Paul Preuss's Blog, page 2

January 31, 2014

Book Reviews: A New Century, a New Light

The Brick Tower Press logo features a brick water tower built in 1898 on the Long Island estate of the railroad executive and yachtsman J. Rogers Maxwell. iBooks was founded by the late Byron Preiss, an innovator in book packaging and publishing for the digital era.

After Byron Preiss died in a traffic accident in 2005, hundreds of works he’d packaged for others or published under his own imprints, including iBooks, went on auction. John T. Colby, Jr., the founder and publisher of Brick Tower Press, acquired the assets in 2006, including several stories and novels I’d written for Byron, a longtime friend.

One of them was the novel Core, which John has recently reissued in a revised ebook version, giving me the chance to fix one of those asleep-at-the-keyboard goofs in the original Morrow hardcover (repeated in the AvoNova mass market paperpack). No, there are no hummingbirds in the Middle East. Not in this edition, anyway.

The original reviews were mixed. The New York Times’s Gerald Jonas found “a savvy, hard-science techno-thriller about the hardest science of all,” which Kirkus seconded with “a fascinating scientific-technical spectacle,” but Publisher’s Weekly felt the narrative fell flat, “defeated by tediously detailed scientific and technical explanations” – although it conceded “the tantalizing premise and some brisk, exciting passages.”

The human element took a beating, though: “cliché-ridden family history, digressive character development” (PW), and “tepid romancing, humdrum father-son clashes” (Kirkus). With those potshots in mind, when I reread the novel to put it in shape for the digital version, I braced for the worst.

Writers are used to letting their finished manuscripts cool for a couple of weeks, then checking them again before sending them off to agents or publishers, for good reason: they read differently. On this late rereading, Core had cooled enough for the whole world to change.

The same novels are different in the 21st century because their readers are different. These days I doubt even hard-core science fiction critics would worry, as Tom Easton did in his positive Analog review, whether Core is “a bit too contemporary to qualify (in some minds) as SF.” The contemporary world we live in is the sf world of the late 20th century.

We can see the people we’re talking to on the phone. We carry powerful computers around in our hands. The computers themselves talk back to us. And in this century, the firewall between literary fiction and science fiction has all but crumbled (though Margaret Atwood hasn’t gotten the word yet).

Among the many works by literary writers who aren’t shy about science fiction, a couple that come to mind are David Mitchell’s Cloud Atlas, short-listed for the Booker Prize, which moves from the past to the far future and back again with near-Shakespearian mastery, and Jennifer Egan’s A Visit from the Goon Squad, winner of the Pulitzer among other prizes, a deft and (eventually) moving tale which, incidentally, shows uncanny foresight into the near future of social media. As does Dave Eggers’s eerie The Circle, his latest.

Core doesn’t compare with these – it’s an adventure, although one meant to engage the mind, and it moves around a lot, from the High Atlas to the Tonga Trench to the deserts of Nevada, West Texas, and the Middle East. But fathers and sons and some of the ways things can go seriously awry between them, and between lovers, are a substantial part of the story.

These are common human problems. Does that make them clichés? If treated mechanically, yes, but that’s not what I found when I reread Core. Instead I found complicated characters written with truth and feeling and humor. Many of those passages are among the strongest and most personal I’ve put into words.

Core has its quirks, and of all the reviews, Gary K. Wolfe’s in Locus best expressed what I may not have admitted then, but do now:

… we’re back in the early 1940s at the University of Nevada, where Cyrus Hudder – Leidy’s father – suffers a series of misfortunes…. The narrative begins jumping among several time frames, paralleling Cyrus’ career with Leidy’s and exploring with unusual insight the ways the lives of scientists determine their attitudes toward science and its institutions. The novel is at its strongest as it brings a whole half-century of scientific history to bear on its immediate crisis.

But then it gets weird. What promised to be an exceptional novel of character and science begins to turn into a James Bond thriller…. On a scene-by-scene basis, everything in Core works vividly and convincingly, but it’s hard to avoid the suspicion that, in the end, a truly excellent novel of science got ambushed [by a suspense thriller].

I hope readers who are interested in these questions of both content and style will take the opportunity to judge for themselves. When written fiction works better than movies it’s because the words on the page are what create the images and dialogue and special effects and, yes, the music in the reader’s head: everybody’s movie is different. In this new century, Core is a new book even for its author. (For one thing, it’s now an alternate-world historical!)

On the Brick Tower Press website John Colby has also made available the complete six-volume set of trade paperback editions of Arthur C. Clarke’s Venus Prime. More on that next time.

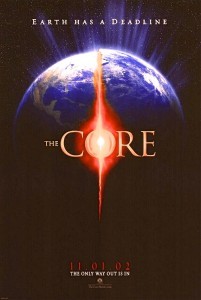

PS – Because a number of people have asked about the similarities between aspects of Core and the dismal 2003 movie The Core, my first two posts on this blog discuss some of the more glaring of those, uh, coincidences.

December 9, 2013

Patrick Leigh Fermor: A Home in Greece

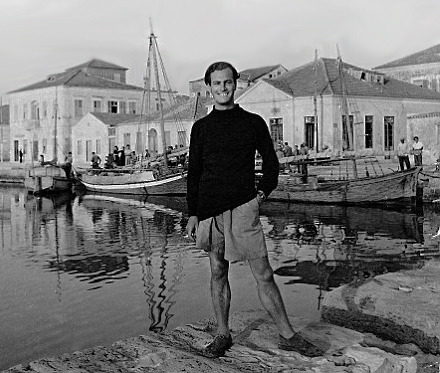

Paddy in Ithaca, 1946, photographed by Joan Rayner (Joan Leigh Fermor)

Over Thanksgiving Debra and I spent some time with Sid Mintz, whom I began to know while taking his first-year anthropology class at Yale, and his wife, Jackie. Both later moved to Baltimore when he co-founded the anthropology department at Johns Hopkins University.

Catching up, I asked Sid if he was familiar with Patrick Leigh Fermor, whom I’d been writing about lately. The answer was a surprised yes: while he knew little else about him, Sid said Leigh Fermor was the author of one of the best books on the postwar Caribbean. This is high praise from “the doyen of Caribbean anthropology,” as Wikipedia calls Sid.

The Traveler’s Tree was Paddy’s first book, written almost by accident. In her biography Patrick Leigh Fermor: An Adventure, Artemis Cooper relates that he’d been struggling to write about Greece and was out of money. A Greek friend, Costa Achillopoulos, offered Paddy his entire advance on a book of photographs he’d been commissioned to do of the Caribbean, if he’d come along and write photo captions and magazine pieces to help finance the trip.

Paddy and his lifelong companion, Joan Rayner, herself a photographer, set off with Achillopoulos in the fall of 1947 for a strenuous six-month journey through the region. Back in Europe, Paddy burrowed into a way of writing that would be with him all his life – deeply layered, wildly associative, often interrupted for other projects, requiring frequent moves, fueled (cheerfully, for the most part) by alcohol, and alternating between exhilaration, drudgery, and despair. The Traveler’s Tree took two years and was published to acclaim in 1950.

Paddy and Joan were already back in Greece, gathering material for the two most astonishing travel books ever written about that much-traveled country. Mani is mostly about the southern Peloponnese, where he and Joan later built their home, and Roumeli is concerned mostly with northern Greece, but the ostensible subject never confined him.

Early in Mani, for example, under the guise of commenting on the “absorptions and dispersals” of the Greek world, Paddy begins lightly: “I thought of the abundance of strange communities: the scattered Bektashi and the Rufayan, the Mevlevi dervishes of the Tower of the Winds, the Liaps of Souli….” The single sentence continues for two full pages without so much as a semicolon.

In a crime novel of mine set in Athens (now in progress), two characters have memorized Paddy’s riff, and mine it for code words:

“An empty shoulder holster!” Charleton turned to Scott, amazed. “Mr. Jordan! Would you by any chance be one of those English remittance men of Kyrenia?”

“No sir, I am one of the Basilian Monks.” Scott’s face was an expressionless mask.

“Idiorrythmic or Cenobitic?”

“Idiorrythmic, of course.”

“And of what use would an empty holster be to an Idiorrythmic Basilian monk, Mr. Jordan?”

English remittance men and Basilian Monks occur about midway through the list, nestled between the Sahibs and Boxwallahs of Nicosia and the anchorites of Mt. Athos. (The research to find out just who these people are is part of the fun of reading Mani, so I won’t deprive the reader.)

While scribbling these encyclopedic ruminations, Paddy was caught up in events that brought him both fame and distress. Ill Met by Moonlight, by W. Stanley (Billy) Moss, Paddy’s second in command during the abduction of General Kreipe, was finally published and shortly became one of Michael Powell’s lesser films, starring Dirk Bogarde as Major Patrick Leigh Fermor.

Paddy had read the first draft in 1945, when Moss first requested clearance from the Special Operations Executive. “It is not a very good book,” he wrote in his forwarding note to Colonel Talbot-Rice, preserved in Paddy’s SOE file made public after his death. He was particularly irritated at Moss’s “attitude of patronage to the Cretans that hints that they are only fairly gentle savages,” but recognized that after “pretty drastic editorial revisions … It will sell like blazes.”

He never stood in the way of Moss’s work; his own account of the kidnapping was published here and there in scattered passages. He never effectively challenged the idea that Kreipe’s kidnapping was directly responsible for the deaths of many civilians and the annihilation of numerous Cretan villages.

For me, Artemis Cooper’s discussion of these events was revelatory. Specifically, the destruction of Anogeia was retribution not for Kreipe but for a later operation directed by Moss, who blew up a nearby bridge and slaughtered a German patrol with no attempt to divert blame from the villagers.

Paddy returned to the subject in a 1991 private letter quoted by Cooper: a school teacher from one of the destroyed villages, although opposed to Kreipe’s kidnapping, had written him that “not a single inhabitant of the Amari would have been spared if the abduction had never happened.”

The underlying cause of the savagery was best summed up by Tom Dunbabin, a longtime SOE operative on Crete: “This was the last act of German barbarity,” he wrote, its object to cover the German retreat and “commit the German soldiers to terrorist acts so that they should know that there would be no mercy for them if they surrendered or deserted.”

“If all time is eternally present/ All time is unredeemable,” T.S. Eliot wrote in Burnt Norton. Often in a long life Paddy visited and revisited the scene of his youthful bravado. His daunting memory could be as much a burden as a gift.

###

Here at last, the concluding volume of Patrick Leigh Fermor’s walk across Europe in the 1930s: The Broken Road: From the Iron Gates to Mount Athos.

November 21, 2013

Patrick Leigh Fermor: His Charm Conquered (Almost) All

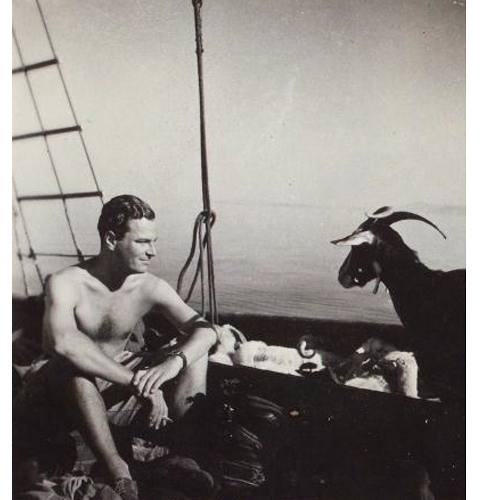

Handsome Paddy on a caique…

Patrick Leigh Fermor was raised virtually an orphan, his parents divorced, his father away in India, his mother often neglectful. He managed to get himself expelled from every English boarding school that took him in. Eighteen years old and at loose ends, instead of joining the army he decided to walk to Constantinople (he would never call it Istanbul). The year was 1933.

A Time of Gifts: On Foot to Constantinople, From the Hook of Holland to the Middle Danube was written mostly in the 1960s and first published in 1977, but I didn’t stumble on it until the late 1990s. Reading the book was an unsettling but ultimately liberating surprise. Its author was not just an extraordinary stylist but a wholly different person than the one I thought I knew from reading about his wartime adventures in German-occupied Crete.

…with friend. (Photo Joan Leigh Fermor, Nat’l Library of Scotland)

In Patrick Leigh Fermor: An Adventure, Leigh Fermor’s biographer, Artemis Cooper, aptly describes his writing as “built up, layer upon layer, over the years…,” strata “so folded over one another… that the book reads like a journey across a continent that exists somewhere between memory and imagination.”

Paddy actually did walk many a mile (Cooper and everyone who knew him calls him Paddy, and so will I), and he often slept on the ground or in shepherds’ huts or other rough accommodations, but rather more of his journey was spent traveling by train, automobile, boat, or horseback in the company of aristocratic hosts to whom he’d been introduced by letters, some from his numerous bohemian but upper-class friends.

He had no money and no titled ancestors. What kept him going was charm, and the basis of all genuine charm, a fascination with the people he met. He had an insatiable curiosity, a gift for languages, unbounded daring and brass, and an astonishing, if not completely faultless, memory. He applied it to memorizing poems in a volume of Horace his mother had given him for the trip, including one in particular, To Thaliarchus, that he’d translated before being kicked out of King’s School, Canterbury – for holding hands with a greengrocer’s daughter.

The charm lasted all his life. In May 2006, not long after Paddy’s ninety-first birthday, Anthony Lane published a deft profile in The New Yorker, from which I learned that I was one among a great many of Paddy’s fans and a latecomer at that. Lane, more familiar as the magazine’s stern film critic, gushed over his subject, who has “so much living to his credit that the lives conducted by the rest of us seem barely sentient – pinched and paltry things, laughably provincial in their scope.”

Lane’s piece begins with the kidnapping of General Kreipe (see my former post) and later quotes its most famous incident, which comes straight from a digression in A Time of Gifts, but which Paddy often repeated elsewhere:

During a lull in the pursuit, we woke up among the rocks just as a brilliant dawn was breaking over the crest of Mount Ida…. the general murmured to himself:

Vides ut alte stet nive candidum

Soracte…

It was one of the ones I knew! I continued from where he had broken off:

nec jam sustineant onus

Silvae laborantes…

The general’s blue eyes swiveled away from the mountain-top to mine…. “Ach so, Herr Major!”… for a long moment, the war had ceased to exist….

The poem was in fact To Thaliarchus, a passage beginning (in Paddy’s schoolboy translation) “See Soracte’s mighty peak stands deep in virgin snow….” Lane notes that this incident feels like “the last, companionable gasp of a civilization” that bound Europe together for over a thousand years. More than that, it’s an ability we may have lost forever. Who needs memory, with Google always at our fingertips?

Women were particularly susceptible to Paddy’s charm, and Cooper, his biographer, interviewed by Allison Pearson for the Daily Telegraph, told her “‘He would never talk about the women in his life.’ Eventually, [Cooper] deduced that whenever he said of a woman, ‘we were terrific pals,’ he had been to bed with her.”

Some women were much more than pals. Joan Rayner, neé Monsell, whom Paddy met in wartime Cairo and stayed with, but not exclusively, for the next six decades, was to be his companion during the research and writing of his every book, supporting him through much of his writing life, and building a home with him in the wilds of the Mani. They finally married, it seemed almost impulsively, in 1968, and were together until her death in 2003.

Like Joan many of his women friends were bluebloods, which gave ammunition to those who were immune to his charm. Ian Fleming’s wife Ann arranged an invitation for Paddy and her to spend a weekend at the house of W. Somerset Maugham, a writer Paddy admired but had never met. His attempts at humor were disastrous – for once, his prodigious capacity for alcohol failed him – and Maugham asked them to leave. Maugham later called him “that middle-class gigolo for upper-class women.”

This and many hard-to-imagine adventures are to be found in Cooper’s biography, including the rest of Paddy’s walk across Europe – and, not least, the truth about the German destruction of Anogeia and the villages of Crete.

More next time. For those who can’t wait, an introduction to all things Paddy starts here.

November 12, 2013

Patrick Leigh Fermor: A Time of Confusion

Billy Moss and Paddy Leigh Fermor in German uniform, prior to kidnapping General Kreipe. From ‘Ill Met by Moonlight’

On first reading John Fowles’s The Magus, a novel set in the fifties, an odd locution snagged my attention. Early in the story Nicholas Urfe is talking to a man who previously held the teaching post in Greece that Urfe is about to take up. “He had been parachuted into Greece during the German occupation, and he was very glib with his Xans and his Paddys and the Christian names of all the other well-known condottieri of the time.”

Xans and Paddys? Later I found out that Xan was Alexander Fielding and Paddy was Patrick Leigh Fermor, colleagues in Crete during World War II. While the hapless Urfe’s disdain for these condottiere is partly explained by the fact that the character’s unloved father is Brigadier “Blazer” Urfe, it may also reflect the author’s own feelings. If so, Fowles was in the minority, but he was not alone.

It wasn’t until 1984 that I learned more about Leigh Fermor, while trying to walk from one end of Crete to the other following ancient paths described in John Pendlebury’s The Archaeology of Crete (1939). The island is 160 miles long, studded with mountains of knife-edged weathered limestone; I ended up mostly taking the bus. But at the cost of shredding a pair of leather boots, I did manage to walk good chunks of it.

One leg started in the village of Anogeia, on the northern slope of Psiloritis, where the bus dropped me at midday. It was a place of no charm, a collection of blocky concrete houses.

The Anogeians, like Greeks everywhere, peppered the newcomer with questions; at the mention of “American,” however, they all clammed up. Later that day I walked to the nearby ruin of Axos. From my journal: “on the way back a guy gives me a lift in his truck and accuses me of being a spy…. ‘Crete is nice,’ I offer, and his reply is ‘Nice for Americans.’”

That trek took me from Anogeia over Psiloritis and across the Messara Plain as far as Kommos on the Libyan Sea. A week later I was back at home base in Koutoulofari, where Grecophile Rosemary Barron had a cooking school. I asked her about Anogeia. For one thing, she said, it had long been an outpost of the KKE, the Greek Communist Party, much in the minority in Crete.

As to the tedious architecture, it was postwar. “The Germans leveled Anogeia during the war.” She named several books in English that could tell me more: The Villa Ariadne by Dilys Powell, Ill Met By Moonlight by W. Stanley Moss, and the refreshingly non-Anglocentric The Cretan Runner, by George Psychoundakis – translated, and with an introduction, by Patrick Leigh Fermor.

From these, I learned that the archaeologist Pendlebury, whose tracks I’d been following, had organized British support for the Cretan resistance but was killed within days of the German invasion in 1941. That Xan, Paddy, Billy Moss, and other members of the SOE had carried on through the war under extraordinary hardships.

And I learned what made Leigh Fermor famous, alluded to only in passing in his introduction to Psychoundakis’s book but spelled out in the others: he led the successful kidnapping of the German General Heinrich Kreipe, then commandant of Crete, who was quartered in Arthur Evans’s former home, the Villa Ariadne in Knossos. The first stop after they hijacked Kreipe’s car, on the way to evacuating him by boat, was Anogeia.

With this much to go on, I assumed what many others had assumed, based on the Germans’ own pronouncements – that Kreipe’s abductors were at fault for the death and destruction visited upon Anogeia and other villages where the Germans suspected he’d been held.

As late as the late nineties I still thought that was the true story. My 1997 novel Secret Passages is set in Crete, the protagonist a physicist named Minakis. Telling the story of his youth, he says, “As for the war, you may have heard stirring tales of kidnapped German generals and the like. These were English adventures, worse than useless to the Greeks.” Minakis has earned his opinion, but it is one not shared by most Cretans.

A few years ago, I discovered what Leigh Fermor did with his life before and after the war, when I stumbled upon his 1977 memoir, A Time of Gifts, the first of three volumes recounting his walk across Europe from Holland to Constantinople beginning in 1934. It was an extraordinary work, and I read more. A Time to Keep Silence (1957) tells of his sojourns in monastic communities. I devoured Mani (1958), Roumeli (1966), and part two of his hike to Constantinople, Between the Woods and the Water (1986). A startlingly different take on Leigh Fermor came from In Tearing Haste (2008), his long correspondence with Deborah Devonshire.

Last week I finished Patrick Leigh Fermor, An Adventure, by Artemis Cooper, which puts his remarkable life in perspective. Kidnapping a German general led to fame, but that was almost the least of it. More next time.

October 24, 2013

Wormholes vs. Wormholes

Did I mention that wormholes are prime examples of why science fiction writers, along with all other fiction writers, have to lie to tell a good story? A day after posting that claim, I caught an article on the National Association of Science Writers website by Dennis Meredith, introducing his novel Wormholes. His first words were, “I’m a liar and a thief, and I think that’s okay.”

Did I mention that wormholes are prime examples of why science fiction writers, along with all other fiction writers, have to lie to tell a good story? A day after posting that claim, I caught an article on the National Association of Science Writers website by Dennis Meredith, introducing his novel Wormholes. His first words were, “I’m a liar and a thief, and I think that’s okay.”

So I just had to read the book. Wormholes turns out to be a ripping good yarn that moves swiftly from one disaster to another. The solar system, Earth in particular, is under siege by what an obsessed and slightly wacky theoretical physicist named Gerald Meier decides are “wormholes.”

Each onslaught has a dramatically different effect. Putative wormholes boil the ocean, or open on vacuum, or on Earthlike planets, methane oceans, or antimatter universes. The holes share one thing in common – and this is where I got lost, though not for long. As theorist Meier tells us, “I knew these might be space-time holes, but they couldn’t be black holes.”

Hmm. The essence of a black hole is that it’s a singularity, a gravitational collapse. “Classical” (Schwarzchild) wormholes form when singularities in two universes, or two regions of the same universe, join and very temporarily form a bridge – in essence they’re double black holes. (See Misner, Thorne, and Wheeler’s venerable text, Gravitation.) They are surrounded by event horizons, within which nothing can escape, and vary in mass: the more massive, the bigger the event horizons.

The wormholes in Wormholes aren’t like that. Apparently they’re not gravitational phenomena, and they’re all pretty much the same size – small, say weather-balloon size. While temporary, they stay open for a long time, and their edges (surfaces?) are sharp. Perhaps most unusual, they are exquisitely sensitive to magnetic fields, including fields as weak as Earth’s.

“That’s when I became a liar,” Dennis Meredith explained, in the article that first inspired me to seek out his novel. “To spin an exciting adventure, I invented physics.” He well understands that his fictional wormholes are only distantly related to the wormholes of astrophysical theory. “I became a thief when I misappropriated the popular term ‘wormholes’ to name these objects.”

It’s an interesting disconnect for the reader, to expect one kind of wormhole and discover that’s not what you’re dealing with – a little like the moment in Disney’s 1954 movie 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, one of my all-time favorites, when you find that the Nautilus isn’t battery-powered, as you might have expected from Verne’s novel (1870), but nuclear-powered, like the U.S. Navy submarine launched the same year.

For all the story’s implausibilities, novel wormholes don’t hurt it a bit – it’s still a thrilling ride, crisply told. Physicist Gerald Meier and plucky geologist Dacey Livingstone are well realized, as are the other main characters, the scientists especially; science-writer Meredith knows the tribe’s passions, insecurities, arrogances, occasional evasions, quirks, and dirty tricks, all its strengths and foibles. As a fiction writer, he does like his modifiers, but there are felicities even in the verbal rococo, such as a man “indolently wallowing” on a chaise longue while his wife pleads with him to mow the lawn. (He’ll soon pay for that mellifluous lethargy.)

Meredith describes countries and cultures and landscapes deftly; his plot twists are not only startling but often underpinned by solid research. One vivid and excruciating scene involves the last minutes of a supertanker caught when the ocean beneath it begins to boil. The author knows (or has studied) supertankers well enough to make you believe it.

It’s not the world or the universe we live in or surmise might exist, but it’s a possible world in the sense that most fiction is both possible and true: it takes place in a world “where the fiction is told, but as known fact rather than fiction.”

October 11, 2013

Big Blunders: When the Multiverse is Not the Answer

Astrophysicist Mario Livio has a gift for clear prose and something more: the ability to turn up – or track down – the odd fact, the misunderstanding, the story behind the story everybody thinks they know, the stuff that makes science come alive.

Astrophysicist Mario Livio has a gift for clear prose and something more: the ability to turn up – or track down – the odd fact, the misunderstanding, the story behind the story everybody thinks they know, the stuff that makes science come alive.

The discussion of infamous scientific goofs in Livio’s recent book, Brilliant Blunders, covers familiar ground. They include Charles Darwin’s misguided attempt, long before Mendelian genetics became known, to rescue natural selection from the persuasive “paintpot” theory of inheritance that indicated variations would soon be swamped. Darwin proposed something called pangenesis, unpersuasive even to himself.

William Thomson, Lord Kelvin, attacked Darwin by demonstrating that Earth was cooling so fast it could not have been around long enough for species to evolve; he persisted in this opinion even after the discovery of radioactivity, source of half the planet’s heat.

Linus Pauling takes his lumps for beating Watson and Crick into print with an inside-out, triple-helix model of DNA, incorporating a fundamental error of chemistry.

Fred Hoyle’s mistake was not his steady-state theory, perfectly reasonable at the time. (Livio shows that when Hoyle uttered “big bang” in a BBC interview it wasn’t derogatory, just plain speaking.) Like Kelvin, however, Hoyle refused to relent in the face of overwhelming evidence, including discovery of the cosmic microwave background, the nail in the steady state’s coffin.

What Livio concludes from these examples isn’t original – “blunders are not only inevitable but also an essential part of progress in science” – but his storytelling is both fresh and fascinating.

His final example is the “biggest blunder” we’ve heard most about in recent years. It’s what Albert Einstein, after Edwin Hubble discovered that the universe is in fact expanding, supposedly said about the cosmological constant he’d introduced into General Relativity to keep the universe stable.

“Did Einstein actually say this?” Livio asks. His original research shows the answer is probably no. The words were first recounted after Einstein’s death in reminiscences by George Gamow, in this case a very unreliable narrator.

Einstein certainly wasn’t happy with his cosmological constant, but Livio notes with some irony that his “true blunder was to remove the cosmological constant.”

In late 1997 the Supernova Cosmology Project and the High-Z Supernova Search Team independently discovered that universal expansion is accelerating. The cause would soon be called dark energy. So far, measures of expansion from supernovas and baryon oscillation are entirely consistent with dark energy being the cosmological constant.

If the cosmological constant is real, however, its physical nature – the force with which it expands space and pushes mass apart – is unknown. It’s apparently some form of the energy of the vacuum, but no good theory exists to explain its tiny but significant value.

Enter the multiverse. “Consider a universe harboring the same laws of nature as ours,” Livio suggests, “and the same values of all the ‘constants of nature’ but one.” You get the picture. In a multitude of different universes, we just happen to live in one where the cosmological constant has precisely the value needed to produce the accelerating expansion we observe.

Many scientists find this anthropic reasoning loathsome – so do I – if only because it puts so many interesting questions forever beyond hope of an answer. Yet Livio defends it. His argument has a spectacular flaw – his own contribution to his list of blunders.

Just because other universes can’t be observed doesn’t mean they aren’t real, Livio says, then adds the obligatory caveat: they have to be “predicted by a theory that gains credibility in other ways…. If a theory makes testable and falsifiable predictions in the observable parts of the universe, we should be prepared to accept its predictions [elsewhere].”

Theories that predict or at least allow a multiverse are far from proven anywhere, but that’s not the crux of the problem. Whether the value of the cosmological constant is set arbitrarily small or arbitrarily large, there’s no persuasive physical explanation. Why does it have any value?

Until there’s a testable theory of why a cosmological constant can have a range of values, the multiverse is no explanation for dark energy. It’s not enough to say that’s just the way it is.

October 4, 2013

Fictional Worlds: True, but Possible?

In an essay titled “Truth in Fiction,” philosopher David Lewis argued that worlds created by fiction writers, worlds where “the fiction is told, but as known fact rather than fiction,” are not only possible but real.

In an essay titled “Truth in Fiction,” philosopher David Lewis argued that worlds created by fiction writers, worlds where “the fiction is told, but as known fact rather than fiction,” are not only possible but real.

“When I profess realism about possible worlds, I mean to be taken literally,” Lewis wrote elsewhere about his possible-worlds theory, which he called modal realism.

It’s an intriguing proposition for those of us who sometimes wake as if from a trance after spending time with imaginary characters who have sprung into being as we scribbled away or whacked at a keyboard. We thought we were just making it up.

Lewis uses Sherlock Holmes stories as a benchmark, set in a realistic world much like our own. Of other kinds of fiction, which may retail the exploits of superheroes from other planets or hobbits, he says huffily, “what a mistake it would be to class the Holmes stories with these!”

Nevertheless, a fiction is impossible if and only if “there is no world where it is told as known fact.” That leaves a lot of room. If in the first volume of a novel set in 1878 our hero has lunch in Glasgow and in the last volume shows up in London later the same day, he either used a then-unknown form of transit or, what may seem more likely, his author was careless.

In the latter case one could suppose a “minimally revised version” of the novel that makes the hero’s movements feasible, Lewis suggests, assuming “there were ways to set the times right without major changes in the plot.”

But here’s the kicker. “There might not be, and in that case perhaps truth in the original version – surprising though some of it may be – is the best we can do.”

Lewis joined the faculty of Princeton University in 1970, where thirteen years earlier Hugh Everett III had proposed the theory later known as the many worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics.

Quantum states are superpositions of possible alternatives – for example, a particle with both spin up and spin down, or, more notoriously, Schrödinger’s cat both alive and dead – which are only resolved when an observer makes a measurement, thus “collapsing” the wave function.

Everett’s solution to this non-common-sensical conundrum was to posit a universal wave function with an uncountable infinity of possible branches describing the whole of existence, in which all possible worlds are real. The collapse of local wave functions is illusory – all alternatives continue.

Scorned at first, not least by Neils Bohr, many worlds theory is taken seriously and remains the object of lively debate. For obvious reasons it’s a favorite of science fiction writers, first coming to wide public attention in a 1976 article in Analog.

Was David Lewis’s possible worlds theory influenced by Hugh Everett’s many worlds theory? It’s suggestive that Lewis followed Everett at Princeton, but nothing more than that. I’m pretty sure Everett’s presence at Sandia Base in 1956, when I was a teenager there (I don’t recall meeting him), had no influence on my 1981 novel Re-entry, which explicitly invokes many worlds. More likely it was Analog.

What the two theories don’t have in common is necessary physics. Everett’s many worlds exist in a universe with physical laws the same everywhere. Lewis’s possible worlds require only “known fact,” which may involve quite different physics.

To change one’s physics, one needs multiple universes. Brilliant Blunders, Mario Livio’s recent book about scientists’ mistakes, describes how multiple universes have been invoked to explain otherwise unanswered questions about dark energy.

Are even multiverses enough to encompass all possible worlds? More next time.

September 26, 2013

Fiction, Science, Truth

Lorentzian wormhole, by Allen McC., Wikimedia Commons

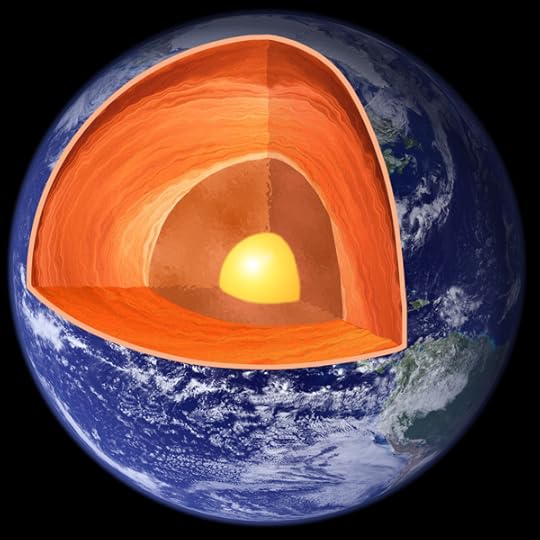

In my last post I mentioned the apparent absurdity of a story that depends on drilling through Earth’s mantle with a rig that makes hole – when it’s actually working – at sixty miles an hour.

Reality check: the Kola Superdeep Borehole, the deepest hole yet, began drilling in 1970 and stopped nineteen years later after running into insurmountable difficulties, namely heat. It had reached over seven and a half miles beneath the surface but had not penetrated Earth’s crust.

One could tell many gripping stories (and many of them factual) about such an effort, but none would be titled Core. A human-scale story about drilling a hole to the center of the Earth, like most hard science fiction, requires cheating.

I broached this theme in an essay for the New York Review of Science Fiction in 1994, titled “Loopholes in the Net,” a title inspired by Gregory Benford’s paraphrase of Robert Frost’s remark about free verse: “I’d rather play tennis with the net down.” Benford proposed that “Hard sf plays with the net of scientific fact up and strung as tight as the story allows.”

As the story allows? Most hard sf authors care enough about scientific accuracy to know when they’re bending the rules, but in fact almost no science fiction story can tolerate simultaneous adherence to real-world experience and well-founded theory.

A common victim is time. Space adventures routinely ignore relativity, and even novels that respect and depend on relativistic effects, such as Joe Haldeman’s notable Forever War, have to cheat. Wormhole gateways to distant parts of the universe (Haldeman’s “collapsars”) are a favorite device, but a ship falling into a wormhole would approach infinite velocity, at which point time stops.

Instead of boasting about playing with the net up, science fiction writers of all degrees of hardness could admit what they have in common with the entire fiction-writing community: all fiction is a lie, and also true.

This isn’t the claim, well stated by Ralph Waldo Emerson, that “Fiction reveals truth that reality obscures,” unfortunately since devolved to a cliché and an excuse for lazy research. More fundamentally, the question of truth in fiction gives rise to a paradox not unrelated to the liar’s paradox beloved of logicians (“All Cretans are liars,” said Epimenides the Cretan), which lies deeper and has inspired a literary offshoot of the wonderfully named possible worlds theory.

A much-read 1976 essay by the late Princeton philosopher David Lewis, succinctly titled “Truth in Fiction,” describes the dilemma and roughs out a solution: “We can truly say that Sherlock Holmes lived in Baker Street, and that he liked to show off his mental powers,” he begins. Since that truth is a different sort of beast than truth in our real world, he suggests, “Let us not take our descriptions of fictional characters at face value, but instead let us regard them as abbreviations for longer sentences beginning with an operator ‘In such-and-such fiction…’.”

The point, expressed in philosopherese, is that such an operator “may be analyzed as a restricted universal quantifier over possible worlds…. The worlds we should consider, I suggest, are the worlds where the fiction is told, but as known fact rather than fiction. The act of storytelling occurs, just as it does here at our world; but there it is what here it falsely purports to be: truth-telling.”

Lewis meant those words, and those worlds, literally. Not least among the pleasures of his essay are encounters with weird-sounding concepts like Meinong’s jungle and philosophical zombies. What interests me more, however, is the clear parallel with the many worlds theory of quantum mechanics. More on that next time.

September 19, 2013

Core and The Core: Why Not Brazzletonite?

In 1947, while teaching a graduate course in physics at the University of Chicago, Enrico Fermi famously posed the question, “What is the deepest hole that may be dug into the Earth?” Since it was an experiment that had never been done, he didn’t have the answer, but it sure got the students thinking.

In 1947, while teaching a graduate course in physics at the University of Chicago, Enrico Fermi famously posed the question, “What is the deepest hole that may be dug into the Earth?” Since it was an experiment that had never been done, he didn’t have the answer, but it sure got the students thinking.

The first thing you’d need is a material that can penetrate the very hard, very high-pressure, very hot deepest mantle. In the movie The Core, an ingenious inventor, Edward Brazzleton (played by Delroy Lindo), comes up with superhard, refractory “unobtainium,” based on boron nitride, to sheath a drill ship that can propel itself through Earth’s mantle, while not baking the people inside it to a crisp.

Personally I think the script writers missed a great opportunity by not naming unobtainium, which obviously was obtainable, brazzletonite instead.

“Everybody knows that boron nitride crystals are six times harder than diamond,” Brazzleton says. Well… boron nitride is certainly an interesting compound, and at least one crystalline arrangement is a little harder than ordinary diamond, but some rare forms of diamond are harder still.

Boron nitride is indeed refractory – it’s used to line crucibles in steel mills; diamonds, on the other hand, catch fire at 800 degrees Celsius, roughly 1,500 degrees Fahrenheit. Brazzleton boasts that unobtainium can withstand 9,000 F. Unfortunately, the temperature of the liquid iron core rises from 8,000 to 11,000 F. As insulation, unobtainium would fail.

In Core the novel, the composition of hudderite, invented by Cyrus Hudder, is hinted at – “ice-seven lattices, diamondlike lattices, beryllium fluoride interprenetrating silicon oxide” – but never specified. No such material will ever be created, even in theory.

Brazzleton does have the right idea about launching his ship from dry land, however. Unfortunately he’s overruled by geophysicist Conrad Zimsky (Stanley Tucci).

Zimsky: We need to cut our actual digging time as much as possible…. We’re digging a hole, why not start with a hole? Marianas Trench in the Pacific. Six miles below sea level….

Once under way, the drill ship will reach a vertical speed of sixty miles per hour. Says Zimsky, “We’ll be through the crust in fifteen minutes and into the mantle. Twenty-four hours to the core….”

The ocean launch in The Core takes place during a hurricane and involves a dive of over six miles. So how much time did they save by carrying their whole project across the Pacific?

The oceanic crust averages about six miles thick. The continental crust averages about twenty miles thick. Had the ship been launched from the comfort and stability of Brazzleton’s solid-ground desert site, the additional fourteen miles through the softest layer of the planet would have cost just a quarter of an hour. The crust is nothing; the 1,800 mile journey through the mantle is the real challenge.

In Core, the novel, the drill site was in West Texas. But coincidentally (no doubt), there is also a deep ocean dive in the novel. Before joining the CORE drilling project Queenie Toubou, a Tongan, was an oceanographer and made a dive to the bottom of the Tonga Trench. Luckily she was not aboard the submersible on a later mission when it imploded, but the experience led her to become expert at engineering structures capable of withstanding extreme pressure. She and Brazzleton would have had lots to talk about.

There are many other odd coincidences between Core the book and The Core the movie. One that’s not odd is that they both stretch scientific likelihood to the breaking point and beyond. A ship (movie) or a drill rig (novel) that can drill straight down at sixty miles an hour? Come on….

My novel tries to distract from its cheats with sleight of hand. The movie trumpets its absurdities, apparently because it doesn’t realize how absurd they are.

The most discouraging thing about watching The Core in the theater was not the mangled science — that disaster was evident right from the opening scene that featured fried pacemakers — but the waste of a superb cast, including Lindo, Tucci, Aaron Eckhart, Hilary Swank, and others. What could they have done with a script whose base was, perhaps, a little less loose?

September 12, 2013

Core and The Core: Loosey Goosey

The last time I looked, the Wikipedia stub “Core (novel)” notes that my novel Core was published in 1993 and says, “A 2003 film, The Core, was loosely based on this novel.”

Pretty loose, all right, since I never heard of the movie until I saw the poster in a multiplex. But that’s a relief: in a 2009 “poll of hundreds of scientists about bad sci-fi films,” in a National Academy of Sciences initiative led by actor and former chemist Dustin Hoffman (Wikipedia again), “The Core was voted the worst.”

It would be nice to shake the association, although that’s not easy. Titles can’t be copyrighted, and neither can ideas. In the case of a novel, what can be copyrighted are the words, and The Core doesn’t use Core’s words. There are, however, an unusual number of coincidences.

In both novel and movie, the plot is set in motion by the unusually rapid collapse of the Earth’s magnetic field, an event that usually takes thousands of years, occurs infrequently, and is often followed by a reversal of the magnetic poles. In both novel and movie, scientists address this monumental inconvenience by drilling a hole to Earth’s liquid outer core — in Core they use drilling tools, in The Core they ride down in a ship.

In both novel and movie, a new kind of hard, refractory material is essential to the effort — Core calls it hudderite after its inventor, The Core calls it “unobtainium,” which made some people think the movie was an intentional comedy. (Probable inspiration: the temporary names given newly discovered elements, element 117 being ununseptium, 118 ununoctium, and so on.)

And in both novel and movie, the collapsed magnetic field is restored by setting off nuclear bombs in the liquid iron core — in Core to trigger vortices and restart the geodynamo, in The Core to re-spin the solid nickel-iron inner core (a puzzling approach, since the inner core’s very slow spin does not contribute to the magnetic field).

As far as I know, the quick collapse of Earth’s magnetic field had never been used in fiction before I wrote Core. Reversals of the field’s polarity were, however, a lively subject in geology. Rob Coe, Michel Prévot, and Pierre Camps had been studying magnetic orientations frozen into the thin layers of iron-rich basalt that make up Steens Mountain in Southeastern Oregon (an area I know well) and, two years after the novel appeared, they published in Nature “New evidence for extraordinarily rapid change of the geomagnetic field during a reversal.”

Earth’s magnetic field deflects many charged particles from the solar wind and cosmic rays, which would otherwise not only expose the planet to more particle radiation (although most shielding is from the atmosphere) but impact the ozone layer and expose the surface to more ultraviolet radiation as well, particularly at high altitudes.

What would happen if the field suddenly collapsed? Here’s where the coincidences between Core and The Core take divergent paths.

In the novel the chief threats are burns, radiation sickness, and eventually cancer, particularly at high altitudes, and occasional solar flares that wreak havoc on communications. One minor incident involves an iron shed and a flock of confused pigeons, which depend to some extent on the magnetic field for navigation; elsewhere, and offstage, some Boy Scouts get lost.

What would not be the consequences? Failed pacemakers, lightning storms, mass bird suicides, or planes falling from the sky. At one point in the movie, geophysicists Josh Keyes (Aaron Eckhart) and Conrad Zimsky (Stanley Tucci) list some of the dangers they expect:

Keyes: So now you get all this high weirdness. We’ve got electromagnetic pulses that fry pacemakers, overload bird navigational senses…. As the EM field becomes more and more unstable, we’ll start seeing isolated incidents – one plane will fall from the sky, then two, then, in a few months, anything, everything electronic will be fried.

Zimsky: Static discharges in the atmosphere will create superstorms with hundreds of lightning strikes per square mile…. The Earth’s EM field shields us from solar radiation. When that shield collapses, microwave radiation will scour the planet.

Last I heard, airplanes aren’t held aloft by magnetism, and lightning strikes are electrical (not magnetic) discharges. The chief dangers to pacemakers are strong magnetic fields, so one might ask how the absence of Earth’s relatively weak field could “fry” pacemakers. Not to mention that the sun’s microwave radiation (as opposed to energetic ultraviolet radiation) wouldn’t bother a fly.

But wait! Keyes and Zimsky aren’t talking about the magnetic field after all. They’re talking about something they call the EM (electromagnetic) field. Whatever that is, it’s not the geomagnetic field whose collapse we’ve carelessly assumed is causing their problems.

Whatever it is that actually collapses in The Core, it takes a heroic journey to fix it. More on that in the next post.

Paul Preuss's Blog

- Paul Preuss's profile

- 21 followers