Daniel Sherrier's Blog, page 2

March 7, 2021

The Lamentable Plight of the Lonely Word

I hate it when I end a chapter with a single line stranded on a new page — or worse, a single word.

The poor lonely word sits there, cut off from the rest of its chapter, doomed to spend its days in isolation. Its existence becomes a torment. It knows its friends are all just on the other side of the page break, but a cruel twist of fate has separated it from everything it’s ever known, even the very subject it was born to serve.

Only a vast plain of Arctic whiteness stretches before the lonely word. Maybe there are more words beyond, with exciting new clauses to join. But the lonely word can never know, because it’s stuck here. Banished from civilization.

At least until I inevitably revise the chapter.

March 1, 2021

Taking Superman to the next level — parenthood

I’m happy to see the new TV series Superman & Lois is taking a cue from my favorite recent run of Superman comics.

Launching under the DC Universe Rebirth banner, this series took Superman to the next level—not in terms of epic storylines, a bold new tone, or even overall quality. For Superman, the next logical level was parenthood.

The series followed Superman and Lois Lane as they raised a 10-year-old super-son, trying to impart on young Jon Kent the same values that Jonathan and Martha Kent had imparted on young Clark back in the day.

It fit what Superman is all about, and it put Lois and Clark in a new status quo that suited both of them. We saw that even after eight decades, you can still do something fresh with Superman without betraying the character’s core premise. Not every issue was a winner, but the run as a whole was a lot of fun.

Superman & Lois isn’t copying the comic—they’ve got two teenage sons in the TV show—but it is recapturing the family dynamic to differentiate this Superman from his previous TV and movie incarnations.

I also appreciate that, even though it’s on the CW, it’s not following the same formula as the previous CW superhero shows. I enjoyed the early seasons of Arrow, Flash, and Supergirl, but it is time for a fresh approach. Based on the first episode, Superman & Lois is on the right track, and its own track.

February 27, 2021

WandaVision: A perfectly strange marriage of superheroes and sitcoms

I’m enjoying WandaVision for a host of reasons, and Iespecially appreciate what it demonstrates about superhero storytelling.

Superheroes can work in any medium, and different mediumscan open up new possibilities. It’s a versatile genre, and embracing thatversatility is to its (and our) benefit.

WandaVision is not the first excellent superhero television series. Among others, Daredevil was at times amazing, and I’ve been loving Doom Patrol so far. But WandaVision might be the first that can only be a television series (or streaming series).

The sitcom gimmick isn’t just a gimmick, nor is it parody.It’s occasionally adjacent to parody while always being a distinct entity. Theseries is playing with different tropes than superhero comics or movies get toplay with, and it’s employing those tropes to show what Wanda is going through.

And it doesn’t dispense with all comic book tropes in theprocess. The series remains part of a previously established shared universe,building on years of stories and pulling together various characters fromvarious sources. The plot incorporates elements from older comic book stories,but it’s all structured in such an original way that it stands on its own assomething new.

WandaVision is a strange, fascinating marriage of superherotropes and sitcom tropes, uniting them in innovative ways to offer somethingfresh for comic book readers and television viewers alike.

February 18, 2021

Morning Writing vs. Evening Writing: A Duel

When is the perfect time to write?

Trick question. But while there’s no perfect time, differentparts of the day do have different advantages. I’ve tried many, and I’ve goneback and forth on which one feels best for me overall.

Morning writing looks best on paper. Just get up and get towork, before the daily concerns of life can derail your creative process. Wakeup with a shower, eat a decent breakfast, and sit down at the computer with aclear, fresh mind. Knock out several pages, then tend to the rest of the daysecure in the knowledge that you’ve already accomplished some solid writing.

But it doesn’t always go that smoothly, at least not in mycase. I have a day job, so in order to give myself sufficient writing time, Iwould have to wake up around 5:30 a.m. or so. I tried that for a while. Somemornings went well. Others got off to a sluggish start, and by the time I was startingto build some decent momentum, it was time to stop and shift to my other workday. Then, after work, I was often so tired that I’d crash by about 9-9:30.

On the plus side, I got some of the best sleep of my life.But I’m really not wired to be a morning person. It’s nice to know that I canget myself up super-early on occasion, if the need arises, but it wasn’toptimal use of my time or energy levels.

Evening writing is a riskier affair. The pessimistic view isthat you’re putting writing at the mercy of how the day went. A rough day canwreck the night, and there’s increased temptation to drink too much caffeinetoo late in the day. I’m certainly guilty of letting myself get derailed for avariety of reasons, but it’s always ultimately my own fault. When I focus onthe key advantage of night writing, the results are much better.

That key advantage: I’ve already done absolutely everythingelse I needed to do that day. All other commitments are cleared out, and thebook becomes the only thing I need to focus on.

This usually gets me a longer stretch of writing timecompared to trying to cram in some morning writing. I’ll finish my day job, takea dinner break, read for an hour or so, and then there’s still plenty of nightleft for writing.

I can sneak some additional work in other parts of the day.An unfocused morning can still yield some productive brainstorming, andafternoons (on my days off, at least) are sometimes good for editing. But thoseare simply nice bonuses. For me, in my subjective experience, nights are whenthe best work tends to happen.

Then again, I don’t think I’ve ever tried writing at 3 a.m.Maybe that’s the top-secret perfect writing time?

January 24, 2021

Marvel’s Top Ten Stories: 1976-1980

I wasn’t born yet during this half-decade; nevertheless, I’mquite fond of many Marvel comics that came out of it. After all, this is theera that relaunched the X-Men and elevated them to greatness, with a longstring of all-time classic issues.

It should come as no surprise, then, that X-Men storiesdominate half this list. Really, the main question should be obvious: Will thetop spot go to the Dark Phoenix Saga or Days of Future Past?

And the other question: What non-X books make the cut forthe other half of the list?

(Please note: The 1976-80 time frame is by release date, notcover date, which makes all the difference for a couple of the honorees here …which I suppose foreshadows the greatness of the ’80s.)

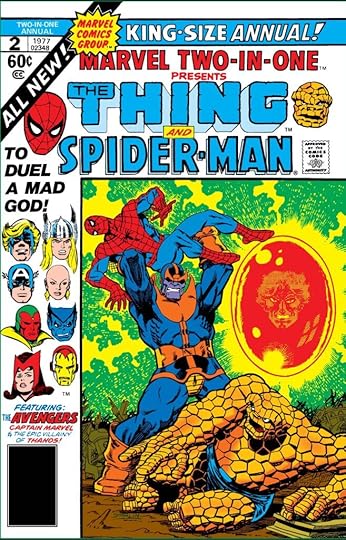

10) Avengers Annual #7, Marvel Two-In-One Annual #2(by Jim Starlin)

It’s like an early draft of the Infinity Wars, as well as providingthe sequel to Captain Marvel’s Thanos War storyline and the conclusionto Warlock’s long-running saga. Thanos has collected most of the Infinity gems(known as “soul gems” at this point), and he sets out to destroy the sun inorder to win the favor of Death herself. The Avengers, Captain Marvel,Moondragon, and Warlock, naturally, head into space to stop him. Great cosmicaction ensues in an epic tale about life and death.

Spider-Man and the Thing join the action in the second part,and Spidey’s presence in particular brings the human perspective to the mix.He’s out of his league. He’s scared. He even panics at one point. And thatmakes his contributions all the more heroic.

9) The Avengers #164-166 (by Jim Shooter and JohnByrne)

The Avengers vs. Superman! Well, not really, but it’s theAvengers vs. Count Nefaria with Superman-like powers!

The storyline features all-out action against an immenselypowerful foe who craves nothing less than immortality. Defeating such a menacewill require nothing less than the teamwork of Earth’s mightiest heroes. Theproblem—or another problem, rather—is the internal tension that puts theAvengers off their A-game. But it wouldn’t be a proper Marvel comic withoutfeuding heroes.

This one has all the elements of a thrilling old-schoolAvengers storyline: high stakes, a formidable threat, fast-paced action, and—mostimportantly—interesting character dynamics. Add that all together and you’vegot pure fun for comics fans young and old.

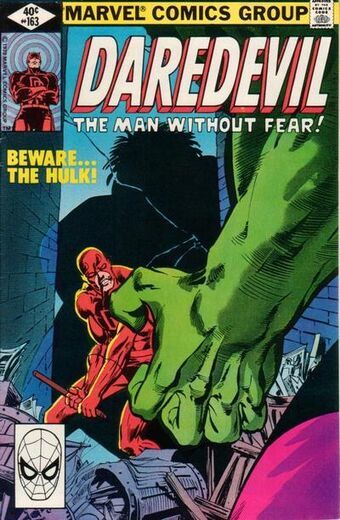

8) Daredevil #163 (by Roger McKenzie and FrankMiller)

Daredevil was already recovering from years ofmediocrity even before Frank Miller started writing the book (not to diminishMiller’s indispensable work at all). Issue #163 is a great example, with a verydown-to-earth story that shows us the real measure of the title character.

The Hulk shows up in New York, and he’s confronted by … MattMurdock, in formalwear. And ultimately, Matt just wants to help the Hulk, notfight him. He empathizes with the innocent man within the beast, and heunderstands how easily a Hulk situation can spiral out of control. If he canget the Hulk to calm down, and help Bruce Banner get out of town, great. And healmost succeeds.

Things go south when Banner hulks out again, and Daredevil realizes that he might be the only person who has a prayer of defusing the situation before it gets worse. Of course, one very human Man Without Fear is nowhere near the Hulk’s weight class.

As Daredevil tells himself after taking a beating: “Tried mybest … to stop Hulk. Best wasn’t … good enough. If I quit now, nobody wouldblame me … nobody would even know. Nobody … except me. I’d always know that Ibacked down … that I ran …”

Pretty much everything you need to know about Daredevil’scharacter is shown right here in one excellent issue.

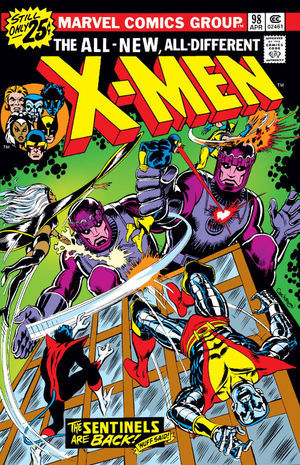

7) X-Men #98-100 (by Chris Claremont and Dave Cockrum)

The first great storyline of the X-Men’s “All-New,All-Different” relaunch. It begins as any good X-Men story should, with theteam enjoying some downtime, just trying to live their lives, until the world’sfear and hatred get in their way … this time in the form of mutant-huntingSentinel robots.

The Sentinels capture Jean Grey, Wolverine, and Banshee, whothen must fight their way through bigots and robots. They’ve been abducted to afacility at an unknown location, which proves to be much farther from home thanthey thought.

Part of the X-Men’s success has involved mixing and matchinggreat characters and watching them play off each other. The first issue givesan early example of that by pulling together three X-Men who had hardly everfunctioned as a team, and certainly not with just the three of them.

This would have been a solid anniversary storyline toculminate in the 100th issue, complete with facsimile robots of the originalteam. But the final three pages bring it to the next level. The highlyemotional scene, featuring Jean’s Big Damn Hero moment, portends just howamazing X-Men is going to get.

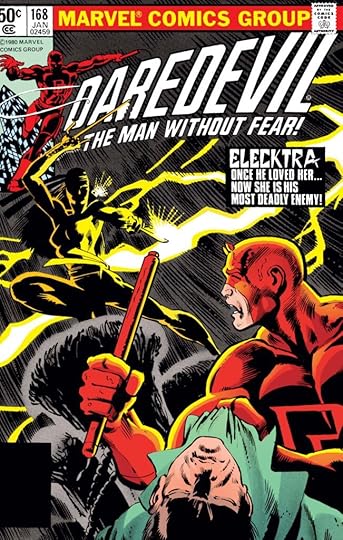

6) Daredevil #168 (by Frank Miller)

Frank Miller’s writing debut barely sneaks into thisfive-year period. True, the best comes later, but this is a strong start, afantastic introduction to a pivotal new character, and a great example of aretcon that works. Matt Murdock’s first great love, neither mentioned nor evenhinted at for 167 issues, suddenly emerges in issue #168. But who cares aboutsuch implausible oddities when said first love is as fascinating as Elektra?

Matt met her in college, when Elektra was the overlyprotected daughter of an ambassador. And, showing just how human he is, Mattthrew caution to the wind and showed off his athletic prowess and hypersensesto impress the girl. Tragedy separated them then, but now Elektra reenters hislife—by throwing her sai against the back of his head.

Daredevil’s ex-girlfriend has become a highly skilled bountyhunter. Further conflicts between the two are inevitable. But here’s what’skey: Miller’s script and art show how they both still care for each other, evenafter all these years. And the richer the emotions, the richer the conflicts.

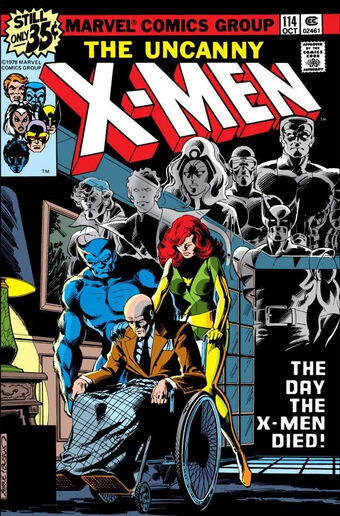

5) X-Men #111-114 (by Chris Claremont and John Byrne)

The classic Claremont/Byrne collaboration began a few issuesearlier, but this is where it really kicks into high gear, never losingmomentum from here on out. Right off, we’re dropped into the middle of amystery, with X-Man-turned-Avenger Hank McCoy serving as our very confusedviewpoint character for part one. The Beast finds the new X-Men performing ascarnival freaks and investigates.

And that’s merely our starting point. This littlemisadventure with Mesmero soon turns into a memorable confrontation withMagneto at his villainous best (or worst), a few years before actual characterdepth was retconned into him. He places the X-Men in a creative and cruel trap,leaving them physically helpless and babied by a robotic nanny day after day.

This merely sets the stage for a truly fantastic battlewithin a volcano, one that leads directly into the next exciting stories.

It’s pretty much all greatness from here on out for theClaremont/Byrne team. Comics as they should be.

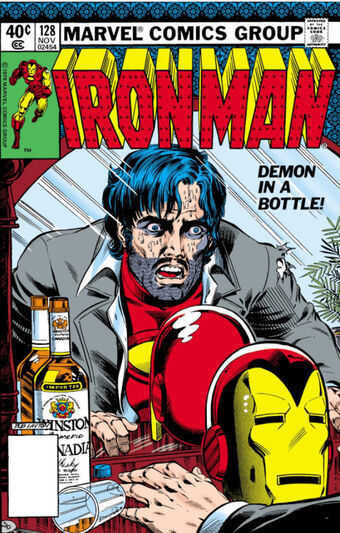

4) Iron Man #120-121, 123-128 (by Bob Layton, DavidMichelinie, and John Romita Jr.)

Iron Man faces his most insidious foe yet: alcohol. This could easily have veered into “after-school special” territory, and it does come close toward the end, but the storyline succeeds by weaving the alcoholism plot throughout several issues of otherwise normal (and very strong) Iron Man issues. Tony doesn’t immediately become an alcoholic in part one. His drinking gradually escalates, as do the detrimental effects.

At the beginning of #120, a stewardess asks Tony if he’ssure he wants another martini, and Tony quips to himself that he’s drinking fortwo. While fighting the Sub-Mariner, he does wonder if he maybe should have hadone less drink, but his Iron Man performance is more or less unimpaired. So far.

Issue after issue, stresses mount, cracks spread, and Tony’sdrinking increases, becoming a problem without his realizing it.

Another plotline involves Justin Hammer seizing remotecontrol of the Iron Man armor, which provides an appropriate metaphor forTony’s internal struggle. And it’s fitting that regaining control of the armor provesmuch easier than regaining control of himself.

(#122 omitted because it’s a filler flashback issue.)

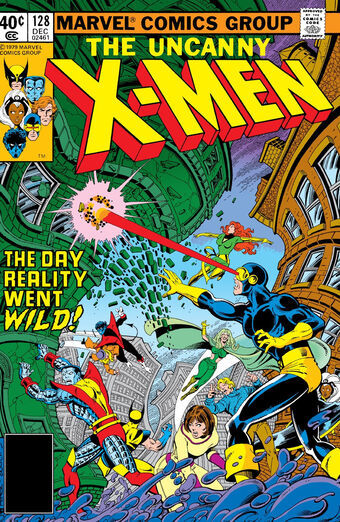

3) X-Men #125-128 (by Chris Claremont and John Byrne)

The X-Men confront their—and the world’s—worst nightmare: animmensely powerful mutant who lacks a conscience. To make matters even moretragic, this mutant is the son of the X-Men’s closest human confidant, MoiraMcTaggart.

Reality-warping Proteus pushes the X-Men to the limit. Even Wolverine is rattled. The tension never lets up until the end, and this gauntlet shows just how human, and strong, they truly are. Cyclops is in full leader mode, willing to do whatever is necessary to end the threat. Banshee, recently depowered, just wants to save his girlfriend. Colossus, confronted with pure evil for the first time in his young life, crosses a line he never thought he’d need to. And all along, Moira understands that despite her best efforts over the years, her son is beyond saving.

The story shows how evil doesn’t just come of nowhere, andsometimes, its origins are closer than we like to think. Proteus chose to focuson his father’s hatred rather than his mother’s love, and that tragic decisionputs everyone in danger.

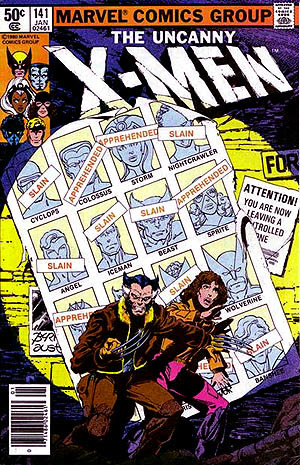

2) X-Men #141-142 (by Chris Claremont and John Byrne)

I’m somewhat biased against dystopian alternate-realityfutures, and yet I still love this short two-parter (which really could havebeen three or four parts, easily, without losing steam). It avoids what I likeleast about such stories—everything feeling inconsequential because it’sultimately an elaborate “what if?” scenario. But in Days of Future Past, eventsmatter. That’s kind of the whole point.

Present and future run along parallel tracks throughout bothissues. The future shows how everything has gone wrong, and the present iswhere a time-traveling visitor makes a last-ditch effort to set events on abetter path.

Present-day X-Men face off against the new Brotherhood ofEvil Mutants in a fun, conventional showdown, with an anti-mutant senator’slife in the balance (also featuring Storm’s debut as team leader).

“Meanwhile” … the few remaining future X-Men, with littleleft to lose, wage their desperate last stand against the Sentinels. Theirdeaths are all the more tragic because their world should never have reachedsuch a bleak state in the first place.

Additionally, we see young Kitty Pryde’s untapped potentialas her older self takes control in the present—demonstrating how even such adesolate future can bring out someone’s greatness.

These two issues make full use of the X-Men’s core premise to fashion a cautionary tale about how important the actions of today are.

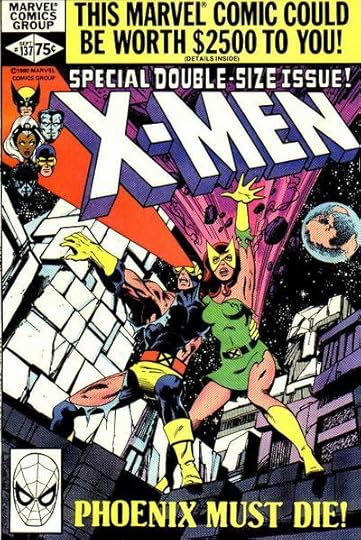

1) X-Men #129-137 (by Chris Claremont and John Byrne)

The Dark Phoenix Saga isn’t just the best storyline of thisfive-year period; it’s easily one of the best comic book storylines of alltime, showing off the medium and the superhero genre at their best. Superherostories excel when they balance the epic and the personal, the fantastic andthe mundane. Saving the world means a lot less if we neglect the characterspopulating that world.

These nine issues take us through an incredible run ofcomics. New characters: Kitty Pryde and Dazzler make promising debuts in therelatively quiet early issues. New villains: The Hellfire Club immediatelyprove themselves to be formidable adversaries. Old villain: OG Brotherhood ofEvil Mutants member Mastermind comes into his own with his gradual corruptionof Jean Grey. Ongoing subplots: Jean acquired cosmic-level power nearly thirtyissues earlier, and the payoff is imminent. Romance: Scott and Jean arereunited after a long separation and are more in love than ever. Iconic soloaction: Wolverine continues to solidify into the Logan we all know and love ashe’s let loose against the Hellfire Club. And so much more.

But at the core of all this is Jean Grey and her struggle toavoid being corrupted by her newfound power. And she fails—worse than anyMarvel character has failed before or probably since. In her power-fueledmadness, she consumes a star and destroys a planet populated by billions. Andirredeemable action, but who’s responsible? Jean or the Phoenix force?

The X-Men choose to believe in Jean’s inherent goodness, and they put everything on the line in order to save their friend. Saving their friend is saving the universe. But in the end, Jean herself knows what really needs to be done, and what only she can do. In doing so, she proves the faith her friends put in her.

There might be better comics out there, but if so, you cancount them on one hand.

November 21, 2020

The Untouchable MC Hammer

I was thinking about MC Hammer the other day. Not voluntarily, of course. One does not call Hammer time; one simply answers the call.

In MC Hammer, we have a man grappling with the conundrum of his own existence. He fashions himself with a name that implies hard-hitting physical contact, then announces to the world that you cannot touch this. He poses the rhetorical question, “Why would I ever stop doing this?” And then he answers it, structuring an entire song around the insistence that he is “too legit to quit.”

The existential anguish is unmistakable. He cries out for his own legitimacy, employing repetitious lyrics to hammer (if you will) the intangible point.

Around the same time, in his animated series Hammerman, he even goes so far as to transform his likeness into a cartoon, stripping himself of an entire dimension of being to see what remains. It’s as if he implicitly understands he should not exist as he is, and yet exist he does.

Through everything, he overcomes the self-imposed adversity of his own baggy pants and he keeps dancing, becoming the ultimate paradox: a one-hit wonder with multiple hits.

MC Hammer at once makes no sense and perfect sense.

But does the rapper protest too much? How could he do otherwise?

I think there’s a little MC Hammer inside each and every one of us.

September 15, 2020

Marvel’s Top Ten Stories: 1971-1975

I ranked my favorite Marvel Comics stories of 1961-65 and 1966-1970 a while back, so it’s long past time I examined the next five-year period.

The early 1970s isn’t my favorite Marvel era, but it’s definitely a fascinating one, as well as an improvement over the late ’60s (which needed some shaking up). In a way, it’s almost like a proto-Marvel Cinematic Universe. The X-Men have been sidelined. The Fantastic Four have waned. Spider-Man’s still going strong. The Avengers are on top. Thanos is coming into prominence as one of the most powerful villains in the MU. Marvel’s original Captain Marvel is enjoying his heyday. And all sorts of interesting new characters are joining the mix.

It’s also an era of comics creators breaking free from past

constraints, with new titles, new genres, new ideas, and bigger, longer storylines

that occasionally delve into philosophy and social issues.

So, here’s what I consider the best of this bunch (45+-year-old

spoilers ahead!) …

10) The Avengers #113 (by Steve Englehart and Bob Brown)

Vision and Scarlet Witch’s romance goes public, and while

most people are excited for them, a small group of bigots decides this is the

end of civilization as we know it—androids are going to replace us! So, like

bigots do, they turn themselves into living bombs so they can blow themselves

up and take the Vision with them.

In this straightforward, single-issue story, the Vision and

Scarlet Witch represent the interracial couples of their day, the homosexual couples

of the future—really, anyone whose lifestyle is met with unreasoning hostility

in any era. Interestingly, the bigots depicted in the comic are a multicultural

group; even though they’ve overcome their racial prejudices, they’ve latched

onto a new excuse to hate someone for being different. And their hatred

ultimately infects the Scarlet Witch, renewing the mutant’s animosity toward

humans, even though the overwhelming majority of humans were supportive of her

and the Vision.

The comic isn’t subtle, but rather than just preaching, it

shows us that hatred is destructive, unreasonable, and, sadly, cyclical.

9) The Incredible Hulk #140 (by Harlan Ellison, Roy Thomas, and Herb Trimpe)

In quite a few early Hulk comics, Hulk was just looking for

a place to belong. He was, in a way, undergoing the hero’s journey home—even

though he had no idea what “home” was. With this Harlan Ellison plot, we get the

best of this Hulk genre so far.

The Hulk is stranded in a subatomic world, where he

inadvertently saves a kingdom of green-skinned people, immediately earning

their adoration. Bruce Banner’s brain takes over Hulk’s body, and he becomes

engaged to the queen of this world. He’s respected and admired, and he has much

to offer. He’s not a monster here. So of course it’s all going to get ripped

away from him.

The ending has a perfectly tragic touch. As the Hulk reverts

to his usual brainless self, he’s vaguely aware of the happiness he had, and he

bounds off in search of that place—unaware that it’s within a mote of dust

clinging to his clothes.

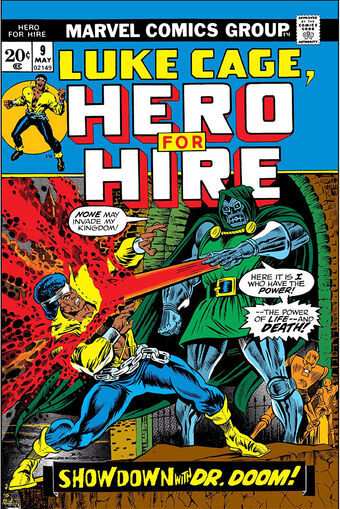

8) Luke Cage, Hero for Hire #8-9 (by Steve Englehart and George Tuska)

One of the joys of the Marvel Universe is the never-ending opportunity

to pair wildly divergent characters who have no business being in the same

book. And one especially delightful example is when Doctor Doom hires Luke Cage

to track down some runaway robots hiding out in New York.

The second part is where the fun kicks into high gear. After Doom stiffs Cage on the payment, Cage borrows transportation from the Fantastic Four and flies all the way to Latveria to collect his bill. He stumbles into the middle of a revolution already in progress, having no allegiance to either side—just his own values.

It’s a ridiculous scenario that paints a vivid picture of what kind of man Luke Cage is.

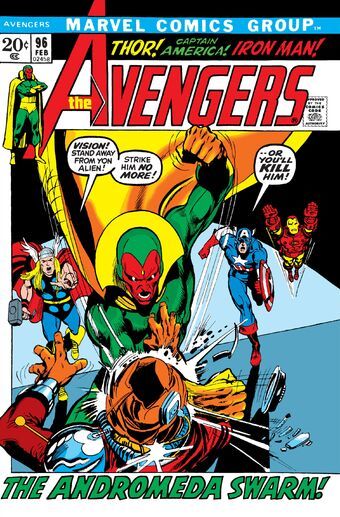

7) The Avengers #89-97 (by Roy Thomas, Sal Buscema, Neal Adams, and John Buscema)

The Kree-Skrull War makes a great bridge from Marvel’s

Silver Age to its future. It’s a sprawling epic, at different times both micro

and macro in scale, one that draws inspiration from recent real-world history as

well as Marvel history. There’s a thinly veiled McCarthy figure over here and

an android in love over there, plus a loose end from an old Fantastic Four

story tied up for good measure—all that and more inside the framework of an

interplanetary conflict, with Earth caught in the middle.

If anything, there’s too much going on, so much so that the Avengers themselves nearly get lost in the shuffle sometimes, but part of the charm is the unbridled imagination at play as Marvel breaks into new storytelling possibilities while respecting what has come before.

6) The Amazing Spider-Man #96-98 (by Stan Lee and and Gil Kane)

Spidey fights drugs! The storyline’s main claim to fame is

defying the Comics Code Authority to actually show drug use rather than just

preaching against it. There’s still some preaching within, but the showing bolsters

the message. And by weaving the message into exciting superhero action and

relationship drama, Stan Lee elevates these issues into a classic.

The Green Goblin remains Spidey’s most compelling villain of

the era. His knowledge of Spider-Man’s secret identity raises the stakes, and

the fact that he’s the father of Peter’s best friend adds another layer of

tension and gives Spidey the opportunity to appeal to the humanity beneath the

garish mask.

5) Doctor Strange #1-2, 4-5 (by Steve Englehart and Frank Brunner)

An anti-magic zealot stabs Doctor Strange in the back and

kills him. Or does he? Strange’s attempt to flee death itself plunges him into

a surreal odyssey through “unreality.” He’s dying, and nothing makes sense

anymore, as a guest appearance by the Alice in Wonderland caterpillar makes

abundantly clear (or unclear?).

What starts as a struggle for survival takes on greater

meaning, as Strange learns it’s not enough to merely continue living. To beat

death, he must conquer his own fear of death. Death is inescapable, after all.

And as Strange conquers this fear, the story highlights the distinction between

knowledge and wisdom. This is Doctor Strange as it should be—juggling big

ideas and memorably weird visuals.

(Issue #3 omitted since it’s mostly a reprint.)

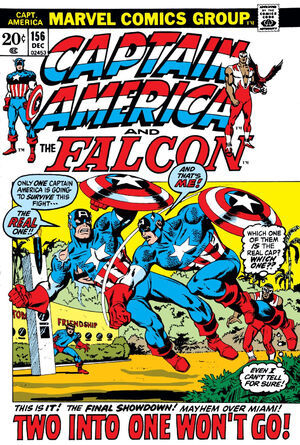

4) Captain America #153-156 (by Steve Englehart and Sal Buscema)

Captain America vs. … Captain America? Marvel had previously

attempted to resuscitate the character of Captain America (with sidekick Bucky)

in the 1950s. It didn’t work out nearly as well as the next such attempt in the

’60s.

And out of this piece of Marvel trivia, writer Steve Englehart manages to simultaneously turn forgotten stories into canon and confront Captain America with his own potential dark side. Cap sees himself as he might have been—so consumed with blind patriotism that he descends into bigotry and madness.

Recasting the 1950s Captain America as a failed successor may be a retcon, but it’s a retcon with a purpose, one that shows just how exceptional the real Captain America is.

3) Captain Marvel #25-33, The Avengers #125 (by Jim Starlin and friends)

This wasn’t the first Thanos story, but it was the first

Thanos epic and the first time he used a supremely powerful artifact to attain

godhood. This also happens to be the best the original Captain Marvel series

ever got.

Captain Marvel, at this point, is less a character and more

an avatar of self-actualization. He’s linked with perennial sidekick Rick

Jones; only one can exist in the universe at a time. Rick has long since been

the young reader’s stand-in character, and Captain Marvel is, in a sense, his

stand-in character, representing the stalwart superhero Rick and the reader

have always yearned to be.

During the course of the Thanos War, Captain Marvel evolves,

transcending his warrior past to become a universal protector with cosmic

awareness. Thanos, meanwhile, uses the Cosmic Cube to elevate himself into a

god, but he’s unable to leave his ego behind—and that’s his downfall. Both

Captain Marvel and Thanos ascend, but only one does so with wisdom. It’s not so

much a superhero story as it is a cosmic tale of philosophy, using aliens to

explore human nature. And it’s all written and drawn passionately and exuberantly.

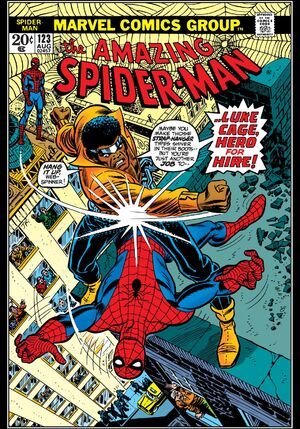

2) The Amazing Spider-Man #123 (by Gerry Conway, Gil Kane, and John Romita)

The runner-up is the follow-up to the #1 story. We spend an

issue dealing with the consequences of Spider-Man’s failure, and Spidey works

through the anger stage of his grief by battling Luke Cage, hired by J. Jonah Jameson

to bring Spider-Man in, dead or alive, for the murder of Norman Osborn.

Superheroes meeting while fighting is hardly uncommon, but

as a nice change of pace, this fight feels organic. Cage is just doing his job,

and throughout the altercation, Spidey and Cage keep pushing each other’s

buttons, escalating the conflict further. Meanwhile, various subplots brew. Previous

comics on this list might be more ambitious in scope, might tackle bigger ideas,

but this one excels all the more by focusing on character.

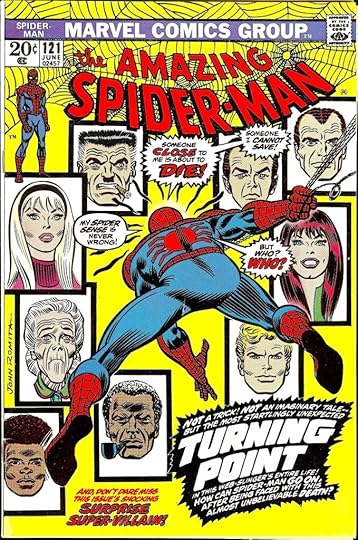

1) The Amazing Spider-Man #121-122 (by Gerry Conway and Gil Kane)

Remember on Seinfeld when they wanted to get rid of George’s fiancé, so they just casually killed her by having her lick toxic envelopes? The Amazing Spider-Man had a similar problem, and similar solution, but the execution was so much better (and devoid of toxic envelopes).

Peter Parker’s girlfriend, Gwen Stacey, wasn’t working out

story-wise. There was nowhere for the character to go. She simply wasn’t that interesting,

but Peter loved her and there was no plausible way to break them up other than to

keep wedging Spider-Man between them.

So they killed her. But they made the death count, dealing Spidey his most tragic failure yet, one that would continue to haunt him as much as Uncle Ben’s murder. Gwen’s murder occurs during a climactic conflict with the original Green Goblin, a quarrel that brings Spidey right up to the edge and requires him to be strong and decent enough to step back from that edge.

And the final page, where Mary Jane awkwardly attempts to comfort Peter, is a work of beauty and says so much about both characters, using relatively few words to do so. A masterpiece of superhero comics.

August 20, 2020

Time for an experiment — one month without social media!

I’m going to experiment and try a month with no social media whatsoever, August 22 – September 21.

I shall take the red pill and unplug from the Matrix. Granted, I run the risk of finding myself in a dystopian wasteland in which machines have conquered the world and are using everyone I know as living batteries, but that’s a chance I’ll have to take.

I won’t be checking any notifications during that month. I’m sure Facebook will send me emails telling me I have notifications, but I’ll ignore those and carry on with my day. And then Facebook will no doubt email me again, informing me that so-and-so has shared a link! And Friend X has liked Friend Y’s photo! And Friend Z has posted an update! Don’t you want to see what Friend Z has posted? Don’t you? Don’t you?

I wonder how desperate Facebook will eventually get? Will it show its true colors and go full-on General Zod? “You will bow down before me, Facebook User. I swear it, no matter that it takes an eternity! You will bow down before me! Both you … and then one day … your heirs! “

This will be not only a month with no Facebook, but also a month with no Twitter, Instagram, or even Goodreads. No YouTube either, as that counts as social media (though I may make exceptions for legitimate research or practical how-to videos, if needed). Scrolling will not slay any of my time.

If you really miss me, there’s a certain superhero novel that’s worth hundreds and hundreds of posts … and whose sequel I’m very behind on because I keep thinking of better ways to do it. That will be the priority during this month.

Behave yourselves while I’m away.

August 1, 2020

Muppets aren’t supposed to focus on ‘Now’

Muppets Now premiered on Disney+ July 31, and of course I had to check it out. Unfortunately, something about it felt off.

I appreciate the intent, and it certainly comes closer to the mark than the misconceived Muppet series on ABC a few years ago. But it’s just weird to watch the Muppets stringing together what’s essentially a collection of YouTube videos.

At first, it struck me as anachronistic. Perhaps the Muppets simply belong in the ’70s and ’80s.

But that’s not it. The Muppets are supposed to be theater folk, always just barely pulling together a show in a specific, solid place. A theater not only gives them a home, but it also makes them timeless.

A streaming-based show feels very current year. A theater-based show can be any and every year. The only thing dating a Muppet show should be the very special guest star. Kermit singing “Happy Feet” on the original Muppet Show entertained me in the ’80s, and I’ll never forget my oldest niece cracking up at the same sketch circa 2013.

Muppets are ageless, and in a way, they almost exist outside of time. Muppets Now has potential, but I’d rather they stick to the formula of the original series and aim for another timeless classic.

Speaking of The Muppet Show, why isn’t that on Disney+? And why didn’t the fourth and fifth seasons ever come out on DVD? The world needs classic Muppets.

July 19, 2020

Watching Disney’s earliest movies for the first time

I watched the earliest Disney movies recently. I was curious

from the historical perspective, particularly after having read the excellent

biography of Walt Disney by Neal Gabler. I’m about to spoil these movies, but

you’ve had eight decades to watch them.

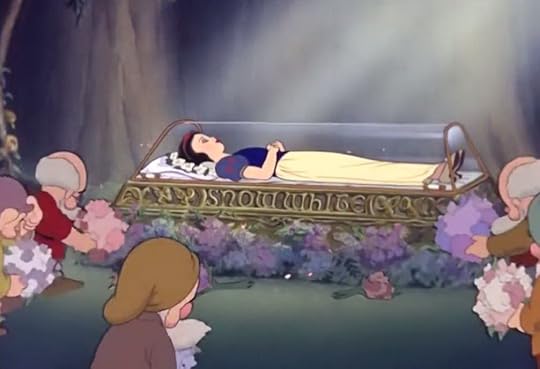

Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937): Walt’s labor of love, and a movie with massive cross-generational appeal when it was released. The animation is indeed superb, but I couldn’t get into the story, perhaps because Snow White never really triumphs at all. The last thing she chooses to do is bite into the poison apple. She doesn’t save herself. She never defeats the evil queen.

There’s really no reason for the queen’s failure. What are the odds that lightning would strike at exactly that wrong spot at exactly that wrong time? Or that seven dwarfs would want to look at a dead girl for several months instead of burying her? Or that Prince Charming would want to kiss a girl who’s been dead for that long? Some evil queens have all the worst luck.

Pinocchio (1940): This movie was far less successful during its initial release, but I found it to be more interesting than its predecessor. It’s incredibly dark at times. That Pleasure Island scene is a horror movie within a children’s movie. All those boys turn into donkeys and never turn back. They clearly know what they’ve become and retain the knowledge of who they were, but it’s too late, and they’re sold to perform slave labor for the rest of their lives. The movie has multiple villains, and none are brought to justice. As Pinocchio gets his happy ending, they’re all still out there, looking for their next victims. All I could think of was the catchphrase of Melisandre from Game of Thrones: “The night is dark and full of terrors.”

And let’s not overlook Pinocchio’s death. He dies even more thoroughly

than Snow White did. Though he can breathe at the bottom of the ocean, he’s

evidently unable to breathe at the top, so he drowns to his death. We see him

face-down in the water, dead. He’s eventually reborn better than ever, of

course, but he has to literally die to become a real boy.

Earlier, we also see him getting high off a cigar. This

movie pulls no punches. The kids of the ’40s were a hardy lot, and adults clearly

didn’t bother hiding the fact that the night is dark and full of terrors.

Fantasia (1940): The perfect movie to have on in the background as you’re doing something else. Though an interesting experiment, it’s no wonder the format never caught on, and it’s no surprise that the best segment is the one with the strongest narrative. “The Sorcerer’s Apprentice” is excellent. The rest varies.

Dumbo (1941): Dumbo is an even more passive protagonist than Snow White (if you can even call either of them protagonists). Other characters shun and humiliate him, and he just takes it. His mother sticks up for him, and she gets locked up for it. His mouse friend hypnotizes the ringleader into giving him a chance, but Dumbo is too hesitant to properly seize the opportunity given to him.

Poor Dumbo is trapped in a downward spiral until he

accidentally drinks a lot of alcohol and wakes up in a tree, leading to the

realization that he can fly. Then, like Spider-Man before Uncle Ben’s murder,

Dumbo uses his super-power to pursue fame and fortune. The End.

It’s an odd movie. Pinocchio’s journey had a clear purpose—to

teach kids life lessons through metaphor (and perhaps scare them straight).

Cigars nearly make a jackass out of Pinocchio. Alcohol leads Dumbo to a

breakthrough of self-discovery. The message is supposed to be about believing

in yourself, but there had to be better ways to get there.

Also, Disney+ warns that the movie “may contain outdated cultural

depictions.” “May”? Are they on the fence about the roustabouts and crows?