Brandon Stanton's Blog, page 163

August 28, 2016

(5/6) “I knew the moment Mark came home. The general was with...

(5/6) “I knew the moment Mark came home. The general was with him. That morning I’d seen on the Internet that two soldiers were killed in Iraq. I immediately walked into the bathroom, and Mark was shaving, and I asked him if he thought it could be Jeff. He told me: ‘No way. We’d know by now.’ So when Mark came back home a few hours later, I knew. I started finding pictures of the boys together, and spreading them out on the table. I kept thinking: ‘The boys are together, the boys are together, the boys are together.’ I think I freaked out General Valcourt. He probably thought I was crazy. But saying those words was the only thing holding me together. The boys had always been so close. They were best friends as well as brothers. They did everything together. They even joked that they’d build their houses together, and share a pool, and share a dog. After Kevin’s death, Jeffrey always told me: ‘Don’t worry Mom. He’s with me. I can feel it.’ All of us kept journals when Kevin died. The grief counselor recommended it. But Jeffrey was the only one who kept it up. He addressed every entry to Kevin. They shipped us Jeffrey’s journal when he died, and the last thing he’d written was: ‘I’ll be in touch.’”

(4/6) “Jeffrey was set to deploy not long after Kevin’s death....

(4/6) “Jeffrey was set to deploy not long after Kevin’s death. I begged him not to go. I remember we went on a walk, and he said to me, in this real mature voice: ‘Dad, you know I have to go. My men need me.’ And I said: ‘Jeff. You don’t have to go. We need you here. Mom needs you, Melanie needs you, and I need you.’ But he insisted. I was a colonel at the time. And even though the father in me couldn’t understand, the soldier in me did. Jeffrey had to make his own path. He left for Iraq on Kevin’s birthday—November 15th, 2003. He was killed three months later. On that morning my boss was scheduled to leave on a trip. He was a two star general. We spent the morning together, then he told me ‘goodbye,’ and I assumed he left for the airport. But a few minutes later, I stepped into his office, and I found him standing alone in the dark. I said: ‘Sir, did you miss your plane?’ And he started walking toward me. And I knew. I knew when he took that first step. And he grabbed me, and he said: ‘Mark, it’s Jeff.’ And I said: ‘Is he hurt?’ And he told me: ‘Mark, he’s gone.’ And I said: ‘Are you sure?’ And he said: ‘I’ve known all morning. I verified three times.’ I thought ‘No, no, no, no, no. This can’t be. This isn’t possible. Not both of them.’”

(3/6) “I lost my dad when I was eleven. So I know what it...

(3/6) “I lost my dad when I was eleven. So I know what it means to be sad. I just didn’t know that you could die from being too sad. Kevin called us the night before. He hadn’t been sleeping. He’d been up all night playing this game called Sim City, and he’d just beaten the game. He’d become a four star general or something, and his friends were so happy for him, but he sounded so sad. He said: ‘I did everything the world says is success, but it’s not all it’s cracked up to be.’ Then he quoted Henry David Thoreau– that line about the masses living lives of quiet desperation. And he was crying. And I said: ‘Kevin, I’m so proud of you. I’d be proud of you even if you were digging ditches. If it’s the Army, drop out. I’ll pay back the scholarships.’ But he told me: ‘Dad, I can’t quit. It’s the soldier’s creed.’ So I just told him that I loved him. And that was the last time we spoke. We got a call the next night from Jeffrey. They were living together at the time. Jeffrey was hysterical. He said: ‘Dad. Kevin’s gone!’ I said: ‘What do you mean? Gone?’ And he said: ‘Kevin’s dead! He hung himself!’ And I just started screaming: ‘No! No! No!’ And I told Carol what happened. And she wasn’t crying. I remember feeling scared that she wasn’t crying. She just fell on the floor and started crawling to the living room. She was trying to get to her Bible.”

(2/6) “The Army was different back then. You have to remember,...

(2/6) “The Army was different back then. You have to remember, we had all those years of peace. For us it was swim meets and soccer games. Mark signed up to coach all the kids’ teams. He didn’t want to miss a moment with them. We had three children. Jeffrey was our oldest, then Kevin, then Melanie. Jeffrey was a leader like his Daddy. He wanted to build things. He erected tents in the living room. He slept in a sleeping bag. But Kevin was different. He was the tenderhearted one. He felt the pain of the world. I remember how shocked he was when he learned about slavery in school. He couldn’t even eat when he learned about the Holocaust. Jeffrey would always say: ‘Kevin! Stop thinking so much! Let’s go play soccer!’ But Kevin always felt like he had to figure out the world. He was our smart one. He wanted to be a doctor. He got two scholarships to college. He was the top cadet in ROTC. I knew that Kevin struggled with sadness. But I just gave him a bunch of Mom advice: ‘exercise more, ‘sleep more,’ ‘eat more vegetables.’ I tried to pray it away. I wrote letters to God, asking to lift Kevin’s ‘spirit of depression.’ And we didn’t tell anyone. I thought: ‘He’s doing so well in school. Don’t rock the boat.’ We kept it a secret. So I think we share in what happened.”

(1/6) “We met in college. Mark had long hair and a beard. He...

(1/6) “We met in college. Mark had long hair and a beard. He was class president so there were posters of him hanging up around campus. He was really cool. I was kind of ‘not cool.’ I played saxophone in the band. I was a Christian. Neither of those things was very cool in the 70’s. I tried to impress Mark by participating in a blood drive that he was organizing. I ended up passing out and they had to wheel me out in front of the rest of the students. But we started dating eventually. Everything happened so fast after that. We got married when we were twenty-one. When he proposed, Mark told me: ‘I just want you to know that I probably won’t live long.’ His father had died of a heart attack at the age of thirty-one, so Mark was convinced that he’d die young too. Neither of us ever dreamed it was our boys we would lose.”

August 25, 2016

“We were built to think alike. Everything is so standardized...

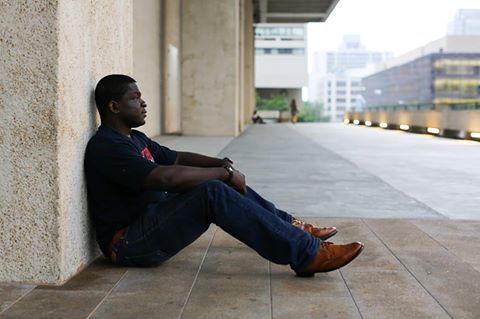

“We were built to think alike. Everything is so standardized in the military that you can function without thinking. If I ever needed night vision goggles, somebody could throw me their bag, and I’d know exactly what pocket to find them in. We were like cogs in a wheel. And that may sound like a bad thing—but it’s not. Nobody wants to think of themselves as cogs in a wheel, but humans love structure. Our behavior is predictive. All of us tend to be in the same place, at the same time, every single day. The tendency is just accelerated in the military. And it feels good. It feels good to know your place. It feels good to wear the same uniform. It feels good to know exactly what you’re contributing to the mission, to the team, and to the country as a whole. Your value is so clear. But then you come home and the lines are blurred. It’s hard to discover that value again. You’re not sure where you fit. You’re not sure how you connect to other people. You’re not sure how to make a difference. It can be very isolating. And all you want to do is be back on a team.”

August 24, 2016

“I don’t feel good about it. It will bother me for the rest of...

“I don’t feel good about it. It will bother me for the rest of my life and honestly I’m happy about that. I’m embarrassed by how little I knew. I was a kid from Texas. I flew on a plane for the first time when I went to boot camp. I had this visceral desire to seek vengeance for 9/11, and I believed our government when they told me that there was a connection to Iraq. So I fully supported the war. I thought we were bringing bad people to justice. I didn’t understand the nuances. I didn’t know anything about the people of Iraq, or the culture, or the country. And I feel ashamed about that. I’m getting my graduate degree in Middle Eastern history right now. And the more I learn, the worse I feel. I got so much personal benefit from being in the military. In many ways it was the greatest thing I’ve ever done. But I could have gotten those personal benefits from other means. I was in Iraq for one year. And the trauma of that year will impact me for the rest of my life. But for the people of Iraq, it’s been ten years. And they’re still being traumatized on a daily basis.”

August 22, 2016

“I have professors at Columbia who view me as a terrorist for...

“I have professors at Columbia who view me as a terrorist for fighting in Iraq. But I believe that America is an example to be emulated, and I went over there to provide those people with basic human freedoms. But when you get over there you realize that you’re fighting kids. Everyone was kids. You see it when they’re dead. These weren’t the guys who were flying into towers. These were kids who grew up poor, stepped into the wrong madrasa, and were manipulated by people with a shit load of money into executing somebody else’s worldview. None of them came out of the womb hating. None of them came out of the womb thinking anything else but holy shit this is a bright beautiful world.”

August 21, 2016

(2/2) “In Afghanistan I spent so much time imagining what it...

(2/2) “In Afghanistan I spent so much time imagining what it would be like when I came home. I built up this perfect world. I imagined eating a big cheeseburger. And taking the longest shower. And meeting up with all my friends. Maybe we’d even take a trip to the beach just to catch up. And everything would be just like when I left. And people would be so happy to see me. Because they’d be thankful for the sacrifices that I made. But when my plane landed, nobody was there to meet me. My mom couldn’t afford to take off work. My father had died while I was gone. The rest of my family couldn’t afford to travel. One of the first things I did was visit the two friends who had written me letters. The whole time I was in Afghanistan, I only got four letters from two friends. So I had to visit them right away to tell them that those letters meant the world to me. But after those visits, I was pretty much by myself. So I sat in my room and I started thinking. I’d been so busy in Afghanistan. There was always a job to do. But now it was quiet. So I thought about all the things that I’d kept at bay. I thought about the little girl that I saved. And what her life is like now. And I wondered if she’s still alive. And if she is still alive, does she even want to be?”

(½) “ I don’t think it’s possible to be a medic in a...

(½) “ I don’t think it’s possible to be a medic in a conflict zone and not have something stay with you. Something that you didn’t have before you went. I have the hardest time forgetting this little girl. She was brought to our post one day. Two men ran toward us carrying a bundle of blankets. And they’re yelling in Pashtu. And at first all I can see are these bloody blankets, but then I peel them back, and there’s this little girl inside. She stepped on a landmine while playing soccer and she’s gone below the knee, gone below the elbow, gone below the hand. And everything is seething. And I can smell the flesh. And she’s screaming. But I’m trained to drown it out. I’m trained so well that I almost don’t hear the screaming. I focus on our interventions. Stop the bleeding. Apply tourniquets. Administer the IV. I overdosed her on morphine. I’ll never forget that. I just kept pushing until the screaming stopped. And then a helicopter came and got her. And she lived. And I was fine throughout the whole thing. I was just like a robot. I’d been trained for chaotic situations. But they don’t train you for the aftermath. They don’t train you for when the helicopter has lifted off, and suddenly everything is quiet.”

Brandon Stanton's Blog

- Brandon Stanton's profile

- 769 followers