Bill Hiatt's Blog, page 3

May 9, 2019

The Problems of Teaching Biblical Literature

(copyrighted by Rick Becker-Leckrone and licensed from www.shutterstock.com)

The Dilemma of Teaching the Bible as Literature

Influence of the Bible on Western Society

If you’re an English teacher, you probably already know most of what is mentioned here, but it’s possible some new teachers might not have given the issue much thought.

Actually, the issue doesn’t just relate to English teachers. Biblical literature (and religion in general) is pretty difficult to avoid in the teaching of history and the arts. Even though not every Westerner is a member of a Biblically-based religion, Western society has been influenced by the Bible in many ways.

I’m most familiar with the literary influences. The Bible underlies earlier English writers like Chaucer, Shakespeare, and Milton (the Big Three back when I was taking English classes at UCLA in the mid 1970s), and pretty much any other Western writer prior to the modern era. However, its influence is still visible in more contemporary works by Steinbeck, Faulkner, Hemingway, Golding, Atwood, O’Connor, and many others. Even contemporary bestsellers like J.K. Rowling and Stephen King make use of Biblical elements. ( see this article and this article ) for some interesting examples.

Michelangelo’s David (image copyrighted by PrakichTreetasayuth and licensed from www.shutterstock.com)

However, literature is only part of the picture. I was reminded of this frequently while I was teaching. For instance, some of my Jewish students who were taking AP Art History would complain about the endless (from their point of view) procession of Christian images they were studying. Even with the course’s recent inclusion of much more study of non-Western art, the enormous amount of religious imagery in the Western part is hard to miss. Music is just as much affected as the visual arts. I got a reminder of that every year as December neared. Someone almost always questioned the number of Christmas songs in the holiday music concert. The long-time vocal music teacher, who was Jewish–a cantor and the son of a prominent local rabbi–had to keep pointing out that the bulk of the most challenging seasonal music was Christian in origin. He didn’t mention the Bible specifically, but in fact the vast majority of the Christmas songs were explicitly Biblically based.

The Prevalence of Biblical Illiteracy

Prominent as the Biblical influence in our culture is, I was always surprised at how many students struggled with material that required knowledge of the Bible. I taught two classes that included some Biblical literature: Freshman Honors English, and World Literature and Composition. For most of my career, I taught at least one of those classes, and sometimes both, so I had a lot of opportunity to observe how little Biblical knowledge students brought to the class.

(copyrighted by Sabphoto and licensed from www.shutterstock.com)

For example, in Freshman Honors, we used an anthology that included Biblical texts and parallels in later literature. One of the sections features passages from Genesis and Mark Twain’s Adam’s Diary. You would be amazed at the number of students who couldn’t distinguish between the two. I still remember a student asking how Genesis could possibly have a reference to Niagra Falls in it. Eventually, we had to drop Zora Neale Hurston’s Moses, Man of the Mountain from summer reading because students couldn’t distinguish what Hurston said about Moses from what the Bible said about him.

Nor did the seniors in World Literature do any better. More than once, I got questions about why Santa Claus wasn’t in the Christmas story–from students who really weren’t kidding, much as I wish they were. The classic example, though, came from an essay written at the end of The Epic of Gilgamesh unit. One of the topics I used had to do with the differing attitudes toward heroism between ancient Sumerian society and our own. Many years ago, I received an essay on that topic that started this way: “Every society has its heroes. For example, Hinduism has Buddha, and Jewism has Jesus.” If one wanted to be nitpicky, that doesn’t directly misrepresent the Bible per se, but it’s hard to imagine that someone who can’t distinguish between Christianity and Judaism (or even name them correctly) has much Biblical knowledge.

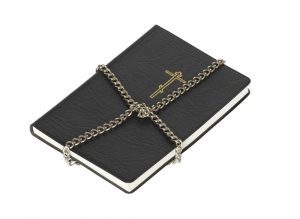

Possible Controversy over Teaching the Bible

Since Western cultural literacy demands some knowledge of the Bible, and since most students seem to have very little of that knowledge, some study of the Bible as literature is essential. Public schools have the obligation not to advocate any particular religious philosophy, so in English classes, we’re obviously teaching the Bible as literature, not as a religious text. However, that distinction isn’t always easy to make, particularly with teenagers. Even some adults have difficulty figuring out what the difference really is. At best, handling the material requires a delicate balancing act on the part of the teacher, as I’ll explain below.

(copyrighted by cosma and licensed from www.shutterstock.com)

I worked in a high school in a relatively liberal community, so the curriculum was seldom challenged. In fact, I just glanced at a list of the eleven most commonly banned books ( found here ), and five of the eleven are or have been part of the curriculum in at least one course, all without protest. In the longer list of forty-six challenged books from the Radcliff Publishing Course Top 100 Novels of the Twentieth Century ( found here ), I counted twenty-two that are or have been part of the regular curriculum, as well as an additional eleven that are commonly on reading lists for book reports–again, all without challenge.

What one book did get challenged during my thirty-four years at the same school? The Bible. Generally, the reasons weren’t anti-religious. Parents objected not because they felt all religious literature should be banned, but because they were not Christian and had a problem with part of the New Testament being taught. However, atheists have from time to time mounted challenges against all religious literature, so you could encounter that as well. Students often objected too, but the motivation was more often avoiding something they feared might be boring. Typically, I’d start with several students objecting, but it didn’t take long to win them over.

Strategies To Teach the Bible as Literature without Having Issues

Explain what you are doing clearly, concisely, and early.

I always started a Biblical unit with an explanation of both why Biblical literacy was important and how teaching the Bible could be made consistent with constitutional requirements. (You may not get challenged directly on legality, but having worked in a district in which a large number of the parents were lawyers and a large number of students wanted to be, I found it useful to cover all the bases. It’s better to be prepared, just in case.)

The first handout focuses on the value of Biblical literature, the second on legal issues. I used both for years, so these are rather old and not especially good examples of graphic design. At the bottom of this post, you can download the Word originals if you want to rework them. That may also be useful for the legal one, which is California-centric. It would be better for you to provide case law and opinions relevant to your own state.

FH Use of Religious Literature

BIBLLIT

Make sure your own knowledge is as complete as possible.

(copyrighted by Stokkete and licensed from www.shutterstock.com)

Good preparation is important for teaching any subject, but it’s especially important in handling Biblical literature. Despite the fact that many students will be Biblically illiterate, some of them can and will ask relatively obscure questions. It’s not a problem if you can’t immediately answer a question. Offering to find the information or encouraging students to research it themselves and report back aren’t bad strategies. It is a problem, though, if you give inaccurate information. Knowing how adolescents are, you know someone will correct you later on. That will make students who are already nervous about the subject matter more nervous.

Manage discussion carefully.

Class discussion is an area in which studying the Bible as literature can really go off the rails in a big way. While students generally don’t start proselytizing for their own point of view, it’s not uncommon for some of them to declare whatever they believe to be the only possible interpretation.

Normally, of course, students getting excited about their opinion of literature is exactly what you want, and the more animated the discussion gets, the better. That atmosphere can be a problem for Biblical discussions, though.

The key, as in so many other situations, is balance. I never had a problem with student briefly stating their own religious beliefs as long as they prefaced them with “I believe” or some similar statement and do not imply that everyone should believe as they do. I also made it clear to students that they couldn’t ridicule a religious perspective different from their own or even argue with someone else’s.

To set the right tone, it’s important to lead by example. I wouldn’t normally hesitate to give my own interpretation of literature, but in Biblical discussions I typically respond to interpretive questions with, “Some people believe that…, other people believe this,” and so on. This is another point where knowing what you are talking about is important. You don’t want to misstate the view held by a particular religious group if you can help it. Ideally, every English teacher who taught the Bible as literature would be well versed in the study of comparative religions. No one can be knowledgeable about every possible variation, but it helps to know the major ones.

(copyrighted by Syda Productions and licensed from www.shutterstock.com)

Near of the beginning of the Biblical unit, I always talk about some of the major variations in the ways in which the Biblical text can be interpreted. It’s important to realize that some groups believe in full verbal divine inspiration–that is, that every word has been divinely inspired and is normally to be interpreted as literally as possible. Others believe that the Bible contains divine inspiration but that all parts may not be equally divinely inspired. Others (Universalists, for example) believe that the Bible and many other religious texts contain divinely inspired truths. Still others believe that the Bible is divine inspiration conveyed in ways that the original audience could understand; the general ideas are true, but the details, particularly with regard to science and history, may be concessions to what the original audience could understand and accept. Then there are those who see the Bible as divinely inspired but not literally true on factual matters. In this view, the stories are symbolic or allegorical, rather than literal. At the opposite end of the spectrum from full verbal divine inspiration would be people in non-Biblical religious traditions, who would regard the text as containing no inspiration at all.

You might expect some knowledge of the vast differences of opinion to be common knowledge, but that’s another area high school students have a problem with. To illustrate that point, I sometimes used a chart showing that even on such a simple question as what books were in the Bible, there were wide differences of opinion. As with the earlier documents, if you’d like to adapt this material, I’ve included the Word copy as a download at the end of this post.

(copyrighted by B Stefanov and licensed from www.shutterstock.com)

To see how a variety of interpretations would play out in practice, let’s look at the story of the serpent in the Garden of Eden, for example. Taking the text at face value, the serpent is a serpent, and the story is partly an explanation of why serpents have no legs, though that obviously isn’t its main point. Later interpreters, however, saw a variety of different truths in it. Christian commentators almost universally see the serpent as either symbolic of Satan or literally Satan. Medieval Kabbalistic Jewish commentators sometimes saw the serpent as Lilith (Adam’s first wife in the Talmud). Gnostics in early Christianity inverted the story by making the serpent the hero of the story, the one who brings knowledge to Adam and Eve that the creator (in Gnostic thinking an inferior being who was not the true God) had tried to keep from them. Roman Catholic thinkers saw the eating of the forbidden fruit that the serpent helped to engineer as the origin of original sin, but some of them also referred to it as felix culpa (fortunate fault) because it was a necessary step in the spiritual development of the human race. That’s just some of the more prominent beliefs associated with the story. One could write a book about it, and I’m sure people have.

I wouldn’t bring up every possible variation, of course, but I would try to make sure the students understood that there were different ways to look at the story. I would also try to ensure balance in the discussion. If one view seemed to be predominating, I would be sure to mention a different one. That way, a quiet student who didn’t necessarily agree with the majority would still feel safe in believing something else.

That’s really the heart of a good discussion on the Bible as literature. Everyone can voice his or her view–or not voice it. Either way, the classroom is a safe space to hold that view. If you create that kind of atmosphere, you should have minimal problems with the unit.

Word Downloads

(If you just want the PDF format, you can download that directly from the viewer windows above.)

Legal Issues

Download Now!

Value

Download Now!

Contents

Download Now!

(A form of this article was published on October 31, 2017.)

The Problems of Teaching Greek Mythology

Sanctuary of Athena at Delphi (licensed from www.shutterstock.com and copyrighted by peterlazzarino)

Why Is It Important to teach Greek Mythology?

This section is primarily for those of you who aren’t English teachers, though there is some difference of opinion on this subject, even among English teachers.

I’m a big believer in avoiding what Will Herberg referred to as a “cut flower culture.” That’s true, not just in the spiritual sense in which Herberg meant it. It’s also true in the sense of general knowledge. If we don’t understand the roots of our culture, we don’t really understand our culture.

In Western civilizations, the Bible is the most influential literature hands-down. I’ll talk more about that in a subsequent blog post, but I will mention quickly that I don’t intend that as a religious statement. One can have the cultural literacy that the Bible provides without being an adherent of a Biblically based religion. (As I used to say to my students, you can read Moby Dick without having to believe that there was a great white whale that matched the title beast’s description.)

It’s hard to miss the classical columns and other touches in early American public architecture. You can see the classical influence on the University of Virginia rotunda, designed by Thomas Jefferson. (Joseph Sohm/Shutterstock.com)

Though the Bible in indisputably the single most influential body of literature in the West, Graeco-Roman literature is just as securely number two. Our own literature, film visual arts, music, law, philosophy, and even architecture are all indebted to the Greeks and Romans.

From the moment that the United States declared its independence, it tried to establish its own cultural identity. While not rejecting its English heritage, it turned to Greece and Rome, sometimes directly and sometimes indirectly, for political inspiration. Democracy comes originally from a Greek word, just as republic comes from a Latin one and evokes the Roman Republic. We also borrowed Senate from the Romans, among other things.

Shakespeare is a good example of a writer strongly influenced by the Graeco-Roman heritage. Two of his favorite works were Ovid’s Metamorphoses and Plutarch’s Lives. (If you’re interested in details, Jonathan Bate’s Soul of the Age: a Biography of the Mind of William Shakespeare provides a very thorough treatment of Shakespeare’s use of the classical heritage. I can’t at the moment find any commentaries more narrowly focused on sources that aren’t very expensive.) The story of Pyramus and Thisbe crops up twice in his work, once as the distant ancestor of the plot of Romeo and Juliet, and once directly, in Midsummer Night’s Dream. His Roman history plays are naturally based on Plutarch. His longer poems, Venus and Adonis and The Rape of Lucrece , are similarly classically inspired. Some of his early comedies seem based on Roman models. His tragedies, much like those of his contemporaries, owe something to the tragedies of Seneca. Even in plays like The Tempest, that are less obviously connected, still show Graeco-Roman touches. For instance, Bate notes the similarities between the way Prospero’s magic is described and the way Medea’s dark arts are portrayed in Ovid.

Nor is Shakespeare the only author inspired by the Graeco-Roman tradition. Even a very partial list seems overwhelming: Chaucer, Dante, Ariosto, Milton, Shelley, Keats, Tennyson, Pope, Shaw, Joyce, Hawthorne, T.S. Eliot, Eugene O’Neill, Thornton Wilder, John Updike, and too many others to list here. I should mention that the influence continues even today. Consider Rick Riordan’s Percy Jackson books, for example.

My more pragmatic students used to say, “So what?” The specific answer in an English classroom would be that it’s hard to understand classically inspired literature without some knowledge of that heritage. The same thing is true in college. A survey by the Society of Biblical Literature, which naturally focused on the importance of biblical literacy, did ask one question about Greek and Roman literature, and the professors surveyed agreed that knowledge of Greek and Roman mythology gave students a clear academic advantage. Since students typically need to take at least a few English classes to satisfy breadth requirements, even the most narrowly grade-oriented students would have to agree that a certain amount of classical knowledge would be helpful in college.

Unfortunately, teaching Greek and Roman literature, mythology in particular, does raise some problems.

Pediment at Academy of Athens (copyrighted by Anastasios71 and licensed from www.shutterstock.com)

What Are the Problems of Teaching Greek Mythology?

First, despite how much the ancient Greeks and Romans contributed to our own society, the cultural gap between the two sometimes seems overwhelming. As with most ancient societies, women were generally considered a form of property, slavery was accepted without question, violence was a much more popular solution to problems–and the list goes on. It’s hard not to be offended or disturbed by at least some of it. On the other hand, denaturing it too far to make it more palatable to contemporary high school students takes away some of its educational value. Also, students need to be able to understand other cultures, even when they don’t agree with the values of those cultures. Finding the right balance is tough, though.

Second, because the mythology comes to us through the writings of dozens of authors over a span of centuries, the stories are often inconsistent. One can often find contradictions even within the same author’s work. (Hesiod describes Cronus as imprisoned in Tartarus in one work but says that he is ruling Elysium in another.) It is this incoherence that frustrates students who can lead the hurdle of cultural difference to appreciate science fiction and fantasy. That’s because a modern novel, TV show or movie in one of those genres will have a consistency mythology lacks.

(copyrighted by sabphoto and licensed from www.shutterstock.com)

Real people and believable literary characters act somewhat predictably. If their attitudes and actions change, they do so ways that seem motivated by changing circumstances. In the case of literary characters, that’s why readers can relate to them. That’s also why it’s hard for teenagers to relate to characters who don’t stay consistent from story to story. Is Heracles a great hero, a well-meaning oaf, or a murdering sociopath? Is Aphrodite the gentle patroness of love who takes pity on Pygmalion by bringing the statue he has fallen in love with to life, the harsh punisher who gets Hippolytus falsely accused of rape so that his own father will kill him, or the nightmare prospective mother-in-law in the Cupid and Psyche story? Is Lycomedes the paranoid who murders Theseus on the off-chance that the hero might one day take his throne or the easily duped father who somehow accepts Achilles having sex with one of his daughters after being given sanctuary in his home? Sometimes logical reasons can be found for these apparent contradictions, but often they can’t be reconciled. They simply are. Sure, some of the variants can be tossed out, but too much sculpting of the material will remove some of its value in the same way that too much cultural adaptation will. Again, it’s tough to find a good balance.

During the several years that I taught a freshman honors English class in which mythology was an important component, I spent quite a bit of time searching for a good mythology book. At the time, we were using Edith Hamilton’s Mythology. It’s unquestionably a classic, and adult mythology enthusiasts still love it, but it was never intended for teenagers, and a lot of contemporary teenagers have trouble with it.

Replacing it, however, was easier said than done. I searched for years, and the books I could find fell into three categories. First were the adaptation intended for children. As a young child, I loved D’Aulaires Book of Greek Myths, and I’d still recommend it to someone looking for a book for young readers, but it’s a little too young for high school.

(copyrighted by Sabphoto and licensed from www.shutterstock.com)

The second group were the works intended for scholarly use, such as The Routledge Handbook of Greek Mythology and the more literary but still scholarly Greek Myths by Robert Graves. Both are too long and too complex for high school and are not well-adapted to a teenage audience, though either would be great for comprehensive adult study.

The third group are books for the general reader that primarily address one myth or connected group of myths. Any of those might work for high school, but none of them has a wide enough range to cover even the same ground that Edith Hamilton does.

I even offered my students extra credit to anyone who could find a mythology book that met my criteria. No one ever could, though.

After I retired, I learned that the teachers who followed me in freshman honors were having the same problems with mythology I had experienced. I still hadn’t found a workable alternative, so, in collaboration with my former colleagues, I decided on a radical experiment: I would write my own mythology book.

Shameless Plug for My Book

(copyrighted by Slava Gerj and licensed from www.shutterstock.com)

My book, A Dream Come True: An Entertaining Way for Students To Learn Greek Mythology, adopts a different approach than a typical mythology text, in part because of its hybrid nature. The myths are wrapped in a young adult urban fantasy frame story. The basic premise is that some high school students cramming for a mythology fall asleep, and when they wake up, they find themselves in the world of Greek mythology. At first, they have no idea how to get back to the real world. Even worse, one of them gets on Hera’s bad side, ends up becoming a dog and then vanishing before Hera can undo what she has done. Complicating matters still further is that the remaining students unwittingly become entangled in a plot by god or gods unknown to disrupt the order of Olympus.

They cling to the idea that they are just dreaming–but what about the old superstition that if you die in a dream, you die in real life? And what happens if they can’t find their missing friend? Saving him and escaping require them to unravel the mystery of who the secret rebel among the gods really is. In the process of looking for clues, the students have to travel throughout ancient Greece (both real and mythical) and examine each myth (often told by one or more of the characters in the myth).

What benefits does this approach provide?

(copyrighted by Slava Gerj and licensed from www.shutterstock.com)

High school students seem to react better to the novel format than a series of short tales. They’re just more used to it. It’s also worth noting that the frame story itself is an ancient technique, the oldest surviving example of which is Ovid’s Metamorphoses.

By having the student characters raise the same questions that students used to have in class, the book addresses potential points of confusion as they arise. It also enables the student characters to frame the stories in terms of modern values. Thus, though individual stories may not agree with a reader’s moral sense, the book as a whole provides more comfortable and familiar messages without whitewashing the original material. It also offers opportunities for philosophical discussion and debate among the characters. That leaves room to show some differences–ancient Greek society was not monolithic. It also leaves room for modern differences of opinion. Every single issue raised by the myths is not one we’d all answer in the same way, and I didn’t want the book to be overly preachy or to push too hard in one direction on controversial issues. At the same time, it does provide some opportunities to include character education in the study of mythology.

Fleshing out the mythological characters as if they were real people, in particular providing them with consistent personas, makes it easier for students to relate to them. How did I do that without denaturing the material? Naturally, I had to pick a version of each story, and usually I picked the ones that could most easily fit together. However, I preserved major variations by having the characters discuss them as rumors or as deliberate propaganda by their enemies. By the way, there’s a good argument, made by Graves among others, that some of the stories were intended as political propaganda originally. For example, the more savage stories about Heracles may come from the time after the Dorian invasion. At that point the other Greek peoples had every reason to try to discredit Heracles because the Dorian leaders claimed descent from him. It’s easy to see in other cases how one Greek city would try to build up its own hero while a rival city might try to tear him down. The same thing may be true of the gods, whose major centers of worship were often in conflict with each other.

The presence of the student characters makes it easier to make the text interdisciplinary. I’ve already mentioned character education, but you’ll also find bits of history, psychology, art and architecture as well.

[image error]

(copyrighted by Sabphoto and licensed from www.shutterstock.com)

I think the book strikes the right balance between preserving the integrity of the original material and adapting it to a modern high school audience. Whenever possible, I resolved conflicts (and potentially inappropriate material) using an approach found in the works of at least one ancient writer. Points where I had to go beyond the literature are clearly identified, often in the text itself, always in an appendix.

Speaking of appendices, there are several. They are intended to meet the needs of different students. Some will need help sorting out the complicated family relationships, and for them I provided a wealth of genealogies. Some will be content with the text alone, but others may want further resources, and for them I provided an extensive annotated list. I also provided the ancient sources for the material in each chapter. (Students need plenty of reinforcement in citing sources, but extensive in-text source citations are distracting to some high school readers.) For the benefit of teachers who want to be sure students also know the Roman names, I’ve included an appendix for those as well.

Results of the Book’s First Use

The two teachers using the book in their freshman honors English classes both reported higher levels of engagement and better test results than with the book they had been using previously. I came in as a guest speaker when they were prepping for the test and noticed more enthusiasm for the subject matter than I had seen when I taught the class. That’s not to say that every single student was thrilled by the book, but it does seem to work better than some alternatives.

Handy Book Preview If You Want to Find Out More:

Information for Schools Considering Adoption:

I’m happy to answer any questions you may have. Please feel free to email me at the address in the header for further information.

I intended this book to be a service rather than a moneymaker. (Given its hybrid nature, it’s not destined to be a bestseller.)

Teacher Stress Management

(copyrighted by KieferPix and licensed from Shutterstock)

One of the most surprising things about teaching I discovered when I first started in the profession was how much stress a teaching job generates. Nowadays I think teacher training programs incorporate more material about that, but even with some preparation, it’s difficult to really understand the levels of stress involved until one actually teaches.

The second surprise is that students are often not the primary cause of teacher stress. Sure, we’ve all had the mischievous soul who tried our patience or the student in trouble who tugged our heart strings a little too hard, but in my experience much more stress can come from outside factors such as inadequate funding or excessive politicization, as well as adults in the system who somehow find ways to make your life more difficult.

Why should you be concerned about stress? Because too much stress reduces the effectiveness of your teaching. I won’t repeat all the evidence for that here, since it is amply documented elsewhere, but if you are interested in specifics, you might want to look at articles like this (though it focuses more on depression, one of the possible consequences of stress), this, and this.

Searching the links above reminded me what part of the problem is. Even with searches carefully tailored to elicit results about teacher stress, most of the top hits were articles about student stress. Don’t get me wrong–student stress is also very important. However, a lot of analyses have a tendency to forget that teachers are people, too, and that their psychological state can also be important.

Not only is stress destructive in the classroom, but it’s toxic to your health as well. You can find a good summary of those issues here. I didn’t really become aware of the variety and seriousness of the problems until my former school district stated having trouble with insurance providers. They frequently cited stress-related health problems as a reason to charge more for group insurance, and that naturally got me thinking about the subject.

In the interest of full disclosure, I never succeeded in mastering my stress; it’s why I retired early. I apparently got out just in time, too. I was starting to develop some very obvious stress-related symptoms, like having chronic low-level headaches that stopped every summer.

That said, my experience with handling stress and seeing how other people handled it might be useful to you, so I have provided some tips below.

Organize yourself well. That was always hard for me, but I definitely felt less stress when I had more control. In practice that meant not having to hunt for things, not getting two meeting scheduled at the same time, that kind of thing. The time organization takes is more than made up for by the time–and frustration–you save down the line.

Set manageable goals each day, and, except in unforeseen circumstances, meet those goals. I don’t know why, but I used to go into a day sometimes thinking I would get far more grading done than I did. When I failed to meet my goal–which happened often with overly ambitious grading goals–I ended up feeling more stress. I’ve seen students fall into the same pattern, and in either case the result is likely to be a downward spiral, since rising stress levels will make it harder to meet the next goal down the line.

Make time for relaxation and enjoyment. Some of you, particularly English teachers or others in high-paperload disciplines will laugh about this one, but it’s true. You cannot work all the time without running the risk of overly high stress levels, and eventually, burnout. Part of having a good organization is making time in your plan for pleasurable activities.

(copyrighted by Monkey Business Images and licensed from Shutterstock)

Make time for family and friends. Don’t forget about the people in your life, no matter how much work you have. It’s easy to lose track of old friends and even create tensions within the family by not keeping in touch. When I first started teaching high school, I couldn’t help noticing how many of my colleagues in the English department were either divorced or unmarried. In fact, one of the standard jokes among the younger teachers was that the official card game of the English department was Old Maid. Ironically, I ended up unmarried as well, and over time my friends outside of school faded away. You may think this is an avoidable problem, and it is, but it is also very easy to keep putting off the people in your life until a more convenient time–which sometimes takes weeks to arrive.

Take advantage of every little opportunity for exercise. Unless you teach physical education, there may not be much built-in exercise in your job, and though teaching itself isn’t that sedentary, grading and planning both are. Even if you don’t have time for a regular workout at the gym, you can still increase the exercise you get–and lower your stress in the process–by finding ways to insert short bursts of exercise into your daily routine. For example, I worked in a multistory building and always took the stairs instead of the elevator. When I could run errands on foot rather than by car, I did that (which also saved me the stress of traffic and finding a parking place). Some schools will help by organizing teachers for before and/or after school fitness walks or something similar. Make use of any opportunity like that if it fits your schedule.

Realize that you can’t do everything. One of the biggest stress creators in teaching is the fact that it is in many ways a bottomless-pit job. No matter how much you’re doing, you can always be doing more. Because of that, it’s easy for teachers to overwork themselves, as well as to be overworked by the system. Realizing one’s limits is hard; I got there only near the end of my career. Hopefully, you’ll be better. The key is figuring out how much you can reasonably do for your students, and, except in cases of dire emergency, resist the urge to keep escalating. For instance, if you’re an English teacher, you have to learn not to give massive amounts of feedback on each essay. Perhaps a few key assignments will need that much. Others can get less, or get feedback focused only on one aspect. Others may get a check-off rubric rather than comments. If you train your students well enough, peer feedback can also supplement the feedback you give. If a student is really struggling, you can also vary the amount of feedback you give on each assignment based on student need–but in that case, monitor yourself carefully to make sure your feedback is not creeping beyond a manageable level.

(copyrighted by PKpix and licensed from Shutterstock)

Yes, all of these suggestions are common sense. Unfortunately, it’s all too easy to lose track of common sense in the maelstrom that is teaching.

(A form of this article was published on October 30, 2016.)

What’s the Purpose of Education?

(copyrighted by Monkey Business Images and licensed from www.shutterstock.com)

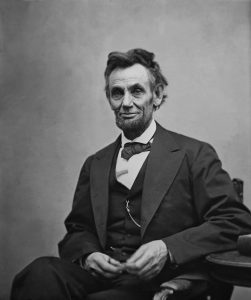

“The function of education is to teach one to think intensively and to think critically. But education which stops with efficiency may prove the greatest menace to society. The most dangerous criminal may be the man gifted with reason but no morals.…We must remember that intelligence is not enough. Intelligence plus character—that is the goal of true education.”

Martin Luther King, Jr., Morehouse College speech, 1948

One crucial step in creating the best possible education system is figuring out what you want that system to accomplish. While establishing goals sounds as if it should be simple, the process isn’t as easy as one might think.

(copyrighted by digidreamgrafix and licensed from www.shutterstock.com)

A recent Phi Beta Kappa poll illustrates the problem: 45% of people surveyed said the primary purpose of the school system should be to prepare students academically, 26% said it should be to prepare students to be good citizens, and 25% said it should be to prepare students for work. The US News and World Report article on the poll describes the current state of the issue as “confusion.” Indeed, if we can all agree on one thing, it’s that people find defining the purpose of education confusing.

In part these poll results may suggest a reaction against the one-size-for-all college-for-everyone ideal that schools (and education reformers) have embraced in recent decades. My former school district, which has always had graduates go on to college at a rate above 90%, a few years ago eliminated all courses that weren’t “college prep,” (by which school board members really meant UC certified–all courses had been designed with college in mind).

(copyrighted by Elnur and licensed from www.shutterstock.com)

As much as a rigid tracking system (in which at some point students are locked into a particular path from which they have a hard time escaping) is bad, it’s interesting that people often miss the fact that the kind of system my former district adopted is essentially a rigid tracking system with only one track: college. While we all agree that every student should have the opportunity to go to college, is it really true that is the best choice for every single one of them, without exception? For example, if a student really wants to be an auto mechanic, is there a reason to force four years of college–and a load of student debt–on him or her?

(image copyrighted by goodluz and licensed from www.shutterstock.com)

It isn’t just students who are involved in “hands-on” professions like auto repair who might not always be a good fit for college. That’s the theory behind Peter Thiel’s idea of paying students to develop their own business ideas rather than go to college. One of my former students set up his own resale business that grossed $30,000 a year while he was still in high school. He went to college to get a business degree, but I could see someone wanting to spend those four years growing a business that was already successful. I’ve also known students who had flourishing acting careers when they were still in high school. Several ending up getting their diplomas through the high school equivalency exam. Some of those did end up getting college degrees, usually in a nontraditional way, but it would be hard to argue, unless they went to a performing arts school, that a college degree had much to do with their actual careers.

(copyrighted by kwest and licensed from www.shutterstock.com)

I should mention that, among the courses eliminated by my former district were all those offerings geared to students reading two or more grade levels below the norm. Students in that situation could get into community college but probably wouldn’t have the grades to get into a four-year school immediately after high school. Could a student like that improve his or her reading level enough to perform decently in college? The research I’ve seen suggests the answer is yes–if he or she had the very kind of support structure the board cut away in its zeal for UC certified courses. Yes, you’re reading that correctly: in order to push every student to college, the district removed the very structure the weakest students would have needed to have a shot at making that goal.

(copyrighted by Dennis Kuvaev and licensed from www.shutterstock.com)

By the way, even with the right kind of support, such a student would probably not improve more than 1.5 years in reading level for every year in school. If you do the math, that means someone coming into 9th grade reading at the 6th grade level would catch up with his or her peers at the earliest by sophomore year in college. That kind of situation might be another reason for a student to attend a community college, which often provide remedial programs for students with skill deficits.

Not only did the district never quite grasp this reality, but it also tended to sneer at community college as a possible option. Board discussions often made it seem as if community college really wasn’t college at all, often cited college attendance statistics that counted only graduates who went to four-year schools, and otherwise disparaged any suggestion that community colleges were worth anyone’s time–an especially odd position considering the number of career paths that require only an associate’s degree for entry. Rather than accept the fact that some students’ performance in high school might make community college the best next step, the district told counselors to make lists of four-year schools that would take students with B averages and C averages. (I didn’t stay long enough to see the inevitable D average list, but I’m pretty sure the South Harmon Institute of Technology would have been at the top of it.) There was even talk of making applying to a four-year school a graduation requirement, though in that case the total unenforceability of that idea defeated it.

(copyrighted by pelfophoto and licensed from www.shutterstock.com)

If you’ve been around long enough, you realize that when the pendulum swings too far in one direction, it tends to swing back too far in the other direction. The inevitable reaction of trying to shove everyone into college, regardless of circumstances, naturally bred pressure in the other direction. The mounting college debt crisis didn’t help the situation, either. Peter Thiel was not alone in trying to promote noncollege pathways.

Despite what I wrote earlier, too much of a pendulum swing in that direction would be a profound mistake.

(copyrighted by llike and licensed from www.shutterstock.com)

While I don’t believe that every single student’s first-best destiny involves college, I do believe in choices. Students should be prepared for college, even if that sometimes means having the support of more basic classes they might need to get them to the right level, and even if a few of them ultimately decide on a different path. To do otherwise would be foolhardy. Though we can cite individual exceptions, a Pew Research report in 2014 confirms that college graduates make far more than their high school graduate peers–and that gap is widening. The same report confirms that the college graduates are considerably less likely to be unemployed or to be living in poverty, as well as more likely to be satisfied with their jobs and confident in their ability to advance further in their chosen career.

Nor should the short-term employment picture be our only consideration. Yes, some people are successful without college, and some people earn degrees that don’t lead to a career in any logical way. Again, however, those are exceptional cases–and training narrowly for one job doesn’t do justice to the rapidly changing realities of the job market. The Hechinger Report points out that a well-designed college education can develop general critical thinking and creativity that may help prepare students for jobs of the future that don’t even exist yet, among other things.

(image copyrighted by Lightspring and licensed from www.shutterstock.com)

You’ll notice that the poll results with which the article started present us with a false trichotomy, at least to some extent. The implied split between academic preparation and job preparation isn’t as sharp a divide as one might at first assume, except for people for whom vocational school might arguably be a better option. Even students whose college major doesn’t directly prepare for a career may be preparing for work–and life–in ways that may not be immediately apparent. Yes, we should make sure that vocational pathways are available, as Katherine Martinko has argued, but that can be done in the context of a high school model that embraces preparing students to make choices rather than pushes them in only one direction. (The student who wants to be a mechanic today may change his mind tomorrow and needs to have the skills to shift paths if he or she wants. In any case, the way we are going will probably require mechanics to also have considerable computer skills before very much longer.)

(copyrighted by Rawpixel and licensed from www.shutterstock.com)

What about citizenship preparation? It is possible to integrate that with academic and career preparation in a way that does justice to all three. English, of course, lends itself to just such a synthesis, since literary analysis flows naturally into discussion of the moral and philosophical issues raised in the literature, but English is certainly not the only discipline that does that. History teaches citizenship through the mistakes and triumphs of the past, government by making sure everyone was a working knowledge of the political process, and virtually every discipline contributes in some way, because an effective voter is a well-informed voter. (Unlike Donald Trump, I don’t love poorly educated voters!) For example, someone with a working knowledge of biology is better able to understand the moral and practical implications of genetic research. Someone with a working knowledge of economics is in a much better position to evaluate the merits of different financial proposals.

Yes, my perspective is idealistic. In an era of diminishing school resources, it’s hard for the schools to do justice to everything with which they are asked to cope. However, if we decide that developing the intellect, the career and the citizenship are all equally important, we can make it happen. Prioritizing goals that all have such great importance is not an option.

(copyrighted by Marvent and licensed from www.shutterstock.com)

Tips for Students Who Want To Start a New School Year Right

(copyrighted by RyFlip and licensed from www.shutterstock.com)

(This article is written with high school students in mind, though in some cases the advice might also work for younger students.)

When it’s that time of year again, hopefully you’ll look forward to with joy–but realistically you may end up missing the summer, at least for awhile. If you’re reading this article, you probably know that school, whether you view it as a thrill or a chore, is important to you. Making the most of education now can make life a lot more rewarding in the future. With that in mind, I’ve compiled some suggestions for how to make the most of that opportunity.

Make a good impression on your teachers.

You know the old saying, “You never have a second chance to make a first impression”? There is a lot of truth to it. I’m not suggesting that you should adopt a “teacher’s pet” mentality. I am suggesting that common courtesy goes a long way in human relationships in general, and student-teacher relationships are no exception. Since it is possible to be polite without being a “kiss-up,” make every effort to treat your teachers well. Remember that teachers are people too. (I know it sounds silly to say that. Of course you know teachers are people, but I’ve found that high school students don’t always embrace that truth emotionally. Early in my teaching career, I ran into some some students at the UCLA Mardi Gras, and one of them said, “Mr. Hiatt, what are you doing here?” I replied, “Probably the same thing you are,” and they all looked stunned, as if they were thinking, “You mean you don’t crawl into the filing cabinet at the end of the school day and go into suspended animation until school starts again?” I would have thought of this experience as a one-off kind of thing, except that it happened a lot.)

(copyrighted by s-ts and licensed from www.shutterstock.com)

Aside from being polite to the teacher, if you have negative feelings about the subject matter, try to keep those to yourself. Strange as it may seem, teachers would like to think that, even if everyone isn’t thrilled by the subjects they teach, everyone understands that those subjects are important. Teachers know that not everyone is going to be naturally brilliant in their subject and that levels of enthusiasm will vary, but, especially early in the year, it’s best to avoid questions like, “When will we ever use this in real life?”

It is also wise to avoid rookie mistakes. These include sitting as far back in the room as you can (which suggests that you are trying to hide–and therefore that you will probably want to get away with something), showing negative feelings toward other students (since teachers don’t like bullies and might misinterpret your intent), and being overly informal with the teacher (since teachers, though they should be friendly, can’t actually be your friends). That last point seems paradoxical to some students, but if you think about it, you’ll realize it’s true. That said, teachers do accept varying levels of formality. As the year progresses, you’ll get a more specific feeling of what is and is not appropriate in each classroom. At the beginning of the year, it’s best to be relatively formal. You can always loosen up later, if the teacher’s style allows for it.

(Special Note for Juniors)

If you are planning on applying to colleges that require teacher recommendations, then you may already know that your junior teachers (particularly the ones in academic subjects) will probably be the ones from whom you need to select recommenders.

As with any other kind of sales pitch, recommendations are much easier to write when the teacher is advocating for a student about which he or she is enthusiastic. It’s in your best interest not only to make a good first impression, but to maintain that first impression throughout the year. I’m not suggesting that you be phony to do that, but I am suggesting that, as the University of California system recommended to students writing college application essays, “Be yourself, but be your best self.”

Take it from someone who’s written recommendations for over a thousand students during my teaching career. If you create the best record you can, a teacher will have no difficulty writing for you, even if you aren’t the world’s most brilliant student. If you do less than your best, a teacher will generally know it, and, while he or she won’t make overt negative statements about you, college admissions people reading those letters are good at spotting situations in which the teacher is faking it rather than being genuinely enthusiastic.

Be as active a participant as you can.

(copyrighted by michaeljung and licensed from www.shutterstock.com)

All things being equal, actively engaged students learn more than passive ones. Not only that, but, to return to my last point for just a minute, a teacher is more likely to know an active student better than a passive one. Remember that recommendation writers have to comment on your personal qualities as well as your academic achievements–and I can tell you from experience a teacher isn’t going to have a clear picture of a student’s personality if the teacher has never even heard the person’s voice.

Some of you may be cringing at this point if you’re shy. You don’t have to become Mr. or Ms. Assertive overnight. Remember that teachers also value improvement. If you have weak spots but are trying to improve, a teacher will understand that and appreciate your effort.

What that means in practical terms is that you should try to participate a little bit at first and gradually work yourself up to more. The students I’ve known who made the attempt were always happy they had. The students who didn’t were just postponing the inevitable in some cases. The reality is that a lot of professions involve a certain amount of verbal interaction, so if you want to go into some of those fields, you will have to take the plunge sooner or later.

By the way, if you’re prepping for an oral presentation and want some pointers, you can find the video version of my PowerPoint on the subject here.

(copyrighted by Rawpixel.com and licensed from www.shutterstock.com)

Get organized–and stay that way.

If you have a typical load, you probably have five or six classes, and some of you may have more. That’s going to be a lot of instructions, handouts, and deadlines coming at you, so good organization is essential.

Some schools have partially automated the process in one or more ways: assignment calendars posted online, email assignment reminders, and other similar devices. However, many have not, so you need some way, whether digital or nondigital, for keeping track. If a school or teacher doesn’t limit your options (for example, by banning digital devices in the classroom), find a system that work well for you. If you are constrained by rules from using the system you like best, find the best way to work within the structure you have.

Ask questions–unless you can answer them yourself.

(copyrighted by Lorraine Swanson and licensed from www.shutterstock.com)

Asking questions is an important part of learning, and no good teacher is ever going to be annoyed by a legitimate question. That said, teachers can be annoyed–and you can end up wasting their time and yours–by asking a question for which you could very easily have figured out the answer yourself.

The classic example of this kind of problem is the student who has been given written directions and asks a question that could easily have been answered just by reading those directions. Chances are you’ll never again get as many written directions as you do in high school, so why not take advantage of them? Always read the directions first. Then ask the question if you still need to.

The same advice also applies to oral directions. Listen to what the teacher is saying, and then ask if you still need to.

It also pays to listen to the questions other people ask–and the answers they get. I can’t tell you how many times I got asked the same question I’d already answered in the same class session. No one is perfect, of course, so you may miss an earlier questions occasionally, but doing it often suggests you aren’t paying attention–and that creates a whole new set of problems.

(copyrighted by Monkey Business images and licensed from www.shutterstock.com)

Take notes.

Every year I was amazed by the number of students not taking notes or taking notes so vague that they would have been useless for review.

In the thirty-four years I taught, I encountered very few students with such good memories that they could perform as well without taking notes as they could with notes. My own experiment in two senior classes showed that note-taking students performed 19% better than non-note-takers in one class and over 25% better than non-notetakers in the other one. These results are not surprising, since studies have shown anything from a 13% gain to a 44% gain from note-taking. With that kind of evidence, it’s surprising everyone doesn’t take notes by choice. Sadly, many of my students had to be forced, and then they often did the bare minimum.

How you take notes is largely a matter of personal preference, unless your teacher mandates a particular style. My personal preference for some time has been digital notes (easier to search and organize, less likely to be lost). There is a lot of research suggesting that digital notes are not as effective, however. One of those studies is reported here. Looking at the reasons digital note-taking is less effective, though, I think their impact could be reduced or eliminated. Basically, the students in the studies that looked at this issue either wrote too much (and therefore stopped listening as well) or became distracted by the digital environment in one way or another. Oddly enough, in several years of encouraging students to take notes digitally, I never saw a student doing the transcript style note-taking criticized in the study. In any case, it seems to me that a person could train himself or herself not to write too much down. The digital distraction issue is a more serious one, and it often causes both high school teachers and college professors to ban laptops, tablets, and cell phones in their classes. I always felt that students needed to learn how to overcome those distractions, but I’ll admit it wasn’t an easy thing for some students to do. If you are in an environment in which digital note-taking is permissible, you’ll need to train yourself to avoid the temptations that format presents.

Even if you take physical notes, you still need to adopt a reasonable strategy in order for them to be effective. That means you need to practice identifying the material that is the most important (and/or that you’re the most likely to forget). You also need to write it down in a way that captures enough to remind you of what you heard, but not so much that you get bogged down in the physical process.

If you haven’t thought much about note-taking at all, you might like this summary of different methods. That doesn’t mean you can’t develop your own system, as some of you probably have. Just make sure it works for you.

Below is the notetaking handout I used to distribute to students. It provides a fuller explanation and might prove useful to some of you. If you need help with the viewer controls, there are some tips here. (The viewer seems to be having some trouble with Chrome at the moment, so just in case, I’ve also included a download button.

Class Notes 2014

If you have control over the membership of a work group, think carefully.

Group? Yes. Work? Doubtful! (copyrighted by Belushi and licensed from www.shutterstock.com)

Most of you have probably had some experience with group work, since it plays a role in a number of different instructional strategies. More often than not, the teacher will select the group membership, but if you are given some discretion, make good use of it.

The first problem I’ve noticed in student-selected groups is the tendency for people to group with their friends. This kind of arrangement naturally leads to a variety of temptations you would ideally want to avoid–at least if you actually want to get work done.

Even in situations in which friends in a group managed to avoid too much socializing, I sometimes found the group didn’t work as well as it should because the students shared common weaknesses. For example, it doesn’t make sense if you’re shy to group with all of your shy friends to plan an oral presentation.

The ideal group is one in which everyone gets along, but either is not composed of friends or includes only friends who can resist temptation. In addition, every skill required by the task is covered by at least one student. The ideal group also has one person who is accepted as leader (organizer) and who has the skills to keep the group on task. If the group has to do some work outside of class, it’s also important that the members have compatible schedules (a variable I noticed students often forgot to check).

Understand the basics of plagiarism.

(copyrighted by Jacek Dudzinski and licensed from www.shutterstock.com)

I know this point seems hyperspecific when compared to some of the other pieces of advice, but in my experience that was one of the areas in which students most commonly got themselves into trouble.

Most of students I saw shoot themselves in the foot on this issue erred in the same way: they copied homework (and yes, that’s plagiarism), and then they claimed they “just worked together on it.” Remember that homework is always individual unless a teacher or professor specifies otherwise. Also remember that, if an assignment is collaborative, the names of all collaborators must be listed on it.

Another common error was forgetting that anything derived from a source (for example, an image) needed to be cited. When I had a class working in a computer lab on presentations, I was shocked by how often students grabbed images without even thinking about the need to acknowledge their source, and I often spent a good part of the period nagging them to remember that point.

Sadly, I also had one or two cases per year of students who engaged in much more blatant plagiarism, like borrowing part or all of a sibling’s or friend’s essay. That is one of the most effective ways to destroy your own grade quickly and completely.

Rather than repeating everything I told students about plagiarism, I have embedded my plagiarism handout below.

Plagiarism Guidelines 2014

Also, you can find my possibly entertaining but definitely informative plagiarism video here. In addition, this video has a nice review of what needs to be cited. Both videos have a table of contents, so you click pretty easily to the part you want.

Work hard, but not harder than you can endure.

(copyrighted by wavebreakermedia and licensed from www.shutterstock.com)

I know that statement sounds strange, but being a successful student involves striking a balance. Particularly if you are taking challenging classes, you will probably need to work hard, and those of you who have a passion for something and/or want to get into a highly selective college may be spending hours on some extracurricular program (or maybe even more than one).

The problem is that there are only so many hours in the day, and everyone needs not only a decent amount of sleep but some downtime in order to recharge effectively. When students take on more than they can handle, the result can be decline in academic performance, damage to one’s health, or perhaps even both. I have known students who developed ulcers or had nervous breakdowns. I’ve known others who started out loving school as freshmen and ended up hating it by the time they were seniors. Sometimes such students were driven by their parents into situations they couldn’t handle, but often they drove themselves into an impossible position.

Remember that it doesn’t do you any good to get admitted to your dream college and be unable to attend because your health is too poor to handle it. It also doesn’t do you any good to get in if you have burned yourself out and won’t be able to perform at college. I put the idea in those terms because striving to get into a top college is one of the primary factors pushing students into overextending themselves.

Some people can handle what it takes to get into Harvard. If you can’t really handle it, this is not one of those situations in which it’s noble to die trying. It’s better to lead a happy and healthy life and go to a college with somewhat less demanding admissions standards.

Some people don’t learn that truth until it’s too late. Please don’t be one of those people.

(A form of this article was published on August 16, 2016.)

Practicing Publishing on the Internet–Without Actually Publishing

(copyrighted by Sabphoto and licensed from www.shutterstock.com)

In my previous post, which you can read here, I talked a little bit about the dilemmas of high school student online publishing. According to the Common Core (and, let’s face it, common sense), students need to have some practice in creating and publishing documents online. They need to be able to use more than just text, including multimedia, and, even if they can’t code an entire page, they should probably have a rough understanding of what HTML is and how it works, because, even with the increasing emphasis on building entire sites without coding, there are times when it’s nice to be able to tinker. It’s also good if they can figure out how to adapt the environment in which they’re working to the needs of the particular project.

The issue is complicated by the fact that most students, at least in my experience, don’t have some or all of the basic skills they would need for anything more elaborate than classic word processing. They probably know how to post a status update on Facebook and perform other social media tasks, and they might well be able to handle a heavily templated environment, such as exists on Wix or Weebly, but take away the training wheels, and many of them would hit the ground with a resounding crash.

A Possible Solution: Self-Hosted WordPress

In the previous post, I’ve already discussed a few free ways to facilitate the process by giving students a work space and a place to “publish” without actually going public (and raising administrative concerns). It’s also possible your school has an LMS (Learning Management System) that provides an appropriate digital workspace for students. In this post I’d like to talk about what I’d suggest to a teacher who doesn’t have such an LMS but does have a little bit of a budget and an administration willing to support the idea: self-hosted WordPress.

Why WordPress? Because it’s a very popular content management system for everything from one-person blogs to corporate websites. If the students are going to learn a content management system, they may as well learn the one they are most likely to use later on. The statistics speak for themselves. For the week of August 1, 2016, for example, WordPress accounted for 51% of all CMS (Content Management System) usage, Joomla! for 7%, Blogger and Drupal for 2% each, all others at no more than 1% each. Looking at the United States alone (and for some odd reason only at sites using the .com extension), various WordPress versions accounted for 52%, various Wix versions for 13%, Joomla! and Squarespace for 3% each, and GoDaddy Website Builder for 2%. (You can find all the statistics here.)

Why self-hosted? Because the free sites on WordPress.com won’t give you and your students as much flexibility. In particular, you can’t install plugins on a WordPress.com site, and the suggestion I am going to make requires them. A self-hosted WordPress installation also allows you to show students more about how to configure and use such a site. This kind of information is not just for webmasters, web designers, or bloggers anymore. Though it is true that large businesses will probably have a dedicated division for running their website or use third-party website management, small businesses are very likely to handle their own web presence, increasing the number of people who need at least some knowledge of what’s going on under the hood.

Resources Needed for Implementation

(copyrighted by Timofeev Vladimir and licensed from www.shutterstock.com)

You do need to have a little budget to make this idea work. I checked with the two web-hosting companies with which I am familiar, GoDaddy and Bluehost, and in both cases the least expensive plans, economy and basic, respectively, have an introductory price of $3.99 per month, reverting eventually to $7.99 per month. If you have some kind of supply or other budget, or a supportive PTA that provides some funding, and a receptive administration, that’s not an impossible price to meet. With ample storage (50 GB on BlueHost or 100 on GoDaddy), it’s possible for several teachers to share that space, making the cost per student relatively low. Having more than one teacher involved could also make funding easier, particularly in schools where each teacher has a supply budget or other allocation that could be pooled for purposes of the project. Of course, it is theoretically possible to overload the site, but even with several teachers involved, the number of students working on the site at any given time is likely to be manageable. Some teachers will only be interested in a short-term project, and even those whose students will be doing longer-term work will be meeting their classes at different times during the day. Students working on a site-related project after the end of the regular school day aren’t likely to all be working at the same time.

Assuming you have the budget, the approval, and at least a little digital access on campus to facilitate the system, which company should you go with? Having worked with both, I’d say Bluehost has better server performance. Neither one has significant downtime, but I did have some experience with GoDaddy becoming very slow at times. The least expensive plans are always going to involve shared hosting (multiple clients on the same server), which can mean that someone else being hosted on the server can conceivably cause demand for resources to spike and slow down your site. I did occasionally have that kind of issue with GoDaddy, but never with Bluehost.

Another advantage of Bluehost is that it has partnered with Cloudflare to enable you to manage a free Cloudflare account through Bluehost. You can get a Cloudflare plan regardless of hosting provider, but Bluehost’s handy integration enables you to get statistics and handle settings through Bluehost, making configuration easier. (You’ll want to at least try Cloudflare. Paid plans are available, but even the free plan provides considerable speed and security enhancements for your site.) Though you won’t need this enhancement for typical student projects, it’s a good concept to introduce to students, particularly those who want to be involved in international business. What Cloudflare and similar companies provide is a content delivery network (CDN), the benefit of which is to replicate your site on servers all over the world, so that viewers far distant from your hosting provider’s server will be able to load your website faster.

The trick with any system of this type is giving students the paradoxical ability to publish and still keep their material private, or at least publish only within your class. By trial and error, I worked out a way to use WordPress with precisely that effect.

Here are the plugins you’ll need to get the job done (all free). Please note that I have vetted all of these, and they worked well at the point I was using them myself. Obviously, I can’t guarantee that they will always work, particularly if the developers don’t update them, though you can probably always find another plugin that will do the job of an outdated one.

Restrict Content. This plugin enables you to specify differing levels of access. Make sure you have user signup configured to default to subscriber (lowest level), and when you are reviewing the registrations, you can bump the students up to contributor. If you decide to have students post for the whole class, it’s easy to configure the areas where they post to be restricted to contributors.

(copyrighted by LeoWolfert and licensed from www.shutterstock.com)

Agreeable. If your school and/or district has an acceptable use policy for students, your administrator will probably want you to enforce the same guidelines on the WordPress site, especially if district funds are paying for it. Agreeable requires anyone who signs up to agree to whatever terms you want to specify.

Better WordPress ReCAPTCHA. Since you need to vet student registration anyway, you may not need this one, but it will save you time by preventing some kinds of spam bots from signing up. (A totally open WordPress or other site will accumulate fake registrations very rapidly.) [Edit: This one hasn’t been updated in a while. You might want to try Advanced NoCaptcha and Invisible Recaptcha. Several alternatives are available.]

View Own Posts Media Only. Whether or not students will be sharing with each other, you or they may want raw materials and rough drafts to be private. This program prevents contributors from seeing the post titles and media uploads of others. (WordPress normally prevents contributors from seeing the actual posts of others before publication, but this plugin provides an additional layer of privacy.

WPFront User Role Editor. This plugin enables you to edit the contributor role to give students whatever capabilities you want them to have. For instance, it may be more convenient to have students prepare their work as a page, rather than a post, but page creation is normally reserved for higher level user roles. I don’t recall the details, but I do believe that contributors also have some issues with media uploads. You don’t want to give students roles that enable them to manipulate the overall site too much. This way you can keep them in a lower role but tailor the privileges that role has as you wish.

The combination of those plugins will enable you to adapt WordPress to provide the levels of access and privacy you need without having to spend hours creating your own system. In particular, notice that you can make different arrangements within the same site. Students can publish just for you (by setting visibility to private), just for their own class (through your configuration of the Restrict Content plugin), or to the whole world if the project involves created an online literary magazine or similar publication. The methods I discussed in the previous post could work for the first and third situations, but the second would be much trickier to pull off that way.

Classroom Applications

(copyrighted by Monkey Business Images and licensed from www.shutterstock.com)

You will probably need to spend some time in class introducing the various WordPress features. Students may not be used to the ability to switch between a visual editor and an HTML editor, and while they may be used to using graphics, tasks like embedding video, if needed, will require some explanation. If you’re using this kind of project in English, that’s probably as much time class time as you can devote to explanation, though I’d also recommend at least one session in which the students have Internet access, so that they can practice the basic skills under your guidance. A more specifically targeted class, such as one dedicated to web design, would naturally be able to spend more time on in-class instruction.

The kind of project you have the students do will naturally depend upon your course content. The Introducing Yourself project discussed in an earlier post is one possibility, but there many alternatives. The important thing is to use a project that forces students to use all of the important skills. Such a project would include text creation and layout (which they won’t have much trouble with), proper use of graphics (which they may have a little trouble with), proper use of embedded audio and/or video (which most of them initially won’t have a clue about).

Note that the basic setup I’ve outlined above can be adapted for much longer-term use. For instance, if journal writing is part of your class (as it might be in English, for example), some of that process can be done online to provide for additional skill practice and enhancement. If you are doing something even more ambitious, such as an online literary magazine, you can involve some or all of the students in making basic website decisions. Which free theme would work best for the magazine? Are there free plugins that would enhance the look or improve the user experience? (The latter is a good opportunity for getting future web designers to think about trade-offs, since elaborate themes and/or numerous plugins can indeed do wonderful things for function and visual appeal, but they can also slow down a site. Figuring out how to balance advanced functions and/or better appearance with performance is good decision-making practice. Students can use performance tests such as those offered by Gtmetrix to try out variations and get immediate feedback about how design changes affect loading speed and other variables. With Google and other search engines increasingly prioritizing site speed as a criterion for ranking sites in search results, any student who wants to design websites or run a business involving web presence could benefit from this kind of decision-making.

An Additional Suggestion for Longer-Term Projects

(copyrighted by michaeljung and licensed from www.shutterstock.com)

For those of you who are doing a longer project and have some money left in the budget, I’d suggest a premium theme to give the students a wider array of options with which to experiment. I’m a big fan of BeTheme, which this site uses. It costs $59, which is definitely pricey, but it does include three plugins (WPBakery Page Builder, LayerSlider, and Slider Revolution) that by themselves cost $46, $25, and $26, respectively, for a total of $97 if purchased separately. (The plugins can be updated only in conjunction with theme updates and can’t be used independently from the theme, but otherwise, they are full versions.)

Why that particular theme? Because it exponentially increases the options available, providing students with considerably more experiences in real-world decision-making. I don’t want to make this post into a BeTheme commercial, but I’ll briefly outline some of the features to give you an idea of what I mean.

As I mentioned above, BeTheme comes with two very powerful sliders (plugins that display content on a rotating basis, such as at the top of the home page and blog page on this site). Generally, the students wouldn’t need more than one for even a complicated project, but which one is better? Someone would have to experiment with them to determine which one best suited the project’s needs.