Tracy Rittmueller's Blog, page 2

November 14, 2020

What monks, nuns and poets know about life balance

Some might think it a bit odd, even kooky, to live as a monk or nun devoted to daily prayer with a monastic community, or to be a poet spending unpaid hours creating odd little bits of writing known as poems. There’s no doubt the way monastics and poets spend much of their time is countercultural. But in a society characterized by extreme inequalities that produce poverty, violence, and diminished life expectancies, I’m convinced a movement in the opposite direction can only good.

Countercultural people and their practices are a counterweight to dominant powers and values. A counterculture can help straighten a skewed perspective. It might even help us achieve a more balanced rhythm of life. How we spend our days, is, as Annie Dillard wrote, “of course, how we spend our lives. What we do with this hour, and that one, is what we are doing.”

How is balance achieved?

Balance can be achieved by bringing together opposites to make a complete picture, a whole:

light and dark;

working and relaxing;

company and solitude;

feasting and fasting;

thinking and feeling;

laughing and weeping;

giving and receiving.

Balance can also be achieved through equal distribution of weight, emphasis, time, or value. Paddleboarders distribute their weight to keep from falling in. Proper distribution of weight in a vehicle ensures the balance required for safety in handling and braking.

A social scientist and an artist have imagined the possible innovations that might happen in scholarly thinking within a cross-disciplinary, balanced interface they call art-science, which places equal emphasis on the methods and contributions of both artists and scientists. “The art-science interface can provide a level playing field for stakeholders, encouraging participants to work more independently of the expectations and restrictions of their respective disciplines.”

The FCC’s Equal Time Rule was intended to balance the (possibly minority) opinion of those in control of media, specifically radio and television broadcasters. It regulated against restricting air time for their favored political candidate’s opponents, to prevent them from swaying an election.

In international politics, the theory of “the balance of power” which emerged during the Renaissance, may be based on a metaphor (balance) that can never work to accomplish lasting peace. In the late 1940’s, the poet Muriel Rukeyser argued peace isn’t possible when thought remains centered on power terms like force and surrender. These concepts create a reality in which the preparation for, the threat of, or the engagement in war is the focus of those in power. People at war inevitably commit atrocities that are should repel and outrage any thinking/feeling human. So why does any citizenry tolerate war? Dr. Bosmajian of the University of Washington in Seattle wrote in a 1984 paper for Christian Century, “To remove the moral obstacles to war, leaders, both political and religious, euphemize killing and the weapons of destruction and dehumanize the potential victims in order to justify their extermination.” Poetry can be a countercultural balance, working to straighten the twisted notion that force is the only viable resolution to conflict.

Poetry, T.S. Eliot wrote, effects a kind of fusion between what we feel and what we know to be true, so that “the feelings become elevated, intensified and dignified,” in a way that makes “truth more fully real to us.” The tools of poetry, then, might awaken our natural reverence for life and ignite repulsion against killing. Poetry might dignify the people we are tempted to classify as enemies, making us empathize with them enough that we would be as outraged by the senseless deaths of their children as we would be by the killing of our own. In this 1986 song, Sting imagines what could happen in war and peace “if the Russians love their children too.” Perhaps this lyric (poetry) influenced public sentiment in the last years of the 20th-century cold war:

The Benedictine motto “ora et labora” (prayer and work) is about balance.

Benedictine spirituality is rooted in a balance. Each day is to be lived with awareness of the fragility of life, making every single day precious. Therefore, the hours of each day are allocated so that everything needful for living may happen. There is time for prayer, study, work, meals, and healthy leisure or rest.

Benedictine monastics make time each day for prayer and work. They value each as necessary for fulfillment. In a Benedictine community, everyone participates in some kind of manual work–cooking, cleaning, gardening, painting, crafting, building, repairing, nursing–everyone is responsible for doing what they can to support the needs of the community for food, clothing, shelter, and care. Members whose primary work is scholarship will be assigned a turn at washing the dishes, and those whose daily work is housekeeping or maintenance will be granted time and solitude for Lectio Divina, or “spiritual reading.”

There is poetry in the phrase “ora et labora” in the rhyming of sound (ora) and in the word within a word. There is also a surprise. Ora is not exactly the same as the English prayer, (beseech, entreat, beg) but means mouth, to voice. Chant. Recite.

Benedict wanted monastics to train their tongues and voices, to use the power of words consciously and properly. To participate in the oral/aural chanting and communal recitation of psalms is to use the gift of words to worship like and with the angels.

In giving us the gift of language, the gift of words, God made us in the image of God. God said “Let there be Light,” and there was light. Therefore we, too, have the power to call things into being through our utterance — hatred or love, cruelty or kindness, despair or hope, war or peace.

Silence trains a monastic to refrain from the destructive misuse of words. Communal oral prayer trains the tongue to speak the truth of God. Imagine if all the children of God disciplined themselves to use the power of words with discernment and wisdom!

The skillful making of a poem requires an eye and an ear for balance

Writing poetry is work. The word itself comes from the Greek poietos, which means “made.” Making a poem is not unlike making a table or bowl, or even a cabin. It requires vision, tools, and skills. It requires an eye and an ear for balance.

A poem is crafted through a balance of inspiration and revision. Poets work for balance in their process and in their poems. A poem is experienced as more complete when it wholly stirs us, at emotional and intellectual levels, in heart and mind.

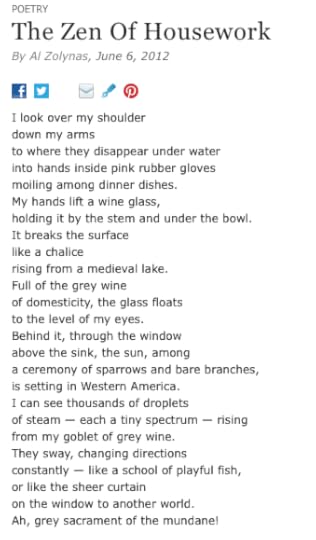

In my reading of poems, the most stirring of all are those that ground me in the mundane and open me to the transcendent. This kind of poem acts, as Al Zolynas poem says, “like the sheer curtain / on the window to another world.” Please click on this link to that poem, which has been one of my favorites since I first read it in the early 1990’s. Here is “Zen of Housework,” as published with permission in The San Diego Reader:

The Zen of Housework by Al Zolynas

What monks, nuns, and poets know about balance

The countercultural lives and practices of monastics and poets can help us gain balance, leading us into a more meaningful, purposeful, and peaceful daily way of life. Joan Chittister explains that by connecting the mundane to the sacred, by giving equal value to both the matter-of-fact and the transcendent experiences of life we begin to understand “It is all–manual labor and mystical meditation–one straight beam of light on the road to fullness of humanity. One activity without the other, prayer without the creative and compassionate potential of work or work without the transcending quality of prayer, lists heavily to the empty side of life.”

May we all be blessed with a balanced life and thereby experience the fullness of our humanity.

This is part 5 of the series 8 Things Poets and Monastics can teach us about Happiness with 8 poems to Make Life More Meaningful.

If you’d like to comment, ask questions, or receive email notifications of new posts, please use this form to email me. This is not a public comment form, and what you write will not be visible anywhere online. I will respond to you personally, and I promise not to inundate your inbox with advertisements. Instead, we’ll have a person-to-person email conversation.

[contact-form][contact-field label=”Name” type=”name” required=”1″ /][contact-field label=”Email” type=”email” required=”1″ /][contact-field label=”Website” type=”url” /][contact-field label=”Comment” type=”textarea” required=”1″ /][/contact-form]

Photo credit: christopherdale on VisualHunt.com / CC BY-NC-ND

November 4, 2020

What poets, monks and nuns know about silence

Poets live with silence:

the silence before the poem;

the silence when the poem comes;

the silence in between the words, as you

drink the words, watch them glide through your mind,

feel them slide down your throat

toward your heart ….

—Michael Shepherd, “Rumi’s Silence”

Silence, poetry and prayer have something in common—they connect us to the mysterious aspects of living. We can’t describe or explain mysteries. We can, however, experience them.

I first learned about the benefits of silence through a long association with poets. More recently after becoming a Benedictine oblate, I’ve gotten to know monks and nuns—collectively called monastics—who have deepened my understanding of the beauty and benefits of silence.

In the dark, it’s easier to see with peripheral vision than if we look directly at things. Since the experience of silence is inexplicable, I won’t attempt to describe what it does or how it benefits us. Instead I will give it a sideways glance, exploring its paradoxical attributes.

1. Silence is Paradoxical

Silence incorporates absence and presence.

It is common to think of silence as the lack of sound, but pure silence is something few of us ever experience. For me, silence is a place where distracting or disturbing noises will not disrupt the ability to concentrate, meditate, pray, rest, listen, dream or create. Silence, then, is that which is not there, an absence of noise.

Silence is a state of being that creative or meditative people seek because it allows them, as poet Jane Hirschfeld writes, to “flush from the deep thickets of the self some thought, feeling, comprehension, question, music, [they] didn’t know was in [them], or in the world.”

This work of “flushing,” as every hunter, photographer, poet and spiritual seeker knows, requires that we remain quiet. If we charge heedless through woods or words, talking out loud or preoccupied with worries and plans, whatever we’re after will hunker down and hide. To flush out that of which we’re not aware, we must master our impulsive instincts, quiet our relentless egos, and relinquish our desire to make something happen. This is simple yet difficult work. We wait for some thing to change position and emerge, allowing us to discover its presence.

Silence is therefore a place, in the presence of attentive awareness, where we discover a hidden presence.

Silence begins in separation but leads to encounter.

Silence requires our physical and/or emotional withdrawal from others, a separation we often call solitude. It is worth noticing that in the ancient Genesis story, God’s making of the world involved separating the light from the darkness, the waters below from the sky above, the dry land from the sea. Here we see the act of separating as engendering the act of creating.

Separation makes distinctions. Without the acquired ability to separate sequential sounds into individual words, a foreign language becomes nothing more than a stream of unintelligible noises. Minuscule silences, and the ability to hear them, are necessary for the discernment of words. On the other hand, true silence is the absence of language.

Many people spend much of their lives avoiding silence because when we are divided from the comfort of a friendly, amusing or diverting voice, we inevitably will encounter the unavoidable, perpetual problem of loneliness. In his book The Restless Heart Ronald Rollheiser names the forms that loneliness takes: alienation; restlessness; fantasy; rootlessness; and psychological depression.

Silence intensifies the beatings, stirrings and yearnings of our lonely hearts, turning them loud, palpable and painful. Mr. Rollheiser believes that if we allow loneliness to remain hidden, it will ambush us, wreaking havoc. To encounter and name our loneliness, however, is to bring it into focus so we can integrate it into our lives in meaningful ways, enabling psychological and spiritual growth. Then, after we have begun that work of integration, silence will often become a refuge of tranquility, a place where we can experience peace.

In silence we can also encounter God, which brings us to the next paradox:

Silence is both perceptible and spiritual.

In silence, we might notice rustlings and whispers that would be masked by noise: external voices and our own internal yammering; machines and devices; the roar of traffic and crowds. Silence opens doors to insight. We might sense the yearnings of our lonely hearts or feel the palpable presence of peace. The Benedictine attitude toward silence is, appropriately, one of reverence.

Christine Valters Paintner writes, “When we show reverence, we recognize a presence much more expansive than ourselves.” Reverence opens us to listening for that which is transcendent and spiritual, beyond the range of our physical perceptions.

Here’s an old, old story that begins with the perceptible experiences of noise followed by silence, then leads us to a transcendent experience of the Divine:

Elijah, a prophet of God, was standing on a mountain searching for God when a mighty wind arose, strong enough to split the mountain and cause an avalanche of rocks, but God was not in the wind. Them came an earthquake, and after that a fire. God was in not in those great forces either. Imagine the catastrophic din of a tornado followed by an earthquake followed by a fire. Elijah wisely hid in a cave. Think about the hush after all that—the sound of utter silence. It was then that Elijah heard a gentle whisper, a voice calling him by name (1 Kings 19:11-13).

Isn’t this whisper an image of the profound fulfillment of that which we all desire? Whether after devastation or after the ordinary disappointments of a routine day, we crave the gentle voice of someone who knows us, who calls us by name. We want to draw near to the One who intimately loves us.

It’s an ancient story with timeless appeal. So, where on earth today is that holy mountain, the place where we might seek the Divine? Joan Chittister, OSB (Order of St. Benedict) says God is where we are. We don’t need to journey to holy mountains or take difficult pilgrimages to find God. Although shrines and devotions may provide occasional, important life experiences, and although they can be touchstones that help solidify our faith, we are able to have deeply spiritual lives without them. We need only develop, through spiritual practices, “the consciousness of God at all times and in all places.”

2. Silence strengthens Words’ Power.

Poets taught me the careful, “close” reading of poems. Benedictines taught me the similar practice of lectio divina, a meditative reading of spiritual texts. As a poet and a Benedictine Oblate, I have experienced that the careful reading of words serves to make me more conscious of the things in consciousness and in life that are present, but veiled.

At the intersection of text and white space is the close reading of poetry. It is a practice that opens our understanding to the nuances and resonances of language, and to the power of words to contain hidden and multiple associations. The close reading of a poem helps us be attentive to what is, as well as what isn’t, being said.

At the intersection of word and silence is the practice of Lectio divina. Through spiritual reading, we embodied humans–complicated creatures with our physical senses, intellect, and emotions–learn to wait for the transcendent voice of God to emerge “from the words and shimmer within [us]” (Christine Valters Paintner, Lectio Divina — the Sacred Art, 64).

If you google lectio divina, you’ll find many descriptions of this practice. Here is one of the most beautiful:

“The first movement of lectio divina [is] ‘reading’ But this kind of reading is so much more than simply reading words, stringing together sounds, and comprehending the meaning of those sounds. Rather, [it] is an entry to awakening your body, mind, and heart to God’s presence, listening for God’s voice not merely on the surface of the words and phrases, but between them, around them, and deeply within them. In Jewish tradition there is the belief that Torah is black fire on white fire. As Rabbi Avi Weiss writes, ‘The black letters represent thoughts which are intellectual in nature…..The white spaces, on the other hand, represent that which goes beyond the world of the intellect. The black letters are limited, limiting and fixed. The white spaces catapult us into the realm of the limitless and the every-changing, ever-growing. They are the story, the song, the silence’” (Lectio Divina– the Sacred Art, 63-64).

3. Silence adds meaning and peace to our lives.

Silence is both absence and presence, paradoxically a place of separation and encounter, a sensory experience that can lead to transcendence. Silence can be full of thought and at the same time empty, the white space between and surrounding a thoughtful life.

Poets and monastics have taught me that silence helps attune my heart to better listen to what is present in me, as well as to what is present in others and in the world. Silence also helps me be aware of the immanent presence of the Divine in my life. Awareness —reverent listening—grows when I take time and create space in my life to live with, and in, a healthy measure of solitude and silence. The practice of silence adds meaning and peace to our lives.

4. Make room in your life for silence.

Silence, like poetry, prayer, or anything that moves us into an encounter with mystery, can’t be understood through reading about it. To know silence, we must experience it. Here are suggestions to help you experience silence.

Start small — this article offers six simple ways to invite silence into your life.

Talk less. Cultivate restraint of speech. In her book How to Live: What the Rule of St. Benedict Teaches Us About Happiness, Meaning, and Community, Judith Valente suggests that before speaking, we might pause and apply the standard “is it true, is it good, is it kind?” We can learn to hold back words “out of esteem for silence.”

Turn off background noise and shush your devices. If you find it excruciating to unplug you might ease into it by turning down the volume and making your devices quieter.

Reduce the static in your life by learning to say no.

Occasionally step back from social media for a day or a season.

Pray and meditate — it’s a profound way to experience silence not as a goal, but as a path to a good life.

Ultimately, silence will have its most enduring and beneficial effects if we develop a regular practice. Practices–for yogis, poets, artists, scientists, musicians and athletes–are simply formalized habits. By committing something to a schedule, by faithfully doing that thing, we make it into a practice.

This is part 4 of the series 8 Things Poets and Monastics can teach us about Happiness with 8 poems to Make Life More Meaningful.

If you’d like to comment, ask questions, or receive email notifications of new posts, please use this form to email me. This is not a public comment form, and what you write will not be visible anywhere online. I will respond to you personally, and I promise not to inundate your inbox with advertisements. Instead, we’ll have a person-to-person email conversation.

[contact-form][contact-field label=”Name” type=”name” required=”true” /][contact-field label=”Email” type=”email” required=”true” /][contact-field label=”Website” type=”url” /][contact-field label=”Message” type=”textarea” /][/contact-form]

October 26, 2020

61 Free Resources to support your mindful self-compassion practice

To skip my reflection on my own mindful self-compassion journey, and get right to the 61 free resources to support your mindful self-compassion practice , click here.

Mindful Self-Compassion is not a Self-Improvement Project

Opening her presentation on “Benedictine Spirituality and Self Compassion” in the spring of 2017, my friend and fellow Benedictine Oblate Becky Van Ness, OblSB smilingly admonished us not to treat the learning of self compassion as if it were another project in self improvement.

My response was laughter. Humor enables me to sidle up to my glaring weakness. Ha-ha, yes, that’s me all right.

“I have a compulsion for self-improvement,” I’ll admit.

Those who know me nod vigorously. Yes.

“But I’m working on it.”

This cracks people up. But I’m only half jesting. My conundrum is real. How can I grow if I don’t try?

Since beginning my journey as an Oblate, I have been reading The Rule of Benedict daily, often accompanied by Joan Chittister’s commentary. Not long after I became an Oblate candidate, I read this sentence, but only one word stood out to me then:

“Benedictine spirituality is clearly rooted in living ordinary life with EXTRAORDINARY awareness and commitment.”

Hi. I’m Tracy and I’m a perfectionist.

These days, after years of study and daily contemplative practices, after monthly Oblate group meetings and growing into my community, I see that sentence differently:

“Benedictine spirituality is clearly rooted in living ORDINARY life with extraordinary AWARENESS and COMMITMENT.”

And I’m not even trying to see differently.

Spiritual Practices lead to growth the way soil, nutrients, warmth, light, and water work together to transform a seed into a sapling into a tree.

Five years ago I learned that my husband — my best friend and soul mate — suffers from progressive cognitive impairment caused by non-Alzheimer dementia. I was hurled into a desperate grief that left me so hurting and confused I could barely function. Looking back, wondering how I had moved from that dark, dark place into today, where my life is full of serenity and joy, I discovered 3 attitudes that support self-compassion.

3 simple attitudes to support self-compassion

#1 — Practice Playfully

#2 — Aim for “More Often than Not”

#3 — Make a Specific Commitment to Practice Mindful Self-Compassion

the Gentle Way to practice mindful self-compassion

Allocate 15-30 minutes once a week to educate yourself and begin practicing self-compassion.

Don’t let perfectionism ruin this for you. If you manage to keep your commitment to practice mindful self-compassion “more often than not,” re-mind yourself you’re doing very well.

Don’t work or strive; instead allow your practices of mindful self-compassion to grow you the way soil, nutrients, warmth, light, and water work together, in time, to transform a seed into a sapling into a tree.

Here are 61 Free Resources to support your mindful self-compassion practice

Visit Self-Compassion.Org

Dr. Kristin Neff’s “Home” and “About” pages will quickly introduce you to mindful self-compassion. Start with those, and read her “tips for practice.”

Then do one of her 8 exerices or listen to one of her 10 guided meditations. Her site tells how long each meditation lasts–a helpful feature.

Her “Resources” page has links to 26 websites to help you learn more about this transformative self-care practice.

Vist ChrisGermer.com

Chris Germer, PhD is a clinical psychologist and lecturer on psychiatry (part-time) at Harvard Medical School. He co-developed the Mindful Self-Compassion (MSC) program with Kristin Neff in 2010. This link will take you to a page of 7 audio mindful self-compassion meditations with written instructions for practicing, along with 14 more informal mindful self-compassion meditations.

Try this 30-minute Body Scan Meditation by Jon Kabat-Zinn

May you be mindful,

may you be compassionate,

and may you respond to your own suffering

as you would care for a dear friend.

October 25, 2020

How poetic and monastic practices empower a vibrant, sacred way of life

Do you want to explore the mysterious, wild regions of living a vibrant, sacred way of life?

Maybe you feel called to be an artist—potter, painter, dancer, musician, poet, crafter, or doodler. Perhaps you want to associate with people who will help you grow in wisdom, because you’re seeking courage to devote yourself to the service of Love.

If the words authenticity, connection, consciousness, peace, and gratitude speak to the mystical core of silence and solitude within you, I invite you to ask, “How?”

Ask not what can I do? Ask how can I be?

The question, How? is a much more challenging one than the obvious, and frequently only, question people in search of a beautiful, meaningful life ask:

“What can I do?”

What focuses on programs, strategies, and measurable outcomes. How, the way I’m asking it, is concerned with presence, with becoming people whose way of life and way of interacting with each other embodies our values. What is oriented toward product and productivity. How opens the heart, mind, body, and energy/spirit to relationships, to creating meaningful, authentic connection, to learning to be trustworthy and trusting.

on the inner contemplative mystic: poetic and monastic practices

Welcome to my blog. In the spirit of Benedictine hospitality, I honor the essential dignity and rare beauty of you. I invite you to explore, with me, how to become more vibrantly, wholly, hope-fully alive.

In this place, I write about how the communities and practices of poets and monastics empower a vibrant, sacred way of life. I’m Tracy Rittmueller, a poet/writer who works in community & organizational development to promote peace and justice through the arts. I’m also a Benedictine Oblate, which means I am associated with and committed to the Sisters of Saint Benedict’s Monastery (in St. Joseph, Minnesota), but I live outside the monastery, at home with my husband. I am a mother (two sons), a grandmother (two granddaughters) and spousal caregiver, accompanying the love of my life on his journey with non Alzheimer, dementia-related cognitive impairment.

Theologian and contemplative scholar Beverly Lanzetta writes that all humans have, deep in their beings, a spark of “the monk within,” an archetypal inner contemplative mystic in search of a sacred way of life. My awakening to a contemplative orientation to daily life manifests in the practices of poetry and monasticism. Whenever I feel most ecstatically at home — surrounded by the loving acceptance of like-minded, kind-hearted people—I find myself among people who are, or who value, poets and/or monastics.

By following that nudge to explore, and deepen, a sacred way of life, I have learned that the serenity of peace can be the bass notes to the soundtrack of my life’s challenging and beautiful days. In this place—this blog called The Poetry of Transformation—I share my thoughts about how the overlapping practices of poetry and monasticism empower a vibrant, sacred way of life.

on hospitality and the flow of electromagnetic love

In one of my lifelong favorite poems, “The Signature of All Things,” Kenneth Rexroth wrote, “The saints saw the world as streaming / in the electrolysis of love.” As I approach my 60th year, I am learning to embrace the duties of a spousal caregiver by surrendering to the streaming flow love, in the playful spirit of improvisation. That means I don’t have a regular schedule of posting on this blog. I might add something new once or twice a month, possibly less frequently.

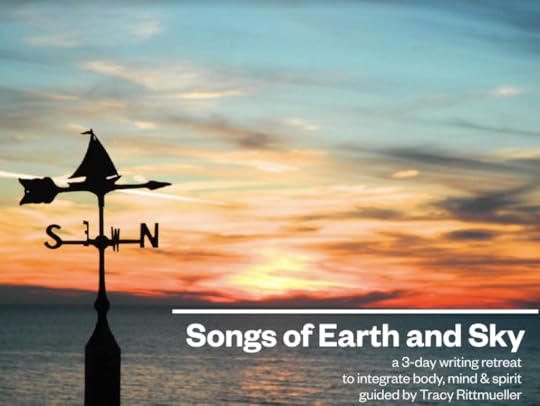

Meanwhile, if you’d like to get make some time for yourself to surrender to the streaming flow of love, I’ll send you a free copy of my e-book Songs of Earth and Sky: a 3-day writing retreat to integrate body, mind & spirit.

This guided retreat developed spontaneously in the summer of 2020, when a young friend of mine, living alone in Korea during COVID-19 restrictions, asked whether I had any ideas for a writing retreat. The book provides some helpful practices for getting to know your own inner poet/monk/contemplative mystic, and gives you a sample of how a vibrant, sacred way of life can feel.

Click on the book’s cover image below, to read a little bit more about the book and download your copy. And may you en-joy the journey!

Click here to download Songs of Earth And Sky

Click here to download Songs of Earth And Sky

8 Things poets and monastics know about the power of words

About words….

We think we know what words are—the spoken sounds and written letters we combine to form sentences to convey what we mean. Words carry on conversations, broadcast news, spread rumors, make promises, utter threats, express complex emotions, form ideals, formulate questions, make peace, build a better world, destroy reputations, crush hope, and declare war. Words are powerful.

Poets and monastics are word-centered people.

Poets use words as tools for art making. They understand the complexity and multi-layered power of words to arouse human consciousness and creativity.

Spiritual seekers of all traditions, including Benedictine monastics, mine spiritual writings for the illuminating wisdom that transcends time and cultures. In these writings, they discover the mysterious power of words to connect physical, visible elements of creation with invisible, spiritual realities. In other words, they experience how words make us whole-y.

8 things poets and monastics know about the power of words

1. Words enable consciousness—

Consider the story of the child Helen Keller’s awakening consciousness when her tutor, Annie Sullivan, led her to connect the spelled word-symbol w-a-t-e-r to the actual cold liquid something spilling from the well pump, filling the pitcher, splashing and cooling her skin. Describing this scene in her biography, Ms. Keller wrote:

“As the cool stream gushed over one hand she spelled into the other the word water, first slowly, then rapidly. I stood still, my whole attention fixed upon the motions of her fingers. Suddenly I felt a misty consciousness as of something forgotten–-a thrill of returning thought; and somehow the mystery of language was revealed to me. I knew then that ‘w-a-t-e-r’ meant the wonderful cool something that was flowing over my hand. That living word awakened my soul, gave it light, hope, joy, set it free! There were barriers still, it is true, but barriers that could in time be swept away.”

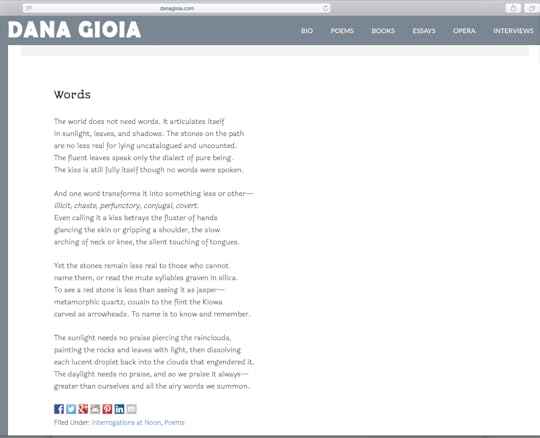

And here is Dana Gioia’s poem “Word” which speaks to the human need for words, which are the facilitators of human knowledge and human memory.

If it is true that words are makers of consciousness—and I believe it is true—then to allow our understanding of words to remain spiritless and superficial is to remain in a listless state of semi-consciousness.

2. Words enable compassion—

in a review of Sarah Smarsh’s Heartland: a Memoir of Working Hard and Being Broke in the Richest Country on Earth, Gracy Olmstead explains how books like this—stories of human experience told in in words carefully chosen and skillfully ordered—have the inherent power to change a culture. Words can be keys to locked entrances, opening eyes of people blind to injustice, opening hearts of people indifferent to caring. Words, in other words, can create transformative vision. They can enable the kind of compassion that insists on finding a better, more peaceful and just, way to confront problems.

3. The ability to communicate through words makes us human + 4 more reasons words matter

Gracy Olmstead is a thoughtful journalist who wrote, “Any monkey can take a picture with a smartphone. Point and click. But the ability to encapsulate a moment in nouns and verbs, adjectives and adverbs – only a human can do that.” Here’s a bullet-point list of her reasoning.:

#4. Words give expression

#5. Word give us the full story: its context background, beginning, and ending.

#6. Words connect us to the other.

#7. Words awaken our imagination.

Note that Ms. Olmstead writes in response to a recent article by Ali Eteraz, who claims that we are probably living in a post-literate, image-centric society “where the ability to communicate doesn’t require anything more than rudimentary reading and writing…sounds and pictures can do the job just as well…perhaps better.” This rebuttal shoots down the premise that images can communicate “just as well [and] perhaps better” than words.

If you want to ponder what words contribute to our world and the our lives, take fifteen minutes to read The War on Wordsmiths by Ali Eteraz and 5 Reasons Why Words Matter by Gracy Olmstead.

8. Utlimately, words manifest the being of all creation

Hildegard of Bingen was an 11th Century Benedictine whose art, music, writings, and poetry are repositories of consciousness, compassion, and ageless wisdom. In the introduction to her Meditations with Hildegard of Bingen, Gabriele Uhlein writes of Hildegard’s conception of “veriditas” — the verdancy, the “greening” power of God, as the “vital force that embraces creation and the “pattern for all good” (p 17).

On page 49, Ms. Uhlein’s translation of Hildegard’s writing links the concept of veriditas, the “greening,” creative power, directly to “the WORD”…

God’s WORD is in all creation,

visible and invisible….

…

This WORD manifests in every creature.

Now this is how the spirit is in the

flesh–the WORD is indivisible from GOD.

The creative / greening power of the word, from the book “Meditations with Hildegard of Bingen” by Gabriele Uhlein.

The creative / greening power of the word, from the book “Meditations with Hildegard of Bingen” by Gabriele Uhlein.

This is the mystery inherent in the creation story of Genesis, in which God speaks the world into being, establishing the word as the life force of all creation. The fall of creation, instigated by humanity’s loss of innocence through the knowledge of good and evil, introduced the power of destruction, of decay and death. This is when the word also assumed dualistic power. As Nobel Laureate Heinrich Böll famously said, “Words kill; words heal.” (Worte toten; Worte heilen.)

Words matter; we should choose to use words wisely

Through an inherent power to invoke consciousness, awaken compassion, contain knowledge and memory, and embody humaneness, words create being. Words have power—to heal, restore, and renew, but also to wound, destroy and kill.

The poets and monastics who respect and reverence words, do so with an intention to understand and handle word-power so the effect of their words in the world will be beneficial.

Let not our words desensitize, be hurtful, be cruel, or grind our humanity down to the lowest common denominator of our animalistic instincts. Instead,

May our words awaken, empower, and advance what is most noble in us and what is most lovely and praiseworthy in the world.

The next article in this series explores how the cultivation of silence facilitates our comprehension of the immense power of words, and aids our acquisition of the self-restraint that limits the harm our thoughtless, careless, spiteful, or malicious words can cause.

October 24, 2020

How poetic and monastic practices empower a vibrant, sacred way of life

Do you want to explore the mysterious, wild regions of living a vibrant, sacred way of life?

Maybe you feel called to be an artist—potter, painter, dancer, musician, poet, crafter, or doodler. Perhaps you want to associate with people who will help you grow in wisdom, because you’re seeking courage to devote yourself to the service of Love.

If the words authenticity, connection, consciousness, peace, and gratitude speak to the mystical core of silence and solitude within you, I invite you to ask, “How?”

Ask not what can I do? Ask how can I be?

The question, How? is a much more challenging one than the obvious, and frequently only, question people in search of a beautiful, meaningful life ask:

“What can I do?”

What focuses on programs, strategies, and measurable outcomes. How, the way I’m asking it, is concerned with presence, with becoming people whose way of life and way of interacting with each other embodies our values. What is oriented toward product and productivity. How opens the heart, mind, body, and energy/spirit to relationships, to creating meaningful, authentic connection, to learning to be trustworthy and trusting.

on the inner contemplative mystic: poetic and monastic practices

Welcome to my blog. In the spirit of Benedictine hospitality, I honor the essential dignity and rare beauty of you. I invite you to explore, with me, how to become more vibrantly, wholly, hope-fully alive.

In this place, I write about how the communities and practices of poets and monastics empower a vibrant, sacred way of life. I’m Tracy Rittmueller, a poet/writer who works in community & organizational development to promote peace and justice through the arts. I’m also a Benedictine Oblate, which means I am associated with and committed to the Sisters of Saint Benedict’s Monastery (in St. Joseph, Minnesota), but I live outside the monastery, at home with my husband. I am a mother (two sons), a grandmother (two granddaughters) and spousal caregiver, accompanying the love of my life on his journey with non Alzheimer, dementia-related cognitive impairment.

Theologian and contemplative scholar Beverly Lanzetta writes that all humans have, deep in their beings, a spark of “the monk within,” an archetypal inner contemplative mystic in search of a sacred way of life. My awakening to a contemplative orientation to daily life manifests in the practices of poetry and monasticism. Whenever I feel most ecstatically at home — surrounded by the loving acceptance of like-minded, kind-hearted people—I find myself among people who are, or who value, poets and/or monastics.

By following that nudge to explore, and deepen, a sacred way of life, I have learned that the serenity of peace can be the bass notes to the soundtrack of my life’s challenging and beautiful days. In this place—this blog called The Poetry of Transformation—I share my thoughts about how the overlapping practices of poetry and monasticism empower a vibrant, sacred way of life.

on hospitality and the flow of electromagnetic love

In one of my lifelong favorite poems, “The Signature of All Things,” Kenneth Rexroth wrote, “The saints saw the world as streaming / in the electrolysis of love.” As I approach my 60th year, I am learning to embrace the duties of a spousal caregiver by surrendering to the streaming flow love, in the playful spirit of improvisation. That means I don’t have a regular schedule of posting on this blog. If you’d like to know when I’ve published a new reflection, meditation, poem, or “how to,” you can sign up here to receive email notifications. You’ll probably get an email once or twice a month, possibly less frequently.

When you sign up, I’ll send you a free copy of my e-book Songs of Earth and Sky: a 3-day writing retreat to integrate body, mind & spirit. The book developed spontaneously in the summer of 2020, when a young friend of mine, living alone in Korea during COVID-19 restrictions, asked whether I had any ideas for a writing retreat. The book provides some guidance for getting to know your own inner poet/monk/contemplative mystic, and gives you a sample of how a vibrant, sacred way of life can feel.

May you en-joy the journey!

October 20, 2020

For Greater Serenity, Practice Playfully

I’m trying to see life more playfully, from a child’s point of view. For the reward of necessary joy, I’m ready to turn my adult-y, logical way of knowing how upside down.

Sometimes adult life feels inelegant, unmanageable and hard. There is sickness, suffering and death. There are fractured relationships we can’t repair. The international, national and local news can be heartbreaking—divisive, ugly, violent. To counter your feelings of helplessness and sorrow, watch a child at play.

I love to watch my six-year-old granddaughter cartwheeling. Her joy is so effervescent, it’s contagious.

She sprints across the newly greened spring lawn then leaps into a lunge. Her palms press the earth, legs extending to the sky. She rotates and lands confidently upright, making this amazing feat appear effortless. But her first cartwheels were disasters. She performed dozens, possibly hundreds, of clumsy ones. In time, her relentless practice strengthened her upper body. Her balance, flexibility and technique improved.

We could turn this into a lesson about patience, how practice leads to perfection. But when steeped in the reality that we are powerless to change so much of what is painful in life, we don’t need another pep talk to motivate self-improvement, or a manual outlining the steps to a successful life. What we need is our inner child’s pure, authentic joy, found in the delight of play–running, tumbling, rolling down the hill, or turning cartwheels.

When my granddaughter was learning cartwheels, she was awkward, stumbling, falling on her backside. Yet even in her “failures,” her delight was infectious. She was not judging herself. She was simply, playfully turning cartwheels.

If you love cartwheels, that’s what you do, over and over, not because you have to, not because you’re trying to win an Olympic medal, but because living in your wonderful body, moving and discovering its strength, is delightful. Your body is your life, your breath, your blood, your vitality. And so you cartwheel.

In the poetry of transformation, we aim our whole lives toward hope and love. We know that mindful practices and whole-life healthy habits will grow us. We can approach our growth dutifully, taking everything on as a project in self-improvement. Or we can throw ourselves into our journey the way a child learns to walk, run, or cartwheel–playfully and without self-judgement.

Joy is necessary. How wonderful, that all it takes to imbue our daily lives with delight, is to remember, and nurture the life of the child within us.

October 15, 2020

3 things nuns, monks and poets know about why you should “keep death daily before your eyes”

For the next year or so, I will be studying Michael Casey’s Seventy-four Tools for Good Living: reflections on the fourth chapter of Benedict’s Rule with my oblate group at Saint Benedict’s monastery. Among those seventy-four tools is this one:

“To have death present before one’s eyes every day.” (RB 4:47)

And this is a tool for good living???

That we should think daily about the imminent death of everyone we know and our own mortality may seem counter-intuitive. How can the constant awareness of death make our lives happier? But monastics are not the only people who live consciously with the awareness of death; this is something poets also embrace. Much poetry and tribute is motivated by the awareness of death.

After the poet Donald Hall died last summer, I wrote a small tribute about the influences his words, his being, and his loving relationship with one of my very favorite poets, his wife Jane Kenyon, have had on my life. His early 1970’s essay Goatfoot. Milktongue. Twinbird. was the first critical essay on the craft of poetry I ever read, and it solidified my longing to become a poet.

Recently I discovered Donald Hall’s essay The Poetry of Death (The New Yorker, Sept. 12, 2017), in which he writes about the poetic impulse toward elegy. Elegy, he believes, was the first poetry. He concludes by describing the conjugal unity of voice he found with Jane only after her death, in the “necropoetics of grief and love in the singular absence of the flesh.”

(The Urban Dictionary defines necropoetics as “Writing poems or songs about dead people, death, and dying; feeling that your songs or poem was inspired by someone dead or dying.”)

In his 2017 essay, Mr. Hall refers readers to numerous poems exploring death, grief and love, including Walt Whitman’s matchless lament, which he wrote following the death of Lincoln, “When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d.” Rereading this poem and contemplating the Rule of Benedict 4:47, I identified 3 things nuns, monks and poets know about why we should keep death always before our eyes.

1. The knowledge of death reminds us life is fragile.

Jeff Greenberg is a psychologist who studies how people respond to events that force us to confront our mortality. What do we think when we hear news of terrorist attacks, mass shootings, wildfires and earthquakes, or a car accident that kills three generations of a family?

“Greenberg says studies have shown that most of us find ways to discount the possibility that the thing on the screen could happen to us — big and small reasons why we in particular are safe.” We tend to think about our own death as abstractly far away in the future, in terms of, “Not me; not now.”

Not so, say monastics and poets. Life is fragile, so relish every moment of it.

Have you not seen, Soul, how the brightest and most precious things of earth end?

If death treats earth’s splendor so, who can resist it?

That same death has his arrow directed at you.

These are the words of Duke of Gandia in 1539, better known as St. Francis de Borja. The monks of St. Benedict’s Abbey in Kansas explain that after being obliged to view the decaying remains of the once beautiful Empress Isabella (to verify her death), he came to the realization that the fragility of life demands we live every day, every moment, with the awareness of immanent death. This awareness changed his priorities, and his life.

Donald Hall begins “The Poetry of Death” this way:

Jane Kenyon and I almost avoided marriage because her widowhood would have been so long, between us was there such a radical difference in age. And yet today it is twenty-two years since she died, of leukemia, at forty-seven—and I approach ninety.

We never know, he indicates, when death will come to us or to our loved ones. To detach ourselves from the reality of death is to live unconsciously. This dulling of the mind makes us forget what is important in life, all the invisible, non-pressing, unscheduled things that make our living matter–joy, peace, kindness, attentiveness, love. Poets and monastics understand that the knowledge of death helps us keep our priorities in right order.

2. The knowledge of death changes the way we think and live.

Benedict knew that the knowledge of death motivates us to live differently, without complacency, wide awake with eyes open and hearts softened. Here are words from the prologue of the Rule of Benedict (translation by Joan Chittister, OSB):

Let us get up then, at long last, for the Scriptures rout us when they say, “It is high time for us to arise from sleep” (Rom. 13:11). Let us open our eyes to the light that comes from God, and our ears to the voice from the heavens that every day calls out this charge: “If you hear God’s voice today, do not harden your hearts” (Ps. 95:8). And again: “You that have ears to hear, listen to what the Spirit says to the churches” (Rev. 2:7). And what does the Spirit say? “Come and listen to me; I will teach you to reverence god” (Ps. 34:12). “Run while you have the light of life, that the darkness of death may not overtake you” (John 12:35).

The writing of poetry, too, awakens us, says Jane Hirschfield:

Poetry is a release of something previously unknown into the visible…Poetry magnetizes both depth and the possible. It offers widening of aperture and increase of reach. We live so often in a damped-down condition, obscured from ourselves and others. The sequesters are social—convention, politeness—and personal: timidity, self-fear or self-blindness, fatigue. To step into a poem is to agree to risk. Writing takes down all protections, to see what steps forward.

Although he doesn’t state it directly, Donald Hall’s entire essay on the poetry of death (which arguable could also be called the poetry of life) indicates that he lived much of his life—purposefully, deliberately outside the rushing, consumer culture of our era, setting his own priorities and not letting institutional or societal expectations dictate how he scheduled his days–because of an acute awareness of death. Encountering death (after the numbing stages of grief subside) causes us to participate in life more perceptively–with all of our senses open. This is from Walt Whitman’s long elegy for Lincoln, When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d:

Then with the knowledge of death as walking one side of me,

And the thought of death close-walking the other side of me,

And I in the middle as with companions, and as holding the hands of companions,

I fled forth to the hiding receiving night that talks not,

Down to the shores of the water, the path by the swamp in the dimness,

To the solemn shadowy cedars and ghostly pines so still.

And the singer so shy to the rest receiv’d me,

The gray-brown bird I know receiv’d us comrades three,

And he sang the carol of death, and a verse for him I love.

From deep secluded recesses,

From the fragrant cedars and the ghostly pines so still,

Came the carol of the bird.

And the charm of the carol rapt me,

As I held as if by their hands my comrades in the night,

And the voice of my spirit tallied the song of the bird.

The knowledge of death alters our perceptions so that we see the solemnity in tress, hear the mystery in birdsong more raptly, and (as Whitman shows later in his poem), become inherently more capable of experiencing wonder and responding in praise:

Prais’d be the fathomless universe,

For life and joy, and for objects and knowledge curious,

And for love, sweet love—but praise! praise! praise!

3. The knowledge of death mysteriously heightens and intensifies our capacity for joy.

How it works, I cannot explain, but it is true that when we know death and the possibility of loss, the magnitude of our joy increases. Writing for On Being, Omid Safi describes waking up after a night in the hospital, surrounded by family and nurses all praying for him because, when he had been admitted the evening before, it had been highly likely he was going to die within two hours:

The morning came, and I remember the first sensations that came to me: relief at not being dead, and then — joy. Overwhelming, total, heart-bursting joy. Joy for breathing, joy for being alive. Joy for seeing the sun shine through the window. Joy for feeling the texture of the sheets around me. Joy for seeing the face of my father. Joy for feeling the breath enter my heart. Joy for feeling joy.

Mr. Safi asks, “So, friends, what would you do if you had two hours to live? And just as importantly, what are you going to do in these next two hours?”

There will come a time in our lives when we will truly have only two hours to live. How lovely will it be to have lived a life in which we have told everyone how loved they are, asked for forgiveness for all that we have to atone, and forgiven all those around us who yearn for forgiveness. How lovely to greet that moment with no regrets, but with a sense of purpose, meaning, love, tenderness, and forgiveness.

What would you do if you had two hours to live? Benedictine monastics and many poets throughout the ages tell us what happens to our lives when we “keep death daily before our eyes.” We try to live the majority of our days as if they were our last, enabling us, when we come to the moment of our deaths, to know that we have lived a good life–a life surrendered to love.

And now, here is wisdom from Thomas Keating (1923-2018), to help us all learn to live lives surrendered to love. I think you will be very glad you took the time to watch this transformational tribute.

Thomas Keating — A Life Surrendered to Love

Comment

September 27, 2020

23 Spiritual Practices Taught by The Rule of Benedict

Practice is how people develop the skills to become adept at anything. Music students practice their instruments. Gymnasts practice routines, yoga students practice poses, swimmers practice strokes, and tennis players practice their serves. Successful organizational leaders practice self-mastery and teamwork. Just as all these people practice to become more proficient, spiritual seekers practice in order to become better at living a spiritual life.

What is the Rule of Benedict?

Do you yearn for a good life, and do you desire to see good days? Near the end of his life in 547 AD, Benedict of Nursia wrote a a guide to living, in the company of other humans, the kind of good days that add up to a good life. The Rule of Benedict has resonated through more than 1400 years and today is followed around the world by thousands of monastics and oblates (people associated with monasteries who live and work outside the monastery). This “little rule for beginners” serves to develop a spirituality made up of practices, which Benedictines incorporate into their relationship with God and their interactions with the people with whom they live and work.

What is Benedictine Spirituality? What are Benedictine Practices?

Because I couldn’t find relevant, simple answers online to the questions, “What is Benedictine Spirituality?” and “What are Benedictine practices?” I decided to publish this summary of 23 habits Benedictines seek, through lifelong practice, to cultivate into a lifestyle.

23 Benedictine Practices

I’ve drawn this list of 22 (+ 1 = 23) Benedictine practices (arranged alphabetically) from Stepping into the Oblate way of life, published by St. Benedict’s Monastery in 2017, when Laureen Virnig OSB served as Director of Oblates.

1. Awareness of God

In Benedictine practice we acknowledge the primacy of God and look for God in the ordinary events of each day. This practice is not particular to Benedictines, however. Cultivating awareness of God is important for all who seek a meaningful spirituality. In this article, Benjamin Schäfer, who calls himself an intercessory musicianary, blog theologian, and pilgrim on the narrow road of learning to love, writes in depth about ways to foster awareness of God.

2. Being in Right Relationship

“Being in right relationship” is wholly other than “being in the right relationship.” It isn’t about finding the right person for me; it’s about being the right person to others in the way I show respect to them, in the way I accept their humanity—even their weaknesses and irritating personality traits. For Benedictines, being in right relationship means that we treat everyone we encounter with loving kindness and patience. This Benedictine practice is exceedingly difficult for most of us, for most of our lives. We stumble through being in right relationship. We practice clumsily like beginners running through piano scales. But, we keep practicing, because we hope that eventually, with faithful practice, that our way of being present to others will be as rich and meaningful as Chopin’s Nocturns are mysteriously rich with meaning when played by the virtuoso Arthur Rubinstein near the end of his life. Listen here:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LoTQF...

3. Commitment to Growth (Conversatio)

On the blog “Catholic Beer Club,” Br. Ignacio Gonzalez, OSB writes that the Benedictine practice of Conversatio requires that we never stop asking hard questions about our personal growth. “Am I growing in my true identity as a son or daughter of God? Or, am I living a lie, allowing myself to be conformed to every whim and temptation of my fallen nature?” To complete our personal transformation, we never stop changing. We always can go deeper in prayer, grow more open to the truth, enrich our understanding of the will of God, and learn what, in this moment at this time, is good, acceptable, and right.

4. Community

The Sisters of St. Benedict in Ferdinand, Indiana explain the importance of community life in Benedictine practice on their website. Before writing his Rule, Benedict lived for years as a hermit. Through this experience, he came to believe that authentic spiritual growth happens only when we life with and among “flawed human beings whose faults and failings are only too obvious.” In community we struggle through the practice of being in right relationship with people who are “stubborn…dull…undisciplined…restless…careless… scatterbrained…irritating…and tiresome.” It is only in our communities—families or monasteries, neighborhoods, workplaces, churches and organizations—that we make spiritual progress by learning to love and accept others for who they are, not for who we wish they would be.

Photo credit: Kamaljith on VisualHunt.com/ CC BY

Photo credit: Kamaljith on VisualHunt.com/ CC BY5. Gratitude

Brother David Steindl-Rast of the Gut Aich Priory monastery in St. Gilgen, Austria, is the founder and senior advisor for A Network for Grateful Living. His books include Gratefulness, A Listening Heart, and most recently, a new autobiography, i am through you so. Interviewed by Krista Tippett for her podcast On Being, Brother David talks about gratitude as the true wellspring of joy. Reading the transcript or listening to the podcast is worthwhile. This discussion shows that it’s impossible to isolate any Benedictine practice as independent of the others. They are all intertwined.

6. Hospitality

The Benedictine practice of hospitality is radical. Kyle T. Kramer explains in his 2011 article for America Magazine that hospitality, for a Benedictine, means to welcome all others as Christ, “to recognize that despite vast differences, the diverse human family is part of the same God-given belonging, and we need one another to survive and thrive.” This means facing our fears, letting prejudice and certitude die in us, and rooting ourselves in the love of God, “the alpha and omega of the entire creation, the force that pulls everyone and everything toward a center that can hold.” Benedictines hold strong convictions, but experience shows “strident, uncompromising voices” tend to foster arguments, tensions, and hostilities—not peace and love. Benedictine hospitality requires us to moderate our own views and voices, and in this day and age, as in all ages, moderation is supremely radical.

7. Humility

St. Benedict’s chapter on humility is one of the longest in the Rule. An essay by the Sisters of St. Mary’s Monastery in Rock Island, IL explains that the Benedictine practice of humility is the opposite of humiliation. Humility fosters stronger, healthier connections within communities by breaking down the artificial barriers between individuals. Humility helps us accept our gifts and talents joyfully while letting go of our false selves. Humility helps be more authentically, beautifully, and lovingly human. Read the full essay to learn more about how humility helps us grow in the love of God and deepens our bonds with each other.

8. Lectio divina / Listening to God’s Word in Scripture

Directly translated, Lectio Divina means “divine reading. It includes reading, reflecting, responding to and resting in the Word of God — not in a scholarly way, not to make a sermon to preach to others, but simply to nourish and deepen our own relationship with the Divine. This article on the Contemplative outreach website explains the history of lectio divina, and offers instruction in how to do it.

Photo on VisualHunt.com

Photo on VisualHunt.com9. Listening

The first word of the Rule of Benedict is “Listen.” The Benedictine practice of listening is the heart of Benedictine spirituality, for not only are we instructed to listen constantly to one another in community, to leaders, to guests, to the sick, to our inner selves, and most of all, to God, we must also “attend to [what we hear] with the ear of the heart.“ As Good Samaritan Sister Clare Condon writes, “Listening with the ear of the heart can be a scary experience because it can call me to radical change, to a transformation of my limited human perspective. This is not simply a change in my opinion or even in my ideological stance, but a much deeper change in my attitude, a real change in my way of being and doing.” Listening is integral to the practice of conversatio, indeed to all the practices, which, as Laureen Virnig OSB teaches to Oblates in formation, are inseparable woven together to make of our spirituality a living tapestry.

10. Liturgical prayer / Liturgy of the Hours

The Benedictine practice of Liturgical prayer is one of Benedictine spirituality’s most visible, unmistakable hallmarks. As Sister Julie explains on the blog A Nun’s Life, “The Liturgy of the Hours is made up of specific prayers said at various time (“hours”) during the day and night. You can read more about the Liturgy of the Hours by clicking here, but the best way to learn about Liturgical prayer is to find a monastery and experience it.

11. Mindfulness

Mindfulness is a trending word these days — yogis, psychologists, educators, physicians, and practically everyone else is talking about the importance of quieting our busy minds in order to become more aware of the present moment. Benedictines say mindfulness is as much as a Christian and biblical concept as it is a Buddhist one. The Benedictine practice of mindfulness, like all the Benedictine practices, is lifelong. Digital nun, writing for ibenedictines.org tells us, “The practice of mindfulness, which for a Christian must always be the practice of mindfulness of the presence of God, is not something we learn in a few hours or even a few years. It is a lifetime’s work, and it is not to be rushed or short-circuited in any way.” Click here to read hints on how to enjoy this lifelong practice.

12. Moderation in All Things

The Benedictine practice of Moderation in All Things is another that is trending today, under the word “balance.” In the blog Echoes from the Bell Tower, Fr. Adrian Burke, OSB writes, “Benedict insists in his Rule that we must balance our lives with prayer and work, with reading and recreation, with rest and activity.” Benedictines attempt to incorporate all of these important aspects into every day. Fr. Adrian also writes, “This kind of wisdom is why St. Benedict’s Rule continues, after more than 1,500 years now, to stir the hearts of men and women who want to live their lives entirely for Christ.” In other words, Benedict’s Rule stirs the hearts of those who want to live each day fully. Paradoxically, the key to a full life, is to understand that “all things are to be done with moderation.” (Rule of St. Benedict 48:9)

13. Obedient Listening to God, Self, Others

Obedience is a concept 21st-century souls don’t generally like to consider. We prefer concepts like freedom and independence. In a podcast at DiscerningHearts.com from the Missionary Benedictines of Christ the King Priory, Fr. Mauritius Wilde O.S.B explains that obedience means to listen. Obedience is an act of letting go of the egoistic will. While submission is an act of youth, true obedience can only come as a response of maturity. We become obedient only after we know our own will. Only after we have come to understand our desires are we capable of relinquishing them in service of others. Therefore in Benedictine spirituality, “mutual obedience” is a habit to be shown by all to one another. As a Benedictine practice, obedience is intimately linked to being in right relationship, conversatio, humility, and listening. Benedictine obedience is ultimately directed not to other humans or to ourselves, but through the agency of others and the deepest yearnings of our own hearts, in love, to God.

14. Patience

In his blog Benedictine Monks, Fr. Brendan Rolling, OSB of St Benedict’s Abbey of Atchison, Kansas quotes Abbot Martin Veth: “To will what God wills and because He wills it, this is the essence of patience. Patience does not relieve us of our natural feelings of aversion, irritation, and indignation, but it controls and rises above these feelings… Our Lord felt the natural impulse to avoid suffering, but He set aside and refused to listen to this feeling: ‘Father not my will but Thine be done’.…Where does this patience show itself? It shows itself in the way (emphasis mine) you put up with the many things of your daily life, sickness, death, war, persecution, mishaps and misfortunes of every kind.” In other words, without awareness of God and without gratitude, indeed, without the interweaving of all these practices into our lives, patience cannot exist.

15. Peace

Sister Joan Chittister is an extraordinarily prolific writer and among the most famous living Benedictines. In an article for HuffPost Sister Joan tells us that a Benedictine lifestyle is an “an oasis of human peace in a striving, searing, simmering world.” This lifestyle disallows war and violence on any level, including the root causes of violence—ambition, greed, waste of resources, class distinctions, and the “hubris that leads to the oppression of others, that justifies force as the sign of our superiority.” This lifestyle makes ample room for what it values—“community, prayer, stewardship, equality, stability, conversion, peace — all [which] make for communities of love.” Without humility, Sr. Joan explains, there can be no peace. “It is humility that makes us happy with what we have, willing to have less, kind to all, simple in our bearing, and serene within ourselves.” It only takes 2-3 minutes to read her article. If there is anything that everyone of us in the whole world needs more of right now, it’s peace.

16. Prayer

Prayer is essential to a Benedictine lifestyle. Many Oblates rely on Give Us This Day, a monthly prayer book with simplified daily prayer for morning and evening, to help us participate in the Divine Office when we are away from the monastery. For most Oblates. that’s most of the time. You can order a free copy of Give Us This Day, published by Liturgical Press, by clicking here.

17. Reverence for All Creation

In his book Humility Rules: Saint Benedict’s Twelve-Step Guide to Genuine Self-Esteem, Augustine Wetta, a Benedictine monk, teaches, “The sum of all virtues is reverence.” In this 2-minute video, Father Mark Goring (Companions of the Cross) says “This profound and humble …[Benedictine practice of] reverence for all things is one of the great foundations of Benedictine spirituality.” He explains that this reverence flows from prayer. “Their prayer discipline is based on the rhythms of the universe.” Benedictine reverence for all creation applies to nature and all creatures, to the objects we use and make, and to all people—pilgrims, the broken and downtrodden, to every single human, including ourselves.

18. Service to Others

The Benedictine practice of service to others is intimately entwined with the reverence for all creation, and another of the great foundations of Benedictine spirituality. In a blog hosted by Holy Wisdom Monastery of Madison, Wisconsin, Lynne Smith, OSB writes that in America, middle and upper class people tend to imagine they are living self-sufficiently, believing they are able to “pretty much take care of [their] needs.” This self-deception is possible only when “[w]e take for granted all the people who work behind the scenes to provide the food for the store, to staff and maintain the filling station and all those people involved in the health care system. We are no more self-sufficient than the poor whose dependence on the service of others can’t be hidden.” The Rule of Benedict teaches that “Monastics should serve one another” (35:1). Lynne Smith elaborates, “All this service is sacred and to be done with reverence… service is seen as a form of prayer, a way of seeking God.” This practice is also linked inextricably to gratitude, as we give thanks for the ways we can serve and for those who serve us.

19. Silence

Silence in Benedictine practice is knit together with listening and with prayer. The website of Subiaco Abbey in Arkansas tells us, “Modern monks like to point out that first word in the Rule is to ‘Listen,’ which can’t be done while talking! God gave us two ears and one mouth, so we should use them in that order. This emphasis on silence is so that we can learn to listen to God more acutely…This kind of sensitivity and awareness makes it easier to pray at all times.” This article explains that silence is healthy for community life and fosters the learning of reverence for all creation. Benedictines are called to strive for silence and have a love for silence.

20. Stability of Heart

Monsignor Charles Pope seems to be saying in the blog post, “A Reflection On the Benedictine Vow of Stability” for Community in Mission of the Archdiocese of Washington (DC), that stability of heart is the Benedictine practice our chronically unstable contemporary society most desperately needs. In her blog, Presbyterian minister Lynne Baab offers ways for those of us who do not live in a monastery to embrace stability.

Commit to daily, weekly or monthly prayer disciplines.

Be faithful in demonstration of family and community commitments, for example, by calling parents every week at the same time, checking in regularly on neighbors, affirming and listening to coworkers.

Listen to the Holy Spirit speaking through scripture and through the insights of others.

Listen to your body, to “the negative and irritating things” like “our fatigues and headaches and muscle aches, revealing to us the lack of balance and health in our lives.”

Be willing to wait. This grows our ability to rest in stability.

Benedictine monastics make a three-fold commitment to stability, conversion (conversatio), and obedience. The Friends of St. Benedict website says “The Rule offers people a plan for living a balanced, simple, and prayerful life.” Simple, yes. Quick and easy, no. As Joan Chittister puts it, Benedictine practices build a spirituality that will enable us to go on “beyond disappointment, beyond boredom, beyond criticism, beyond loss.” Benediction spirituality is “for the long haul.”

21. Stewardship of Resources

Stewardship of resources, as a Benedictine practice, flows out of the commitment to stability, explain the monks and oblates of Saint Meinrad Archabbley, in this post on “Environmental Stewardship” on the blog Echoes from the Bell Tower. “We are all accountable as steward of creation,” they tell us. The concept that we are not above nature but are part of it, stems from the practice of humility, of knowing who we are, how we are, and to whom we belong.

22. Work

Yes, work, too, is a basic tenet of Benedictine Spirituality, Chris Sullivan nexplains in her blog post “Work and Prayer in the Style of St. Benedict” for Loyala Press. She reminds that in the Rule of Benedict, “in the economy of monastic life,” prayer “is work and work is prayer.” While [t]ime set aside for prayer can be a great blessing, …we can turn all of our daily tasks into prayer when we bring to them the awareness of ourselves in relationship with our ever-present God.”

Which brings us back to awareness of God, to the beginning again.

22+1 = 23 / Begin again

Benedictines read a portion of the Rule of Benedict every day. Every four months, we begin again at the beginning–so we read the Rule three times every year. Having the mind of a beginner, being receptive to starting anew, starting fresh, starting over–this, too, is a Benedictine practice.

Although well into the middle years of an average life span, I am a rank beginner, a mere toddler in Benedictine practice. Only a year ago, after a year of formation, I became an Oblate of Saint Benedict’s Monastery in St. Joseph, MInnesota. In no way am I qualified to be a teacher of the Benedictine way of life. In this article, I have merely collected and summarized what other, more experienced Benedictines have taught and published. I hope this list (compiled in September, 2018) is helpful, perhaps even inspiring.

Are you a thoughtful reader (and maybe even a writer) who seeks a peaceful, just, spiritual approach to life?

I’m interested in connecting person-to-person with others who share my values, who want to participate with me in building a meaningful network of relationships that will serve to support us on our spiritual journey. If you fill out this form, I’ll respond from my personal email. This will not subscribe you to a contact management software program, and you won’t get an onslaught of computer-generated emails begging you to buy my books and services. Let’s make ours a truly human–a listening and reverent–connection.

[contact-form][contact-field label=”Name” type=”name” required=”1″ /][contact-field label=”Email” type=”email” required=”1″ /][contact-field label=”Website” type=”url” /][contact-field label=”Comment” type=”textarea” required=”1″ /][/contact-form]

Featured Image:

Downloaded from the web site of the Bodleian library: [1]

MS. Hatton 48 fol. 6v-7r of the Bodleian library in Oxford. This manuscript is a copy of St. Benedicts rule.

Public Domain

File:MS. Hatton 48 fol. 6v-7r.jpg

Created: 8th century date QS:P,+750-00-00T00:00:00Z/7

April 23, 2020

Judith Valente–poet, journalist, and Benedictine oblate–on "How To Live"

At the intersection of reading and writing, in the spaces where listening, silence, prayer, and wonder happen–there is poetry. There, too, is where I find support for living as a Benedictine.

Some months ago I decided that my blog will focus on “Reading, Writing, and the Benedictine way of life.” Since then, I’ve been pondering what I want to write about the way I live now.

Judith Valente has made it easy for me. Her recently published How to Live: What the Rule of St. Benedict Teaches Us About Happiness, Meaning, and Community is a book I would like to give to everyone who cares to know more about why I choose to live as a Benedictine, and what that means.

This book defines and discusses the things that matter. It gives practical suggestions for making our busy, daily lives meaningful and joyful. “Community. Simplicity. Humility. Hospitality. Gratitude. Praise. These are the pillars of Benedictine spirituality,” Valente writes.

Last autumn at Saint Benedict’s Monastery, more than twenty nuns and oblates were working to beautify the woods. Judith Valente was on campus and joined our picnic lunch. I was in charge of preparing and cleaning up the meal, which meant I didn’t have the opportunity for the leisurely visit I wanted to have with this fellow poet/writer and Benedictine Oblate. In the five minutes I spent chatting with her, I recognized a kindred spirit. She had this book coming out in April, so I grabbed a card to remind myself to get a copy. It hoped it would substitute for the conversation I missed.

It isn’t enough to merely read How to Live. In this way it’s like the book it’s about, The Rule of Benedict. To gain wisdom, to apply “how” to actual living, it is necessary to turn ideas into practices. Then, over time, your understanding of what it’s really all about grows–but understanding is never complete.

I didn’t expect to give this book 5 stars on Goodreads, but I did! I’ve read a lot of books by Benedictines, and there came a point at which I started thinking, “How much more could there possibly be to say about a Rule that’s been around for more than 1500 years?” I’ve read the “major” contemporary Benedictine writers, those on the radar of many kinds of readers–Kathleen Norris, Esther de Waal, Joan Chittister, and Macrina Wiederkehr. There are also many “minor” writers. Mostly other Benedictines read them.

I tend to read books by “minor” Benedictine nuns, monks, and oblates out of a kind of commitment to the community. I expect to gain wisdom; but I don’t expect to encounter a book I will recommend to people who don’t call themselves Benedictine. These books tend to be too counter-cultural or other-worldly to suit the majority of my friends and relatives.

I read them because as Benedictines, we love and support one another even when we’re not amazingly accomplished or clever, and to read someone’s book is to make a statement that you care about what they think. We believe that everyone is important and should be patiently heard. In listening to one another, we always learn something. Spending time with a Benedictine nun, monk, or oblate is always good for me. And I’ve found the worldly distinctions of “major” and “minor” (as well as everything having to do with popularity) become irrelevant in the monastery.

A Benedictine doesn’t try to become “major.” It goes against the Benedictine practice of humility. But, for the sake of all the people whose lives could benefit from the application of the principles in Judith Valente’s How to Live, I hope this will become a major book by a major Benedictine writer.

Whether or not that happens, it’s a book I will return to, as I return to The Rule of Benedict and important commentaries on it, again and again, always as a beginner, listening to hear newfound wisdom for this day.

Here are five reasons I highly recommend How to Live by Judith Valente:

How to Live by Judith Valente addresses the way average Americans live today, in the workaholic, perfectionistic world outside of monasteries;

The writing is excellent. Judith Valente is a poet and award-winning journalist;

It’s simple, uncomplicated, and understandable (which is not to say that it’s easy. The book challenges us to grow spiritually and morally, and that kind of growth requires purposefully diligence);

It’s practical — each chapter ends with ideas for enriching true happiness, meaning, and community in our lives;

It’s relevant for all people seeking a more meaningful life, not only for those who practice a Benedictine lifestyle.

Which books do you turn to again and again for wisdom? Do you know anything about the Benedictine way of life? Are you interested in learning more?