Brandon Stanton's Blog, page 39

February 8, 2021

(2/8) “There was a lot of therapy for both of us. A lot of...

(2/8) “There was a lot of therapy for both of us. A lot of father son time. But no matter how far we came, I was always on defense. Always afraid of relapsing. One wrong step, and I knew I’d lose Red for good. I was starting to get depressed working as a line cook. My life had just been so shitty, and I was anxious to do something positive. To make a difference in some way. It was my therapist who first suggested a career in recovery. She told me I’d be able to help other addicts with my experience. She pointed me toward a training program, and she gave me the little boost of confidence I needed. I ended up getting hired at a local drop-in center. It was this big, old mansion in South Minneapolis. And they gave me a job in the kitchen, which was super rad. Because I got to make these giant meals for homeless people. There was a small rec room in the basement where clients would play board games. I spent a lot of my extra time down there, just talking to people about recovery. Telling them it was real. And possible. Sometimes I’d share my own story with them so they’d feel less alone. But mostly we’d just hang out and play card games. We were playing a game called ‘Skip-Bo’ when I first met Lizzie. It was her first day interning at the facility. And she must have thought I was a client, because she sat down at our table and introduced herself. I was trembling when I shook her hand. My confidence wasn’t high at the time. I’d been on a few dates, but not really. Women tended to lose interest as soon as they learned my history. And Lizzie was just stunning. College educated. A perfect ten. We saw each other quite a bit over the next few weeks. We worked in the same area a lot. We’d have some small conversations. But I was too scared to make a move. Then one day I asked her to help me carry books to the library. It was so stupid, man. There were only like four books. But it gave us ten minutes together. And when we finished we sat down outside and shared a cigarette. There was this moment where she reached over and put her hand on my leg. It was there for a minute, man. Not long enough to be awkward. But definitely long enough to say: ‘I’m interested.’”

(1/8) “His mother was Red Lake Nation American Indian. So we...

(1/8) “His mother was Red Lake Nation American Indian. So we named him Redick, because we wanted to call him ‘Red.’ He was born the month I started doing heroin. And by the time he was five years old, we were living in a flop house with some serious gangsters. We’d sold all the furniture. There was no heat, no electricity. But Red must have thought everyone lived that way, because he never questioned it. He never asked why we weren’t eating. Or why I disappeared for days at a time. The moment I walked in the door he’d just jump into my arms. Like any five-year old would. So the guilt is heavy, man. It’s thick. He ended up being taken away by the county. It was a rightful case. His mother went to prison, and I was told to get sober or I’d lose my son for good. That night I wandered into a medical detox facility. It was winter in Minnesota, so they thought I was homeless and looking for a warm bed. And they were right about the homeless part. But I was serious about getting sober. I stayed for the next hundred days. Then did six months outpatient. When I finally found a job working as a line cook, the court let Red come live with me again. The two of us moved into my mother’s spare bedroom with everything we owned. I wasn’t ready to be a single father. The parenting classes helped a little, but I had no idea what I was doing. And Red was having a tough time. We hadn’t gotten him ready for school, so the poor guy never had a chance. He’d bang on his desk. He’d get up and leave the class. One day I had to bring a Child Protection officer with me to visit the principal’s office. It was so embarrassing, man. Everyone in that room knew it was my fault. Later that night Red and I were sitting together on the edge of the bed, in our little spare bedroom. And he tried to apologize to me. He told me he was sorry for being bad. ‘None of this is your fault,’ I told him. And I tried to explain everything. My trauma. My addiction. My choices. All the stuff that had led us to this point. And I think maybe I broke down a little bit. Because Red put his arm around me and pulled me close. This little, innocent 40 lb guy, ended up giving me the support I was trying to give him.”

February 4, 2021

“I came in with a plan. I read all the parenting books. I bought...

“I came in with a plan. I read all the parenting books. I bought all the right products. And everything seemed to be going perfectly. The ultrasounds were normal. Audrey arrived exactly on her due date, punctual, like me. But when we went for her two-month checkup, the doctor brought a coworker into the room. They had all these charts, and they explained that Audrey had a genetic mutation. It was clear that something solemn was happening, but they never said ‘disabled.’ Or ‘special needs.’ They used the word ‘delayed,’ so I assumed she’d be able to catch up. I knew she was progressing slowly. But the full weight of it didn’t hit me until we had her evaluated for kindergarten. They used the word ‘severe.’ And that’s never a word you want to hear associated with your child. They gave us a tour of the ‘special needs’ classroom, and I didn’t handle it well. To me ‘special needs’ meant the world moved on without you. The future seemed so bleak. And I kept thinking: ‘I’m not a good enough person for this. I’m not what my daughter needs.’ We’ve come a long way since then. Audrey is eight years old now. And the work can be back breaking, because she needs so much of me. But she’s so happy and playful. She goes bowling and swimming. She has dance parties. I’d been so worried about her making friends, but she has more friends than me. So Audrey is fine. I thought I’d need to teach her so much, but she’s the one who had to teach me. I’m the one who was digging so hard, needing life to look a certain way. It was always so black-or-white. Either my life is good, or it’s not. I couldn’t accept my situation. I couldn’t accept my daughter. And I couldn’t accept myself. I’m still not where I need to be. I can still get resentful over the life I believed I was promised. But I’m 70 percent there. And when you’re coming from zero, that’s pretty good. But the goal is 100 percent. I only have one life, so my goal is to just be with her. To look at her without any of these other thoughts in the back of my head. And to accept that my dream for Audrey is not ‘The Dream’ for Audrey. The only dream for Audrey should be that she’s fulfilled. And in this moment, that’s exactly what she is.”

January 29, 2021

(11/11) “There was once a little girl who was brought up to be a...

(11/11) “There was once a little girl who was brought up to be a dependent. But one day she started acting like she was in charge of her own life. And it raised doubts and fears in everyone around her. In the people of her town. In her family. And it also raised doubts inside of her. Those doubts are still there. Even with how far I’ve come, the fear is always with me. The fear of falling backwards, all the way back to my home. Sometimes I feel like there is so far to go. Until I’m finally safe. Until I’m free forever. But I’ve come so far. I know that. I’ve been able to impact my family back in Pakistan. Financially, of course. But more importantly I’ve provided an example. Now even the shyest of my female cousins are speaking to me about their dreams. One of my younger sisters is working as a fitness coach. And the other has built her own women’s health company. She’s selling sanitary pads, and is having a huge impact back in Pakistan. But the biggest transformation has been in my mother. She’s been promoted to headmistress of her school, and she’s thinking deeply about child development. She’s opening up computer labs. She’s pushing her female students to learn technology. To create their own space. And to be financially strong. She’s telling them all the things that I needed to hear as a little girl. The road was so lonely for me, and maybe I still carry some unconscious resentment. But my mother has apologized for not supporting me more. And consciously I have forgiven her. Recently she’s become vocal about her own story. She also came from a large family. She was the eldest daughter, and like me she was pressured to get married. She was just a young girl. And she was scared. So she grew into a mother who pushed that fear onto her daughters. And I understand that. She was a product of her time. The internet didn’t exist. There was no window to another world. No example to follow. No woman to show the way. I asked her recently: ‘Did you have dreams when you were young?’ And she said: ‘Don’t go there.’ But I pushed her. I said: ‘Go on, tell me.’ She was quiet for a minute. Then she said: ‘There were so many. But I’ve always wanted to be a pilot.’”

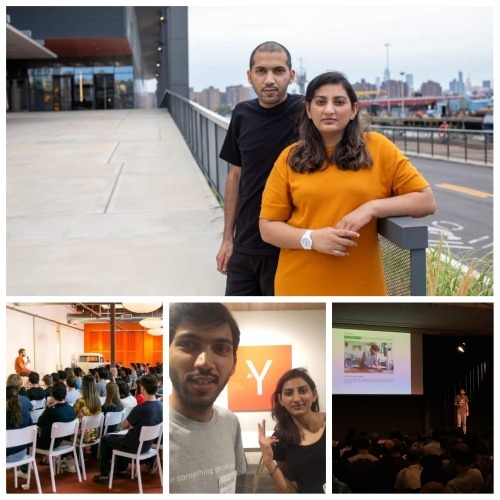

A Note From Brandon:I have received no compensation for this story nor do I have any stake in Atoms. I’ve paid full price for all my shoes. And beyond this, I insisted on paying full price when I ordered ten pairs as Christmas presents. These were the best received gifts I’ve ever given. My agent went on to buy an additional seven pairs in every color. And he also ordered two more pairs last night in case this story cleared out their warehouse. I chose to share Sidra and Waqas’s story because it’s inspiring, but also because they are two of the most humble and kind people I know. I care for them greatly and very much would like to see them succeed in their dreams. It is in this spirit that I’d like to announce that Atoms is giving $30 off their shoes to all the readers of this story. You can redeem the coupon by clicking here: https://bit.ly/3j43ccc

(10/11) “It took several months to manufacture the collection....

(10/11) “It took several months to manufacture the collection. But we kept sharing our story on social media. And we kept sending out samples. By the time we were ready to launch, 45,000 people had signed up for our mailing list. On the first day of sales our website crashed. And by the end of six months we’d sold 12,000 pairs of shoes. Our company expanded to twenty-five employees. But despite our success, our insecurities still worked against us. We were still immigrants. And brown. We had spent so many of our formative years learning from Americans: listening to their interviews, reading their articles. But now we were running our own company. We had to stick with our own instincts, even when Americans disagreed with us. It hasn’t always been an easy road. It seemed that whenever we took a big step forward, a disaster would happen. We went through a round of layoffs. And the beginning of the pandemic was a dark time for us. Our money was nearly gone, and our investors would not commit another penny. That’s when I made the decision to produce a collection of masks. Everyone advised me against it. They told me to stick to shoes. But I developed the samples in secret, built the supply chain, and launched the collection myself. One year later we’ve sold 500,000 of them, and donated 500,000 more. Our shoe business has continued to grow, and once again investors are calling on the phone. That’s how it’s always been. Over the past ten years, every time it’s seemed like we’ve reached the end, something wonderful happens. Last weekend Waqas and I took our first break in a long time. We took a train to the Hudson Valley. And for the first time ever, we had no plan. We gave ourselves a moment. A moment to celebrate how far we’d come. We visited a few art galleries. We joked about how we’d both developed taste. Then we went back to our room and pulled up some of our early websites. We had a good laugh at who we used to be. Just two kids from a small town in Pakistan, who escaped their conservative families. Who dreamed something together. And just kept going. The dream kept changing, but we kept going. And look at us now. Look where we are. And look who we’ve become.”

(9/11) “Our visas were set to expire in three months. In order...

(9/11) “Our visas were set to expire in three months. In order to renew them, we’d have to show progress. But our sales were flat. And we’d failed to raise any money. So we thought for sure we were going home. We tried not to despair. We said: ‘Look where we are. We can’t squander this chance.’ We reached out to Pakistani investors, and they wrote us small checks. This bought us a little bit of time. But we had to face some hard truths. From the very beginning, our focus had been making leather dress shoes. But nobody wanted to wear them. Even in the business world, fashion was becoming more casual. So we had to start over. We had to begin from zero and find out what people wanted. So we pretended to be college students working on a project. We went to shoe stores and interviewed the managers. Then we interviewed the customers. We learned that people were looking for shoes they could wear every day, not just on special occasions. We researched the highest quality materials, and we put all of our findings into a document called ‘Ideal, Everyday Shoe.’ Then we gave all our notes to a talented designer. Together we built a prototype, and we called them ’Atoms,’ because we’d gone to the atomic level in search of quality. And to be honest we wanted a five letter name like ‘Apple.’ Our final hurdle was to test the product on customers. We sent out emails to our entire network. We wrote that we’d invented a shoe for ‘Hackers and Painters,’ but that we only had one size. So we were looking for people with size 10.5 feet. Twenty volunteers agreed to meet at our apartment. Everyone got a cup of Pakistani chai, then one by one we took them downstairs to try on a pair of shoes. Our first volunteer was an entrepreneur named Jason. He had a reputation for wearing high quality clothes. When we handed him the shoes, he began to study them carefully. My heart was racing the entire time. Then he put them on slowly, stood up, and began to walk across the room. His eyes got very big. ‘Oh, my God,’ he said. Then he jumped in the air, and he said it again: ‘Oh, my God.’ I looked at Waqas, and he was smiling. I was smiling too. Because both of us knew we were onto something big.”

January 28, 2021

(8/11) “The interview for Y-Combinator was a disaster. My...

(8/11) “The interview for Y-Combinator was a disaster. My internet was so slow that Waqas was forced to put me on mute. We knew this would be a giant red flag, since we were claiming to be a technology company. And we were already planning to try again next year. But later that night we received a call, telling us our application had been accepted. It felt like we were dreaming. But there was no time to celebrate, since classes were scheduled to begin in one month. There ended up being a problem with my visa, so I didn’t arrive in San Francisco until the very last minute. The orientation was held in a giant auditorium. There were hundreds of people, and everyone seemed to know each other. It was difficult not to doubt ourselves. Most of the attendees had gone to Harvard or Stanford, and some were building their 2nd and 3rd start-up. We carried a shoebox with us everywhere and sold shoes to the other attendees. Many people couldn’t understand our accent, but everyone seemed interested in our story. Every Tuesday we’d meet together as a group, and each company would report on its progress. We’d talk about the challenges we faced and the things we’d been able to accomplish. It seemed like every other company was focused on growth. They’d report how their revenues had grown 5 percent, or 10 percent. But Waqas and I were just trying to survive. We were struggling to fulfill the orders from our Kickstarter campaign, and each day brought a new problem with our production back in Pakistan. At the end of three months there was a big event called Demo Day. It was our final exam of sorts. Investors were invited from all over the world, and each company was given five minutes to present their vision on stage. We rehearsed our presentation for weeks. Our friends helped us with the design. And on the day of our presentation we felt very confident. But after it was finished, only two investors requested a meeting. And neither of them were ready to invest. We were the only company in our group who didn’t raise money. And to make matters even worse, it had been a formal event. Many of our classmates had dressed up. But none of them were wearing the shoes we had sold them.”

(7/11) “All of our customers came through word of mouth. First...

(7/11) “All of our customers came through word of mouth. First it was friends. Then it was friends of friends. After a year we were selling about 50 shoes per month. We were happy to have any business at all, but it wasn’t nearly enough to survive. And every week seemed like it would be our last. Our final hope was to launch a Kickstarter campaign. Our campaign launched on a Monday night. We set the goal at $15,000. Then we emailed the link to everyone in media and went to sleep. When we woke up the next morning, our goal had already been reached. Many blogs had decided to write about us, so orders were flowing in from all over the world. Waqas received so many calls from his family. Every day they would congratulate him on our progress. They’d say: ‘We are watching. And we are praying for you.’ But my parents never saw it. It was always: ‘We’ll look tomorrow.’ But they never did. At the conclusion of our campaign, we were the largest Kickstarter in the history of Pakistan. We sold over 600 pairs of shoes and raised $107,000. Finally I received a call from my mother. She said: ‘Now that you’ve raised all this money, it’s time for you to get married.’ Waqas wasn’t ready. He wanted our business to be stable. But I couldn’t bear the pressure any longer. I threatened him a bit. I told him it was going be him or somebody else, and he finally agreed. A normal Pakistani wedding lasts for five days, but we held our ceremony in a single afternoon. I went to the salon. Waqas took a bath. And afterwards we went to work. We didn’t have a honeymoon. There was no time to celebrate. Or take a rest. For the first time ever we had some momentum, and we were terrified to lose it. One of the first things we did was apply to an accelerator program in San Francisco called Y-combinator. It was the most famous program in the world. The admissions process was more selective than Harvard, and they’d helped launch companies like AirBnB and Dropbox. On our application we wrote that we intended to build an online platform for craftsmen all over South Asia. We knew it was a long shot. But we also knew that if we were somehow accepted, we’d be able to scale our company in the United States.”

(6/11) “I returned to the workshop a few weeks later. Once again...

(6/11) “I returned to the workshop a few weeks later. Once again the craftsmen offered me a chair, but this time I refused. I sat next to them on the muddy floor, and said: ‘Teach me everything you know.’ I wanted to learn it all: how to measure, how to make a pattern, how to tell the quality of leather. These men had been making shoes since they were kids, and I’m not sure they’d ever met someone so interested in their craft. They probably expected me to stay for thirty minutes, but I was there until the sun went down. And I came back seven times after that. In the end we agreed to collaborate on a collection. We would design the shoes together, and then market them on the internet. Waqas built our website while I focused on production. At first I trusted the experience of the craftsmen. But when our very first samples came in, I wasn’t satisfied. The quality was not the highest level. So I became much more involved. But I was careful not to criticize. It was more of a learning energy: ‘We can do better. We can figure this out.’ I’d insist on more stiches per inch. And better finishing. I’d bring in pictures of high quality, Italian shoes. And whenever the men told me that something couldn’t be done, I’d find a YouTube video showing how to do it. After several attempts we were able to produce a shoe of the highest standard. It was no different than what was being sold in expensive stores. We called our collection ‘Hometown Shoes.’ And after we launched our website, the first order came in right away. It was from a person in France who’d been following our story on social media. Because we had no way of accepting credit cards, he sent us $85 through Western Union. It was a very big moment for us. We had finally discovered a business that would work. But our excitement only lasted until we got to FedEx, and learned that shipping would cost $120. We were torn about what to do. We considered giving the man a refund, but we had been reading so much about customer service. So we ended up shipping the shoes. It was not a promising start. We’d lost a lot of money on our very first sale.”

(5/11) “Waqas had begun to view me as more than a business...

(5/11) “Waqas had begun to view me as more than a business partner. This was obvious to me. And maybe I was interested too, but I knew it wasn’t possible. Waqas was younger than me, and from a different caste. Neither of our parents would allow the match. But he was persistent. Nobody ever paid attention to me like he did. If we ever had some extra money, he’d bring me little gifts. And he always brought me water in a glass, never a cup. Every time we rode a bike together, he would wait until I was completely set. He’d make sure that my head was covered. And that my dress was pulled away from the wheels. These seem like small things, but nobody had waited for me to be set before. Waqas had been very close to his mother growing up. They used to read stories together from a woman’s digest, and I think that’s where he got his ideas of romance. Sometimes he’d want to give me hugs. Or hold hands. Or read poetry. But there was a shyness there, for both of us. Because in our culture these things are forbidden. One time we were walking in the park and he stopped to buy me flowers from a roadside vendor. But he was too nervous to give them to me, so he carried them all the way home. Then he threw them off the balcony. We never discussed the status of our relationship, but both of us could feel a closeness. We were bonded by our journey. Both of us were defying our parents. Waqas had dropped out of school without telling anyone, so neither of us could afford to turn back. But after a year of rejection we had begun to lose hope. We were looking for clients in the strangest places. One afternoon we met with a group of craftsmen in a small village. They were making leather shoes on the floor of a two-room workshop. It wasn’t the nicest environment, but the product was good. So we told them how the Internet could revolutionize their business. At first they were skeptical. It was clear to me that they had never worked with a woman before. They wouldn’t even look me in the face. And they insisted I take a chair, even though everyone else was sitting on the floor. When we left that day, I asked Waqas to arrange one more meeting. But this time I would come back alone.”

Brandon Stanton's Blog

- Brandon Stanton's profile

- 768 followers