally (including many low-brow expressions and Victorian English accents in this book), but the real issue is the sensibility of the modern reader versus the Victorian reader. Books were paced slower, back then. They had more patience for description and exposition (though he does remarkably little of that, comparatively). And not regarding pacing, but at the time, drama could be far-fetched and dynamic in a way that we don’t currently expect in realistic fiction. (As the story wore on and plots wove together left and right, it felt like I was watching black and white theater, arms thrown dramatically across brows, characters bursting into rooms with news that immediately brings down the house or incited an insta-mob, etc.)

There’s an element of relief and excitement to reading a book like this, however. The good guy is always going to win. The poor will be avenged. The powerful will be mocked and made fools of. Innocence will be preserved. Etc. This is a story as we expect a story to be told, including the twists and turns and the ludicrous coincidences and the nail-biting suspense. It’s also a very funny book, at least if you are a Victorian Brit. There are chapters at a time that are told with Dickens’ tongue solidly in his cheek. As a modern reader, you could just float right past it and think what a dull boy that Dickens is, but this is very heavy satire: Dickens lays it on thick and as a reader, you can’t take much of what he says at face value. (In a perfect world, this is what he was doing by casting negative Jews and women—socially commenting—but I don’t know about that.) Dickens was very conscious of his writing as social commentary leading to social reform, and Oliver Twist is meant to cast a light on the abduction of orphans into crime rings and the general plight of England’s urban poor. He also spends a lot of energy, here, on ripping Church and State a new one, largely through comedic and grotesque characters. (The reasons Katherine Paterson references it so much in Lyddie is because her main character is a Victorian-era, American child laborer, working in the squalid conditions of an urban factory. She relates to Twist and other characters.) I mean, the whole story is set off when an orphan boy askes his stingy, state benefactors for a second helping! (“Please sir, can I have some more?”) It’s farcical and revealing at the same time.

I guess that’s about all I have to say. I would give the book 3 ½ stars because it’s a solid classic, though not as good as some of Dickens’ other stories. It is satirical, funny, and really dramatic, as long as you tolerate Victorian writing. It’s about characters as much as about a story, and it’s about society as much as it is about characters. Eventually, the reading pays off and you get to gasp many times in the concluding chapters, which leads me to my very last thing to say: man, did it get gory at the end. Surprise! Here’s some dashed out brains, etc. (Not that there’s any lack of brutish behavior up until then: children especially are beaten regularly in Dickens’ Victorian England.) So you might want to know that’s coming, depending on who you have reading this book and, I would suggest that that reader be pretty quick on their toes, mentally and morally.

MOVIES

Am going to watch a couple of the Oliver Twist versions over the next few days. Forgot about that. I’ll update this review next week.

February 15, 2021

Book Review: On Writing

I just lurve this book. Not a line Stephen King would condone, but I’m stickin’ to my guns. (Another phrase he would edit out because it’s cliché.) Then again, this is a blog, where I embrace the conversational and modern tone. On Writing has been on my Favorites list since my first days with this blog, something like a decade ago. When thinking of a dozen titles to list on that page, On Writing was one that I immediately thought of. It has something to do with me being a writer, but my husband—a fan of King’s but not a writer—also likes this book. So, Devon, tell me about this book (if I don’t already know, which is pretty darn likely).

I bought this book from a Borders (oh, Borders!) shortly after it was published in 2000 (and the Borders bookmark still sits nestled at its heart). I can’t really imagine why I bought it, unless it was just that all the writers were talking about it and I was not just an associate editor but adamantly a writer. It was received well and has been essential reading for writers since—it skyrocketed to its place next to The Elements of Style (White and Strunk) and Bird by Bird (Lamott). I avoided Stephen King through my teen years and young twenties after a run-in with a couple of Christopher Pike novels and The Watcher in the Woods. Horror was all I knew of King, and I was assiduously avoiding it. Until my new husband got me to read The Stand. Maybe it was about this time that I bought On Writing? It could have been—I was married in 2001, also the time when I was suddenly free from college texts to read what I wanted. I remember that apartment and reading on the balcony. I also read Bonfire of the Vanities and picked up the L. M. Montgomery I hadn’t given a second glance in years. (Isn’t it interesting that what we read or watch or listen to gives a flavor to memories that doesn’t wash off?)

Subtitled A Memoir of the Craft, On Writing is like nothing else that the prolific King has written. It is a book about writing in three parts. Written well into his career and straddling the headline news of his being nearly killed by launching bodily over the hood of a distracted driver’s van, the book takes its form in three parts: the memoir, beginning in his childhood and kept to the writing-related (titled “C.V.”); the nuts and bolts of writing, advice and craft (titled “Toolbox” and “On Writing”); and the wrap-up including his story where King meets van fender, his survival and recovery (titled “On Living: A Postscript). It’s a well-put-together book. It’s not long (my copy is 284 pages), especially considering it is half-memoir and half-writing lessons. But if King has anything, it’s an ability to write quickly, churn out compelling plots, and self-edit, not to mention a love of the thing. All these are here, in these somewhat brief 284 pages, especially a love of the thing that borders on tenderness.

The stories about his life are engaging, compelling, and they clearly come from a place of experience, hard work, and insider knowledge. You feel pretty cozy with King and somehow still in awe of him. He keeps pulling you in to walk alongside him, but you can’t help but stay star-struck, obnoxiously curious about what life experience makes this man. As a writer, too, you might have to fight a tendency to snobbery and disbelief. King has, after all, pursued the genres of his heart which are not, God bless him, literary fiction or poetry. As for the nuts and bolts part, King is—as ever—completely honest and frank, not afraid to embrace tradition where it works and to buck convention where he finds a bigger truth. The advice lacks ephemerality. He’s the layman of writing teachers, and I, as someone who has been accused many times of taking no BS, respect him tremendously for it. What I’m not saying is that he is dumbed down or lets anyone off the hook. His writing here is smart and funny, and his advice is demanding. (See the quotes below if you want to know more details about what he says before buying a copy. If you’re a writer or a Stephen King fan, you should definitely buy a copy.)

So, after my most recent read (a goal of reading six books on writing this year), I still lurve this book and would still recommend that you give it a read or re-read. Especially if you are in the game, right in the middle, it might be time to freshen up with some no-nonsense advice.

QUOTES

“This is how it was for me, that’s all—a disjointed growth process in which ambition, desire, luck, and a little talent all played a part” (p18).

“There were more doors than one person could ever open in a lifetime, I thought (and still think)” (p28).

“…good story ideas seem to come quite literally from nowhere, sailing at you right out of the empty sky: two previously unrelated ideas come together and make something new under the sun. Your job isn’t to find these ideas but to recognize them when they show up” (p37).

“When you’re still to young to shave, optimism is a perfectly legitimate response to failure” (p40).

“One thing I’ve noticed is that when you’ve had a little success, magazines are a lot less apt to use that phrase, ‘Not for us’” (p41).

“In my character, a kind of wildness and a deep conservativism are wound together like hair in a braid” (p53).

“There was also a work-ethic in the poem that I liked, something that suggested writing poems (or stories, or essays) had as much in common with sweeping the floor as with mythy moments of revelation” (p65).

“This isn’t the way our lives are supposed to be going. Then I’d think Half the world has the same idea” (p70).

“Writing is a lonely job. Having someone who believes in you makes a lot of difference” (p74).

“For me, writing has always been best when it’s intimate” (p76).

“Sometimes you have to go on when you don’t feel like it, and sometimes you’re doing good work when it feels like all you’re managing is to shovel shit from a sitting position” (p78).

“…in the early afternoon I have all the energy of a boa constrictor that’s just swallowed a goat” (p82).

“I bargained, because that’s what addicts do. I was charming, because that’s what addicts are” (p98).

“The idea that creative endeavor and mind-altering substances are entwined is one of the great pop-intellectual myths of our time” (p98).

“Life isn’t a support system for art. It’s the other way around” (p101).

“If you can take it seriously, we can do business” (p107).

“Make yourself a solemn promise right now that you’ll never use ‘emolument’ when you mean ‘tip’” (p117).

“The word is only a representation of the meaning; even at its best, writing almost always falls short of full meaning” (p118).

“…you are capable of remembering the difference between a gerund (verb for used as a noun) and a participle (verb form used as an adjective)” (p119).

“…the reader must always be your main concern; without Constant Reader, you are just a voice quacking in the void” (p124).

“I believe the road to hell is paved with adverbs, and I will shout it from the rooftops” (p125).

“I’m concerned that fear is at the root of most bad writing” (p127).

“…while to write adverbs is human, to write he said or she said is divine” (p128).

“The object of fiction isn’t grammatical correctness but to make the reader welcome and then tell a story…” (p134).

“…you’d do well to remember that we are also talking about magic” (p137).

“But if you don’t want to work your ass off, you have no business trying to write well” (p144).

“If you want to be a writer, you must do two things above all others: read a lot and write a lot. There’s no way around these two things that I’m aware of, no shortcut” (p145).

“Every book you pick up has its own lesson or lessons, and quite often the bad books have more to teach than the good ones” (p145).

“Good writing, on the other hand, teaches the learning writer about style, graceful narration, plot development, the creation of believable characters, and truth-telling” (p146).

“If you intend to write as truthfully as you can, your days as a member of polite society are numbered, anyway” (p148).

“I’d like to suggest that turning off that endlessly quacking box is apt to improve the quality of your life as well as the quality of your writing” (p148).

“…when you find something at which you are talented, you do it (whatever it is) until your fingers bleed or your eyes are ready to fall out of your head” (p150).

“If God gives you something you can do, why in God’s name wouldn’t you do it?” (p152).

“Once I start work on a project, I don’t stop and I don’t slow down unless I absolutely have to. It I don’t write every day, the characters begin to stale off in my mind” (p153).

(This is also where King says that he works on the first draft of a book for no more than three months (one season) and that he writes 10 pages/2000 words every single morning. He also lays out what your writing routine and space should look like.)

“…the job of fiction is to find the truth inside the story’s web of lies, not the commit intellectual dishonesty in the hunt for a buck” (p159).

(This is where King tells us that he is very suspicious of plot and that writers should use intuition and character, not structure, to write a book.)

“The key to good description begins with clear seeing and ends with clear writing, the kind of writing that employs fresh images and simple vocabulary” (p179).

“…one of the cardinal rules of good fiction is never tell us a thing if you can show us, instead…” (p180).

“As with all other aspects of fiction, the key to writing good dialogue is honesty” (p185).

“…writing fiction in America as we enter the twenty-first century is no job for intellectual cowards” (p187).

“…I think that you will find that, if you continue to write fiction, every character you create is partly you” (p191).

“There is absolutely no need to be hidebound and conservative in your work, just as you are under no obligation to write experimental, nonlinear prose…” (p196).

“…you really ought to try to please at least some of the readers some of the time” (p196).

“Sir Arthur Quiller-Couch once said, ‘Murder your darlings,’ and he was right” (p197).

(This is where King tells us to embrace symbolism where it emerges organically and to take a break from your novel, especially after the first draft, which is a fine time to think about theme. Then he shows us his own writing process.)

“What I want most of all is resonance, something that will linger for a little while in Constant Reader’s mind” (p214).

“…all novels are really letters aimed at one person” (p215).

“…beware—if you slow the pace down too much, even the most patient reader is apt to grow restive” (p221).

“The effect of judicious cutting is immediate and often amazing” (p223).

(Then he shares why he’s dubious about writing classes, and some nitty gritty about agents and publication.)

“And if you can do it for joy, you can do it forever” (p249).

“Writing is not life, but I think that sometimes it can be a way back to life” (p249).

“…it’s about enriching the lives of those who will read your work, and enriching your own life, as well. It’s about getting up, getting well, and getting over” (p270).

PS. I wrote an article years ago (on this blog) about being a woman writer as distinct from being a man writer. I lamented the image that King had painted in my head in this very book, of him working a day job and then coming home and writing, with the support of his wife as she threw herself into mothering. I argued that women are wired differently so there needs to be different approaches to the work and devotion required for writing. After this reading, I have forgiven King a little for putting this image there, because I found an allusion to this very thing when King says that his wife, given different circumstances, would have “made it” herself: an acknowledgement, I think, of the differences between us.

February 10, 2021

Book Review: Number the Stars

Image from Amazon.com

Image from Amazon.comThe books we’ve been reading for middle school literature lately (I teach a co-op class) have been so short that the students have actually asked for more reading suggestions. Not all of the students, but still. After Animal Farm and then War Horse, we landed on another super-short novel (which we’re not going to call a novella because it’s middle grades), Number the Stars. By Lois Lowry, the author of The Giver and the Anastasia Krupnik books, Number the Stars is a Newbery Award winner about World War II from the unique perspective of the people of Denmark. Since I loved The Giver, I expected more of the same, but it’s not at all the same. (Also, I had no idea until just now that Lowry also wrote the Anastasia Krupnik books! I would never have pegged one author for these three books/series.)

Number the Stars makes for good, school-sanctioned reading for middle grades students. The writing is clean and the story interesting. From a grown-up perspective, hearing about the War experienced by the Scandinavians from their almost-neutral position and from a population that embraced the Jewish people… it was fascinating. (I liked the five-page afterword with the history as much as the book itself.) The main characters are lovable and even honorable. The insight is nice, especially for middle grades. There’s not much to complain about in this book, though I didn’t find that much to sing from the rooftops, either. While I was reading it, I just couldn’t decide if I liked it. I didn’t not like it. Perhaps the people are a little one-sided, just good without complication. And perhaps this book is best along with a history lesson, at least for kids. I mean, it’s so gentle that it glosses over the Holocaust so that kids could entirely miss the gravity of the situation without some explanation.

AnneMarie lives in Copenhagen, which has been under Nazi occupation for two years. She walks the same roads home from school where the King takes his daily ride on his favorite horse, waving to the people who adore him. But as the war wears on, the word gets out that the Jewish citizens are being rounded up and the Danish grown-ups, already mysterious and secretive, rise up with a plan. Suddenly AnneMarie’s Jewish best friend is pretending to be her sister while Ellen’s parents are missing. AnneMarie wants to know what is going on that the adults aren’t telling her, but she sure doesn’t feel brave. Could she be brave if she had to be?

This is an interesting story and I am glad that Lowry found this largely otherwise-untold piece of history and shared it with middle graders through the eyes of a little Danish girl. The characters and the setting are gentle while the story deals with more serious themes of injustice, fear, and bravery in the face of adversity. I would definitely recommend it for a language arts class from fifth grade through eighth and also as a family audiobook selection. It is excellent to teach both English and history, though perhaps more history. I also would recommend it to adults interested in history and especially in World War II, including lots of tidbits of interest, like how the Danish fisherman used a scientist to dupe the German search dogs. It would take that adult an afternoon to read it.

QUOTES

“If Mr. Rosen knew, he might be frightened. If Mr. Rosen knew, he might be in danger. / So he hadn’t asked. And Peter hadn’t explained” (p91).

Image frim IMDB.com

Image frim IMDB.comMOVIE

There is no movie of Number the Stars. However, it is widely accepted that the Disney movie Miracle at Midnight (1998) is a great movie to screen after reading Number the Stars. It deals with the same piece of history and is also meant as family viewing. I wonder if it wasn’t made because the rights to Number the Stars couldn’t be procured. It is currently available streaming on Disney Plus and I will be watching it with Eamon after he reads the book. I will review it for you then.

February 6, 2021

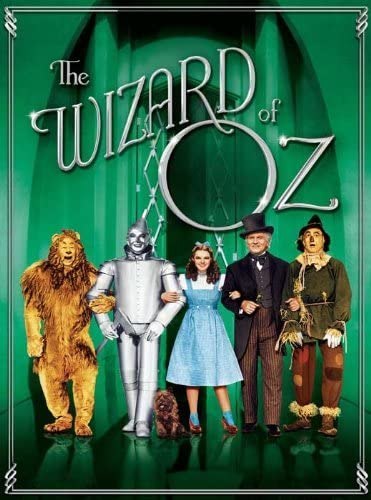

Book Review: The Wonderful Wizard of Oz

This is an old review, which has been sitting at the bottom of my next-up feed for a long time. I don’t really know how it got there or why I kept it there, but it was probably read during a dry period, perhaps when I was sick or on vacation. At any rate, a couple of years ago I actually ordered a copy of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (actually, I think I remember picking it up at a book store) and read it. L. Frank Baum’s book is only the first in a series, though it is often read alone and was of course made famous mostly by the 1939 film that burst into color after the first scenes, to the delight of an audience that had been seeing their fantasy worlds in black and white up until then.

Cover image from Wikipedia.com

Cover image from Wikipedia.comThe series is:

The Wizard of Oz (1900)The Marvelous Land of OzOzma of OzDorothy and the Wizard in OzThe Road to OzThe Emerald City of OzThe Patchwork Girl of OzTik-Tok of OzThe Scarecrow of OzRinkitink in OzThe Lost Princess of OzThe Tin Woodman of OzThe Magic of OzGlinda of OzThe Royal Book of Oz (by a different author) Image from Amazon.com

Image from Amazon.comWith their amazing retro covers and illustrations (if you can find a copy that way), the series is alluring, but I’m pretty sure I’m happy with just the first, classic story and the many adaptations and cultural references. (I read the Gregory Maguire series some time ago, including the book that became the runaway Broadway hit, Wicked.) Perhaps just the first and second one? I’d be curious to hear what someone would say who had read them all. They get decent reviews on Goodreads, all the way through, though it seems most people would have been happy to stop at the first one or two.

I’ll tell you what this book mostly did for me: it made me want to draw and paint, to do art. It inspired me, awoke my creativity, and that’s not half-bad, for a reading experience. That’s what The Wonderful Wizard of Oz is, isn’t it? A trip into the imagination? A slightly psychedelic transportation with a simple story and a little bit outdated writing style? Well, it’s also political, which always makes me want to avoid a book, or at least we all started thinking so in the 60s, which is a time period I find many older books were suddenly found out to be an allegory. Perhaps the issue was with the people of the 60s. At any rate, it is often read as an allegory to either Populism or Jungian psychology, or whatever. It might have had everything to do with the politics of the 1890s (publishing in 1900), but even though Baum was a political activist, it’s not the allegory that really shines here (like in Animal Farm). It’s the story, setting, and characters.

If there is any way you don’t know, The Wizard of Oz is about Dorothy, a turn-of-the-nineteenth-to-twentieth-century teenager who lives with her aunt and uncle on a farm in the middle of absolutely nowhere Kansas. Dorothy has a dog who has a run-in with a neighbor and pretty quickly a tornado comes streaking toward the farm and the real story begins to unfold. Dorothy is knocked out by a shutter trying to save Toto (the dog), and the little house–with only the two of them inside—is transported via tornado to the magical land of Oz, where Dorothy will eventually be joined by the Tin Woodsman, the Scarecrow, and the Lion on her journey back home through villains like the Wicked Witch, conflicted characters like the Wizard, and helpful characters like Glinda. Like I said, the real strong points here are a traditional story with nice variations, a cast of memorable characters, and a setting that makes it fantasy or fairy-tale. We also all know the moral: “There’s no place like home.”

I would recommend it as a classic that is easy to read and one that you could share with your children. I would also be tempted to slate some time afterward to let your imagination run wild and your creativity to flow.

MOVIES

Image from Amazon.com

Image from Amazon.comThe Wizard of Oz (1939) Can there be much to say about this movie? It is so well-known, so classic, so part of our cultural memory. Even my kids, who hate old movies, have seen it and I have seen it so many times I can’t even begin to say how many. But when have I ever sought it out? Maybe just to watch it once with my kids. It sticks pretty close to the book, especially in the moral of the story. Judy Garland is too old to play Dorothy, but she has become the iconic Dorothy with her blue gingham dress, ruby slippers, and braided pigtails, not to mention her warbling of “Somewhere Over the Rainbow.” There are so many mistakes in the movie (as well as so many tales of terrible things that happened while filming), but it remains a cinematic masterpiece. If you haven’t seen it, it’s still entertaining to watch, today, though you’ll definitely feel the age of it.

Image from Amazon.com

Image from Amazon.comOz the Great and Powerful (2013) Told from the point of view of Oz the magician (and eventually “Wizard”—as in there is no Dorothy in this movie), this movie was a much anticipated prequel and not much celebrated. It has okay ratings on Rotten Tomatoes and IMDB, so I wouldn’t completely write it off. If you’ve just read the book, it would be fun to watch, though, as I said, it doesn’t follow the story in the book (though it may have some basis in some of the other books? Somehow I doubt that with its modern feel). It’s full of big name actors, CG effects, and vivid, imaginative scenery and costumes, but it just didn’t come alive for people. I don’t remember it super well, but most complaints are of the flimsy story and some bad acting or at least casting. There are those who love it, too.

(I found my old review: “In some senses, this movie was just what it should be: full of saturated color, crazy characters, and good versus evil with some in-between. I didn’t find James Franco’s acting as horrifying as some complained of (I thought the China Girl was more mediocre). What I did find distracting was 1) the slightly outdated CG and 2) the pacing. There were scenes that seemed so slow to me. I even found both Oz’s and Glinda’s talking to be slow. The promise of the beginning credits just didn’t flower into a wonderful movie.”)

Note: I will eventually be re-reading The Wicked Years series by Gregory Maguire to review for you. It was many years ago, but I remember liking them despite finding fault with them literarily.

*HERE is a review for Marvel’s The Wonderful Wizard of Oz graphic novel.

February 3, 2021

Media in Review: January 2021

THE GOOD PLACE (series, 2016-2020)

Image from IMDB.com

Image from IMDB.comWhen I mentioned to some friends that I was watching this show, I was surprised when they said, “Ehn. It was good, and then it wasn’t. You’ll see.” I was so enjoying it. Quirky. Funny. Full of interesting characters. And just an interesting (if slightly heretical) idea: a young woman dies and is taken to “The Good Place,” one of many heaven-like neighborhoods that has been especially orchestrated to fit the few dozen reeeeally good people who made it there, including each one of their soul mates. But it takes only minutes for Eleanor (Kristen Bell) to realize she doesn’t belong there and only a day to notice that her presence is causing mayhem. Can she—with the help of her supposed soul mate—become a better person and fit in to heaven enough to go undetected and avoid the flames of the Bad Place? Then the first season ends with a twist and the second season becomes a remake of Groundhog’s Day. I am not a fan of Groundhog’s Day and I was not a fan of the pace of that second season. I petered off. I have not yet gone back, though I may, because I would like a return of the innovative show of the first season. We’ll see what happens. The reviews are actually amazing and I should probably finish the four seasons, sometime soon.

THE TRUMAN SHOW (1998)

For the new year, I decided to buy myself a DVD player for my bedroom and watch the DVDs in my collection, beginning with A. Before the player arrived, my kids pulled The Truman Show from the collection and we watched that together, in the family room. We had all watched it before. It was a good movie before and it’s still a good movie, one that encourages discussion during and afterward and is also fun to watch. I mean, I know what’s going to happen at this point, but a new viewer would be kept on the edge of their seat, making all sorts of discoveries. The idea is even good: Truman (Jim Carrey in one of his more serious roles) is born into a reality TV show which the whole world has watched for decades. But can he be kept in the dark forever? And what is the moral cost? And to make things more interesting, Truman has some old things that haunt him—the death of his father and an old flame—that we know more about than he does. It’s a nail-biter. It’s quirky and stimulating and well-put-together.

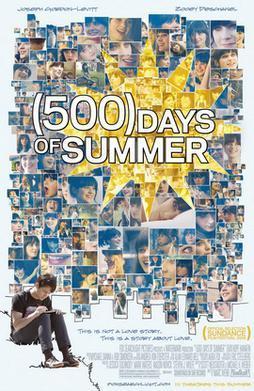

(500) DAYS OF SUMMER (2009)

Image from Wikipedia.org

Image from Wikipedia.orgI bought myself a DVD player after Christmas, so that I can watch my collected movies in my bedroom, if I so want to. In celebration, I am going to move through what I already own. They sit on the shelf alphabetically, so I began with 500 Days of Summer (numbers come before alphabet) and immediately noticed something that I knew was going to be a pattern: I appreciate the quirky, the unique and artsy. I really enjoy it when a director (or writer) veers off the beaten path just enough to capture my attention and imagination. 500 Days of Summer is one of these movies, for me. Sure, it’s just a romance, and sure, it is supposed to be a little turned on its head based of its outcome/plot (I’ll try not to spoil it, though the dedication at the beginning will give you a hint), but it’s something else that I am referring to. It’s the little things. The way two scenes are sometimes spliced together, the way time jumps back and forth with a ticker of 500 days, the way scenes are replaying and re-cut to show you something you missed before. There are quirks I find annoying, actually, like the kid sister/sage thing. She’s like fourteen, and I’m not buying it. Also, the ending, if you’re not on your toes, can be disconcerting the first time you watch it. But overall it’s a movie that I love and will watch again, largely because of the film-making.

SPIES IN DISGUISE (2019)

Image from Amazon.com

Image from Amazon.comHonestly, I didn’t want to watch an animated movie about a spy who turns into a pigeon. I don’t usually like spy movies and I don’t like pigeons. However, this was the one title we could all agree to in a family night perusal of our streaming services, so on it went while we munched our pizza, pasta, and salad. It was quite a bit better than I feared. It was really okay. It’s reassuringly predictable, visually pleasing, and fine for family viewing. And there’s not much more I have to say about that. Fine family movie for a one-time watch.

ABOUT A BOY (2002)

Another anti-romance with quirk factor and artistic direction. See some themes emerging? This one is less blatantly artistic that 500 Days of Summer, but still. And it’s British, which is yet another pattern you will see emerging in my movie collection (and book and music collection, etc.). It’s funny—sometimes I look at the DVD spines on the shelf and I recall the synopsis and I think, ehn. But soon after popping them in, I remember that my liking these movies is not frequently about the context as much as the execution. Again, it’s the little things. And for this one, I was laughing out loud, partly because I am too old to freak out emotionally about the trials and travails of high school, though this kid has some very serious trials. I mean, the teen is so subtle, it’s comic gold. But it’s also very sweet and meaningful and sad and all that. More than just “about a boy,” this movie is about—as stated in Hugh Grant’s introductory monologue—men are islands, or perhaps maybe not islands. It’s about how the most unlikely of characters insinuates himself into Grant’s character’s selfish, kind of boring-but-also-pleasant life and underscores what his sister’s been telling him for years: he is missing out, he is broken. And it’s for a reason he would scarce believe: someone needs him. All the British stuff that happens in between—vegetarians, new trainers, single parent support meetings, rap music, and terrible singing—rise up to support this perhaps tired concept and make it a special movie that shines in the gloom.

ABOUT SCHMIDT (2002)

Image from Amazon.com

Image from Amazon.comFor years after being exposed to this movie, Kevin and I would sometimes used the phrase, “Dear Ndugu,” to refer to it. It’s one of many movies in my collection that has disappeared from the public eye but that has some things to recommend it, to make it special. Here, instead of quirk, we have a slow and painful satire about the mediocre. And really, it is slow and painful with a glaring spotlight on the mediocre. Still, there a lot of special touches that make this movie stand out from the rest. The acting. The details in both writing and cinematography (for such mundane topics and vistas, especially). You’re watching a train wreck, but you can’t look away, and Jack Nicholson’s correspondence with his sponsor child just throws a rope to lasso the whole mess together. More serious (even depressing) than most of my favorite picks, it’s a movie that will always have a place on my shelf.

ADVENTURES IN BABYSITTING (1987)

Image from Amazon.com

Image from Amazon.comSo, the next movie in the ABC’s was Adventures in Babysitting. I don’t think this is actually my movie. Did Kevin buy it from a bargain bin? Did someone gift it to us? I actually had never seen it, so I put it in the player and watched. Not gonna’ be a favorite, but I can see why it’s an 80s classic. It has all the elements that were popular at the time, so if you watched it then, it probably has a place in your heart (like me and The Goonies or The Breakfast Club). In fact, if you are in to those types of movies (with the hair and the clothes and the music and the high school romance and the obnoxious character and the cute kids and, in this case, babysitting and the city and organized crime), then this must go on your to-watch list. Standard done exactly as it should be.

Image from IMDB.com

Image from IMDB.comTHE BABY-SITTERES CLUB (Netflix series, 2020)

My family was not going to join me for most of my viewing-through-my-collection. Also, our family movie nights have been much abbreviated lately by homework. Kevin made the decision that we would start a TV series, and I was pleased as punch when the kids agreed to The Babysitters Club, on trial. I am aware that The Babysitters Club is not high art. I looooooved the series as a kid. It was my first reading love, really, and I devoured the series as each new book came out (up to maybe 40 books at the time). I have enjoyed the Raina Telgemeier graphic novels of the first three books, and now there is a series! Three weeks (and three to five episodes in) and I am giddy whenever we turn it on. It’s so basic, and while I am just so happy to be back in Stoneybrook surrounded by my familiar friends (though it is updated to be current times), I have been surprised that my family is also enjoying it. I don’t know what’s exactly to love about this series, but it is good, clean fun.

ALMOST FAMOUS (2000)

Image from Amazon.com

Image from Amazon.comStill on the A’s. I haven’t watched Almost Famous is a very long time. I couldn’t even remember what I loved so much about it that I own a copy, though I could remember liking it. And watching it again, it’s sort of a borderline case, for me. For one, it doesn’t exactly stand out from the pack of movies, except that it is very well executed. I mean, it’s based on Cameron Crowe’s actual story, but we’ve seen this scene before: a kid gets a job writing for a big rock magazine and goes on tour and there’s all sorts of depravity and backstage conflict and back home, a family that highly disapproves of the scene. Well, maybe we’ve seen it before because Almost Famous started the surge of movies like this (many of them biopics based on real musicians and bands)? Recently, I enjoyed How To Build a Girl and loved Rocketman, more of the back-scenes of drugs, sex, and rock’n’roll and how the initiate can survive and be true to themselves amidst the pomp and flash. But both those movies had things to distinguish them from the pack (though magic realism in movies is increasingly done and—dare I say it?—might become overdone soon). Almost Famous is more of just a well-made classic, full of characters and moments that we’ll remember for a long time. (It is well acted for a sort-of light-hearted movie, except for (hate to say it) Jason Lee.) It has great reviews everywhere one looks, so if you haven’t seen it, you should.

AMELIE (2001)

Image from IMDB.com

Image from IMDB.comIf you don’t do subtitles, move on. If you don’t understand French culture to some extent, move on. But if you’ll watch subtitles and even mildly tolerate French culture (and are old and amenable enough to handle some rather gratuitous and yet abbreviated sex stuff), then this is a great movie and you should see it. It made a splash in 2001, when I first saw it and decided it was a favorite. Audrey Tatou exploded into the American imagination, so adorable and feisty and quirky and broken and not broken. And this film? While having some of the flavor of classic French cinema, it was also toned down into a world-wide universality. But it piled on the little things: Amelie addressing the camera amidst a saturated background and a strange cast of characters, Amelie alone in her apartment and yet surrounded by the other tenants, her co-workers, her distant father. We start the romance with her birth and, without having to become fantasy, the movie is full of magic, and observation after life-observation. We can almost feel, taste, and smell this movie as it unfolds: it sits so close on our eye that it almost chaffs. But we’re always cheering for Amelie, even if she isn’t perfect. And, when we’re done, we want to go out and embrace life the way she does, walk through her neighborhood, and get our hair cut like hers.

AMERICAN MOVIE (1999)

Image from Amazon.com

Image from Amazon.comI pretty much forgot this movie existed. To be fair, it’s probably actually my husband’s movie. A 1999 documentary about a guy who spends three years finishing up his (underfunded, backyard) independent horror film, this is the true-life version of an About Schmidt and once again we feel the pain of mediocrity. It also feels a bit like Tonya, except while Tonya was able to crash out of her town onto the world stage, this guy was having a much harder time becoming the film-maker he wanted to be. It could have been lack of opportunities. It could have been a deficit in talent and motivation. Likely it was both. And just like the other movies I mentioned, we can’t look away. I was riveted to the screen and felt a little guilty for it. I mean, I know these people, I know this guy, and we’re just staring at the soft underbelly of their lives, marveling, poking, and of course also judging. It’s a great documentary. I don’t know how they found this guy or what possessed them to follow him around for a couple years, but it’s done well, reviewed highly, and, if the subject matter interests you in the least, it’s one to see.

Image from Wikipedia.org

Image from Wikipedia.orgAMADEUS (1984)

For my final movie of the month and, coincidentally, the last A in my collection, I watched an old favorite: Amadeus. Here is my one complaint: this movie was a little ahead of its time, and yet there was a time when every serious movie was three hours. This has made it difficult for me to go back and watch some of the films from this period, even if they are good: Braveheart, Schindler’s List, Titanic, etc. It’s just that the pacing tends to be slower than we’re used to, during a time in cinema when they were stretching things out without applying all the bells and whistles that we use today to get binge-watchers to invest days of their time at a time. That said, Amadeus is still one of my favorite movies. Based on the lives of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and Antonio Salieri (his contemporary)—including plenty of speculation and guessing—the story is told from Salieri’s perspective as, committed to an insane asylum after attempting suicide, he claims during a very impenitent confession to have killed Mozart. We then follow the two men’s lives from childhood through Mozart’s early death, in a romp of amazing music, flamboyance of theater, over-the-top outfits, amazing performances, and impeccable tension. It’s funny (but not overtly comedic) and disturbing. Everyone is impossibly flawed. And we get the message: not only is Salieri as insane as Mozart was, but how could such a lousy person be the medium for such pristine talent? A great movie.

January 28, 2021

Book Review: We Were Liars

Okay, whatever you do, do not read this book and then watch the book trailer. It will make you so very sad that since its crazy popularity in 2014 and its release to be adapted, there has not been a movie made. The book trailer is so good. It doesn’t help that I love that song (“I Found” by Amber Run).

Image from Amazon.com

Image from Amazon.comSo, I set out this year to read 102 books on a very tight, strict schedule. I thought I would try that approach, and reading has been a comfort to me during the pandemic. A week into the year, my 16-year-old daughter walked into my bedroom and handed me the book she had just read, We Were Liars. “I think you’ll like this.” Well, I’m not going to turn that down. So I stuck it on my bedside table with my current reads and a week later I discovered I was shockingly two days ahead of schedule (thanks to staying up all night reading The City of Brass). I was hoping I could finish We Were Liars by E. Lockhart in a couple days. Hah! That was easy peasy. It’s a page-turner.

The hype about this book is the “twist.” Readers are warned not to give it away to others. I didn’t know much about the book, so I just started reading, my daughter having obeyed the directive on the book cover and in the marketing material. “Don’t talk about it.” Now here’s the bummer: I knew exactly what was going on in this book from almost the beginning of the book. Here is the thing: I am a writer and a reader, and–even more importantly–I am a born storyteller. It is really difficult to pull one over on me in a book or a movie and I get really excited when a book or movie manages to. It is evident that this book would be best if you were taken in and kept guessing. Unfortunately for me, it didn’t work. Fortunately for you, it probably will, as a vast majority of people say they were thrillingly surprised at the conclusion. Great. Love it. Bummer for me. (Of course, a book like this never will do as well on a second reading, really, but that’s okay. It’s a great experience for most readers.)

Twist aside, I was taken in by this YA book right from the first page. Told in beautiful language that at times is actual poetry (and sometimes is even fairy tale), it didn’t really sound like YA (though it felt like YA due to subject matter and voice). The book is fast-paced, moving through four distinct sections that all tie seamlessly together. The characters are great and the story is super interesting. As in a lot of YA, the characters might have been presented as a little too sophisticated for their age, but I totally wanted to be their friend. In fact, all the characters are well fleshed out, and you can’t totally hate anyone (though you can come pretty close), as everyone has their foibles. The one thing that my daughter did tell me about was something she thought I would enjoy: occasionally the first-person narrator, Cady, is narrating all normal and then says something completely crazy ridiculous and you realize she has just used imagination and hyperbole to explode her emotional or even physical experience all over you. For example, Cady gets migraines, but instead of saying “I had a migraine. It hurt a lot,” the reader is suddenly watching a woman over Cady’s bed hacking into her forehead with an axe. It’s an excellent literary device and I did love it.

Considered a mystery, We Were Liars is presented from the point of view of Cadence Eastman, the eldest grandchild of the wealthy and powerful Sinclair family. Every summer the three daughters convene on their parents’ private island, where the father has built each of them a house. Over the years, the families have grown and changed and the eldest three grandchildren along with a regular guest have melded into a tightknit group who call themselves “the liars.” (I have read that the real explanation for this name was cut along with a fifth section. It does seem pretty unexplained.) After summer 15, however, Cady is alone, at home, with amnesia and crippling migraines and she can’t remember why or what happened to the rest of summer 15. What did happen and how can she get those memories back? Why are her cousins silent? Why was she swimming alone, half-dressed, and now have head trauma? There is romance, there is intrigue, there is thought-provoking conversation, social issues, friendship, family. It’s dreamlike and chilling and exciting.

Here and there, a detail misses. I find this the biggest problem in the believably of the ending. It’s not the entire ending that has an issue—the twist is pretty good, people love it—but a specific part of the ending. It’s just goofy stupid and I really wish it had been addressed in edits. I’m not the only one who feels this way, and just that one problem was big enough that it really put a fly in my ointment. Also, I think people try to read too far into this book. I disagree with people that Cady is an “unreliable narrator.” I think that she is a reliable narrator with amnesia who is discovering reality and herself, but I don’t think that makes her unreliable and I believe we know the truth by the end. There’s enough brokenness in the characters and the situations without having to dig any further and come up with “theories” about the story. It has layers, already. It has things to talk about. It’s a beautiful mess.

So yeah, I unabashedly liked it. One of the best YA books I’ve read and so modern and relevant, to boot.