Andrew Cartmel's Blog, page 9

July 28, 2019

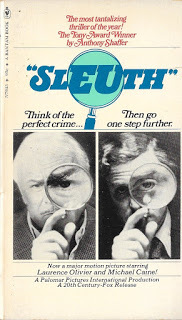

Sleuth by Anthony Shaffer

Reading the plays of Agatha Christie, (such as Go Back for Murder) has got me digging into other classic stage mysteries and thrillers, like Ira Levin's Deathtrap...

Reading the plays of Agatha Christie, (such as Go Back for Murder) has got me digging into other classic stage mysteries and thrillers, like Ira Levin's Deathtrap...And, like Ira Levin, Anthony Shaffer is a great admirer of Christie. In fact he calls her "the most revolutionary storyteller of our time."

Anthony Shaffer is the man who wrote Sleuth, a classic in this genre if ever there was one.

First staged in 1970, Sleuth ran for eight and a half years in London's West End, and for four and a half on Broadway.

According to Shaffer it only ended on Broadway because of the release of the movie. (As he observes, the film version didn't seem to deter British audiences.)

Sleuth is also one of only two non-musical stage shows to run over 2,000 performances in both New York and London. Interestingly, the other is Arsenic and Old Lace, also a dark comedy with murder in its heart.

Sleuth is also one of only two non-musical stage shows to run over 2,000 performances in both New York and London. Interestingly, the other is Arsenic and Old Lace, also a dark comedy with murder in its heart.Before Sleuth, Anthony Shaffer had written one stage play and co-written some crime novels with his identical twin brother, Peter, who by 1970 was already a world famous playwright, having written The Royal Hunt of the Sun, among others. Peter would go on to write Equus and Amadeus, two of my all time favourites.

Although Anthony didn't quite achieve a track record like his twin, Sleuth remains one of the great stage successes of the 20th Century. And another all time favourite of yours truly.

Although Anthony didn't quite achieve a track record like his twin, Sleuth remains one of the great stage successes of the 20th Century. And another all time favourite of yours truly.It's also a great title, so I was intrigued to learn that it didn't come easily — the play started life as Anyone for Tennis? which I think is somewhat weak and commonplace, and was briefly Deaths Put on by Cunning, a quote from Hamlet, which is evocative but unwieldy.

The script itself also underwent radical transformations. In its first draft Shaffer had included Andrew Wyke's wife and mistress as characters. The play just wasn't working, until he had the inspired notion of removing both the wife and mistress and making them merely offstage presences.

The script itself also underwent radical transformations. In its first draft Shaffer had included Andrew Wyke's wife and mistress as characters. The play just wasn't working, until he had the inspired notion of removing both the wife and mistress and making them merely offstage presences.This is particularly interesting in view of Agatha Christie's own principle that a good stage mystery or thriller generally requires simplification — which often means removal of characters. In the case of adapting her own Hercule Poirot novels for the theatre, she invariably removed Poirot altogether!

Sleuth concerns the aforementioned Andrew Wyke, a successful mystery novelist, and Milo Tindall, who is having an affair with Wyke's wife. Wyke doesn't seem at all bothered by this — but is that really the way he feels?

Sleuth concerns the aforementioned Andrew Wyke, a successful mystery novelist, and Milo Tindall, who is having an affair with Wyke's wife. Wyke doesn't seem at all bothered by this — but is that really the way he feels? Some combative, and dangerous games-playing ensues — don't forget, Wyke specialises in fashioning murderous puzzles in his books...

I'm deliberately avoiding saying too much about the plot of Sleuth because I don't want to give away any of the dazzling surprises. But I should at least quote some of the shockingly funny dialogue.

When Wyke convinces Milo to stage a fake break-in at his house, he insists on him doing so in disguise in case anyone sees him. Milo demands to know who's likely to be outside such an isolated country house. "A passing sheep rapist," suggests Wyke.

When Wyke convinces Milo to stage a fake break-in at his house, he insists on him doing so in disguise in case anyone sees him. Milo demands to know who's likely to be outside such an isolated country house. "A passing sheep rapist," suggests Wyke.There's also a choice bit where Wyke badmouths his wife, who is of course Milo's lover, saying that she, "converses like a child of six, cooks like a Brightlingsea landlady, and makes love like a coelacanth."

(Brightlingsea is, or was, a dingy coastal town in Essex; a coelacanth is a prehistoric fish.)

Sleuth is imbued with a knowledge, and a love, of classic detective stories, populated as they were by brilliant, eccentric amateurs.

Sleuth is imbued with a knowledge, and a love, of classic detective stories, populated as they were by brilliant, eccentric amateurs.And it joyfully creates a clashing dissonance by slamming these tropes against the real world.

As a police inspector remarks in the second act, "We may not have our pipes, or orchid houses, our shovel hats or deer-stalkers, but we tend to be reasonably effective."

The pipe and deer-stalker are Sherlock Holmes references. The orchid house belonged to Nero Wolfe. The shovel hat to Dr Gideon Fell.

Sleuth is a work to stand beside these greats in the genre.

In 2001 Anthony Shaffer could gleefully assert that there was a production of Sleuth being performed somewhere in the world every day since it first appeared.

In 2001 Anthony Shaffer could gleefully assert that there was a production of Sleuth being performed somewhere in the world every day since it first appeared.If there is one near you, I'd urge you to go and see it.

Failing that, get hold of the play script and read it.

Failing that, you might want to see the 1972 film. But avoid the 2007 film like the plague. It's adapted for the screen by Harold Pinter but is a dreadful aberration.

But that's another story, for another post.

(Image credits: The Bantam movie tie in and the Marion Boyars edition with the black and orange cover are scanned from my own library. The other covers, including one apparently in Farsi, are from Good Reads.)

Published on July 28, 2019 02:00

July 21, 2019

Appointment with Death by Agatha Christie

Appointment With Death is the 19th Hercule Poirot novel, published in 1938.

Appointment With Death is the 19th Hercule Poirot novel, published in 1938.It is one of Christie's greatest stories — one of her most original and ingenious set-ups, a truly powerful situation with fascinating, indelible characterisation.

It is not, however, one of her greatest novels, for a very surprising reason — which, like Poirot, I will save for a revelation at the very end of this piece.

Certainly the novel has a superb, arresting opening with Hercule Poirot in his hotel in Jerusalem, overhearing a fragment of conversation drifting in through his window:

Certainly the novel has a superb, arresting opening with Hercule Poirot in his hotel in Jerusalem, overhearing a fragment of conversation drifting in through his window:"You do see, don't you, that she's got to be killed?"

"The question floated out into the still night air, seemed to hang there a moment and then drift away down into the darkness towards the Dead Sea."

"The question floated out into the still night air, seemed to hang there a moment and then drift away down into the darkness towards the Dead Sea."Fantastic stuff, and beautifully written. Certainly one of Christie's best ever beginnings.

And the story just gets better as we're introduced to the Boynton family, a group of young American tourists who are ruled with an iron hand by their elderly "hippopotamus" of a mother.

And the story just gets better as we're introduced to the Boynton family, a group of young American tourists who are ruled with an iron hand by their elderly "hippopotamus" of a mother.Old Mrs Boynton turns out to be a "mental sadist" — she loves inflicting mental torment on her children who, despite being adults, are all still under her thumb.

They all "depend on her financially" (like the family of Gordon Cloade in Taken at the Flood), but it's more than that.

They all "depend on her financially" (like the family of Gordon Cloade in Taken at the Flood), but it's more than that.Mrs Boynton is like something out of Stephen King, a "hulk of shapeless flesh, with her evil, gloating eyes."

Christie reveals her to have once been a wardress (i.e. female warden) of a prison. It makes perfect sense. Indeed, it was the ideal job for her — she "became a wardress because she loved tyranny."

Christie reveals her to have once been a wardress (i.e. female warden) of a prison. It makes perfect sense. Indeed, it was the ideal job for her — she "became a wardress because she loved tyranny."Retired now, Mrs Boynton dominates and intimidates her family the way she once did her prisoners. (In fact, effectively they are her prisoners.)

And she bullies them not physically but psychologically (psychology is a major feature of the novel).

And she bullies them not physically but psychologically (psychology is a major feature of the novel).So it will come as no surprise to you to learn that the old hippopotamus is soon bumped off (by lethal injection — hence the syringes which feature on the various covers here) and Poirot is duly enlisted to bring his "highly specialised services" to bear.

In his classic manner, he gathers the various interested parties together at the end of the book, and there is considerable excitement and pleasure as he enumerates the features of the case and ponders who might be guilty.

In his classic manner, he gathers the various interested parties together at the end of the book, and there is considerable excitement and pleasure as he enumerates the features of the case and ponders who might be guilty.The slow, inexorable discussion of the possibilities, and the sifting of the suspects, creates almost unbearable suspense.

And I never could have guessed the final revelation...

And I never could have guessed the final revelation... But I was, for the first time reading a Christie, disappointed by it.

And that was because I'd previously read the stage play which Christie had adapted from the book — which features a different culprit.

And the solution in the play is truly stunning, reinforcing the central situation and themes of the story in the way that the ending of the novel doesn't.

I believe Christie herself sensed this weakness and that's why she came up with a better ending for the play — and how.

I believe Christie herself sensed this weakness and that's why she came up with a better ending for the play — and how.Don't hesitate to read the novel of Appointment with Death. It's fine. But once you've done so — or even before you do so — get hold of the play and read that.

The denouement is a knockout. One of her best ever.

(Image credits: The covers of the various editions are from the admirable GoodReads except for the fab front and back cover of the Dell Map Back edition which are from Flickr. and the poster for the play is from Foothill Theatre.)

Published on July 21, 2019 02:00

July 14, 2019

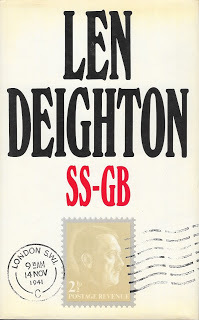

SS GB by Len Deighton

Somehow I'd got hold of the idea that Len Deighton was past his prime when he wrote SS GB. Nothing could be further from the truth. He is at the height of his powers here.

Somehow I'd got hold of the idea that Len Deighton was past his prime when he wrote SS GB. Nothing could be further from the truth. He is at the height of his powers here.I'm so glad that the excellent TV adaptation spurred me into finally reading this book. I'd say that SS GB is one of Deighton's finest... I only hesitate because it's such a bleak and harrowing narrative...

The novel depicts a Britain which was defeated and subjugated by the Nazis and is set not long after the invasion. It follows the exploits of Douglas Archer, a Scotland Yard detective who is increasingly out of his depth in a murder investigation which leads him into some very dark waters indeed.

The novel depicts a Britain which was defeated and subjugated by the Nazis and is set not long after the invasion. It follows the exploits of Douglas Archer, a Scotland Yard detective who is increasingly out of his depth in a murder investigation which leads him into some very dark waters indeed.

This is of course an alternate history novel — and, effectively science fiction, though Deighton's publishers would never use that term, since it would be commercial suicide for a bestselling thriller writer to be categorised in that genre ghetto.

There's a thriving subgenre of alternate history stories, detailing for instance what would happen if the South had won the Civil War (Bring the Jubilee by Ward Moore) or if the Spanish Armada had successfully invaded (Pavane by Keith Roberts).

Indeed, SS GB isn't the first work of fiction to depict a Nazi victory (The Sound of His Horn by Sarban). Nor would it be the last (Fatherland by Robert Harris). But it's probably the best.

Deighton's tale is intriguingly reminiscent of The War of the Worlds in its portrait of devastation in recognisable London locations such as Putney Hill and Wimbledon. "Halfway up Wimbledon High Street — at the corner that makes such a perfect spot for an ambush — there was the blackened shell of a Panzer IV."

Deighton's tale is intriguingly reminiscent of The War of the Worlds in its portrait of devastation in recognisable London locations such as Putney Hill and Wimbledon. "Halfway up Wimbledon High Street — at the corner that makes such a perfect spot for an ambush — there was the blackened shell of a Panzer IV." And Deighton uses the brilliant, offhand device of describing the headlines on a newspaper used to wrap fish and chips (what could be more cheerfully English?): Canterbury declared open city as German tanks enter.

And Deighton uses the brilliant, offhand device of describing the headlines on a newspaper used to wrap fish and chips (what could be more cheerfully English?): Canterbury declared open city as German tanks enter.There are also chilling throwaway lines such as the mention of "the notorious concentration camp at Wenlock Edge."

Deighton describes this parallel reality so distinctly and with such telling detail it's as if he's actually seeing it.

Deighton describes this parallel reality so distinctly and with such telling detail it's as if he's actually seeing it. The book is immaculately researched, as you'd expect from the author of the brilliant novel Bomber and a series of masterly nonfiction works about World War 2.

But more than that, it's beautifully written: "the colourless sun only just visible through grey clouds, like an empty plate on a dirty table cloth."

But more than that, it's beautifully written: "the colourless sun only just visible through grey clouds, like an empty plate on a dirty table cloth." The story is intensely imagined visually: "the wind was plucking at their coats, and lashing the trees into a demented dance... dark clouds were racing."

A German officer on a motorcycle "craned forward over the handlebars like a witch riding a broomstick" racing through "the evil-smelling London fog that swayed in front of the headlight... sometimes moving aside to reveal long ghostly corridors that ended in miserable grey streets."

A German officer on a motorcycle "craned forward over the handlebars like a witch riding a broomstick" racing through "the evil-smelling London fog that swayed in front of the headlight... sometimes moving aside to reveal long ghostly corridors that ended in miserable grey streets."And there are superb descriptions which make the reader physically present in the moment: "the shockwave of the explosion punched him in the face like a padded glove."

And splendid observations, like the parachutist who split his footwear on landing and now "massaged his broken shoe as if it were a small animal that needed comforting."

And splendid observations, like the parachutist who split his footwear on landing and now "massaged his broken shoe as if it were a small animal that needed comforting."This is wonderful writing with a real edge of poetry, as with this observation of interned prisoners waiting for interrogation: "But mostly they did no more than stare into space, eyes unfocused as they tried to see tomorrow."

Like I said, Deighton is at the peak of his powers here.

This outstanding novel has only, I think, two flaws. For one chapter in the entire book (Chapter 37) he abandons his hero, Douglas Archer, and moves to the viewpoint of someone entirely different.

I can see why he did it, but this is an artistic flaw and I'm surprised it didn't offend his sense of craftsmanship; it's certainly jarring to the reader.

And I winced at the cruel, ruthless and casual way he killed off some of his characters. But that was a valid artistic decision — just one I wouldn't have shared. And it's certainly true to the facts of wartime. And it's nothing new in Deighton's work. He did the same in Bomber.

And I winced at the cruel, ruthless and casual way he killed off some of his characters. But that was a valid artistic decision — just one I wouldn't have shared. And it's certainly true to the facts of wartime. And it's nothing new in Deighton's work. He did the same in Bomber.(Image credits: The main illustration is my scan of my own copy of the original Jonathan Cape hardcover, which I greatly enjoyed reading; the Panther paperback with the skull badge is also my own scan of my own copy. All the various other covers are from the excellent Good Reads.)

Published on July 14, 2019 02:59

July 7, 2019

The Old Devils by Kingsley Amis

This novel is considered by Martin Amis to be his father's greatest achievement, so we can rest assured it is anything but. (Kingsley's greatest achievement was his superb ghost story The Green Man.)

This novel is considered by Martin Amis to be his father's greatest achievement, so we can rest assured it is anything but. (Kingsley's greatest achievement was his superb ghost story The Green Man.) But The Old Devils is good. As with Ending Up, it deals with elderly people nearing the end of their lives — although it doesn't have the intense clarity of Ending Up, thanks to the large cast of characters and their complex web of relationships.

Some of these characters are vivid enough to begin to emerge from the haze around the time philandering poet Alun Weaver enters the story upon his return to Wales. But although a few of them are sufficiently distinctive to intermittently fix themselves in the reader's mind — Peter (fat), Charlie (alcoholic) — others stubbornly remain a mystery.

Some of these characters are vivid enough to begin to emerge from the haze around the time philandering poet Alun Weaver enters the story upon his return to Wales. But although a few of them are sufficiently distinctive to intermittently fix themselves in the reader's mind — Peter (fat), Charlie (alcoholic) — others stubbornly remain a mystery.  Usefully, though, all three of those characters appear in this nimble trio of sentences:

Usefully, though, all three of those characters appear in this nimble trio of sentences: "Charlie appeared. He was followed by someone who at first looked to Alun like an incredibly offensive but all too believable caricature of Peter Thomas aged about eighty-five and weighing half a ton. At second glance he saw that it was Peter Thomas."

Which gives some idea of how Amis is operating in his classic comic mode in this novel.

Which gives some idea of how Amis is operating in his classic comic mode in this novel.Here he is giving an account of a hangover: "He felt as if about two-thirds of his head had recently been sliced off and his heart seemed to be beating somewhere inside his stomach, but otherwise he was fine."

Even more acute is his depiction of the psychological consequences of heavy boozing (of which there is a great deal in this book) — "he felt that everything he had was lost and everyone he knew was gone."

There's also a fond moment when Charlie thinks the drink has caused him to lose his mind and that the sounds emanating from a man have no meaning...

There's also a fond moment when Charlie thinks the drink has caused him to lose his mind and that the sounds emanating from a man have no meaning...Then he realises it's just an American tourist trying to speak Welsh to him.

You'll find some other classic Amis gags here — such as the insulting reference to a Welsh person as a "violator of siblings"; and great use of language as in the description of "uncommonly horrible china dogs."

Or his evocation of a modern high tech shower with "a massive control-dial calibrated and colour-coded like something on the bridge of a nuclear warship."

Or his evocation of a modern high tech shower with "a massive control-dial calibrated and colour-coded like something on the bridge of a nuclear warship." The Old Devils is often a very dark novel but Amis includes some impressively contrasting moments of affirmation. The wedding at the end of the book is often cited...

But I personally preferred, indeed rather adored, the scene of the male old devils listening to trad jazz records: "through a roaring fuzz of needle-damage the sounds of 'Cakewalkin' Babies' emerged."

Amis goes on to describe "an oldster capering about on his own like a mad thing." And the effect of the music on Malcolm — who previously seemed a bit of a twat — is really quite moving, especially when he has to wipe his eyes.

If you haven't read anything by Kingsley Amis, don't start with this novel. Instead grab the aforementioned The Green Man.

But once you've read that, you may want to take a crack at this highly regarded late offering.

But once you've read that, you may want to take a crack at this highly regarded late offering.And if you do, you might find this (by no means complete) list helpful:

Malcom (infatuated with Rhiannon) married to Gwen (who is shagging Alun, and horrible to Rhiannon); Peter (fat, sympathetic) married to Muriel (incredibly nasty);

Alun (poet) married to Rhiannon (toothless, indulging Malcolm, mother of Rosemary); Charlie (alcoholic) married to Sophie (shagging Alun); Dorothy (toxic bore).

Alun (poet) married to Rhiannon (toothless, indulging Malcolm, mother of Rosemary); Charlie (alcoholic) married to Sophie (shagging Alun); Dorothy (toxic bore).Happy reading!

(Image credits: The main image is my scan of my own copy of the New York Review Books edition which, despite some annoying typos, is the one I'd recommend. The other covers are from Good Reads. You may notice that receptacles for booze are a popular theme.)

Published on July 07, 2019 02:00

June 30, 2019

Taken at the Flood by Agatha Christie

"I really didn't see that coming," could well be my motto when reading Agatha Christie.

"I really didn't see that coming," could well be my motto when reading Agatha Christie.And, boy, does it ever apply to this novel, which throws some tremendous surprises at the reader in its final pages.

This is a superior Hercule Poirot mystery with a genuinely terrific set up. It is the 28th Poirot novel, first published in 1948 ,and the shadow of World War 2 falls emphatically across the story.

The book begins with an air raid and bombs falling on the house of a millionaire, Gordon Cloade. Cloade is killed, as are all the servants. Cloade's beautiful young bride and her brother survive.

The book begins with an air raid and bombs falling on the house of a millionaire, Gordon Cloade. Cloade is killed, as are all the servants. Cloade's beautiful young bride and her brother survive.In the first few pages Hercule Poirot, taking shelter at a gentleman's club from another air raid, hears this tale.

And what's more, he hears how the beautiful young bride has deprived Gordon Cloade's family of all the money they thought was guaranteed to them — through Gordon's characteristic generosity.

And what's more, he hears how the beautiful young bride has deprived Gordon Cloade's family of all the money they thought was guaranteed to them — through Gordon's characteristic generosity. And what's even more, he hears the rumour that the bride's first husband, reportedly dead of a fever in the African bush, may actually be alive.

And what's even more, he hears the rumour that the bride's first husband, reportedly dead of a fever in the African bush, may actually be alive.In which case Cloade's fortune will go to his family after all...

Two years later the pot really begins to boil and Poirot re-enters the story at the behest of the Cloade family.

Two years later the pot really begins to boil and Poirot re-enters the story at the behest of the Cloade family.This fascinating story is studded with equally fascinating characters. I particularly liked Frances, the wife of lawyer Jeremy Cloade. She's utterly unscrupulous, and completely unashamed about it.

When Frances and Jeremy are discussing what would happen if Rosaleen, that inconvenient young bride, was to suddenly die, "something seemed to pass through the room — a cold air — the shadow of a thought..."

When Frances and Jeremy are discussing what would happen if Rosaleen, that inconvenient young bride, was to suddenly die, "something seemed to pass through the room — a cold air — the shadow of a thought..." But the whole Cloade clan has a motive for murder and Rosaleen is so obviously a target that considerable suspense soon starts to ratchet up.

But the whole Cloade clan has a motive for murder and Rosaleen is so obviously a target that considerable suspense soon starts to ratchet up. Luckily she's under the protection of her brother, a former commando, as unscrupulous as Frances and another great character.

Generally Christie doesn't do much in the way of reflecting the period her books are set in, but this one conveys a vivid picture of England just after the war, with its rationing, bureaucracy and high taxes.

Generally Christie doesn't do much in the way of reflecting the period her books are set in, but this one conveys a vivid picture of England just after the war, with its rationing, bureaucracy and high taxes. Indeed it is the most period-conscious of the Poirot's I've read so far except for Hallowe'en Party, where everybody was complaining about allowing dangerous lunatics to run around loose instead of locking them up in asylums.

She also has some rather more profound things to say about what "war did to you. It was not the physical danger... the crisp ping of a rifle bullet as you drove over a desert track. No, it was the spiritual danger of learning how much easier life was if you ceased to think..."

She also has some rather more profound things to say about what "war did to you. It was not the physical danger... the crisp ping of a rifle bullet as you drove over a desert track. No, it was the spiritual danger of learning how much easier life was if you ceased to think..."Once this intricate and explosive situation has been fully delineated, along with the characters — and once the killing begins — Poirot decisively enters the story.

He's particularly good value this time around, quoting Sherlock Holmes ("I have my methods"), making an "unsuccessful attempt to look modest" and outlining his approach to investigation.

He's particularly good value this time around, quoting Sherlock Holmes ("I have my methods"), making an "unsuccessful attempt to look modest" and outlining his approach to investigation.

"Talking to people. That is what I do. Just talk to people."

Finally, having employed his technique, Poirot is ready to reveal all. He goes to the denouement. "Into an atmosphere quivering with danger... Once more, Poirot dominated the situation."

And what a superb revelation it is. I never saw it coming.

(Image credits: The Tom Adams cover for the main image is from Pinterest. The other covers (isn't the Italian Mondadori version fab?) are from Good Reads, including the Swedish version which has taken "taken at the flood" rather too literally. Except for the Brazilian Colecção Vampiro edition — I'm very fond of this series — which is from Sebo do Messias.)

Published on June 30, 2019 03:16

June 23, 2019

Yellowstone (Series 1) by Taylor Sheridan and John Linson

Regular readers of this blog may be aware of my high regard for Taylor Sheridan. In my opinion he is the finest screenwriter working in America today.

Regular readers of this blog may be aware of my high regard for Taylor Sheridan. In my opinion he is the finest screenwriter working in America today. Here's a list of the films he's written: Sicario, Hell or High Water, Wind River and Sicario 2. Every one of them gets my highest recommendation, as you'll see if you check out the links.

Recently Taylor Sheridan has branched out into directing — doing an outstanding job on his own script for Wind River.

And now he is masterminding a television series, carrying out the mammoth task of both writing and directing all the episodes of Series 1 of Yellowstone.

And now he is masterminding a television series, carrying out the mammoth task of both writing and directing all the episodes of Series 1 of Yellowstone.The show is co-created by John Linson, and Linson wrote the first drafts of the first two episodes, which were then rewritten by Sheridan.

John is the son of Art Linson, a distinguished movie producer who has written two excellent and bitingly funny books about working in Hollywood.

I mention the Linsons because Taylor Sheridan used to work for them as an actor on their series Sons of Anarchy. And they fired him when he asked for a raise — which goes to show that, admirably, no grudges were held, or Yellowstone couldn't have happened.

Yellowstone is the name of the vast ranch in Montana owned by John Dutton, played by Kevin Costner. (The show is actually shot in magnificent locations in Utah.)

At first Dutton seems to be a noble, upright man. A multi-millionaire modern cowboy who is standing staunchly against the corrupt forces of the 21st Century...

Which are personified by Danny Huston as Dan Jenkins, a weaselly property developer.

Which are personified by Danny Huston as Dan Jenkins, a weaselly property developer. We applaud Dutton when he outwits Jenkins and prevents him building a vast housing development on the virgin land adjoining Dutton's ranch.

But it becomes evident that John Dutton is far from untarnished. This is emphatically brought home when he sends his enforcer, Rip (Cole Hauser) to murder someone who is making life difficult for him.

Indeed, it turns out John Dutton is pretty much Don Corleone on horseback, and Yellowstone is The Godfather on the Range.

Indeed, it turns out John Dutton is pretty much Don Corleone on horseback, and Yellowstone is The Godfather on the Range.At the heart of this engrossing, cut-throat saga is Dutton's tangled, indeed tormented, relationship with his children:

His son Jamie (Wes Bentley) who has been groomed as a legal and political fixer to protect his father's empire, but who is set to fall out with him in a spectacular fashion...

His son Jamie (Wes Bentley) who has been groomed as a legal and political fixer to protect his father's empire, but who is set to fall out with him in a spectacular fashion...His hard drinking, hard nosed daughter Beth (Kelly Reilly), who has a lot of hilarious dialogue, and a truly tragic backstory.

And, most of all, his youngest son Kayce (Luke Grimes) who is a violent ex Navy SEAL who has forsaken his father and all his wealth to marry a Native American woman, Monica (Kelsey Asbille, who was also excellent in Wind River) and live on the reservation with her.

The reservation and the Native American population is an important presence in the show, spearheaded by Thomas Rainwater (played by Gil Birmingham, a regular collaborator of Sheridan's, who was terrific in both Hell or High Water and Wind River).

Rainwater embodies the watchful bitterness of the original Americans, who were slaughtered and had their land stolen out from under them by the likes of John Dutton.

And he is carefully plotting his revenge against Dutton. And with his political connections, and the wealth of a casino behind him, Rainwater may well prevail in this fascinating reworking of the classic Hollywood tale of cowboys versus Indians.

And he is carefully plotting his revenge against Dutton. And with his political connections, and the wealth of a casino behind him, Rainwater may well prevail in this fascinating reworking of the classic Hollywood tale of cowboys versus Indians.These description just scratch the surface of Yellowstone, which is dense with fascinating characters and situations and which crackles with intense drama, sudden violence, and dark humour.

It's currently my favourite TV series. Do check it out if you get the chance.

(Image credits: The main poster — chaps and Winchester, "original scripted series" — is from Pinterest. The bulk of the posters are from The Movie DB. The photo of Costner, Hauser and Taylor Sheirdan is from the BTS Look at Yellowstone on Youtube. The superb black and white photo of Nicole Sheridan and Taylor Sheridan is by Christian Anwander and is from a first rate feature on Sheridan at Esquire. The image of Costner looking from the right of the frame in profile is from The Daily Caller where they provide the welcome news that the second series is confirmed.)

Published on June 23, 2019 02:28

June 16, 2019

Cari Mora by Thomas Harris

Thomas Harris is my favourite living crime novelist... maybe my favourite living novelist. He writes slowly, sometimes a paragraph a day, sometimes nothing.

Thomas Harris is my favourite living crime novelist... maybe my favourite living novelist. He writes slowly, sometimes a paragraph a day, sometimes nothing. So perhaps it isn't surprising, though it is frustrating, that it's taken 13 years for his new novel to arrive.

It was however, worth the wait. I've read some snotty reviews of Cari Mora, motivated by the fact there is nothing of Hannibal Lecter in this book. But I actually think it's all the better for that.

In fact I think this might be Harris's masterpiece. It's a short book — probably more like a novella in length. But it is beautifully, perfectly wrought.

In fact I think this might be Harris's masterpiece. It's a short book — probably more like a novella in length. But it is beautifully, perfectly wrought.The novel focuses on the woman named in the title. And Cari Mora is a magnificent character. Clearly Thomas Harris wants to write about people we can care about — love, even.

Towards the end of his spate of Hannibal Lecter novels, Harris started trying to humanise Lecter and justify him. Culminating in Hannibal Rising and some questionable results.

But here he is starting with a clean slate, and a wonderful new character and we can care about Cari without restraint. As a result, this book is — despite the terrible things it depicts — more positive and life affirming than his previous ones.

Once more we have the monster and maiden dichotomy, with a gruesome psychopathic killer pitted against a strong, compassionate heroine. The heroine in this case of course is Cari, a refugee with considerable experience of violence.

And the monster is Hans-Peter Schneider. Hans-Peter is a human trafficker — unlike Hannibal, a commercially motivated monster. And Cari is in his sights because she might expedite access to a fortune in gold.

For all its horrors, this is a sunnier tale than any of the Hannibal Lecter stories, both figuratively and literally — we're back in the Florida Harrison has so lovingly evoked before in portions of Red Dragon — but here it's the location for the entire book.

And it's such a beautifully written book. Consider this description of the aftermath of an attack on a village by Marxist guerrillas:

"They had blown some walls off the schoolhouse and the wind was blowing through the strings of a burning piano, sighing, sighing and whining through the strings in the gusts that blew sheet music across the road."

"They had blown some walls off the schoolhouse and the wind was blowing through the strings of a burning piano, sighing, sighing and whining through the strings in the gusts that blew sheet music across the road."I also adored the fact that Cari is an animal lover (as is Harris; see him here at a bird sanctuary and above, hugging a possum called Bruce) and animal life is a constant, splendidly evoked presence in the book.

Like the cockatoo standing on Cari's wrist "eyeing her earrings" and who has a repertoire of salty phrases garnered from its "checkered life."

Like the cockatoo standing on Cari's wrist "eyeing her earrings" and who has a repertoire of salty phrases garnered from its "checkered life."And did I mention that Harris is funny? But his humour sits in constant proximity to menace and potential mayhem: "The bedrooms were a piggish mess... The one made-up bed had some lewd comic books and the five parts of a field-stripped AK-47 scattered on it."

Of course Harris knows how many parts there are to an AK-47, and exactly how to assemble one, as he will show us on the next page. His research is exemplary.

Thomas Harris is the master of the super-charged

policier

. His sardonic tone, the brilliance of his prose, his supreme command of suspense and his gift for violent action were all, I believe, honed by his reading the works of John D. MacDonald.

Thomas Harris is the master of the super-charged

policier

. His sardonic tone, the brilliance of his prose, his supreme command of suspense and his gift for violent action were all, I believe, honed by his reading the works of John D. MacDonald.(There is an echo of MacDonald's The Drowner in a terrifying moment in Cari Mora.)

Thomas Harris is John D. MacDonald's true successor in these regards and also in his concerns for animals and the environment, and his loving depiction of Florida.

Thank heavens Harris is still with us, and still writing. May he write many more novels. And perhaps even speed up a little...

Thank heavens Harris is still with us, and still writing. May he write many more novels. And perhaps even speed up a little...(Image credits: The book covers — there are only two so far — are from Good Reads. The cover of The Drowner by John D. MacDonald is also from Good Reads. The photo of Thomas Harris in a blue blazer is by Robin Hill and is from Penguin. The other photos of Thomas Harris are by Rose Marie Cromwell and come from an excellent interview with Harris by Alexandra Alter in the New York Times. The AK-47 diagram is from Mouse Guns. The much more lovely white cockatoo is from Pinterest.)

Published on June 16, 2019 02:00

June 9, 2019

Murder on the Orient Express by Agatha Christie

Murder on the Orient Express is the tenth Hercules Poirot novel, published in 1934.

Murder on the Orient Express is the tenth Hercules Poirot novel, published in 1934. I was familiar with it long before I read it, through the two movie adaptations.

In many ways it's the archetypical Agatha Christie novel, with its challenging mystery and brilliant resolution.

Finally reading it was satisfyingly like arriving at a long-awaited rendezvous.

The story begins beautifully and concisely and evocatively: "It was five o'clock on a winter's morning in Syria."

The story begins beautifully and concisely and evocatively: "It was five o'clock on a winter's morning in Syria." And it makes for rather odd reading now, with exotic place names such as Mosul so horribly familiar to us because of the current conflict in Syria.

But we are in the 1930s here and the romance of travel is very much to the fore. "A whistle blew, there was a long, melancholy cry from the engine... The Orient Express had started its three-days' journey across Europe."

It seems obvious now, but a train — what's more, a stranded train stuck in a snow drift — is a truly inspired location for a murder investigation...

Because, of course, that's what happens. As with Death in the Clouds, a diverse and intriguing collection of characters have been brought together by their travel plans.

There is an aristocratic old Russian lady, the aptly named Princess Dragomiroff, with a "yellow, toad-like face."

And Mary Debenham, a pretty young English woman who displays an "almost feverish anxiety" when it looks like she might miss the train.

And Mary Debenham, a pretty young English woman who displays an "almost feverish anxiety" when it looks like she might miss the train. Plus a chap called Foscarelli who moves with a "swift, cat-like tread" and who might be one of those "nasty murdering Italians..."

And of course, there is Hercules Poirot.

Whereas in Death in the Clouds a poison dart dispatched a passenger in broad daylight, this time there is a murder in the middle of the night. A stabbing.

Whereas in Death in the Clouds a poison dart dispatched a passenger in broad daylight, this time there is a murder in the middle of the night. A stabbing.And Poirot is enlisted to find the culprit.

This novel is the polar opposite of Sad Cypress — a Poirot tale where the victim was almost unbearably undeserving of her fate.

Here the guy was a gangster who really got what was coming to him.

I won't say too much about the plot, except that the train getting stuck in the snow interferes crucially with the killer's plans.

As usual, there is considerable fun at our hero's expense — he is thought to look like "a women's dress maker" — as the other characters initially underestimate him.

But soon Poirot is cracking the puzzle in his own unique way: "to solve a case a man has only to lie back in his chair and think."

And his formidable intellect begins to make itself evident. "Poirot's eyes... were bright and sharp like a bird's."

And his formidable intellect begins to make itself evident. "Poirot's eyes... were bright and sharp like a bird's." Following his own advice, "Hercules Poirot sat very still. One might have thought he was asleep."

And then the solution comes to him. "His eyes opened. They were green, like a cat's."

And then the solution comes to him. "His eyes opened. They were green, like a cat's." And what a solution it is.

A true classic.

(Image credits: As usual, the main image with its gorgeous Tom Adams cover painting is a scan of my own copy. All the other covers save one are from the ever-useful Good Reads, including the beautiful art nouveau Richard Amsel painting for the American movie edition, with its train/dagger. The exception is the Norwegian edition with the cool, retro cut-away diagram illustration, which is from Bergen Bibliotek.)

Published on June 09, 2019 03:31

June 2, 2019

"Is That Cat Still Up That Tree?" — The Norman Conquests by Alan Ayckbourn

When I first set about learning my craft as a writer, the playwrights I most admired were Harold Pinter and Tom Stoppard. I was aware of Neil Simon and Alan Ayckbourn (who occupied similar positions on either side of the Atlantic) — funny, accessible and hugely popular.

When I first set about learning my craft as a writer, the playwrights I most admired were Harold Pinter and Tom Stoppard. I was aware of Neil Simon and Alan Ayckbourn (who occupied similar positions on either side of the Atlantic) — funny, accessible and hugely popular. But compared to the austere brilliance of Pinter or the pyrotechnic dazzle of Stoppard I consider Simon and Ayckbourn too broad, clownish, lowbrow. I didn't think there was much going on in their work... Their stuff was just too damned simple

I didn't realise how much craft was involved in achieving that appearance of simplicity. As with the smoothly swimming swan, there is a hell of a lot of activity going on unseen beneath the surface.

These days I tend to prefer Simon and Ayckbourn to Pinter and Stoppard. And The Norman Conquests may well be Alan Ayckbourn's masterpiece.

It is a series of three linked plays which can be (and have been) performed in any order. They deal with one weekend in the life of the philandering librarian Norman (His conquests are the women who succumb to his dubious charms.)

He has planned to take his wife's sister Annie away for a dirty weekend, but fate has other ideas...

I've never seen these plays performed. Just read them and heard an excellent radio version. And it really doesn't matter which one of the three you start with, or which one follows it, although each sequence has its own particular pleasure and shift of emphasis.

Ayckbourne is a truly great writer with unforgettably brilliant observations of character. When discussing the dull and lugubrious local GP, Annie says "I'm really very fond of Tom but he really is terribly heavy going. Like running up hill in roller skates."

(Image credits. For such an important sequence of plays, it's almost impossible to find good images online. The Penguin edition, with the John Ireland cartoon cover, is my own scan of my own copy and it is, in all modesty, the only decently sharp version to be found anywhere on the internet. The others are from Good Reads.)

Published on June 02, 2019 06:30

May 26, 2019

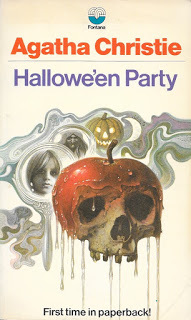

Hallowe'en Party by Agatha Christie

This is the 39th Hercule Poirot, published in 1969, and sees Agatha Christie cautiously dipping her toe into the turbulent waters of the Swinging Sixties.

This is the 39th Hercule Poirot, published in 1969, and sees Agatha Christie cautiously dipping her toe into the turbulent waters of the Swinging Sixties. I've been particularly looking forward to reading this novel as part of my Poirot project, because of the gorgeous Tom Adams cover art — which I've always admired, even back in the days when I snobbishly declined to read Agatha Christie...

(Incidentally, that fantastic image of the apple transforming into a skull, and the water dripping from it, will make sense very rapidly when you read the book, although I don't intend to give any spoilers here.)

(Incidentally, that fantastic image of the apple transforming into a skull, and the water dripping from it, will make sense very rapidly when you read the book, although I don't intend to give any spoilers here.)The book begins with some adroit, busy scene-setting as preparations are made for the titular Halloween party, with character largely established through dialogue.

Among those present is Ariadne Oliver, whom I was pleased to find. Ariadne is a recurring minor character in Christie's work, and I first encountered her in Cards On the Table. She's a spinster crime novelist — sort of Agatha Christie's alter ego.

Among those present is Ariadne Oliver, whom I was pleased to find. Ariadne is a recurring minor character in Christie's work, and I first encountered her in Cards On the Table. She's a spinster crime novelist — sort of Agatha Christie's alter ego. Unlike Christie, Ariadne's detective is a Finn. (When asked, "Why a Finn?" Ariadne responds, "I've often wondered.")

Like Christie, Ariadne Oliver is a bestseller and a big success, and there's an amusing throwaway bit here when she's asked if her books make a lot of money, which sends "her thoughts flying to the Inland Revenue." Christie must have known a thing or two about high income tax...

Anyhow, Ariadne's presence at the party is actually the trigger for a murder to take place there. The police, of course, are baffled, and Ariadne summons her old friend Hercule Poirot and the carefully engineered Christie plot is underway.

Hallow'een Party is the newest in the Poirot series that I've read, and indeed the most recent of Christie's novels — which caused me some concern... A friend who's a Christie buff had told me that it dated "from Christie’s declining years when her faculties are not what they once were."

Hallow'een Party is the newest in the Poirot series that I've read, and indeed the most recent of Christie's novels — which caused me some concern... A friend who's a Christie buff had told me that it dated "from Christie’s declining years when her faculties are not what they once were."At first this prescription seemed glumly accurate. After the drama of the initial murder, the book seemed a trifle dull — somewhat colourless and repetitive.

Was Christie having difficulty with writing in the milieu of a changing world? Had the sexual permissiveness, and casual drug use of the Sixties baffled her?

Well, Agatha Christie had always written about drugs, including cocaine and heroin... Although now things are somewhat different. Ariadne's friend Judith Butler says, "Peculiar drugs and — what do they call it? — Flower Pot or Purple Hemp or L.S.D."

Well, Agatha Christie had always written about drugs, including cocaine and heroin... Although now things are somewhat different. Ariadne's friend Judith Butler says, "Peculiar drugs and — what do they call it? — Flower Pot or Purple Hemp or L.S.D." On the other hand, Christie had never written very directly about sex. However, all that changes in this novel, and a rather lifeless book surprisingly comes to life — and Christie herself snaps awake — with the introduction of two children of the era.

Desmond and Nicholas are a pair of teenage boys who were witnesses to (and also suspects in) the murder at the Halloween party. The scene where Poirot interviews them is utterly priceless, and these kids are great characters, desperately striving as they do for sophistication.

Desmond and Nicholas are a pair of teenage boys who were witnesses to (and also suspects in) the murder at the Halloween party. The scene where Poirot interviews them is utterly priceless, and these kids are great characters, desperately striving as they do for sophistication.They offer Poirot their own theories on the possible identity of the murderer. Starting with the "Sex starved" school mistress. "Lesbian?" suggests Nicholas "in a man of the world voice."

And then there's the curate (assistant vicar) who "might be a bit off his nut" and have committed the murder. "'Perhaps he exposed himself to her first,' said Nicholas hopefully."

This scene, with the two boys enthusiastically theorising about possible culprits and motives, is fabulous. And also a rather hilarious parody of mystery fiction tropes.

As the boys roll out these preposterous suggestions, offering our hero the benefit of their wisdom, "They both looked at Poirot with the air of contented dogs who have retrieved something useful which their master has asked for."

As the boys roll out these preposterous suggestions, offering our hero the benefit of their wisdom, "They both looked at Poirot with the air of contented dogs who have retrieved something useful which their master has asked for."This must be one of Dame Agatha's best similes ever, and had me laughing out loud. Indeed this sequence was pretty much the high point of the book for me and, I suspect, for Christie herself.

Which is not to say that she short changes us on an unpredictable plot, or a grippingly suspenseful climax.

Which is not to say that she short changes us on an unpredictable plot, or a grippingly suspenseful climax. There is a brilliant piece of classic Christie misdirection here, concerning the murder victim having witnessed an earlier murder.

Plus the usual rush of excitement for the reader as we race towards a very Christie conclusion.

Ultimately, I felt that Hallowe'en Party more than delivered the goods, which is great news since I have a lot of late period Christie novels to read.

Ultimately, I felt that Hallowe'en Party more than delivered the goods, which is great news since I have a lot of late period Christie novels to read. And Nicholas and Desmond are quite wonderful characters. I like to think that if Christie had lived long enough she would have spun them off into a series of adventures of their own.

In any case, here she was clever enough to enlist them in the climax of the story.

In any case, here she was clever enough to enlist them in the climax of the story.(Image credits: The main image, of the beautiful Tom Adams cover painting, is once again scanned by me from my own copy. The other covers are from good old Good Reads, including the nice Bulgarian one which reuses the Adams art. I also particularly like both the Portuguese versions — with different titles. It's nice to see the Colecao Vampiro series still going strong in 1970 with Poirot eo Encontro Juvenil (Poirot and the Youth Gathering), and A Festa das Bruxas (literally, A Witches Party) has a charming cover painting, don't you think? Including a cat...)

Published on May 26, 2019 09:44