David Teachout's Blog, page 3

October 4, 2019

Losing Sight of the Real You

Imagine looking in the mirror and seeing someone else’s face. Frightened? Confused? Wondering whether you’re dreaming? The level of concern here connects us to why we get frustrated when other people don’t seem to see us accurately. We act in an ‘as if’ universe, where our behavior is done ‘as if’ it is as immediately understandable and clear to everyone else as it is to ourselves. When the reality that others don’t have immediate clear access to our own minds comes crashing down with all the weight of their judgment, there’s often an immediate feeling of annoyance, if not outright anger.

I believe the pure relief and, often, joy of ‘being seen’ makes sense when placed against the backdrop of living a life in a world that doesn’t conform to our ‘as if’ belief. There’s a weight lifted and that release forms many a basis for love and intimacy. Of course it does. Who wouldn’t want to create a life with someone who, out of the thousands that came before, takes away the constant wariness of looking in the mirror of our social interactions and possibly not seeing our own face?

Why is it, then, so difficult for others to understand us? We’re the same species. We’re using the same words in sentences that, in a specific culture, are generally accepted as having a common meaning. While we will accept that other people don’t have access to our inner mind, this seems a small thing. Unfortunately it isn’t small. It’s not even large. It’s the whole problem.

Past, Present, Future

In this world of digitized behavior, kept for all eternity, the human proclivity to organize the present in line with the past has gotten enormous support.

In a nutshell, people will interpret your current behavior in a way that makes it consistent with your past behavior, and they will tend to play down or completely ignore evidence that contradicts their existing opinion of you. What’s more, they will have no idea that they’re doing it.

Psychology Today

The quote from Heidi Halvorson above is perhaps a bit more positive than warranted, in the sense that people will “have no idea” they’re ignoring evidence to the contrary of a set opinion. On the contrary, quite often evidence to the contrary is deliberately dismissed as being aberrations, as detours from the ‘true’ reality of the person being judged. This dismissal is particularly strong when judgment is joined with identity. In other words, it’s not simply that a behavior is wrong, it’s that the behavior is representative of their associated race, gender, social group. Any contrary behavior to this homogenized story will be dismissed as belonging to a long con or other form of manipulation.

There is a space in which people are unaware they’re ignoring data, often in the day-to-day minutiae of life. Ever been driving and suddenly came to the realization that you don’t remember the last several miles? This detached or autopilot thinking happens fairly often, especially when a job is repetitious or a person feels no sense of ownership for what they’re engaged in. We can acknowledge this tendency while still pointing to how certain ideologies seem to support doing so deliberately. Anytime in which a part of someone is taken to be the whole, rest assured there are a great many variables/aspects/characteristics/behavior being dismissed.

The First Will Be Last

First impressions are, as the oft-repeated advice goes, very important. The strength of these first impressions is intimately tied to the degree of cognitive/emotional weight given to a situation. As noted above, that weight is shifted and focused more fully based on ideologies that parse people into singular identities, rather than whole people who contain multitudes. That said, seeing a random person on public transit will not generate many associations and you likely won’t remember them if you were to see the person later. If, however, they had been belligerent to you personally, or had engaged in behavior deemed bizarre, then later there’d be a quick judgment applied. Also, a random person will generate weaker associations than someone you’re interviewing for an important job or who shows up to take your kid out for a romantic date.

In other words, information we get about a person early in our observation of them influences how we interpret and remember everything that comes after.

Psychology Today

Early impressions are within the same mental spectrum of bias, but they’re stronger precisely because they’re fed by other biases and themselves become one. Indeed, first impressions are encouraged to be especially defining because they’re so often associated with one’s intuition, a form of knowing felt to be pure.

Importantly here is recognizing that, whatever the limitations of first impressions may be, the influence is ongoing. We will actively interpret a person’s behavior, not based on the intent of that person, but on the story we already have of them. Further, our memory will follow suit, selectively recalling the information that fits that story as well.

It’s the Relationship

So how do we learn to mitigate these influences? How do we start to live in such a way that the lack of our access to other people’s minds is not just acknowledged but constrains our own behavior? First and foremost, we need to look at how we construct our perspectives, namely through relationship.

Perspective and the communication based off it, is too often assumed to be like lobbing a ball back and forth over an invisible line. Each person has their space and they receive the proverbial ball whole and complete exactly as intended. The complete error of this metaphor cannot be overstated. At best what is going on is the communication ball is being shaped by the interweaving of at least six variables or threads as it moves from one person to another.

Intent of person AHistory of person AEnvironmental context(s)Intent of person BHistory of person BAutomatic biases of A and B

None of these threads are singular in themselves either. The history and intent of a person will be a build-up of learned assumptions based on all the interrelationships they’ve had throughout their lives. Nobody can have access to all that. For that matter, nobody has conscious access to all those pieces of information for themselves.

The best we can do, and it’s really not as depressing as it may initially look, is to take a pause before or very quickly after each judgment we have. Within this pause, we can consider how much the story we have about the other person is about our own judgments and the influences of our many layered context. Within that pause we can learn to listen more, speak less and seek first a greater understanding of our fellow traveler in humanity. Judgment is undoubtedly going to happen, but we don’t need to hasten its arrival.

The post Losing Sight of the Real You appeared first on Life Weavings.

September 26, 2019

Pathologizing Human Behavior

There is much research noting how, when it comes to bad behavior, we excuse our own by pointing to external variables and blame internal unchanging qualities for others. Further, we like to give rationales for all behavior, to place each exhibit into a personally coherent narrative and create an individualized museum dedicated to life’s exploration. Unfortunately, like any archeological dig, we are only able to see what we’ve currently dug up, what we’re currently focused on. There are any number of other behaviors lost to history or simply not being looked at.

In science there’s a built-in mechanism for continuing to ask questions and a peer review process to help doubt flourish even after conclusions have been reached. When it comes to humanity, there is no built-in process, it has to be taught, practiced and actively engaged in continuously.

The result of all this is a tendency to make what is normal human responses within disparate social situations, into glaring pointers towards pathology. A person lies and it’s a sign they’re a sociopath and pathological liar. A person experiences variations in mood and it’s a sign of bipolar disorder. Periods of sadness are now major depressive disorder. That the person in question faced a difficult choice, went from a challenging environment to a supportive one and is working through a loss, respectively, are all side-notes to the need to identify something aberrant.

Podcasts can also be listened to on iTunes, Soundcloud, Libsyn, and Google Play.

For more information on “Humanity’s Values,” check out the main page.

Your support is deeply appreciated and allows me to keep bringing you the content that you appreciate. Below you’ll find a button to set up a single or recurring donation through PayPal. Any amount is appreciated and ensures you’ll never hear advertisements.

The post Pathologizing Human Behavior appeared first on Life Weavings.

July 16, 2019

The Story of Your Anger

We like to think of our emotions in neat and tidy labels, as if they’re picked out from a carnival game, the claw of our consciousness selecting the right one. Adding to this narrow vision of our lives, we then place judgments on our feelings, claiming some are “good” or “bad,” putting us in the unenviable position of classifying entire sections of our lives as being abhorrent. Little wonder so many people come into therapy wanting to “get rid of” their emotions, or “reduce” them, or “gain control.” At the end of the day, when we cast our mental eyes back on our experience, it becomes painfully obvious that our emotions did not arise by our choice and so rather than be able to consider them from the perspective of our animal history, we then take those judgments and apply them to the whole of who we are.

Podcasts can also be listened to on iTunes, Soundcloud, Libsyn, and Google Play.

For more information on “Humanity’s Values,” check out the main page.

Your support is deeply appreciated and allows me to keep bringing you the content that you appreciate. Below you’ll find a button to set up a single or recurring donation through PayPal. Any amount is appreciated and ensures you’ll never hear advertisements.

The post The Story of Your Anger appeared first on Life Weavings.

June 28, 2019

Sharing Humanity Within Conflict

Raised voices. Increased heartrate. Narrowed vision. All the physical hallmarks of a discussion that devolved into argumentation and conflict. That these same physical experiences can also be seen when participating in a game with a team or during intensely intimate moments with one’s partner, should make us pause. We quite quickly write a particular story to provide us direction for our behavior, but the ease with which this occurs can blind us to how else life is lived. If there’s even a shred of dissonance in your mind right now, that’s actually a good thing. Growth, personal and group related, occurs at the edges of comfort, not at the center of contentment.

Seeking Shared Values

At the heart of so much interpersonal conflict is seeing the other person or party to be devoid of anything shared with oneself. The groundwork for doing so is established through the dismissal of similarity, of what we share as human beings. It isn’t enough to rest there though, since to ‘be human’ is too vague. What we can start with is recognize our capacity to care about parts of life and identify those things through the naming of Values.

Declaring someone or a group ‘doesn’t share my/our values’ has become the go-to place for easy dismissal. The reality is that one of two things is happening: one, the means through which the value is being supported is not agreed with, and/or two, the value for which the behavior is supportive is not the same across both parties. Consider working late at your job and someone judges you for it, declaring you don’t value ‘family.’ One, this may be how you’re supporting family and two, when deciding on your behavior, the initial guiding value was of financial security or personal integrity. In both perspectives ‘family’ is not dismissed. The only person seeking to remove that value is the person passing judgment.

Notice that in the dismissal, the lack of engagement is the point. Once the other is made ‘other,’ there’s no reason for dialogue as there’s nothing in common to start the conversation. The person passing judgment wins by default of them declaring a wall around what is and isn’t a proper way of viewing your behavior. The whole of human experience is then limited to their singular place within reality. All else is subordinate. You cease to exist as an autonomous agent within the broad spectrum of human potential. There’s no exploration and therefore no possibility of growth for either party.

Connecting Stories

Life is not the book of mazes you picked up for entertainment as a child. There is no single path to the end because the end is more like a mountain range of many peaks instead of a dot on a map. This is good news as it means the potential for human flourishing is varied. You don’t have to be doing the same thing as another to find meaning, purpose and to live ethically.

The ultimate end of human acts is eudaimonia, happiness in the sense of living well, which all men desire; all acts are but different means chosen to arrive at it.

Hannah Arendt

Connecting our behaviors to what we care about, our Values, requires stories or narratives. We move within the world through the roadways and paths laid down by our stories. Unfortunately, any time we focus to exclusively on the path we’re on, we tend to not see what’s around us, including other potential or actual paths. In this day of Google Maps it’s easy to narrowly consider one and only one way to get to a destination. However, try bringing out an old-school physical map or simply not have the AI tell you where to go, instead opting to view the broader map and decide for yourself. Odds are you’ll both see more and find routes you otherwise never would have thought possible.

Seeing the other pathways is key to understanding other people or groups. This isn’t about agreement, it’s a concern for exploring the variations in human expression. If you’re able to step back from behavior and see the story of how a Value was attached to it, suddenly there’s the potential for a dialogue that otherwise was impossible.

Photo by Eric Ward on Unsplash

Photo by Eric Ward on UnsplashAccepting Differences

Dialogue has recently been receiving a bad reputation. To have a conversation with someone has suddenly been conflated with agreeing with them, as if giving someone a ‘platform,’ whatever the size, is a declaration of support. The principle simply doesn’t hold, else we’d have to say support every thought that finds itself on the platform of our conscious lives. Not sure about you, but disagreeing with things that enter my mind is part of good ethical practice.

Acceptance is the space within which disagreement has room to be healthy rather than dismissive. Acceptance isn’t agreement, nor is it lazy. Acceptance is an acknowledgment of that the state of affairs, whatever they may be, is part of the shared reality you’re in. I accept thoughts of depression, not to give them voice, but to acknowledge they’re already a voice. I accept my feelings, not because they’re always helpful, but to have them take up the space they already have instead of giving them more than they deserve.

The opposite of Othering is not “saming”, it is belonging. And belonging does not insist that we are all the same. It means we recognise and celebrate our differences, in a society where “we the people” includes all the people.

John Powell

Accepting different behaviors is to appreciate the cognitive dissonance at the heart of life. We can disagree while acknowledging that if circumstances were different, and they most certainly have been in the past, we’d be doing things we find objectionable upon later judgment. Seeing that possibility allows us to live through the wisdom of “there but for the grace of god, go I.” Our shared humanity includes the good, the bad, the gray and uncertain. Being willing to wade into dissonance, into conflict, with a desire to understand starts with noting none of us have humanity exclusively to ourselves.

Featured photo by Richard Lee on Unsplash

The post Sharing Humanity Within Conflict appeared first on Life Weavings.

June 4, 2019

Culture as Reality Shaping

Communication is more than words being exchanged between two or more people. It’s also more than the non-verbal physical cues made famous by such shows as “Lie to Me.” When people engage in dialogue, they’re seeking to build a relationship of perspective with reality and, if reality doesn’t fit quite well enough, get the other person(s) to agree regardless. This is true whether the discussion has to do with broad, socially significant, political opinions or the varied intimacies of one’s emotional state.

The significance of binding perspective to reality cannot be overstated. Opinions aren’t just mental states, they’re the means through which we gather the disparate pieces of reality and bind them to create an experience. That we all like to be right begins to make sense here, given the potential weight carried by our thoughts. Combine these two points and the many forms of communication can be seen in a new light.

We can start with cultural practices.

Dialogue with Humanity

Contrary to the majority of felt experience, our thoughts are rarely unique creations. They’re far more likely to be derivatives from our social upbringing and cultural backgrounds, to promotions of something we recently read and likely didn’t critique long enough. The latter is especially fun in conversation if confronted by someone who does immediately know more than we do, as our shallow understanding is highlighted. Did I say fun? I meant embarrassing.

The reason for the non-careful assumption inherent of many of our opinions depends on how critical you want to be about our humanity. For those with a more negative view, it’s due to our inherent laziness as thinkers. A more reasonable take has to do with time-management. It’s simply easier to assume that the information we personally encounter is more likely true than not. Taking the time to critically analyze everything that crosses our mental space is not only impossible (since a great deal is unconsciously taken in), but it’s really poor resource-management. We’re far too busy living our lives to halt at every thought.

Photo by twk tt on Unsplash

Photo by twk tt on UnsplashOne of those ways we’re living is through culture. Consider cultural practices as mental shortcuts to meaning. Ever had a word that you used but didn’t know if it was the right one? Or hear one that you didn’t know the definition of? Sure you could look it up on you smart phone, but that takes time. Better if everything you hear has built-in definitions that you absorbed through experience. Enter cultural practices.

However, those built-in definitions and meaning can pose just as many problems as they solve. How aware is the person of their own history and what they’ve absorbed as normal behavior? How much self-ownership do they have concerning the meaning of any particular practice? Are they open to the practice having other meanings or purposes?

Remember, culture is a short-cut to meaning, a device for carrying entire narratives or stories tying together reality. If the weight of individual opinions is so heavy, and that’s just for a single person, imagine the exponential increase given to a story that has time/family attached to it.

Dialogue through Culture

To attempt addressing the very real difficulties, when considering a cultural practice, we can ask first what the purpose is. The person will provide a story. That story will give structure to the meaning the behavior has for them. It will be really easy now to immediately agree or disagree with the story, based on one’s own assumptions. Good conversation/dialogue is generative, it builds greater understanding. It isn’t warfare with two parties lobbing linguistic hand-grenades at each other.

Before engaging with the story, a full stop needs to happen. Use this space to reflect on:

1) identifying what shared Value the behavior is serving to support…2) identifying whether that shared Value holds the same level of importance for each of you in the context you’re in.

To keep it simple, let’s take the practice of washing one’s hands. The primary Value to be supported is likely going to be Cleanliness, but is such always primary in awareness? If you’re rushing to the bathroom in the middle of a movie that you spent far too much money to see in a theatre, is Cleanliness going to be the top concern or is Time-Management and Pleasure? If someone saw you not wash your hands and immediately began chastising you, claiming you clearly didn’t care about Cleanliness, your response would likely be anger/frustration. Why? Not because you got called out for not caring about something you do in fact care about, but because the other person clearly doesn’t care about Time-Management and Pleasure! See the irony? The other person cares about those things too, it just wasn’t their priority in that moment, precisely because they aren’t you.

Starting with Value allows us to get behind the stories/narratives that so easily catch us up in the moment. At that point, another person’s behavior no longer stands on its own, instead being caught by our own construction of reality and judged accordingly. Importantly, this isn’t, at this level, about morality, nor does it remove issues of ethics. We’re simply looking at having good generative dialogue. Frankly, if a chief concern is to convince another person the error of their ways, no better place exists to start than with what you have in common and an appreciation for your shared humanity.

Featured image: Photo by rosario janza on Unsplash

The post Culture as Reality Shaping appeared first on Life Weavings.

Don’t Forget the Humanity in Dialogue

Communication is more than words being exchanged between two or more people. It’s also more than the non-verbal physical cues made famous by such shows as “Lie to Me.” When people engage in dialogue, they’re seeking to build a relationship of perspective with reality and, if reality doesn’t fit quite well enough, get the other person(s) to agree regardless. This is true whether the discussion has to do with broad, socially significant, political opinions or the varied intimacies of one’s emotional state.

The significance of binding perspective to reality cannot be overstated. Opinions aren’t just mental states, they’re the means through which we gather the disparate pieces of reality and bind them to create an experience. That we all like to be right begins to make sense here, given the potential weight carried by our thoughts. Combine these two points and the many forms of communication can be seen in a new light.

We can start with cultural practices.

Culture as Reality-Shaping

Contrary to the majority of felt experience, our thoughts are rarely unique creations. They’re far more likely to be derivatives from our social upbringing and cultural backgrounds, to promotions of something we recently read and likely didn’t critique long enough. The latter is especially fun in conversation if confronted by someone who does immediately know more than we do, as our shallow understanding is highlighted. Did I say fun? I meant embarrassing.

The reason for the non-careful assumption inherent of many of our opinions depends on how critical you want to be about our humanity. For those with a more negative view, it’s due to our inherent laziness as thinkers. A more reasonable take has to do with time-management. It’s simply easier to assume that the information we personally encounter is more likely true than not. Taking the time to critically analyze everything that crosses our mental space is not only impossible (since a great deal is unconsciously taken in), but it’s really poor resource-management. We’re far too busy living our lives to halt at every thought.

Photo by twk tt on Unsplash

Photo by twk tt on UnsplashOne of those ways we’re living is through culture. Consider cultural practices as mental shortcuts to meaning. Ever had a word that you used but didn’t know if it was the right one? Or hear one that you didn’t know the definition of? Sure you could look it up on you smart phone, but that takes time. Better if everything you hear has built-in definitions that you absorbed through experience. Enter cultural practices.

However, those built-in definitions and meaning can pose just as many problems as they solve. How aware is the person of their own history and what they’ve absorbed as normal behavior? How much self-ownership do they have concerning the meaning of any particular practice? Are they open to the practice having other meanings or purposes?

Remember, culture is a short-cut to meaning, a device for carrying entire narratives or stories tying together reality. If the weight of individual opinions is so heavy, and that’s just for a single person, imagine the exponential increase given to a story that has time/family attached to it.

Dialogue through Culture

To attempt addressing the very real difficulties, when considering a cultural practice, we can ask first what the purpose is. The person will provide a story. That story will give structure to the meaning the behavior has for them. It will be really easy now to immediately agree or disagree with the story, based on one’s own assumptions. Good conversation/dialogue is generative, it builds greater understanding. It isn’t warfare with two parties lobbing linguistic hand-grenades at each other.

Before engaging with the story, a full stop needs to happen. Use this space to reflect on:

1) identifying what shared Value the behavior is serving to support…2) identifying whether that shared Value holds the same level of importance for each of you in the context you’re in.

To keep it simple, let’s take the practice of washing one’s hands. The primary Value to be supported is likely going to be Cleanliness, but is such always primary in awareness? If you’re rushing to the bathroom in the middle of a movie that you spent far too much money to see in a theatre, is Cleanliness going to be the top concern or is Time-Management and Pleasure? If someone saw you not wash your hands and immediately began chastising you, claiming you clearly didn’t care about Cleanliness, your response would likely be anger/frustration. Why? Not because you got called out for not caring about something you do in fact care about, but because the other person clearly doesn’t care about Time-Management and Pleasure! See the irony? The other person cares about those things too, it just wasn’t their priority in that moment, precisely because they aren’t you.

Starting with Value allows us to get behind the stories/narratives that so easily catch us up in the moment. At that point, another person’s behavior no longer stands on its own, instead being caught by our own construction of reality and judged accordingly. Importantly, this isn’t, at this level, about morality, nor does it remove issues of ethics. We’re simply looking at having good generative dialogue. Frankly, if a chief concern is to convince another person the error of their ways, no better place exists to start than with what you have in common and an appreciation for your shared humanity.

Featured image: Photo by rosario janza on Unsplash

The post Don’t Forget the Humanity in Dialogue appeared first on Life Weavings.

May 10, 2019

We Cannot Divorce People From Culture

Does the clothing make the person or the person make the clothing? While this question is typically related to dresses and women, the inquiry knows no gender. At the heart of the question is a consideration of the relationship between the created and the creator, between form and function. Clothing is not simply about covering the body, it functions dependent upon the intent of the person and the social context in which it is worn.

Follow along for a moment and we’ll get to the broader issue. In Western countries we notably wear black to funerals, brighter colors to weddings. The associations cannot be overstated, with one acknowledging an ending and the other a celebration of a type of birth or beginning. We have expectations of what to be worn at job interviews, on romantic dates, to music concerts depending on the genre. Importantly for the latter, location matters as well. Rock music played in an open stadium brings a certain dress-code, whereas the same music played in a concert hall by an orchestra will inspire a different response.

If anyone is shrugging at the significance of the impact of clothing choice, simply consider the days of High School and the social shame accompanying not wearing the ‘cool’ clothes, potential violence occurring if wearing shoes that are considered ‘must-have,’ and the time and mental anxiety accompanying what to wear for school pictures and first dances. For that matter, clothing stores have created an entire sales season out of ‘Back to School’ clothes shopping. Expand this a bit and consider wearing pastels or flowery-shirts to a funeral or ragged clothes and sandals to a job interview. Perhaps doing so was to make a statement, though it is precisely because the action is so contrary to expectations that the ‘statement’ will have any power (perhaps not great consequences though).

Culture Has Intrinsic Value

Clothing is simply one aspect of culture. Included in culture are a host of other issues that would not exist were there no human beings around to build and embody them in practice; religion, governmental systems, family structures, and social expectations at various levels. An initial focus on clothing helps us consider culture more broadly by 1) noting its intimate relationship to our humanity and 2) the impossibility of removing Value.

Any reflection on being human, collectively or individually, will inevitably involve memories associated with cultural practices. It is fair to say that to be conscious is to engage socially and one cannot engage socially without doing so through culture. Little wonder that the practices of culture have so much Value, they’re the means through which we initially inter-relate with one another.

Those building blocks for human relationships, the behavioral expectations and standards for interpersonal experience, are intimately tied to Values, even as they themselves are not such. Christianity is not a Value, nor is washing one’s hands after using the bathroom, wearing black at a funeral or democracy. What those practices support are Values; Spirituality, Cleanliness, Solidarity and Social Cohesion, respectively. We appreciate those Values and seek to support them because doing so is to align ourselves with one of the most basic of human needs: providing meaning/purpose.

Culture Has No Intrinsic Meaning

Photo by Tamara Menzi on Unsplash

Photo by Tamara Menzi on UnsplashIt’s impossible not to give some rationale for our behavior. When someone shrugs or declares “I don’t know,” the frustration felt is in no small part due to the bone-deep belief that a reason exists which must be found. Having a rationale for events is synonymous with ‘finding an answer’ or ‘solution.’ There’s a finality to it, despite, or even sometimes because of, the perceived ridiculousness of the story being told. The more absurd, the more the story is providing an answer regardless, i.e. the person is ‘crazy,’ ‘insane,’ ‘stupid’ or ‘evil.’ Such simple judgments pack the same punch as an involved story, they provide structure to the person’s experience.

What should be immediately apparent is the wide variation in our stories about behavior. Cultural practices are no exception. Religion may be the easiest example here, with group after group fighting, verbally and physically, over what is the ‘TRUE’ version of their particular mythology. Notice the Value doesn’t change, the need for Order/Spirituality remains constant. What the fight is over is the particular meaning to give to it. Does it drive behavior? Does it serve as a crutch? Does it provide a legitimate ground for morality?

When people of one group identify another as not being ‘TRUE,’ note that quite often the reasoning given is that the other simply doesn’t ‘understand’ properly. This focus on understanding as indicating legitimacy points us immediately back to the Value, but, and here’s the key, the Value as defined through the person criticizing. Cultural practices have no singular meaning because the story of their development for each person is as unique as each person’s genetic, familial and life histories. What’s often happening in debates of what is ‘TRUE’ religion (or any other cultural practice) are one’s own stories taking absolute ownership of a shared Value.

Cultural practices have no singular absolute meaning. They are derivatives of the human need to make meaning, not separate aspects of existence that people take on. To think of cultural practices as having inherent meaning is to divorce them from the humanity that gave them birth. Which is precisely where we all can contribute to a great deal of suffering.

Primacy of the Human

When considering a cultural practice, we can ask first what the purpose is for the person acting it out. They will provide a story that structures the meaning the behavior has for them. Before engaging with the story, a full stop needs to happen. This is to allow reflection on 1) identifying what shared Value the behavior is serving to support and 2) direct attention to how varied the other person’s personal history is from one’s own.

Identifying the shared Value can allow for an appreciation for why the person may deeply hold to the practice. Order, Social Cohesion, Family, and Cleanliness are nothing to easily dismiss, nor likely should they be. Once it is acknowledged how much weight the building of a story through a lifetime can bring to a Value, the strength of meaning/purpose becomes readily apparent.

We don’t have to agree with a particular practice, nor do we have to agree with the rationale given in support of it. However, if healthy dialogue is going to happen then we must first acknowledge that differences exist in those stories precisely because of the shared quality of being human.

Considering culture, we simply cannot lose sight of the human as a primary concern. To divorce or separate culture from the human being is to constrain humanity to a singular vision of what ‘should be.’ Such a divorce will drive the ‘war of ideas,’ a potentially fruitful dialogue exploring human expression, to simply ‘war.’

Featured image: Photo by Louis Hansel on Unsplash

The post We Cannot Divorce People From Culture appeared first on Life Weavings.

April 26, 2019

The Mighty Anecdote

Exploring the nature of ‘anecdotal evidence,’ why it’s so enticing and why we all engage in it. The power of the anecdote or story resides in what stories are: the creation of causal connections within our perception. We are declaring what we believe the world to be. That so many of our stories contain bias is also explored and noting why bias doesn’t mean there’s something wrong with our rationality or our minds.

Thankfully, questioning our stories doesn’t require us to act as if we’re cast adrift in a world without meaning and truth. What it does require of us is a willingness to accept the limits of perspective and to actively engage in more perspective-taking.

(A Universe of Perspective)

Podcasts can also be listened to on iTunes, Soundcloud, Libsyn, and Google Play.

For more information on “Humanity’s Values,” check out the main page.

Your support is deeply appreciated and allows me to keep bringing you more content:

The post The Mighty Anecdote appeared first on Life Weavings.

April 9, 2019

A Universe of Perspective

Stories are how we bind individual perception and social reality. Consider from a nautical metaphor, where stories are the lines connecting individual boats with the social pier. Sure, the boat exists but until it gets close enough to dock, the details of its make are uncertain and the quality of its captain is unclear. Without stories, nobody would have access to the inner worlds of others. Further, without them, the substance of who we are would be dismally small, cut off from the expanding presence of so many other perspectives. A dock without boats is a sad place.

Now, ‘stories’ are the narrative version of what we perceive with our senses. Think of a rock or tree. When they become ‘the rock struck me’ or ‘the tree fell over,’ we’re giving a structure to experience, providing ourselves an order to what otherwise would be a haphazard array of individual moments. It happens so seamlessly, attempting to think of experience as anything else is almost impossible. To help, consider a cartoon animation. There are many individual poses, incrementally streamed together into what we then see as movement. Much the same occurs in our brains and when we mentalize it through language, we get stories.

Weaving the World Together

This process of binding disparate pieces of reality to build the structure of our experience is why it’s so difficult to question our opinions. Further, it’s also why when our worldview is confronted, we often feel threatened or under attack. Perspective isn’t merely something we have, it’s the fundamental ground upon which we interact in and with the world. Coming back to the nautical metaphor, it’d be like someone removing and inspecting pieces of the hull from your boat as you come in to dock. Similar occurs when we question ourselves, ripping the floorboards out and letting in water. Talk about scary!

The binding process is automatic and unconscious for the vast majority of us in the majority of our lives. Ponder for a moment just where your thoughts come from, they arise without consideration fully formed and connected. Even attempting to think about your thinking requires the same process for those same thoughts are arising just as fully formed as the ones you’re attempting to contemplate! This can be amusing, but also frustrating and, when we police our thoughts from a desire to control them, is completely futile.

Photo by Natasha Brazil on Unsplash

This is where mindfulness practices can be helpful, not for control, but for being more aware of our thoughts/impulses at any given moment. Being ‘caught up’ in a thought/feeling is to fall victim to the notion that a singular story encompasses the whole of your experience. Mindfulness helps us identify the ‘thinker behind the thinking’ and recognize how much broader our potential is than any single thought/feeling can hold.

Reliance on the Personal

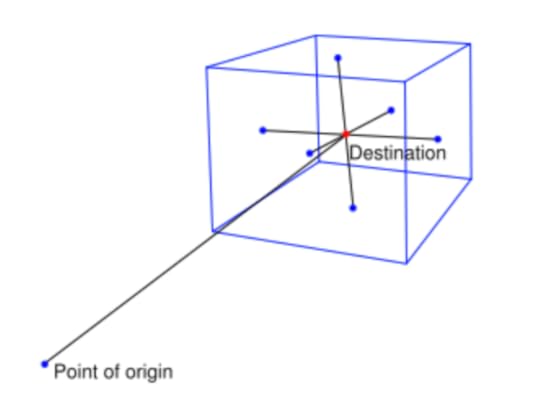

As we recognize no single story can hold the entirety of our own experience, so it becomes easy to see how no single story can hold the entirety of anyone else’s experience either. I’m reminded of the movie “Stargate” where movement through different galaxies is explained. You need six points of reference to identify a destination, but you also need a place of origin. That origin is individual perspective and the destination is the story cobbled together from several points within experience.

With such an image in mind and the power of interstellar travel firmly in our imagination, it is little wonder we all rely so heavily on personal stories or ‘anecdotes’ to structure what we believe to be true about ourselves and the world.

Importantly, “anecdotal evidence” does not simply mean “my own personal experience.” There is a causal connection being made between perception and what the world is or is supposed to be. Going back to “Stargate”, we don’t select disparate points haphazardly, but with the bedrock belief that in doing so we are defining a particular location in the universe. In other words, within the world of personal belief, there exists in the space between perspective and destination a sacred connecting line of ‘WHAT IS.’

We like our stories to be right, otherwise we wouldn’t be telling them, and they certainly feel right because having that feeling means we get to move forward in the world as if we know what’s going on. Thankfully, questioning our stories doesn’t require us to act as if we’re cast adrift in a world without meaning and truth. What it does require of us is a willingness to accept the limits of perspective and to actively engage in more perspective-taking. We may not be traveling amongst the stars, at least not yet, but our universe will still get a whole lot bigger and provide a greater potential for our lives.

The post A Universe of Perspective appeared first on Life Weavings.

March 24, 2019

Setting Goals within Your Values

Setting goals too often leads us into shame and self-doubt. I want to encourage you to possibly stop goal-setting for a moment and focus on what you care about. Start livable goals from a place of what you’re already doing, succeed from a place of plenty rather than wasting energy trying to leap from lack. We can help explore this by using the religious practices of Lent and dive into how Values never leave us.

Steps of Valued Living: (“Identifying Values” worksheet on Resources page)

Identify an area of your life you’d typically set a goal based on lack or self-denialWhat Value is associated with that area?Select 2-5 other Values that come to mind, or are associated with, that initial Value.What are healthy behaviors to support that Value?Consider how others are supporting those same Values and how you may bring such behavior completely or in part, to your own life.

The post Setting Goals within Your Values appeared first on Life Weavings.