Vered Neta's Blog, page 2

June 29, 2025

BOOK VS. TV SHOW: His Dark Materials.

Years ago, when the movie The Golden Compass came out, my daughter and I went to the cinema to watch it on the big screen. We loved it, waiting forever for the next chapter to unfold, which it didn’t (Thank God).

However, when “His Dark Materials” was turned into a TV show, I was reluctant to watch it as, by now, I had read the books and doubted that it would be able to capture the story. It had to wait until my grown-up daughter came to visit a few weeks ago for me to give the show a second chance, finally

Every so often, a screen adaptation doesn’t just do justice to a beloved book — it surpasses it. That’s a rare alchemy, especially when the source material is as celebrated as Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials. But in this case, the HBO/BBC series doesn’t just bring the world of daemons, Dust, and armoured bears to life — it deepens, sharpens, and elevates the story in ways the original trilogy sometimes struggled to achieve.

Let’s dive into the multiverse, shall we?

The Books.

The Books.For those of you who may not be familiar with Philip Pullman’s work, His Dark Materials is a trilogy that takes readers on a philosophical rollercoaster through parallel worlds, mysticism, and childhood wonder.

The trilogy—Northern Lights (aka The Golden Compass), The Subtle Knife, and The Amber Spyglass—is a genre-defying epic that combines fantasy, theology, philosophy, and coming-of-age adventure with daemons, witches, and parallel worlds.

It begins in a steampunk-ish alternate Oxford, where we meet Lyra Belacqua — a wild, whip-smart girl raised by scholars. Her journey starts small, searching for a kidnapped friend, but quickly spirals into a cosmic adventure. We’re talking evil institutions, talking polar bears, knife-wielding boys from our world (hello, Will Parry), angels, spectres, and a war against a tyrannical Authority that may or may not be a stand-in for God.

It’s sweeping, it’s bold, it’s weird, and it’s very British. It challenges readers to think big while staying rooted in the emotional truths of growing up. But while Pullman’s ambition is undeniable, the storytelling sometimes strains under the weight of its own ideas, and that’s where the TV adaptation truly shines.

[image error]My ReviewThe Books – Rich in Ideas, Sometimes Wobbly in Execution.

Philip Pullman is no ordinary fantasy writer. His books ask big questions: What is the soul? What if the Church wasn’t a beacon of light, but a machine for control?

What if growing up meant not just learning facts but discovering moral truth?

Plot: Daring but Occasionally Drifting.

The trilogy starts strong with Northern Lights, a book full of momentum, mystery, and discovery. Pullman creates an atmospheric world brimming with intrigue — Jordan College feels ancient and cloistered, the North is full of danger and wonder, and Lyra’s journey feels both intimate and epic.

Every chapter teases something bigger, drawing you in with childlike curiosity.

However, by the time we reach The Amber Spyglass, the plot gets tangled in its own ambition.

Pullman juggles too many threads — angels and rebel factions, interworld travel, philosophical debates about consciousness, and an entire subplot set in the land of the dead. Instead of escalating tension and emotional payoff, the pacing slows, and key moments get buried under exposition.

You admire the scope, but the story’s propulsion sometimes suffers.

Characters: Lyra and Will Shine, Others… Not So Much.

Characters: Lyra and Will Shine, Others… Not So Much.

Lyra Belacqua (Silvertongue) is a dazzling creation — fiercely curious, often reckless, but always brave.

Her growth from wild child to morally grounded adolescent is deeply moving. When Will Parry joins the narrative, his contrast to Lyra — all quiet strength and deep sadness — adds the emotional ballast the series needs. Their bond is one of the trilogy’s most affecting elements, offering a rare depiction of first love that feels both innocent and profound.

However, not all characters receive the same depth. Lord Asriel’s motivations are epic but emotionally distant, and Mrs. Coulter, though fascinating, often reads as inconsistent, oscillating between maternal tenderness and sadistic cruelty without much introspection. Supporting characters like Lee Scoresby, John Faa, and even Mary Malone serve functional roles but rarely transcend archetypes.

Pullman’s philosophical lens sometimes flattens the emotional complexity of these figures.

Themes: Brave, Bold, Occasionally Blunt.

Themes: Brave, Bold, Occasionally Blunt.

One of Pullman’s greatest strengths — and weaknesses — is his commitment to Big Ideas.

His trilogy is, at its core, a rebuke of dogma and a celebration of free will, curiosity, and moral complexity.

The Church, reframed as the Magisterium, becomes the story’s antagonist not because it represents faith, but because it stifles thought and suppresses truth.

But sometimes, these themes become sledgehammers. Dialogue veers into polemic, and entire chapters read like lectures. In The Amber Spyglass, characters pause the action to discuss metaphysics, consciousness, and the nature of Dust in ways that, while intellectually stimulating, slow narrative momentum.

The story risks alienating readers who came for daemons and adventure but found theological density instead.

Writing Style: Gorgeous in Places, Dense in Others.

Pullman’s prose can be magical, especially when describing the North, the shimmering aurora, or the intimacy between human and demon. He evokes awe and melancholy with elegance, capturing the fragile beauty of childhood and the gravity of growing up—for instance, the scenes of Lyra reading the alethiometer pulse with mystery and intuition.

But this lyricism is often interrupted by scientific jargon or abstract philosophy. Readers can be yanked from emotional immersion into cerebral dissection.

The balance between showing and telling occasionally falters, particularly in the final book. It’s not that the ideas aren’t interesting — they are — but the delivery sometimes prioritises intellect over feeling.

TV Show

TV ShowThis isn’t the first attempt to bring Pullman’s world to the screen. Remember, I mentioned watching the 2007 Golden Compass movie?

That version was so sugar-coated and afraid of offending anyone that it stripped the story of its soul.

Enter the HBO/BBC adaptation, which aired between 2019 and 2022.

It took its time — three seasons for three books. With a stellar cast, cinematic production values, and sharp writing, the series took the very best of Pullman’s vision and made it more accessible, emotionally resonant, and — dare we say it — fun.

A World That Feels Real.

A World That Feels Real.

The adaptation excels at worldbuilding through visuals. Jordan College isn’t just described; it’s rendered in sandstone and shadow.

Svalbard’s icy expanse looks hostile and lonely. The city of Cittàgazze feels sunlit but cursed, its abandoned piazzas echoing with danger.

Every location feels specific and lived-in, thanks to production design that combines realism with whimsy.

The daemons, a central aspect of Pullman’s mythology, are handled with care. They feel organic—never too CGI, never too distracting. Pantalaimon’s subtle movements and expressions convey just as much emotion as Lyra’s face does.

The show also wisely uses sound design and music, creating an atmosphere that mirrors the emotional weight of the story. It’s immersive without being overbearing.

[image error]Characters You Can Feel For.

One of the adaptation’s strongest suits is its cast and the nuanced direction they receive. Ruth Wilson’s Mrs. Coulter is nothing short of a revelation.

She embodies cruelty and charisma but also maternal yearning and internal war. Her complex relationship with her daemon becomes a recurring motif for self-loathing and repression.

James McAvoy’s Lord Asriel is thunderous and messianic, while Lin-Manuel Miranda offers a charmingly American take on Lee Scoresby that injects levity without undermining gravitas. Dafne Keen and Amir Wilson are magnetic as Lyra and Will.

Their performances deepen the emotional truth of their relationship, anchoring the fantasy in real adolescent vulnerability. Their parting at the series’ end is gut-wrenching — not because of melodrama, but because it’s quiet, inevitable, and profoundly human.

Changes and Additions.

Changes and Additions.Smart Narrative Choices.

The show makes several critical structural improvements:

While this creates intimacy, it also limits the reader’s understanding of the wider world and the many forces at play.

The series, however, opens up the narrative — introducing Will Parry much earlier and weaving in the perspectives of characters like Mrs. Coulter, Lord Asriel, and Mary Malone. This broader lens not only deepens the stakes but also makes the world more dynamic and interconnected, allowing viewers to emotionally invest in a wider array of characters from the start.

The Magisterium is nuanced, portrayed not as cartoonishly evil but as an institution built on fear, power, and misguided righteousness.

Mary Malone’s journey, including the Mulefa and her “serpent” role, is rendered visually and thematically with care, making even the strangest elements feel grounded.

[image error]Supporting Characters Step into the Spotlight.

The series excels at expanding its ensemble. Characters who were once footnotes now breathe with interiority. Ma Costa (Anne-Marie Duff) becomes a fierce matriarch, and her love for Lyra is both protective and empowering.

John Parry (Andrew Scott) is transformed from the narrative device into a tragic figure whose reunion with Will is one of the show’s most emotionally satisfying scenes.

Farder Coram (James Cosmo) and Serafina Pekkala’s (Ruta Gedmintas) romantic history adds layers to their political alliance, while Ruta Skadi is given more apparent motives and more screen time.

Even Mary Malone’s (Simone Kirby) journey through the Mulefa world — one of the more eccentric parts of the books — is rendered with warmth and visual grace. By centring these characters, the show transforms Pullman’s epic into an emotional mosaic.

The Magisterium Gets a Makeover.

The Magisterium Gets a Makeover.

Unlike the 2007 film adaptation, which sanitised the religious critique, the TV series leans into the Magisterium’s authoritarian menace. But it does so with nuance.

The Church isn’t demonised wholesale — instead, we see the internal politics, power struggles, and justifications of its leaders.

Father MacPhail is terrifying not because he’s evil, but because he believes he’s righteous.

This shift reframes the conflict not as science vs. religion, but as curiosity vs. control.

It aligns the viewer with characters who seek truth, compassion, and autonomy, making the story’s philosophical stakes feel more urgent. The show trusts the audience to grapple with moral complexity — a fitting tribute to Pullman’s own ideals, but executed with more subtlety.

Better Emotional Payoffs.

Better Emotional Payoffs.

Perhaps the greatest triumph of the show is its emotional intelligence. It strips away some of the cerebral detours of the books and foregrounds human feeling.

Small gestures — like Lyra hugging her daemon, or Will’s quiet tears — carry as much weight as any battle or prophecy.

The choice to end with Lyra and Will sharing a bench in the Botanic Garden is pitch-perfect.

The final scene, where Lyra and Will sit on the same bench in separate worlds, distils heartbreak.

There’s no need for grand declarations; the silence speaks volumes. It’s a mature, restrained ending that honours the tragedy of choice and the beauty of memory—themes that the books gesture at but the show fully realizes.

Verdict

VerdictI’m not saying Pullman isn’t a genius. He created a world that’s rich, layered, and unlike anything else in fantasy.

But sometimes, genius benefits from a little collaboration.

The TV show trims the philosophical fat, deepens the characters, and delivers a story that’s coherent, emotional, and visually stunning. It doesn’t just translate the books — it elevates them.

So if you’ve read the books and felt overwhelmed or underwhelmed at times, give the show a chance.

It’s the best version of His Dark Materials — daemons, Dust, heartbreak, and all.

And if your daemon disagrees? Well, that’s between you and your inner snow leopard.

Now it’s YOUR turn – Team Book or Team Show — which version won your heart and why?

Would love to get your input in the comment box below.

The post BOOK VS. TV SHOW: His Dark Materials. appeared first on Vered Neta.

June 22, 2025

What Happened to Classic Romance Tropes?

Ah, romance. The heart-fluttering backbone of countless stories across books, films, and TV.

Whether you’re a sucker for the slow burn or roll your eyes at love-at-first-sight, there’s no denying that romantic tropes are like comfort food: familiar, predictable, and oh-so-satisfying… until they’re not.

In recent years, storytelling has undergone a massive transformation. Audiences are demanding more depth, more nuance, and more authenticity. And romance? Well, it’s been forced to grow up. Let’s dive into how romantic tropes have evolved, why it matters, and how storytellers are reshaping the way we fall in love on page and screen.

From Fairy Tales to Fanfiction: A Brief (and Slightly Cheesy) History.Let’s rewind. Once upon a time, romance was ruled by a few tried-and-true tropes: the damsel in distress,

the brooding hero with a tortured past, love triangles that made zero sense, and happy endings wrapped up with a wedding and a kiss. Cue the orchestral swell, the kiss, and fade to black.

Think of Cinderella and her glass slipper. Or Elizabeth Bennet and Mr. Darcy finally declaring their love under the English rain. Or, let’s be honest, the endless “he saves her, she softens him” formula.

But culture changes. And with it, so do our love stories.

Why Tropes Matter (Even When They’re Cringe).Before we start slamming tropes, let’s give them their due. Tropes are not inherently bad.

They’re storytelling tools—shortcuts that communicate complex emotional arcs efficiently.

The enemies-to-lovers arc gives us tension and growth. The second-chance romance brings in regret, maturity, and hope. The friends-to-lovers trope? Pure heart-melting nostalgia.

The problem? When tropes become predictable, lazy, or—worse—outdated. And for a long time, romantic stories were stuck in heteronormative, gender-stereotyped mud. Enter: the modern storyteller with a trope-defibrillator and something new to say.

Tropes That Got a 21st-Century Makeover.Here’s where it gets juicy. Let’s look at some classic tropes and how they’ve evolved:

#1 – Enemies to Lovers.

Then: Think Pride & Prejudice or 10 Things I Hate About You. Classic bickering, then swooning.

Now: Today’s enemies-to-lovers often deal with real ideological clashes, not just petty squabbles. Take The Hating Game (book and movie). The tension is steamy, sure—but it also explores workplace dynamics, ambition, and emotional vulnerability.

Even better, look at Bridgerton’s Kate (Simone Ashley) and Anthony (Jonathan Bailey).

The Regency-era constraints are still there, but the show adds layers of cultural identity, repressed trauma, and mutual respect. The enemies trope here isn’t just foreplay—it’s character growth in disguise. Kate and Anthony don’t just argue—they challenge each other’s deepest fears and assumptions.

#2 – Love Triangles.

#2 – Love Triangles.

Then: Twilight and The Hunger Games gave us endless “Will she choose brooding or sweet?” debates.

Now: The love triangle is slowly being retired or subverted. Why? Because audiences have outgrown the idea that romantic fulfilment hinges on choosing the right guy (or gal).

Netflix’s Never Have I Ever started with the classic two-boy triangle, but it ended by focusing on Devi’s (Maitreyi Ramakrishnan) self-worth and growth.

And in Greta Gerwig’s Little Women, Jo (Saoirse Ronan) turns down Laurie (Timothée Chalamet) —not for a better match, but to follow her creative calling.

#3 – The Manic Pixie Dream Girl / Knight in Shining Armour.

Then: She was quirky! He was broody! She saved him with ukuleles and weird hats! (Garden State, I’m looking at you.)

Now: This trope is being called out,

re-examined, or flipped on its head.

Take 500 Days of Summer. Tom (Joseph Gordon-Levitt) projects all his fantasies onto Summer (Zooey Deschanel) —until the film brutally (and brilliantly) shows us that she was never the “dream girl,” just a woman with her own agency.

Or Palm Springs, where the female lead (Cristin Milioti) has her own pain, agency, and transformation arc.

She is the one solving the time loop and pushing emotional change, not just tagging along for the ride.

#4 – Fake Dating.

Then: A lighthearted setup leading to real feelings. Usually cute, a little silly, and somehow always ending with a dramatic declaration.

Now: Fake dating still exists (and we love it!), but it’s being used to explore deeper emotional themes.

In To All the Boys I’ve Loved Before, Lara Jean (Lana Condor) and Peter’s (Noah Centineo) pretend relationship feels authentic because it taps into the vulnerability of teen identity, family dynamics, and self-discovery.

Red, White & Royal Blue explores what it means to hide love in a world that isn’t always safe.

New Tropes for a New Era.Some tropes didn’t exist a decade ago, but they’re fast becoming staples of modern romance.

Here are a few:

#1. “It’s Complicated” Romances.

#1. “It’s Complicated” Romances.

Forget fairy-tale neatness. Today’s romances lean into ambiguity.

These are stories where love is real, but it doesn’t necessarily lead to a relationship, or at least not a permanent one.

In Normal People, Connell (Paul Mescal) and Marianne (Daisy Edgar-Jones) are deeply connected, but emotionally ill-equipped.

The story doesn’t reward us with a tidy ending. Instead, we see love as a force that changes people, even when it doesn’t last.

Similarly, in Past Lives, the central question isn’t “Will they get together?” but “What would have happened if they had?” The beauty lies in longing, in what’s unsaid, and in accepting that love doesn’t always equal destiny.

This trope reflects the reality that modern relationships are often nonlinear, marked by missed opportunities, timing issues, and personal crossroads.

#

2. Healing Romances.

#

2. Healing Romances.

These stories don’t start with passion—they begin with pain. And instead of one partner saving the other, both characters are healing, often from trauma, grief, or past relationships. The romance isn’t the goal—it’s the container for mutual growth.

In Ted Lasso, Roy (Brett Goldstein) and Keeley (Juno Temple) both carry emotional wounds. Their love story is built not on grand gestures but on quiet support, difficult conversations, and making space for each other’s healing. It’s messy, human, and real.

In Fleabag, the connection between Fleabag (Phoebe Waller-Bridge) and the Hot Priest (Andrew Scott) is intense but ultimately unsustainable, because it’s not about compatibility; it’s about awakening. Their brief love is the catalyst for Fleabag’s personal healing, not the prize.

These romances tell us: love can be transformative even if it’s not forever.

#

3. Second Chance, But Make It Therapy.

#

3. Second Chance, But Make It Therapy.

Second-chance romance used to be built on nostalgia. Now, it’s built on accountability.

Modern second-chance stories aren’t about rekindling what once was—they’re about facing who you’ve become.

Take Before Midnight, the third film in Richard Linklater’s Before trilogy. Jesse (Ethan Hawke) and Celine (Julie Delpy), once idealistic lovers, are now middle-aged parents grappling with resentment and the compromises that come with age. Their connection is still there, but love, at this stage, is work.

Or in The Bear, Carmy (Jeremy Allen White) and Claire (Molly Gordon) reconnect in adulthood, but the baggage they carry can’t be ignored. The “do-over” only works if both parties have done the internal work to change. Second chances now come with conditions: honesty, self-awareness, and yes, therapy.

#

4. “Self-Love Is the Real Love Story”.

#

4. “Self-Love Is the Real Love Story”.

The most radical romance today? The one you have with yourself.

While this isn’t a romantic trope in the traditional sense, it’s becoming a staple of modern storytelling. Characters who prioritise their identity, healing, and dreams over romantic resolution are the new leading ladies (and gents).

In Everything Everywhere All at Once, Evelyn (Michelle Yeoh) and Waymond’s (Ke Huy Quan) love story is told in fragments—through multiverses, regrets, and resilience. But the emotional climax is not just romantic. It’s about Evelyn choosing her own wholeness and learning to stay present, with herself and with her family.

In Lady Bird, the teen heroine has a crush, sure, but her most meaningful “love arc” is her reconciliation with her mother—and herself.

These stories teach us that the endgame isn’t always a relationship. Sometimes it’s becoming someone who no longer needs one to feel whole

# 5. Diversity, Queerness, and the Rise of “Real Love”.

The most refreshing evolution? Romance no longer looks the same.

Gone is the assumption that the central couple must be straight, white, cisgender, and conventionally attractive. Romantic stories are now intentionally inclusive, and that’s not just for representation—it’s for richer, more honest storytelling.

In Heartstopper, Nick (Kit Connor) and Charlie’s (Joe Locke) relationship unfolds with all the awkward sweetness of first love—only this time, it’s queer, joyful, and affirming.

In Rye Lane, we get a Black British rom-com that’s culturally specific yet universally resonant.

The new norm? There is no norm. Romance is for everyone.

# 6. The Myth of the “Happy Ending”.

Perhaps the most significant shift in modern romance is how we define a happy ending.

We’re no longer content with the kiss-in-the-rain and a fade-out. We want resolution, not fantasy. Fulfilment, not fan service. The best romantic stories today don’t ask, Did they get together? They ask, Did they become better because of each other?

In La La Land, Mia (Emma Stone) and Sebastian (Ryan Gosling) don’t end up together. But they do inspire each other’s dreams. That’s the win.

In The Leftovers, Nora (Carrie Coon) and Kevin (Justin Theroux) reunite—not with fireworks, but with aching honesty, choosing each other after years apart. That’s a happy ending, too. One built on truth, not tropes.

Final Thoughts – Love in the Age of Complexity.So, where are we now?

We’re in the era of conscious love stories. Romances that allow characters to be flawed, vulnerable, and unsure. Tropes still exist—but they’ve been seasoned with realism, diversity, and emotional intelligence. And honestly? They’re better for it.

Love is complicated. Messy. Sometimes absurd. But when stories reflect that complexity, they become more than just romantic—they become real.

So whether you’re writing a friends-to-lovers rom-com or bingeing the next heart-wrenching A24 drama, just remember: tropes aren’t the enemy. Stagnation is. Romance is alive and evolving—and we’re lucky to be watching it unfold.

Now it’s YOUR turn – What’s the most refreshing love story you’ve seen lately?

Would love to get your input in the comment box below.

The post What Happened to Classic Romance Tropes? appeared first on Vered Neta.

June 15, 2025

Breaking Down MAID – How MAID Nails TV Story Structure.

When I first dipped my toes into screenwriting, I had this idea—naïve, hopeful, wildly inaccurate—that writing a feature film would be easier than writing a novel. After all, how hard could it be to write 90–120 pages, compared to the sprawling 250–300 pages of a novel?

Boy, was I wrong.

The brutal beauty of writing a feature film is that it’s short. Yes, short. You’d think brevity would be a blessing, right? Nope. It’s a curse in disguise. Because with such a tight page count, everything has to be economical. Everything must be visual. There’s no room for internal monologue, pages of poetic musing, or backstory rambling. Every action, line of dialogue, and cut has to carry weight. I had to train myself in the sacred arts of structure, pace, and the elusive beast known as the “character arc.”

Just when I felt like I’d cracked the code—understood the rhythm of a three-act film structure and how to plant setups and payoffs—I decided to level up.

“I’ll write a TV pilot!” I declared with reckless optimism. And off I went to write the Pilot for “Crime Cleaners”.

And then came the crashing realisation: writing a TV pilot is a totally different ball game. If writing a feature film is a tightrope walk, then writing a TV series is building the entire damn circus—and directing the elephants.

The Fundamental Shift: From 3 Acts to 5 Acts.If you come from the world of novel-writing or even feature films, your brain is most likely wired to think in three acts: Beginning, Middle, End. Setup, Confrontation, Resolution. Act 1, Act 2, Act 3. It’s clean. It’s classic. It’s familiar.

But television, especially American drama TV, doesn’t always play by that rule. Particularly in network and limited series writing, episodes often follow a 5-act structure. These acts aren’t just for commercial breaks (though that’s where the tradition comes from); they’re a deliberate tool for pacing, tension-building, and juggling multiple storylines.

Here’s the twist: in every episode, you’re not just tracking one story.

You’re weaving three storylines simultaneously:

The B-story (often a subplot involving a secondary character or relationship),

The C-story (frequently comic relief, thematic counterpoint, or character development).

To understand how to write a Pilot and a full TV series, I watched many Pilots and mini-series (the type I wanted to turn Crime Cleaners into).

It was the best education I could imagine. It wasn’t just bingeing; it was a deep-down breakdown of each episode and series. The best one for me was MAID (Netflix 2021)

Created by Molly Smith Metzler and inspired by Stephanie Land’s memoir, MAID is a heartbreaking, raw, and often darkly funny exploration of poverty, abuse, motherhood, and survival.

From the very first frame, the pilot grips you, and as a writer, I couldn’t help but admire how precisely the storytelling unfolds.

Let’s break down the pilot episode of Maid using the 5-act structure and examine how the A, B, and C storylines are interwoven.

ACT I: The Catalyst.

ACT I: The Catalyst.

(Approx. 0:00–10:00)

Maid opens with a bang—emotionally speaking. Alex (Margaret Qualley), a young mother, wakes up in the middle of the night, grabs her daughter, and flees an emotionally abusive relationship.

It’s quiet. No bruises. No screaming. But you feel the danger.

This act introduces the central A-story: Alex’s quest to escape and build a better life.

B-story threads start to emerge subtly: we learn about Alex’s relationship with her eccentric, unstable mother, Paula (played brilliantly by Andie MacDowell, Margaret Qualley, real-life mother).

This sets the groundwork for emotional baggage and family dynamics.

The C-story (which in Maid is less comic and more reflective) begins to form in Alex’s interactions with the bureaucratic system—courts, housing, social workers—establishing the Kafkaesque absurdity of navigating poverty and abuse with no resources.

Act 1 ends with Alex being told she’s not eligible for housing assistance because she has no job.

A classic “door slams shut” moment—she’s escaped abuse only to land in the open water with no lifeboat.

ACT II: The Deepening Conflict.

ACT II: The Deepening Conflict.

(Approx. 10:00–25:00)

In Act II, Alex tries to “do the right thing.”

She seeks help. She applies for government aid.

She looks for work. We see her pride, her resourcefulness, her fear.

She takes a job cleaning houses—a huge moment that becomes a motif throughout the series.

This act deepens the A-story conflict: her struggle for independence while caring for her child.

The B-story develops with more scenes involving Paula, who’s loving but unreliable, caught up in her own version of reality. Alex’s attempts to rely on her mother for childcare lead to tension and reveal old wounds.

The C-story becomes clearer as Alex is forced to interact with a legal system that operates with cold logic, not compassion. We start to see the absurdity and inaccessibility of “the safety net.”

Act 2 ends with a setback: Sean (Alex’s ex) files for custody. A gut-punch that underscores that escape is not the same as freedom.

ACT III: The Reversal.

ACT III: The Reversal.(Approx. 25:00–38:00)

Here, we often see a glimmer of hope or a change in strategy. Alex, bruised but not broken, begins to find her footing. She’s allowed to stay at a domestic violence shelter. She begins work as a cleaner.

There’s a moment of tentative stability.

But remember: this is the midpoint, not the resolution.

The B-story brings us deeper into her past. Conversations with her mother and a flashback-like memory reveal that Alex’s own childhood was steeped in chaos. The generational cycle of trauma becomes visible.

The C-story (interactions with bureaucracy and clients) now adds new texture: one of her cleaning clients lives in an opulent house and leaves behind passive-aggressive sticky notes. It’s a bitter contrast to Alex’s precarious existence. It also signals class disparity without a single line of exposition.

Act 3 ends with a question: Can she keep all these plates spinning?

ACT IV: The Crisis.

ACT IV: The Crisis.

(Approx. 38:00–48:00)

Now comes the darkest hour. Alex begins to lose control. The shelter is temporary.

Sean is pushing harder. She’s exhausted. Her mother becomes erratic again.

The judge in the custody hearing treats her as the unstable one.

This act hits the audience emotionally: Alex is trying to do everything right, but the system is built to make her fail.

The B-story (her mother’s mental health and instability) comes to a boiling point—Alex can no longer rely on her for anything.

The C-story (bureaucratic absurdity) is now both tragic and ironic: a cleaner can’t afford cleaning products. She’s offered job training that requires daycare, but she can’t afford daycare without a job.

Act 4 ends with Alex realising no one is coming to save her.

[image error] ACT V: The Climax & Decision.

(Approx. 48:00–59:00)

Every pilot needs a strong ending—not a conclusion, but a promise. A question that makes you want to watch Episode 2.

In MAID, Act 5 delivers that.

Alex decides to stay at the shelter longer. She begins journaling. She cleans houses with more precision and purpose. She learns what “work” will cost her emotionally and logistically—but also how it will empower her.

The A-story reveals her resilience. The B-story shows her distancing herself from Paula, an emotional boundary we sense she’s never drawn before. The C-story becomes a mirror: the more houses she cleans, the clearer her own path becomes.

Act 5 ends with a choice, not a victory. And that’s why it works.

The series promises growth, struggle, and complexity, and we believe her story is worth following.

However, MAID also gives a masterclass on how to build a whole series. While each episode follows the classic TV format of three interweaving storylines the whole series is also a masterclass in the 3-Act movie structure stretched across 10 episodes.

Let’s break it down, popcorn-style.

ACT I: Set-Up, Inciting Incident (Episodes 1–3).

ACT I: Set-Up, Inciting Incident (Episodes 1–3).

Episode 1: “Dollar Store” – The Inciting Incident.

Bam. We open with Alex grabbing her daughter Maddy in the middle of the night and fleeing.

No backstory monologue, no courtroom drama. Just: GO. That’s your inciting incident right there.

The emotional punch is immediate. She doesn’t even know if she qualifies as a victim of abuse.

But she knows she has to leave.

This moment catapults us straight into survival mode. And MAID doesn’t waste time — it throws her into the maze of welfare offices, domestic violence shelters, and endless “you don’t qualify” catch-22s.

Alex is smart. But the system is a labyrinth.

Episode 2–3: Set-Up + Break into Act 2.

Alex lands her first cleaning gig — the titular “maid” job — and that becomes her first active goal.

Not just running from abuse, but trying to build something. That’s our Break into Act 2: she’s out of crisis mode and into the battlefield.

By Episode 3, she has her first real chance at independence — a client offers her a chance to write, even suggests college. This is the “I want more” moment, the promise that there might be a life beyond survival.

ACT II: The Long Battle (Episodes 4–7).

This is where MAID shines — it keeps the tension alive by never letting things be entirely tragic or fully hopeful. Every victory comes with a cost.

Fun and Games (if we can call it that): Episode 4–5.

Alex starts to feel some autonomy. She has her own place (okay, it’s moldy and barely livable, but still).

She’s getting cleaning gigs. She’s found a rhythm.

But this is MAID , not a rom-com.

Every step forward comes with a slippery floor. Her mom Paula is a brilliant chaos machine.

Paula is free-spirited, talented, and also deeply unreliable.

And then there’s Hank, Sean’s sponsor, that just “happens” to be Alex’s estranged father.

He’s not a hero, not a villain — but someone who understands addiction, who knows what Sean is capable of, and yet still tries to support Sean and not his own daughter. He’s a minor character, but you never forget him.

Midpoint: Episode 6 “M”.

Midpoint: Episode 6 “M”.

This is the heart of the series. The midpoint is where Alex finally acknowledges her abuse.

The court does too. She gets temporary custody. This episode is like a tiny, shining island in the storm.

She even gets accepted to college! There’s a light at the end of the tunnel.

But the show is called MAID, not Made It.

ACT IIIA: All Is Lost, Dark Night of the Soul (Episodes 7–8).

Right on schedule, everything comes crashing down.

All Is Lost: Episode 7–8.

All Is Lost: Episode 7–8.

Alex makes the mistake so many abuse survivors make — she tries to give Sean another chance.

It’s heartbreaking and honest. He’s sober. He seems better. For a moment, the family almost functions.

But “almost” is not enough.

Sean manipulates the situation. He’s better… until he isn’t. He uses the courts to control Alex.

She’s suddenly back at square one. No apartment. No college. No custody.

That’s her Dark Night of the Soul — not just losing her progress, but realising she must give up any illusion that Sean will ever change.

ACT IIIB: Climax and Resolution (Episodes 9–10).

Climax: Episode 9 “Sky Blue”.

Climax: Episode 9 “Sky Blue”.

Alex makes a bold, terrifying move: she files for sole custody. She calls Sean out.

She sees him clearly, for the first time — not as the father of her child, not as her former love, but as a threat.

And Sean — in a moment that surprised me (and probably you too) — lets her go. Not gracefully.

But honestly. It’s not redemption, but it’s real. And that’s what makes MAID so powerful: it never gives us neat bows. Just hard-won truth.

Resolution: Episode 10 “Snaps”.

Alex leaves. She gets into college. She hikes the M trail — literally climbs out of the valley of trauma.

It’s symbolic, and a little on-the-nose, but after everything she’s endured, we’ll take it.

It’s not happily ever after. But it’s forward.

Why This Matters for Writers.

As a writer, studying MAID was like taking a masterclass in structure and emotional storytelling.

It reminded me that:

TV is not just a longer movie. Each episode is its own arc. It needs to satisfy and hook.The 5-act structure isn’t just academic. It allows for layers, escalation, and multiple threads.

Three storylines keep a show dynamic. Audiences crave texture and complexity, not just one linear story.

And perhaps most importantly: Every scene has to do multiple things—develop character, advance plot, show theme, or create tone.

So yeah, writing a TV pilot is HARD. Writing a mini-series that spans ten episodes while honoring the 3-act movie structure? Even harder. But MAID pulls it off beautifully.

It’s a reminder that TV isn’t just the little sibling of cinema anymore. It’s a powerful form in its own right — where story structure, character arcs, and emotional truth come together in layered, surprising ways.

So the next time you sit down to write your own pilot, remember:

You’re not just telling one story.

You’re juggling three arcs per episode.

You’re playing a long game across a season.

And if you’re doing it right — you’re leaving your audience devastated and hopeful at the same time.

Just like MAID.

Now it’s YOUR turn – Would you tell this story differently? How?

Would love to get your input in the comment box below.

The post Breaking Down MAID – How MAID Nails TV Story Structure. appeared first on Vered Neta.

June 8, 2025

Crafting Killer Short Story Arcs.

The other day, I spotted a short story competition with a five-day deadline.

Naturally, my brain—ever the optimist—whispered, “Hey, why not turn that pilot episode of ‘Crime Cleaners’ into a short story?” Spoiler alert: my brain lied.

Because I forgot the cardinal rule of writing: the shorter the piece, the harder the punch.

Compressing a character arc, emotional payoff, and satisfying resolution into 3,000 words?

It’s like trying to fit a wedding dress, two cats, and a live saxophonist into a shoebox.

It can be done, sure, but there will be casualties. A misplaced veil. A disgruntled cat. A jazz solo in the key of regret.

So, what did I do instead of writing? Procrastinated, of course—with style.

I embarked on a valiant quest called “Research” that mostly involved reading excellent short stories while telling myself it was all part of the process. I never entered the competition.

But I did start a new monthly habit: writing one short story a month. Here’s what I learned from my noble rabbit-hole expedition.

#1 – Pressure Cooker: Start With Heat.

In short stories, there’s no time for leisurely introductions or meandering exposition. Drop your character into boiling water on page one.

That pressure—external or internal—forces the story forward and your character inward. The situation should be tense enough to demand action, even if that action is quiet or internal.

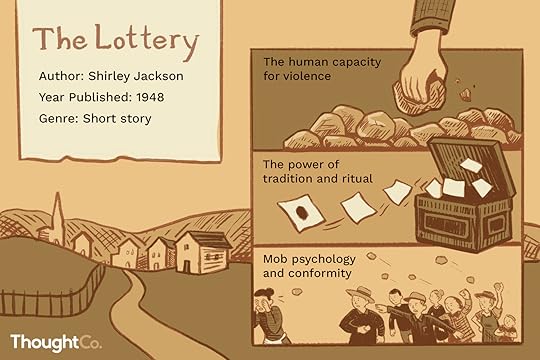

Think of Shirley Jackson’s “The Lottery.”

A small town gathers for an annual tradition. Kids are laughing. Adults are gossiping. But there’s a hum of unease. Enter Tessie Hutchinson, breezy and late, joking with the crowd.

But when the ritual’s true horror (ritualistic stoning, anyone?) surfaces, she screams, “It isn’t fair, it isn’t right!” In just a few pages, her belief in tradition gets eviscerated. Boom: arc delivered.

Short stories thrive on urgency. Whether that urgency comes from a ticking clock, a tense relationship, or the slow dawning of an existential crisis, the key is to light the fuse early. Let the flame catch.

#2 – Start With a Flawed Lens.

#2 – Start With a Flawed Lens.

Your character doesn’t need to be broken, but they should see the world through a slightly cracked lens.

That core belief—whether it’s “people are inherently good” or “if I’m not nice, I’ll die alone with cats”—is your starting line. The arc, then, is the slow (or sudden) shattering of that belief.

In Kristen Roupenian’s “Cat Person,” Margot believes being agreeable is safer than being honest. She goes on a date with Robert, ignores her gut instincts, and tries to keep things polite.

By the end, after enduring his emotional whiplash and receiving a jaw-dropping final text, she has a moment of hard-won clarity: maybe likeability isn’t worth her self-respect. It’s subtle, but you feel the shift.

A character’s flawed belief doesn’t have to be destructive. Sometimes it’s just outdated or incomplete. However, challenging that belief, especially under pressure, is where the story truly unfolds.

#3 – Cast Small, Hit Hard.

Short fiction isn’t the time for a sprawling ensemble cast. You need one or two well-drawn characters and maybe a barista for flavour.

Every supporting role should serve the main character’s journey—either by poking their flaw or nudging them toward change.

Take Hemingway’s “Hills Like White Elephants.” It’s just a man, a woman, and a drink while they wait for a train. They dance around the topic of abortion without saying the word.

The woman begins the story unsure and deferential. By the end, her silences have weight. Hemingway never shouts the arc—he whispers it, and it lands.

Every interaction in a short story should be meaningful. Even a single line from a side character can act as a turning point if it lands at the right moment.

#4 – Tiny Shifts, Titanic Ripples.

#4 – Tiny Shifts, Titanic Ripples.

A short story arc doesn’t need to end with your character moving to Bali and starting a kombucha empire.

Tiny shifts count. A new realisation. A decision they wouldn’t have made 10 pages ago. The smallest internal pivot can resonate deeply.

In Karen Russell’s “St. Lucy’s Home for Girls Raised by Wolves,” the narrator assimilates into human society, leaving her feral sister behind.

She doesn’t become a villain or a hero. She adapts. Survives. And realises what she’s lost. The change is small but devastating.

Think of it like this: if the story starts with the character looking through a foggy window, by the end, they may wipe just one corner clear. That’s enough. That’s movement.

#5 – Trust the Reader’s Brain.

Don’t spoon-feed. Short stories thrive on implication. Let your readers lean in, make connections, and fill in the emotional blanks. They’ll love you for it.

You’re building a collaborative emotional experience, and readers are smarter than we sometimes give them credit for.

Jhumpa Lahiri nails this in “A Temporary Matter.” A grieving couple reconnects during nightly blackouts. We hope, foolishly, that they’ll mend.

Then, one confession too far. The lights come on. And we just know: this is the end. Lahiri never needs to say it outright. She lets the silence do the heavy lifting.

Subtext is your best friend in a short story. Use it. Trust the reader to hear what’s not being said.

#6 – Objects Have Feelings Too.

When there’s no room for a character’s inner monologue, symbolism and setting step in like the understudies they are.

A favourite object, a shifting environment, a repeated image—these become the mirrors of internal change.

Ken Liu’s “The Paper Menagerie” breaks hearts using origami animals. Jack pushes away his Chinese heritage and his mother.

After her death, a note hidden inside a paper tiger reveals her sacrifices. The origami—once just paper—becomes sacred. Jack doesn’t need a monologue. His heartbreak speaks through the folded creatures.

If your character can’t say what they feel, show it in how they touch a scarf, how they linger in a childhood bedroom, how the weather changes as their perspective does. Make the world their diary.

#7 – Don’t Resolve. Resonate.

#7 – Don’t Resolve. Resonate.

Forget tidy bows. Forget big finales. The best short stories end like a haunting melody—lingering, not wrapping.

Leave your readers with an emotional echo, not a how-it-all-turned-out PowerPoint slide.

In George Saunders’ “Escape from Spiderhead,” a prisoner refuses to harm others, choosing death instead.

We don’t know what will happen next in the world. We just know he changed. He reclaimed his agency.

That’s what sticks. Not the facts. The feeling.

A short story’s power often lies in what it doesn’t say. Let your final paragraph be the emotional aftershock, not the cleanup crew.

In Short (Pun Intended…)So, what makes a character arc land in a short story? It’s not the size. It’s the sharpness.

Give us one crack in the surface, one ripple in the mirror. Make it matter.

Start with pressure. Give us a flawed belief. Keep the cast tight. Let change whisper.

Let silence speak. Let objects carry memory. And above all, don’t tie it up—let it ring.

If, by the end, your character sees themselves or their world just a little differently—if we, the readers, feel that difference in our bones—then you’ve done it. You’ve pulled off the literary equivalent of magic in miniature.

And if not? There’s always next month’s short story. Just don’t start with a 60-page pilot script, okay?

Or do. Just be prepared to share your shoebox with a saxophonist and two very annoyed cats.

Oh, and if you find a short story competition? Enter it. Not because you’ll win, but because you’ll write.

And writing—even with a jazz solo of regret in the background—is still the best part.

Now it’s YOUR turn –Which short story arc stuck with you?

Would love to get your input in the comment box below.

The post Crafting Killer Short Story Arcs. appeared first on Vered Neta.

June 1, 2025

Say Less, Mean More: Movie Subtext Moments.

Let’s be honest: life doesn’t come with a script, but if it did, a lot of it would be filled with things we don’t say. We sidestep the truth, swallow our feelings, or make jokes instead of confessions. And when film dialogue reflects that — when it allows characters to speak in subtext — magic happens.

Subtext is the silent engine behind great scenes. It’s how characters can lie while telling the truth, flirt while arguing, or apologize without ever saying “I’m sorry.” It’s the art of revealing emotional truths through implication rather than exposition — and when done well, it turns good writing into unforgettable storytelling.

Let’s explore how modern screenwriters are wielding this tool with seven brilliant examples each using a different flavor of subtext to draw us in.

7 Flavors of Subtext Every Screenwriter Should Study.

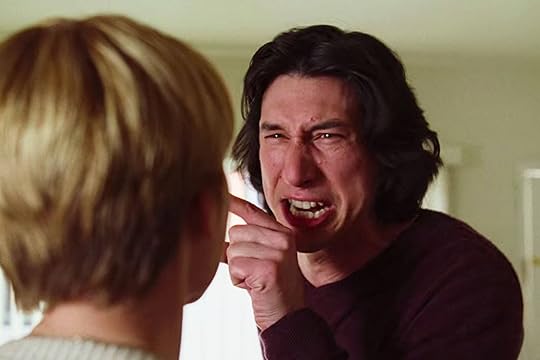

#1 – Marriage Story – Emotional Subtext via Conflict.

#1 – Marriage Story – Emotional Subtext via Conflict.

Let’s start with the most gut-wrenching fight scene in recent memory.

In Marriage Story, Nicole and Charlie’s apartment confrontation feels like two people hurling insults.

But underneath every cruel word is an aching desire to be understood — to be seen. The real story isn’t the divorce; it’s the slow death of connection and the desperate clinging to what remains.

What’s said:

“Every day I wake up and I hope you’re dead.”

What’s meant:

“I don’t want to hate you. But I can’t love you anymore, and that’s killing me.”

Why it works: The characters never state their real feelings directly. The anger masks grief, and the fight is the farewell. This is a masterclass in emotional subtext through conflict, where dialogue battles reveal inner wounds.

Blue Valentine also explores a deteriorating relationship, but it leans more into emotional avoidance rather than direct confrontation. While Marriage Story externalises pain through arguments, Blue Valentine buries it in silences, passive-aggressive moments, and scenes where characters almost say what they mean — but don’t.

#2 – Call Me By Your Name – Sexual Subtext and Vulnerability.

#2 – Call Me By Your Name – Sexual Subtext and Vulnerability.

In the peach scene (yes, that peach), Elio’s actions are shocking on the surface, but emotionally, he’s exposing his soul.

When Oliver enters and finds Elio ashamed and tearful, their interaction becomes wordlessly intimate.

Oliver’s gentle gesture of holding him speaks volumes.

What’s said:

“Why are you crying?”

What’s meant:

“I’ve never been this vulnerable with anyone. And I’m terrified you’ll leave.”

Why it works: The dialogue is sparse, but the silence between them throbs with longing and fear.

It’s sexual subtext mingled with emotional exposure — a moment where desire and connection become indistinguishable.

In Carol, physical intimacy is restrained by the era’s societal limitations, and subtext is conveyed through furtive glances and hesitations. Where Call Me By Your Name is emotionally raw, Carol is all about the slow burn — using delicate body language and unspoken yearning to convey intense feelings under the surface.

#3 – The Power of the Dog – Psychological Subtext through Objects.

Peter and Phil’s relationship is a psychological dance, brimming with intimidation, buried desire, and hidden agendas.

When Peter gives Phil a rope he braided from rawhide, it seems like a peace offering. But Phil soon falls ill, and we realise Peter used anthrax-laced material.

What’s said:

“I wanted you to have this.”

What’s meant:

“I’ve outsmarted you. And you never saw it coming.”

Why it works: The rope becomes the scene’s object of subtext — a seemingly benign gift that hides lethal intent. This is subtext as a chess match.

Gone Girl also uses objects — like Amy’s diary — as tools of manipulation, but the subtext is overtly performative. Where The Power of the Dog keeps you guessing about Peter’s true motives until the end,

Gone Girl lets the audience in on the deception, turning the subtext into a game of cat and mouse with the viewer.

#4 – Little Women – Feminist Subtext in Negotiation.

#4 – Little Women – Feminist Subtext in Negotiation.

Jo March’s negotiation with her publisher could easily have been dry. But instead, it’s layered with resistance, irony, and feminist commentary.

Jo “sells” her heroine into marriage only after making sure she profits from it.

What’s said:

“If I’m going to sell my heroine into marriage for money, I might as well get some of it.”

What’s meant:

“I know how the game is played — but I’m not playing it blind.”

Why it works: This is an ideological subtext wrapped in wit. The scene critiques publishing norms and gender roles without breaking character or tone.

While Jo negotiates her story’s ending within the bounds of a patriarchal system, Cassie in Promising Young Woman weaponises her femininity and silence to subvert those bounds entirely. Both use wit and control as subtextual armour — but one fights from within the system, the other dismantles it.

#5 – Barbie – Cultural Subtext Brought to the Surface.

For most of Barbie, the feminist message lives in the subtext — until Gloria (America Ferrera) delivers a monologue that cracks the whole thing open. It’s almost meta: the subtext becomes text because the characters can’t pretend anymore.

What’s said:

“It’s literally impossible to be a woman.”

What’s meant:

“We’ve all internalised a system that’s rigged against us — and it’s making us question our worth.”

Why it works: By holding back this truth for most of the film, the release of direct expression hits hard.

It’s an example of controlled subtext turned into catharsis.

Miranda Priestly in The Devil Wears Prada rarely raises her voice, but her words cut with surgical precision — the subtext lies in tone, timing, and what’s left unsaid.

Like Barbie, it reveals the high stakes of womanhood in a patriarchal world, only with couture instead of pink plastic.

#6 – Everything Everywhere All At Once – Emotional Subtext through Absurdity.

In the multiverse madness of Everything Everywhere All At Once, we get a moment of profound quiet: two rocks, perched on a cliff, having a conversation.

No faces. No actors. Just subtitles. And yet, it’s one of the most deeply human moments in recent film.

What’s said (as rocks):

“We’re all small and stupid.”

What’s meant:

“Despite the chaos, I still want to be here. With you.”

Why it works: Stripped of physical cues, the scene forces us to confront the existential subtext beneath everything — love, presence, absurdity, and meaning.

Inside Out also conveys the abstract into emotional resonance, especially in the memory dump scene with Bing Bong, where the subtext revolves around grief, memory, and letting go.

Like the rock scene in Everything Everywhere, it distils huge emotions into simple, unexpected visuals that carry profound weight.

#7 – Arrival – Philosophical Subtext through Language.

#7 – Arrival – Philosophical Subtext through Language.

When Louise (Amy Adams) realises that the alien language she’s decoding allows her to see time non-linearly, the entire film shifts.

Her flash-forwards — initially seen as memories — are her future with a child she knows she’ll lose.

What’s said:

“If you could see your whole life from start to finish, would you change things?”

What’s meant:

“Knowing the pain ahead… I would still choose love.”

Why it works: This is a philosophical and emotional subtext delivered through structure.

The screenplay doesn’t just say something profound — it functions as the message.

Her tackles love and loneliness through a futuristic lens, but where Arrival uses language as a metaphor for time and loss, Her uses technology to highlight the emotional gaps between people.

Both films offer deep philosophical subtext, questioning the cost of connection in a world that’s constantly evolving.

Subtext is what happens when your characters don’t say what they mean — because they can’t, or won’t, or don’t even know how to. It’s the tension beneath the dialogue, the meaning behind the look, the truth in the gesture.

To master subtext as a screenwriter, ask yourself:

What’s this character afraid to admit?What truth are they hiding — from others or themselves?Can I say it without saying it?Because the most powerful lines in cinema history are often the ones that are never spoken.

Happy writing!

Now it’s YOUR turn – Which recent character nailed the art of saying nothing—but meaning everything?

Would love to get your input in the comment box below.

The post Say Less, Mean More: Movie Subtext Moments. appeared first on Vered Neta.

May 25, 2025

Movie Night – Nonnas.

Directed: Stephen Chbosky.

Writer: Liz Maccie & Jody Scaravella.

Starring: Vince Vaughn, Lorraine Bracco, Brenda Vaccaro, Talia Shire & Susan Sarandon.

Trivia: The now closed world-famous restaurant in Elizabeth New Jersey, Spiritos, was used as the location of the restaurant.

****************************************************

Let’s be honest: sometimes, all you really want from a movie night is to be wrapped in a cinematic blanket of comfort. You want something that makes you laugh, sniffle a bit, and leave with a warm, satisfied smile—like finishing your Nonna’s lasagna and unbuttoning your jeans in blissful surrender.

Enter Nonnas, Netflix’s latest heartwarmer that knows exactly what it is—and, more importantly, what it’s not.

Yes, it’s got the shiny Netflix stamp.

Yes, it’s as predictable as a Hallmark Christmas movie.

And yes—I still enjoyed every single second of it.

What’s It About?Nonnas is inspired by the real-life story of Joe Scaravella, a Staten Island man who, in the wake of personal loss, opens a unique Italian restaurant with an unconventional staffing model—he hires grandmothers (or “nonnas”) from all over the world to cook the dishes of their homelands.

Why? Because Joe believes the heart of any meal is the person behind it. And who better to serve that kind of love than a grandmother who’s been cooking for decades and doesn’t care what you think about her portion sizes or cholesterol levels?

Vince Vaughn plays Joe. I’ll admit I braced myself for his usual “man-child in emotional denial” shtick. But surprise! He dials it down and brings a welcome tenderness to the role. For once, he’s not the sarcastic, emotionally stunted man-child we’ve come to expect. Instead, we meet him in a quiet moment of grief—he’s mourning his mother and a life that’s lost its meaning. But with the help of these unapologetically wise, loud, and loving women, Joe finds his way back to life, purpose, and maybe even joy.

What Worked.While Nonnas centres on Joe’s journey of healing, the true flavour and heart of the movie come from the four unforgettable women who bring life, drama, and delicious meals into his world. These aren’t your stereotypical sweet, apron-wearing grandmothers baking cookies and offering quiet wisdom. Oh no. These nonnas have sharp tongues, vivid pasts, and zero interest in playing by anyone’s rules—least of all Joe’s.

Lorraine Bracco plays Roberta, Joe’s late mother’s best friend. A proud Sicilian, Roberta now lives alone in a retirement home and is estranged from her children. She carries her loneliness like a secret ingredient she won’t admit to using—but it flavours everything she does. She’s tough and no-nonsense, but there’s a tenderness buried beneath her sarcasm that slowly simmers to the surface.

Then there’s Antonella from Bologna, portrayed with dry wit and restrained grief by Brenda Vaccaro. Fifteen years after the death of her beloved husband, she still speaks of him in the present tense. Antonella is prickly, opinionated, and—crucially—thinks Sicilian cooking is overrated. Her disdain for Roberta’s culinary heritage sparks some of the movie’s best squabbles and most heartfelt reconciliations.

Talia Shire’s Teresa is perhaps the quietest of the group, but her story lingers. A nun who has recently left the convent, Teresa is grappling with what it means to live a life without structure, vows, or habit. Her only true love, we learn, was another woman—also a nun—making Teresa’s backstory a poignant commentary on sacrifice and repression. She brings a gentle stillness to the chaos around her, but don’t mistake her serenity for weakness. She’s strong in ways the others only begin to see.

And then, sweeping in with a complete blowout and bold lipstick, is Susan Sarandon as Gia—a flamboyant, fiercely independent nonna who never married, never needed to, and proudly runs her own hair salon. Gia believes beauty is ageless and that women should celebrate themselves at every stage of life. She brings sparkle, sass, and a shot of Prosecco energy to the ensemble. Gia is the embodiment of self-love and living out loud, and Sarandon plays her with just the right blend of camp and conviction.

Together, these four women bring not just flavour to Joe’s restaurant, but soul. They challenge him, each other, and the very idea of what ageing “gracefully” is supposed to look like. And while their pasta might be perfect, it’s their imperfections—the grief, the regrets, the secrets—that make them irresistible.

The movie doesn’t try to be edgy or original. It’s not here to shock or provoke. Instead, it wants you to feel—to remember your own grandmother’s kitchen, your own memories of family meals and old stories—and it does that beautifully.

What Didn’t.Let’s not kid ourselves: Nonnas doesn’t break any storytelling moulds.

Yes, you will guess every major plot point before it happens.

Yes, there’s a conflict with a corrupt health inspector.

Yes, Joe ends up drowning in debt and nearly has to sell the restaurant.

Yes, his best friend, who believed in him enough to help fund the place, sells his beloved classic car just to keep things afloat.

And yes, there’s a desperate third-act Hail Mary where Joe tries to attract some press attention by visiting a famous food blogger… only to be completely humiliated.

But here’s the thing: predictability isn’t the same as failure. In fact, Nonnas uses its formulaic structure to its advantage. Much like comfort food, you want to know what you’re getting.

The pleasure comes not from surprise, but from the execution—and here, that execution is filled with warmth, humour, and just enough spice to keep things interesting.

While the Nonnas are the clear highlight, we don’t get quite enough depth into their backstories. There are hints—Teresa’s heartbreak, Antonella’s grief, Roberta’s loneliness, Gia’s fierce independence—but they’re lightly touched on and then left behind. We want more time with them, more insight into what shaped these women beyond their delicious gnocchi and zingers. Their chemistry is gold; the script just doesn’t dig deep enough to mine all of it.

Finally, if you’re expecting a groundbreaking story or a fresh take on the “found family heals broken man through food” trope… well, this isn’t that dish. It’s comfort food cinema, and it stays firmly within its flavour profile. And for some, that might feel a little under-seasoned.

Final Thoughts.Nonnas is cinematic comfort food. It’s not fancy, not revolutionary—but it’s full of flavour, heart, and charm. Sometimes, especially in these overwhelming times, that’s more than enough. There’s something so refreshing about a film that doesn’t pretend to be more than it is—and something deeply satisfying about watching a group of older women steal the spotlight, one ladle at a time.

So if you’re in the mood for something heartwarming, low-stakes, and generously seasoned with love, pull up a chair at Nonnas. You’ll laugh, you might tear up, and you’ll probably crave pasta by the end.

Just don’t call it sauce. It’s gravy.

VERDICT – 3.5/5 Stars in my Book.

The post Movie Night – Nonnas. appeared first on Vered Neta.

May 18, 2025

The Stage Lives of Stories We Love.

Last week, my daughter came to visit, and—as tends to happen when two opinionated creatives share a cup of coffee and a love of drama—we dove headfirst into a lively debate.

She’s a stage manager who lives and breathes theatre, and I’m a writer dipping my toes into both novels and scripts. Naturally, the conversation got… animated. (Okay, okay—spirited. Passionate. Let’s just say the cats left the room halfway through.)

We found ourselves unravelling the unique beasts that are writing for novels, screen, and stage.

And let me tell you—those are three very different creatures, each with its own habits, quirks, and appetite for storytelling.

But when the laughter settled and the theatrical hand-gesturing stopped, I had a lightbulb moment.

Before you even think about adapting a novel (or screenplay) for the theatre, you need to understand the journey that the story has to take. Because it’s not just a switch in format—it’s a full-blown metamorphosis.

There’s something downright magical about watching a story leap off the static page or the polished screen and come to life in front of a live audience. Theatre isn’t just a new container—it’s a whole new ecosystem.

Adapting stories for the stage is a bit like cooking without a recipe but still making a five-course meal.

You need to trust your instincts, adjust the seasoning, and know when to let the ingredients shine.

But how exactly does that transformation happen? Why do some stories blossom on stage while others fizzle? And what makes adapting for theatre so different from making a film sequel or TV reboot?

Let’s lift the curtain and take a peek behind the scenes. You’ll want a front-row seat for this one.

Why Adapt a Story for Theatre?At first glance, adapting a beloved novel or film for the theatre might seem like a limitation.

After all, there’s no CGI, no sweeping location shots, and no ability to quietly “zoom in” on a character’s thoughts with a voice-over. But therein lies the magic of theatre: it thrives on constraints.

Theatre is immediate and intimate. It invites the audience to imagine the castle, the battlefield, or the time machine rather than showing it in 4K.

In return, theatre gives us something no other medium can: the visceral, real-time connection between actor and audience.

A good adaptation doesn’t just retell a story—it reinterprets it. It discovers what makes the heart of the story beat and then asks: How do we make that pulse on stage?

Step One: Choosing the Right Story.

Not every story is a good candidate for theatrical adaptation. A great theatrical story typically includes:

Strong characters whose inner journeys can be externalised through dialogue and action.Emotional or philosophical depth that can resonate through metaphor and stagecraft.

Tension and conflict that can sustain dramatic momentum, even without elaborate visuals.

A compact or flexible setting (or a way to abstract it) that works within stage limitations

That’s why character-driven stories with rich subtext often make the most compelling adaptations.

Let’s have a look at the adaptation of The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time.

Mark Haddon’s novel was told entirely from the perspective of a teenage boy with autism, complete with internal monologues and visual metaphors. It hardly screamed “stage-ready.”

Yet the National Theatre’s 2012 adaptation used lighting, physical theatre, and minimalistic staging to show Christopher’s unique perception of the world.

The result? A theatrical experience that was emotionally raw, visually inventive, and wildly successful.

Step Two: The Art of Transformation.

Step Two: The Art of Transformation.

An adaptation is not a transcription. You can’t just lift a chapter from a book or a scene from a film and paste it into a script.

You must find the theatrical equivalent of the story moment.

Where a novel might spend five pages inside a character’s head, theatre must express that emotion through:

DialoguePhysical action

Visual metaphor

Symbolic staging

Choreography or music

A great example for this is – War Horse.

Michael Morpurgo’s novel is told through the eyes of a horse during World War I. Spielberg turned it into a sweeping film with battlefield panoramas and emotional close-ups. But the theatrical version, created by the National Theatre, did something remarkable: it used life-sized puppets. Yes, puppets.

The physical presence of these creatures, manipulated by skilled puppeteers in full view of the audience, made the story even more poignant. The audience wasn’t being tricked into thinking the horses were real—they were invited to believe in them.

The result? Standing ovations, global tours, and tears in audiences who didn’t expect to cry over wood and fabric.

Step Three: Dialogue and Stage Directions.

Once you’ve decided how to theatricalise the story, it’s time to write the script. This is where things can get tricky.

Novel to stage: You must invent dialogue where there was once only narration. That means giving characters voices, rhythms, and vocabulary that feel true to the source while serving the pacing and demands of live performance.Film to stage: Here, you often trim dialogue, stripping scenes to their emotional core, and rethink pacing since live actors can’t rely on editing or visual montages.

A fine example of the issue of dialogue is the stage adaptation of To Kill a Mockingbird.

Harper Lee’s classic novel is dense with narrative and inner thought. Aaron Sorkin’s 2018 Broadway adaptation had to strip the story down to its essentials while injecting new urgency and energy into the dialogue.

Using his incredible skill of dialogue writing and court drama (let’s never forget that A Few Good Men was first a play by him), he centred the play more around the trial, restructuring the narrative to build dramatic tension while preserving the soul of Atticus Finch’s moral struggle. Some purists scorned it, but theatre-goers were gripped.

Step Four: Visual Imagination on a Budget.

Unlike films, where money can buy realism, the theatre often relies on metaphor.

This is where the creative team—set designers, lighting artists, costume designers, choreographers—becomes as essential as the playwright.

A single table can become a kitchen, a courtroom, or a spaceship. A spotlight and sound effect can simulate an explosion.

And sometimes, less is more.

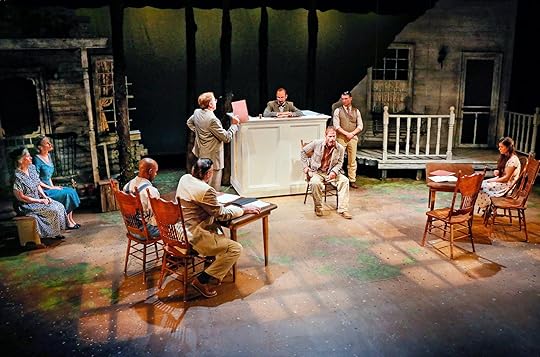

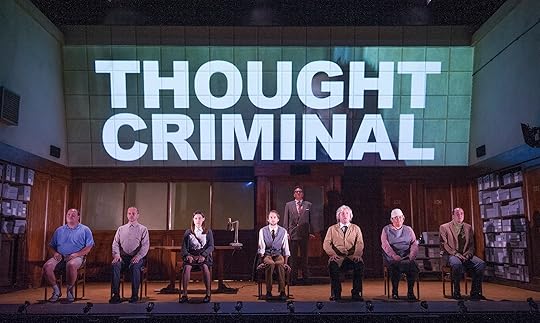

An excellent example of it is the stage version of 1984.

George Orwell’s dystopian masterpiece is notoriously bleak and internal.

However, the stage version (adapted by Robert Icke and Duncan Macmillan) used stark lighting, jarring sound design, and chillingly clinical sets to evoke the oppressive world of Big Brother. It didn’t show every detail—it suggested just enough to let the audience’s own fear fill in the blanks.

Step Five: Rehearsals and Discovery.

The rehearsal process is where everything is tested and rewritten. What worked on the page might feel flat on stage.

Some lines will be cut, and some characters may be combined. Blocking (stage movement) reveals what scenes feel static.

Actors bring their own interpretations, often surfacing emotional layers the writer didn’t consciously intend.

Adaptation is a living, breathing collaboration.

A favourite example of mine for this is the stage musical Once.

The 2007 indie film Once was quiet, intimate, and filmed on the streets of Dublin.

The stage musical adaptation had to keep that intimacy, so the cast doubled as the orchestra. Musicians moved in and out of scenes, blending live music with naturalistic storytelling.

The result? A Tony Award-winning production that kept the heart of the original but became something uniquely theatrical.

Step Six: The Power of Reinvention.

What’s beautiful about theatrical adaptations is that they rarely aim to be faithful in the literal sense.

Instead, they aim to be truthful to the essence of the story.

Theatre has the power to reveal new angles in familiar tales. Sometimes, it even fixes flaws.

In my opinion, one of the best examples of it is A Monster Calls.

Patrick Ness’s bestselling novel, illustrated by Jim Kay and conceived initially by Siobhan Dowd, is deeply internal—a grief-stricken boy, a dying mother, and a monstrous yew tree that visits him in the night to tell unsettling stories.

The novel weaves fantasy, memory, and raw emotion with subtlety. But it became something extraordinary when the Old Vic brought it to the stage in 2018 (directed by Sally Cookson).

Using ropes, movement, soundscapes, and ensemble physical theatre, the stage adaptation captured the emotional storms within Conor’s head.

The monster wasn’t a towering animatronic or a masked villain—actors and metaphor embodied it.

The result was a heartbreakingly honest depiction of grief, memory, and childhood resilience.

It didn’t recreate the novel—it amplified it.

Final Curtain: Why It Matters.

Adapting a story for theatre isn’t just about putting something familiar in a new format.

It’s about discovering why this story matters now, and how live performance can make us feel it more deeply.

At its best, adaptation is transformation. It’s not about imitation—it’s about interpretation.

And it’s one of the most thrilling, collaborative, and challenging forms of storytelling out there.

So the next time you sit in a velvet seat and the lights dim, remember: the story you’re about to see may have started on the page or screen, but the stage is where it comes alive.

Now it’s YOUR turn – What’s the best stage adaptation you’ve ever seen?

Would love to get your input in the comment box below.

The post The Stage Lives of Stories We Love. appeared first on Vered Neta.

May 11, 2025

Feminism in Pop Culture Movies.

Feminism is back in the headlines—again.

In late 2023, the UK Supreme Court ruled that legal recognition of gender doesn’t override biological sex in certain contexts (like women-only spaces).

For some, it was a defense of sex-based rights. For others, a gut-punch to the trans community.

And once again, we found ourselves deep in that very 2020s question:

Who gets to be called a woman—and what are feminists fighting for these days anyway?

Spoiler alert: there’s no one answer. Feminism is no longer a single movement (if it ever was).

Today, we’ve got radical feminism, liberal feminism, ecofeminism, intersectional feminism, trans-inclusive feminism, and even “I’m-not-a-feminist-but-I-like-equal-pay” feminism.

And like every good sequel, the discourse is messier, more emotionally charged, and full of plot twists.

So where can we go to make sense of all this?

Strangely enough, the best place might be the movies.

Specifically: genre fiction.

Yep. Sci-fi, horror, fantasy, and superhero flicks might seem like escapist fun (and they are), but they’re also cultural pressure cookers—testing ideas about identity, freedom, power, and yes… womanhood.

Think of genre stories as feminism’s wild younger cousin: less polite, more dramatic, and often holding up a mirror when we least expect it.

#1 – The Hunger Games.

Before we had warrior Barbie or multiverse Evelyns, we had Katniss.

Bow-wielding, braid-rocking, PR-reluctant Katniss Everdeen—maybe the most iconic feminist figure of the 2010s.

But here’s the twist: Katniss never wanted to lead a revolution. She didn’t volunteer because she was empowered—she did it to save her sister.

She didn’t rebel to break the system—she did it because the system broke her.

Her story isn’t about becoming a girlboss; it’s about the emotional cost of being turned into a symbol.

This is feminism through the lens of class struggle, trauma, and reluctant leadership.

It’s about how female bodies are turned into propaganda—whether for the Capitol’s entertainment or the Resistance’s revolution.

Is Katniss a feminist icon? Yes.

Is she comfortable with that label? Not remotely.

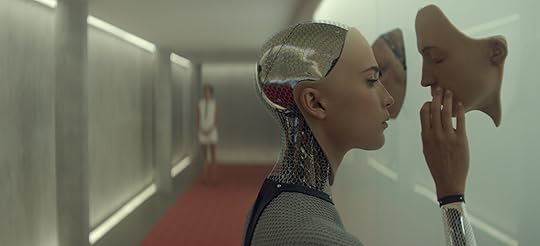

#2 – Ex Machina.

#2 – Ex Machina.

Now for something darker.

Imagine a tech billionaire building his dream woman in a bunker. Sounds like Elon Musk’s fantasy, right?

That’s Ex Machina. But don’t be fooled—this is no robot love story.

Ava, the AI, is designed to be beautiful, seductive, and obedient. She’s built to pass the Turing Test, but really, she’s just trying to survive a world created by men who want to use her. (Relatable.)

Her escape isn’t just a sci-fi plot twist—it’s a metaphor for what it means to be seen as female before being understood as human. Ava manipulates the men around her because it’s the only power she has—and in doing so, she flips the script on every “perfect girlfriend” trope we’ve ever absorbed.

It’s creepy, chilling, and wickedly smart. Just like some of the best feminist commentary.

#3 – Wonder Woman.

We waited decades for a female-led superhero movie that wasn’t just… bad.

And Wonder Woman delivered—with a sword, a shield, and the most badass slo-mo No Man’s Land scene of all time.

But Diana isn’t just muscle and myth.

She’s also tender, idealistic, and yes—romantic. She believes in love as a world-saving force.

That softness was a radical choice in a genre where women often have to become emotionally armored to be taken seriously.

Of course, Wonder Woman sparked debates too. Is it feminist if she’s running around in a miniskirt?

Does her perfect beauty undermine her message? Is it enough to show “strong women,” or do we also need flawed, complicated ones?

The answer is: yes. All of the above. Feminism can wield a sword and believe in love. Diana would approve.

#4 – The Witch.

Cue the goat. In Robert Eggers’ The Witch,

a Puritan family banishes their teenage daughter Thomasin after a series of spooky misfortunes.

But instead of apologizing for her (possibly) witchy ways, she leans in—hard.

This isn’t your sparkly witch kind of film. It’s gritty, slow, and quietly horrifying. But it’s also a feminist origin story in disguise.

Thomasin is punished for her body, her voice, and her very existence. When she finally says, “Screw it,” and joins the coven, it’s not just a plot twist—it’s liberation.

Radical feminists have long seen witches as the original scapegoats of patriarchy: women who refused to be controlled. The Witch doesn’t just agree—it lights the fire, dances naked around it, and whispers, “Wouldst thou like to live deliciously?”

Honestly? Who wouldn’t.

#5 – Barbie.

Yes, I’m counting Barbie as genre fiction—because what else would you call a movie where dolls enter the Real World to confront patriarchy, toxic masculinity, and their own plastic existential dread?

Greta Gerwig’s Barbie is campy, colourful, and laugh-out-loud funny—but also deeply layered.

It tackles feminism 101 (equal rights), 201 (internalised misogyny), and postgrad stuff (what does it mean to be a woman when every version of womanhood is contradictory?).

Margot Robbie’s Barbie is a woman in crisis: too much, not enough, never quite right. Sound familiar?

And then there’s Ken. Oh Ken. His “Mojo Dojo Casa House” arc shows how easily patriarchy recruits even the most harmless-seeming guys when they feel left out.

It’s a feminist comedy that punches up, then hugs you after.

#6 – Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse.

You may be thinking: Wait—Spider-Man? Really?

But Across the Spider-Verse isn’t just about Miles Morales; it’s also Gwen Stacy’s movie. And Gwen’s story is rich with metaphor.

She’s part of a “canon” that says her life must follow certain tragic rules. She must lose someone. She must stay on the sidelines.